The Bank of International Settlements is taking a more public stand on a matter it took up with central bankers privately prior to the crisis, namely, that overly low interest rates stoke asset bubbles. Its chief economist William White had been warning against overly lax monetary policy as early as 2003:

White recognized the brewing disaster. The analysis department at the BIS has a collection of data from every bank around the globe, considered the most impressive in the world. It enabled the economists working in this nerve center of high finance to look on, practically in real time, as a poisonous concoction began to brew in the international financial system.

White and his team of experts observed the real estate bubble developing in the United States. They criticized the increasingly impenetrable securitization business, vehemently pointed out the perils of risky loans and provided evidence of the lack of credibility of the rating agencies. In their view, the reason for the lack of restraint in the financial markets was that there was simply too much cheap money available on the market. To give all this money somewhere to go, investment bankers invented new financial products that were increasingly sophisticated, imaginative — and hazardous….

“One hopes that it will not require a disorderly unwinding of current excesses to prove convincingly that we have indeed been on a dangerous path,” White wrote in 2006.

White has retired, but his successors are taking up his theme more publicly than he was able to. One of a series of papers released today notes:

Easy monetary conditions are a classic ingredient of financial crises: low interest rates may contribute to an excessive expansion of credit, and hence to boom-bust type business fluctuations. In addition, some recent papers find a significant link between low interest rates and banks’ risk-taking, pointing to a different dimension of the monetary transmission mechanism, the so-called risk-taking channel (Borio and Zhu (2008), Adrian and Shin (2009)). This channel may operate in at least two ways. First, low returns on investments, such as government (risk-free) securities, may increase incentives for banks, asset managers and insurance companies to take on more risk for contractual or institutional reasons (for example, to meet a target nominal return). Second, low interest rates affect valuations, incomes and cash flows, which in turn can modify how banks measure risk.

This reports marshals empirical evidence (well, White and Claudio Borio had as well, and it was ignored). It makes an argument similar to that of John Taylor, that rates were held too low for too long (17 quarters in the US, 10 quarters on average for the EU). The study found that keeping rates overly lax for 10 quarters led to increase in their odds of defaulting of 3.3%. It also found that every 1% inflation-adjusted increase in housing prices for six consecutive years in excess of the long term average increased the odds of bank default by 1.5%.

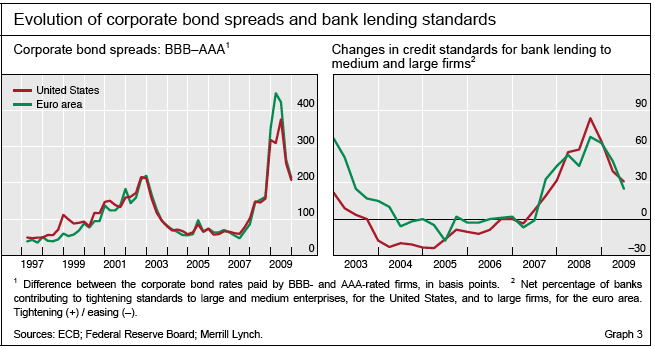

The study also looked at credit spreads and lending officer attitudes:

Note that this study, along with the larger quarterly report of which it is a part, did not argue that current monetary policies are too lax.

“It was probably the biggest failure of the world’s central bankers since the founding of the BIS in 1930. They knew everything and did nothing. Their gigantic machinery of analysis kept spitting out new scenarios of doom, but they might as well have been transmitted directly into space.

For years, the regulators of the global money supply ignored the advice of their top experts, probably because it would require them to do something unheard of, namely embark on a fundamental change in direction.

The prevailing model was banal: no inflation, no problem.”

This is an indictment of Greenspan. Once the public understood inflation during the 1970s, inflation became politically incorrect. Because looting the public has to be done stealthily inflation had to be avoided. The looting, however, could be accomplished by any other means and did; by dismantling laws and regulations and creating opaque financial instruments.

Greenspan is responsible for letting the crooked bankers run their scams. Paulson’s accomplishment was acquiring immunity from the law (how is that possible?) that in turn conferred immunity on every institution his BAILOUT touched. Therefore, no arrests, no trials, no blame, and now, with a new administration, just more of the same.

Ok, so inflation stays low because the crap that gets measured is made for next to nothing given excess industrial capacity (Brenner and Gower etc.) and excess labor round the world (and the stuff that doesn’t get measured – like oil – doesn’t count); that let’s Greenspan keep interest rates low without prices rising (still no inflation); so that leads to asset inflation – since there’s no place else to put capital but in those assets, since there’s already excess capacity – no real economy profitable opportunities.

But inquiring minds want to know: Does Greenspan not look White in the eye because White has caught Greenspan’s game (the bubble blowing is intentional, it’s the only way to save capitalism with excess capacity and global imbalances); or because Greenspan had no idea of the implications of his policy before White expressed them, but understands White is right, and is ashamed?

I guess that matters relative to one’s conspiratorial dispositions – but we have at least three alternative accounts for the people choosing to keep interest rates low: 1) They are incompetent; 2) they are outright thieves; 3) they are doing what they think will sustain capitalist economies, and aren’t much disposed to abandon core beliefs especially, especially about the perpetual viability of capitalism just so long as they manage it correctly…

Now for many readers, (1) and (3) are not entirely separate classes – if only they’d had a better theory…

But I mean to suggest that is it possible the best minds with the best theory couldn’t have done differently. If blowing bubbles is the only way to keep capital in motion sans real economy opportunities for profit, well?

And so you keep interest rates high, eventually raise unemployment, and then have to adopt employer of last resort policies?

Or Gold….

Or as dueling theories will go …

The BIS has been a voice of reason the past few years, IMO. And I say that without having kept up enough with them to really, well, say that. But in any event that’s my impression from what I HAVE read.

Dave:

Incompetence should be assumed, thievery is an unlikely motive I would say except at the margins – the best route for the greedy and the powerful is in fact #3 – and as regards this last point, 3, the sustainability of the capitalist economies…

Yes and no, I’d say. I don’t see the problem as whether or not a hypothetical capitalist economy is sustainable. Perhaps one day we’ll be able to test that, but at the moment it’s moot. What we have are a number of market-driven economies controlled in different fashions but with the same purpose: to make them less turbulent and to slow the pace of cannibalism endemic to free markets. Or if you wish to view things more cynically, then controlled in order to preserve the existing hierarchy of power and wealth (or to establish a new one and then preserve that). And part of this involves, at least in the modern era, using interest rates to float the previous paradigm long past the point where it would normally implode.

I wouldn’t agree that the problem is non-existent opportunity for profit – there has never been a time when people ran out of ideas – but rather an economy which has become increasingly structured for a world that simply does not exist. So that it is no longer individuals that decide job and profit opportunity but the politicians and bankers that maintain (or break) that structure. We have a bloated finance sector, not because it is needed, but because it is encouraged. The more irrelevant it becomes, the more it must be encouraged, and the more our economic decisions become based, not on wants and satisfactions of people, but on the caprices of the government/banking complex. We play the game, we gamble, and we’re all aware of it.

It’s not a conspiracy at all. At any given point, the system merely does what it must to sustain itself, as all “good” (enduring) systems do, regardless of individual motive. Principles may be starting points but pragmatism is the road traveled. I don’t mean to be fatalistic. But real change is an “outlier” event, the result of a glitch in the matrix (if you will) or of an external force, and consequently, even though we might vote for it, we probably will not get change except through some calamity.

IMO this is a feature of all hard-wired social structures (meaning any with laws). And all organisms, and all chemical reactions and all chains of causality. I don’t know that society needs to be such, but perhaps it does. In any event this is all conjecture and I think we’re past the point where general theory can play much role. Respect to the BIS, but voices of reason they may be, they are Cassandras. I think the name of the game today, and for the immediate future, is shuffle assets, think quick and SURVIVE. And do good by helping others to do the same.

2010, the year of previously unheard amounts of CB created liquidity sloshing around the globe chasing currency yields. The term “hot money” will be replaced with the term “nuclear money”

Slowly but surely the illusions of the modern shatter and the insight of the Austrian that capitalism leads naturally to steady deflation emerges.

So, in other words, Hayek was right in that easy money raises future expectations which causes over-leveraging and then a crash.

That interest rates had to be kept low the early 2000s – the years of the invasion of Iraq – the years of the invasion of Afghanistan -the years of the largest military budgets in history.

Of course, wars have nothing to do with inflation, it’s all in consumer interest rates payable & greedy unionized workers, right? Well….

http://ar.to/2009/08/inflation-and-the-fall-of-the-roman-empire

Plus ca change?

Bingo, all this talk about consumers and citizens is bunkum. The Empire must expand no matter what guise it chooses to ware in-order to sustain its self.

Costard with all respect, GB II and Co were so malignant it buggers the mind *IT WAS THIEVERY* with fore thought and not synergy, aided and abetted by a belief system which granted them impunity in their actions. In which they promoted as righteous and pure of spirit in the name of compassion to the fearful and weak of this world, injecting it straight into the mailable American mind, the after affect of which we globally, will feel for generations.

And may I add has cracked the door open to a host of whack jobs that may on election day re-assert their beliefs upon us all. Call them all the names you like, it has never stopped their ilk in the past and in fact emboldens them to further heights of lunacy (btw the masses eat this up as people of action/quick solutions to their suffering).

Decorum is for dinner party’s not street fights, make no illusions about it, power will not resend voluntarily, it must be wrest from those that have become accustomed to it. Especialy when gifted from above!

Yves,

I just read BIS’s paper (“Monetary policy and the risk-taking channel”) in the post. Its conclusion is, as you notice, very simple: low interest rates over an extended period cause an increase in banks’ risk-taking.

My concern on BIS’s paper is “What about Japan?” It drew the conclusion by examining banks only in Europe and the United States. Japan’s interest rates have hovered around zero for more than 10 years, but I don’t see any serious risk-taking by Japanese banks. They backed away from risky opportunities to more stable business in the low interest rates condition.

I think (and of course, this is not confirmed by any solid academic methods) that regulatory environment would have additional impetus to banks’ risk-taking activity.

Low capital gains taxes and excessively high tax exemption on home sales up to $250k for individuals and $500k for families lead to excessive risk taking.