By Richard Alford, a former economist at the New York Fed. Since then, he has worked in the financial industry as a trading floor economist and strategist on both the sell side and the buy side.

A week ago, in Atlanta, Bernanke responded to his critics, including John Taylor of Taylor Rule fame (the Taylor Rule is a benchmark widely used by central banks in setting their “policy” interest rates). Bernanke asserted that monetary/interest policy has been appropriate-and was not” too low for too long” from 2001-2006. Taylor responded in a WSJ Op-Ed piece on January 11th reasserting his position that interest rates were “too low for too long”. A very public debate has been joined. Taylor’s view is based on his chosen variant of the Taylor Rule, while Bernanke cites his own chosen variant of the Taylor rule.

This post establishes that interest rates were “too low for too long” (from 1996-2006) while dispensing with the Taylor Rule and its sensitivity to choices of inputs and assumptions. It does so in a framework that employs definitions and measures favored by Bernanke. The frame work of the analysis is then used to answer other questions about economic policy in the past and going forward.

The Deflationary Threat?

Price stability/inflation targeting has been center stage of interest rate policy since Japan began its lost decades. Fear of deflation dominated the thinking of the Fed. This was especially evident in the response to the recession of 2001. The decidedly expansionary monetary policy adopted at the time was justified in terms of preventing a deflationary episode like Japan’s. In a February 2002 speech titled “Deflation: Making Sure ‘It’ Doesn’t Happen Here.” Bernanke defined deflation as:

“Deflation is a general decline in prices, with emphasis on the word “general”.

Bernanke was drawing a distinction between changes in relative prices of some goods on the one hand and deflation – pervasive declines in prices – on the other. Later in the speech, Bernanke re-emphasized the point: “Deflation per se occurs only when price declines are so widespread that broad-based indexes of prices register ongoing declines.” However, Bernanke and the Fed allow for exceptions. For example, food and energy inflation/deflation have been ignored even when changes in food and energy prices registered on broad-based indexes.

In the speech, Bernanke also specified the cause of deflation: “Deflation is in almost all cases a side effect of a collapse of aggregate demand –a drop in spending so severe that producers must cut prices…to find buyers.” In a footnote, Bernanke added:” I don’t know of any unambiguous example of a supply-side deflation, although China in recent years is a possible case.”

Bernanke therefore defines a deflation as a generalized, broad-based, widespread decline in prices brought on by a severe drop in spending. The 425 bps of rate cuts in the Fed funds target during 2001 was presented as necessary to prevent a demand-lead deflationary spiral.

However, a simple decomposition of Bernanke’s favorite inflation measure, the PCE, for the bubble years 1996-2006 indicates that price declines were not broad-based, widespread, or “general”, but localized even as they introduced disinflation to the broad-based price indexes. Furthermore, there is evidence that demand by US-based economic agents did not drop below the level implied by full employment.

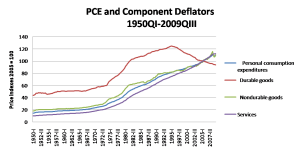

Chart (I) is of the PCE (and its components) price deflator(s). It clearly indicates that deflationary pressure was far from broad-based or generalized. The deflationary pressure was confined to the consumer durable goods component of PCE. The durable goods component had a weight between 12 to 13% during the period 2001-2006.

Chart I

The price indexes for the PCE and the non-durable goods components would have been weaker in the absence of the expansionary monetary policy of 2001. However, two points are clear:

1. the deflationary pressure was concentrated in the durable goods component, and

2. from 1996 to the present, the behavior of the price index for the durable goods component of PCE was largely independent of US economic performance, the overall PCE deflator, and the stance of monetary policy.

The behavior of prices during the period 1996-2006 does not fit Bernanke’s definition of deflation.

Was the decline in PCE Durable goods deflator reflective of a severe drop in spending?

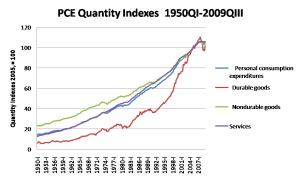

To answer this question we turn to the Quantity indexes for PCE and its components (Chart II).

During the period in question (1996-2006), the quantity index for the durable goods component of PCE indicates that the quantity of consumer durables goods purchased not only grew, it was the fastest-growing component of PCE.

Chart II

Lower prices and higher quantities are not consistent with a drop in demand and producers having to cut prices to find buyers. They are indicative of a positive supply shock – an outward shift of the supply curve in this case for consumer durables.

What about the supply-demand balance for the economy as a whole?

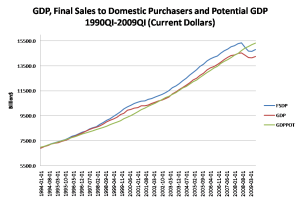

Chart III presents the Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers (C+G+G), GDP (aka Aggregate Demand –C+I+G+X-M) (both from FRED at the St Louis Fed), and potential GDP as estimated by the CBO (GDPPOT) (all series are in current Dollars). It indicates that demand or final products by US-based purchasers exceeded potential US output as estimated by the CBO for every year during the period in question.

Final Sales to Domestic Purchasers (FSDP) exceeded potential output (GDPPOT) in every year from 1995 to 2007– -and late in the period by over 6%. It also indicates that at the cycle trough in late 2002, the FSDP was still about 104% of GDP. Whatever ills the US economy experienced between 1996 and 2006, they were not because US economic agents weren’t spending enough to generate full employment.

Chart III

Given Bernanke’s definition of deflation, the US did not experience deflation at any point between 1996 and 2006, nor were there imminent bouts of deflation. Disinflation was localized in consumer durables and US economic agents remained willing to buy more than the US could produce. There was, however, a significant decline in the relative prices of consumer durables/tradable goods.

In so far as the interest rate reductions in 2001-2003 and the painfully slow tightening cycle that ended in 2006 reflected fear of a domestic demand induced deflation, monetary policy was inappropriate.

What was the underlying problem if it wasn’t insufficient US-based demand?

Three factors were responsible for the combination of disinflation and generally disappointing growth of output and employment. They were

1. globalization which lowered the prices of tradable goods,

2. a Dollar unable to adjust to maintain anything close to external balance, and

3. the absence of any developments or policies to promote/maintain US international competitiveness.

The US experienced disinflation and unemployment not because of a decline in the willingness of US-based economic agents to spend, i.e. the Bernanke explanation for deflation. Globalization was a shift in the world supply of tradable goods that lowered their prices. With the Dollar unable to adjust, some domestically produced, internationally tradable goods became non-competitive. US imports grew relative to US exports. The trade deficit/current account drove a progressively wider wedge between spending on final goods and services by US-based economic agents (FSDP) and the demand for US output (GDP).

Was US monetary policy inappropriate from 1996-2006, but especially 2001-2006?

The short answer: Yes.

Monetary policy is not a substitute for effective exchange rate and/or trade policies. Monetary policy cannot increase the prices of tradable goods and services relative to non-tradables. Monetary policy masked some of the symptoms resulting from globalization and the inability of the Dollar to adjust, but did nothing to correct the underlying problem.

During the period 1996 and 2006, there was a fundamental mismatch between the causes of the disinflation and unemployment and the policy steps taken in response. Policymakers employed the tools of counter-cyclical domestic aggregate demand management when the cause of the problems was a structural/permanent external supply shift. Policy in general – not just monetary policy – was inappropriate. Trade and Dollar/currency policy were inappropriate in that they failed to exist.

The policy mix gave rise to undesirable domestic side effects. Monetary policy does not affect the prices of non-tradables uniformly. Fed policy increased the demand for interest rate-sensitive goods such as housing and financial assets. The prolonged period of low rates altered investor and consumer behavior on a massive scale between 2001 and 2006. Fed policy incented economic agents to borrow short-term and buy real estate and financial assets. It incented financial firms to engage in regulatory avoidance and arbitrage, as well as to lobby regulators to relax limits on the sizes of balance sheets relative to capital. It also increased consumption and depressed savings through wealth effects.

At some point, certainly post-2002, someone at the Fed should have listened to the many voices that were issuing warnings about the growth of the unsustainable trade imbalance, the unsustainable decline in private savings, the unsustainable asset prices bubbles, and the increased use of leverage by financial institutions individually. Each of them implied that the “great moderation” wasn’t. At some point, someone at the Fed should have realized the short-term benefits arising from masking the symptoms of globalization were outweighed by the inevitable future costs.

In the mid 1990s the US faced a problem: a manageable trade imbalance. The Fed papered over the problem. Today we still have a trade imbalance, but it is coupled with 1) unemployment at 10%, 2) a severely crippled financial sector, 3) monetary policy at the limits of its usefulness, 4) consumer balance sheets in tatters, 5) state and local government balance sheets in tatters, and 6) a Federal deficit that is at a post-war record. I think it is safe to say that it was a bad trade.

Could the disinflationary effect of globalization be large enough to lead the Fed to set policy that was inappropriate for long-term economic and financial stability?

Given the rate of decline of the prices for consumer durables and the weight(s) attached to that component in the overall index, the deflation in consumer durables pulled the overall index down by about 50 bps each year. In a speech in 2005, Kohn said that research by economists at the BOG in Washington indicated that declines the prices of “tradable goods” reduced core (ex-food and energy) inflation by between 50 and 100 bps a year for the period (1996-2005) (allowing for some secondary effects). Needless to say, there is a good deal of overlap between durable goods and tradable goods.

Isn’t 50 or 100 bps a year to small to be a concern? Given that the Fed’s inflation target (PCE) is 2% (200 bps) per annum, but that the Fed was in a total and complete panic when PCE inflation was still above 1% (100 bps), 50-100 bps per annum was between half and the whole game.

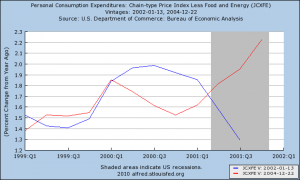

Chart IV

There was also a non-trivial measurement problem. Chart IV shows the reported PCE deflator, ex-food and energy, as it was initially reported at the beginning of 2002 (in blue) and how it was reported after revisions at the end of 2004 (in red). (Data from ALFRED at the St Louis Fed)

Between globalization-driven declines in the prices of tradable goods and the measurement error reported above, it is very likely that the Fed cut rates too much too fast, and by doing so, set the stage for too low too long.

What does this imply for economic policy going forward?

With the current account deficit still in the neighborhood of 3% of GDP and the consumer sector having decided to save and rebuild its balance sheet, the argument that classic Keynesian stimulus will relatively quickly generate a self-reinforcing, sustainable recovery that achieves full employment is nonsense.

There is no reason to assume that self-reinforcing, satisfactory growth will be achieved until external balance is restored and balance sheets are rebuilt.

Given the likely structural “drags” from the trade and consumer sectors, debt-financed stimulus spending will be nothing more than a short-term palliative that will generate higher debt levels relative to income without correcting the underlying problems. Palliatives are in order, but policymakers should not pursue palliatives to the exclusion of curatives.

To bring about sustainable growth, policy must encourage the redirection of resources away from the production of non-tradable goods and services and toward both the production of tradable goods and investment, especially in manufacture of tradable goods. Policymakers must also take steps to make sure US manufactured tradable goods are competitive enough on world markets to restore a sustainable external deficit, if not external balance. Households must be able to rebuild their balances sheets.

Unfortunately, to date, US policy is currently directed at promoting:

1. consumption -at the expense of savings,

2. pegging asset prices (Japanese-style PKOs),

3. promoting investment in housing which does not generate jobs for the life of the investment (as plant and equipment investment can) or contribute to a narrowing of the external imbalance,

4. reducing US competitiveness via regulation and taxation,

5. ignoring the external sector and problems of competitiveness completely, and

6. subsidizing producers of tradable goods and services that failed the market test, but not supporting firms that have passed the test.

US households, labor, businesses and financial firms have all altered their behavior in light of globalization. Only US policymakers continue to behave as if US prices, output, and income are entirely determined domestically.

How did we wind up in this mess?

There are numerous reasons. Macro-economic policy, especially monetary policy, has been sold as a cure-all. If you look at all the partisan and ideological positions taken by economic policymakers, economists, pundits, etc., they start out with very different policy prescriptions, but end with the same conclusion: follow my advice and everyone will live happily ever after. Given the degree of confidence with which they are expressed, they are all fairy tales. There are limits to what policy can achieve. Once again, policymakers tried to fine tune the economy, only to create problems.

It is not simply a lack of tools, regulatory or otherwise. There has been an almost total absence of leadership. Policy has been short-sighted and myopic. There has been no willingness to endure any short-term pain regardless of potential future benefits.

Mr Alford says: “To bring about sustainable growth, policy must encourage the redirection of resources away from the production of non-tradable goods and services and toward both the production of tradable goods and investment, especially in manufacture of tradable goods. Policymakers must also take steps to make sure US manufactured tradable goods are competitive enough on world markets to restore a sustainable external deficit, if not external balance. Households must be able to rebuild their balances sheets”.

I have just been on a thread at another blog where a commenter asked (in effect) why, if there has been easy, cheap money around for a while, hasn’t there been a general inflation. My response was – the War on Labour. By depressing household incomes, reducing savings and encouraging people to borrow in order to consume, policy prevented consumer price inflation while eccouraging asset price inflation. Asset price inflation was a result of easy and cheap money plus the boom in credit, leverage and speculation associated with the substitution of credit for earned income. And it massively diverted resources from productive investment.

Now Mr Alford is making suggestions about sustainable growth based on manufacturing tradable goods. I don’t think that’s possible without ending the War on Labour. You are going to need, besides a much better industrial policy, a manufacturing workforce which can support the competitive manufacturing sector you want.

That this is possible is a lesson of the US’ own history – just look back a few decades. But it’s not going to happen until people can support themselves by working and they have confidence that there are good jobs out there which are going to be around for a while.

gordon,

You say that “policy prevented consumer price inflation,” but I believe Alford amply demonstrated that this statement is factually incorrect. The only place where there has not been inflation is in durable goods. If you look at everything else, or as my brother puts it, “the things you have to have in order to live”–food, energy, healthcare, shelter–there has been considerable inflation.

I share your concern for the plight of the American worker. However, unless policy actions are taken to ameliorate the trade and current account balances, how can their ever be any hope for the American worker?

If you want to take care of the American worker, then you have to take care of him/her. If you want to take care of the trade balance, you should do that.

But don’t suggest that fixing the one will help the other. Decide which is the important factor.

At least, treat the American worker with enough respect as to admit that his/her situation will again be sacrificed to fix the trade deficit as it was sacrificed on the altar of free trade…

The reason why the US is a consumer economy is because of the Federal Reserve’s easy money that allows consumer credit. The past decade, or so, real wages never increased, but their debt has. Now you got people saying the depreciated dollar is making manufacturing go up. This is incorrect as the US dollar is still the reserve currency, and still more valuable currency out there. Zimbabwe currency is worth zero, yet you don’t see corporations from all over the world flocking there. There is other factors, but it goes back to the core of aggregate demand, and production. Other countries such as China have credit expansion where it allows previously savings glut countries to be more attractive to exporters. The US consumer has easy money to consume, and willing to consume on debt. Real wages, real cost of goods, access to resources, and savings are factors in deciding intertwined global economics. Even if a country devalues it’s currency consistently, if the country it exports to has a savings glut, it won’t work, because the consumer is simply not spending. Consumer credit rises the prices of goods generally as banks charge fees to merchants who accept credit cards.

i appreciate your observations.

however, i do not think manufacturing is the key to growth, particularly with respect to employment.

this is a sector which has a structural tendency towards dwindling employment due to productivity increases. china has all the manufacturing capacity we could dream of; so much so that there is a glut of it. adding to this glut seems problematic to me, especially since the US would be priced out of the industry. never mind the extraordinary capital expenditures necessary needed to be relevant in such a capital intensive sector.

we might as well try to spur employment growth in agriculture, despite tractors, combines, grain elevators, harvesters, etc…

There is no technical basis for China to succeed as a competitor against the US – none, nada, zip, zilch…

Any nation that spends 48 percent of its working time putting food on the table cannot compete with a country which devotes less than one percent of it time doing so. Manufacturing is in China because the US businesses sent it there.

question: in order to avoid the key problem which is not a war on labor but global labor arbitrage wldnt it ultimately require either a closing of national borders – ie return to marcantilism – or else a stop gap on global polulation growth ? For as long as asia creates in excess of 20 million new entrants to be integrated into the global workforce – america and the rest of the world will never find a working mechanics to expand the labaor market via demand by the requireed speed (growth) – whcih brings us to Big AL (Greenspan) practical receipy which was driven by simple realities ?? – push growth like mad and create jobs at utmost speed regardlos of location and then use excess tax revenues to pay for those unfortunate minortie which do not manage to get a job ?

Thank you for this posting. I have felt for some time that trade policy was at least as large a factor in the current US economic malaise as monetary policy but I lack the knowledge to articulate such an argument in any detail. Thankfully, you have been able to do that quite convincingly.

As for those who denounce protectionism in all cases, I would submit that protectionism is the economic equivalent of war, and that any blanket denunciation of protectionism is tantamount to economic pacifism. Now there is no question that war, just like protectionism, is hell, but most observers understand that any unilateral renunciation of the use of military force will only encourage other actors to launch aggressive wars of conquest. Sure, small isolated countries can get away for a while with pacifistic policies because they benefit indirectly from the military power of their neighbours or they provide a niche service vital to all. But historically, most nations have needed to maintain military forces to dissuade possible wars of aggression being launched by their neighbours.

Of course most, if not all, reasonable actors would prefer a state of peace / free trade but in order to achieve this state of affairs, war / protectionism must be maintained as an option to dissuade possible aggressors.

And what is vital in maintaining peace / free trade is to immediately punish acts of aggression / protectionism.

But whereas acts of war are relatively easy to recognize and define (naval blockades being the ambiguous exception) acts of protectionism can be more difficult to ascertain. To begin with the boundary between free trade and protectionism will never be a clean and straight line. For example, the banning of goods produced by child labour will always be a possible source of ambiguity, not to mention environmental standards, labour conditions, and consumer protection issues. In order to avoid a race to the bottom, and since the richer nations are the ones who hold the economic power to which the poorer countries aspire to reach; it will be the wealthy nations who decide exactly where the line is to be drawn between free trade and protection.

But current ambiguities withstanding, there is no doubt that the protectionist policies of many Asian nations deserve a robust response by US policy makers. But this response is not to be expected any time soon. The problem is that American elites profit handsomely from the inbalances created. But more importatly, our elites leverage access to US markets for gains in their quest to make America the global Hobbesian sovereign. In this situation, the interests of the great masses come a distant second to elite dreams of global hegemony. While US elites will not lift a finger in reaction to Chinese protectionism, if the Chinese were to break the self-proclaimed American monopoly on international military violence, or take serious steps (beyond lip service for internal consumption) to weaken the status of the dollar as the global reserve currency, then we would see a much sharper reaction for our elites, for these types of moves would represent a real threat to US global hegemony.

But the end of the day, as it always has through history in every country, it comes down to a struggle between the interests of the elite versus the masses. Unfortunately, for the last thirty years or so, in the US at least, there has not even been a contest, as the increasingly sharp knife of the US elites continues to cut through the ever softening butter of the masses with ease.

Kevin de Bruxelles,

I agree that this is an extremely thoughtful and information-packed post. I find it most interesting because it offers an exceedingly intelligent response, as well as nice addition to, Marshall Auerback’s Keynesian prescriptions.

But it lacks your and Auerback’s hard-hitting insights as to how we got here. We arrived at this dismal state because of deliberate and malicious acts of arrogance and stupidity on the part of an American elite overly hungry for money and power. It is the much-feared boomerang of the “government of subject races” (Lord Cromer) on the home government during an imperialist era. It means that rule by violence in faraway lands ends up affecting the government of the United States, that the last “subject race” will be the Americans themselves.

My sister has always been an avid bridge player, which somehow has always allowed her to worm her way into social circles far above her actual socio-economic rank. My brother-in-law was an anesthesiologist and an Army colonel stationed in Honolulu. I was just a kid visiting my sister and brother-in-law, maybe 18 or 19 years-old at the time, and can remember being invited one evening for dinner to one of the top military commander’s beautiful home, high up on a hill overlooking Honolulu bay. And I will never forget what he told me: “All wars are fought for markets.”

Oh, well, those were the halcyon days before McNamara, Cheney and Rumsfield, back when American military engagement was about real politic.

All that has changed now. As Hannah Arendt pointed out in Crises of the Republic, starting with the Viet Nam War:

The ultimate aim was neither power nor profit. Nor was it even influence in the world in order to serve particular, tangible interests for the sake of prestige, an image of the “greatest power in the world,” was needed and purposefully used. The goal was now the image itself, as is manifest in the very language of the problem solvers, with their “scenarios” and “audiences,” borrowed from the theater. For this ultimate aim, all policies became short-term interchangeable means, until finally, when all signs pointed to defeat in the war of attrition, the goal was no longer one of avoiding humiliating defeat but of finding ways and means to avoid admitting it and “save face.”

Image-making as global policy—not world conquest, but victory in battle “to win the people’s minds”—is indeed something new in the huge arsenal of human follies recorded in history.

Or as Auerback pointed out:

The U.S. has been perfectly happy to accede to the current state of affairs in spite of the immense economic damage it has inflicted on the domestic manufacturing sector (and the concomitant evisceration of its middle class) because it has provided the country with a cheap form of war finance…

http://www.pimco.com/LeftNav/Viewpoints/2007/Renegade+Economics.htm

“All wars are fought for markets”, if true, would have left the US with a good export position. At the end of WWII the US was the only industrialised country with an intact infrastructure. That should have been the basis for overwhelming penetration of foreign markets, constrained only by availability of credit. And yet now we see the US with a big export deficit.

Of course, no recovering European country or Japan would have wanted (or, really, been able) to tolerate continuing deficits with the US, so considerable compromises would have been necessary over time. But still, one would have expected a better contemporary situation than we see at present.

And in regards to your assertion that “protectionism is the economic equivalent of war,” here’s a quote you might find germane:

In the profession of war the rules of the art are never violated without drawing punishment from the enemy, who is delighted to find us at fault.

–Frederick the Great

I pretty much agree with this assessment and there are two key statements for me.

Only US policymakers continue to behave as if US prices, output, and income are entirely determined domestically.

Policy has been short-sighted and myopic. There has been no willingness to endure any short-term pain regardless of potential future benefits.

What this does though is to not only point the finger at the FED but at treasury policies as well.I was also interested in the following comment from Kohn’s speech.

But from another perspective, integrated economies and financial markets can also exert powerful feedback, which may be less forgiving of any perceived policy error. For example, if financial market participants thought that the Federal Reserve were not dedicated to maintaining long-run price stability, they would be less willing to hold dollar-denominated assets and the resulting decline in the exchange value of the dollar would tend to add to inflationary pressures.

Is stagflation around the corner with the current Fed Policies ?

Kevin de Bruxelles is right to say that there is no clear and straight line between free trade and protectionism, provided he means that international trade is a matter of give and take. A continuing large trade imbalance with one country must be compensated by surpluses somewhere else, or that imbalance will have to be rectified.

The only exception to that rule is a country where trade is a very small proportion of national income. That used to be true of the US up until very recently, and I suspect current difficulties in the US with the idea of trade really arise from the fact that living in a trade-exposed economy is a new experience for US policymakers – compared, eg. to Germany, where trade has been vital for generations.

The same remark applies to Wolf’s reference to mercantilism. Everybody can be mercantilist provided that everybody realises that none of the players can run a perennial overall deficit forever. The result is a practical willingness to compromise.

I don’t know why Kevin de Bruxelles thinks that naval blockades aren’t unambiguously acts of war. I would have thought they obviously are. Is this an attempt to excuse eg. sanctions on Iran?

No, in terms of naval blockades I am thinking particularly about Egypt’s closing of the Straits of Tiran to Israeli shipping in 1967, but I am sure there are other examples. The reason that they are ambiguous is that no actual violence is needed to enact them. So for example who really started the 1967 war, Egypt with its blockade of the Red Sea on May 23rd or Israel with its air attack on June 5th? Since it’s called the Six Day war and it ended on June 10, I would think it was the air attack, although most would certainly consider Egypt’s naval move as an act of war. Therein lies the ambiguity.

Might I add the US blockade of Japan prior to the onset of hostility’s, snicker…

and the blockade of Cuba, it was an act of war but we call the whole affair the Cuban Missle Crisis, not the Cuban Missile War!

If this splendid critique does not kill off Bernanke and all the other patsy academic/econ consulting firms who slavishly echo Fed and government predictions with their failed models, then nothing will.

Nothing will. They are the living dead – intent on eating the brains of undergraduate students…

Superb, fun to read, still digesting. I’ve been a “FED watcher” since Arthur Burns. Your definitions of “tight” and “easy” monetary are inaccurate: Low interest rates are indicative of a “tight” monetary policy & high rates are associated with an “easy” monetary policy.

A clear distinction should be made between the temporary and the longer term effects of open market operations on the level of interest rates. To hold down the Fed Funds rate (and other rates through this key rate), the Manager of the Open Market Account puts through buy orders for T-Bills or other eligible securities sufficient to yield a net increase in costless, member bank reserves and costless excess reserves. The Fed acquires these earning assets by creating costless, new interbank demand deposits in the Federal Reserve Banks—that is by creating costless, new legal reserves at the disposal of the member banks.

Assume the buy order is for T-Bills. The effect is to bid up their prices, reduce their discounts (interest rates) and add to member bank legal and excess reserves. The expansion of free excess reserves increases the quantity of loan able “federal” funds thereby pegging or retarding the increase in the Fed Funds rate but the longer term effects of these operations are to fuel the fires of inflation.

Aggregate monetary demand is equal to monetary flows (our means of payment money, times its rate of turnover).

MONETARISM HAS NEVER BEEN TRIED: To counter what Greenspan described as “irrational exuberance” (at the height of the Doc.com stock market bubble), Greenspan initiated a “tight” monetary policy (for 31 out of 34 months). A “tight” money policy is one where the rate-of-change in monetary flows (our means-of-payment money times its rate of turnover) is no greater than 2-3% above the rate-of-change in real output.

Greenspan then wildly reversed his “tight” money policy (at that point Greenspan was well behind the employment curve), and reverted to a very “easy” monetary policy — for 41 consecutive months (despite 17 raises in the FFR-every single rate increase was behind the curve).

Then, as soon as Bernanke was appointed to the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, he initiated a “tight” money policy, for 29 consecutive months (out of a possible 29, or sufficient to wring inflation out of the economy). For the last 15 successive months (since Aug 2008), the FED has been on a monetary binge.

Did you catch it??? Nobody got it. Greenspan didn’t start “easing” on January 3, 2000, when the FFR was first lowered by 1/2, to 6%. Greenspan didn’t change from a “tight” monetary policy, to an “easier” monetary policy, until after 11 reductions in the FFR, ending just before the reduction on November 6, 2002 @ 1 & 1/4%.

I.e., Greenspan was responsible for both high employment (June 2003, @ 6.3%), and high inflation. The evidence of Greenspan’s inflation (rampant real-estate speculation, followed by widespread commodity speculation – peaking in August 2007), just cannot be conclusively deduced from the monthly changes in the price indices. And because of monetary lags, Greenspan’s legacy extends into 2010, with the creation of even higher unemployment (10.0%).

Part of the problem is the FED’s dual mandate; as the last reduction in the FFR occurred in the same month as the peak rate in unemployment (June 25, 2003). The FED can only hope to achieve stable rates of inflation. It’s employment mandate is unachievable.

What? How many T-Bills does the “trading desk” have to buy before it is able to reduce the unemployment rate by 1%? Of course, this is utter naiveté.

THE POINTS ARE: GREENSPAN

(1) DID NOT EASE UNTIL OCTOBER 2002 (DESPITE 11 FFR CASCADING PEGS, BEGINNING ON JANUARY 3, 2000.

(2) DID NOT TIGHTEN MONETARY POLICY AT ALL, EVER! (DESPITE 17 STAIR STEPPING FFR PEGS)

Unfortunately the Federal Reserve doesn’t gauge the volume and timing of its open market operations in terms of the amount and desired rate of increase of member commercial banks COSTLESS legal reserves, but rather in terms of the levels of the federal funds rates (the interest rates banks charge other banks on excess balances with the Federal Reserve).

By using the wrong criteria (interest rates, rather than member bank reserves) in formulating and executing monetary policy, the Federal Reserve became the bubble’s engine.

Flow5,

You scream at us that “MONETARISM HAS NEVER BEEN TRIED.”

I believe this is what Alford Is referring to when he says: “Macro-economic policy, especially monetary policy, has been sold as a cure-all.”

It’s the Libertarian-Austrian-Neoliberal canon, no? Free trade absolutism. Free capital flows absolutism. Deregulatory absolutism. Monetary policy is the talisman of the Libertarian-Austrian-Neoliberal axis. Get that right, and all other economic evils magically disappear.

And by the way, as Paul Krugman points out in this essay, your assertion that “monetarism has never been tried” is factually incorrect:

Monetarism was a powerful force in economic debate for about three decades after Friedman first propounded the doctrine in his 1959 book “A Program for Monetary Stability.” Today, however, it is a shadow of its former self, for two main reasons.

First, when the United States and the United Kingdom tried to put monetarism into practice at the end of the 1970s, both experienced dismal results: in each country steady growth in the money supply failed to prevent severe recessions. The Federal Reserve officially adopted Friedman-type monetary targets in 1979, but effectively abandoned them in 1982 when the unemployment rate went into double digits.

http://www.nybooks.com/articles/19857

Monetarism was attempted, both under Thatcher and by Volcker. Why has it never been attempted since? Because, contra the claims of its adherents. the relationship between money supply growth and ALL other economic variables quickly became wildly erratic.

It’s a good piece. Off the top of my head I can offer several thoughts on it.

First, his set up is disingenuous. This post establishes that interest rates were “too low for too long” (from 1996-2006) while dispensing with the Taylor Rule and its sensitivity to choices of inputs and assumptions. Sorry, but the second he uses this variable (potential GDP as estimated by the CBO (GDPPOT) he is essentially Taylor rule. The Taylor rule in essence is a balancing of the ‘output gap’ versus inflation, a variant of Okun’s Law. You can easily note that he is confronting the output gap and issue of inflation, just separating out the components.

Second, if memory serves (don’t have the time/interest to data mine right now), a large element of the disinflationary forces during this period arose from technological advances (think the PC and software as a prime example). That would be interrelated with durable goods to some degree and also with offshoring production, but it is a distinct element. This point does not detract from the probability that incorrect policies were specified at the time. However, unless you unravel the components, identifying trade, industrial and dollar policies as the elixir might also represent incorrect prescriptions.

Third, he really does not elaborate on what should have been done/could be done. The policy variables he identifies are too generic to really dissect. We tried some of those things in the 30s and they didn’t work too well. Japan carried some of them to the umpteenth degree (remember MITI?) and look where it got them. Things like industrial policy and currency pegging may work in a developing country for awhile if other nations acquiesce, but they are not long term solutions available to all nations. China will be discovering this fact in the not too distant future.

Still, a useful piece if for no other reason than highlighting that monetary and fiscal policy are not curatives for all ills and that we are in the process of generating more policy errors.

Dean,

You are about a decade late in your attribution of deflationary forces to computers. The biggest factor in that timeframe was the widespread adoption of Wal-Mart’s retail practices. both in the way it managed its supply chain and the use of offshore vendors. McKinsey has written a lot about this.

I believe I said technology and merely used computers as an example. Somehow I think without the improved technology WalMart would not have been able to do what you reference. And your comment does not even address the point, you merely offer a different source. Was the disinflation caused by factors other than what the author attributes.

I can’t believe the Fed Chairman does not know what deflation is!

Conjecture holds the Fed creates credit – moneylike claims against production. This is wrong, the Fed creates currency while finance creates credit in all its iterations. The notion that the Fed or any central bank can ‘control’ deflation or do something to stop it is fantasy. Deflation – like inflation – are artifacts of production, money/credit velocity and large public participation. Deflation originates in forces that propel production.

The developed and developing world is experiencing a deflationary energy crisis not a credit crisis.

Bernanke simplemindedly suggests a decline in prices represents deflation. Rather, deflation is the shrinkage of available credit and money. Cash being very difficult to obtain or hold and there is a widespread and general revulsion against credit by both lenders and borrowers.

Irving Fisher in the 1930’s made the best description of deflation which is a dynamic, rather than static condition. Deflation feeds on itself.

Money aggregates are shrinking worldwide except in China where a command economy is able to force lending. The reasonable outcome in China is hyperinflation first which drives citizens into hedging assets; this leading to a deflationary crash afterwards. In the US and the West, the deflation will arrive now with a total revulsion against assets of all kinds followed by hyperinflation as the last act of governments at war against their own peoples.

Bernanke does not understand the relationship between energy prices and deflation; he does not understand the deflationary or hard currency outcome of Saudi Arabia pegging the dollar to crude.

Increasing oil prices ‘strand’ oil- dependent infrastructure. Our oil platform is designed and built around $20 a barrel crude. As oil is central to all economic activities in our country, the rise in price is a credit- mediated form of energy shortage.

Rather, an energy shortage mediated/rationed by credit availability. As oil becomes less available it forces capital allocation away from productive enterprises and toward itself. Our ‘growth’ is flowing to Riyadh, which sets economic policy for this country.

The US is rapidly becoming an energy pauper. Credit can conceal for a time but not eliminate this situation.

By pegging the oil/dollar trade @ $70- 80 a barrel. A declining dollar (or de facto devaluation) would leave crude increasing in dollar terms; the Saudis have fixed the price within a trading range to effectively create a hard dollar. This has happened several times over the past six months and is taking place currently.

Bernanke’s tactic has been to destroy the dollar’s value to drive holders of cash toward risk, the Saudi oil minister has rendered this tactic useless. The dollar is worth something – a half gallon of crude oil – and is thus too valuable to short.

Recent dollar firmness is noticeable in currency exchange and the oil peg in my opinion is the reason why. As more and more traders become aware of this peg, the short- dollar strategies will become increasingly risky. The Saudis have called Bernanke’s bluff; he has failed, he has nothing, Saudi minister Ali al- Naimi has crude oil.

The historically wide Treasury yield curve represents more Bernanke stupidity. The market rise in yields outside the Fed’s administrative ambit suggests to me that the Fed is in danger of losing control of short term rates. The Fed can only defend short rates and cannot control risks associated with these rates. A best case scenario has the Fed becoming completely irrelevant … exactly when Fed intervention becomes required as when there is a run against money- market accounts and market rates skyrocket.

Going long on the dollar shorts Bernanke. He’s incompetent and should be fired. Why it’s taken so long is another indicator of how broken this country’s establishment is.

What a marvelous blog. It should be part of the curriculum at all schools of economics. There is no better source for pertinent information anywhere.

“Deregulation” of capital markets has allowed the casino ethos to take over from the investment ethos. When you can make long term loosing bets but collect huge artificial winnings simply by describing a winning hand, which is exactly what Banking pay has done for the last decade, the actual risk involved in making actual investments in actual productivity and wealth creation in the real economy looks way too risky!

Good show! Wonderful!

I agree with Independent Accountant.

Thank You for posting this rational, well-thought-out, article. It’s always occurred to me as strange that the Fed acts as tho globalization never occurred, and “behave(s) as if US prices, output, and income are entirely determined domestically.” Mr. Alford is one of the only voices I’ve heard raised to point out the obvious disconnect between the two policies.

Thanks again for posting what I never would have found on my own.

“To bring about sustainable growth, policy must encourage the redirection of resources away from the production of non-tradable goods and services and toward both the production of tradable goods and investment, especially in manufacture of tradable goods.”

Oh please…who is the US going to sell to? Europe and Japan? Their demand is imploding. China? If you want to sell to that market they demand you manufacture in the local market. Emerging markets? Hard to compete with China for barebones consumer goods.

And who is going to innovate all these products the US will export? Does anyone in Washington even know how to create and industrial policy? In the US the best and brightest go into the FIRE sectors. Manufacturing is for grunts. Usury pays so well nowdays.

Africa could use everything – If the price was right. Most living in the less devloped regions of the world could use potable water located conveniently to where they live. There is a crying need for modern agricultural machinery almost everywhere.

(That is, if anyone were interested in doing anything more than selling Americans a third car.)

“Does anyone in Washington even know how to create and industrial policy?”

Why, yes. Look at subsidies, tax breaks and earmarks. Those are some of the tools of industrial policy (only some) and they are regularly deployed. Then at the State level you have more, including locational incentives. Even municipalities get in on that one.

It’s not that the US doesn’t have an industrial policy; it’s just incoherent and untargeted and corrupt.

With the Dollar unable to adjust, some domestically produced, internationally tradable goods became non-competitive. US imports grew relative to US exports. The trade deficit/current account drove a progressively wider wedge between spending on final goods and services by US-based economic agents (FSDP) and the demand for US output (GDP).”

Please….show me ONE case in the past 30 years where a declining dollar allow the US to compete once again in an industry that was lost to foreign rivals?

Furniture manufacturing is making a serious comeback.

What a great article. Exactly on point.

Monetary policy of the Federal Reserve can not mix structural problems and when it is attempted will usually result in negative outcomes.

I have said for a long time, put the best Central Bankers (compared to the losers we have currently) in place in Somali and the best monetary policies will not fix their problems. Why, they have structural problems.

The continual attempts to fix structural problems through monetary policy just ends up with negative outcomes.

Oops, typo. I meant “fix” not mix.

Ben Bernanke doesn’t know what he is talking about, and this is coming from a guy who is rather uneducated. It’s the inflation threat, really.

I also wonder to what degree the low interest rate policy depressed consumption by savers who had been getting 5% but were fleeced down to 0%.

Some of this wealth went out the yield curve and down the risk curve in search of higher income — and got vaporized. Like auction rate securities and etc.

So not only wasn’t that income available for consumption, but it was wealth that got toasted. In its place, for a while, debt-fueled consumption filled the gap.

But now we’ve lost the wealth and we’ve lost the debt fueled consumption. And all because of low interest rates that fueled malinvestment that resulted in wealth destruction.

It seems to me that Professor Bernanke means well, but he is like a deluded Scientologist who believes that L. Ron Hubbard was a Messiah and that engrams are the problem for all psychological maladies. It may be hypocritical of me to say something like that, given what I believe about how the universe works, but at least my world is based on direct observation and the candidate pursuit of truth — in the great Jeffersonian tradition. I believe that Dr. Bernanke’s world view was formed in a library and a lecture hall, where reality is very far away and the force of the morphic fields are very strong. This is essentially an anthropologicasl problem and one of group psychology–as is the problem of consumption in developing nations.

Clearly the end game of the low interest rate theory is that growing middle classes in developing nations will become markets for American exporters. This presumes a number of assumptions about cultural psychology that are questionable — even though I’ve argued this same point in the past, for fun. Never the less, our consumption preferences aren’t inherently universal. Nor our our spending preferences. It amuses me to see American leaders chide the Asians for “excess savings”, as if what they do with their money isn’t their business and there is some sort of moral component to retaining it that borders on “hoarding”. Don’t bogar that joint, my friend, pass it over to me . . . ha ha ha.

What a ridiculous joke all this is. Really. It would be a good laugh if it weren’t so deadly.

You should look at capacity destruction which takes place in 2003-2004, and again flares in 2009. This would seem to confirm the conclusions of this article. A generalized glut of capacity occurred, and the response in the US was the loss of manufacturing capacity.

In short, as I continue to insist, hours of work must be reduced. Without it, the alternatives are those cited in the article: exchange rate manipulation and protectionism.

Yves Smith & DownSouth:

I never said monetary policy is a cure all. But Krugman is very ignorant, and knows very little, of monetarism. And anyone that professes that Volcker’s experiment in the period 79-82 reflected monetarism, is also, extremely ignorant.

I called the AAA corporate bond bottom (in Sept 81), in the exact month & within one basis point (of course being so close was pure luck but based on sound theory).

I’ve never read an economic research paper that used the correct figures, let alone the correct calculations. And you can no longer retrieve the correct numbers, except in the Federal Reserve Bulletin (as the revisions overlay the old data).

And monetarism didn’t start with Friedman. Monetarism has never been tried.

MONETARISM HAS NEVER BEEN TRIED:

(1) Paul Volcker, Chairman of the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, appeared before the House Domestic Monetary Policy Subcommittee. In response to a question as to why the Fed had supplied an excessive volume of legal reserves to the member banks in the third quarter 1980 (annual rate of increase 13.2%), Volcker’s defense was that there are two types of legal reserves; 1) borrowed (reserves obtained by the banks through the Federal Reserve Bank discount windows — in October they borrowed 3 billion dollars at up to 20 percent), and 2) non-borrowed (reserves supplied the banking system consequent to open market purchases).

Volcker advised the congressmen to watch the non-borrowed reserves—“What we do on our own initiative.” The Chairman further added — “Relatively large borrowing (by the banks form the Fed) exerts a lot of restraint.”

This is, of course, economic nonsense. One dollar of borrowed reserves provides the same legal-economic base for the expansion of money as one dollar of non-borrowed reserves. The fact that advances had to be repaid in 15 days is immaterial. A new advance could be obtained, or the borrowing bank replaced by other borrowing banks. The importance of controlling borrowed reserves is indicated by the fact that at times nearly 10% of all legal reserves were borrowed.

(2) Monetarism involves controlling the volume of total reserves, not the volume of non-borrowed reserves as administered by Paul Volcker. Monetarism has never been tried.

Forgot, the Board of Governors figures are in the Federal Reserve Bulletin. I used the figures from the Federal Reserve BAnk of St. Louis (they are more accurate, and I can’t find them, they have been wiped out? with Anderson’s & Rasche’s revision to reserves and the monetary base).

(2) As of the March 31st 1980, when the DIDMCA went into effect, total reserves, by the end of DEC 1980, grew at a 17% annual rate-of-change.

(3) Then, on January 1st 1981, NOW & ATS accounts were authorized (Any institution whose liabilities can be transferred on demand, without notice, and without income penalty, via negotiable types of credit instruments, and whose deposits are regarded by the public as money, can create new money, provided that the institution is not encountering a negative cash flow).

(4) Volcker set off this “time bomb” (all the demand drafts drawn on the depository institutions enumerated in the DIDMCA, cleared through demand deposits – except those drawn on MSBs, interbank and the U.S. government.

(5) (Vt), in conjunction with an excessive rate-of-increase in legal reserves, was responsible for the 19.2% increase in nominal GNP (10% inflation) during the 1st quarter of 1981.

The importance of Vt (the transactions velocity of money –bank debits) in formulating – or appraising monetary policy derives from the obvious fact that it is not the volume of money which determines prices and inflation rates, but rather the volume of monetary flows (MVt) (our means-of-payment money, times its rate of turnover) relative to the volume of goods and services offered in exchange.

(4) (Vt) vaulted from .02% rate-of-change in May of 1980 to a 37% rate-of-change in May of 1981. I could of course, write a book.

A brilliant post – logical, articulate and significant – and hopefully I don’t say that just because I agree with it!

Yves,

Alford proves that Bernanke’s justification has no basis in reality.

However, this is not an inappropriate monetary policy, complicated by the lack of a trade and currency policy as Alford argues. It is a policy designed to support capital flight to China. The trade policy and currency policy is one which supports that flight, while interest rate policies are supporting domestic demand.