One of the impediments to getting to the bottom of the financial crisis is some of the most destructive behavior involved complex instruments like collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps. It isn’t simply that these “innovations” had terms and features that differ from familiar investments like stocks and bonds, but the way those instruments were used, both the trading/investment strategies and transaction mechanics, also differs from those of more traditional instruments.

This matters because it is very easy to go off half cocked, and that in the end serves the financial services industry, not the cause of reform.

I assume most if not all readers are upset about the sorts of things that happened and are happening in finance. But we need to remember what we are up against. The lobbyists paid by the financial services industry to kill reform are professionals. And so far, they have done a very effective job.

So even though the enthusiasm for identifying suspicious-looking activity is understandable, if the pro-reform camp is not careful and pursues flights of fancy that are unsupported by hard evidence, or simply overstates what it has proven, then it plays into the hands of banking industry lobbyists. It makes it easy for them to paint critics as not credible, thereby hurting efforts to rein in the industry.

Some of the discussion around the Fed/AIG chicanery falls into this camp. Now it seems almost without question that if more rocks were turned over at AIG, more creepy crawlies would emerge. Why had the Fed gone to such lengths to keep transaction-level detail at Maiden Lane III secret? Why were those CDOs bought at all? Why was Goldman so heavily involved in these transactions (both directly, via CDS it had with AIG, and indirectly, via CDOs it had created but were held by other banks?). Many of these deals were created when Paulson was CEO of Goldman; why hasn’t this aspect of his many conflicts in dealing with his former firm been probed more deeply?

And where was the Fed? CDS were a known systemic risk as of the Bear rescue; any reasonable look at that market would have led straight to AIG. The “we weren’t their regulator” excuse is spurious; they regulated AIG’s counterparties and could easily have connected the dots, particularly since the monolines were on the ropes as of early 2008.

That’s a mere starter list, but it illustrates that there are many fruitful lines of inquiry on the AIG/Fed front. But then we have some lines of attack that are wide of the mark.

I hate personalizing this discussion, but one example comes in a series of posts by David Fiderer. He’s tried digging into AIG transaction details, which is a worthwhile undertaking. However, his eagerness to come up with attention-grabbers had led him to make charges that are contradicted by other evidence or CDO market practice. While he has raised some questions, unfortunately, they do not shed any new light on these bigger, more pressing issues and may in fact confuse them.

Let’s take some examples from a recent post, starting at the top:

Did Societe Generale ever view its $1.2 billion investment in Adirondack 2005-2 as a buy-and-hold proposition? Or was the bank’s original intention to offload the risk on to AIG? The answer is central to our understanding of the portfolio of collateralized debt obligations, or CDOs, that wiped out the insurance behemoth. The circumstances of SG’s, and other banks’, holdings, suggest that CDO market was a Potemkin’s Village, a facade constructed to give the illusion of economic substance to a series of sham transactions.

Huh? These transactions in the end proved to be colossally stupid, both from the AIG and the SocGen perspective, but you need a lot more to prove nefarious intent.

First, buyers of AAA tranches of CDOs often got credit protection. That alone should in theory raise eyebrows, but it was hardly unusual, let alone devoius, particularly when the packager/guarantor that retained the position was a European bank. It was very common for European banks to hang on to the AAA tranches of CDOs, both those made primarily of residential real estate (called ABS, for asset backed securities, CDOs) and commercial real estate (CRE CDOs). Why? They had a great deal of latitude in how much (meaning how little) equity they were required to hold against AAA paper under Basel II rules, and when they hedged AAA paper with an insurance policy from an AAA counterparty like AIG, they held no equity against the position (and some banks even gave favorable treatment to guarantees from lower-rated insurers like ACA).

This regulatory capital treatment led to a good deal of behavior that was dysfunctional and destructive, but to suggest it was unusual is simply incorrect.

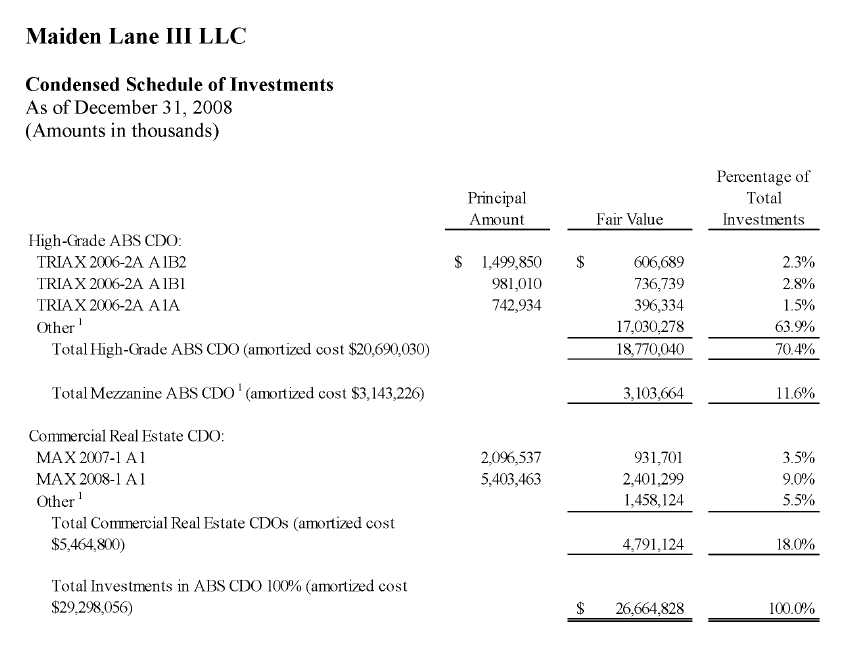

In keeping, Fiderer has focused on the largest CDOs that ultimately were bought by the Fed via Maiden Lane III. These were two transactions, MAX 2007 1 A-1 and MAX 2008 1 A-1, each disclosed in the Maiden Lane III financial statements, both commercial real estate CDOs (thus not part of the infamous “multi sector CDO portfolio”, click to view full image):

The biggest and most obvious example, disclosed last May, was Max 1. Deutsche Bank underwrote the $5.8 billion deal, and held on to $5.4 billion, a 94% share. This should have been a big story at the time. Max I was one of the largest CDOs ever underwritten, and the fact that Deutsche would have attempted to bring such a deal to market in June 2008, when everyone was feeling skittish about real estate securitizations, would have been notable in and of itself. Yet Deutsche was unable to sell off more than a tiny part of the deal. The fact that the underwriting failed should have been even bigger news. However no one paid much attention, since no public disclosure was required. Deutsche quietly offloaded its risk exposure to AIG Financial products.

Yves here. Fiderer is similarly wrong about the role this deal served for AIG. This deal appears never to have been intended to be “brought to market” and in fact was designed with AIG’s cooperation, possibly even at AIG’s instigation. These comments come in a BlackRock memo to AIG in early November on the AIG exposures:

“Deutsche is financing AIG’s position in 2a7 deals, including Project Max (which comprises the vast majority of Deutsche’s portfolio with AIG)

” AIG believes there are no early termination penalties for ending this funding facility.

“If it were not terminated, Deutsche Bank’s financing would roll off in 3 to 6 years in a staggered fashion (and AIG would fund the reference CDOs piecemeal over that period)”

“Deutsche has not been approached to unwind the facility because of the liquidit beneift that Deutsche has provided to AIG”.

This was not a typical CDO; even with the collateral calls against the MAX CDOs, AIG was still getting net liquidity from these deals. Indeed, AIG had entered into these transactions as a way to raise cash. In fact, AIG was not interested in unwinding these deals, and unlike its other CDOs, AIG had not had BlackRock, its advisor, approach its counterparties about a settlement.

While the details are opaque, it seems that these deals were designed explicitly to provide funding to AIG, and was still perceived by AIG to be on balance beneficial even the in the fact of collateral calls. Given the length of the financing facility, one can presume Deutsche never intended to sell this CDO; it’s apparently collateral for secured funding. These deals look to have had their own unique set of circumstances and do not fit in with the rest of the story. Fiderer looks to be off on wild goose chase in characterizing the MAX deals as hung transactions.

Fiderer again treats bull market greed and blindness as something more nefarious:

By the standards of any normal bond underwriting, Goldman’s inability to sell down either Altius 2 or West Coast Funding would have been viewed as a conspicuous failure. And such news would have inhibited other banks and investors, including monoline insurers, from taking on incremental CDO exposures.

Had the subprime CDO market shut down in 2006, would there have been any ripple effect on other financial markets or the real economy? It’s doubtful, since the CDOs were not financing anything new. They merely repackaged versions of mortgage bonds that had already been sold into the marketplace.

Yves here. This is inaccurate in several respects. First, finding an insurer was one of the key requirements for launching a CDO, just as finding someone to take the equity tranche. In terms of timing, the credit default swap would close on the same day as the CDO or within a few days, but the CDS was integral to getting the CDO done. And remember, the CDS was only on the top tranche, not the entire deal.

So Fiderer claims that the CDO market would have shut down had the insurers realized that the banks were retaining a lot of the insured tranches. Really? The banks were selling, not retaining the lower-rated tranches. Those investors would take losses before the AAA CDO holder and the guarantors did. Had the insurers found out the sponsors were keeping the AAA tranaches, the bankers would no doubt have protested, “Yes, we are keeping this deal because we like it.” And given how keen everyone was to keep dancing as long as the music was playing, it’s doubtful that any monoline would have questioned this sort of answer.

Second, Fiderer has this bit wrong: “They merely repackaged versions of mortgage bonds that had already been sold into the marketplace.” CDOs were essential to the subprime market. They did not “repackage bonds that had been sold.” They were the means for selling the tranches of subprime RMBS that would otherwise go unsold.

While the equity tranche of subprime bonds had a loyal following among some hedge funds (the equity tranche paid down quickly when a deal worked out according to plan, and also received the overcollateralization and excess spread), the BBB tranche was not very well loved, and the A and AA tranches were not too popular either. So CDOs were the way to sell these unwanted bits, to recombine them and make them look more appetizing through structured credit alchemy. Thus the continued growth of the subprime market depended on the ability to place CDOs. This may in part explain why investment banks like Goldman and Merrill were willing to retain the insured AAA tranches: it would keep the CDO machinery going, which was necessary to the subprime business.

There are a lot of unanswered questions, both around the Fed bailout of AIG, and the CDO market in general. And the relationships among the counterparties on the deals are worth examining; they look unusual, and some patterns suggest that banks may have been working together on particular programs. But even though the additional information released by Rep. Darrell Issa, who has led the effort to force more disclosure of the AIG bailout has been helpful, it still falls short of what is needed to understand the motives and logic of the main actors, not just the banks themselves, but the individuals involved in the resuce: Paulson, Geithner, Bernanke, and their overly-close advisor, Blankfein.

If you look at the prospectus for Adirondack 2 you will find that 67% of it was in Commercial Paper Notes – a little above $1 billion of the total deal of a little above $1.5 billion.

The other thing that is also apparent is that the Collateral Manager for Adirondack 2 was The Clinton Group. Their only other experience in CP Notes was coming from Adirondack 1.

But the Put counter party for those CP Notes was SocGen. This is, perhaps, how SocGen ended up with over $1 billion of that deal if the Put had been exercised. At some point it must have had to buy those notes from the holders.

Naturally, AIG FP was the Cash Shortfall swap party.

The prospectus for Adirondack 2 actually lists the Collateral Assets – tranches of MBS and their CUSIPs. There was only 2 percent of assets allocated to ABS (non-MBS) and only 1 percent to other CDO tranches. Around 11 percent was CMBS. The RMBS tranches were mostly credit support though as one would expect some were senior and super-senior support tranches that would generate some principal cash flow along with interest cash flow. Whether this asset mix stayed relatively static is not available to me. But I think it matters very little in terms of the default on this CDO.

I think the proximal cause lies in the CP end of things. And in the prospectus under conflict of interests you find:

CP Note Placement Agents are under no Obligation to Place CP Notes. Under the CP Note

Placement Agreement, the CP Note Placement Agents may, in their sole discretion, assist the Issuer in

placing the CP Notes. However, the CP Note Placement Agents are not obligated to do so at any time. If

the CP Note Placement Agents are unwilling or unable to place CP Notes, the Issuer will not be able to

place replacement CP Notes, and the Trustee will, on behalf of the Issuer (if the conditions to exercise

specified under “Security for the Notes—CP Put Agreement” are satisfied), exercise the CP Put Option. If

the CP Put Counterparty fails to purchase Class A-1LT-b Notes, an Event of Default will occur under the

Indenture.

Conflicts of Interest Involving the CP Put Counterparty. SG Americas Securities, L.L.C. will act as

a CP Note Placement Agent in connection with the issuance of the CP Notes, and its affiliate, Société

Générale, acting through its New York branch, will act as CP Put Counterparty and will be an investor in

the senior Notes, and may be holder of the CP Notes or other Notes. SG Americas Securities, L.L.C.’s

interests as a CP Note Placement Agent, Société Générale’s, acting through its New York branch,

interests as CP Put Counterparty, as a senior Notes investor and/or as a holder of CP Notes or other

Notes and the interests of the other Holders of Securities may, in certain circumstances, be conflicted.

It would seem likely that Socgen would have hedged their bets and likely this was a case where Goldman was the middle man in back-to-back swaps with AIG FP. Otherwise Socgen would be holding the bag on the CP Notes alone.

CDOs are not something that I understand particularly well especially on the CP end of things. However, that is my particular angle of interest here. Without being able to see the RMBS/CMBS asset mix at ML III time or even September 16 it is hard to know whether this was a garbage dump or just a Molotov cocktail just waiting for a match.

The other aspect of this deal was that the priority of payments structure allowed for principal payment on subordinate notes even while senior notes were outstanding and in normal circumstances rather than an event of default acceleration. From the prospectus:

The foregoing “shifting principal”

method permits Holders of the Class B Notes, the Class C Notes and the Class D Notes to receive

69

payments of principal in accordance with the Priority of Payments while more senior Classes of Notes and

the CP Notes remain outstanding and permits distributions of Principal Proceeds to the Holders of the

Class E Notes and the Preferred Shares, to the extent funds are available in accordance with the Priority

of Payments and the Class D Notes have been paid in full, while more senior Notes are outstanding.

Amounts properly paid pursuant to the Priority of Payments to a junior Class of Notes or to the Preferred

Shares will not be recoverable in the event of a subsequent shortfall in the amount required to pay a more

senior Class of Notes or the CP Notes.

Having amortizing credit support tranches in normal circumstances should transfer risk upstream, should it not?

Socgen, in the conflict of interests was identified as one of the Senior class A note buyers (non CP notes). But did they hold them or sell them? Selling them seems likely as my hypothesis rests on them holding the bag on the CP notes.

I suspect that The Clinton Group and likely Goldman or one or more of their affiliates were holding the subordinate tranches. But I don’t have anyway of knowing that.

So I guess the bottom line for me is – ultimately who were the parties that bought the Senior Notes (Class A)? Seemingly those parties were covered by default swaps in the back to back scenario leaving us with a very small set of visible players but no real insight as to the beneficiaries on the front side of the back to back swaps. Not knowing who those parties were doesn’t allow us to examine what the motivation was by the Fed, Treasury, et al, may have been in that context.

I have been terming the various bailouts as Operation Obfuscation and Subterfuge. The obfuscation aspect is who seemingly got paid and what seemingly were the transactions involved while the subterfuge aspect is who it was that was really being made whole.

So more debunking may be needed…

Geithner and Bernanke: Laundering money through an illegal trust ?

This afternoon on Secure Freedom Radio we announced a breaking news story concerning the Administration’s ongoing cover-up of AIG financial wrong-doing. In an interview with David Yerushalmi, senior litigator on the Murray v. Geithner et al lawsuit, we expose possible fraud, money-laundering and criminal activity.

http://biggovernment.com/fgaffney/2010/02/02/geithner-and-bernanke-laundering-money-through-an-illegal-trust/

Yves,

I stumbled across a sharp econ blog called “Macroeconomic Resiliency”. At any rate, its inaugural post explaining why the crisis was “rational”, building on the Akerlof/Romer paper, might be helpful to some of your readers, especially in understanding the role of those super-senior AAA tranches that banks so eagerly retained on their books, with or without adequate hedging:

http://www.macroresilience.com/2009/11/

I take the following as a given: The Fed and the regulatory agencies were asleep at the switch for the last 10 years as a result of Bush Administration policy, complacency, cronyism and too much insularity. The private sector took full advantage of this environment and allowed desire for short-term earnings and market share to dull the yells of competent risk managers. When the crisis hit, the government reacted with increasing panic because they had little idea of what they were dealing with. They patched together fixes on the fly in large part because they had no contingency plans. They consulted with the very people in the private sector that were both the cause and the beneficiaries of any fixes because these people were among the few that could help untangle the mess and because of aforementioned insularity and cronyism. In other words I take as established that the various players were horribly incompetent and the system that the Congress and Administration designed was horribly flawed.

Certainly some actions benefitted some companies and not others. To me one question should be whether those actions were legally improper or even if legally proper should they be changed now. Another should be whether any company, person or group of persons benefitted (or was disadvantaged) for an improper purpose (e.g. as a result of cronyism, bribery etc). The government was shovelling sacks of taxpayer money at the large, systemically important, financial institutions in a variety of ways in an effort to shore them up. That one institution (e.g. GS) benefitted should only be troubling if that benefit was disproportionate or was done for an improper purpose. All fundings should be accounted for and if any were used for purposes other than shoring up the financial institutions, then the guilty should be charged.

Oh, puuuuhlease give it a rest. Nothing changes the fact that AIG (through AIGFP) engineered the largest insurance swindle in history. End of story.

Trying to obfuscate or niggle about inconsequential details shows a definite leaning towards the Wall Street spin stories of “it just happened” or “unintended consequences” — this stuff gets really, really old.

They (JPMorgan Chase, Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley — with a bit of aid from Citi and BofA) created a global financial virus which they ultimately control and profit from. Again, end of story.

No spins, please.

Why are you setting up Fiderer as the strawman for the ‘pro-reform’ camp?

The lobbyists for the banks are virtually writing the reform legislation as it is. I would be MUCH less worried about any ‘flights of fancy’ or excessive reforms than I am about there being no effective reforms.

The greatest danger in my mind is that the banks get rules that are nice and complex, that sound good and effective on paper, but rely on regulators find the thousands of ‘wiggle room’ loopholes.

That is why I thought the Volcker rule was sound, like an external standard. You want to be a bank? Ok, do not trade for your own book. If you do, you do not get access to bank bailouts, the discount window and Treasury programs.

Wall Street HATES simplicity like that. It is hard to ‘capture.’ If one looks at the history of Glass Steagall it stood the test of time for over sixty years. Wall Street spent hundreds of millions to overturn it.

Oh, we cannot change it now because it is an anachronism, and Volcker is too old.

Oh it would not have prevented the failure of Bear and Lehman. Yes true, that was due to the subverting of the ratings agencies and credit leverage rules, which also need to be changed. But if those were fixed, if a Lehman were to go under, the issue was not with losses to Lehman’s bondholders and shareholders, but with the entanglements Lehman had as a counterpart with BANKS that were at the core of the financial system.

That is big spin that is being buried here, what Wall Street wants to hide by misdirection.

Rubbish. It is not different now.

I am not “setting up Fiderer”. I am sure you read other econoblogs, it’s hardly unusual for various bloggers to take issue with each other. He has written repeatedly on the Maiden Lane CDOs and has made various claims that are not supported. But since he provides charts and factoids, it would be easy to be persuaded if you had not dug into that topic on your own.

In this case, however, various folks in DC are looking at blogs for guidance for what went on in the crisis. And even if someone has good intentions, if they go off with unproven or erroneous charges, it makes it harder to rally resources and interest. Bloggers are already seen as borderline respectable rabble-rousers; if they can be depicted engaging in too much “fire aim ready” they can be ignored. The reason for discussing Fiderer is that AIG and the Fed are an area of active investigation

“Thus the continued growth of the subprime market depended on the ability to place CDOs.”

You said it! That insight is the key to separating the signals from the noise in this mess. The complexity of the instruments and the interconnectedness of the players is a (important, but noise) second order effect.

Before CDOs the pool of investors in RMBS would have looked elsewhere for yield and the housing bubble would never have inflated to the degree it did.

That leads me to the question, ‘who were the investors fueling the growth of these toxic instruments?’.

In late 2007, it was estimated that in Europe the largest investor class for ABS were the SIVs. In some cases they made up 80% of the AAA investor class.

That doesn’t account for all of the demand for the paper, but it’s the signal that the banks were successful and complicit in gutting existing regulations that would have limited the growth of this market. This was global regulatory capture in the extreme. The regulators were both chump and crony. The market for CDOs (and CDS) would have been limited if the backstopped investors didn’t participate.

The SIVs were implicitly (and as it turned out explicitly) guaranteed by their sponsors who in turn were backstopped by their govts. SIV CDO investors understood the implicit backstops existed. As long as the ratings agencies remained clueless (or bought), the game could continue.

This massive regulatory failure was ‘resolved’ by having the banks consolidate and bring all this paper into the explicitly backstopped umbrella, which is exactly what the SIV sponsors and senior investors and CDO sellers expected from the beginning. The junior investors weren’t so lucky.

While I greatly appreciate the time the creators of this (and other finance blogs) put into these postings, the levels of convolution involved in “Wall Street Finance” are so deep, and so non-visible, that it is impossible to really believe that anyone understands what went on, and what didn’t go on, over the past decade.

For instance, when Yves claims that “Fiderer is inaccurate” .. I am taking him at his word, but how does anyone who is not doing forensic analysis of the dead/dying AIG (for instance) really know what was going on?

It’s clear that Credit Default Swaps (or the lack of regulation requiring more-than-adequate reserves) are a real culprit here. Yet, Congress has yet to do anything about them. The main stream press does not seem to know that CDSs exist, and only a few bloggers have dealt with them in any detail.

At any rate, I am going to keep reading, and learning, but I am really distrustful of a lot of this information.

Yves,

With all due respect, I remain mystified why you never discuss Synthetic CDOs, which may represent 80% or more of the total. We still have no idea what specific products AIG insured, or what the Fed acquired in exchange for all those trillions, or whether or not these things lurking on the Fed balance sheet as Maiden Lane I, II or III (I forget which and doubt it matters) actually constitute assets in any sense to which an income stream of any kind is attached.

As for AIG, I have read suggestions that it never intended to insure this drek, that its ‘insurance’ was voided by side letters of the kind familiar to anyone who understands how reinsurance scams work. Had the records of AIG not been conveniently destroyed, perhaps we would have answers to these questions, but there must be very good reasons why our Government permits executives of AIG to extract bonuses totalling $100 million for 2009, while the company itself (and indeed the system) continues to dangle over an abyss.

Perhaps your analysis of AIG remains incomplete and cannot be cured by reading prospectuses all of which are written with a view to obscuring anything resembling truth? Without more than what you have, I would not be savaging those who keep digging.

Jake, you better duck.

Do a site search on synthetics and have a read before you continue, then do another one on the Maidens.

details, please.

None of these deals were synthetic CDOs. The only deals that had a significant synthetic component, some Goldman Abacus trades, were not part of the Maiden Lane III bailout.

Whalen has written about the use off side letters and reinsurance. I don’t recall if he claimed they were used with swaps, though. Anyone have details on this?

And what is this business about AIG records being destroyed?

Sorry, Chris Whalen of Institutional Risk Analytics. To paraphrase your typical Obamatron, “Chris Whalen is MY Treasury Secretary” — what other Whalen would we be talking about in this context?

This is David Fiderer:

I don’t think your post undercuts my argument, which is that these CDOs have the characteristics indicative of sham transactions, which, when taken together, suggest that the CDO market was largely manipulated. Quite the opposite. I have a more cynical take on your similar analysis, which was that banks retained large pieces of deals (but offloaded the credit risk) so that, as you write, “it would keep the CDO machinery going, which was necessary to the subprime business.”

I’ll start with the CDOs comprised of tranches from RMBS. You point out two important facts, which I suspected but could not back up with hard data:

1. That CDOs were necessary vehicles for placing lower rated tranches of subprime RMBS, and

2. For many banks, the purchase of a CDO and an offsetting CDS were linked, usually as contemporaneous events.

Today, we are well aware of facts that were hiding in plain sight five years ago:

a. The subprime mortgage market was riddled with fraud (liar loans were only part of it), so that

b. The data used in structuring subprime RMBS was highly suspect, so that

c. There was a strong likelihood that recovery on any tranche rated below AA (i.e. the bottom 10% of the typical capital structure) would be minimal, and

d. The fatal flaw in the capital structure of these deals would become evident shortly after the trend in rising home prices (which enabled delinquent homeowners to sell or refinance their homes) stopped, when

e. It would become obvious that the original credit ratings for lower-rated tranches subprime RMBS deals were meaningless and misleading, and

f. It would become equally obvious that the ratings for those CDOs, which were comprised of lower-rated tranches of subprime RMBS, were also meaningless and misleading.

If you had figured out the foregoing, then you had figured out that even the most senior tranches of those CDOs would prove to be worth a small fraction of par. There is an abundance of circumstantial evidence that Goldman and Deutsche had figured these dirty little secrets. If they grasped the underlying reality of these deals, then their motivations for selling these CDOs, and for passing off the credit risk on the most senior tranches to AIG and the monolines, is anything but innocent.

And if Goldman and other banks were not able to lay off the CDO credit risk on a handful of suckers, i.e. AIG and the monolines, the subprime engine would have run out of steam much earlier.

You write:

The banks were selling, not retaining the lower-rated tranches. Those investors would take losses before the AAA CDO holder and the guarantors did. Had the insurers found out the sponsors were keeping the AAA tranches, the bankers would no doubt have protested, “Yes, we are keeping this deal because we like it.” And given how keen everyone was to keep dancing as long as the music was playing, it’s doubtful that any monoline would have questioned this sort of answer.

Perhaps I’m giving too much credit to the people at monolines, but the obvious retort seems to be, “How can you say you like it if you aren’t taking the credit risk?”

Which gets back to my point about order of magnitude. You write that, “the CDS was only on the top tranche, not the entire deal.” The lower rated tranches of CDOs were tiny compared to the AAA tranches. In Adirondack-2 the AAA tranches comprised $1.4 billion out of $1.5 billion total capitalization. The AAA tranches weren’t the entire deal, but they were pretty damn close. Adirondack-2’s capitalization structure is typical.

It raises the obvious question: Why are you putting together a $1.5 billion deal? In order to sell $100 million to hedge funds, or to sell $1.4 billion in credit exposure to monolines and AIG?

I still believe that someone at the monolines with common sense would have stopped and wondered, “What’s wrong with this picture?” To analyze any structured finance transaction, you need to analyze which party is exposed to the greatest risk.

Everything still suggests that these deals looked, sounded and smelled like sham transactions. Irrational exuberance is a convenient excuse.

Which brings us to Max I, a $5.8 billion CMBS CDO, of which AIG assumed $5.4 billion of credit risk.

You cite bullet points from the BlackRock slides, which do not, in and of themselves, explain the nature of the transaction. All we know for sure is that the deal closed in June 2008, and that AIG posted $4 billion in collateral. You write:

While the details are opaque, it seems that these deals were designed explicitly to provide funding to AIG, and was still perceived by AIG to be on balance beneficial even the in the fact of collateral calls. Given the length of the financing facility, one can presume Deutsche never intended to sell this CDO; it’s apparently collateral for secured funding. These deals look to have had their own unique set of circumstances and do not fit in with the rest of the story. Fiderer looks to be off on wild goose chase in characterizing the MAX deals as hung transactions.

If these deals look to have their unique set of circumstances, what are they, exactly? And why would the NY Fed spend taxpayer money to buy them from AIGFP? Unless there’s a complete answer – not what “one can presume” or something “seems” – it’s not a wild goose chase.

David,

While CDOs were unquestionably a dubious and destructive product, you considerably overstate the case against these particular deals. Similarly, the “facts” you put forward in your post include some obvious errors. There are plenty of bad things one can correctly say about CDOs without overegging the pudding.

And ironically, although you make charges relative to these particular CDOs that you have not proven, you simultaneously understate the significance of CDOs generally.

Let’s start with your charge that these were “sham transactions.” I don’t know how you get from A to B. These were real deals with 200+ page disclosure documents. A deal could not get done unless it had an equity investor and a guarantor lined up. Those parties were independent of the issuer/packager and stood to lose money if the deal went bust. The CDO manager, another independent party, was responsible for selecting the bonds (in managed, as opposed to static, deals), took part of his fees as equity in the deal, and also had a fiduciary duty to all investors in the deal.

The type of CDOs one might characterize as “sham” were synthetic or very heavily synthetic deals. But that was not the case with the AIG deals.

Your earlier article begins with a questionable claim: “Did Societe Generale ever view its $1.2 billion investment in Adirondack 2005-2 as a buy-and-hold proposition? Or was the bank’s original intention to offload the risk on to AIG?” I address how it was not at all unusual for Eurobanks to retain the super senior tranche, a fact you seem unaware of. This was WELL KNOWN to AIG; its leaked November 2007 refers to these deals as “negative basis trades” which was the term of art for that sort of arrangement.

Now that was colossally stupid; we all know that with hindsight. And the real issue was that the monolines and AIG both vastly underpriced their insurance. But to go on the track that AIG was duped is both a stretch and unnecessary. AIG was clueless; it has come out that they didn’t even KNOW these deals were heavily exposed to subprime! They assumed, till someone bothered asking, that the ABS CDOs had only 10-20% exposure. When they realize it was much higher, they exited the business as fast as they could.

I also differed with this statement you made, and again you ignored my remarks:

Had the subprime CDO market shut down in 2006, would there have been any ripple effect on other financial markets or the real economy?

CDOs were essential to the subprime market. No ABS CDOs means no new subprime RMBS. So CDOs as a product were MORE important than you claim, and your statement again reflects a lack of knowledge (and a willingness to offer conclusions when you have no factual basis for that view).

Regarding the Deutsche Bank transaction, I made it quite clear in the post that we did not have the details to evaluate the transaction. You have shifted ground from your argument in your article, which was that this was a massive hung financing that DB had not placed. You ignored the evidence that this deal was pursuant to some sort of financing arrangement that BENEFITTED AIG. You had characterized it as the reverse, that AIG had been done a dirty by DB, and AIG had recklessly entered into a late-cycle, monster CDO.

The real question is why was this deal unwound if it was of net benefit to AIG, and AIG clearly saw it that way and wanted to keep it in place?

It is a wild goose chase to make arguments that are contradicted by presently available evidence. The Fed, which is clearly keen to keep as much as possible under wraps, can say, “Look, these critics are attacking that deal charging X. We’ve already provided information that shows X is not true. We need to put this behind us, there isn’t any point in answering these critics, particularly when the don’t bother digesting the extensive information we’ve been required to make available.”

The Fed, which is clearly keen to keep as much as possible under wraps, can say, “Look, these critics are attacking that deal charging X. We’ve already provided information that shows X is not true. We need to put this behind us, there isn’t any point in answering these critics, particularly when the don’t bother digesting the extensive information we’ve been required to make available.”

—————————–

Yes! That’s exactly what they will do, and have done. We saw Geithner do it the other day.

If you’d check the link I offered above, it gives a strong sense of not only why super-senior AAA tranches retained by banks were an essential part of the CDO manufacturing process, but also how such low bps returns, which were unsaleable, were uniquely suited to being carried on the banks books, given they could be “financed” with the cheapest possible leverage, as offset by the lowest possible regulatory capital charges, even if not further hedged, and thus could be surprisingly profitable on an ROE basis only to the originating bank or a similar “institution”. The accumulation of super-senior AAAs was rationalized as an effect of “servicing” CDO clients, but the seeming profitability of their “negative basis trade” made it highly attractive to senior management from a regulatory capital POV, such that, in the case of UBS, at least, as cited from the retrospective shareholders’ report, the inadequate hedging of such tranches, which the author attributes to the CDO desk simply deceiving senior management about the risk, just as AIG would be deceived about the risk, raised no alarms. All this in an explanatory context wherein the whole CDO market is analysed as a looting/ponzi scheme. Principal/agent and asymmetric information problems so riddled the whole process, that distinguishing between willful corruption and willful blindness becomes a moot point.

Your link to ‘A “Rational” Explanation of the Financial Crisis’ methodically distills what many readers here (and many econ-challenged taxpayers) already intuit correctly—that a complete lack of regulation and suspension of moral hazard has led to ‘rational’ exhuberance by the investor class at the expense of producer chumps. It’s time for aggressive investigations and hard time; market capitalism will not survive another painless ‘fix’.

Yves,

The question of why no one looked to AIG after Bear (if not before) is so crucial. Glad you pointed it out.

If Neel Kashkari and Philip Swagel(sp?) are to be believed, Treasury “knew” by Jan. 2008 that they were going to need a big bailout (i.e. TARP), but knew they couldn’t get approval without real fear in the air.

What the heck were they doing between that time and September?!

Yves,

This is an impressive post. It is a great example of what a serious blog should be.

The preamble alone is worthy of a separate post. It was reassuring to hear you explain your goals so clearly. I’ve been a little puzzled lately about where you were heading.

Fiderer’s post begged for scrutiny and analysis and he got it.

Fiderer’s comment defending his post was also valuable to me.

Taken together the entire package advances my understanding of this fascinating and complicated story. Well done.

I feel silly writing a fan note, so I’m going undercover, but since I think blogs are invaluable and good blogs are rare you deserve some kudos.

Yves,

“And where was the Fed? CDS were a known systemic risk as of the Bear rescue; any reasonable look at that market would have led straight to AIG. The “we weren’t their regulator” excuse is spurious; they regulated AIG’s counterparties and could easily have connected the dots, particularly since the monolines were on the ropes as of early 2008”

It’s worse than that. Your timeline’s off by about a year.

It was clear the monolines were on the ropes in early 2007 not early 2008. LSS conduits, which were the synthetic version of monoline insurance were imploding in 2007, culminating with the collapse of the Canadian CP market in August 2007. There wasn’t a bank, regulator, insurance company or institutional investor on the planet who wasn’t accutely aware of its potential impact on the monolines and AIG by mid 2007.

The real question isn’t where was the Fed in the time between Bear’s collapse and Sept, but where was the Fed’s head from early 2007 till September 2008. There was more than enough time to anticipate and develop a plan.

One could argue that Paulson’s SIV plan that never got off the ground was the intended answer (that they saw there was a problem, and set out in a way that could never have succeeded, to address the biggest, most immediate manifestation).

In other words, the Fed and Treasury were just treating symptoms as they arose, no intent to deal with root causes. And I don’t see any evidence of any investigation. Paulson seemed to be the sort of guy who believed he could learn what he needed to by making phone calls; the Fed was a near-religious believer in the proliferation of the virtue of derivatives.

Not sayin’ you aren’t correct, but there is surprisingly little evidence of the Fed or Treasury taking this issue seriously. In fact, the press account of Dinallo trying to cobble together a rescue for the monolines suggested that the NY Fed was prodding a little, but not doing much to support a deal.

Now rescuing the insurers might not have been the best answer, but I don’t see any evidence of serious study of the problem.

Just a bit of google wanderlust came up with this:

http://ftalphaville.ft.com/blog/2008/05/23/13299/friday-epic-last-of-the-romans/

The clincher: “Citigroup Inc. created a $2.5 billion mortgage-backed security called Bonifacius Ltd. in August as capital markets seized up and panic swept Wall Street.

The issue took the name of a general, called by historian Edward Gibbon the “last of the Romans,” who fought and died for a fading empire. The bonds were created from subprime home loans as demand evaporated. Within six months, Bonifacius collapsed as homeowners fell behind on their payments in record numbers.

There are surely more etymylogical ironies out there when it comes to CDOs. Bonifacius means “good fate”, which is a prediction the investors in that particular CDO might take umbrage at.”

Now the question is whether such tell-tale “literary” signs, which doesn’t require a degree in deconstructionism to detect, could “count” as legal evidence of intention or disposition.

Gordian comes to mind. The first SIV.

From the standpoint of what Fedtreasury *should* have been doing, yes, we must look at the period leading up to Bear’s ultimate implosion, but according to Kashkari, they (quote) “knew” by the beginning of 2008 that they would need a bailout — presumably because the Super SIV wasn’t happening. Just based on public statements Bernanke and Paulson made, vs. what they “knew” in private, there should be some investigation into what they knew and when they knew it. At this point we can only speculate as to whether the various actors (Paulson, Bubbles, Geithner…) were simply incompetent/negligent or whether they were deliberately deceptive — for whatever reasons.

Just the fact that Treasury wanted a bailout, but hid this fact from Congress until such time as they could sufficiently scare them is troubling. It should be troubling to Congress, but they don’t seem to care that they’ve been duped. Or maybe they just don’t want it talked about.