By Rob Parenteau, CFA, sole proprietor of MacroStrategy Edge, editor of The Richebacher Letter, and a research associate of The Levy Economics Institute

The question of fiscal sustainability looms large at the moment – not just in the peripheral nations of the eurozone, but also in the UK, the US, and Japan. More restrictive fiscal paths are being proposed in order to avoid rapidly rising government debt to GDP ratios, and the financing challenges that may entail, including the possibility of default for nations without sovereign currencies.

However, most of the analysis and negotiation regarding the appropriate fiscal trajectory from here is occurring in something of a vacuum. The financial balance approach reveals that this way of proceeding may introduce new instabilities. Intended changes to the financial balance of one sector can only be accomplished if the remaining sectors also adjust. Pursuing fiscal sustainability along currently proposed lines is likely to increase the odds of destabilizing the private sectors in the eurozone and elsewhere – unless an offsetting increase in current account balances can be accomplished in tandem.

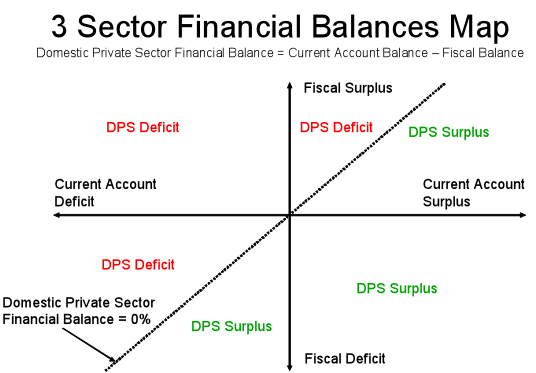

To make the interconnectedness of sector financial balances clearer, proposed fiscal trajectories need to be considered in the context of what we call the financial balances map. Only then can tradeoffs between fiscal sustainability efforts and the issue of financial stability for the economy as a whole be made visible. Absent consideration of the interrelated nature of sector financial balances, unnecessarily damaging choices may soon be made to the detriment of citizens and firms in many nations.

Navigating the Financial Balances Map

For the economy as a whole, in any accounting period, total income must equal total expenditures. There are, after all, two sides to every transaction: a spender of money and a receiver of money income. Similarly, total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible capital during any accounting period.

For individual sectors of the economy, these equalities need not hold. The financial balance of any one sector can be in surplus, in balance, or in deficit. The only requirement is, regardless of how many sectors we choose to divide the whole economy into, the sum of the sectoral financial balances must equal zero.

For example, if we divide the economy into three sectors – the domestic private (households and firms), government, and foreign sectors, the following identity must hold true:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance + Foreign Financial Balance = 0

Note that it is impossible for all three sectors to net save – that is, to run a financial surplus – at the same time. All three sectors could run a financial balance, but they cannot all accomplish a financial surplus and accumulate financial assets at the same time – some sector has to be issuing liabilities.

Since foreigners earn a surplus by selling more exports to their trading partners than they buy in imports, the last term can be replaced by the inverse of the trade or current account balance. This reveals the cunning core of the Asian neo-mercantilist strategy. If a current account surplus can be sustained, then both the private sector and the government can maintain a financial surplus as well. Domestic debt burdens, be they public or private, need not build up over time on household, business, or government balance sheets.

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance + Fiscal Balance – Current Account Balance = 0

Again, keep in mind this is an accounting identity, not a theory. If it is wrong, then five centuries of double entry book keeping must also be wrong. To make these relationships between sectors even clearer, we can visually represent this accounting identity in the following financial balances map as displayed below.

On the vertical axis we track the fiscal balance, and on the horizontal axis we track the current account balance. If we rearrange the financial balance identity as follows, we can also introduce the domestic private sector financial balance to the map:

Domestic Private Sector Financial Balance = Current Account Balance – Fiscal Balance

That means at every point on this map where the current account balance is equal to the fiscal balance, we know the domestic private sector financial balance must equal zero. In other words, the income of households and businesses just matches their expenditures (or alternatively, if you prefer, the saving out of income flows by the domestic private sector just matches the investment expenditures of the sector). The dotted line that passes through the origin at a 45 degree angle marks off the range of possible combinations where the domestic private sector is neither net issuing financial liabilities to other sectors, nor is it net accumulating financial assets from other sectors.

Once we mark this range of combinations where the domestic private sector is in financial balance, we also have determined two distinct zones in the financial balance map. To the left of the dotted line, the current account balance is less than the fiscal balance: the domestic private sector is deficit spending. To the right of the dotted line, the current account balance is greater than the fiscal balance, and the domestic private sector is running a financial surplus or net saving position.

This follows from the recognition that a current account surplus presents a net inflow to the domestic private sector (as export income for the domestic private sector exceeds their import spending), while a fiscal surplus presents a net outflow for the domestic private sector (as tax payments by the private sector exceed the government spending they receive).

Accordingly, the further we move up and to the left of the origin (toward the northwest corner of the map), the larger the deficit spending of households and firms as a share of GDP, and the faster the domestic private sector is either increasing its debt to income ratio, or reducing its net worth to income ratio (absent an asset bubble). Moving to the southeast corner from the origin takes us into larger domestic private surpluses.

The financial balance map forces us to recognize that changes in one sector’s financial balance cannot be viewed in isolation, as is the current fashion. If a nation wishes to run a persistent fiscal surplus and thereby pay down government debt, it needs to run an even larger trade surplus, or else the domestic private sector will be left stuck in a persistent deficit spending mode.

When sustained over time, this negative cash flow position for the domestic private sector will eventually increase the financial fragility of the economy, if not insure the proliferation of household and business bankruptcies. Mimicking the military planner logic of “we must bomb the village in order to save the village”, the blind pursuit of fiscal sustainability may simply induce more financial instability in the private sector.

Leading the PIIGS to an (as yet) Unrecognized Slaughter

The rules of the eurozone are designed to reduce the room for policy maneuver of any one member country, and thereby force private markets to act as the primary adjustment mechanism. Each country is subject to a single monetary policy set by the European Central Bank (ECB). One policy rate must fit the needs of all the member nations in the Eurozone. Each country has relinquished its own currency in favor of the euro. One exchange rate must fit the needs of all member nations in the Eurozone. The fiscal balance of member countries is also, under the provisions of the Stability and Growth Path, supposed to be limited to a deficit of 3% of GDP. The principle here is one of stabilizing or reducing government debt to GDP ratios. Assuming economies in the Eurozone have the potential to grow at 3% of GDP in nominal terms, only fiscal deficits greater than 3% of GDP will increase the public debt ratio.

In other words, to join the European Monetary Union, nations have substantially diluted their policy autonomy. Markets mechanisms must achieve the necessary adjustments – policy measures cannot. Policy responses are constrained by design, and experience suggests relative price adjustments in the marketplace have a difficult time at best of automatically inducing private investment levels consistent with desired private saving at a level of full employment income.

Now let’s layer on top of this structure three complicating developments of late. First, current account balances in a number of the peripheral nations have fallen, in part due to the prior strength in the euro. Second, fiscal shenanigans along with a very sharp global recession have led to very large fiscal deficits in a number of peripheral nations. Third, following the Dubai World debt restructuring, global investors have become increasingly alarmed about the sustainability of fiscal trajectories, and there is mounting pressure for governments to commit to tangible plans to reduce fiscal deficits over the next three years, with Ireland and Greece facing the first wave of demands for fiscal retrenchment.

We can apply the financial balances approach to make the current predicament plain. If, for example, Spain is expected to reduce it’s fiscal deficit from roughly 10% of GDP to 3% of GDP in three years time, then the foreign and private domestic sectors must be together willing and able to reduce their financial balances by 7% of GDP. Spain is estimated to be running a 4.5% of GDP current account deficit this year. If Spain cannot improve its current account balance (because remember, it relinquished its control over its nominal exchange rate the day it joined EMU), the arithmetic of sector financial balances is clear. Spain’s households and businesses will need to spend 7% of GDP more than they earn over the duration of the next three years, thereby adding more private debt to their balance sheets.

Spain already is running one of the higher private debt to GDP ratios in the region. In addition, Spain had one of the more dramatic housing busts in the region, which Spanish banks are still trying to dig themselves out from (mostly, it is alleged, by issuing new loans to keep the prior bad loans serviced, in what appears to be a Ponzi scheme fashion). It is highly unlikely Spanish businesses and households will voluntarily raise their indebtedness in an environment of 20% plus unemployment rates, combined with the prospect of rising tax rates and reduced government expenditures as fiscal retrenchment is pursued.

Alternatively, if we assume Spain’s private sector will attempt to preserve its estimated 5.5% of GDP financial balance, or perhaps even attempt to run a larger net saving or surplus position so it can reduce its private debt faster, Spain’s trade balance will need to improve by more than 7% of GDP over the next three years. Barring a major surge in tradable goods demand in the rest of the world, or a rogue wave of rapid product innovation from Spanish entrepreneurs, there is only one way for Spain to accomplish such a significant reversal in its current account balance.

Prices and wages in Spain’s tradable goods sector will need to fall precipitously, and labor productivity will have to surge dramatically, in order to create a large enough real depreciation for Spain that its tradable products gain market share (at, we should mention, the expense of the rest of the Eurozone members). Arguably, the slack resulting from the fiscal retrenchment is just what the doctor might order to raise the odds of accomplishing such a large wage and price deflation in Spain. But how, we must wonder, will Spain’s private debt continue to be serviced during the transition as Spanish household wages and business revenues are falling under higher taxes or lower government spending?

Nice graph and analysis and all that, but I can’t help wondering whether there aren’t a lot of people in Germany looking for an opportunity to buy a nice little (or not so little) apartment or villa with sea views in sunny Spain or Greece, and thinking that a little deflation in those places would create some good-looking opportunities. Especially if wages for the hired help came down too.

Too many Germans already have a property in Spain…

That was actually (together with all the demand from all the other Northern European countries) one of the reasons for the construction boom in Spain so far.

Agreed. While you are correct, Gordon, that forced asset sales by Spaniards could be one result of fiscal retrenchment undermining private debt servicing (along with cheap domestic labor resulting from both), you might need a gated community too, and who knows what will be floating in your sangria.

An interesting corrolary to the Asian mercantilists is that if you run current account deficit, both your private and govt sector can run deficits too! (which is exactly what was happening).

Yes, vlade, that is the upper half (above the dotted line that is) of the southwest quadrant. Remember, a current account deficit is foreign net saving (they are earning more by selling to us than they are buying from us), so that is the counterpart to one nation’s deficit spending on both the government and domestic private sides.

The US is now in the lower half (below the dotted line) of the southwest quadrant, as is Spain and much of the periphery,as the GFB is less than the CUB, and both are negative. More on that tomorrow.

The analysis is a bit lame

First:

“Assuming economies in the Eurozone have the potential to grow at 3% of GDP in nominal terms, only fiscal deficits greater than 3% of GDP will increase the public debt ratio.”

This statement is simply and planely false. If you consistently run 3% deficits and your economy grows by 3% per year, the public debt to GDP ration is going asypmtotically against 100%. So if you start with less than 100% debt to GDP ratio, this ratio will increase in that scenario, if you start with more debt, the ratio will go down.

Second

“Spain’s households and businesses will need to spend 7% of GDP more than they earn over the duration of the next three years, thereby adding more private debt to their balance sheets.”

This statement is again not true. True is, the private sector in Spain has to reduce its net saving by 7% of GDP. Given, that the private sector currently runs a surplus – proven by the numbers in the text and the accounting identity – the fiscal deficit is currently higher than the current account deficit – this would not mean, that the private sector must spend 7% more than it earns. This would be only true, if the current savings rate would be zero.

As well the second part of the statement is misleading, despite not being false. The private sector will add debt, but of course this is not an accounting necessity, as many people will read into that statement. Actually the private sector could use savings to pay for the increased consumption. This of course can be influenced by the gov’t. Increasing taxes for high income earners with high savings rates, wealth taxes etc. would actually REDUCE the overall balance sheet of the economy by netting out positions.

Another issue is, that Spain can reduce its current account deficit by reducing demand/imports. This doesn’t require a surge in exports, a reduction in income or a surge in productivity. Competitiveness is NOT the same as running CA surpluses.

From somebody, who is a earning his money as an economist, I would expect a little bit more accuracy.

I agree: it’s lame.

Third

Spanish unit labour costs’ gap with Germany’s has been reduced by half in just two recession years. The author seemingly ignored this, or considered it unworthy of an article focusing precisely on Spanish competitiveness.

Fourth

A simple, unmentioned way to improve the current-account balance is increasing taxes for imports while lowering taxes for domestic production, i.e. increasing VAT while lowering other taxes. Which is exactly what is happening right now in Spain.

Again, the author ignored this or maybe thought it would ruin his article.

As difficult as these adjustments may be for Spain and many of her citizens, the positive impact of converging with the strongest countries productivity measures has to have long-term positive impact on potential Spanish prosperity. Good luck to all of Spain (and Greece and every other country) as they go through these very stressful times.

Eric –

Yes, let’s hope people have the wisdom to understand the trade offs involved, and the will to make their choices known and to enact them.

Right now, people are being steamrolled into an arbitrary definition of fiscal sustainability without being shown the full range of their choices, or the full ramifications of the current course of actions.

Regarding productivity improvement (or even convergence with Germany) in the peripheral nations, remember this largely remains a zero sum game within the eurozone (known as beggar thy neighbor) unless more global demand for eurozone produced tradable goods can be generated as well.

Or to put it slightly differently, the whole world cannot achieve export led growth, especially if the US consumer is no longer the global spender of first and last resort.

Diego:

Please help me understand the basis for your statement on

Spain closing so much of its labor cost gap with Germany. In light of the following, and the ECB results I provide in a response earlier today, I cannot confirm your assertion. Maybe you could be more specific about how you are defining the gap (over what time period).

The following appears as part of a larger piece on internal devaluation here at Alpha Sources. As an aside, I think the author is not getting the risk of destabilizing private debt by pursuing policy paths involving domestic private income deflation. This is the problem with an internal devaluation approach that does not take into account the financial balance equation:

http://clausvistesen.squarespace.com/alphasources-blog/2009/12/28/quantifying-eurozone-imbalances-and-the-internal-devaluation.html

“both Greece and Spain have seen their labour cost surge relative to Germany since the inception of the Eurozone. Since Q1-00 the accumulated change in the German index has consequently been 15.2% which compares to 97.7% and 105.6% for Greece and Spain respectively.

More demonstratively however is the fact that since the second half of 2006 the labour cost index of Spain and Greece have been above the Germany relative to 2005 which is the base year. Consider consequently that the labour cost index in Greece and Spain was 13.3% and 16.4% below the German ditto in Q1-2000 and now (even with the recent surge in German labour costs), the Greek and Spanish labour cost index stands 7.2% and 5.2% above the German index.”

Martin:

The statement is NOT false.

A simple spreadsheet will demonstrate that, regardless of Debt : GDP ratio, if deficit growth equals GDP growth, then there is no increase in Debt : GDP ratio. The one exception where this is not the case is if the initial deficit is greater that the initial total debt, which is an extreme condition.

Where deficit growth = GDP growth: 1) if the initial deficit is equal to the initial debt, the debt : GDP ratio stays the same, 2) if it is less, then the ratio decreases, 3) only if the initial deficit exceeds the debt does the ratio increase.

This holds even when initial debt is larger than initial GDP (Note that the deficit is assumed to include debt interest).

Assume the starting debt is 10% of GDP. The deficit is 3%, the GDP growth is 3%.

Next year GDP is 103, debt is 13.

13/103 > 10/100

That is the situation described in the text. It is not clear, what your comment means. “Deficit growth” is certainly irrelevant for the case study, unless you mean “debt growth”. But then you would speak of a different situation than the one described in the text – and your claim would still be partially wrong.

Deficit = Mismatch of revenue and spending in a given year

Debt = Total amount of money owed by the gov’t

pebird – see response to Martin further on. Hopefully it clarifies any confusion on this matter. If not, come back with your concerns.

Martin,

The private sector may well use increased savings to fund consumption, but that is an ex post activity, which has nothing to do with the recognition that private savings is the accounting correlative to a savings deficit elsewhere. And furthermore, that private consumption (in contrast to government spending) has an inherent external constraint.Private saving, however accomplished, increases the future consumption possibilities for the household sector at the expense of current consumption. Saving is foregone consumption which in normal times (barring huge financial crashes) will enhance future consumption.

In this context, because the household sector is revenue-constrained, it has to sacrifice consumption possibilities now to improve them later. It can increase consumption now beyond income via increasing its indebtedness or selling assets (past saving) but the budget constraint has to be obeyed at all times.

But, of-course, this sort of reasoning doesn’t apply to the government. A budget surplus does not create a cache of money that can be spent later. Government spends by crediting a reserve account. That balance doesn’t “come from anywhere”, as, for example, gold coins would have had to come from somewhere. It is accounted for but that is a different issue.

Even neo-classical economists such as Greg Mankiw recognise that “the rules of national income accounting include several important identities. Recall that an identity is an equation that must be true because of the way the variables in the equation are defined.” To say that this observation is “lame” or “misleading” is to argue that the statement “2+2=4” is misleading.

Ultimately, without a budget deficit the non-government sector cannot save net financial assets in the currency of issue. That again is simple double entry bookkeeping, not high Keynesian theory or an apologia for “Big Government”.

I have not argued against the accounting identity, but against the assumption, that for reducing the public deficit, the private sector would have to run deficits.

Let’s assume for a moment there is no external sector. In this case, USING the accounting identity, the public deficit HAS to be financed from private savings. Now, if the gov’t wants to reduce its deficit, that doesn’t mean, that the public sector has to run a deficit, but just a reduction in the savings rate has to occur, equaling the deficit reduction in the public sector.

The fiscal deficit in Spain currently is bigger than the current account deficit. So at least to some degree, we are in the situation, that Spaniards save privately and lend their private money to the gov’t. So if the gov’t reduces its deficit, the people could just spend the money, they would have otherwise lend to the gov’t.

As we are in liquidity trap land, this actually might not happen. However, my point is, that the gov’t can to some degree take the money via taxation instead of borrowing it. Now is a good time to increase the taxes on the income of rich people.

I’m not sure, why this would be an argument against “big gouvernment”. Especially as this is a US-American web site. The Republicans are for sure more in favour of deficits than on increasing taxes on their “base” of rich people.

I don’t know the exact situation in Spain. But I would guess, there is some room for tax increases on people making 100+k Euro per year.

Martin, you are correct. You can have a situation where the government runs a balanced budget and the external sector runs a huge surplus. In this situation, the surplus does not undermine economic growth because the injections into the spending stream are exactly offset by the leakages in the form of the private saving and the budget surplus. Norway does that, as one example. But it’s an impossibility for every country in the world to run trade surpluses.

That’s the only situation where scenario works. In a situation in which the private domestic sector wants to net save and they translate this intention into action by cutting back consumption (and perhaps investment) spending.

The falling income would not only reduce the capacity of the private sector to save but would also push the budget balance towards deficit via the automatic stabilisers. It would also push the external surplus up as imports fell. Eventually the income adjustments would restore the balances but with lower GDP overall.

But in a situation in which the government sector accommodates that rising desire of the private sector to save by the private sector by running a deficit, then the economy can continue to grow.

Rob’s point is that if the drain on spending outweighs the injections into the spending stream then GDP falls (or growth is reduced). No way of getting round that.

Martin –

Here is where you may be getting tripped up.

“So if the gov’t reduces its deficit, the people could just spend the money, they would have otherwise lend to the gov’t”

You are implicitly assuming private sector saving is unchanged, regardless of the fiscal balance.

If the government raises taxes and reduces expenditures to reduce the fiscal deficit, then the domestic private sector

will, in any accounting period, have a lower financial balance. The only way to get around that if for the current account balance improves in an offsetting fashion.

On what basis do you believe a change in the fiscal balance will always and everywhere be matched by an equal change in the current account balance?

Look at the piece again.

DPSFB = CUB – GFB

You are implicitly assuming an increase in GFB will be offset by an equal increase in CUB, so there is no change in DPSFB.

That is what you are saying by “just let the people spend the money they otherwise would have lent the government”.

You appear to be missing the interelated character of sector financial balances. Ask yourself, how does the domestic private sector achieve a cash flow in its favor in order to achieve a net saving position (or financial surplus)?

As the article indicates, there two ways:

The government sector spends more money than it takes in for taxes.

Foreigners buy more tradable products than they sell to a nation.

I don’t understand this simple accounting identity. If the government can print money (by selling bonds to the Fed) then the amount of money is not conserved, and doesn’t the equation fail? Of if the Fed buys commercial paper, or buys mortgages, (without selling bonds into the market), then again doesn’t the equation fail? Could someone please explain this identity to me in a simpler fashion?

Actually none of the PIIGS can print money, that’s the problem. Without the ability to change the monetary picture it becomes an accounting game.

Banks in the eurozone can create money when they make loans or buy securities. They credit a deposit of equal amount, and bank deposits are money (as a means of final settlement, and convertible at par into currency).

Banks in the eurozone can buy government debt issues. Banks can also repo government securities to the ECB.

So perhaps there are indirect routes to creating money that have been discovered by eurozone nations. Greece and Ireland in particular seem to have figured this loophole out.

best,

Rob

steveb –

We are starting from the equality of money spent on final goods and services (total expenditures) = money received (total income).

If the government can instruct the Fed to credit private bank accounts as it spends money on goods and services produced by the private sector, then we have income earned by private sector equal to government expenditures.

How money is created and destroyed in the system does not influence the identity between total income and expenditures.

If the Fed buys existing assets from the private sector, all it is doing is changing the composition of assets already held on private sector balance sheet.

If the domestic private sector as a whole wants to deficit spend – that is, spend more money on final goods and services than it earns from producing final goods and services – it can choose to reduce its net worth and net financial asset position by using the cash it received from selling assets to the Fed in order to buy imports, for example. Then, both DPSFB and CUB fall.

Does that help? Remember, money is an outstanding stock at any point in time. Money creation (central and commercial bank balance sheet expansion) and destruction (tax and bank loan repayment) changes the stock of outstanding money. The financial balance approach examines flows of money on final goods and services during an accounting period.

To put things in perspective: “Krona’s Anti-Euro Appeal Makes Sweden the Best Bet (Update2)”

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=a5eTmhZT_68M&pos=7#

Swedish Lex –

Right, Sweden is operating in the southeast corner of the finacial balances map. With a 7% of GDP current account surplus, and a 3.3% of GDP fiscal deficit, it is running a 10.3% of GDP financial surplus in its domestic private sector.

That is to say, Swedish households and businesses are saving more than 10% of GDP out of income flows than they are spending on tangible investment (capital equipment and housing). The Swedish DPS can pay down debt or accumulate financial assets.

Main issue here would be if krona appreciates so much on flight from euro that the trade surplus deteriorates. If the domestic private sector insists on maintaining such a large finacial surplus, fiscal deficit will have to widen, or else nominal income will decline. More likely, if they have a housing boom developing, desired private net saving rate will fall, as is typical when asset prices are appreciating more than normal.

Martin –

The Maastricht Accord stipulates 3% of GDP fiscal deficit limits, with the objective of stabilizing public debt to GDP ratios of 60%.

This works if nominal GDP is 5% and you start with a 60% public debt to GDP ratio. The sentence you point out should “read potential to grow at 3% in real terms”, which assuming inflation is held to 2%, gets you to 5% nominal.

The mathematical principle is simple: the ratio of 1) the fiscal deficit to nominal GDP to 2) the nominal GDP growth rate must equal the ratio of public debt to nominal GDP that is being targeted.

So under Maastricht, assuming a 3% fiscal deficit limit, and nominal GDP growth near 5% (since ECB is supposedly targeting “price stability” of 2% inflation), you can stabilize a 60% public debt to GDP ratio (.03/.05 = .6 or 60%). The principle is the incremental or marginal rate has to equal the average ratio, and you must recognize the deficit is the increment to public debt. Given the short attention span theater of the blogosphere, I chose not to spell this out.

My apologies for mistyping nominal when I meant real, which is how potential GDP growth is typically measured. That was truly lame on may part.

Actually, what may also be truly lame is the notion that any arbitrary public debt to GDP ratio, let’s just say 60%, is the correct one which should be sustained into eternity, under all conditions.

If you want to dig deeper into debt stability conditions, I encourage readers to get Luigi Pasinetti’s “The myth (or folly) of the 3% deficit-GDP Maastricht parameter” in one of the 1998 issues of the Cambridge Journal of Economics. Over a decade ago, Pasinetti depicted some of the flaws in thinking about fiscal sustainability, and these flaw are only now getting exposed and recognized.

I also have applied debt trap equations to the private sector, which for mostly ideological reasons as far as I can tell, appears to be rarely done. It helped me identify the last asset bubble and get my clients out of the way of the bust. You can find the analysis at the following link.

http://www.levy.org/vdoc.aspx?docid=866

On your second point, I think there may be something garbled. In the first case, I assume all of the adjustment burden falls on the domestic private sector. If the fiscal balance increases from a -10% of GDP deficit to a -3% level, then the 5.5% financial surplus of the domestic private sector has to fall to a -1.5% of GDP deficit. So yes, this deserves to be made clear. A 7% increase in the fiscal balance requires an offsetting 7% decrease in the DPSFB, relative to their prior levels, again assuming no change in the current account balance.

You are also correct that a sector running a financing deficit has at least three options. It can increase debt by issuing liabilities. It can run down existing cash assets. Or it can sell less liquid asset holdings to other sectors (here, that would mean the DPS selling assets to the government or foreigners).

Each of these responses will reduce the net worth or net financial assets held by the DPS, barring asset price appreciation in their existing holdings. Lower net worth means a lower margin of safety, a lower equity cushion, and a more leveraged DPS…that is, higher odds of financial instability.

If the government raises taxes on high saving households, that would have the effect of reducing the DPS financial balance and increasing the government financial balance. Financial balances are flows over time. They accumulate as stocks of assets and liabilities on balance sheets at any point in time. A sector running financial surpluses is usually accumulating assets and improving net worth (absent adverse changes in prices of existing asset holdings), so you will have to be clearer about which balance sheets you are proposing to consolidate with regard to your “shrinking balance sheet, netted out positions” conclusion.

Spain can reduce its current account by reducing imports. That requires domestic producers delivering goods and services that offer better value than similar imports. That has to do with relative prices and substitution of domestic for imported goods. Or domestic private incomes can be lowered, reducing demand overall, including import demand. Then relative income growth effects the trade balance. The latter tends to dominate the former, but not always.

Since Spain cannot influence its nominal exchange rate, not sure how you propose reducing Spanish imports beyond these two channels of lower domestic prices (which mean lower profit margins, lower wage rates, higher labor productivity, or some combination thereof) or lower domestic income growth, unless it involves a faster pace of product innovation.

Hope that helps,

Rob

Yes, that helps. Sorry if I was harsh on you, but there are actually as well a lot of people around, who really don’t get the basic principles. After all in a democracy everybody has a stake in the public finances.

Martin –

Apology accepted. I appreciate your close reading of the material and there were indeed things that needed to be clarified which I am glad you were able to surface.

And yes, I entirely agree the basic principles need to be exposed, discussed, and understood by investors, policy makers, economists, and most of all citizens whose lives will surely be influenced by these decisions.

At the moment, it is just a huge muddle laced with lots of ideological skirmishes and little real progress.

Martin, good work catching that.

Another beef of mine is the way they report percentage changes. You never know if they are talking about month to month, quarter to quarter or year to year.

Diego –

Patience. Part II mentions the tax switching option, although I suspect the EC does not look favorably upon tariffs, taxes on imports, and the like, so this must take the form of raising VAT while reducing other taxes, in particular those related to employment.

Regarding your claim that:

“Spanish unit labour costs’ gap with Germany’s has been reduced by half in just two recession years. The author seemingly ignored this, or considered it unworthy of an article focusing precisely on Spanish competitiveness.”

Please do share your sources, as the ECB stats show Spain’s unit labor costs have gone flat since 2008 Q3, while Germany’s are up 4.4%.

http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=119.ESA.Q.ES.Y.1000.UNLACO.0000.TTTT.D.N.I

http://sdw.ecb.europa.eu/quickview.do?SERIES_KEY=119.ESA.Q.DE.S.1000.UNLACO.0000.TTTT.D.N.I

Also, take another look. The article is not all about Spain or Spain’s competitiveness. It is about working with a stock/flow consistent macroeconomics. The point of the article is that shifts in fiscal balances will impact the financial balances of other sectors. Fiscal retrenchment may undermine the ability of the private sector to service its existing debt. If Spain shoots for a 3% of GDP fiscal deficit in 3 years, and Spain’s domestic private sector continues to attempt to net save near its current 5.5% of GDP, then Spain’s current account balance needs to swing from -4% of GDP to +2.5% of GDP…otherwise, nominal income levels will fall, and private debt distress will escalate, and Spain will be on Irving Fisher’s debt deflation path.

best,

Rob

If the euro is to be viable, Europe needs either a unified budget or a debt union. Now the reason it doesn’t have either of these is because of the political obstacles to them. The result is persistence in an unsustainable policy. This never ends well.

Yes, the politics were always problematic. There is a design flaw in the EMU, which will be discussed further in Part II tomorrow.

There were people who understood this over a decade ago. I would direct you to Jan Kregel’s 1999 article in the Eastern Economic Journal entitled “Currency Stabilization through Full Employment”, and subtitled “Can EMU Combine Price Stability with Employment and Income Growth?”. PP. 38-9 accurately depict one of the central design flaws, and his solution follows in the remaining pages.

But now it looks like we will get piecemeal fiscal “unification”, with IMF style conditionality, and perhaps more than a passing flirtation with debt deflation.

Isn’t what the article describes, called ‘internal devaluation’? I think it applies to any country that has seen a rapid rise in household debt, between 1990-2009.

Internal devaluation, as I understand it, refers to policy measures that reduce labor costs and so can improve the price of a country’s tradable products relative to its competitors, without any change in its nominal exchange rate.

Reduction of labor costs can involve tax switching, which I will briefly discuss in part II. As I mentioned in the response to Diego, a government could cut taxes that are used to fund social security benefits, which affect employment costs, and raise VAT taxes on domestic consumption goods.

Cavallo has proposed something along these lines for Greece (he calls it a fiscal devaluation), but I honestly do not know whether it could fly politically, since VAT taxes are regressive, and 2/3rds of the social security tax is paid for by businesses. Might be a hard sell for a socialist government…although I have seen stranger things happen.

The article is not really about internal or fiscal devaluations, however, nor it about Spain’s competitiveness, as mentioned in the reply to Diego. It is about how fiscal policy cannot be considered in isolation of the other sector financial balances, and so fiscal sustainability cannot be defined without regard to the larger issue of financial stability for the economy as a whole – which includes the capacity of the private sector to handle its debt load as well. Fiscal devaluations may offer one way to deal with some of the trade offs that only become visible once one comprehends the financial balance approach and embraces a stock/flow coherent macroeconomics.

Why can not the amount of imports fall dramatically

r cohn –

The question, is how are you going to get imports to fall?

If the answer is by using fiscal austerity to drive nominal private incomes down, which will in turn drive private spending down, including spending on imports, then you have to ask yourself what happens to the capacity of the private sector to service its existing debt load along the way?

You are basically inviting private debt deflation dynamics in, which is what many economies were fighting just a year ago.

And since many of your trading partners are within the eurozone, what happens to private income in their economies?

You either have to get a productivity/innovation surge that allows you to sell more exports or substitute for more imports with domestic products, or you have to hope a fiscal revaluation, which will be mentioned in tomorrow’s installment, is both politically possible and effective in swinging the trade balance.

We wonder if the bond market will react negatively to the increasing sovereign debt uncertainty resulting in a March meltdown?

http://whatisthatwhistlingsound.blogspot.com/2010/03/march-market-meltdown.html

Government bond investors have been partially soothed of late by leaks regarding various fiscal assistance packages.

I do think amidst ongoing brinkmanship, these measures will hold, and fiscal restrictions will be undertaken.

My concern is what happens to private debt servicing as private incomes come under pressure.

So the “too cute” trade for a stretch here would be long the government debt, short European banks and European private debt…because most investors and policy makers don’t get the financial balance approach…even though it is just double entry bookkeeping.

“total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible capital during any accounting period. ”

Anyone who says this must not understand how the banking system works. This seems to be some fairy tale world where there is no such thing as fractional reserve lending. The whole REASON we are in this difficulty today is that banks, with the assistance of the federal reserve and regulators increased their loan leverage dramatically.

And banks often refuse to lend when savings are accumulating – that’s what is going on right now. Individuals are saving like crazy, and paying down debt, and banks are sitting on the new money instead of lending it out – out of fear of what is coming next.

The whole point of modern finance is that sometimes banks and investors WON’T lend money, out of a healthy fear of not getting it back, and at other times, lend out the same dollar 10 or 20 times – out of unrealistic optimism about economic conditions.

Anyone who says that “total saving out of income flows must equal total investment in tangible capital during any accounting period. ” is delusional.

dlr –

The savings = investment identity is another way of saying total money expenditures on final goods and services is equal to toal money income received from the production of final goods in services.

If you have found a way to break that identity, please do share.

It is typically spelled out in intro econ or macro courses as follows. In the simplest set up, with no foreign and no goverment sectors

Income = Expenditures on final goods and services

or

Y = C + I

where

C = consumption goods and services

and

I = tangible capital investment (plant and equipment, houses, inventory change)

Income (Y)received can be either consumed (C) or saved (S)

Y = C + S

then rearranging and simplifying:

C + S = C + I

S = I

There is nothing in that statement that assumes a fractional reserve system.

And as I discuss in the March 2010 Richebacher Letter, a fractional reserve banking system is generally not reserve constrained. But that is another matter entirely.

If your point is that banks finance deficit spending by creating loans out of thin air, there is nothing in that statement that violates the financial balance approach outlined in the guest commentary.

best,

Rob

I think a key thing to note is that the identity is for *financial* assets, that is, *claims* on others’ assets.

But it definitely possible for everyone to run a surplus in real assets or in total assets.

Suppose in a tribe of hunter-gatherers the hunters may catch 10 animals every week, eating 3, conserving 3 for the future, and giving 4 as a tax to the chief (~government). The chief may eat 2 and conserve 2 for the future. Both groups can continue to conserve more meat every week, no contradiction here. If, say, the chief has a debt of one animal to the villagers then he can pay it off using his surplus. This does not affect the total assets on his balance sheet or on the villagers’ balance sheet, since what they lose (gain) in actual animals they gain (lose) in terms of a financial asset (the debt). It is true, as stated in the article, that both groups cannot at the same time increase their total net *financial* assets (claims on each other), but it is possible for both groups to increase their total assets at the same time.

Tor –

One can contrive all kinds of barter with direct exchange examples, but they tend not to be very illuminating for the economy we inhabit. The idea of using simplifying assumptions is not to rule out the essential characteristics of the system you are trying to model.

However, your underlying point is well taken. It is important to remember while using the financial balance approach that net flows of money in one direction, to one particular sector, usually represent net flows of produced goods and services in the other direction. So a sector runnning a financial surplus has sold more goods (or at least more valuable goods) than they have bought from the remaining sectors.

Since some of these goods are durable, like capital equipment, they too accumulate over time on balance sheets as the real stock counterparts of these net production flows. Financial assets are then ownership claims on real tangible capital that accumulate as stocks over time when a sector runs a persistent financial surplus.

This takes us right to the problem Sir Greenspan considered back around 2000 when the US was still running fiscal surpluses, and the conviction was these surpluses would continue for “an extended period of time”. Eventually, the government was due to start accumulating ownership interests in the private sector if it ran fiscal surpluses long enough. Greenspan suddenly realized fiscal rectitude, if applied consistently, was a quick path to government nationalization of the private economy – which as a former Ayn Rand acolyte, he was reasonably concerned about.

So do think about that next time Pete Peterson and the Concord Coalition solicit funds so they can advocate in favor of fiscal surpluses as far as the eye can see.

best,

Rob

Rob,

I always thought of Kurt Richebacher as an “Austrian”, e.g. working in a loanable-funds framework. So I find it curious that you edit his newsletter. I’m sure you are more than qualified to do the job, but your own paradigm seems almost diametrically opposed and closer to Wray-Mosler-Aureback-Mitchell-Fullwiler. Where is the connection? Is my read on Richebacher wrong? Or do you find common ground between the two paradigms?

Thanks

Knapp

Dr. Richebacher was shunned by the Austrians. He was not pure enough.

He was able to work with the insights from both Mises and Keynes regarding what were once called “credit cycles”. There is some common heritage in Wicksell, at least up until Keynes’ Treatise on Money.

If you read Kurt’s letters, you will find as many references to Keynes, Robinson, Minsky as you will to Hayek, Mises, Haberler.

There are more overlapping themes than most people are willing to see, usually because they have an ideological axe to grind. There are also places where they complement each other, filling out empty holes in the theory. And there are certainly places where they just clash.

Kurt understood this. A handful of others do as well. It is a rich vantage point, but most people think it is crazy to even attempt such a synthesis. Maybe not…we’ll see.

I keep a foot in both camps as well – each has something to offer.

Good luck with the Richebacher Letter. The sample issue was very good.

“Spain is expected to reduce it’s fiscal deficit from roughly 10% of GDP to 3% of GDP in three years time, then the foreign and private domestic sectors must be together willing and able to reduce their financial balances by 7% of GDP. Spain is estimated to be running a 4.5% of GDP current account deficit this year. If Spain cannot improve its current account balance (because remember, it relinquished its control over its nominal exchange rate the day it joined EMU), the arithmetic of sector financial balances is clear. Spain’s households and businesses will need to spend 7% of GDP more than they earn over the duration of the next three years, thereby adding more private debt to their balance sheets.”

Can you please elaborate? Why must they spend more than they earn? Couldn’t they just just spend more of what they earn/save less, and that would eliminate their need to take on debt?