By Tom Adams, an attorney and former monoline executive, and Yves Smith

In common with other accounts of the financial crisis, the Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission report notes that mortgage underwriting standards were abandoned, allowing many more loans to be made. It blames the regulators for not standing pat while this occurred. However, the report fails to ask, let alone answer, why standards were abandoned.

In our view, blaming the regulators is a weak argument.

A much more sensible explanation can be found by asking: what were the financial incentives for such poorly underwritten loans? Why would “the market” want bad loans?

All the report offers as explanation is that the “machine” drove it or “investors” wanted these loans. This is lazy and fails to illuminate anything, particularly when there are other red flags in the report, such as numerous mortgage market participants pointing to growing problems starting as early as 2003. Signs of recklessness were more visible in 2004 and 2005, to the point were Sabeth Siddique of the Federal Reserve Board, who conducted a survey of mortgage loan quality in late 2005, found the results to be “very alarming”.

So why, with the trouble obvious in the 2005 time frame, did the market create even worse loans in late 2005 through the beginning of the meltdown, in mid 2007, even as demand for better mortgage loans was waning? It’s critical to recognize that this is an unheard of pattern. Normally, when interest rates rise (and the Fed had begun tightening), appetite for the weakest loans falls first; the highest quality credits continue to be sought by lenders, albeit on somewhat less favorable terms to the borrowers than before.

In other words: who wanted bad loans?

The dissents’ explanation is that the GSEs drove demand for affordable housing, which was what weakened underwriting standards. This might explain why the GSEs bought bad loans (which, oddly did default at lower rates than private market crappy mortgages, and thus didn’t contribute significantly to the GSE losses), but it fails utterly to explain why “the market” outside of the GSEs BOUGHT bad loans.

In the market for private loans, who wanted bad loans?

Had the FCIC report bothered to connect the dots raised by this simple question, it could have actually contributed something.

By blaming regulators (and the rating agencies), the report makes it seem as if it was just about what the lenders could get away with. But that same argument could be applied to any credit market, yet the US mortgage market was rife with remarkably crappy loans. And lenders still would suffer negative consequences for selling a bad product, even if they could get away with it for a while, such as loss of reputation due to inferior deal performance, losses on retained interests, and poor pricing for the drecky mortgages.

Along a similar line, the report notes that bonuses skyrocketed for the industry during the bubble years. Where did this money come from? Why had the mortgage industry never before generated such high compensation?

The obvious answer is that good loans did not generate hugely excessive bonuses, but bad loans did.

What happened is that the benefits for originating bad loans exceeded the cost of these negative consequences – someone was paying enough more for bad loans to overwhelm the normal economic incentives to resist such bad underwriting.

The best example of this is John Paulson, who earned nearly $20 billion for his fund shorting subprime. This amount of money was not ever possible or conceivable in the mortgage business prior to that point. The only way it could occur was through the creation of a tremendous number of bad loans, followed by a bet against them. Betting on good loans could never generate this much gain.

Given the massive amount of money earned by betting on bad loans, the logical next step is to ask, how did such incentives affect and distort the market?

Remarkably, the report never asks such a question. Yet the FCIC learned from Gregg Lippman of Deutsche Bank, who was arguably the single most important individual in developing the market for credit default swaps on asset backed securities (which allowed short bets to be placed on specific tranches of mortgage bonds) and related “innovations”, such as the synthetic CDO (a collateralized debt obligation consisting solely of CDS, nearly all of which were on mortgage bonds) that he helped over 50-100 hedge funds bet against bad mortgages. Didn’t it seem obvious to anyone at the commission that this information meant that a tremendous amount of money was invested in the market failing? What was the impact of this pile of money?

The report also fails to connect the dots about how Lippman and these funds accomplished their investment objective. Doing so would have allowed the report to draw conclusions about how the next crisis could be avoided.

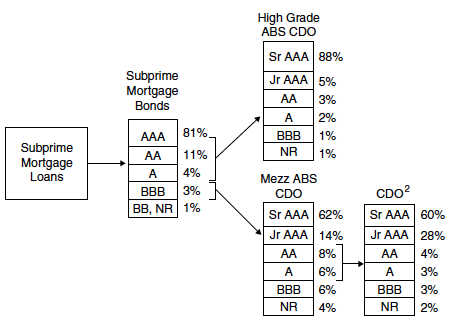

The introduction of a standardized contract on credit default swaps in the mortgage related market (which took place in June 2005….notice the timing relative to when the really bad mortgage issuance took off?) allowed interested parties to bet against the mortgage market in a remarkably efficient manner – through the use of CDOs. CDOs allowed investors to bet on the weakest mortgage bonds, the BBB tranches, which were a teeny but critical portion of the original deal (note it was cheaper to place these bets via CDOs than the ABX index, although some of the short sellers did that also). If the dealers couldn’t place these dodgy pieces, the entire mortgage bond factory would have ground to a halt. The last thing the dealers would want to be stuck with is the least desirable portion of a bond offering.

But conversely, this normally hard to place portion, precisely because it was the worst rated piece, suddenly became prized. Speculators could put a very small amount of money down and, if right, reap previously unheard of returns. For just a small investment in a CDO or CDS, an investor could create huge incentives for mortgage lenders to seek out unqualified borrowers and lend them far too much money (for reasons explained at greater length in ECONNED as well as in older posts on this blog, heavily synthetic CDOs pioneered by the hedge fund Magnetar were a particularly destructive way to execute this strategy. Those deals stoked the mortgage market directly, by using some actual BBB bonds, and indirectly, though their impact on spreads and the fact that pipeline players and other longs used some of the CDS not taken down by the shorts to lay off their risk, which encouraged them to stay in the game longer).

The report notes that many people saw the weakened standards and thought it was insanity and a serious problem. In fact, contrary to popular perceptions, many people in the securitization market thought the same thing. Some believed the problem would eventually cure itself, others thought there needed to be tighter controls. Virtually no one understood why the loans continued to be created, even after alarms were sounded. Almost no one recognized that there was a tremendous financial incentive for bad, rather than good, loans and that the alarms just made such bad loans more valuable. In fact, the alarms created a frenzy of more CDO creation as more hedge funds became aware of the opportunity to short the deals, which created demand for more bad loans.

The normal expectation was that warnings and threats about bad lending would have some impact on curtailing the bad loans, but it had the opposite effect: it led to more CDOs and demand for more “product” to short.

Dozens of warning signs, at every step of the process, should have created negative feedback. Instead, the financial incentives for bad lending and bad securitizing were so great that they overwhelmed normal caution. Lenders were being paid more for bad loans than good, securitizers were paid to generate deals as fast as possible even though normal controls were breaking down, CDO managers were paid huge fees despite have little skill or expertise, rating agencies were paid multiples of their normal MBS fees to create CDOs, and bond insurers were paid large amounts of money to insure deals that “had no risk” and virtually no capital requirements. All of this was created by ridiculously small investments by hedge funds shorting MBS mezzanine bonds through CDO structures.

Let us step through some simple math. If a hedge fund invested $50 million in shorting MBS via an equity investment in a CDO, it would lead to the creation of a $1 billion mezzanine ABS CDO (note this 5% assumption is conservative). In 2006, 80% of that CDO would consist of BBB or BBB- tranches of subprime bonds; remarkably, as much as 10% of that CDO could (and often did) consist of the lower-rated tranches of OTHER unsold CDOs, which would make the picture even worse, so for simplicity’s sake, let’s stick with the 80% figure.

So of that $1 billion deal, $800 million is composed of BBB rated bonds. $800 million also happens to be a not-bad number for the size of a typical residential mortgage backed security, meaning from the AAA tranches down to the so called equity layer of that first generation securitization. The CDO, the second generation, would be composed of about 100 BBB MBS bonds created out of these securitizations, and the deals in aggregate would reference about $84 billion worth of mortgages (note that in this example, the $1 billion CDO would take down or if it was synthetic, “reference” $800 million of BBB bonds out of total RMBS issuance of $80 billion. The reason the total amount of bonds issued was $80 billion while the mortgage amount was $84 billion was that the bonds were “overcollateralized” as a form of protection to investors. But as we have seen, this “overcollateralization” fell vastly short of actual losses).

Now even though that ratio is eyepopping, a $50 million investment versus $84 billion of mortgage loans ultimately referenced, it is hard at this level to ascertain the impact in any tidy way. The BBB tranche was hardest to sell and only 3% of the total value of the RMBS. It had served to constrain demand. But the dynamic flipped. In tail wag the dog manner, the pipeline started demanding crappy loans to get that BBB slice. There was a chronic perceived shortage of AAA paper, so the bulk of the subprime could be sold, and the other less prized parts could be dumped into other CDOs, which were also big fee earners to the banks.

But we can assess the market impact for a particular CDO shorting strategy, the one used by the hedge fund Magnetar, which used heavily synthetic CDOs, with roughly 20% actual BBB bonds, the rest credit default swaps.

A back of the envelope calculation, which leaves out the complicating and intensifying factor of the inclusion of lower CDO tranches in supposed first gen CDOs (put more simply, regular “mezzanine” or CDOs composed largely of BBB rated subprime bonds could be and were often 10% CDO squared; the so-called high grade CDOs, made mainly of A and AA bond tranches, could be as much as 30% CDO squared) shows that every dollar of equity in “mezz” (largely BBB) asset backed securities CDOs that funded cash bond purchases generated $533 of subprime bond demand [(1/3% BBB tranche in original RMBS x 5% equity tranche in the CDO) x 80% BBB bonds in the CDO].

You then gross that up for how many dollars of actual loans that represented, since it took roughly $100 of loans to make $95 of bonds, so the impact on the loan market was $560. The Magnetar structure was roughly 20% cash bonds, 80% synthetics, so $560 x 20% is $112. In other words, the impact on the loan market of the Magnetar structure was over $100 for every dollar they invested. And looking across its entire program, we’ve estimated, when making allowance for the effect of lower tranche CDOs in their deals, that their program alone drove the demand for at least 35% of subprime bond issuance in 2006. Industry sources have argued the total impact was considerably greater, both due to the effects of the synthetic component and the fact the structure was imitated by other hedge funds and dealers.

It is remarkable that the FCIC, with its access to industry figures and its subpoena powers, was unable to refine this sort of analysis together to give a clear picture of what was happening in the CDO market. The public deserves to know why Goldman, Paulson, Magnetar, Phil Falcone, Kyle Bass, George Soros, Deutsche Bank and 50 or more others were so eager to make these investments, why they wanted to keep the bad lending machine going, why they wanted to keep their strategies secret (even now), and how they made so much money so quickly. After all, it’s the rest of us wound up holding the bag.

Yves,

Thank you for explaining this in such detail. There is one piece that still puzzles me.

When this was all running at full speed, I can understand why people would want to issue bad loans (lots of fees) and why people would want to short the securities. But didn’t someone have to long the securities for someone else to short them. Who were the longs on this garbage? And how was it that they did not know that this was garbage?

Cough…all the pensions, municipality’s, unsophisticated (I make my commission of fees not results) ergo any one asking where to *park their money*…cough the very same people that bailed out the malfeasance after it went boom…cue evil maniacal laughter.

Skippy…ahhh those crazy Egyptians, just look at them, have they no shame, protesting really…

This is in ECONNED (you have not read it yet? :-) ) and you are gonna love this one….

The longs of the lower CDO tranches were correlation traders who didn’t care about credit quality, they were arbing one tranche versus another, plus OTHER CDOs (they went back into first gen CDOs, 10% of mezz and as much as 30% of of high grade, and some into CDO squared, and even CDO cubed. The most extreme, a CDO to the fourth, was of course a Magnetar trade, Octonian, which is a joke if you are a mathematician). The CDOs were a Ponzi (and exactly the same thing, CDOs as a Ponzi to keep the subprime market going past its sell by date, happened in the earlier, much smaller subprime market of the late 1990s).

But what of the AAA tranches? Well some of that went to monolines and AIG, some of that went to stuffees (IKB, those Bear Stearns hedge funds were actually big dumb players, and folks like town councils in the Arctic Circle. A remarkable amount relative to the size of its economy went to Australia). An otherwise not very good book by a CDO salesman makes clear that hookers, very expensive wine, and cocaine were important sales tools.

But…a lot, over half, wound up at dealer banks, particularly Eurobanks! And this is why the damned banks all were stuffed full of CDOs and had a systemic crisis! The CDOs were a catastrophic fail. The haircuts went from 2-4% for repo purposes to 95% in Sept. 2008.

Why? Under Basel II, they were perfect for bonus gaming.

If you took an AAA rated instrument, and hedged it with a CDS (and for most banks, you didn’t have to hedge the full amount, Basel II apparently gave you some latitude) it got a zero capital weighting. The act of taking that AAA instrument and putting on the hedge was called a “negative basis trade” because even if you had to hedge the full amount, you had income left over.

So let us say a CDO pays Libor + 50 basis points. You as Eurobank can fund at Libor – 20. So in theory, you have 70 basis points of income over your funding costs.

You buy protection on the CDO. That’s 30 basis points. You have 40 basis points of income post hedge.

Now from the trader’s P&L perspective, putting on the hedge is treated as “freeing up capital”. It’s an immediate credit. The economic effect is equivalent to take all the future income (those 40 basis points per annum, over the five to seven year life of the CDO) and discounting it to the present.

The traders are getting current year bonuses on future income, spread yet to be earned. And as we know, it was NEVER earned. The CDOs were spectacular wipeouts.

The role of the negative basis trade has not gotten the attention it deserves. These were incredibly easy and hugely profitable transactions for the traders involved. They were the ones ultimately screaming for more product! This mechanism played a direct role in the blowup of the financial system. That alone makes a compelling case for clawbacks and restrictions on Wall Street pay.

This is THE crisis mechanism, and it drives me nuts that no one in the officialdom can be bothered to understand it. It isn’t all that hard. If I could figure this out from my peanut gallery seat (admittedly with the considerable help of Tom Adams and couple of CDO moles, plus Andrew Dittmer and Richard Smith, who sanity checked), what is their bloody excuse?

Yves,

I’d just point out that it’s not only negative basis trade, but to an extent it can be any trade where the accounting is NPV based. In fact, the traders have to often explicitly “fund” their NPV, which is to borrow money to cover their profit so that the desk can show cash. That technically offsets the NPV over the life, but still it means they take profits up-front. Of course, one can argue that there are things like statistical provisioning and what-have-you requirements there, but those were in place for the negative-basis trade too…

That’s fair, and my impression (this is beyond what I had to get into for the book) is some risk management systems are more prone to NPV abuses than others. Do you have a point of view whether the EVA systems are better or worse on this front than the older versions like Bankers Trust’s RAROC?

Either can be weak; the two keys are the assumptions used (vol, correlation structure), and whether there is a transfer price for liquidity (both funded and contingent). Many firms lacked charges for contingent liquidity in their transfer pricing. See the Senior Supervisors Report “Risk Management Lessons from the Global Banking Crisis of 2008” at http://www.ny.frb.org/newsevents/news/banking/2009/ma091021.html for further information.

The same excuse the Mubarrak regime had for not knowing how unpleased the Egyptian people were. The system depends on certain things not being noticed and on believing certain things regardless of evidence to the contrary.

The part I can’t understand (OK another part I can’t understand) is why general populations have not reacted against this.

“This is THE crisis mechanism, and it drives me nuts that no one in the officialdom can be bothered to understand it.”

They’ll understand it when the populace sees it in a Road Runner cartoon format.

Good work on the New York Times Ed. page this morning.

Ah, this is where the magic comes in.

BBB were the tranches no-one liked – others got bought left right and centre (at least for a time).

So what better to do with BBB ones than to put them in another CDO, which will have a large bit AAA rated?

If you have a BBB market that is willing to purchase only say 10bn of the stuff, you can structure to your heart content until only 10bn of BBB is left, and the rest is in equity and AAA tranches – which tended to have buyers. Of course, all of that means is that the various structures are now even more correlated, as the single mortgage which used to live in one RMBS (well, maybe four or five with the doco mess we have), was now (indirectly) included in just about any CDO you could think of.

In fact, theoretically you could make the BBB tranche arbitrarily small, although the madness didn’t go as far as that.

In the Big Short Lippman says its the folks from Dusseldorf that took the long side of the bet. A lot of people took the longs because what happened could never happen house prices could never go down nationwide in the us. (Despite the fact that they did in the 1930s, many forgot about this or repressed it in memory, yet the facts could have been found by a trip to the library). The longs wanted yield and the worse the pool the higher the yield.

I’ve been a critic of Lewis’ book, he lionizes the shorts, gives a distorted impression of what was going on in the market (as if no one say the bubble but his heroic shorts, when as the FCIC recounts, a lot of people did) and fails to ask a lot of important questions. Plus Greg Lippman is hardly a disinterested source. “Dussledorf” is IKB, and it’s just not a big enough to have taken the bulk of the long side of this trade, not even close.

See this post for additional details:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2010/03/debunking-michael-lewis-subprime-short-hagiography.html

“The best example of this is John Paulson, who nearly $20 billion for his fund shorting subprime.”

Does this make sense?

You should know if you are a regular reader that I am unable to see typos. Thanks for the catch. Fixing now.

+ 31.1035

Thanks for the informative article

Jessica:

For myself, one of the revelations of the financial crisis was the casual approach many large institutions — the banks, the insurance companies, pensions — had to this product. In other words, the longs here blithely accepted the AAA ratings or otherwise took the word of the ratings agencies and the demand of the market itself as sufficient to invest in products that were claimed to be safer than sovereign bonds. (Remember how Greenspan and others said there had never been a national collapse in housing prices? or C. Prince’s comment that one had to dance as long as the music was playing?) If I am correct, then the authorities here and in Europe avoided a great deal of messy internecine warfare among the very large financial institutions and these hedge funds by passing the losses off on the public.

There is a bit of urban legend in this. The biggest need for AAA paper was not end investors, but traders who used AAA paper as repo, which is collateral for loans. Money market funds were big repo lenders, and dealer banks would lend to each other using repo.

The reason was they needed to post collateral for their derivatives exposures, and they could use AAA paper directly as collateral or post AAA paper as collateral to another party, get cash, and use that cash as collateral.

So this was much less about dumb investors relying on AAA ratings in the way it is presented in the popular press. You might query why people would be so confident in AAA paper for repo, but most repo loans were very short term (a month is very long in repo land, most loans are overnight to a week). It was only when AAA rated CDOs would get downgraded from AAA to CCC (junk) in a mere day that market participants realize how risky some supposed AAA rated paper was even for such short term loans.

So some of it was dumb investors and some of it was dumb money market funds and traders. At the end of the day someone has to be on the losing end of these guys massive gains, so back to your original question: “who wanted bad loans?” If people where unwilling to use these things for repos, there is no demand. If investors are unwilling to take them, there is no demand. If dealers are unwilling to keep some of the risk on their books, there is no demand.

Someone had to be long for these people to be short. So why did those people want to be long? From the title of your article I thought that was going to be the whole point.

I think it’s very possible that even if institutional investors like pension funds and insurance companies were a little suspect of the CDO AAA rated tranches, they were probably able to buy very cheap CDS insurance for the AAA rated paper.

Then we did have “the search for yield” the entire decade driving investors into longer term non USG debt.

Then when Greenspan started raising Fed funds, he had his conundrum about the long end of the yield curve not going up. Sounds like the combined demand of the repo market for collateral plus traditional investor demand, hoodwinked as they were,(which now includes central banks and foreign governments), all contributed to low long rates.

The demand for the mezzanine (risky) bonds of subprime MBS came, after 2005, almost exclusively from CDOs. In order for this to work, there needed to be takers of the AAA portion of the CDO. Early on, much of this demand came from AIG and, to a lesser degree from monolines and a few institutions like IKB. Later, investment banks like Citi and UBS became huge buyers of AAA CDO bonds, by gaming their capital requirements and bonus pools. Most of the mezzanine bonds from the CDOs went into other CDOs (and to IKB).

Because the CDOs had the effect of concentrating, rather than dispersing, risk, a remarkably small number of risk takers for “AAA” CDO risk had a hugely distorting impact on the CDO market.

and the desks jammed each around the street by charging different advance rates for similar type of paper which gave higher leverage.

(Remember how Greenspan and others said there had never been a national collapse in housing prices? or C. Prince’s comment that one had to dance as long as the music was playing?) If I am correct, then the authorities here and in Europe avoided a great deal of messy internecine warfare among the very large financial institutions and these hedge funds by passing the losses off on the public.

I am not buying the explanation that power to be were blind to dangers. I think it was more like they were desperate and saw that the only path for growth was this fraudulent financial activity and they consciously closed yes on all related criminal activity.

In other worlds they tried to postpone the day of reckoning hoping that something magic that can save the US skin, line happened with 90th come into existence. But this time they were wrong.

I think one of the key questions here is how independent are the large financial institutions from government and vise versa. Or in other words it’s difficult to pinpoint where government policy ends and where pure financial assets gambling (which BTW converted the world into US run casino — no small feat) starts.

My take is that TBTF are quasi-government organizations. It’s state capitalism in some form, I think. Or worse.

Yes, this is Yves at her best, first to disentangle the mess, and then to explain it very clearly. This is the brilliant part of ECONNED, and its worth buying and reading for this alone. Its the fundamental question, whose interests were served by the different steps that added up to the mess, and when you read the account in ECONNED, or the above, its difficult to argue with. This must be the answer. Any agency that really wanted to get to the bottom of this would start here and accumulate documentary evidence.

The great thing is, its falsifiable. It predicts what should be found in the evidence. If an investigation and documentation were done, we would be able to tell right away if this was wrong. But no-one really seems ready to do that.

Well stated; I agree.

And what this points toward, in my view, is the continuing legitimacy of government. When government can’t do something that one woman, with the aid of Tom Adams and CEO moles and a few others can pull off, what does it say about an entire federal government – let alone the failure of international institutions.

The details are complicated and I don’t follow them all.

But the main storyline is pretty simple: it was mostly based on fraud, screwy accounting, deception, and expedience.

It was one gigantic insurance fraud, and the failure of the US federal government to expose it, to prosecute it, but rather to attempt to cover it up and not even reign it in is profoundly damaging the legitimacy of the government. We’re starting to see this in a multitude of small symptoms.

should have been: “And what this points toward, in my view, is the continuing, damaged legitimacy of government….”

Apologies.

Reading through various posts in the last few weeks, I must say it had never occurred to me that one could misspell Deutsche Bank in so many different ways. Good post, though.

Need I remind you of what Mark Twain said about spelling?

I never had any large respect for good spelling. That is my feeling yet. Before the spelling-book came with its arbitrary forms, men unconsciously revealed shades of their characters, and also added enlightening shades of expression to what they wrote by their spelling, and so it is possible that the spelling-book has been a doubtful benevolence to us.

And one might throw in Emerson:

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds.

I actually was able to spell very well before I studied French. Go figure.

Before the internet, I too could spell.

I have that French problem too, especially in Latin America.

“Les faux amis” as my French teacher called the confusion from French derived English words. It applies equally to the sellers of MBS-CDO merde.

Once again, Yves, you’ve proven that you (and your NC colleagues) are National Treasures. Many thanks.

Fed lowering of rates took the gov’t bond option off the table for many investors. At the same time as long as bad loans got refinanced and remittance reports didn’t show rising delinquencies the warning sign the average investor was looking for was missing. The favorable 0% risk based rating of AAA mortgages was also very relevant.

The hours Wall Street spent figuring out how to shuffle loans and game the rating agency models was not something that was just not front page FT or WSJ material yet. Ditto for the fraud instituted by mortgage originators, especially at the broker channel, which would not have been obvious to many foreign and institutional buyers, fraud which should have been investigated long before it became obvious to main street.

I also discuss that in ECONNED. The low interest rates were a necessary but not sufficient condition. And the big need for AAA paper was for repo to serve as collateral for derivative and swap exposures, something I also discuss at some length.

Interestingly enough, The Fed in it’s just released meeting notes from five years ago discussed how the market was mispricing mortgages and the credit risk…Yet they did nothing.

Quote Yves: “what is their bloody excuse?” There are none so blind as those who will not see.

Where, pray tell, are the RICO indictments? Oh, I forgot, this was probably all perfectly “legal” fraud.

Hear, Hear!!

Why was there demand for bad mortgage loans?

Maybe the real question is, why so many people, who could not afford traditional mortgages, were trying to buy homes thus creating those bad mortgage loans?

Maybe the real story is indeed the stagnation of wages for most Americans, which drove them deeper and deeper in debt?

I also discuss that in ECONNED, but it is the LENDER that takes the risk in a loan, it is always presumed that there will be naive, overly optimistic, dumb, and crooked borrowers. So the idea that you will have some people who will be reckless or dishonest if you offer overly cheap loans does not have explanatory power. You need to understand why it made sense to create bad loans and why it went on for such a long time, particularly when so many people could see something was seriously amiss.

Should not be a shock to anyone that when you reduce the “price”(in terms of rates, underwriting minimums, etc.) of a deal you generate more buyers.

Same thing happened in the indirect sub prime auto finance market at the same time. Right around 04 the big players in subprime auto(HSBC, AmeriCredit, Triad, etc.) underwent a dramatic change in their underwriting. Up front fees charged to dealers were reduced; interest rates lowered; documentation reduced(proof of income, etc.).

From my standpoint(working for another subprime bank) it was sheer insanity. Not a chance in the world these deals made any sense at all for the banks. But their numbers exploded since they “created” so many buyers.

Your explanation of the mortgage scam makes sense out of the insanity shown in the subprime auto market of the same period.

I wonder if John Paulson shorted subprime ABSs?

Nobody was forcing borrowers to take out those loans they could not really afford over long term. Lenders were happy to oblige as well as to confuse and cajole, but ultimately it all started with the need to borrow in order to keep up with the growth of the standard of living.

Ahem, this moralizing misses a great deal.

First, there ARE instances of banks abusing customers in the borrowing process. For instance, there are documented cases of banks threatening borrowers, of ruining their credit when they were first given loan terns that looked affordable, then the mortgage broker offered loans with much bigger principal amounts (the threat was they’d sue and ruin their credit). This has been documented, there are news stories on this. Even if it happened only in a few cases, the fact that it happened at all is pretty stunning and speaks to how eager some parties were to sign up borrowers.

Another abuse is lenders promising one set of terms and delivering different documents at closing. I know a case like this, ironically a woman who has a PhD whose sister runs one of the mortgage counseling organizations in NYC. The borrower didn’t want to bother her sister, was told she was getting thirty year fixed rate, and at closing was instead given documents for an option ARM! She didn’t have the sophistication to check. There was also a story in the Wall Street Journal about programs to counsel borrowers to be more sophisticated in getting mortgages (as in how to do a budget to see what you can really afford) and they also taught borrowers what they needed to check in the contracts at closing. The story mentions in passing that one borrower had to have his closing rescheduled three times because the bank kept delivering contracts with terms considerably more unfavorable to him that what he was promised. One might be a mistake, more than once is policy.

I have also been told numerous times of people going to the bank to get a mortgage and having the bank tell them “You really can afford more” and pushing them to either borrow more on the house they were interested in or buy a bigger house. Per above, a lot of borrowers are financially unsophisticated. If the expert tells them they can afford more, they’ll consider that. And most people are optimistic, this is a well documented cognitive bias. Even if they know a lot of things have to work out right for them to borrow more and have it all work out well, a lot of people will underestimate the odds of Shit Happening.

Second, as we have recounted separately, there has been a lot of servicer abuse, misapplication of payments and compounding of junk fees which lead to improper foreclosures. It is remarkably difficult to get the customer statements from a servicer and untangle them; an attorney I know who had sued banks successfully says it is a pitched battle and takes a forensic accountant. Most borrowers who are foreclosed upon are by definition under financial stress and don’t have the resources for this sort of fight, and Legal Aid type lawyers can usually win these cases based on standing rather than what ought to be the real issue, improper servicer charges.

So the idea that everyone who is behind on their mortgage is the result of profligate borrowing is misleading and incomplete.

Yves, I am not moralizing. I am saying the problem is not just misbehavior of the financial segment – it is driven by the mis-allocation of income at the society level and stagnation of the middle class. Policing CDOs may force people to live in smaller and poorer houses but will not resolve the underlying fundamental problems.

MrM,

With all due respect, I still think you are missing the point a tad.

Even with the stagnant wages and financialization, we would have had only a savings & loan level crisis. It took the CDOs, the other leverage on leverage plays to create a global financial crisis. That has put the average person even further behind while enriching and entrenching the position of the financiers.

By rejecting the role of the complex and opaque instruments as vehicles for looting, you allow it to continue.

I wish everyone had your insight Yves. I am really sick and tired of those that throw the ‘borrower’ under the bus as a worthless no good. I, like you know lots of people that borrowed in good faith and today they are sitting on a house that has NO value…they have been downsized or laid off and they have run through their 401K and other ‘rainy day’ investments just trying to float above the water line. This fiasco was created by the John Paulson’s and those like him…Kudos to you for getting to the truth!

MrM says: “Maybe the real story is indeed the stagnation of wages for most Americans, which drove them deeper and deeper in debt?”

That is the real source of our Great Recession. And if there were not a large demand for refinancing, the financial crisis would have been much smaller. Once that demand was there the investment bankers, mortgage brokers, and the short traders had a playground.

Investment bankers found that the could sell residential mortgage back securities and make handsome fees. They demanded more variable rate mortgages which were normally made to subprime borrowers. These generated higher fees.

Mortgage brokers found that they could sell any subprime loan with very limited risks to them. Soon they were flogging their employees to write more of those subprime loans. Underwriting standards had to be reduced to get the quantity up.

Borrowers found that they could qualify for larger loans. Many more of them were being forced into the variable rate mortgages but they believed that they would always be able to refinance. They accepted that trade off in exchange for the new loan to pay off credit cards or other higher interest debt.

Once the playground had been set up, the short traders of subprime were just another player. No doubt they made the financial crisis worse but they didn’t increase the foreclosure rate.

“Maybe the real story is indeed the stagnation of wages for most Americans, which drove them deeper and deeper in debt?”

Stagnation of wages was/is side effect of stagnation of the economy. And I think that after short slowdown in 90th recently downward speed accelerated.

My this point of view allowing all this mortgage fraud and criminal asset speculation to happen was the sign of desperation rather then negligence. It was mixed with corruption, rising energy prices, etc: few things are pure but still I think fundamental problems with the US economy were the cornerstone of all this mess.

I think this is similar to what happens in communities experiencing economic decline: they open a few more casinos. Look at Pennsylvania. I read they opened six new casinos recently.

kievite said: “Stagnation of wages was/is side effect of stagnation of the economy.”

Actually it was exactly the opposite. The economy slowed as consumers wages stagnated.

Remember that about 70% of our economy is consumer spending. The American workers are the American consumers and when their wages stagnated so did spending spending.

This all began in about 1984 when the personal savings rate was 10.8%. By 2005 the personal savings rate was less than .5%.

From the Bureau of Economic Analysis Department of Commerce – Personal Income and Disposition:

From: http://www.bea.gov/bea/dn/nipaweb/TableView.asp?SelectedTable=58&ViewSeries=NO&Java=no&Request3Place=N&3Place=N&FromView=YES&Freq=Year&FirstYear=1984&LastYear=2005&3Place=N&Update=Update&JavaBox=no#Mid

Note: The 2005 savings number was less than 0% when first reported in early 2006. The BEA revised their methods in June 2007 and magically the savings rate had been positive!

In 1991 homeowners removed $56.7Billion in equity from their homes. By 2005 they were removing $577Billion in equity from their homes.

From a March 2007 study co-authored by Alan Greenspan:

From: http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2007/200720/200720pap.pdf

Obviously between 1984 and 2005 the American wage earners were coming under more and more pressure. Business and government were still doing well during that time period.

Outsourcing jobs to Mexico and southeast Asia had caused wages to stagnate long before our economy took it’s final dive.

The idea of “stagnating” or declining wages is a line that is not too often taken into consideration in this mess. It has been reported many times that “wages” of American labor have actually declined overall since the year 2000. To satisfy the “markets” for securities there had to be some kind of “renovation” of that market to continue the overall profits of the financial houses and the ability of the economy to further improve. Problem is that to “improve” our economy and continue the escalating profits in the face of declining wages for consumption especially in the “backbone” of American economy, housing, there had to be more aggressive innovation in securities and their marketing.

Sub-prime is not new thing. But, the escalation, greed and outright fraud perpetrated this time is historical.

With an unsophisticated, mostly TRUSTING mortgage consumer it was relatively easy to bilk both buyer and seller from beginning to end……and I agree with another who stated a passage similar to, “….you have to continue the dance until the end”…if you don’t someone else will.

That’s what historically brings down markets.

Human behavior. And, in this case trying to marry pure mathematics to human behavior just won’t work….ever…

It seems it was very easy to peddle the poison to any greedy “investor” who felt that he/she/corporation/bank/etc. could make more money than someone else.

It’s always forgotten that “…..someone is going to pay, but it ain’t going to be me!” (Wall Street Movie)

Anonymous Hedge Fund Manager:

[HFM:] It’s kind of an interesting interaction in the sense that a lot of this mortgage project was almost created by the bid for the CDO paper rather than the reverse. I mean, the traditional way to think about financing is “OK, I find an investment opportunity, that on its face, I think, is a good opportunity. I want to deploy capital on that opportunity. Now I go look for funding. So I think that making mortgage loans is a good investment, so I will make mortgage loans. Then I will seek to fund those, to fund that activity, by perhaps issuing CDO paper, issuing the triple-A, double-A, A, and down the chain.” But what happened is, you had the creation of so many vehicles designed to buy that paper, the triple-A, the double-A, all the CDO paper… that the dynamic flipped around. It was almost as if the demand for that paper created the mortgages.

n+1: Created the loans?

HFM: Called forth the loans, because it became a really profitable business. You saw where you could issue these liabilities.

[HFM:]…what happened is this machine—let’s call it, it’s a big machine that wanted to gobble up, you know, rated paper—needed to be fed. So there were people who could make a lot of money feeding the machine, and they were like, you know, “We need to keep originating mortgages, and feeding them to the machine,” and if you have a robot bid, you tend to get a bubble. Someone is hungry for paper, paper will be created.

And that’s almost never a good thing that lending decisions are being driven by the fact that many, many steps down the chain there’s just someone who wants to buy paper.

http://nplusonemag.com/interview-hedge-fund-manager

———-

“Our job is to create loans for securitization,” said an official from Wachovia Corp. (WB) a few years earlier. “We’re trying to manufacture the product that the investor base wants.” And so they did.

http://seekingalpha.com/article/91305-how-could-my-big-beautiful-loan-go-so-bad-so-quickly

This supports the idea that one of the real underlying problems with our economy, which resulted in the “financialization” and de-industrialization of Western economies, is the lack of real profitable investment. There is money to be invested and nowhere profitable to put it. Thus, the creation of fictional and fraudulent financial investments to reap profits.

Ah, the irrational logic of capitalism.

Yves

Can u contact me via email? My partner and I have something importantly attractive and very valuable that we would like to discuss with you.

Thanx.

Bob

In the end, did it not, skew the entire market, poison the credit water hole, *by* the water hole deities *themselves* and they blamed it on the music?

Skippy…sorry its just that the FOG is some times so thick, ramifications so broad.

Yves, great repsond in NYT’s Room for Debate: “Was the Financial Crisis avoidable?”

Best from Zurich.

I think one needs to step back even a bit farter. While not at all disputing Yves story, perhaps we should consider the effect of sizeable trade defecits run by our country over a number of years. This left exporting countries long dollar. China recycled its dollar holdings by purchasing Treasury and “quasi-Treasury” GSE debt. Market economies such as Germany and France recycled though exchange rate movements, bank and private sector investments. Witness the early problems in the crisis in summer/fall 2007: BNPP suspending three funds shortly after the Bear Stearns High Grade Enhanced Leverage fund debacle, the failure of SIVs sponsored by German banks, etc. Chinese purchases would have pushed down short rates, while european invesments would have driven down credit spreads. Both would lead to 1) easier housing credit, 2) more maturity transformation in the banking and shadow-banking sector.

Yves,

A very good explanation.

Who wanted to buy the dreck?

Who wanted to short the dreck?

How can you create the dreck?

In her response to the first comment in this post, Yves appears to be giving one possible response to the dissenting FCIC commissioners who said the issue couldn’t possibly be “people”-related regulatory failure because the same crisis happened in European banks subject to different regulatory regimes. Therefore, the dissenters said, it must have been “policy”-related. But Yves’ explication implies that if the Eurobanks went into crisis because of scams on our side of the ocean, the crises on both sides of the Atlantic were highly correlated.

So David it comes down to whether it was demand-driven (European investors chasing yield by purchasing any asset with a higher yield for an equivalent credit rating) or supply-driven (bankers created and then sold fradulent products). I tend to be a Minskyite, so I believe more strongly in the endogenous demand-driven yield chasing that subsequently caused the controls around the product to break down.

For a good discussion of the of the breakdown of the incentive chain, I would recommend “Understanding the Securitization of Subprime Mortgage Credit” by Ashcraft and Schuermann at http://www.newyorkfed.org/research/staff_reports/sr318.html

Merrill was another big retainer of CDOs via what amounted to accounting fraud. Louise Story at the New York Times broke this story with their Pyxis vehicle. So you had major US players engaged in similar practices via different mechanisms.

A classic case of rational irrationality.

Rational for the bettor and irrational for almost everybody else.

When a persistent and severe pricing insanity prevails it is a clear warning sign to look for rationally irrational strategies within the system and remove the distorting incentives.

What have we learned?

Yes, the markets may self-correct, but at the expense of external actors.

Endogenous shock, exogenous payers.

Tom,

I don’t usually disagree with you as strongly as I do today. Your analysis is quite wrong. The reason that the mortgages continued to be made was NOT market demand or buy-side equity or mezz tranche buyers, rather it was the profitability of vertical integration to the sell-side. Banks made enormous amounts of money on warehouse lending to third party originators, made money securitizing the MBS, made money servicing the MBS, made money trading their own MBS, made money securitizing the mezz tranches into CDO’s… Remember, the natural buyer for the investment grade tranches of MBS were investment grade only buyers (not hedge funds), the hedge funds were buyers of mezz and equity tranches of RMBS.

By late 2005 early 2006 there were few natural buyers of mezz and equity tranches of RMBS so the sell-side sold almost 70% of mezz RMBS tranches into CDO’s as a way of using the alchemy of ratings to create more investment grades to sell to charter constrained investors.

Notice that by this time certain sell-side firms were already slowing their involvement in the cash CDO origination market. Anyone who was watching understood that the demand for mezz and equity tranches of RMBS was waning and that was driving the investment banks to put more and more crap into the CDO pipeline as a way of clearing their inventories.

Smart firms, recognizing this saw the opportunity to use synthetics to take the other side of the trade. That is what markets are about, investors, recognizing mispricing of assets and risk and betting the market will come to recognize their view as correct. At the time the hedge funds were putting on the trades they were far out of the money bets and 99% of the street disagreed with them. They were taking huge risks of being wrong and consensus said they certainly would be wrong.

You can read my co-authored papers from ’07 here:

“How Resilient Are Mortgage Backed Securities to Collateralized Debt Obligation Market Disruptions?” (February 15, 2007)

http://www.hudson.org/files/publications/Mason_RosnerFeb15Event.pdf

“How Misapplied Bond Ratings Cause Mortgage Backed Securities and Collateralized Debt Obligation Market Disruptions (May 3, 2007)

http://www.hudson.org/index.cfm?fuseaction=hudson_upcoming_events&id=393

Now, if you want to focus on the issues not addressed in the FCIC report, if one looks closely at the document behind the investigation it appears the FCIC failed to highlight perhaps the most central issue in the crisis – warehouse lending. Documents in the FCIC archives demonstrate that at least one of the rating agencies was aware, before they began do downgrade securities en masse, that the Wall St banks were aggressively cleaning out their inventory of securities and selling them to investors. Other documents demonstrate that at least one large firm was aggressively seeking to offload risks they had intended to retain by moving them to sales traders and arming sales-traders with information to use to move those risks, even going so far as to choose specific firms to target. Clearly, they believed in the greater fool theory, the question is did they make honest representations to those they sought to fool. Culpability seems clear, and I would think legal action should follow, but as is the case with most “gold panel” commissions, those who control the game make sure they can skate away.

Just red your response Josh. And this sounds spot on!

I don’t see the disagreement. Could you explain why these explanations are mutually exclusive?

Prior to widespread buying of mezzanine MBS by CDOs, MBS sellers had to convince cash buyers and monolines to buy the mezz bonds in order to get their deals done. This limited the growth of the MBS market. As underwriting standards began to weaken, cash buyer and monoline interest in these bonds declined. This is a normal reaction and, in the past, had served to correct the market without causing a global crisis.

Rather than slow issuance, in reaction to waning demand from cash buyers, however, issuers increased issuance because a new source of demand had been created – CDOs.

I, and many of my peers, were quite worried about weakened underwriting standards and a home price bubble by 2006 and most were on the sidelines, waiting for the subprime market to correct. We couldn’t understand why the demand for such weak loans and bonds was so strong. Credit spreads for BBB MBS were at historically tight levels and it was incomprehensible how anyone could find the risks and rewards of these bonds attractive at those prices (bond insurers were told their premiums would basically have to be negative to win a bid for a subprime deal. If insurers, levered over 100 to 1 at the time, couldn’t make the return work, who could?).

Demand from CDOs drove the origination of more loans at a time when the natural buyers were exiting the market. If not for this CDO demand, origination would have slowed. So long as their was a willing taker of the super senior risk of the CDO, the CDOs were excellent long counterparties to those shorting MBS.

It sounds like what you are describing, Josh, is not inconsistent with the way we’ve described the market. My only disagreements are that many people were worried about the underwriting risk, but few were aware of the implications of shorting MBS and that CDOs were effectively the long counterparties. In addition, I am not convinced that those people shorting MBS were taking enormous risk – they were actually putting a relatively small amount of cash at risk, compared to the amount of potential upside- this was also poorly understood by most participants in the market. Some also figured out ways to fund their short positions via the CDO structure to virtually eliminate the cost and risk of the short premium.

Who wanted the bad loans?

Well from the following, the GSE’s ramped up their investments in subprime MBS’s (probably the investment grade tranches) from 2003 to 2006

http://www.villagevoice.com/2008-08-05/news/how-andrew-cuomo-gave-birth-to-the-crisis-at-fannie-mae-and-freddie-mac/2/

Note the following in the above referenced article:

When HUD released the next set of goals in 2004, it reported that after Cuomo’s previous edict, there had been a sudden spurt of GSE subprime investment, “partly in response to higher affordable-housing goals set by HUD in 2000.” Fannie had gone from $1.2 billion in subprime-mortgage and securities purchases in 2000 to $9.2 billion in 2001 and $15 billion in 2002. Freddie’s numbers were murkier, but clearly also on the rise. In 2003 alone, the two bought $81 billion in subprime securities—which also count against the goals.

Fannie also developed a “flexible” product line, providing up to 100 percent financing and requiring borrowers to make as little as a $500 contribution, and bought $13.7 billion of those loans in 2003. In addition to subprime loans and securities, both banks burst into the “alt-a” market, making alternative products easily available to borrowers who had slightly better credit histories than subprime borrowers, but were unwilling to provide full documentation of their financial histories. (It was the “alt-a” investments that recently brought down the private bank IndyMac.) These risky adventures, according to the 2004 HUD report, prompted Freddie to claim that “the increased goals created tension in its business practices between meeting the goals and conducting responsible lending practices,” a self-serving attempt to plant the blame back on HUD.

After this initial uptick, the two banks purchased $434 billion in securities backed by subprime loans between 2004 and 2006. The Washington Post noted this June that the GSEs’ aggressive acquisitions “created a market for more such lending” by others, feeding the fire. No one knows just how big a bite the subprime mess is now taking out of the GSEs, or how much of that portfolio will ultimately go bad, but it has become axiomatic that, whatever the total, it is too much, since it will have seriously shaken confidence in these two linchpin institutions.

(Alan Greenspan expressed suprise in late 2005 when shown data that the subprime market was 25% of the mortgage market in 2005)

Also from

http://blogs.ft.com/economistsforum/2008/04/alan-greenspan-a-response-to-my-critics/

From the above “The core of the subprime problem lies with the misjudgments of the investment community. Subprime did not break from its localized niche status until 2005. As Ben Bernanke recently put it: “The deterioration in underwriting standards …appears to have begun in late 2005.” I assume that judgment reflected the increased delinquency behavior that is now evident for loans initiated in late 2005 and subsequently.”

Also on page 146 of “13 Bankers”, it is stated that “These purchases of MBS were a mechanism by which government pressure to increase lending to low-income Americans translated into greater demand for mortgage securities and therefore greater profits for Wall Street”

Based on all of the above, one can make the case that the GSE’s stoked the market for MBS’s made up of subprime loans, indeed if the GSE’s did not ramp up their purchases of MBS’s when they did, the housing bubble may have burst in 2004 instead of mid 2006.

Of course given the demand for AAA tranches of MBS’s and the money to be made on those, Wall Street could always be counted on to come up with ways to dispose of the 15% of the MBS tranches that were not so much in demand.

Fannie and Freddie did buy AAA tranches of subprime MBS. But these AAA tranches would not have existed if the issuer could not sell the mezzanine bonds of the deal, especially the BBB level tranches, which is where the risk of the mortgage loans was concentrated. The demand from these bonds came from CDOs. Without strong demand from CDOs for such risky bonds, credit spreads would have widened, MBS issuance would have slowed and fewer loans would have been originated.

CDOs were the irrational “investors” Bernanke was referencing (though he may not have known it). He references 2005 as when the underwriting standards deteriorated, the year that CDS for MBS was created and CDOs began to gobble up massive amounts of mezzanine MBS bonds. That’s when shorting of MBS began.

We know from the news that AIG came in big time selling CDS protection. I’ve assumed it was on the mezzanine layers of structured MBS, or on the whole CDS that the IBs were using as a garbage disposal to dispose of their unwanted, hard to move inventory. Some of the CDS dollar amount did get transmuted to AAA using math, then the crappy part was left and needed an insurance policy to sell it. Then the IBs did get stuck with a lot of the inventory too. Plus Ben inherited quite a bit.

I haven’t seen any “official” reports on supporting my assumption here, but it seems a reasonable guess.

Oops, typo. “…or on the whole CDS that the IBs…”

I meant CDO, not CDS here.

Lew Ranieri has also confirmed 2005 as the pivot. I saw him say at the April 2008 Milken conference there were 5-6 quarters of really really bad loan issuance, and the shift was dramatic, and it took place in the third quarter of 2005. He was then at a loss to explain it, and it was clear he was appalled.

Josh,

Your warehouse line explanation is important but insufficient. Just because a product is hugely profitable to you does not mean you will be able to find buyers. The first rule of a business is what it takes to have a business is customers. God only knows how many businesses fail because they think they have a winning product but not enough customers want it.

And by ALL accounts, demand for crappy mortgages was superheated in the late 2005 to 2006 time frame. If you can’t explain that, you have failed to explain the crisis.

I got considerable input from two people on CDO desks. These are the ONLY people with a complete view of what was happening, most important, where the trades were going and what the drivers were. By my rough estimate, there are fewer than 100 people in the world who were in these roles at the major players.

I did not go looking for this explanation. These traders came to me because I had been chipping away at CDOs. I had a sense they were really important and was frustrated at the lack of any decent information about them in the public domain. Tom, who had had a seat at the table on some of these transactions but lacked a full view, was at a loss to understand some critical elements of happened until we got their input. It came from the CDO market participants, and for the most part, this community has been completely close mouthed.

“And by ALL accounts, demand for crappy mortgages was superheated in the late 2005 to 2006 time frame. If you can’t explain that, you have failed to explain the crisis.”

Yes, this is the heart of the matter, and Yves is the one who saw it clearly first. Well maybe the only one who has seen it clearly so far, at least publicly. Certainly the only one who has explained it clearly.

Josh,

I also disagree 100% with your “huge risk” assessment. The only party taking a lot of risk (arguably) was Paulson, and that was by virtue of a PORTFOLIO decision he made, which was that contrary to normal preferred hedge fund practice, he allocated a huge portion of his fund to this trade. Normal practice would have been not to take such a concentrated bet. And even then, he constructed his trade by holding a large Treasury position and used the income to fund his CDS premiums. So even he was not in a negative carry position before the market turned in his favor. He has NO risk of loss in his trade as he executed it.

The only exception arguably was Michael Burry, but that’s really not due to the risk of the trade per se, but that he was guilty of massive style drift. His investors were upset that a guy who seen as a stock market genius was suddenly putting a lot of capital in the credit markets, which was not what they had hired him to do for them. And I have to tell you that Burry’s behavior toward his investors was abominable, in that he froze withdrawals, and on top of that had a $1 million shortfall! Not being able to keep proper books is a hanging crime in that space.

CDS were remarkably underpriced. 100-120 bps to short BBB bonds on subprime mortgages? That was the insight. It was not MERELY that the subprime market looked sure to tank, it was that there was a VERY cheap and efficient way to play it, by targeting the first loss tranche, and the way to play it was incredibly low cost.

And you have the most destructive player completely wrong. The Magnetar trade was a NO RISK trade. It had positive carry! We document how it worked. Magnetar could load that trade all day and sit tight until the mortgage market blew up. It was an utterly brilliant trade, it solved for the one problem of being short, which is you look like an idiot and are losing money until the market turns. And that’s why it was imitated.

I believe the FCIC did not address this because it had all been previously explained quite understandably to the morts: big government, liberal socialists made us do it with that evil CRA which intended to earn the votes of the illegal aliens by allowing them to profit from the American Dream (which they were most certainly not entitled to do) by lying to the poor, unsuspecting, American exceptional banking institutions.

Have we all forgotten ACORN, that most insidious and subversive of “community organizations?”

Sarcasm OFF.

Analysis: a deliberate cover up –

http://www.counterpunch.org/whitney01312011.html

When I saw the headline I thought, finally, someone is going to tell me about the inexplicably idiotic “investors” who bought all that mortgage junk without even doing spot-checks of whether the MBS contract terms were fulfilled!

Oh, well. Still an interesting post, but not what I hoped for.

Why weren’t the pension-fund managers (if that’s who it was) fired, and sued for malpractice/malfeasance/incompetence?

Don’t you need some sort of professional license to manage a pension fund? Shouldn’t you lose it for being so careless as to buy MBS without checking that the terms of your contract have been fulfilled, and your investment is indeed secured by the homes, bankruptcy-remote, and tax-advantaged as promised?

Ah, just read Yves’s first comment, the reply to Jessica, and it looks like I need to read ECONNED! (Been meaning to, but am scared it will make me too depressed.)

No, it won’t make you depressed, its actually exhilirating. The first part can be skipped unfortunately, its an ideological canter through economic history giving a standard point of view you can find anyplace, and Yves adds nothing to this, and its not necessary.

Then you come to the exhilarating part. Mind like a steel trap comes to mind, she shows an absolutely extraordinary ability to disentangle the different threads and to show you how they all combined together to lead to the unsoundness and the crash. Its amazing. You see how the different perfectly rational motivations worked, and how people all did things that made sense from where they were standing, and how the results were totally insane. You’d never in a million years work this all out for yourself.

Read it. Just skip the part about economic history, its OK if you like that sort of thing, but if that’s all there was, you wouldn’t buy it. What you buy it for is the last two thirds, and that is pure gold.

Thanks for your glowing recommendation, but I think you are showing your biases. I’ve had economics professors praise the first third. It is not as old hat as you would imagine particularly the discussion of Samuelson, the “Keynsians” v. Kenyes, ergodicity, and how “free markets” ideology was sold.

Even if this is a longer discussion than you might like (and it winds up being the wonkiest part of the book), this exposition is necessary to establish that mainstream economics is an ideology and most of financial economics isn’t just bunk, but is actually dangerously misleading.

The ideology helps keep bad practices intact. Until this ideology is questioned on a widespread basis, we are just setting ourselves for more financial crises. So that part may make for less exciting reading, but I would not recommend skipping it.

I agree that the first part of the book is well worth reading and if it is common knowledge, as the poster seemed to think, I never heard of it. It is not just a summary of economic concepts, but more the story of how certain economic views captured parts of education, law, and politics, setting the stage for the raping and pillaging that we recently witnessed.

Yves, I don’t know what your definition of wonkiness is. I found the 1st part of the book pretty easy to follow, but when it gets into the story of what actually was constructed that turned into the crash — as a non-wall street type, following all the constructions and interactions made my head hurt. I still can’t say I have really digested much of it, nor do I care to, but I am much better informed now than most people from the book.

I read a few books after the crash trying to get handle on what had happened. Econned was the only one that left me satisfied that I had gotten a true and rather complete story. I also got some insights (mostly from the 1st part) that I wasn’t expecting.

“MBS contract terms were fulfilled!”

Sounds like a big part of the problem was that buyers of the end product, fund managers or anyone else, aren’t allowed to look how the sausage was made. The only one’s that got loan details outside of the IBs (and friends like Magnetar and Paulson, whom bought the equity tranche to enable the deal, then made much more shorting or buying CDS protection on the next riskiest tranches) were the rating agencies. They then handed out ratings based on the flawed statistical models handed to them by the IBs. The the IBs were making guarantees as to the accuracy of information and that things are handled by the terms of the PSA. (you aren’t allowed to visit the REMIC either and look for loan docs)

The buyers never had a chance, unless they subscribed to the “if you don’t understand it, don’t buy it” rule. Apparently there were many that were too trusting in our sophisticated financial industry.

And some like Pimco, Blackrock, the New York Fed and others are beginning to make noise about suing for information about what they were sold.

Check out the Steve Rattner problem in New York, pension fund placement and disintegration is where the money is.

Investment professionals are herd animals. They live and die by their benchmarks. Better to be stupidly wrong going along with the herd and over the cliff with everyone else, than to stand aside “while the music plays” and miss a few quarterly benchmarks. The latter gets you fired. The former — oh, well, who could have known.

I’m a novice, but here is my take: Johnson, Magnatar and GS were betting on the time-lag it took for the ratings agencies to correct their ratings of these tranches. Most fund managers took their cues from the ratings agencies. The congressional hearings made it clear they intentionally overrated these MBS, and of course they were reluctant to correct that for fear of losing face and being the ones to spoil the party.

Apparently Johnson, Magnatar and GS bet correctly. If anything, the reputation of the ratings agencies should have been destroyed.

Far be it for me to let regulators off the hook, but it is important to remember how anti-regulatory the climate was in the 1990s and 2000s. Greenspan, Bernanke, and the dominant neoclassical economists didn’t believe in regulation. They thought the markets were self-regulating and self-correcting and that they would punish any wrongdoing on their own. This anti-regulatory ideology made big strides under Clinton but reached its apotheosis with Bush where anti-regulators were put in charge of regulatory agencies pretty much across the board in government. It wasn’t just financials. Rolling back or not enforcing existing regulation was pervasive.

I would also cite the 2003 pre-emption of state attorneys general investigations of predatory lenders by the Office of the Comptroller. This was not an example of regulators standing pat but rather one where the anti-regulatory political appointee who headed the OTC was actively protecting the predatory lenders. This environment made possible the scams which Yves describes. The FCIC report is a whitewash precisely because it doesn’t establish the context in which all this took place and only looks selectively at what did happen. It’s like they walk into a room filled with elephants, see one or two, blame the cleaning staff for the shit on the floor, and never ask why there were elephants in the room in the first place.

Greenspan’s mistake, according to him, was to assume that someone working for a bank wouldn’t do anything to completely blow it up.

Since such people don’t fit into his model, the people must change.

The anti-regulatory fever was strong and on the street where I worked it was impossible to whistleblow. Anyone knew by 2006 that the loans being funded were not rational, but the response to me by organized real estate and my own office was not to interfere with someone’s commission. On the theory that state laws matter, fraud was being committed, fat cats usually get to walk, I got out. Angelites says let the facts in the report speak. Of course he is being bashed by the right who are trying to blame F/F. Angelites was the rare honest politician in Sacramento and I’m glad he got the job. Yves Smith is the best at unraveling what ended a 35 year career for me.

They thought the markets were self-regulating and self-correcting and that they would punish any wrongdoing on their own. Hugh

How can government backed counterfeiting in the government enforced monopoly money supply be self-regulating?

Bankers should choke on their own hypocrisy.

Yves& Tom

Brilliant.

But, amongst the FCIC and the staff, how many are capable of understanding this even if they had the motivation to take the time to understand this?

How many could have presented the case as your presented it, while understanding what you wrote?

And, for those who did understand, how many threw up their hands because those around did not have the knowledge or motivation to understand this?

Same question as to;

Members of Congress and their staffs.

OCC and staffs.

Financial reporters.

The White House including Economic Advisors.

Dept. of Treasury

SEC

We both tried very hard to get their attention through multiple channels. They talked to us only as a matter of form, me in November and Tom in December. By then they were not prepared to consider new ideas (as in they listened but I was certain it would not be incorporated in a meaningful way into the report).

Let me guess –

After the meeting, you received an e-mail or letter saying:

“thank you for your helpful comments…”

ps:

That was the standard comment from a famous DC law firm that helped drive a client of mine into bankruptcy – they wrote a letter to the SEC (from a partner who was a former senior attorney at the SEC) based upon the misunderstanding that a basis point and a percentage point were the same, complaining about the size of a 5 basis point guarantee. Of course, the recipient at the SEC did not know the difference either. When this was pointed out to the firm, the response was one line – as above.

There were a lot of reasons that AAA tranche inventories at CDO underwriters were allowed to build to extreme levels (i.e, $50bln+ at MER); positive carry (repo fodder), low RBC charges, misplaced confidence in the ratings and/or effectiveness of the hedges, unwillingness to shut down the factory in the face of growing buyer fatigue, and suspension of basic risk management. But the single biggest reason was…that the P&L of the CDO origination teams was based on production, not final distribution. Yes, that’s right, people were getting enormous bonuses based on CDO’s that were created only to be warehoused or repackaged, and never completely sold. Unbelievable…

{{It’s interesting as youth are bent towards being liberal and morph into being conservative when older, the transitional period is seen as internal conflict}}

I advocate “follow the money” in all kinds of examinations involving government and private business, but the housing bubble (upon which everything else was piled), contained an interesting, and quite simple really, kind of logic in that it all depended on rising perceived values.

In housing, the perception becomes the reality for finance. I saw it up close with my real estate syndication business. The temptation to play the game of ‘properties-like-stocks’ is almost irresistible.

Here is the scenario. When real estate finance (and refinance) depends on rising perceived values (the formal appraisal), only market pressure can do this. That means a continual stream of banking and mortgage brokerage customers for real estate finance and refinance.

Only so many customers qualify for prime mortgage financing. I call this one ‘swath’ of customers. Successive ‘swaths’ of customers for financing are less and less qualified leading to the worst of sub-prime loans. Note: so far everyone is making a lot of money on this.

Then, there are no more ‘swaths’ to qualify in any way to continue upward pressure on real estate prices. This ‘supply’ simply runs out. Demand for loans doesn’t cease, but underwriters’ ability to devise new lending programs for even less qualified borrowers ends. Upward pressure on prices wanes, and real estate market prices crash, leading to the cascade of occurrences that we call the world-wide financial collapse (or near collapse) of 2008.

In my case, I saw an aspect of the ‘game’ on the investment side of it. An example is what I saw in one neighborhood in Southern California, the “Newport Heights” neighborhood above Newport Beach. In 2006, it was a mix of large mansions, 8,000 square feet and bigger, and a lot of little old houses on fairly large lots, houses dating from the 1930s and 1940s, and older.

One in particular I looked into showed a property profile transaction history of purchases, holding periods, then resale amounting to three or four transactions in a period of one year. Each successive buyer was buying to hold for the rising market, then selling for a profit. The house appeared unoccupied and with a dead lawn. It was all just like trading in commodities or stocks.

Hi Yves, this analysis points very well to the next black swan event. One would think then that the big players would want to buy debt obligations from the lowest rated sovereign states, such as Ireland and Greece. Is there any proof that this is really happening? Or are they staying away due to the higher probability of a naked default? Just thinking. I know the ‘insurance’ implied by a BBB MBS CDO is different from a sovereign CDS, however, it just makes the mind wonder.

I don’t have anything meaningful to add, but the comments on this post are amazing. I need to reread Econned.

If I got this right, it all sounds as if some people on Wall Street were buying insurance policies on the lives of unsuspecting victims while deliberately encouraging a suicidal life style and providing them with the means to accomplish that goal. This can’t be legal, can it?

It’s fairly clear from the timeline that the FCIC Report “misses” the central issue by design. I was never intended to find critical fundamental flaws in the system but to retroactively endorse the bailouts and ensure continuity of the wretched status quo, the “new normal”.

This is a fascination thread. Now that I know what Econned is about, I am going to make it my next purchase. I too saw this up front as the losses in subprime being much less than was being discussed. But at the same time, I worked through much of the 1980’s housing bust here in DFW which took down many of the S&L’s. The problem was going to be much larger than sub-prime. By mid 2007, I could see that there had been way too many houses built for the market to stand up and the losses were going well past subprime. There wasn’t any subprime here in the 1980’s, but there were loans with huge fees loaded in and deferred interest loans, as the late 1970’s and early 1980’s had built in the same assumption, the rise in price would pay the charges. But, in the end, it became impossible for the average Joe to sell his home, refinance it, etc. That boom too had been built on fees, mainly in the flipping of land, the building of subdivisions and the mass building of homes to the extent the market couldn’t consume them all.