By Satyajit Das, the author of “Traders, Guns & Money: Knowns and Unknowns in the Dazzling World of Derivatives”

In early 2010, drawing on the military leadership of President George W. Bush, European leaders declared the economic equivalent of “mission accomplished”. A bailout – whoops support! – package of Euro 750 billion had shocked and awed speculators into submission. Like the Bush pronouncement, the European prognosis provided premature. The return of European sovereign debt problems in late 2010, culminating in the bailout of Ireland highlighted the deep seated and perhaps intractable problems of some over indebted European nations.

Mission Interrupted

In the first half 2010, the trigger was the large budget deficits and high debt levels of the “PIGS” (Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain) or “PIIGS” (including Italy). For Greece, a lethal cocktail of the need to finance maturing debt and deficits, use of derivatives to disguise debt levels and general lack of candour about its borrowing, exacerbated the problem.

The European Union (“EU”) responded ultimately with a variety of measures, including an Euro 110 billion bailout for Greece and the Euro 750 billion European Financial Stability Funds (“EFSF”) designed to underwrite the liquidity of the besieged Euro-zone members.

The European Central Bank (“ECB”) separately supported the EU measures. The ECB’s role, presumably with the tacit agreement of the EU and members, was crucial, avoiding the problems of lack of consensus and disagreements at the political level.

The ECB purchased bonds issued by Greece, Ireland and Portugal in the secondary market to support prices. By mid-December 2010, the ECB had purchased Euro 72 billion as part of these operations.

More importantly, the ECB supported banks in the troubled companies, providing funding when money markets would not finance these institutions. The funding was at attractive rates (around 1%), against security of government bonds lodged as collateral for the loans. A delicious arbitrage and backdoor way of financing the troubled borrowers ensued.

Domestic banks in Greece, Ireland, Portugal and Spain purchased their own government’s debt, ensuring crucial demand and “successful” auctions. The purchased bonds were used as collateral to secure funding from the ECB. The illusion that the countries had access to commercial funding sources at reasonable rates was maintained. The banks also earned large returns, the difference between the yield on the bonds and the ECB funding rates.

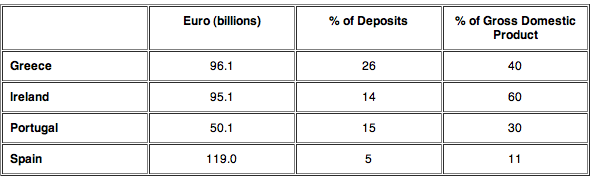

As of August 2010, the level of ECB funding was as follows:

Following the Irish crisis in the second half of 2010, the funding demands on the ECB have increased. Ireland’s borrowing from the ECB has reached Euro 136 billion (86% of Gross Deposit Product (“GDP”)), around a quarter of Euro-zone member drawings on the facility.

The ECB has expressed concern about Europe’s “addicted financial groups”. But with banks affected by their sovereign’s debt problems and maturing debt not being rolled over, the ECB has little option but to continue the arrangement.

The approach of the EU/ ECB assumed that the problem was temporary liquidity not solvency. The solution was to ensure that the troubled countries could continue to finance. The restoration of confidence would enable a rapid return to market financing and the status quo.

Nothing exemplified this better than the ill-conceived and poorly designed EFSF. Amongst the multiplicity of problems were the limited guarantees from Euro-zone countries and a reliance on CDO rating methodology. The preliminary analysis of the EFSF by the credit rating agencies confirmed the view that the facility was not designed for use. Close inspection also revealed that the facility was only capable of being drawn for an amount as low as Euro 250 billion, well short of the advertised Euro 750 billion. It was a pure confidence trick.

Irish Futures

As concerns about the underlying solvency of the countries continued, markets became increasingly nervous. The tensions focused around Ireland. While the problems of Ireland are well documented, the sequence of events was curious.

Ireland had sought “prime mover advantage” in austerity, reducing its budget deficits through severe cuts in government spending and tax increases. It established a state bank restructuring agency – National Asset Management Agency (“NAMA”) – to deal with bad loans made by banks. Ireland had completed its 2010 financing program, not expecting to come to market until early 2011. It also had Euro 20 billion in surplus cash.

A series of related events focused attention on Ireland. Bank bad debt problems re-emerged, especially at Anglo-Irish Bank. Forecast loan losses were revised upwards significantly, in turn increasing the demand on the state to finance the bailout of the banks. The cost, still unclear, was estimated at around Euro 50 billion (30% of Ireland’s GDP). This had the effect of pushing the 2010 Irish budget deficit to around 32% of GDP.

German Chancellor Angela Merkel raised the prospect of bondholders being forced to “share” losses in any debt restructuring. After a sharp increase in rates for many European countries in response to the suggestion, at the G-20 summit in Korea, European leaders clarified the proposal. It would only apply after 2013, when the current bailout arrangements expired. This drew attention to the temporary and short term nature of the EFSF and related support mechanisms.

Independently, Anglo Irish Bank offered to repurchase its outstanding subordinated debt for 20% of face value, warning that the return to investors in bankruptcy or restructuring would be far worse. This highlighted the risk of loss on Irish State or bank debt.

At the same time, Austria withheld its share of the due instalment of funds to Greece, arguing that key hurdles had not been met. While the Austrian posturing was mainly driven by domestic politics and funds were eventually released, the fragile nature of European support for the troubled borrowers was highlighted.

The parlous state of Ireland’s economy was unhelpful. The Irish economy shrank by 1.2% in the third quarter, a surprise to economic forecasters.

Markets pushed up yields on Irish debt inexorably. Higher rates caused losses on holdings of Irish bonds, triggering further selling. As rubber-necked accident voyeurs joined the party, the costs for Ireland to borrow commercially reached economically unsustainable levels closing access to financial markets. Depositors started shifting their money abroad, threatening a fully-fledged bank run.

They say if a politician denies that he is going to resign stridently often enough, he almost certainly will. Strenuous denials of the need for a bailout ended inevitably in one. A grim Irish Prime Minister Brian Cowen announced that Ireland would be receiving aid from the EU subject to meeting EU/ International Monetary Fund (“IMF”) conditions. It would, the Taioseach insisted, “secure Ireland’s future.” No one believed him.

Bailing Times

The Irish bailout facility totalled Euro 85 billion, made up of Euro 35 billion for the banking system (Euro 10 billion for immediate recapitalisation and Euro 25 billion to be provided on a contingency basis) and Euro 50 billion to cover the financing of the State. The average interest rate would be of the order of 5.8% per annum, depending upon the timing of the drawdown and market conditions.

After a brief rally, familiar concerns re-appeared. Estimates suggested that the Irish banks alone required around Euro 16 billion in capital and a further Euro 38 billion in financing. This totalled Euro 54 billion, 64% of the Euro 85 billion package. Given that Ireland required Euro 70 billion to meet maturing debt until 2013, the size of the bailout facility was arguably inadequate. As in the case of Greece, the bailout package dealt only with short-term liquidity, failing to address Ireland’s longer term solvency.

The arrival of an IMF/ EU team to prescribe a “cure” did not inject the expected confidence in an imminent recovery. Ireland had been self administering the same medicine for some time, with indifferent results.

The Irish economy has not recovered from recession, with GDP only registering growth in one quarter since 2007. Overall, the economy has shrunk by nearly 20% from its peak. Gross National Product (“GNP”), which is a better indicator of living standards, has fallen for nine successive quarters. The official unemployment rate is around 14%, though the level of real unemployment and under employment is greater. House prices are 36% below their 2006 level. Consumer spending has fallen sharply, the result of lower income and increased savings levels of around 12% of income (an increase from 3.9% two years ago).

Cuts in government spending and higher taxes have mired the economy in recession. Falls in tax revenue necessitate increasingly deeper cuts in spending to try to stabilise public finances. In 2010, the budget deficit was forecast at 12% of GDP, even after spending cuts and tax rises worth Euro 14.5 billion

The problems of the banking sector are increasing due to the poor economic conditions. Hitherto largely confined to commercial property, problems are now spreading to the broader economy. Unemployment and lower incomes mean that householders are unable to meet payment obligations on mortgages and other loans. Weak economic conditions have affected businesses, increasing default levels.

Following the bailout, the Irish government announced further cuts in the budget deficit of Euro 15 billion, with Euro 6 billion scheduled for 2011. The package included Euro 10 billion of spending cuts covering social welfare, health care, education and the public sector. There were Euro 5 billion of tax increases, including increases in value added tax (VAT), income taxes and property taxes. Controversially, the low 12.5% corporate tax rate, crucial to maintaining Ireland’s competitive position, remained unchanged, despite complaints and pressure from the EU.

The ability to meet the required targets is uncertain. Forecasts are predicated on “aspirational” growth of 2-3%. Moody’s Investor Services, the rating agency, cut Ireland’s debt rating by five notches Baa1, two notches above junk, with a negative outlook.

The experience of Greece under the IMF/ EU plan is instructive. While there has been some progress, Greece is struggling to meet its budget targets due to a shortfall in tax revenues, forcing ever more aggressive spending cuts exacerbating Greece’s deep recession. Planned asset sales and structural reforms are unlikely to stabilise public finances. Faced with the unpalatable choice of withholding funding due to non-compliance with the plan or allowing default, the EU/ IMF have continued to disburse funds propping up the economy. The maturity of the bailout package is likely to be extended, acknowledging that it cannot be repaid.

In the absence of strong economic growth, inflation and a massive devaluation, the peripheral economies, such as Ireland and Greece, may be unable to shrink themselves to solvency.

A simple relationship demonstrates the unsustainable position:

Changes In Government Debt = Budget Deficit + [(Interest Rate – GDP Growth) X Debt]

In order to restore solvency, overburdened borrowers must stabilise debt and begin to reduce the level of borrowing. This requires GDP Growth exceeding interest rates, a budget surplus (through spending cuts and/or tax cuts) or a combination of these.

EU/ IMF assistance to Ireland was designed to address the high yields on Irish bonds, which curtailed the State’s ability to borrow. But the 5.80% cost of the bailout debt requires an equivalent growth rate and a balanced budget simply to stabilise debt at current very high levels.

Based on the IMF’s best estimates, there is little prospect of many European countries returning to balanced budgets any time soon. Given the toxic conjunction of high cost of funding, low growth and high starting level of debt, it is near impossible for these countries to contain the spiral to a restructuring of their debt or default.

When asked for directions, the old joke is that some wise guy pipes up: “If you want to go there, then I wouldn’t start from here.” The same could be said of rescuing overburdened European countries.

The perennial question: as the problem cannot be solved (at least not while the euro is overvalued some 40% above survival fitness), would not be a lot better for European governments to simply declare bankruptcy (pass the ball to whoever is the creditor) and start financing themselves without credit (i.e. out of taxes only), at least for a decade or so?

No need to collapse the euro or anything valuable like social services, just pass the ball to creditors and start living on real means (taxes).

This is bad for big banks all around the World but these are rotten to the marrow and will anyhow collapse sooner than later, so who cares?! The only relevant thing is that citizens are delivered to according to reasonable expectations, right? That’s what states are there for according to my basic understanding of democracy: for the public good.

Although this article is unabashedly pro-banker, it nevertheless does provide an excellent anecdotal example of the choice facing policy makers.

The San Francisco Bay city of Vallejo filed for Chapter 9 bankruptcy in 2008 as a result of insolvency. The choice confronting city leadership then became one of which contractual obligation to meet: that to bankers and bondholders, or that to retired former city employees. The Vallejo city leadership, much to the chagrin of the Barron’s writers, evidently came down on the side of pensioners:

The California municipality, which has 120,000 residents, is proposing a three-year moratorium on all interest and principal payments on the $53 million of municipal debt that is backed by its general fund. But it is keeping fully intact its $84 million in pension-fund obligations.

Current non-contractual obligations to the citizens to deliver ongoing services also get caught up in the mix.

Unfortunately it looks like policymakers in Greece and Ireland have decided to go just the opposite direction as those in Vallejo did. Bankers and bondholders must be paid, and pensioners and public services be damned.

This also explains the full court press by the bankers’ propagandists to demonize not just public employees of California, but the entire state of California.

You see the same dynamic in Europe, where the bankers’ propagandists target not just the public employees of Ireland and Greece, but the entire countries.

Bailouts? Not really. The liquidity is supplied to give the time necessary to dispossess the people of title to property. This is alchemy. Alchemists exchanged lead for gold by convincing the people that they had some magic talent that the people did not have. Central banks change “little units of fraud”, vortex money, for title to real property. It takes a process, but it is exchanging the sham for the real. Exchanging the sham for the real is the objective of alchemy.

Pretty nifty business model. The big cahunas rather than support society through taxes gets society to borrow the funds and little joe pays the taxes and interest.

Why did you have to comment in such a manner.

Now I can only envision this hole affair as a decades long ROFIE credit high, only to wake up with a sore you know what, yet the Perps are laughing their back sides off watching their latest video upload on the securitization porn channel.

Skippy…curse you!

So when does the “Wily E. Coyote” moment arrive?

Just watched some of those old cartoons on YouTube. Now THAT is talent!

Far more than the sweaty armpit money-lust math madness Bankster Bozo Bull-sheeet. LOL. YOu dumb shallow crackhead$.

I have a question on the formula you cited for change in debt:

Changes In Government Debt = Budget Deficit + [(Interest Rate – GDP Growth) X Debt]

I think that GDP growth feeds in to the ability of the government to pay back the debt and is thereby accounted for in the budget deficit (or surplus) part of the equation. If you are referring to the real value of the debt, you need to factor in inflation (a further question is what type of inflation exactly – CPI wont be suitable I guess). If you factor in inflation, I think the equation will be

Changes to real govt debt = Budget deficit + (interest rate – inflation rate) * Debt

Suggestions?

‘[Stabilizing debt] requires GDP growth exceeding interest rates, a budget surplus (through spending cuts and/or tax cuts) or a combination of these.’

In this equation, GDP growth is raw, nominal GDP growth — that is, before the GDP deflator is applied. Most news reports cite real GDP, so one has to consult the tables in the report to find the nominal figure.

In the U.S., for instance, nominal GDP was growing at 4.46% in the 12 months ending in the third quarter of 2010, while the yield on the 10-year T-note is 3.32%. Thus the U.S. economy is outgrowing its nominal financing cost by 1.14%.

By contrast, last July the IMF projected Ireland’s nominal GDP would shrink 2.6 percent in 2010 … suggesting that the Irish economy is delivering a negative return of 8.4 percent on bailout package borrowing at 5.8%.

http://www.irisheconomy.ie/index.php/tag/irish-gdp/

A negative return of 8.4 percent, compounded for any length of time, will sink any entity on earth.

By the way, ‘tax cuts’ should be ‘tax hikes’ in the quoted sentence (first paragraph above).

And strictly speaking, I believe the equation refers to ‘stabilizing the debt-to-GDP ratio.’

This week is Portugal’s turn in the spotlight:

http://noir.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601087&sid=a0cELxb0jgPY&pos=1

Portugal has said that bond yields over 7 percent are unsustainable. And there they are, holding at ‘unsustainable’ levels even with official support.

Bond auctions this week will tell the tale. I’d say chances are about 50-50 of a white-knuckled crisis weekend, with a rescue package for Portugal being announced Sunday night, in much the same fashion that the Irish bailout was.

Of course, as Satyajit Das says, it’s only a tactic to buy time. Greece, Ireland, Portugal, and perhaps even Belgium CANNOT grow their way out of the debt traps they’ve fallen into. Restructure now, or restructure later and larger.

The ability of the zombie economics to go on, despite the obvious evidence against it is amazing. The bailouts of Greece, Ireland, and Portugal are not actual bailouts of the countries, but rather bailouts of the bondholders of private banks in those countries that had engaged in Ponzi finance. Meanwhile the Government spending is cut, which surprise, leads to slower economic growth, which leads to lower tax revenue, which leads to a bigger deficit, and the need for more cuts! And because the political elites have such an ego investiment in the Euro project, leaving the Euro, the one thing that could spur economic growth based on export demand, is an option beyond the pale.

Of course this is now the same course, with a “strong dollar,” being recommended for the U.S.

It is a foregone conclusion that Ireland and Greece will not be able to pay back ECB/ESFS/IMF. These plans were to buy time and kicked the can down the road.

The scary argument that Satyajit states is that there was only 250 Billion Euro’s available for drawdown in the ESFS alleged 750 Billion Euro rescue plan.

Heretofore the ESFS fund would not have enough money for Spain. It is now questionable if there is money for the much smaller Portugal. And no additional money for Ireland or Greece.

The sharks are circling Portugal, Belgium, Spain and even France. At best all see significantly higher rates. More importantly Angela Merkel will see a complete loss of confidence in bailing out everyone else.

This has an ugly ending. The Euro eventually becomes a smaller group of countries. The banks take major losses. The Euro markets get hammered.

The ESMF and ECB loans get haircuted. And Soveriegn defaults are the only answer for Greece and Ireland as they go through citizen revolts including throwing out their existing governors.

Eventually bond markets will realize corporate debt is better than government debt because there is actual collateral or that the debt can be exchanged for equity.

Even the QE2 the dollar strenghtens significantly to 1.20 and eventually parity.

{Article read}

{Computing data}

{Activating high level heuristics}

{Creating response…please wait!}

{calibrate sarcasm level…set to HIGH}

{Begin rant}

By now, it should be plenty obvious that solvency crisis MANDATES a significant haircut to lenders, who, BTW, were not forced by ANYONE to lend to countries. It’s call capital at risk, which presume that in case of poor decision making and/or bad risk management, the laws of raw capitalism will invoke the spirits of Professor Pain, which, in turn, will be very happy to teach his proverbial lessons to those whose imprudence or recklessness has selected to get an deep immersion course.

But nooooo! Banksters are powerful, they’ve got the dinero, this elixir of political survival and growth, hence, the natural laws cannot apply to them now, can’t they?

It is so much easier and obvious to heap scorn and despise on the masses who deserve everything coming at them: I mean, consider the following: the impudent REMFs do not want to give money to the politics. Moreover, these asshats believe that, just because they pay taxes, they have the right to RECEIVE services…Goodness gracious! Perish the thought! They are obviously sick in the head: must be this virus called “democracy” that got to their already very feeble reasoning capacity.

Thankfully, the powers that be are on the side of those who matter the most.

What a relief!!

{end of rant}

The analysis in this article is pretty much spot on, except the author must remember that it is not the current financing rate which must be considered, but the historical financing rate. Ie 5.8% is not the figure which must be factored into the “debt-stablization equation”, but the weighted average of debt financing rates at the time of each respective issue (unforunately I do not have this figure).

The latter will no doubt trend towards the former, but the distinction between the two is of utmost importance when conducting analysis of this variety.

Diversion. All of it.

Denmark has the second-largest bailout package of all of the EU, despite being the smallest country, yet never discussed because “we are not part of the Eurozone”.

There is about 6 years of total taxes on the line here and the government has probably already received their first DKK 100 billion margin call of several: The government has proposed and carried out serious reductions in unemployment benefits, student grants, increased the retirement age and proposed to cut a previously most-sacred early retirement scheme. This just before a general election. The “opposition” being very, very silent too.

The Danish news media are totally busying themselves with “Happii-news” about the imminent “recovery” and trivia while everyone I know are either sacked or see repeating rounds of cleansing.

This is getting scary. I have set up some savings in SEK and CHF in case a speedy exit becomes necessary. One can live a long time on a little money in Sweden – unlike Here (probably why the Swedes are whupping our arses yet again).

The Danish Krone is “bound” to the EU via central-bank intervention; This kind of pegging a small currency to a much larger one has “never” blown up before, obviously ;-)

“””

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aI.TvvSBYXBM

Bank Rescue Costs EU States $5.3 Trillion, More Than German GDP

Following is a table of European government’s commitments. All figures are in billions of euros and include capital injections, guarantees granted, effective asset relief and liquidity interventions.

United Kingdom 781.2

Denmark 593.9

Germany 554.2

Ireland 384.5

France 350.1

Belgium 264.5

Netherlands 246.1

Austria 165

Sweden 142

Spain 130

To contact the reporter on this story: Meera Louis in Brussels at mlouis1@bloomberg.net

“””

That’s very very interesting and, as you say, almost totally unknown. Thanks for the info, Fajensen.

It is also very interesting to see how only Ireland among the so-called PIIGS states, has a sizable bailout, with the major bailouts being actually in the wealthy states, often totally out of proportion with their demographic or even GDP or budget figures.