Yves here. I thought this post was useful not only in describing how high food prices posed a particularly difficult policy problem for North African countries, but also in providing important background.

By Ronald Albers and Marga Peeters; cross posted from VoxEU.

World food prices are now even higher than their peak just before the global crisis. During periods of high commodity prices, North African and Middle Eastern governments have a long tradition of subsidising food and fuel products. But this column shows that food price inflation and consequently subsidies were also high during periods when global commodity prices were falling. Now these countries have an opportunity to correct this.

Just before the global crisis struck in September 2008, food and fuel prices soared, pushing up inflation in most countries (see for example, Tangermann 2008 and Conceição and Mendoza 2009 on this site). The impact was particularly large in North Africa and the Middle East (such as Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt, Israel, Jordan, Palestinian territories and Syria) where food constitutes a large share of consumer spending. Only those countries with more developed agricultural sector, such as Morocco, escaped to some extent from a rise in its consumer price inflation due to the available domestic supply of basic commodities.

In 2009, the global crisis reduced the global demand for food and fuel and subsequently stopped the surge in global commodity prices. On its own, this lower inflation was a welcome blessing, notably in countries such as Egypt where annual consumer price inflation had reached 24% in August 2008.

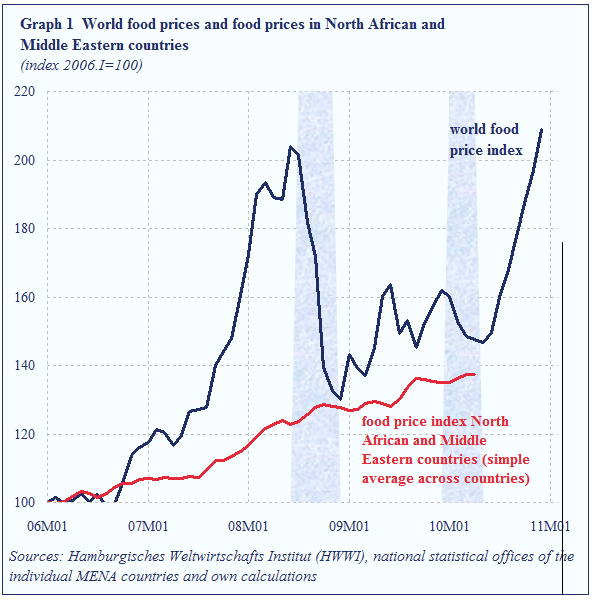

Figure 1. World food prices vs. North African and Middle Eastern food prices

The impact of the soaring commodity prices on public finances

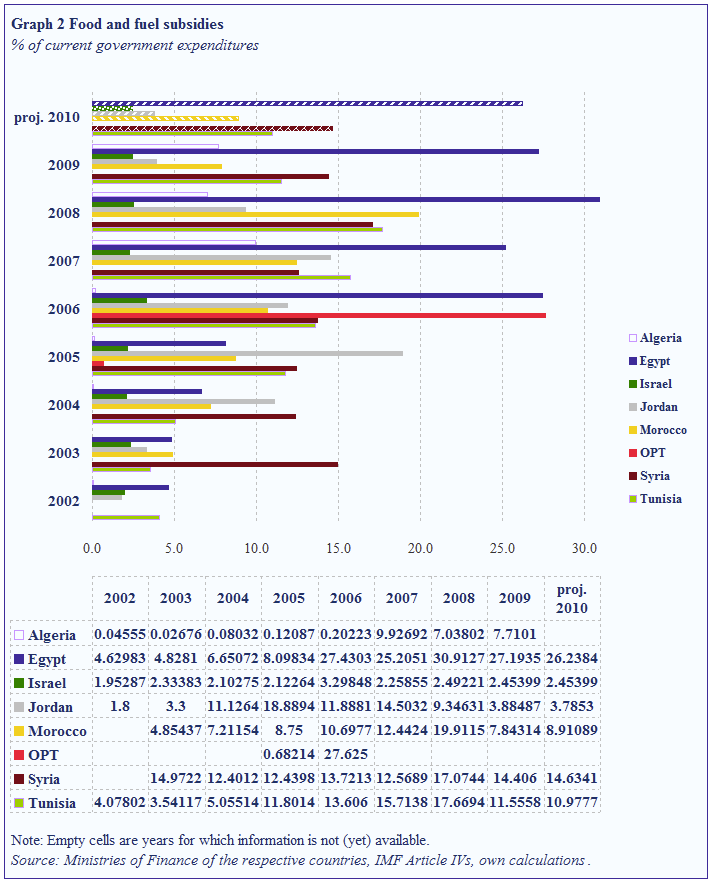

Governments in North African countries have a long tradition in subsidising food and fuel – and higher prices have led to higher spending. Across these countries, the impact of the subsidies on the fiscal balances varies but subsidies take up at least 10% of current government expenditures in most countries (see Albers and Peeters 2011, and Figure 2).

Figure 2. Food and fuel prices (click to enlarge)

The dilemma for policymakers and possible ways out

Cutting down these subsidies, particularly for food, is extremely difficult for governments. The recent (successful) revolts by the public in Northern African countries, but also earlier revolts that took place at a smaller scale just before the global crisis, show the pressure on the North African and Middle Eastern governments. Reforming the subsidy system on food would add to the unrest.

Reforms in food subsidy systems directly imply that the basic necessities will become more expensive, which would disproportionally affect the poorest families. In addition, from a macroeconomic perspective, consumer price inflation that has already been high for many years would rise even more. Cutting subsidies implies higher final consumer prices and this would immediately make it harder for the monetary authorities to achieve price stability. The fiscal and monetary authorities therefore face a dilemma:

Not cutting subsidies implies that their fiscal balances remain in a bad shape.

Cutting subsidies deteriorates the purchasing power of consumers, where the poorest will be disproportionally affected

Between the two extremes of cutting and not cutting subsidies, there are however intermediate solutions. One solution is to phase out subsidies gradually, which is already high on the reform agenda in some countries (Jordan and Egypt). This gives the fiscal authorities gradually more room to manoeuvre in their choices for fiscal spending and consumers and monetary authorities can also gradually adjust to the new prices. Alternatively, a solution lies in a more precise system of targeting subsidies in such a way that only the people that are in need of the subsidies receive them (a policy that, among others, Egypt started). This measure is not easy to implement as family income needs to be determined and a cut-off line needs to be drawn. But if this policy can be implemented, two important objectives would be achieved:

I

t would help improve fiscal balances by creating more room for manoeuvring on discretionary spending, and

it would not hit the poorest consumers.

Downward price rigidities

In line with the reasoning that higher food prices push up consumer price inflation —all things being equal, lower food prices should depress inflation. But during the global crisis world food prices dropped while food price inflation remained high in North African and Middle Eastern economies (see the light blue areas in Figure 1 that indicate long periods of falling world food prices). In most countries around the world, food prices at the national levels fell in this period and consumer price inflation at the national levels came significantly down accordingly. This lower inflation gave room for monetary authorities to loosen monetary policy, which stimulated the real economies helping them to recover from the Great Recession.

Yet, as shown, inflation came down only little in the North African and Middle Eastern economies (see also Peeters and Strahilov 2008). This is puzzling. Apparently there are factors that prevent domestic food prices from dropping. These downward rigidities can come from several domestic sources that must lie in the domestic food production and distribution chain that starts at the point where basic food products are imported at a country’s borders until the point where the finished food product is sold to the consumers.

The collective governmental organisation of importing basic food products at the world markets or monopolistic behaviour, price speculation on the scarce products at the domestic market, or (superfluous) intermediaries in the food chain must have been impacting food prices and driving them up, despite the sharp drops of prices at the world markets.

If domestic food prices are not only pushed upwardly by positive world price shocks, but also domestically by non-functioning markets, the fiscal authorities need to not only seek the solution for reforming the subsidy system to achieve lower subsidy spending in phasing-out subsidies or direct targeting of subsidies. Policy actions should also be taken to allow a better functioning of the markets, such as the breaking down of (government) monopolies, reducing the food supply chain, stimulating more competition in the private market to import and trade in agri-food and the food distribution business.

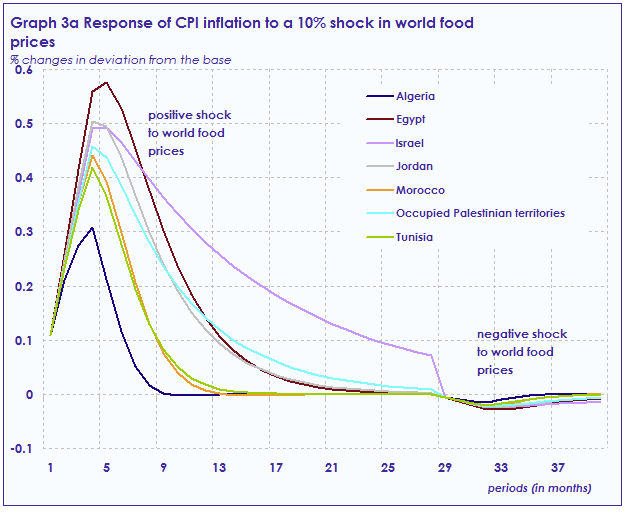

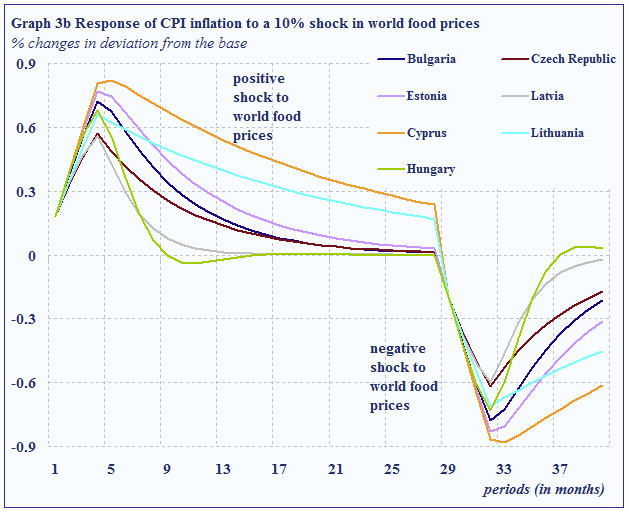

Econometrically, the existence of the downward rigidities in food inflation follows directly from inflation regressions. Consumer price inflation is explained by, among others, world food inflation split into decreases and increases in annual world food inflation. It follows that negative world price changes are insignificant in North African and Middle Eastern countries. This implies that inflation does not go down in case world food prices drop. In order to show the contrast with other countries, this analysis is also performed for a similar size group of most recently acceded EU countries. The results of this analysis show that negative adjustments in world food prices significantly depress inflation in these countries. Thus, inflation easily goes up but hardly goes down in North African and Middle Eastern countries while in other countries inflation drops in response to negative shocks. Our simulation (Figure 3) illustrate this point based on our econometric results.

Figure 3a. Response of CPI inflation to a 10% shock in world food prices

Figure 3b. Response of CPI inflation to a 10% shock in world food prices

Opportunity for change

Apart from the non-functioning domestic food markets, another relevant point is the policy reaction of some governments to the soaring consumer price inflation. Instead of tackling the main causes for the high food prices, wages were regularly raised in the public sector in order to compensate government employees for the loss in purchasing power (notably, this happened in Egypt and Jordan). This not only creates an even sharper difference between the public and private sectors than the already existing big difference. It also fuels inefficiencies and monopoly keeping in the food supply chain that is by and large part of the public sector. Moreover, raising wages in the government sector can accelerate a price-wage spiral. Wages should not be raised in response to higher inflation. Taking policy measure to achieve a well-functioning of the domestic food supply chain according to market standards is the highest priority.

The current political changes in the south Mediterranean region offer an opportunity to take these type of reform measures.

Sadly, there is also so much politics involved in this horrible equation. Everything from the internal politics of the subject country (if the public service and the military have better access to food thy are more loyal), to the political realities in producer countries, where production/or non production, is often subsidized. Thus causing imbalances in the global supplies.

Even global demands for ‘exotic’ crops can be disruptive of food supplies and prices. Crops like; bannanas, coffee, sugar, pinnapple, cotton, and even heroin/opium, all displace traditional food crops and contibute to the problem.

Possibly this is puzzling to the authors because of their nationalities,

“Yet, as shown, inflation came down only little in the North African and Middle Eastern economies (see also Peeters and Strahilov 2008). This is puzzling. Apparently there are factors that prevent domestic food prices from dropping.”

The people of Nort Africa generally live in a different reality than Western minds can comprehend. Considering both very low percapita incomes for most people and a situation where most people cannot grow food, any available money is spent on food at hatever price. The only difference is that low prices mean full bellies. It may have been unfortunate that the authors chose European countries for a comparison.

To try explain what I mean(sorry to be tedious). One might compare North Africa’s food situation with the petroleum situation in Europe. There is little price elasticity for oil in most of Europe because supplies are limited, but the functioning of their modern economies requires oil.

Maybe the inelasticity is a by-product of the subsidies. Since the subsidized prices were already below world market, falling market prices meant that governments had to spend less on the subsidies. But the consumer price would have remained more stable than the world price. That’s what the subsidy is for, no?

“Yet, as shown, inflation came down only little in the North African and Middle Eastern economies (see also Peeters and Strahilov 2008). This is puzzling.”

Or perhaps it’s sort of obvious in that the first world eats better than it needs to, and can therefore substitute for cheaper foods when it needs to. Those who already eat those cheaper foods can not substitute, and therefore experience inflation as the prices for the cheapest goods rise.

“Spengler” at Asia Times on line has interesting things to say about events in Egypt.

Not cutting subsidies implies that their fiscal balances remain in a bad shape.

Cutting subsidies deteriorates the purchasing power of consumers, where the poorest will be disproportionally affected

———————–||

Well, chosing between a balanced budget and people dieing of hunger is really a tough call. Which one is more economical? Gee.

Well put.

Personally, I prefer the more MMT/New Keynes articles to the neoliberalism.

Also… I think most of us have been inspired and impressed with the recent protests in Egypt, and considering the importance of food subsidies to protests in Egypt over the last 50 years, this post strikes me as intellectually out of touch.

An interesting post, but surely you are over-thinking it?

Bottom line: 100 million more people each year. No more arable land or fresh water. Crop yields/acre have been flat for over a decade – and are set to fall as farmers plant marginal land. There will be wild swings up and down due to weather and financial speculation etc., but what’s driving the long-term trend is the basics of supply and demand.

It should be noted that rapid population growth is often created by government policy, in order to keep wages low and profits high. The rich make a quick buck, but the long-term prospect of forced population growth has always been this sort of chaos. Pity we can’t talk about this.

Yes.

To further extrapolate: 40% of Washington state’s wheat crop last year was sold to Egypt. In June 2008, a US Senate subcommittee held a hearing on commodities speculation. Among those testifying were Michael Greenberger, George Soros, and a gentleman from a small town in the center of Washington state, right smack in the middle of a large ag region. His concerns about energy speculation? All those farmers use petroleum based commodities for their combines, as do the food distribution systems.

So taking a few steps back from the problems in N. Africa, this whole issue of commodities speculation, food supplies, and productivity is a huge global issue with a myriad off unremarked-upon interconnections.

Thanks for keeping this complicated issue of ag production and food supplies before the public eye, Yves. And I type that with deepest gratitude.

Debt is an efficient tool. It ensures access to other peoples’ raw materials and infrastructure on the cheapest possible terms. Dozens of countries must compete for shrinking export markets and can export only a limited range of products because of Northern protectionism and their lack of cash to invest in diversification. Market saturation ensues, reducing exporters’ income to a bare minimum while the North enjoys huge savings. The IMF cannot seem to understand that investing in … [a] healthy, well-fed, literate population … is the most intelligent economic choice a country can make.

— Susan George, A Fate Worse Than Debt, (New York: Grove Weidenfeld, 1990), pp. 143, 187, 235

This seemingly and ostensibly well-intentioned article is concerned about well being MENA population and “theirs” government subsides as opposed to “ours” government subsidies. One can find hundreds of articles on the internet if you search: EU Common Agricultural Policy – subsides which amount to >$300 billions and US too. Our subsidies are in function of development, their subsidies are against “free trade” and WTO rules. It is easy to see that this type of articles coming from neo-liberal and IMF/WB/EBRD phalanges of so-called economists.

“One solution is to phase out subsidies gradually, which is already high on the reform agenda in some countries (Jordan and Egypt). This gives the fiscal authorities gradually more room to manoeuvre in their choices for fiscal spending and consumers and monetary authorities can also gradually adjust to the new prices.”

Wow, what prescription. One of the Egypt’s biggest retail food chain is French Carefour, and Egypt is the world largest importer of (US) wheat; armament too. The textile factories which combed world famous Egyptian cotton are foreign owned. So, the question is: whose benefits they are talking about here? How to explain the fact that Libya with oil export of $70 billion is having 30% unemployment, crumbling infrastructure, high illiteracy and what not. French truck drivers and farmers would have set the France on fire if “their” government just try to cut subsidies. Primordial question of imperial man “as” vs. “them”.

Last night I was watching The Inside Job, while it was bellow of my expectation, it was funny watching people from the field called “economy” and their explanations and the face expressions. With myriad prefixes in front of their names and protected with institutions (Harvard, Columbia, Stanford and what not) where they are working “the high priests” dominate media space. By the way, I got impression that academia elite and politicians had a lot of fun during the filming. The same case is here with those two so-called economists. They probably worked for and with, notorious Pascal Lammy. By reading their bios, I can not notice their academic accomplishment. One of them was in Albania and that country is another case in point of Washington Consensus policy, meaning notoriously weak and unstable. The lecture is well know from history, Tacitus: “They made a desert and they called it peace”.

All sarcasm is intended.

The basic calculus of ending food subsidies in the MENA region is to either raise family incomes up to a level where they can afford to buy at non-subsidized prices or let those who cannot afford food to simply die off. Any combination of these two approaches works as well.

Neither of these two things is likely to happen anytime soon. It is interesting that Iraq is not mentioned in the article since they have been experimenting with ways to dismantle their Saddam-era food subsidies. The last I heard was that these liberalization experiments had failed and that they were quietly returning to the policies from the Nineties.

Since MENA has oil, in theory at least, it seems logical that in the most simple sense that oil would be traded for food. The increased price of oil is driving the increase in food prices so the MENA region as a whole is well hedged for fluctuations. As the various governments’ oil revenues go up, their food subsidies will go up as well. The problem is the patchwork map of the MENA regions where many countries have lost out in the oil lottery. The recent and ongoing Arab Spring revolutions may help resolve this problem as a larger Sunni Arab political unit starts to become possible. In very general terms the oil-rich countries tend to have weak militaries while the oil-poor countries have relatively powerful armed forces. For example how long will militarily powerful Egypt allow Gaddafi to unleash his sub-Saharan African mercenary goons on an largely unarmed Arab population? The reward for moving in and delivering a coup de grace to the Gaddafi insanity could be a percentage of the revenue stream from Libyan oil and natural gas for Egypt. In any case, as these revolutions play out, there may be an EU-style enlargement of the MENA political architecture (sometimes also referred to as a caliphate) that could help stamp out the concentrations of oil wealth in the Arab world and lead to a mid-term run of relative prosperity.

Once the oil is all gone though, of course, all bets are off. These areas are deserts after all and their ability to sustain human life is limited. For even with the current food subsidies people are still dying of starvation. When I was in Agadir (Morocco) several years ago one person I visited there told me that because of a recent dry spell, children were starving to death in the various shanty towns. I saw urban peasants walking their emasculated goats on the various dusty and dry center-divides of large boulevards searching for any bit of weed to eat so that the goat could give milk. And just a few blocks away from these scenes of desperation was the splendid Royal Palace with its opulent gardens. Of course there were huge gates and a spiked fence to keep those goats from grazing on the greenery there.

The ongoing revolutions will need to even out these huge disparities of wealth on both the local scale as well as among the various nations or the fate of the MENA region will be strife and starvation and eventually a much reduced population.

“YESMEN” have their “McDonald’s Solution”…