By Michael Kumhof, Deputy Division Chief, Modeling Unit, Research Department, IMF and Romain Rancière, Associate Professor of Economics at Paris School of Economics. Cross posted from VoxEU

Of the many origins of the global crisis, one that has received comparatively little attention is income inequality. This column provides a theoretical framework for understanding the connection between inequality, leverage and financial crises. It shows how rising inequality in a climate of rising consumption can lead poorer households to increase their leverage, thereby making a crisis more likely.

The US has experienced two major economic crises during the last century – 1929 and 2008. There is an ongoing debate as to whether both crises share similar origins and features (Eichengreen and O’Rourke 2010). Reinhart and Rogoff (2009) provide and even broader comparison.

One issue that has not attracted much attention is the impact of inequality on the likelihood of crises. In recent work (Kumhof and Ranciere 2010) we focus on two remarkable similarities between the two pre-crisis eras. Both were characterised by a sharp increase in income inequality, and by a similarly sharp increase in household debt leverage. We also propose a theoretical explanation for the linkage between income inequality, high and growing debt leverage, financial fragility, and ultimately financial crises.

Diverging incomes, rising debt

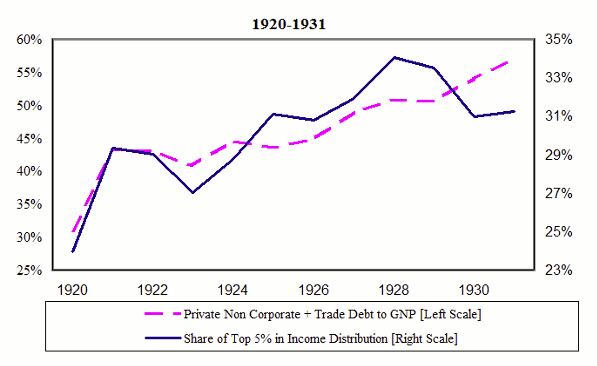

Figure 1 plots the evolution of the share of total income commanded by the top 5% of households (ranked by income) against household debt to GNP or GDP ratios in the two decades preceding 1929 and 2008. The income share of the top 5% increased from 24% in 1920 to 34% in 1928, and from 22% in 1983 to 34% in 2007. During the same two periods, the ratio of household debt to GNP or to GDP increased dramatically. It almost doubled between 1920 and 1932, and also between 1983 and 2008, when it reached much higher levels than in 1932.

Figure 1. Income Inequality and Household Leverage

In standard models, a persistent increase in the dispersion of income should be associated with a similar increase in the dispersion of consumption levels. However the data show that the increase in the dispersion of consumption levels over the last 25 years has been much more moderate. This implies that poor and middle-class households must have become more indebted, while rich households became less indebted.

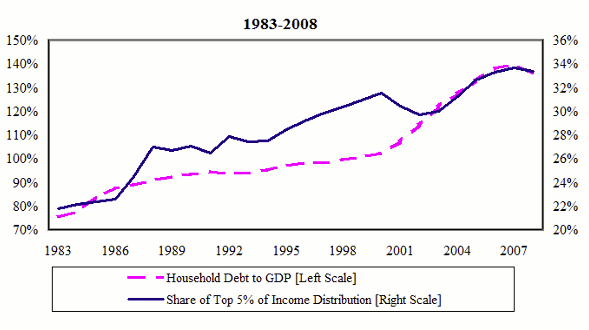

Figure 2 plots the evolution of debt to income ratios for different income groups. In 1983, the top 5% exhibited a debt to income ratio of 80% and the bottom 95% a ratio of 60%. Twenty five years later, the situation is dramatically reversed with a ratio of 65% for the top 5% and of 140% for the bottom 95%.

Figure 2. Debt-to-income ratios

Borrowing and higher debt leverage appears to have helped the poor and the middle-class to cope with the erosion of their relative income position by borrowing to maintain higher living standards. Meanwhile, the rich accumulated more and more assets and in particular invested in assets backed by loans to the poor and the middle class. The consequence of having a lower increase in consumption inequality compared to income inequality has therefore been a higher wealth inequality.

The increase in debt leverage of the bottom group of the distribution has implications for both the size of the US financial industry and its vulnerability to financial crises. The increase in the reliance on debt for the bottom group and the increase in wealth of the top group generated a higher demand for financial intermediation. Between 1981 and 2008, the US financial sector grew rapidly, with the ratio of private credit to GDP more than doubling from 90% to 210%.

The share of the financial industry in GDP doubled as well, from 4% to 8%. As borrowers’ debt leverage increases, the economy becomes gradually more vulnerable to the risk of financial crises. When a crisis eventually materialised in the fall of 2008, it was accompanied by a generalised wave of defaults, with 10% of mortgage loans becoming delinquent, and a sharp output contraction.

The link between inequality, debt, and crises

The link between income inequality, household debt leverage, and crises has recently also been discussed in the books of Rajan (2010) and Reich (2010). But these authors do not make a formal case to support their argument. This matters because there is a debate as to whether high debt levels were primarily driven by the demand for credit, as in Rajan (2010), or by the supply of credit, as in Levitin and Wachter (2010).

In our work, a general equilibrium model allows us to reconcile both views, by way of a shock that simultaneously increases the supply and demand of credit. Our model has several novel features that are motivated by the stylised facts above.

First, households are divided into a top 5% income group that derives all of its income from returns on its ownership of the economy’s capital stock and from interest on loans, while the remaining 95% earn income through wage labour. We refer to these groups as investors and workers.

Second, consumption preferences are characterised by a subsistence consumption level that makes households resist very large drops in consumption.

Third, wages are determined by a bilateral bargaining process between investors and workers that is subject to persistent shocks.

Fourth, following the “capitalist spirit” specification of Carroll (2000), investors have preferences not just over consumption, but also over the ownership of physical capital and financial assets.1 This implies that investors will allocate any increase in income gained at the expense of workers to a combination of higher consumption, higher physical investment, and higher financial investment. The latter consists of increased loans back to workers, thereby allowing the latter to continue to maintain sufficient consumption levels to support the economy’s production.

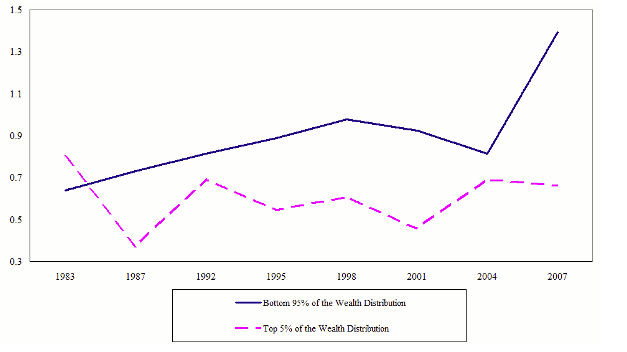

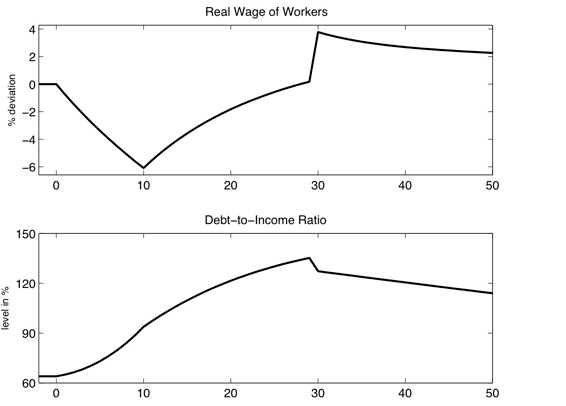

The baseline results are shown in Figure 3. The horizontal axis represents time, with the shock hitting in year 1 and the final period shown being year 50. A slow-reversing shock to the distribution of incomes in favour of investors generates a gradual increase of the debt-to-income ratio of the bottom group.

Figure 3. Baseline results

In our closed economy set-up, the increase in leverage of the bottom 95% is made possible by the re-lending of the increased disposable incomes of the top 5% to the bottom 95%, resulting in consumption inequality increasing significantly less than income inequality. Saving and borrowing patterns of both groups create an increased need for financial services and intermediation. As a consequence the size of the financial sector increases. The rise of poor and middle income household debt leverage generates financial fragility and a higher probability of financial crises. With workers’ bargaining power, and therefore their ability to service and repay loans, only recovering very gradually, the increase in loans and therefore in crisis risk is extremely persistent.

In our model, a crisis materialises in period 30. It is characterised by large-scale household debt defaults on 10% of the existing loan stock, accompanied by an abrupt output contraction as in the 2007-2008 US financial crisis, which is modelled as a destruction of physical capital.

The crisis barely improves workers’ situation however. While their loans drop by 10% due to default, their wage also drops significantly due to the collapse of the real economy, and furthermore the real interest rate on the remaining debt shoots up to raise debt servicing costs. As a result their leverage ratio barely moves, and it in fact increases further later on so that by year 50 it is above its pre-crisis level, with a very slow reduction thereafter.

A number of factors could make the increase in leverage even worse.

First, if capital owners allocate most of their additional income to consumption and financial investment rather than to productive investment, leverage increases much more because workers’ income does not benefit from a higher capital stock.

Second, if the rate at which workers’ bargaining power recovers is even slower than in the baseline, then even a financial crisis with substantial loan defaults of 10% of all outstanding loans provides little relief, with leverage continuing to increase for decades post-crisis, and making repeated financial crises very likely.

Third, if the subsistence level of consumption is significantly higher than in the baseline, households borrow more aggressively to avoid what they perceive as a catastrophic drop in consumption.

A chance of success

There are, however, two possibilities for a successful deleveraging of households.

The first is an orderly debt reduction that is not accompanied by a large real crisis. This can be shown to reduce leverage much more powerfully than in the baseline because debt reduction is not accompanied by a significant income reduction. But, for an unchanged pattern of bargaining power, a trend towards higher leverage resumes after the debt reduction, and only reverses much later.

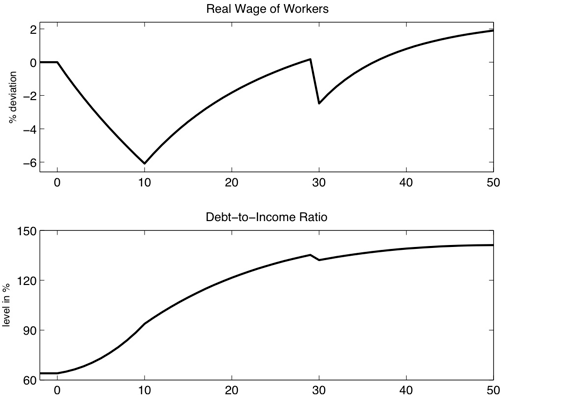

The second possibility, which is illustrated in Figure 4, is a restoration of workers’ bargaining power and therefore income that allows them to work their way out of debt over time. Leverage drops immediately, but due to a higher income level rather than a reduced loan stock. More importantly, and unlike under a debt reduction, leverage goes onto a declining path that immediately starts to reduce the probability of a further crisis.

Figure 4. Restoring workers’ bargaining power

This line of research could be extended to an open economy setting. An increase in lending by high income households would then extend not just to domestic poor and middle income households, but also to foreign households. The counterpart of this capital-account surplus in the foreign country would of course be a current-account deficit. In other words, this approach provides a potential mechanism to explain global current-account imbalances triggered by increasing income inequality in surplus countries.

I am sure there is a correlation between inequality and financial crises. Also between stagnant working incomes, increased household debt, and subsequent financial crises.

The question is, causation. The implication of some accounts of this is, don’t worry about the money supply or the Fed. Just worry about the inequality. Put in some measures, probably taxation related, to redistribute the unequal income. Maybe measures to promote greater bargaining power of the workers, so favor unionization and collective bargaining.

One account of this would be, it will fail. The reason it will fail is it fails to address the underlying problem, which is government creation of a credit bubble. If the government increases supply and reduces price of credit on the truly grand scales of the twenties and the noughties, the resulting credit flood will produce inequality.

The reason is that the inequality is sectoral as well as individual. It is not uniform across the country, across sectors, across regions. What happens is that financial intermediaries and those depending on them profit enormously from a credit bubble. It is this profiting that produces the inequality.

The real divide in public policy terms on this is between those who do not agree that anything much different has happened in government fiscal and monetary policy to explain the bubble, and therefore that you can go ahead and fix it without changing direction, and those who think the fundamental problem is the government credit bubble creation, and that you can and should and must fix this, at which point the inequality will come down.

If you take the last point of view, you’d begin by advocating wholesale impoverishment of the financial sector by withdrawing all subsdidy, enforcing anti trust laws, breaking up concentrations of power, bringing back Glass Steagal…. And reining in the Fed. And closing down the government nationalized mortgage industry.

leroguetradeur said:

Put in some measures, probably taxation related, to redistribute the unequal income. Maybe measures to promote greater bargaining power of the workers, so favor unionization and collective bargaining.

One account of this would be, it will fail. The reason it will fail is it fails to address the underlying problem, which is government creation of a credit bubble. If the government increases supply and reduces price of credit on the truly grand scales of the twenties and the noughties, the resulting credit flood will produce inequality.

leroguetradeur sure likes to get people off on bunny trails. The problems Kumhof documents existed thousands of years before our modern concepts of credit and currency creation were even thought up, back when one said “money” it meant either gold or silver.

Another bunny trail is that articulated by kievite on this thread yesterday: “Computer revolution was an important factor as it permitted pretty sophisticated looting, not possible before of purely technical grounds (HFT is one example).” Again, just like with leroguetradeur’s comment, this is pure, unadulterated hogwash: the rich and unscrupulous were quite good at looting thousands of years before the invention of the microchip.

Certainly one of the key, if not the key, functions of politics is the allocation of material resources. He who has the political power decides who gets what. It’s amazing how much ink gets spilled in an attempt to obscure this simple fact.

I agree with DownSouth. Just because we cannot have perfection (and utopia)does not mean we cannot do much better than our current situation.

Mansoor

Certainly one of the key, if not the key, functions of politics is the allocation of material resources. He who has the political power decides who gets what. It’s amazing how much ink gets spilled in an attempt to obscure this simple fact.

Nobody would seriously argue against the statement that “function of politics is the allocation of material resources”. What you are missing is that changes in technology drive the changes in politics not vise versa.

Computers has probably as profound influence on society as electricity. They make many things prevously impossible, possible and radically changed the society in just 60 years (in we assume that 50th were the first decade computers became avalble outside military.) To assume that political changes occure like “deux ex machina” is naive.

I think that neoliberalism came to the forefront of political stage as a reaction to stagnation coused by New Deal policies. And it was Carter who first started to implement it, not Reagan. In a way, it was an attempt to dismantle or at least set back reforms that led to “state capitalism” and now prevented utilising advances of technology since 30th, and first of all emergence of computers and microchips.

And one reason why neoliberal policies became politically attractive is that private enterprises, empowered by computers and private datacenters (and first of all financial institutions which were at the vanguard of computerization) changed and that change requred redistribution of political power. Computers removed previous restrictions on the size of large companies and make them really global and transnational. Look at the story of Citigroup. And neoliberlism became weapon of choice to counter “national-developmentalism” in the decolonized world, along with the security of wage contracts, pentions, etc in the industrialized countries as empolyees within corporation lost power and top brass gained it. In a way computers eat people…

Just look at the typical Fortune 100 corporation today and compare it with the same, say, in 1960th.

Neoliberalism “was an attempt to dismantle or at least set back reforms that led to ‘state capitalism’ “?

Neoliberalism is “state capitalism,” state capitalism being a system where the owners of capital control the state, where business and finance (read corporations) have a monopoly of political power.

And as to all your sophisms and rationalizations as to why computer technology “required redistribution of political power,” well, you’re protestations are just that, sophisms and rationalizations. Or like I said before: bunny trails, smoke screens. One might possibly make the argument that corporations exploited new technology to gain inordinate political power, but to argue that technological advance “required” this is nothing but 24 kt. casuistry.

I mean really, kievite, no more self-serving argument has been made since Nero insisted that the Christians enjoyed being thrown to the lions because it permitted them to become martyrs.

“Neoliberalism is ‘state capitalism.'”

Exactly right. When one looks beyond all of the political rhetoric of Hayek, Friedman and Mises and focuses on the actual policies they and their neoliberal followers have pursued, it is pretty clear that neoliberalism is neofeudalism. The title of Hayek’s famous book was not really a criticism of socialism but a promise of what you’d get if you adopted neoliberalism.

But neoliberal rhetoric is pretty powerful stuff. All you have to do is ring the “liberty bell” (i.e., just talk about personal liberty and freedom), and a lot of people just switch off their brains.

My favorite canard is the assertion that the government caused the credit bubble. Certainly, the government allowed the credit bubble to happen, and the GSEs were turned into mortgage fraud laundries that facilitated the buble, but this happened because government is controlled by Wall Street, not the other way around.

Blaming the government for the credit bubble is like blaming the dummy for what the ventriloquist said.

Neoliberalism is “state capitalism,” state capitalism being a system where the owners of capital control the state, where business and finance (read corporations) have a monopoly of political power.

I think you mix-up different aspects here. First of all owners of capital control the state at any form of capitalism That’s an immanent feature.

I would accept that both are forms of state capitalism but you need to accept that they are two different flavours of state capitalism. One important difference is that in first brand of state capitalism unions were at the table, while at the second they were on the table.

Also important is the fact that growth of political power of financial capital (on which we both agree) at some point turns quantity into quality.

As far as for prominence of financial sector this is a common phenomenon for aging empires. Here you fall short in plausible explanation of why this has happened. Your theological explanation that essentially “evildoers” somehow grabbed the power smells George W. Bush mentality.

I would also like to refer you to your favorite Kevin Phillips for more detailed explanation of the dynamics of this transformation.

Kievite said: “First of all owners of capital control the state at any form of capitalism That’s an immanent feature.”

Have we now stooped to just making stuff up? Apparently so. “Control of the state” is certainly not a “feature” of capitalism. In fact, just the opposite is true:

The early champions of the free market, most of them British, had in fact looked to industry mainly to create the wealth of nations, as the title of Adam Smith’s classic book had it, not the power (emphasis Schell’s) of nations, which had been the preoccupation of their mercantilist predecessors. The advocates of laissez-faire declared the independence of economics from state power. (The eventual coining of the word “economics,” identifying a distinct realm of human activity subject to its laws, was one sign of their faith in that independence.) The market worked best, the worldly philosophers of the late eighteenth century believed, when the government kept its hands off it.

–Jonathan Schell, The Unconquerable World

And you say “growth of political power of financial capital…at some point turns quantity into quality”? Quality for whom? Certainly you can’t expect us to believe that an all-powerful financial sector results in quality for anybody but the financial sector.

And my “theological explanation” of how corporations have grabbed power? Please, kievite, now you’re beginning to sound like the New Atheists. They present their dubious interpretations and analysis as self-evident, indisputable truths. They operate not through the usual means of civil discourse and persuasion, but via intimidation and intellectual decree. Upon any mention of the words “ethics” or “morality,” they trundle out their trusty old weapon, which is to brand their enemy as a religious fanatic. Having thus painted their opponent with the face of evil, they can dismiss his arguments without ever having to debate their merits.

kievite,

I know it’s late in the thread, but I wanted to come back and comment on the following statements of yours, because I believe it is extremely important that they be rebutted:

• As far as for prominence of financial sector this is a common phenomenon for aging empires. Here you fall short in plausible explanation of why this has happened. Your theological explanation that essentially “evildoers” somehow grabbed the power smells George W. Bush mentality.

I would also like to refer you to your favorite Kevin Phillips for more detailed explanation of the dynamics of this transformation.

And, from a comment of yours lower in this thread:

• I think that conversion of the economy to casino capitalism was the result of attempts to adapt to new geopolitical situation of 80th (and first of all rising price of oil, see Carter doctrine ) and the decline of the US empire (see Kevin Phillips).

You are essentially making two arguments here.

1) You are asserting the decline of the American Empire is attributable to a failure to adapt to changes in the geopolitical situation, and had nothing to do with a moral decline in America, and

2) That the decline of empires, and by extension the American Empire, is inevitable.

Furthermore, in order to give yourself an aura of intellectual legitimacy, you enlist Kevin Phillips on your team.

As to argument 1), Phillips does indeed place what’s happening in America within a geopolitical context. However, he makes very clear that he believes the failure to respond appropriately to this changing geopolitical environment is due to moral turpitude. Bad Money is replete with normative assessments. Phillips explains himself and sets the tone in the introduction:

Money is “bad,” in the historical sense, when a leading world economic power passing its zenith—-before the United States, think Hapsburg Spain, the maritime Dutch Republic (when New York was New Amsterdam), and imperial Britain just before World War I—-lets itself luxuriate in finance at the expense of harvesting, manufacturing, or transporting things. Doing so has marked each nation’s global decline. To institute the dominance of minimally regulated finance at this stage of U.S. history is a bad idea. (Emphasis Phillps’)

“Bad” in the systemic sense further applies to letting a financial elite elevate, expand, and entrench itself as a country’s GNP- and profits-dominating sector, as has been done in the United States over the last quarter century.

Phillips goes on to spend about 80% of the book, which you blithely elect to ignore, to expand on this theme, elucidating the moral rot that sits like a wolf on America’s doorstep.

Now as to argument 2), there certainly is a lot of black in Phillips’ picture. But he is not nearly as fatalistic as you are. Here’s Phillips from Bad Money again:

No previous leading world economic power has enjoyed a full-fledged manufacturing renaissance after becoming unduly enamored of finance. However, should the United States decide to imitate the commitments of high-value-added manufactures and exporters like Germany, Japan, and Switzerland, some success would be likely…

[….]

Instead of listing any more leaden linings, let me close with a silver lining. The thirty- to forty-year tumble from national preeminence that made life more glum for most folk in seventeenth-century Spain, eighteenth-century Holland, and the Britain from 1910s to the 19502 may be somewhat moderated for the United States because of its position as a North American continental economic power with a large resource and population base rather than a weaker European maritime periphery. And further abandoning the hubris of military and financial imperialism would also help because both postures represent drags on the American future.

So why are you so insistent in painting all in black?

I believe it is because you are an apostle of what Nietzsche called “passive nihilism,” or the credo embraced by “the children of darkness,” as Reinhold Niebuhr put it. The function of these arguments, Stephen Toulmin observes in Cosmopolis, “is to show members of the lower orders that their dreams of democracy are against nature; or conversely to reassure the upper class that they are superior citizens by nature. (emphasis Toulmin’s) The entire rhetorical strategy is designed to elicit a sense of surrender and defeat and induce torpor on the part of the lower orders.

But such fatalism and defeatism is a distortion of the historical record. As David Sloan Wilson counters this attitude of capitulation in Darwin’s Cathedral: “Confront a human group with a novel problem, even one that never existed in the so-called ancestral environment, and its members may well come up with a workable solution.” As Wilson goes on to explain, the religious, scientific and historical determinists who paint solely in black promote the algorithm that “everything that has taken place since the advent of agriculture counts for nothing.”

It’s amazing that when Nietzsche’s “superman” or “Dionysus” finally arrived on the scene in the 20th century, he wasn’t the ridiculous cartoon exemplified by this sculpture from Arno Breker, Hitler’s favorite sculptor, or some equally nonsensical character from an Ayn Rand novel, but a swarthy little man who hailed from India’s petty bourgeoisie. Mahatma Gandhi took a little pinch of the nonviolence inherent in Tolstoy’s Christian pacifism, a large tablespoon of the willingness of Russian revolutionaries to self-sacrifice for a cause, a dash of the action figure attitude embraced by the British soldiers he met and admired, a cup of the sense of civic duty, honor and sacrifice that he believed typified the British character, and three cups of a profound personal spiritual and religious faith, and from these unlikely ingredients synthesized a moral, political and religious doctrine that was totally new, that no one thought would work, but that completely inspired and revolutionized the world.

Here’s an anecdote told by Jonathan Schell in The Unconquerable Worlda that captures the sort of man it took to achieve this:

Everyone forms opinions and beliefs, but most act on them only up to a certain point, beyond which fears, desires, doubts, prudence, laziness, and distractions of all kinds take over. Gandhi, as it turned out in South Africa, belonged to the small class of people, many of them religious or political zealots, who are able to act according to their beliefs almost without condition or reservation… On a train from Durban to Pretoria, a white man had him thrown out of the first-class compartment for which he had paid, and when he protested the conductor dumped him onto the station platform. “I should try if possible,” as he later wrote, “to root out the disease [of color prejudice in South Africa] and suffer hardships in the process.” It was a decision, as things turned out, that would guide his actions for the next twenty-one years.

I need someone to explain to a non-economist how the governemnt created the crdit bubble.

I understand about the low Fed rates increasing lending thing(to some extent).

But I would think the question is whether those low rates caused the credit bubble. I have seen nothing that leads me to think the credit bubble would not have happened if the Fed rate was three, or four times higher.

The margin for profits by investment banks were so high that any increase in the Fed rate would have not even have given the banks a second thought.

The government didn’t cause the credit bubble. Neither did the Fed (which is a private bank, not the government).

Could the government and the Fed have prevented the credit bubble? Sure. But failing to stop something is not the same thing as causing it.

The funny thing is that almost everybody who accuses the government of causing the credit bubble are dead-set against any type of government regulation of the credit markets and money supply.

In any event, those who believe that the Fed’s tinkering with the interest rates has any real effect in reining in financial speculation don’t have history or the facts on their side. The quantity theory of money is complete bunk, and Paul Volker proved that in the 1980s as borrowing didn’t really slow down even in the face of a fed funds rate of 20%. Yes, he “stopped” inflation, but only by killing American manufacturing, which had nothing to do with the inflation in the first place. The stagflation of the 1970s, just as the stagflation of today, was caused by leveraged financial speculation in consumer staple commodities, not rising labor wages.

If you want to stop debt-financed financial speculation, criminalize it.

Actually Tao, you just proved yourself wrong. The government did (at least partly) cause the credit bubble by ‘decriminalizing’ it. They did that by repealing Glass/Steagal.

I’ve always wanted more evidence about the financial, political and social climate that led to the repeal of Glass Steagal-PBS seems to have done a fair job at outlining some of the issues-

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/wallstreet/weill/demise.html

Right now I am just formulating some ideas on this after rediscovering Theodore Lowi’s book ‘The End of Liberalism: the Second Republic of the United States’ wherein the history and politics of regulatory law making is reviewed.

I’d like to discuss this here because the talk on this blog seems to center around a missed factor in how the regulatory agencies created by Congress in the past 75 years been set up to fail by the very authors who wrote them-they failed to make the rules unambiguous, they failed too often to do their homework, but most importantly, they were afraid of creating and facing controversy. The final sin was a large scale unconstitutional shift of power by placing the actual burden of actually fleshing out the law on the executive branch. Most regulatory ambiguities have centered around this very problem in that the executive branch, inside of administrative courtrooms, gathers the information Congress should have and passes decisions which then create a body of law. Granted, Glass Steagal seems to have been one of the less ambiguous body of law inside an otherwise soggy swamp of regulatory hell but apparently, at least according to the outline given at Frontline, there was still a lot of wiggle room.

In short, while I’m still looking into this complex topic, I would merely point out the bad regulatory law is not necessarily better than no regulatory law. In law, like the proverbial path to perdition, good intentions flower the path with as many points as front lawn dandelions of May. Is the reason Glass Steagal looks so good merely because so much bad law has come out of the regulatory efforts Congress has made since 1934?

Now, I am already hearing the stones landing on my patio floor and one may sail through the glass soon so I’ll need to close the shutters.

There, now that I’m safe for a minute let me just state that I am all in favor of good regulatory law when there is a real perceived need for it and we seem to be one of the neediest societies around and yet we lack a really sound regulatory atmosphere in our political culture. Business activities need to be hedged in by law; laws need to be hedged in by experience and freighted with the meaning of discovery that history brings to the well educated legislator. A good example of this is the Civil Rights legislation-which is about all we have in the way of really good law from the time frame from Reconstruction till today.

So my first point is: while a good body of regulatory law is needed, we as whole suffer a deficit on this account.

Second, and this is more of a hypothetical but looking at the timeline given by Frontline, the actual repeal of Glass Steagal was just an overt admission of what had actually been done covertly.

More on this later, have to reopen the shutters.

The government didnt cause it, but it enabled it.

Under Roubin commercial banks that were genuinely too big too fail were permitted to become investment banks while any talk of derivative regulation was shut down by Roubin and Summers.

The government’s inability to cure its chronic trade deficits also fed into the bubble, as Chinese purchases of treasuries to recycle their surplus and keep the yuan down exacerbated the already too low interest policies of Alan Greenspan.

Finally, the Republican push to create a “home ownership” society to cement a permanent conservative majority pushed too many into pursuing subprime mortgages that were then rebranded as AAA assets [and the demand for high yield AAA like sub-prime CDO’s came about directly from the low interest policies of the Fed/Chinese government.]

Nope. This paper shows quite clearly that the inequality is the root problem, and if it is addressed, the credit bubble will solve itself. Think about it carefully.

Was there a point to all that? How can charting government debt can be related to a percentage of personal gain?

The US has averted 3 or 4 self-inflicted monetary meltdowns. I doubt it can be avoided this time around. There really is no accounting for greed.

According to Martin Armstrong, the world is cycling, as always, when the monetary baton is passed to the next strongest economy in line. Happens on a constant basis throughout history when dealing in fiats, we just happen to be living it.

Please re-read the chart series. They start with HOUSEHOLD debt to GDP.

I have a different nit to pick with household debt to income charts, at least the long term ones.

Assuming the largest debt is a home mortgage, mortgage rates in the early 80s were 12%. They are now below 5%. Any meaningful picture of the consumer’s financial state at any point in time should use debt service cost, not debt level.

Then low cost home equity loans and cash out refis came into vogue some time in the latter 80s. So the balance of consumer debt is not carried at credit cards rates or even auto loan rates. At least not as much.

So debt service cost charts would look very different.

But projecting into the future under a rising interest cost scenario would look very bad, however. We’ll probably get to use Spain as test lab soon in case we’re not sure what happens.

In the 1980s most people paid cash for their cars.The use of leases and loans was really not common at all. It was both supply and demand side. Automakers were not into using financing to push cars and as another profit center, and there was still stigma on the borrower end.

Ditto credit cards. In the later 1980s banks were just beginning to offer no-fee cards, which changed their incentives as to how to take profits. Before they made money on every type of customer, the sporadic user, the pay off in full every month type, and the ones who carried balances.

The shift was also facilitate by the 1986 tax reforms. Ironically, before then, all consumer interest payments were tax deductible, yet few consumers borrowed because banks were chary with credit and it was considered a bad idea, consumers understood that the cost of buying would be higher if you bought stuff on credit.

As to super high mortgage interest rates in 1980, at least in NYC, consumers were not taking out fixed rate mortgages. Adjustable rate mortgages with floors and ceilings were a much more popular product.

In CA we had a housing bubble from 76 to 80. I arrived from Chicago after the party ended, but discovered that they invented “creative financing” in CA. The best deal was to assume the old loan at a favorable rate, but the seller usually bumped the house price if he had a 30 year fixed assumable loan at ,say, 8%. The next most popular loan was a 5 year balloon, but those still went for 10%.

We seemed to have lots of yuppies borrowing and leasing cars too. The ones that were trading down to cash cars were told to do so by their loan broker so they could qualify for a home loan on a CA property which was selling at 2.5X the national median.

As the 80s progressed, the smart more was to do a cash out refi at a lower interest rate and pay off all other loans or buy the new car. Then you would still write off the entire new mortgage.

But the point I was trying to make above is that interest expense has fallen dramatically over the last 30 years, so just looking at household debt to income data gives a skewed picture of personal financial stress.

Then today when I see the large number of 35K-60K SUVs on the road, I can’t help thinking maybe we also have a large number of consumers that just bring the problem on them selves.

But having been thru 2 housing bubbles already, I’m an expert on stampedes and I don’t think the government should be allowed to orchestrate that game with their financial buddies.

(Days later) Most all the comments, get it. Versus how the IMF think tank feels about things.

Again, Martin Armstrong doesn’t dwell in the past, notes it, charts it, puts it in his own cycle form then carries it out to 2012, past 2016, then into future decades disregarding the “we are all doomed” scenarios. Markets live on just the sandbox won’t be in our backyard anymore. Like I always say, great time to start another banking system, this one is broke and propping it up is not helping matters.

Consumers can save all they want but it will be government debt that breaks their backs.

Let’s start at the basics. Growth is stable in any given cycle if all the goods produced are also consumed. This can happen when the prices are set in such a way that the consumers together earn enough to buy all these products. (Let’s ignore for the moment that people, both on the investment and consumption side might have savings. As such, let’s assume that the total amount of money floating around is roughly equal to the value of the produced goods/services) If all the products are sold, the investors who own the means and rent the labor will have made a profit which they’ll want to reinvest in order to also make a profit on that sum.

Now, there are 2 things that can disturb this situation: worker savings can only happen insofar as they don’t cause ‘underconsumption’, and worker wages have to be high enough to buy all the goods, putting limits on the amount of income inequality that can exist. This latter point is fairly important, because your model seems to assume that ‘investors’ (who, by def, will save a large %age of their income) will consume roughly as much as a group of people will. To be brief: this is, of course, nonsense, or they wouldn’t be so good at saving. As such, saving causes slight imbalances, which are generally interpreted by the corporation owners as an inducement to fire ordinary workers (or to replace them by improving production efficiency). Additionally, investors also have an increased tendency to want to get high returns on all the money they’re saving, and they will want to reinvest this money into either production expansion or efficiency gains. Yet both of these investments require consumption to increase in the next cycle, and there will be less and less room for this once you start reducing the (aggregate) wages earned by the part of the population that has the least money available discretionarily. This, then, will also cause the employers to fire workers — because they will not be particularly inclined to reduce their own pay — even though this causes further imbalance down the road, esp. once this starts happening on a national (or even int’l) level. (I would suggest that ‘financial investment’ only happens once legit investment opportunities start to run out because they’re all already taken: all that comes from this is asset bubbles)

Now, one way to cover up the problem created by these imbalances is to lower interest rates and remove borrowing restrictions. Yet this only gets you so far. Another is to blow a housing bubble, because this affects more potential consumers. Both have happened, yet both are untenable in the medium-long term.

To get to your question: debt reduction is indeed only going to be possible once you decrease the inequality, because what it means is decreased consumption, and this means increased layoffs. Yet this will have to be done on a national level, as money flows in and out of economies create additional problems for stability. (Though some of this is interpreted as good in the short run)

Anyway, if you think you might want to read more in this vein because it might help you get a better understanding of the mechanisms that would underlie any model you create, see this review (at the IMF website).

Well if the facts aren’t on your side, then just baffle ‘em with bullshit.

Amazing how you went through all that convoluted exercise in verbosity just to avoid the only two things that must happen, regardless of how we get there, in order to avoid a deflationary spiral: 1) The debt load of 95% of worker households must be reduced and 2) the consumption of those households must be either maintained or increased.

#1 can be achieved either through debt default, debt jubilee or repayment. Repayment requires higher salaries for workers.

#2 can be achieved through higher pay for workers, or from taxing the rentiers and redistributing the proceeds to the workers.

There are no other ways out. What makes the necessary adjustments unacceptable to the rentiers is that it encroaches upon their notion of economic superiority, and this notion is not without validity. Numerous studies have shown that sentiments of economic superiority are relative, not absolute. It’s only necessary to be richer than those around you to feel rich. So one way to enhance one’s sense of economic superiority is to impoverish everybody else. This goal seems to be the lifeblood of neoliberalism.

And by the way, there is no greater mandarin of neoliberalism than the IMF. I take everything it says with a generous dose of salt.

The debt load of 95% of worker households must be reduced and 2) the consumption of those households must be either maintained or increased.

#1 can be achieved either through debt default, debt jubilee or repayment. Repayment requires higher salaries for workers.

#2 can be achieved through higher pay for workers, or from taxing the rentiers and redistributing the proceeds to the workers.

That’s not very plausible. The political power of workers as a countervailing power continues to diminish. And the base is very low anyway as with dismantling of the USSR unionized workers suffered almost complete political annihilation. At the same time, the standard of living is still way too high for the Egypt style uprising of serfs.

One interesting side effect of this crisis is that top brass realised that layoffs did not negatively affected (and sometimes substantially increased) productivity and that they still can be continued without hurting profits as more and more tasks is being automated and/or outsourced. In some cases corporation needs little more then top brass and robots.

The general trend is squeezing wages, downsizing workforce and conversion of permanent workforce into temporary. Retirement of baby boomers provides ample opportunities for that.

Gosh, kievite. Nietzsche saw through that little bit of sophistry when he was only 18 yers old. If man were to buy into your “fatilistic principle,” the young Nietzsche wrote in an early essay, it “would make him into an automaton.”

It is the “categorical imperitive”(Kant)of the middle and lower class citizens to turn the tables on the goverment/bank oligarchy by using their right to default. This is the only solution in the long run.

The reason “financial investment” happened is because it was more profitable than “legit investment.” Why was it more profitable? Because when financial investments went bad, the federal government would step in and indemnify the banks for the losses resulting from their high-risk lending activities. In his book Bad Money Kevin Phillips cites 12 separate instances between 1982 and 2007 where the federal government intervened and did this.

Again you provide a theological explanation that misses other factors like a price of oil, restored compertitivness of Japan, Germany and some other countires from the picture. I am more inclined to think that that financiazation of the economy was a rational rection directed on overcoming the stagnation in other scheres and first of all manifacturing and in way it was successful in posponing the day of reconing for another 20 years.

So our differences can be summarised as following:

I think that conversion of the economy to casino capitalism was the result of attempts to adapt to new geopolitical situation of 80th (and first of all rising price of oil, see Carter doctrine ) and the decline of the US empire (see Kevin Phillips).

You think that it is result of “evildoers” actions based of excessive greed (aka higher profitability) or similar individual/group motivations.

I tend to thing that this is too simplistic/theological explanations.

Your explanation doesn’t fit, while DownSouth’s explanation does fit.

A rational response to the rising price of oil was to invest in renewables; stifled under Reagan by increased fossil fuel subsidies and a temporary drop in the oil price. The decline of the US empire did not cause the change in manufacturing (the changes in tariff policy did, the choking grasp of big business on the US economy to the suppression of small business did, the loosening of capital controls to allow big business to move its money abroad did, the “free trade” agreements allowing outsourcing did, etc.) Arguably the decline in US manufacturing caused the decline of the US empire, of course.

DownSouth’s explanation, on the other hand, makes perfect sense and matches the evidence. Repeated bailouts of even *criminals* in the finanical industry made it an attractive place to “invest” money with “no downside”.

kievite,

You’ve trundled out that trusty old New Atheist weapon again. Pray tell, just what do excessive household debt and declining worker pay that result in a deflationary spiral have to do with theology?

I am confused. Did I say otherwise? My point is merely that the author does not seem to grasp the mechanisms that underlie his model, and that, as such, he seems to confuse cause & effect quite a bit.

Additionally, I am quite aware of what the IMF is and does, but I think it would’ve helped if, before commenting, you’d had a look at the link, as it points to a review (by guy at IMF research) of David Harvey’s The Enigma of Capital, mentioned in the post below mine as well.

Anyway, to the extent that my post was unclear, I apologize. To briefly summarize my criticism: 1. there is no way to deleverage without causing further harm (because it further depresses consumption, which causes layoffs because it increases the s/d imbalance). 2. The idea that investors consume in any meaningful sense is nonsense, yet what is less acknowledged is the fact that savings lead to an increased amount of cash looking for investment opportunities, which leads to investors investing in risky stuff (asset bubbles) or job layoffs/worker pay decreases (because this increases the amount of money the production owners get in the short run, even while it increases the future mismatch between production/consumption). Yet none of this can easily be understood or modeled in the model offered by the post author.

As DownSouth says, deleveraging can happen with a debt jubilee or mass bankruptcy or increased worker wages without reducing consumption, but not otherwise.

Marxists can explain rising income inequality too: TRPF. Amazing, this also explains (a) financialisation, (b) Minsky’s Ponzi investors, (c) the hollowing out the the US economy, (d) the rise of debt. Just about everything follows from TRPF. Furthermore, the evidence is there for it too, as noted in this book review:

The best early explanation of TRPF is given by Grossman here: http://www.marxists.org/archive/grossman/1929/breakdown/

What Kumhof demonstrates with his models is a phenomenon that’s been known and described for a long time. It’s called the Matthew Effect, which was expressed in the New Testament as follows:

For unto every one that hath shall be given, and he shall have abundance: but from him that hath not shall be taken away even that which he hath.–Matthew 25:29

and

For whosoever hath, to him shall be given, and he shall have more abundance: but whosoever hath not, from him shall be taken away even that he hath.–Matthew 13:12

Gross inequality and the accumulation of great worldly wealth were not morally acceptable to the early Christian Church. (The ethics of the early Christian Church, which began as a revolutionary Jewish mass movement of radical liberation to oppose Orthodox Judaism, should not be confused with either the medieval Christian Church or the Christian Church of today, which themselves became bastions of orthodoxy.) So in order to ameliorate the consequences of the Matthew Effect, the early Christians fell back on Old Testament solutions like debt forgiveness and jubilee and prohibitions against charging interest. There were the old prohibitions, such as this one:

If you lend money to any of my people with you who is poor, you shall not be like a moneylender to him, and you shall not exact interest from him.–Exodus 22:25

And new invocations, like these:

And if you lend to those from whom you expect to receive, what credit is that to you? Even sinners lend to sinners, to get back the same amount. But love your enemies, and do good, and lend, expecting nothing in return, and your reward will be great, and you will be sons of the Most High…–Luke 6:34-35

and

Do not lay up for yourselves treasures on earth, where moth and rust destroy and where thieves break in and steal…–Matthew 6:19

Of course the morality of early Christianity (and early Judaism too, before it became Orthodox) is anathema to capitalism. So it became necessary to murder God, the success of this enterprise being summed up in Nietzsche’s famous assertion in Zarathustra: “God is dead.”

But the basis of early Christian and Jewish morality was not just theological. There was a practical, secular basis for the morality as well. This was recognized by American revolutionary thinkers, such as Thomas Jefferson, when he wrote:

Some have made the love of God the foundation of morality… [But] if we did a good act merely from the love of God and a belief that it is pleasing to him, whence arises the morality of the Atheists[s]… Their virtue must have some other foundation.

The importance of Kumhof’s work is that it is not only an empirical confirmation of the Matthew Effect, but it takes the next step, which is to show (in a very secular way) that gross inequality and the accumulation of massive individual fortunes has secular consequences: it leads to financial crises and the destabilization of society.

Nominalism, the Reformation and the Enlightenment, just like Judaism and Christianity, began as revolutionary mass movements of radical liberation. But, just like Judaism and Christianity, with time they got turned on their heads and became orthodox—-tools of the status quo. The New Atheists (Ayn Rand and Richard Dawkins being the leading apostles) are perfect examples of how atheism, or secularism, has been corrupted so as to become the handmaiden of the rich. Neoclassical economics, with its Vatican located at the Chicago School of Economics, is another.

According to Michael Allen Gillespie: “Nihilism for [Nietzsche] is the result of the fact that the highest values devalue themselves, that God and reason and all of the supposed eternal truths become unbelievable.” This is without a doubt true. But it begs the question: Why do the highest values and eternal truths become unbelievable? Is it not accurate to say that a belief in the highest values and eternal truths does not serve the interests of some, and that we are constantly bombarded with propaganda—-both religious and secular—-to destroy our belief in the highest values and eternal truths?

I am most happy to report that secular revolutionaries like Kumhof, Herbert Gintis, Samuel Bowles, Ernst Fehr and others working in the discipline of economics are not alone. They are joined by revolutionaries from other disciplines. These include David Sloan Wilson (biology and anthropology), Peter Turchin (ecology, biology and history), Jonathan Haidt (psychology), Robert Boyd (anthropology), Stephen Toulmin (philosophy) and many others.

What I am not happy to report is that there doesn’t seem to be a concomitant religious revolution taking place. Where have the radical religious liberationists, people like Reinhold Niebuhr and Martin Luther King, disappeared to?

The age old question, how to defeat a loose knit pack of sociopaths, which seemingly rise organically with-in all man made systems…with out becoming one your self or treating others as they would.

Skippy…the I want[s / need vs. the why would methinks before my self. Too turn unencumbered giving into self hate is their greatest desire, it is the light they can not bare, so give often and freely…it is their anathema.

All false gods (like money) always destroy themselves. Because they cannot keep up with what they themselves have created. Extreme love of money will also be destroyed by none other than people themselves. I just pray and hope that the process is not too painful.

Mansoor

DownSouth,

The judeo-christian religious groups that have been at the forefront of supporting a more egalitarian worldview have probably been the liberation theologists (Paulo Freire, Myles Horton, Paul Farmer) and I suspect Quakers. They have been quite busy in Latin America and Africa. It is hard to cry over the suffering endured by the declining American middle, with their leverage issues, when you compare it to what goes on in developing countries. While our cheap consumption is certainly connected to their suffering, most of those groups have focused on the developing countries. When you hear about priests being killed in Latin America, they are generally supporters of liberation theology. It is quite funny that the Evangelicals, through prosperity gospel, were part of the equation pushing religious people in the American middle into high rates of consumption and leverage. It is really quite frightening how that prosperity movement has distorted Christianity into a consumption and not morally embedded endeavor. Nonetheless, judeo-christian groups still have a large part to play in development programs, both in positive and negative aspects. The evangelical effect can be seen in attempts at the criminalization of homosexuality in African countries and push towards teaching abstinence over protection.

Downsouth,

“But the basis of early Christian and Jewish morality was not just theological. There was a practical, secular basis for the morality as well. This was recognized by American revolutionary thinkers, such as Thomas Jefferson, when he wrote:

Some have made the love of God the foundation of morality… [But] if we did a good act merely from the love of God and a belief that it is pleasing to him, whence arises the morality of the Atheists[s]… Their virtue must have some other foundation.”

There is a huge problem with theological interpretation of morality: it is absolutist, which is to say that it refuses to recognize the importance of context and consequences when evaluating the morality of certain choices.

But morality does not exists in vacuum. It is a tool for the survival of a particular social organism(for example, state), no more no less. And if the preservation of society justifies the action of the organs of the state, then it is logical to see such actions of the state as moral or at least “a necessary evil” and the question of morality of inflicting harm or even death on individual(s) within the state or other states by a state power “for greater good” became much more complex. To avoid this dilemma orthodox Christianity identifies itself with state. Here an interesting notion of moral hypocrisy of Catholicism arise…

Obedience to suprime religious authority and dependence on ancient texts are also a poor starting point for dealing with complicated modern moral issues such as genetic engineering and stem cell research.

kievite,

But the very thrust of my argument is that morality isn’t religious based.

And again, this conflation of religion and morality comes right out of the New Atheists’, and religious fundamentalists’, playbook.

Downsouth,

Many of our elite know that morality is important. That is why Warren Buffet and Bill Gates have set the example. These people know that the only way our current economic system model will work if the rich become more “humanity serving” or at least “fellow citizens” serving.

We need to follow the example of Germany or Japan. These societies highly value social stability and the idea of a “minimum standard of living” for all members of their society.

If our elite don’t make this change they will simply take our civilization over a cliff.

Mansoor

Your error is in the use of the word “many”. A few of our elite understand the problem. Unfortunately, their warnings are not being heeded, while the most unelightened of the elite continue to run the country to their personal short-term advantage.

I have to agree with your interpretation of the cited scriptures and your notion of the early Christian culture.

I would add that the Master advised the wealthy to give their worldly goods to the poor and dedicate their lives to following him on a spiritual journey. In addition, the Old Testament gives accounts of the punishment of the nation of Israel for grinding the face of the poor into the earth and having such callous hearts.

Furthermore, the Master clearly spelled out the choice to be made regarding the pursuit of wealth and power in the temptations of Christ. Socrates warned his fellow Athenians of the dangers of greed, as well.

People consumed with the accumulation of vast wealth are not to be envied, but rather pitied. They’ve willing placed a millstone around their neck. The problem is they are going to take everyone else down with them when they slip off the boat. Greed is not good, greed is bad, plain as day.

@avgJohn: Hey man, if you want to work with me on starting a political-gathering-of-democratic-force clearinghouse/ website started with me, as we talked of earlier, email me @ strockenz@yahoo.com. Lets get something going. I have a few others that are interested. It’s really hard to get the snowball rolling. I wish there were a mechanism for people on these sites to contact one another. I feel like I’m spamming the thread and I don’t want to do that. If we can’t get together but in these forums we remain practically impotent. The forum is just a steam release.

Interesting analytical construct.

The last 30-40 years in the US have produced an economy where most have needed to substitute debt for income because the cost of living (food shelter and energy, clothing, and health care) has increased far above the household’s ability to earn. Debt consumption has been encouraged because it is a palliative to the masses and an enormous profit machine for those who sell and market debt. Simply put, the Cost of Living = income + debt (P+I) = over leveraged consumer = huge profits for debt merchants = economic collapse.

The remedy for this economic disaster is to re-balance the cost of living with the household’s ability to earn. A fundamental factor in achieving this goal is the restructuring of all consumer debt by reducing the principle and/or discharge of the debt. Next the economy must create jobs with income levels sufficient to support the cost of living for the masses (by increasing taxes on goods and services produced outside of the US and decreasing taxes for the same produced inside the US while eliminating a company’s ability to booked profits from sales in the US overseas or moving offshore to avoid US taxes, and apply RICO to white collar crime). Further, the cost of living must fall (cost reduction must occur in housing and energy, health care and finance).

Looking backward to FDR and his policies for resolving a similar crisis based on debt and income inequity should be where we begin. Current economic problems can be resolved if we choose to resolve them.

The boom / bust cycle of the last 30 years with the creation of bubbles and tax policies that transfer the wealth of the consumers to the top 10% income earners is doomed to fail. Why the current Administration, Congress and the FED are continuing these policies is a mystery. Unless it is born of ignorance or a deliberate plan to support their base (the top 10%).

I agree that we must make major changes to the economy. I would like to bring up the question of what is ‘cost of living’? I assume we would mean survival cost at the minimum and the ambiguous American Dream on the other end. But what are we shooting for?

This is important to think about because the cost of living today is (in my opinion) more than what it was say in the 1950’s or 1970’s. I think it is best explained using examples:

1. How many computers did our grandparents have when they were working? (parents)

2. How many cars?

3. How many TV’s? DVD players? DVD’s?

4. How much did they pay for cable? Internet?

5. How much was a house as percentage of income in 1950 or 1970?

6. How many xBox/PS3/Wii did they have?

7. How many cellphones and how much did they pay per minute?

The answer to most of these questions is none. Food and other necessities cost more but housing cost less. And with less consumption my grandparents generation saved more and helped create wealth in the country.

One problem we face as a nation is the we have upped the acceptable cost of living in the nation during a period in which we have experienced wage stagnation. I’m 28 and will have difficulties earning a wage with the same purchasing power my parents and grandparents had. I also live during a time period where having the internet is a necessity as well as a functional computer. Most people can’t imagine a life without a cellphone.

Most of the other ‘necessities’ are not important and probably come back to discussions that are generally had about the consumption rate of my parents and my generation versus that of our Grandparents.

Much of this consumption has been made possible because these items are manufactured in poor countries and are thus able to be sold for less than if they were made here. Implementing the suggestions you make of decreasing imports through tariffs, increasing domestic production to produce jobs and also increase wages for those new jobs to a ‘living wage’ (I know you didn’t use the term, but it seemed to be the type of level you mention) will increase the cost of living and lower the standard of living for people in the country.

That to me is the biggest problem we face going forward. My generation is going to have to give up things we grew up expecting because our parents structured society so they could purchase them with credit at lower production cost prices. Will we accept that responsibility in order to pass on a better country to our kids? I doubt it because our parents did provide a very good model to follow.

James,

Does a $200 pair of Nike shoes cost you less because it cost Nike $5 to make them using what is essentially slave labor? How about an $80 Ralph Lauren shirt?

And when the people of Mexico pay exorbitant rates for telephone services or banking services, far higher than what you pay in the U.S., do you share in that rip off?

What about all the military spending, both directly on U.S. military operations as well as military aid to the militaries of U.S. client states, that is necessary to enforce these arrangements?

Your mental picture may not necessarily be false, but it is incomplete.

There is cost inflation on brand names in every category of product from every country of production. An Omega watch cost $500 dollars in China but over $2000 in the US, both are manufactured in Switzerland. Wine can cost $1,000 of dollars per bottle but not cost any more to produce than a $10 dollar bottle. That has little to do with my points.

How many plasma TV’s are manufactured in the USA? is there a $50 dollar to $2000 dollar mark up on those? None are produced in the USA, and no there isn’t that kind of mark up. Electronic goods might operate at a good profit margin but not at the same level enjoyed by name brand mark up in clothing and other luxury goods. Shifting manufacturing to the USA will not effect all products but it will affect enough products to matter.

That being said, I am very much in favor in increasing American manufacturing. I

On defense spending, during the entire decade of the 1950’s defense spending never dropped below 10% of GDP. 60’s 7.4. 70’s 4.6. While fighting two wars our defense spending never topped 4.7% during the last decade and it spent most of the last decade around 3%. If that is the cost of maintaining market access then it is very affordable, a lot less expensive than the money we spent propping up, rebuilding, and defending W. Europe from communism in the 40’s, 50’s, 60’s, 70’s, and 80’s.

Now I’m not advocating exploitive overseas manufacturing practices because I strongly support redeveloping the USA’s manufacturing sector. I’m just stating that the cost involved in maintaining is economically worth the cost if you don’t factor in the job losses and competitive advantages lost.

Without even getting into the moral aspects of having to use military force (you know we’re talking violence here, don’t you?) to maintain market access, do you really think it’s fair for me to have to shell out so that Bank of America can screw over Mexicans?

DownSouth,

No, I do not think it is fair for the US military to be used for US corporations to screw over anyone. I think the recent housing crisis and it’s aftermath has shown us that the gov’t doesn’t even protect our banks from exploiting USA citizens and a lot of work needs to be done to stop them.

I do; however, believe that the strong military force of the USA helps insure USA and usually European/Japanese/Canadian/Australian/New Zealand access to necessary natural resources and markets. Our navy helps to maintain free and open trade lanes. Our military budget alone helps keep down the military spending of our allies because they can rely on the USA for their national defense and; therefore, can spend less on the military and more on social programs.

How much has the USA (and the world) benefitted from free, open, democratic, and capitalist countries in S. Korea, Germany, France, Turkey, and Japan to name a few? US military force and resources were used to keep those countries from becoming communist.

I want to be clear that I do not mean they military should be used little.

James:

Take the 57 minutes and listen to Dr. Elizabeth Warren and her study: “The Coming Collapse of the Middle Class.” I believe this will answer yor questions and also change some of your thoughts on the COA and consumption. Briefly some detail:

Spending Less

We actually spend less on an inflation-adjusted basis on many things nowadays:

•32% less on clothing

•18% less on food – including groceries, eating out, and yes, even Starbucks

•52% less on appliances

•24% less on car expenses, per car (although the need for two cars in suburbia is more costly)

Spending More

Not so fast, we also spend more in many areas:

•76% increase in home mortgage payments . Surprising, the actual house size didn’t grow that much based on number of rooms (5.8 vs. 6.1). I wonder if this would hold true if it was based on square footage, however, as my research on that indicates a big increase in size.

•74% more for health insurance, even adjusted for healthy family with employer-sponsored health plans.

•52% more for cars, since now we have more cars per household. We gotta get to work, right?

•Infinite% more for childcare (because two people need to work to equal income with the seventies)

•25% more in effective tax rates, due to higher income (two income earners)

Warren also notes that the expenses that have increased are large and fixed. You have to pay rent or mortgage payment whether or not you have a job. You can give up Starbucks or buying new clothes. As for housing size, new houses are for move-up buyers, not first-time buyers, so average size may increase as new houses increase in size, while first-time buyers are taking on the stuff that was produced 40 years ago (and yes, also taking on the increased cost of repairs and maintenance for those houses).

Further, people buy DVD players because it’s much cheaper to buy one and rent movies than it is to take the family to a theater. People also buy DVD players because they have no choice–how many movies are released in VHS? (I wonder if anyone has ever tried to find the point where you’re stuck buying the new technology because a sufficient number of richer people have taken up the newer one. You have to have a cell phone if you do even minimal traveling, for instance, because there are so few pay phones. Or not having a broadband computer connection means that most websites load so slowly that your computer will crash a lot.)

James,

I’m sure you’re aware of the basic bifurcated breakdown of what you listed there:

In the past thirty to forty years commodities we consume have fallen in price. Especially food and drink. Notwithstanding the past few year’s rise this has been a near unbroken general trend since the early eighties. However, assets we must borrow for have risen dramatically in cost. House prices, those for cars, education, etc have all risen in cost. Why? The same thing that drove commodity prices down. Easier credit to large companies has allowed them (along with free trade, a workforce size that has risen much faster than the size of the population it is part of, and changing labor/employer relations) to maximize economies of scale and lower cost. So what happens on the consumer side of things? Easier credit means that you can borrow more for the same monthly payment. In fact, it means every one else can too. Then, there a is natural tendency to borrow as much as you can ‘afford’,(Think of salesmen and the people you know saying, “But you/we/I can afford the payments!”) maximizing consumption. Especially if you have a tendency to see your physical assets as your chief investment as most Americans, and for that matter people, do. (The one exception education loans, have had the same tendency over this same time period. While most people consider this a certification to get a bigger paycheck, save for the diploma it’s not physical.) It’s no surprise that the value for assets such as houses ballooned. Perhaps now we will see a long reversion to the mean in the prices of both commodities and assets.

What does all this mean? Probably that this crisis will not end until the bubble in asset prices and a real possible undervaluing of commodities occurs. Plus, the financial, state, and societal structures that were underpinned by the asset bubble and a world where labor costs were kept low by a dramatically increasing workforce and third world states with and endless supply of cheap labor will have to end or those structures will have to find new ways of paying for everything. That necessarily doesn’t mean an intercontinental revolution or that we’ll have to make do with completely impoverished living for the rest of our lives, but a great many people will eventually go bankrupt. Some things will fail. I don’t see how the euro will survive the decade much less the US trade deficit and its social entitlement programs. Global imbalances will have to either be reduced dramatically or reversed. But in all of this, I see no way to do it prettily. There will be no grand compromise where we find an easy new balance. There is simply too much debt. Someone is going to lose. Someone is going to have to be made to eat their loses or someone else to pay for it. And you can only shove so many loses around for so long. Eventually if you have voters, they vote someone in who will say ‘No’. If you can’t vote…the Egyptians are working on the alternative.

I very much appreciate the numbers and I think they support what I was trying to get across. My generation might not be willing to suffer because of the selfishness of our parents.

Food is less expensive than it was in 1970 (and earlier). But so many other cost have risen, most importantly housing, education, health insurance, and taxes. Incidentally enough, my generation faces rising health care cost and taxes due to the benefits promised to the Boomers. So, we face paying more in taxes to provide healthcare benefits greater than we will enjoy during our lives to people that were to selfish to figure out a way to pay for these benefits for themselves. Taxes rates have risen anyways asides from higher brackets because of the increases in state, local taxes, and the reduction of tax deductions at the federal level (such as eliminating deductions for credit card and car interest payments).

And many of the cost, appliances would rise with an increase in domestic production and you could pile on new cost that can’t be compared across decades such as computers, internet, and mobile phones.

I’ll will find the time to watch the lecture you were suggesting. Thanks.

James,

You say “my generation faces rising health care cost and taxes due to the benefits promised to the Boomers.”

You do realize that’s a talking point right out of Pete Peterson’s playbook, do you not?

DownSouth,

No, I did not know that was a talking point from Pete Peterson. I’ll be completely honest here, I’m 28. I’m not an economist, I’m a lawyer by trade, but I’m working on building my knowledge of economics (that’s one of the reason I come to this blog ;-) )

I looked up Peterson after your comment. So far, I know he was commerce secretary under Nixon and is apparently now a conservative activist. I’ve been accused on NakedCapitalism before of being a Koch troller. I can truly say that I don’t work for any political organization and unless I cite a source otherwise, all my thoughts are my own. (however, correct or flawed they may be)

Many of the prescriptions offered both in these comments, and elsewhere, are well-written and thoughtful but ultimately miss the point that the Kumhof and Ranciere make. There is one, and only one, means of reducing leverage of the bottom 95%: increase worker bargaining power. Debt jubilees, etc. offer temporary relief, but no more.

Please focus your attention on policies that would attain this goal.

@DownSouth. Your comments about the Matthew effect take my breath away. Who is constructing the spiritual foundation that will lead to the rejection of empire? No one I can see. Well, at least some people understand that we need more that a simple “policy” fix.

The resource pie is shrinking overall so giving a larger slice to those that have nothing will be even less acceptable to the rentiers and hegemons. It is such a joke to talk about “regulating” them so they will be fair to the workers.

Ellen Anderson,

The empire need not be rejected. There is another way. The empire needs to be reformed. The empire needs to serve us (the common people) rather than the other way around.

Mansoor

Science calls it equilibrium. Philosophy might call it justice. Economists might call it reversion to the mean.

Regardless, for its survival, capitalistic USA needs to reboot and cleanse. The disparity in pay where the elites and those paid from taxes make an inordinate percentage of the income is unsustainable. When fired bankers receive 47 million in exit pay after selling leveraged CDOs that bankrupted the country, something has to give.

All emotion aside about right and wrong, the system will find equilibrium, and payback to the banks will probably be a bitch through equalizing debt reduction by the masses. (Bankruptcy)

The over creation of credit will insure it doesn’t happen without tremendous volatility and destruction.

Ben, economics is not a science, and it doesn’t care that you received a PhD studying the depression. It has little to do with now.

cswjr said…”increase worker bargaining power’

——

How can this be done when the the person across the table is a hologram thousands of miles away and you have no point of reference to his true location…eh.

Skippy…exercise in chasing tail methinks…unless all wage slaves / labor *globally* are at the same table and at the same time with the capitalists attending in person.

Why do people not understand and why do economists not point out that capital is subject to the law of supply and demand????!!!!!

Those with the supply depend on those wanting to borrow it to maintain the value of that capital. Money is not a store of value. It is a contract. Any value it has is dependent of the sustainability of that contract. When those with money to lend routinely fleece those willing to borrow it, the contract breaks down as surely as a farmer who does not fertilize his fields will eventually have nothing growing, no matter how much seed he plants. As my father used to put it; You can’t starve a profit.