The further you look at the banking mess, the more the same problems keeps staring back: too many losses, not anywhere enough equity or reserves, and a lot of tap dancing by the officialdom to pretend otherwise.

We wrote yesterday, thanks to some sleuthing by Chris Whalen, that Fannie and Freddie might be sitting on north of $100 billion of unreported losses. If they started realizing those losses, one of the first parties that would take a hit would be the private mortgage insurers, since on high loan to value loans (over 80% of appraised value), they were in the business of guaranteeing the loan balance in excess of 80%. So while the failure of the GSEs to act is no doubt part of the extend and pretend shell game, it serves to keep PMIs that would otherwise be as dead as certain notorious parrots alive.

Adam Levitin points to a second and far more important set of beneficiaries from the GSE’s failure to take action on their defaulted loans: the TBTF banks:

…the GSEs don’t seem to be making claims on PMI policies despite being the loss payees. The reason why is that if the GSEs made claims on the PMIs, it would quickly render all of the PMIs not just insolvent, but illiquid (which is the real kiss of death). And if the PMIs went under, then the GSEs would have to take huge write-downs on all of the still performing loans with PMI insurance. Chris Whalen estiamtes that in order to avoid perhaps $100B plus in write-downs, the GSEs are forgoing several billion in PMI claims. If this is the case, it shows what a farce GSE regulation by FHFA is.

There’s a further twist, however, that Yves post didn’t capture. A lot of PMI is reinsured. And guess who does about half of PMI reinsurance? The captive reinsurance affiliates of the large banks.

While most large banks have reinsurance capitves, the captives of the big 4 banks get about 1/3 of all PMI reinsurance premiums, which probably translates to something like 1/3 of the exposure. Just to list the biggest, that’s Balboa Reinsurance (Countrywide/BoA); Bank of America Reinsurance (BoA); Cross Country Insurance (Chase); North Star Mortgage Guaranty Reinsurance (Wells Fargo). I haven’t figured out the extent of this exposure, as not all PMI is reinsured, and not all reinsurance is first-loss position, but there is definitely some bank group skin on the line with PMI.

What this all means is that if the GSEs are forbearing in making claims on their PMI policies, it not only hides the GSEs’ losses. It also means we’re seeing another quiet bailout of the banks.

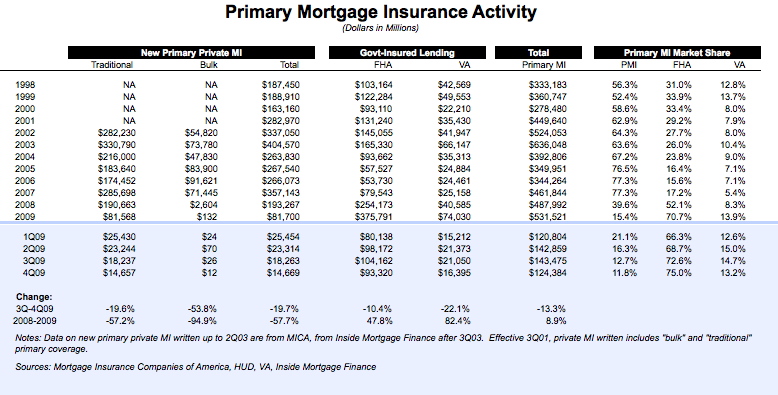

Some readers in the last post asked about the level of mortgage insurance. Levitin e-mailed two sets of spreadsheets; this extract provides an overview (click to enlarge):

Tom Adams concurred with Levitin’s reading:

If Fannie and Freddie are not submitting claims, it helps the banks as much, or more, than the mortgage insurers because the captive reinsurers, presumably part of the banks, held about 50% of the premiums received in a trust. The banks would be responsible for any losses beyond the amount held in trust.

The ceding part is a thorny. There appears to be an interesting asymmetry in the economics versus the accounting treatment which also helps to support the extend and pretend game (insurance experts welcome to correct me if I have gotten this wrong, but I think this is at least directionally correct).

An overview of the captive reinsurers comes in a 2011 report by Promontory Financial (boldface ours):

Instead, most private mortgage reinsurance is written by “captive” reinsurers affiliated with the lender. The mechanics of captive reinsurance are straightforward. The primary insurer “cedes” a portion of the periodic insurance premium to the reinsurer in exchange for the reinsurer’s commitment to share losses. In some cases the reinsurer also pays an upfront fee to the primary insurer. The reinsurer shares losses on either a “quota share” basis (i.e., pro rata) or an “excess of loss” basis, whereby the primary insurer absorbs initial losses and often also subsequent losses above a certain intermediate threshold.

In recent years, excess of loss arrangements were far more common than quota share arrangements. Under a typical arrangement known as a 5-5-25 excess of loss arrangement, the reinsurer receives 25% of the primary insurance premiums, and its obligation to pay is triggered if losses exceed 5% of the primary insurer’s original risk exposure on policies issued in a given year. (The 5% threshold can also be defined with reference to the number of claims filed in a given year.) If this attachment point is met, the reinsurer is responsible for the next 5% of losses. Beyond this detachment point, the reinsurer has no obligation. Beginning in 2008, the GSEs capped the amount of premiums that PMIs could cede under captive reinsurance arrangements to 25% of gross premiums (or gross risk). This move aimed to preserve capital within the primary PMI industry.

Reinsurance does not absolve the primary insurer of its obligation to its insured—that is, the primary insurer remains liable for all coverage if the reinsurer fails to pay.….

PMIs have recently realized material recoveries from captive reinsurance, drawing on (and sometimes exhausting) trusts containing years of premium reserves accumulated by the captives. In consequence, many captive reinsurers are now in run-off mode, and the use of captive reinsurance has fallen precipitously. It is unclear whether and under what conditions the captive reinsurance market will revive.

Now here is the accounting issue, per Tom Adams:

This author suggests that the banks captive reinsurance entities were not reporting future expected losses due to quirks in the structure – they didn’t have any losses until the primary mortgage insurer’s losses were exhausted:

While all mortgage insurers encounter a mismatch between loss reserves and future paid losses, the gap is much more pronounced for lender captives under aggregate excess of loss structures, which cover a book of loans that originate from a ceding company generally over a one year period….

Because these lender captives don’t participate in a loss until a primary insurer’s retention has been exhausted, lender captives are not required to recognize a loss until the cumulative ground-up paid losses and reserves for delinquencies–the incurred loss–exceeds the aggregate loss attachment point.

In practice, this means that under accounting requirements, a lender captive does not have to recognize a loss even if the primary insurer’s incurred losses has reached 99 percent of the aggregate excess of loss’ attachment point and are expected to pierce the contract’s retention. Only when the ground-up incurred loss has reached the lender captive’s attachment point is the lender captive generally required to post loss reserves.

The irony here is that the monolines were done in by mark-to-market losses that were reported way ahead of when they’d actually have to pay claims. Those accounting losses put them in a death spiral because they led to downgrades which both increased their funding costs and killed the ratings that were necessary for them to keep writing new businesses. Here we have mortgage insurers who by any commonsense standards are terminal, and captive reinsurers that are in runoff mode even with the GSEs refraining from putting in claims. Yet both are getting an undeserved stay of execution.

Quite nice, that…

An imbedded antidote.

Having just watched the parrot dilemma for the first time in many years, it is remarkably similar to the way the PTB have handled the whole situation since the crisis.

This is some great reporting and analysis that needs much, much more exposure. I often wondered about PMI insurers but since it was not getting much attention I thought that they had either gone quitely out of business or they were protected in some way and not responsible so I just forgot about them. I really had no idea that the reinsurance was done by the insurance subsidiaries of the lender although it makes perfect sense. I would love to see just how much the average fees, insurance premiums etc. were skimmed out of the average mortgage loan during this whole debacle.

Please continue to pursue and expose this incredible story.

And the icing on the cake is that it was the homeowners that had to pay for the PMI. Privatize the profits, socialize the losses.

I agree that this story seems very important.

In light of the details in today’s post regarding the exposure to PMI losses of the big four banks, who happen to also be the very same big four mortgage servicers, it makes me wonder whether they are acting faithfully on behalf of mortgage bond investors to even make claims for losses that would come out of their own pockets. There is a clear conflict of interest here.

This seems like the basis for a massive class action lawsuit.

Paging all attorneys…gravy train alert…

Seemingly duped into supporting an ongoing Ponzi scheme to enrich a few bank execs and hedge fund managers at all else’s expense, the extent to which the U.S. Gov. has been willing to bend(?) the law to “stabilize financial markets,” is both breathtaking and nauseating. How can we stop this madness?

More shoes dropping.

If this mirrors the monoline debacle, then there’s likely to be a CDS component, as in who was the PMI insurance foisted onto. And how likely is it that that other GSE (AIG) has exposure that may play into the calculations.

Another too intertwined to fail story.

It’s worse than that. Having once worked in that nefarious industry, I can tell you that neither the PMIs themselves nor the lenders thought that the attachment points would ever be reached. These “captive reinsurance” deals were never supposed to be anything more than thinly disguised kickbacks to the banks.

Even after the bubble burst, many of these captives were “unwound” (premium returned to the PMI, and pretend there was never a captive) rather than forced to pay the losses they owed.

The mono lines made a bundle in the 2002-2007 period. It’s hard to lose money in this business if RE goes up a steady 5% per year.

But of course they lost all that and then some since. There’s no question but the these bad boys were a big part of the problem. They got a special carve out from the regulator OFHEO. Fannie and Freddie got a waiver on what was called eligible collateral. They were allowed to fund 100% of a loan as a result.

FHA is sort of a mono line. They guarantee up to 97% of a loan. They have no equity either. They do have full faith and credit of the the US though. Funny that we keep making the same mistakes.

Yves, please investigate more into this. I wasn’t quite up to snuff in understanding this article and i could use a tutorial. I have an excellent credit score (>800) and yet I pay $100 a month in PMI for an FHA, no-down loan. I always thought collateral, fees and an interest rate above inflation took care of the risk. $100 a month seems outrageous but my banker tells me it is an FHA thing. I feel as if my PMI is subsidizing someone else’s bad behavior and is not representative of the risk I represent as a borrower. If I am subsidizing the risk of other modest borrowers I don’t feel as bad (but I am still a bit uncomfortable as i live within my means) but if I am subsidizing an industry that is too cavalier about risk then I am very angry. Should I be angry?

You have an FHA loan w/ PMI? Is that b/c it’s no down payment mortgage? I thought the two (FHA and PMI) were mutually exclusive.

Last week Bloomberg reported on a related piece of this story. Homeowners have sued,and BOA (Balboa/Countrywide) wants to settle for the bogus reinsurance cnarges.

Bank of America Gets Tentative Court Approval of Countrywide Settlement

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-03-18/countrywide-wins-preliminary-approval-of-34-million-settlement.html

From the article:

Three Pennsylvania homeowners alleged in their 2007 lawsuit that Countrywide, once the biggest home lender, required homebuyers who took out mortgages with a down payment of less than 20 percent to obtain private mortgage insurance from a preselected group of providers.

Those providers agreed, in turn, to reinsure the policies with a Countrywide affiliate, Balboa Reinsurance Co. The homeowners alleged that Balboa collected more than $892 million in reinsurance premiums since 1999 and paid nothing in claims. Countrywide was accused of accepting a portion of the premiums and providing no services in return.

Perhaps the policymakers are running out of time and options as the battle for control shifts to the courts.

If the homeowners’ allegation is true, OMG! What a racket!

BoA agreed to pay $34M and admit no wrongdoing. Wonder what that equates to for those covered in the class action–about 3 years of Countrywide PMI people? $10?

Here’s some more background on the Alston v Countrywide case

(Supports Levitan’s kickback scheme conclusion as well)

NOVEMBER 5, 2009 – THIRD CIRCUIT ALLOWS HOMEBUYERS TO SUE FOR KICKBACKS EVEN IF THEY DID NOT PAY MORE – When a class of Pennsylvania homebuyers sued Countrywide Mortgage for allegedly violating the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (“RESPA”) for setting up a captive reinsurance program that amounted to a kickback scheme, the District Court in Philadelphia threw the case out because the plaintiffs did not allege that they had been overcharged. This proved to be short-lived respite, as the Third Circuit Court of Appeals has reinstated the case, finding that the statute intended to allow buyers to recover triple their expenses, even if they did not pay more than would have been the case without the improper activity Alston v. Countrywide Financial Corp., D.C. Civil. No. 07-cv-03508 (3d Cir. 2009).

Homebuyers who put less than 20% down had to purchase private mortgage insurance (“PMI”) in order to obtain financing from Countrywide. The lender referred buyers to one of a list of six insurers on a rotating basis. Those insurers were required to purchase reinsurance from a Countrywide affiliate, Balboa Reinsurance Co..

The suit claimed that this reinsurance purchase was really a kickback, citing Balboa’s receipt of $892 million in reinsurance premiums since 1999 without actually paying any claims. The plaintiffs claimed that this generally raised insurance rates because money was being paid that was not actually based on the taking of a risk, gave the PMI insurers no incentive to compete legitimately to attract customers through lowering the price or improving the coverage and by obfuscating any true disclosure of charges and interest.

Countrywide succesfully gained a dismissal in the trial court based on its argument that PMI rates are set by the state, and that the RESPA statute only allowed a private suit in the event of an overcharge. The District Court stated that the plaintiffs had paid “the only legal rate they could have paid for mortgage insurance in Pennsylvania.”

The Third Circuit disagreed and interpreted the statute to mean that a buyer could recover for three times any charge paid for the improper settlement service, regardless of whether the wrong led to an overcharge. The court also held that the non-monetary nature of the right infringed did not prevent the plaintiffs from having the “injury-in-fact” required for standing under Article III of the U.S. Constitution.

Finally, the court rejected Countrywide’s attempt to use the “filed rate doctrine” as a defense. Although it may not be possible to challenge a rate approved by the regulatory agency, here the plaintiffs were not challenging the rate — they were challenging the kickback scheme.

This decision obviously increases RESPA plaintiffs’ ability to use RESPA to challenge lenders’ activities. However, it is based on the language of this particular provision. In other RESPA provisions, the language of the statute limits recovery to actual damages.

Source:http://www.cwclaw.com/publications/alertDetail.aspx?id=339

On a related note,

This came about as a result of an appeal to the Court of Appeals of a dismissal by the US dictrict court.

Does anyone know if the SEC can appeal the District Court Ruling on the dismissal of the SOX charges in Countrywide case?

how long are we going to stand around and complain about these things. once we learn not to cooperate with them, then we can win. evil can only thrive when good men do nothing.

Avoiding PMI, as a borrower, meant getting a piggy back. Remember them? Subprime pile on!

Can someone with industry knowledge please clarify precisley how PMI policy vests interests?

Who owns the policy? The person purchasing the house or the lender?

Who is the beneficiary of policy? The bank, the borrower or the GSE?

We know the borrower pays the premium.

We know the borrower is the insured.

If the bank is the owner and/or beneficiary of the policy, how is their any transfer of risk?

In response to your comment about accounting, the asymmetry between economics and accounting in this situation does not stem from the accounting standards. It arises from deficient loss reserves (and in some cases premium deficiency reserves). If the accounting standards were applied correctly, the accounting should mirror the economics.

Notwithstanding the accounting standards, the primary mortgage insurers have managed to do a grand job fabricating their reserves. Aggregate excess reinsurance effectively allows crafty management teams to leverage the fabrication. For example, if a primary insurer can get away with understating reserves by 40%, excess reinsurers using similar assumptions might be able to understate their reserves by 75% (until it becomes painfully clear that the aggregate limit will be blown at which point the game comes to an unpleasant end).

If you have any insurance accounting questions, feel free to e-mail me.