By Steve Keen, Associate Professor of Economics & Finance at the University of Western Sydney, and author of the book Debunking Economics. Cross posted from Steve Keen’s Debtwatch.

I initially planned to call this post “Economic Growth, Asset Markets and the Credit Accelerator”, but recent negative data out of America makes me think that this title is more in line with conversations currently taking place in the White House.

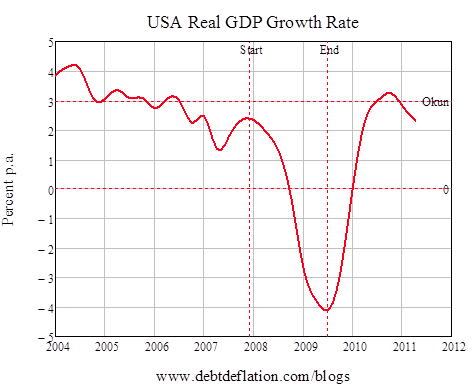

According to the NBER, the “Great Recession” is now two years behind us, but the recovery that normally follows a recession has not occurred. While growth did rise for a while, it has been anaemic compared to the norm after a recession, and it is already trending down. Growth needs to exceed 3 per cent per annum to reduce unemployment—the rule of thumb known as Okun’s Law—and it needs to be substantially higher than this to make serious inroads into it. Instead, growth barely peeped its head above Okun’s level. It is now below it again, and trending down.

Figure 1

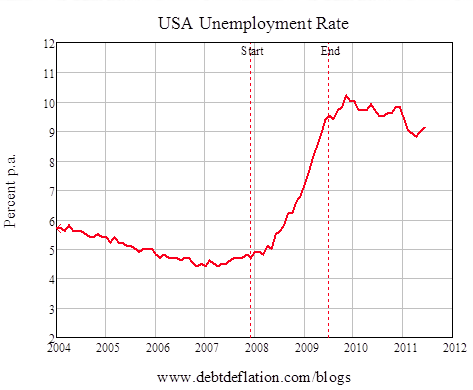

Unemployment is therefore rising once more, and with it, Obama’s chances of re-election are rapidly fading.

Figure 2

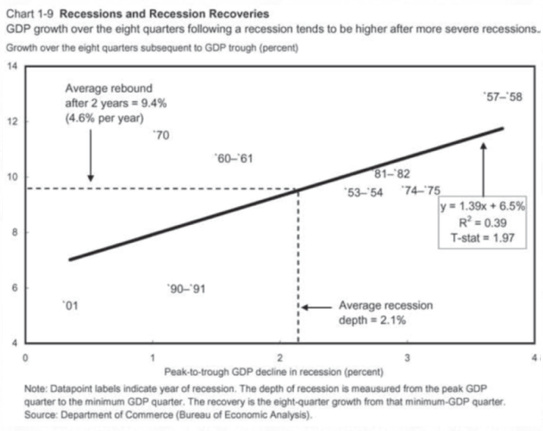

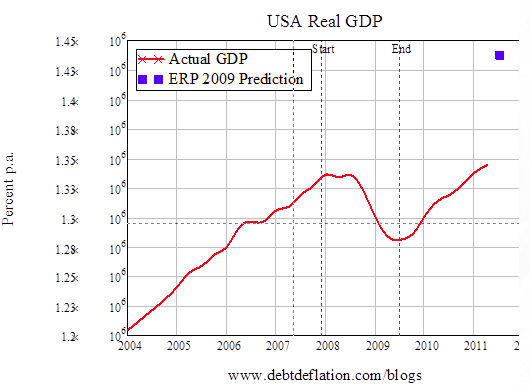

Obama was assured by his advisors that this wouldn’t happen. Right from the first Economic Report of the President that he received from Bush’s outgoing Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers Ed Lazear in January 2009, he was assured that “the deeper the downturn, the stronger the recovery”. On the basis of the regression shown in Chart 1-9 of that report (on page 54), I am sure that Obama was told that real growth would probably exceed 5 per cent per annum—because this is what Ed Lazear told me after my session at the Australian Conference of Economists in September 2009.

Figure 3

I disputed this analysis then (see “In the Dark on Cause and Effect, Debtwatch October 2009“), and events have certainly borne out my analysis rather than the conventional wisdom. To give an idea of how wrong this guidance was, the peak to trough decline in the Great Recession—the x-axis in Lazear’s Chart—was over 6 percent. His regression equation therefore predicted that GDP growth in the 2 years after the recession ended would have been over 12 percent. If this equation had born fruit, US Real GDP would be $14.37 trillion in June 2011, versus the recorded $13.44 trillion in March 2011.

So why has the conventional wisdom been so wrong? Largely because it has ignored the role of private debt—which brings me back to my original title.

Economic Growth, Asset Markets and the Credit Accelerator

Neoclassical economists ignore the level of private debt, on the basis of the a priori argument that “one man’s liability is another man’s asset”, so that the aggregate level of debt has no macroeconomic impact. They reason that the increase in the debtor’s spending power is offset by the fall in the lender’s spending power, and there is therefore no change to aggregate demand.

Lest it be said that I’m parodying neoclassical economics, or relying on what lesser lights believe when the leaders of the profession know better, here are two apposite quotes from Ben Bernanke and Paul Krugman.

Bernanke in his Essays on the Great Depression, explaining why neoclassical economists didn’t take Fisher’s Debt Deflation Theory of Great Depressions (Irving Fisher, 1933) seriously:

Fisher’s idea was less influential in academic circles, though, because of the counterargument that debt-deflation represented no more than a redistribution from one group (debtors) to another (creditors). Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups, it was suggested, pure redistributions should have no significant macro-economic effects… (Ben S. Bernanke, 2000, p. 24)

Krugman in his most recent draft academic paper on the crisis:

Given both the prominence of debt in popular discussion of our current economic difficulties and the long tradition of invoking debt as a key factor in major economic contractions, one might have expected debt to be at the heart of most mainstream macroeconomic models—especially the analysis of monetary and fiscal policy. Perhaps somewhat surprisingly, however, it is quite common to abstract altogether from this feature of the economy. Even economists trying to analyze the problems of monetary and fiscal policy at the zero lower bound—and yes, that includes the authors—have often adopted representative-agent models in which everyone is alike, and in which the shock that pushes the economy into a situation in which even a zero interest rate isn’t low enough takes the form of a shift in everyone’s preferences…

Ignoring the foreign component, or looking at the world as a whole, the overall level of debt makes no difference to aggregate net worth — one person’s liability is another person’s asset. (Paul Krugman and Gauti B. Eggertsson, 2010, pp. 2-3; emphasis added)

They are profoundly wrong on this point because neoclassical economists do not understand how money is created by the private banking system—despite decades of empirical research to the contrary, they continue to cling to the textbook vision of banks as mere intermediaries between savers and borrowers.

This is bizarre, since as long as 4 decades ago, the actual situation was put very simply by the then Senior Vice President, Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Alan Holmes. Holmes explained why the then faddish Monetarist policy of controlling inflation by controlling the growth of Base Money had failed, saying that it suffered from “a naive assumption” that:

The banking system only expands loans after the [Federal Reserve] System (or market factors) have put reserves in the banking system. In the real world, banks extend credit, creating deposits in the process, and look for the reserves later. The question then becomes one of whether and how the Federal Reserve will accommodate the demand for reserves. In the very short run, the Federal Reserve has little or no choice about accommodating that demand; over time, its influence can obviously be felt. (Alan R. Holmes, 1969, p. 73; emphasis added)

The empirical fact that “loans create deposits” means that the change in the level of private debt is matched by a change in the level of money, which boosts aggregate demand. The level of private debt therefore cannot be ignored—and the fact that neoclassical economists did ignore it (and, with the likes of Greenspan running the Fed, actively promoted its growth) is why this is no “garden variety” downturn.

In all the post-WWII recessions on which Lazear’s regression was based, the downturn ended when the growth of private debt turned positive again and boosted aggregate demand. This of itself is not a bad thing: as Schumpeter argued decades ago, in a well-functioning capitalist system, the main recipients of credit are entrepreneurs who have an idea, but not the money needed to put it into action:

[I]n so far as credit cannot be given out of the results of past enterprise … it can only consist of credit means of payment created ad hoc, which can be backed neither by money in the strict sense nor by products already in existence…

It provides us with the connection between lending and credit means of payment, and leads us to what I regard as the nature of the credit phenomenon… credit is essentially the creation of purchasing power for the purpose of transferring it to the entrepreneur, but not simply the transfer of existing purchasing power.” (Joseph Alois Schumpeter, 1934, pp. 106-107)

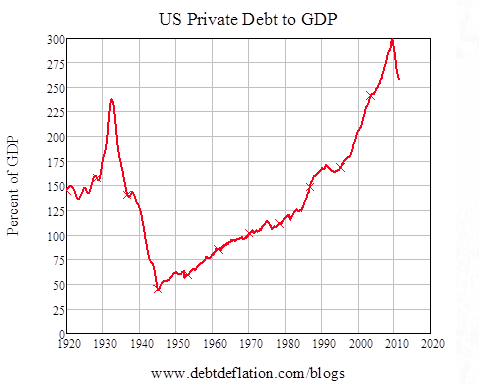

It becomes a bad thing when this additional credit goes, not to entrepreneurs, but to Ponzi merchants in the finance sector, who use it not to innovate or add to productive capacity, but to gamble on asset prices. This adds to debt levels without adding to the economy’s capacity to service them, leading to a blowout in the ratio of private debt to GDP. Ultimately, this process leads to a crisis like the one we are now in, where so much debt has been taken on that the growth of debt comes to an end. The economy then enters not a recession, but a Depression.

For a while though, it looked like a recovery was afoot: growth did rebound from the depths of the Great Recession, and very quickly compared to the Great Depression (though slowly when compared to Post-WWII recessions).

Clearly the scale of government spending, and the enormous increase in Base Money by Bernanke, had some impact—but nowhere near as much as they were hoping for. However the main factor that caused the brief recovery—and will also cause the dreaded “double dip”—is the Credit Accelerator.

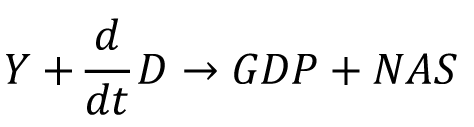

I’ve previously called this the “Credit Impulse” (using the name bestowed by Michael Biggs et al., 2010), but I think “Credit Accelerator” is both move evocative and more accurate. The Credit Accelerator at any point in time is the change in the change in debt over previous year, divided by the GDP figure for that point in time. From first principles, here is why it matters.

Firstly, and contrary to the neoclassical model, a capitalist economy is characterized by excess supply at virtually all times: there is normally excess labor and excess productive capacity, even during booms. This is not per se a bad thing but merely an inherent characteristic of capitalism—and it is one of the reasons that capitalist economies generate a much higher rate of innovation than did socialist economies (Janos Kornai, 1980). The main constraint facing capitalist economies is therefore not supply, but demand.

Secondly, all demand is monetary, and there are two sources of money: incomes, and the change in debt. The second factor is ignored by neoclassical economics, but is vital to understanding a capitalist economy. Aggregate demand is therefore equal to Aggregate Supply plus the change in debt.

Thirdly, this Aggregate Demand is expended not merely on new goods and services, but also on net sales of existing assets. Walras’ Law, that mainstay of neoclassical economics, is thus false in a credit-based economy—which happens to be the type of economy in which we live. Its replacement is the following expression, where the left hand is monetary demand and the right hand is the monetary value of production and asset sales:

Income + Change in Debt = Output + Net Asset Sales;

In symbols (where I’m using an arrow to indicate the direction of causation rather than an equals sign), this is:

This means that it is impossible to separate the study of “Finance”—largely, the behaviour of asset markets—from the study of macroeconomics. Income and new credit are expended on both newly produced goods and services, and the two are as entwined as a scrambled egg.

Net Asset Sales can be broken down into three components:

The asset price Level; times

The fraction of assets sold; times

The quantity of assets

Putting this in symbols:

That covers the levels of aggregate demand, aggregate supply and net asset sales. To consider economic growth—and asset price change—we have to look at the rate of change. That leads to the expression:

Therefore the rate of change of asset prices is related to the acceleration of debt. It’s not the only factor obviously—change in incomes is also a factor, and as Schumpeter argued, there will be a link between accelerating debt and rising income if that debt is used to finance entrepreneurial activity. Our great misfortune is that accelerating debt hasn’t been primarily used for that purpose, but has instead financed asset price bubbles.

There isn’t a one-to-one link between accelerating debt and asset price rises: some of the borrowed money drives up production (think SUVs during the boom), consumer prices, the fraction of existing assets sold, and the production of new assets (think McMansions during the boom). But the more the economy becomes a disguised Ponzi Scheme, the more the acceleration of debt turns up in rising asset prices.

As Schumpeter’s analysis shows, accelerating debt should lead change in output in a well-functioning economy; we unfortunately live in a Ponzi economy where accelerating debt leads to asset price bubbles.

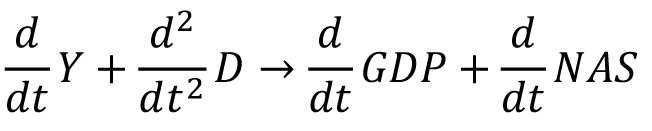

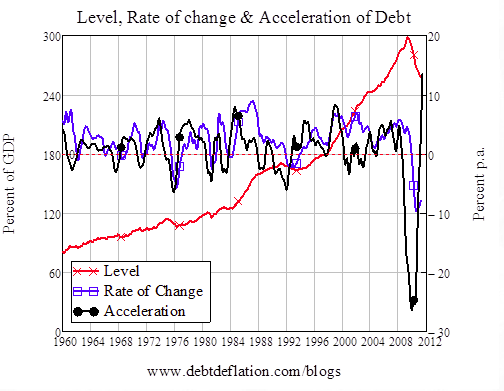

In a well-functioning economy, periods of acceleration of debt would be followed by periods of deceleration, so that the ratio of debt to GDP cycles but did not rise over time. In a Ponzi economy, the acceleration of debt remains positive most of the time, leading not merely to cycles in the debt to GDP ratio, but a secular trend towards rising debt. When that trend exhausts itself, a Depression ensues—which is where we are now. Deleveraging replaces rising debt, the debt to GDP ratio falls, and debt starts to reduce aggregate demand rather than increase it as happens during a boom.

Even in that situation, however, the acceleration of debt can still give the economy a temporary boost—as Biggs, Meyer and Pick pointed out. A slowdown in the rate of decline of debt means that debt is accelerating: therefore even when aggregate private debt is falling—as it has since 2009—a slowdown in that rate of decline can give the economy a boost.

That’s the major factor that generated the apparent recovery from the Great Recession: a slowdown in the rate of decline of private debt gave the economy a temporary boost. The same force caused the apparent boom of the Great Moderation: it wasn’t “improved monetary policy” that caused the Great Moderation, as Bernanke once argued (Ben S. Bernanke, 2004), but bad monetary policy that wrongly ignored the impact of rising private debt upon the economy.

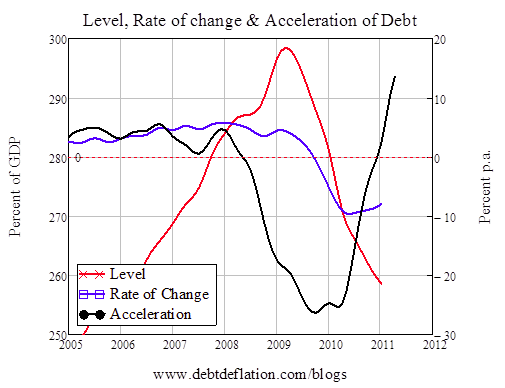

Figure 5

The factor that makes the recent recovery phase different to all previous ones—save the Great Depression itself—is that this strong boost from the Credit Accelerator has occurred while the change in private debt is still massively negative. I return to this point later when considering why the recovery is now petering out.

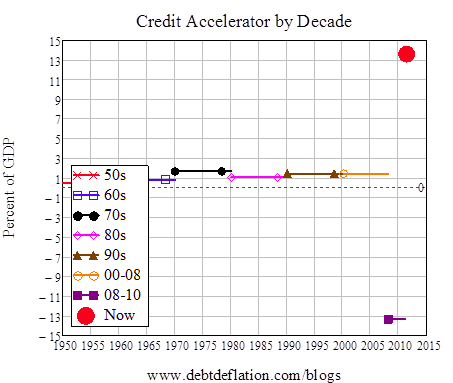

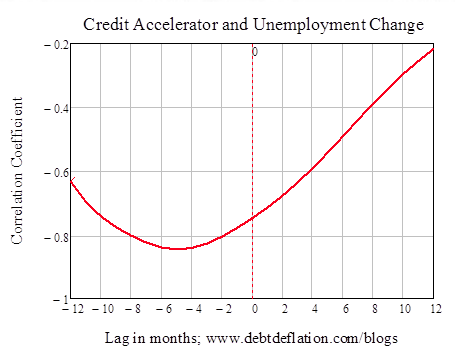

The last 20 years of economic data shows the impact that the Credit Accelerator has on the economy. The recent recovery in unemployment was largely caused by the dramatic reversal of the Credit Accelerator—from strongly negative to strongly positive—since late 2009:

Figure 6

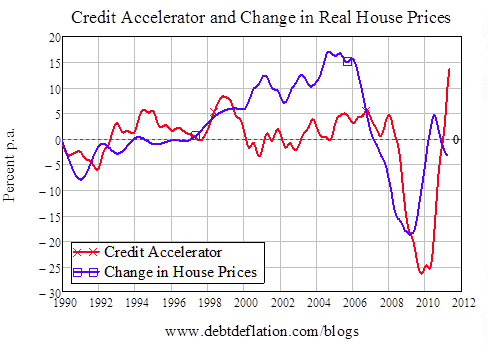

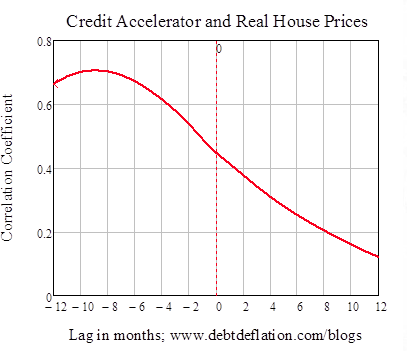

The Credit Accelerator also caused the temporary recovery in house prices:

Figure 7

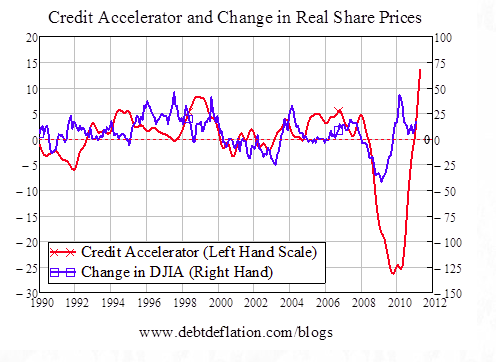

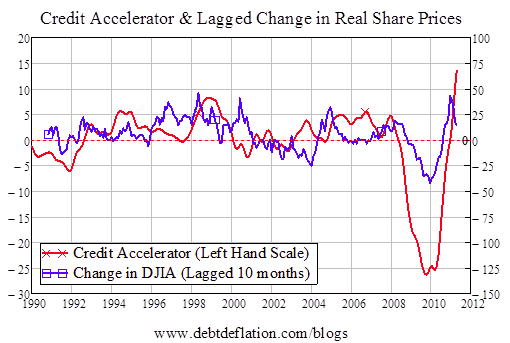

And it was the primary factor driving the Bear Market rally in the stock market:

Figure 8

Leads and Lags

I use the change in the change in debt over a year because the monthly and quarterly data is simply too volatile; the annual change data smooths out much of the noise. Consequently the data shown for change in unemployment, house prices and the stock market are also for the change the previous year.

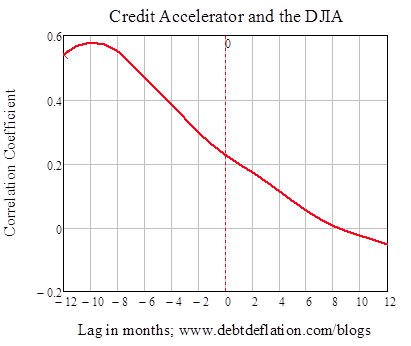

However the change in the change in debt operates can impact rapidly on some markets—notably the Stock Market. So though the correlations in the above graphs are already high, they are higher still when we consider the causal role of the debt accelerator in changing the level of aggregate demand by lagging the data.

This shows that the annual Credit Accelerator leads annual changes in unemployment by roughly 5 months, and its maximum correlation is a staggering -0.85 (negative because an acceleration in debt causes a fall in unemployment by boosting aggregate demand, while a deceleration in debt causes a rise in unemployment by reducing aggregate demand).

The correlation between the annual Credit Accelerator and annual change in real house prices peaks at about 0.7 roughly 9 months ahead:

Figure 10

And the Stock Market is also a creature of the Credit Impulse, where the lead is about 10 months and the correlation peaks at just under 0.6:

Figure 11

The causal relationship between the acceleration of debt and change in stock prices is more obvious when the 10 month lag is taken into account:

Figure 12

These correlations, which confirm the causal argument made between the acceleration of debt and the change in asset prices, expose the dangerous positive feedback loop in which the economy has been trapped. This is similar to what George Soros calls a reflexive process: we borrow money to gamble on rising asset prices, and the acceleration of debt causes asset prices to rise.

This is the basis of a Ponzi Scheme, and it is also why the Scheme must eventually fail. Because it relies not merely on growing debt, but accelerating debt, ultimately that acceleration must end—because otherwise debt would become infinite. When the acceleration of debt ceases, asset prices collapse.

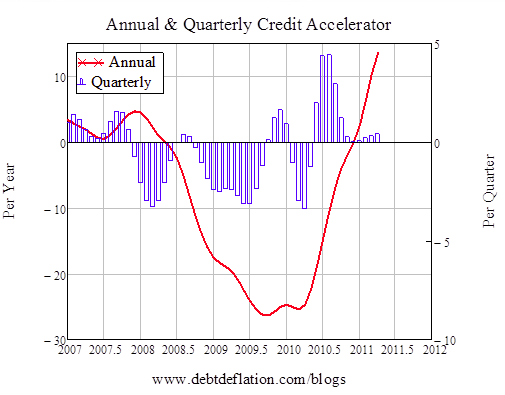

The annual Credit Accelerator is still very strong right now—so why is unemployment rising and both housing and stocks falling? Here we have to look at the more recent quarterly changes in the Credit Accelerator—even though there is too much noise in the data to use it as a decent indicator (the quarterly levels show in Figure 13 are from month to month—so that the bar for March 2011 indicates the acceleration of debt between January and March 2011). It’s apparent that the strong acceleration of debt in mid to late 2010 is petering out. Another quarter of that low a rate of acceleration in debt—or a return to more deceleration—will drive the annual Credit Accelerator down or even negative again. The lead between the annual Credit Accelerator and the annualized rates of change of unemployment and asset prices means that this diminished stimulus from accelerating debt is turning up in the data now.

Figure 13

This tendency for the Credit Accelerator to turn negative after a brief bout of being positive is likely to be with us for some time. In a well-functioning economy, the Credit Accelerator would fluctuate around slightly above zero. It would be above zero when a Schumpeterian boom was in progress, below during a slump, and tend to exceed zero slightly over time because positive credit growth is needed to sustain economic growth. This would result in a private debt to GDP level that fluctuated around a positive level, as output grew cyclically in proportion to the rising debt.

Instead, it has been kept positive over an unprecedented period by a Ponzi-oriented financial sector, which was allowed to get away with it by naïve neoclassical economists in positions of authority. The consequence was a secular tendency for the debt to GDP ratio to rise. This was the danger Minsky tried to raise awareness of in his Financial Instability Hypothesis (Hyman P. Minsky, 1972)—which neoclassical economists like Bernanke ignored.

The false prosperity this accelerating debt caused led to the fantasy of “The Great Moderation” taking hold amongst neoclassical economists. Ultimately, in 2008, this fantasy came crashing down when the impossibility of maintaining a positive acceleration in debt forever hit—and the Great Recession began.

Figure 14

From now on, unless we do the sensible thing of abolishing debt that should never have been created in the first place, we are likely to be subject to wild gyrations in the Credit Accelerator, and a general tendency for it to be negative rather than positive. With debt still at levels that dwarf previous speculative peaks, the positive feedback between accelerating debt and rising asset prices can only last for a short time, since it if were to persist, debt levels would ultimately have to rise once more. Instead, what is likely to happen is a a period of strong acceleration in debt (caused by a slowdown in the rate of decline of debt) and rising asset prices—followed by a decline in the acceleration as the velocity of debt approaches zero.

Figure 15

Here Soros’s reflexivity starts to work in reverse. With the Credit Accelerator going into reverse, asset prices plunge—which further reduces the public’s willingness to take on debt, which causes asset prices to fall even further.

The process eventually exhausts itself as the debt to GDP ratio falls. But given that the current private debt level is perhaps 170% of GDP above where it should be (the level that finances entrepreneurial investment rather than Ponzi Schemes), the end game here will be many years in the future. The only sure road to recovery is debt abolition—but that will require defeating the political power of the finance sector, and ending the influence of neoclassical economists on economic policy. That day is still a long way off.

Figure 16

Bernanke, Ben S. 2000. Essays on the Great Depression. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

_____, 2004. “The Great Moderation: Remarks by Governor Ben S. Bernanke at the Meetings of the Eastern Economic Association, Washington, Dc February 20, 2004,” Eastern Economic Association. Washington, DC: Federal Reserve Board,

Biggs, Michael; Thomas Mayer and Andreas Pick. 2010. “Credit and Economic Recovery: Demystifying Phoenix Miracles.” SSRN eLibrary.

Fisher, Irving. 1933. “The Debt-Deflation Theory of Great Depressions.” Econometrica, 1(4), 337-57.

Holmes, Alan R. 1969. “Operational Constraints on the Stabilization of Money Supply Growth,” F. E. Morris, Controlling Monetary Aggregates. Nantucket Island: The Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 65-77.

Kornai, Janos. 1980. “‘Hard’ and ‘Soft’ Budget Constraint.” Acta Oeconomica, 25(3-4), 231-45.

Krugman, Paul and Gauti B. Eggertsson. 2010. “Debt, Deleveraging, and the Liquidity Trap: A Fisher-Minsky-Koo Approach [2nd Draft 2/14/2011],” New York: Federal Reserve Bank of New York & Princeton University,

Minsky, Hyman P. 1972. “Financial Instability Revisited: The Economics of Disaster,” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Reappraisal of the Federal Reserve Discount Mechanism. Washington, D.C.: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System,

Schumpeter, Joseph Alois. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest and the Business Cycle. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

I’ll be hammering a post hole digger into the ground all day tomorrow. Digesting this tasty post will make the day easier. Naked Capitalism: The Opiate of the Masses.

Dear Paul;

Isn’t the ground a bit soggy up in Joisey to go posting? By hammering, I assume either it’s anger displacement therapy time, or you live on a hill. And digest this post, when you’re going to be working with real posts? You a termite or something? (Couldn’t resist, forgive me.) Finally, NC is more like the Anabuse for these masses. You want Opium for Economists, go see Ryan. He’s your man. (Did you go see Vidal while you were there? That would have made the trip worthwhile all by itself.) Anyway, happy fencing.

The dirt in question is in Colorado, and seems to have missed our wet spring.

Something to whistle whilst you work see:

he’s been with the world

and i’m tired of the soup du jour

he’s been with the world

i wanna end this prophylactic tour

afraid nobody around here

understands my potato

guess i’m only a spudboy

looking for a real tomato

we’re the smart patrol

nowhere to go

suburban robots that monitor reality

common stock

we work around the clock

we shove the poles in the holes

wait a minute

something’s wrong

he’s the man from the past

he’s here to do us a favor

a little human sacrifice

it’s just supply and demand

mr. kamikazi mr. dna

he’s an altruistic pervert

mr. dna mr. kamikazi

he’s here to spread some genes

wait a minute

something’s wrong

he’s a man with a plan

his finger is pointed at devo

now we must sacrifice ourselves

that many others may live

ok we’ve got a lot to give

this monkey wants a word with you

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0UKtZwWLMp8

Skippy…hope it helps, BTW what does your tomato look like?

Your mother picked out a really good name for you.

Keen has been saying this for a while and it makes complete sense to me. The question is how long is it going to take to make this a mainstream position?

Some one from the Ivy league has to adopt this position, publish a few papers and get the Nobel prize a decade hence even as Keen retires from Western Sydney without much mainstream recognition.

I’ve heard Stiglitz say similar things recently. It’s something that bothered me about macro for about 30 years now. But in recent years, now that I’ve chosen leasure over working, I read econ blogs a lot and am finally realizing how dumb economics really is.

Mr Regula;

Shouldn’t that be, “how dumb economists really are?”

I’m sort of becoming friends with some of them. It’s easier, and surprisingly, to get agreement, to just insult the science.

Mr Regula;

You’re right, a blanket condemnation is stupid. My apologies to all.

Econoclasts of the world, unite!

(I love the title, Debunking Economics)

Sir;

I believe that the econoclasts of the world have united, and gone to work for the ECB.

> Keen has been saying this for a while and it makes complete sense to me. The question is how long is it going to take to make this a mainstream position?

When the academic leaders realize they’ve been following a false god it should become quite apparent, since the political leaders get their briefings from those academic leaders. Oh to be a fly on the wall in one of those meetings. Sir, we’ve concluded that ponzi schemes don’t work and we’ll have to maintain two sets of Fed books indefinitely to fool the masses. Oh yeah, we’ll have to draw every business into the conspiracy for it to be effective in allaying complete anarchy.

That’s what obongo gets for putting the same banksters in charge of recovery who created the problem in the first place. What a nice historical legacy.. singlehandedly responsible for collapsing western civilization.

“… the political leaders get their briefings from those academic leaders” only because these political leaders get their campaign contributions from the same people who fund academic chairs in economics. And the people who fund these chairs pick both academic leaders and political leaders who agree with them, no matter how destructive those beliefs are.

In the case of the GOP especially (though not exclusively), they then create and bestow “prestigious” (i.e., lots of money) awards upon their selections to insure that the media can see that their selections are very well credentialed.

Think of it like circus animals doing tricks. The audience may never see the special bowl of oats that Dobbin gets after the show is over, but Dobbin sure as hell knows it’s coming if he gets all of his tricks right.

There will have to be a moment of realization by these charlitans, at some point, that throwing (interest-bearing debt-based) money at this problem is like oil that greases the engine, but it doesn’t provide the fuel for growth.

When that moment arrives I should think there will be a nearly audible gasp coming from the entire Washington collective.

Reinhart & Rogoff: “…what we have really shown here is that severe banking crises are associated with deep and prolonged recessions and that further work is needed to establish causality…” (p. 173)

Doubt I’m the only NC reader who believes that more banking crises are in store before the decade’s gone. Would like to hear opinions on validity of Keen’s analysis when applied to, say, Ireland and Spain.

Even if you disagree with some of the premises, the conclusions are reasonable. Specifically, that QE has funded speculation in commodities and has done nothing to improve employment. Would you care to elaborate on what you think is invalid regarding Spain and Ireland, or is it that obvious?

Where is my Modern Money Theory textbook?

Oh, here it is – a sovereign nation can never go bankrupt.

Now, in a functioning democracy the demostic private sector, i.e the people, is the master and the public sector is the servant.

If the servant can’t go bankrupt, do you think the master will?

Stop worrying about the master’s private debt to GDP.

@MLTPB,

I’m not sure what angle you’re coming at this from. I don’t even know if you’re serious.

But, unless you bail out private debts with public money, there is a difference between private and public debt. Some MMT fans don’t seem to get that.

But Steve Keen isn’t an MMT guy. He’s trying to understand economic reality in view of empirical data instead of trying to fit the data to confirm his theories. I do think what he’s doing could make a difference, but the fact is that he is not as brave as a Keynes, let alone a Henry George, who came before Keynes.

Regardless, the notion that “the people” are the master of our government is laughable. The fact that you argued to the contrary made me assume you were being tongue-in-cheek, that you were using your comment more to criticize the Philip Pilkingtons of the world than to snipe at Keen.

It seems to me the logical application of MMT in the US is just what you “suggest” the use of public debt to pay down private debt, that is a Jubilee. The downside is that it would enable the continuation of all manner of private Ponzi schemes, medical, educational, government services, consumption, etc.

Tao, it was tongue in cheek.

Thanks for the clarification. It is often difficult to tell from the cold text on the screen. There are no other cues to inform the interpretation.

Re: “the deeper the downturn, the stronger the recovery”

==> LOL! That used to work with billions, but no one ever tested that model with trillions!

It should mean that Obama loses the next election but I refuse to think about the alternative that we will be “honored” with……

yves the formulae are in the pdf

http://www.debtdeflation.com/blogs/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/DudeWheresMyRecovery.pdf

Steve Waldman also told me, they are now in the post. Thanks!

They won’t show in RSS, RSS never updates :-(

There is much to like here, but I have to wonder why if Keen can say it is all a Ponzi why he can’t go the rest of the way and call it kleptocracy.

I also find his notion of the Debt Accelerator gimmicky and probably too broad a brush. For instance, how does the Accelerator relate to the Obama stimulus, cash for clunkers, the credit for first time homebuyers, the decision of banks, sometimes voluntarily, sometimes in response to political and legal pressure, to reduce the number of foreclosed homes coming on to the market, and the ZIRP and QE blown bubbles in asset and commodities markets. Now some of these seem amenable to this Accelerator schema and some do not. Also not all of these are the same in the sense that some of these were creatures of the real economy while the asset bubble was part of the paper economy. And the commodities bubble while part of the paper economy still had large scale effects on the real economy.

Keen himself notes that his Accelerator model can’t explain the most recent conditions, except by playing around with it. If I had to choose a central driver behind our economic conditions, I would go for theft instead of Keen’s Accelerator. I tend to view these things in much simpler terms. People are maxed out on debt. The government’s fiscal and the Fed’s monetary stimuli are wrapping up. The various kleptocratic Ponzis and bubbles are consequently running out of juice, and this explains how we can have a deceleration of debt along with declining housing prices and high unemployment.

Oops, I should have said acceleration of debt in that last line, since as Keen says the Accelerator is currently still strong.

A final point: Keen criticizes Bernanke and Krugman for equating debt and assets, but I think he makes a similar mistake with debt. Debt in the real economy seems to work very differently than debt in the paper economy. So all debt is not the same.

Steve Keen: “Unemployment is therefore rising once more, and with it, Obama’s chances of re-election are rapidly fading.”

The “therefore” bothers me. The tight correlation between GDP growth and growing employment needs to be looked into more deeply. Using figures from the ILO’s 2009 Annual Report you can see strong global GDP growth over a decade alongside falling global labour participation rates. We have also experienced flat to falling wages during periods of GDP growth as well as rising ‘natural’ unemployment levels for many decades. Why? Here’s a post attempting to answer this I made a while back (with a couple of graphs!):

http://thdrussell.blogspot.com/2009/10/two-charts-on-technological.html

I won’t address the lump of labour fallacy here (though I will say I believe it debunked) but do want to mention one of my bugbears in this debate about growth, which is technological unemployment. The neat coupling of GDP growth with growing employment does not exist, and the data to demonstrate such a correlation, looking over decades, really isn’t there.

Two things:

1. A for-profit debt-money system will always experience fierce economic oscillations because money expansion and destruction are built in systemically, due to simple things like amortization, debt-build up when ‘growth’ slows or leading to a slowing, and wealth concentration through usury. This oscillation causes the illusion of a GDP-employment bond, but it’s nothing more than the relative availability of credit-money.

2. While we’ve had the surplus energy of fossil fuels we’ve been improving our technical ability to automate/replicate human economic activity. A human being, mere flesh, blood and brain, can only do so much for the economy. This gamut, though in terms of imagination perhaps infinite, is to a very large and growing degree replicable technically. As our ability to replicate and improve on what humans can do economically acceleratingly improves, so the economy’s need for human labour falls. The data strongly suggests something along these basic lines is happening.

Finally, Perpetual Growth, another ‘wonder’ foisted on us by debt-money, is impossible. In the end it’s not economic ‘growth’ we need, but a sensible system which has human and environmental concern at its heart. A system which works for us, not the other way around. In short, until we’ve sorted out the money-system we’ll continue to head over the cliff and experience ever worse crashes, while steadily degrading the natural environment which enables us to perpetuate this suicidal madness, this blind pursuit of ‘growth.’

Toby I think you hit the nail.

Technologically induced unemployment (computers are huge part of this trend), peak oil,rising “useless” production (fake perma growth or GDP for the sake of GDP in best the USSR tradition) as well as “suicidal madness” of the current regime are important factors that we now face.

There might be some way to alter that but it is equally possible that mankind will commit mass suicide.

I doubt whether Steve Keen is as obscure as some people seem to think. I’d be very surprised if Krugman & co. don’t read him.

So why do governments and more prestigious economists not heed his Minsky-inspired warnings about ponzi schemes and over-inflated asset bubbles?

I think part of the problem may be that the gv squid (or “a well known, prestigious investment bank” to those who don’t like Matt Taibi) in its near financial market omniscience can make unheard of fortunes both on the inflation of the asset bubbles and on their rapid deflation. (And even if they do occasionally get caught out they can just ask the government for a donation a la AIG). So with squid alumni at the very highest levels of government, there’s not going to be all that much goverment-sponsored talk about Ponzi schemes, is there?

It would be a shame if the squid takes Western Civilisation down with it (even if Gandhi was a bit sceptical about the term), but as Donald Rumsfeld used to say “shit happens”.

This of itself is not a bad thing: as Schumpeter argued decades ago, in a well-functioning capitalist system, the main recipients of credit are entrepreneurs who have an idea, but not the money needed to put it into action:

[I]n so far as credit cannot be given out of the results of past enterprise … it can only consist of credit means of payment created ad hoc, which can be backed neither by money in the strict sense nor by products already in existence…

It provides us with the connection between lending and credit means of payment, and leads us to what I regard as the nature of the credit phenomenon… credit is essentially the creation of purchasing power for the purpose of transferring it to the entrepreneur, but not simply the transfer of existing purchasing power.” (Joseph Alois Schumpeter, 1934, pp. 106-107) Steve Keen’s post [bold added]

Bull shit! The purchasing power is transferred (stolen) from the general population to the borrowers. Whether or not the “entrepreneur” creates something beneficial to society is irrelevant. And who is to say if it is beneficial? Because it earns a profit? Because the victims of the theft purchase the new products created with their stolen purchasing power? Well, why not? They might as well get some benefit from their stolen purchasing power even if it is illusory. Their birthright is stolen; they might as well eat the pottage they get in return.

It becomes a bad thing when this additional credit goes, not to entrepreneurs, but to Ponzi merchants in the finance sector, who use it not to innovate or add to productive capacity, but to gamble on asset prices. This adds to debt levels without adding to the economy’s capacity to service them, leading to a blowout in the ratio of private debt to GDP. Ultimately, this process leads to a crisis like the one we are now in, where so much debt has been taken on that the growth of debt comes to an end. The economy then enters not a recession, but a Depression. Steve Keen’s post [bold added]

Without a doubt some thefts are less harmful than others but look at the result of even “productive” investments – a dispossessed, unemployed, increasingly vulgar population.

So how can investment be financed without stealing purchasing power? The common stock company is a traditional way. People combine their capital together into a “company” and share from the economies of scale and other benefits of capital consolidation.

There is no recovery because our gov’t took a trillion dollars and wasted it. The stimulus was not properly spent or targeted and the big banks can’t lend because by and large they are technically insolvent. Add to that the dismantling of health care and talk of increased taxes at the worst possible time when the economy is coming out of a deep recession.

There is no recovery because our gov’t took a trillion dollars and wasted it. Conscience of a Conservative

And what is money? Is it not mere book-keeping entries created with a few key-strokes?

We COULD have a recovery but it will take more money creation but this time given to the right people, the victims, not the villains.

There are no quick solutions; Money given to one group of people is taken from another. When I hear about giving money to the “right people” I think of just another attempt at creating a Utopia. this Never works.

I was reading an article on Mamet this morning and was struck by a brilliant quote… “The great wickedness of Liberalism,” Mamet discovered, “was that those who devise the ever-new state Utopias … set out to bankrupt and restrict not themselves, but others.”

There are no quick solutions; Money given to one group of people is taken from another. Conscience of a Conservative

Wrong. 97% of the money supply is so-called “credit” which is actually counterfeit money created by the banks as “loans”. Every month a certain amount of that credit is repayed and thus goes back to nothing. Without additional money or credit added the money supply would eventually shrink by 97%.

So here’s how to bailout the entire population, the victims, without debasing the money supply:

1) Forbid the banks from creating any more “credit”.

2) Every month send every citizen, including savers, an equal check of new, debt-free fiat equal in total to the amount of existing credit paid off the previous month.

The above would eventually replace all “credit” in the money supply with fiat money with no deflation or inflation and eliminate almost all debt.

Utopia may not be possible but justice is. Shame on conservatives for confusing the two.

Beard I’d blow through my monthly allowance in 3 days and I’d be in your front yard asking for a loan. ;)

So you and your conservative friends would have to invent something called a “bank” where you’d store your excess allowance to make money off guys like me. And then you’d invent sub-prime, just for me and my friends down at the pub who take a dim view of “work”. And why should we be wrong for that? What is a human? Something who digs and sweats to serve their alleged masters? Puh-leeze. :)

We’d have a great time together with much back slapping and comraderie, until it became clear I couldn’t ever pay you back.

Ecce Homo, said Fred.

They try to make it a straight line but it’s really a circle, always bending in on itself as it proceeds through time and space.

So you and your conservative friends would have to invent something called a “bank” where you’d store your excess allowance to make money off guys like me. crazzyman

You confuse the loaning of actual money with “credit” creation which is essentially counterfeiting money and lending it out.

And don’t you dare call me a conservative. I am an anti-fascist non-socialist.

sorry, just razzing you. :)

” Absent implausibly large differences in marginal spending propensities among the groups…” Why, exactly would very large differences between the marginal spending propensities of borrowers and lenders be implausible? At some level isn’t the mere presence of money to lend proof positive of a difference in marginal spending propensities? Many keep wondering why in the bubble, the CPI stayed low despite large growth in the money supply. And the answer is that most of that money ended up in the hands of the wealthy, people who have a propensity to “invest.” And by invest, I mean buy equities and financial assets rather than a fourth benz. How can it not be BLINDLING obvious that we’ve been giving Wall Street more money than it can come up with productive uses for. A large proportion of it has bid up the prices of equites and real estate. Even much of the new production of RE has arguably beeen wasted. Empty strip malls are similar to the “dark fiber” of the last boom/bust.

Of course some level of boom/bust cycle is what keeps the economy dynamic. But I would argue that the “great moderation” ensured that instead of small recessions, we’d end up with the “great recession.”

I look at it differently. The difference in marginal propensities showed itself in the debt bubble. We consumed cheap Chinese products(courtesy of Dollar Yuan exchange rates and cheap Chinese labor. The Fed and Treasury abetted by easy monetary policy and credit standards. The Fed could have controlled the process by acting as a regulator and controlled the over leverage in the economy using a wide variety of tools at its disposal. The music went on too long, people and companies drank and danced too much and now we must deleverage.

A different version of the same thing IMHO. The Chinese have a marginal propensity to consume less than Americans. A large part of this is because interventions by the Chinese government, but as some level I don’t think that matters. The effect, a disproportionate ammount of money going to Wall Street and Treasuries, is the same, even if the possible solutions are different. It still tends to make our economy bubblier and less stable than most of us find optimum.

“We consumed cheap Chinese products”

Sorry, but “we” didn’t have a choice. The rich busted the unions, used the Fed to keep wages stagnant since the ’70s on the pretext of fighting inflation, and enacted “free” trade policies. Most Americans had no notion of what was going on and no choice in increasing personal debt and buying from China.

Deleveraging? All that means is that the rich will go to the government to bail themselves out, as we have already seen happen, and the costs of that and everything else will be borne by the ordinary Americans who have already suffered from decades of the depredations of the rich.

The rich did not use the Fed to suppress wages. The Government encouraged credit and low interest rates to promote borrowing to keep the consumption machine going via the housing ATM machine. When you don’t have earnings, use credit I guess.

The government that encouraged credit, is that the same government that is owned by the inherited rich who own the banks, multi-national corporations, etc.?

Please understand that when you say government now you really mean the tool of the inherited rich.

Well when I said “we” I was including the bankers and the politicians who they bought and we elected. But most people certainly DO have a choice to live withing their means. Unless your completely impoverished, there is always somebody who IS living within your means. And yes, a helth emergency can do a number on almost anybody. But the average American who is slowly going deeper and deeper into debt is not the victim of a health emergency. It’s just that their view of what they think that they “need” is more expansive than what they actually CAN afford and they plaster over the difference with credit cards and HELOCs. We rightly ridicule those who object to calling a $250k household “wealthy” because they’re living hand to mouth on an income greater than 80% of US households. But people making $45k are similarly dismissive of those making $60k who are deeper in debt every year. And on down the line.

It is true we have wasted trillions on trinket trade with China but the difference in the Yuan and the Dollar is only a problem because we have a trade deficit. The Chinese say we do not understand their situation which is: if they raise the Yuan many millions of Chinese will be impoverished. They further argue that they are not the sole producers of the products they sell us but instead they buy products and commodities and add to them for export. So their profit is very low as it is. My question is: why have we ourselves suddenly run out of things to make and sell? We definitely have not run out of need. Instead of meeting those needs, we have squandered our money all over the place in too-clever-by-half financial instruments which are now worth nothing yet kept on the books of the banks at full value for the sole purpose of preventing total bank insolvency. And we do nothing about all of this nonsense?

My feeling the Chinese don’t care about profit margins. Their companies actually work on razor slim margins. The Chinese are terribly afraid of revolution and want their citizens employed. With that dynamic American based production is at a huge disadvantage. My guess is that the Chinese are finally waking up to the problems. I predict we’ll see

1) reforms encouraging consumption over savings(e.g. social security) which will encourage imports the local market over exports

2) a very gradual increase in exchange rates. Not to appease the U.S. but to control their domestic inflation.

But these won’t be enough. With the United Stated deleveraging and the U.S. not exactly embracing free trade, we’ll probably see sub-par domestic growth for years to come.

And we do nothing about all of this nonsense? Susan Truxes

It is nonsense. Isn’t it?

But there is a solution – a general bailout and fundamental reform.

So Steve: “It’s the stupid debt, stupid.” That would be the skinny. But I like your thick text approach to putting the debt effect back into macro. A very clear presentation, which means that only economists will fail to understand it. Thanks.

Technical analysis aside, and as one comment stated, theft explains why there is no recovery, and why there won’t be a recovery until fraud and corruption ore addressed. An open system cannot function for long with the aberrations of Congressional corruption and Wall Street fraud. Elections can correct both of these.

It is clear employment has not improved with the $T’s spent on bailing out banks and public works projects, because trickle down economics, i.e. Reagonomics, doesn’t work, not voluntarily, at least. When was the last time GWB ever paid anyone for work who wasn’t a servant?

Where’s Hyman Minsky’s Nobel Prize he was trying to warn everybody about Ponzi finance for many a long year ?

What a beautiful rigorous analysis of the upcoming Wile Coyote moment. Nice mathematical assessment of some of the basic flaws of neoclassical economics and a high dose of common sense relating to our false prosperity. The importance of debt restructuring (abolition) seems the most important battle of the well-functioning economy vs the financial parasitism of the banks with especial relevance in the real estate markets and the Eurozone.

“”Our great misfortune is that accelerating debt hasn’t been primarily used for that purpose, but has instead financed asset price bubbles.”” and not only that but Bernanke sees that as a good thing as it makes us feel better… (also lets some players cash out and makes pension funds etc look better than they actually are)

I have zero economic background (pretty much everything I’ve learned as been via this site)and forgive me if the following question is stupid: Why do we need interest?

It seems to me that money is, at base, not a replacement to a barter system, but a supplement to it that makes it easier to run.

Say I need 10 man years worth of labour RIGHT NOW (for a home, say), so I ‘borrow’ the labour of many people via an abstract representation of that labour, i.e. money, and return it over the span of 10 years.

As similar trade of abstract tokens occurs for different types of labour/expertise, say medical services for car repair.

In a barter system, even one with abstract representative tokens, why is interest needed? Why not just have a central, non-profit bank, that serves as the intermediary for this bartering. I need the money for a house, so I go to the bank, borrow the money (if I’m deemed able to repay), charges me a small admin. fee, and agrees to a repayment schedule.

I borrow 100 000 and payback, say 100 500 (adjusted for inflation), over 20 years. No interest.

Why not? Does interest serve a function I am unaware of?

It keeps old retired people alive.

Common stock as money could serve the same purpose once the counterfeiting cartel and the volatility it causes is abolished,

Common stock, assuming wise management, should only appreciate YOY. The fact that it doesn’t is because of the unstable money that it is priced in.

I subscribe to “old school” risk management, which states if you are retired, and wish to remain so, 20% MAX goes to stocks, and the rest in low risk fixed income.

Unstable money is a problem for anyone. Just ask Brazilians who remember 1980-thru latter 1990 Brazil.

I subscribe to “old school” risk management, which states if you are retired, and wish to remain so, 20% MAX goes to stocks, and the rest in low risk fixed income. Cedric Regula

That has always annoyed and alarmed me that the economy is so unstable.

These past few years have not contributed much to my sense of calm and well being.

But not today. Today is brew day! Cooking up some brew for the warm summer months. Decided on a wheat beer, sort of like a Blue Moon, except better, I’m hoping.

Just tossed some citrusy Cascade hops in the boil pot. Added some dried orange peel and coriander. A touch of lactic acid for tartness. And it smells really yummy.

But back to reality tomorrow when the markets open. Will see again if being out of stocks is starting to look like a good idea afterall. Then that only leaves the fixed income problem.

It keeps bankers alive.

Sometimes it is good to go back to basics.

The two elements you missed (you appropriately identified the third one which is inflation)

– Credit risk : the “many people” who you hire may be justifiably worried that you won’t reciprocate in 10 years time (you may have cancer, a car accident, etc…), so they need to insure themselves against this event, and every insurance requires a premium

– scarcity : there may be not that “many people” available to build your house, because your neighbors may want to build a house too. What will tilt the balance in your favour ? Promise to pay more for the job, but paying in 10 years time, which is again is an element of interest.

Great post.

“They are profoundly wrong on this point because neoclassical economists do not understand how money is created by the private banking system—despite decades of empirical research to the contrary, they continue to cling to the textbook vision of banks as mere intermediaries between savers and borrowers.”

Spot on. The funny thing is that, in my experience, when you press most economists on this point they’ll generally concede to it — and then, straight afterward, forget that they’ve conceded to it.

You go on to talk about monetarism. Well, in my experience economists will generally — note that I say ‘generally’ — concede that monetarism is nonsense and that the central bank only has control over interest-rates and not over the money-supply per se.

Well, my thinking is that once you’ve admitted that, you’ve pretty much admitted that the money-supply is a supply/demand function initiated by banks on the basis of how much the interest-rate is at a given time and the profitability of making a loan at that time.

Not so for most economists. They seem to slip between monetarist logic — assuming that central banks do indeed have control over the money-supply — and the post-Keynesian logic that they don’t and that the money-supply is endogenously determined by the rest of the economy. But whenever you finish the argument they’ve always reasserted their monetarism, even though what they were saying previously flagrantly contradicts it.

In short, their imagination wins out over what they know to be true. It’s weird.

Can we nationalize all the banks in the Federal Reserve system so that we have control over this process? I ask because I’m now wondering about our inability to conceive of a way to resolve TBTF banks. Because banking has now gone international and is so interconnected that their dealings cannot be teased apart. So I guess my question is two part: 1. Could we, currently, tease apart the mess and officially nationalize our banking system, and 2. If we did, what are the foreseeable problems with future situations involving international-national banks. An oxymoron?

Economics consists of a bunch of separate theories often internally inconsistent and often mutually contradictory and often only loosely connected with reality. Economists in their arguments often take snippets from several different theories as if that makes a logical argument. It doesn’t. No wonder economics is confusing. It is confusing because such arguments are inconsistent and lead to contradictions. Economists don’t know how to think very well. Yes it’s weird and very sad.

Agreed!!!

The profits of industrialization was the driver of the Western Capitalist system. Now, in Post-Industrial America, there are few industrial corporations left to produce profits, having shifted this function from the core to the semi-periphery economies, that do the heavy industrial manufacturing and the periphery economies, that do the lowest value added work. We have the most sophisticated form of production, the financialized capitalism of the 21st century. And of course, a de-industrialized economy must be adequately described, explained. The credit accelerator, circulates the needed money for consumer and corporate demand, in lieu of rising wages as a per cent of rising profits. Since over 40% of the wages and jobs came from the manufacturing sector up until the mid-1970’s and now as few as 5% of jobs are in manufacturing, it comes as no surprise that changing facts leads to changing analysis to explain what is going on in the economy. The fact that today, total debt in the US is around $52Trillion, and 75% of that is private consumer and corporate, not government debt, the need for credit is necessary, more than profits and wage increases from profits to expand the economy or just keep it operating.

And since there is an out right refusal, capital is on strike, to reinvest capital in plant, equipment or payroll or public infrastructure for that matter, the credit goes into assets other than the technology industrial complex of modern society. Most of it goes into financial instruments, stocks, derivatives and other stellar innovations, but not material prosperity that can be distributed widely to improve the standard of living for the citizenry. Various asset bubbles of the last 15 years have only served to erode the standard of living for the vast majority of Americans, the 80% who have been downsized, outsourced and temped into 2nd class citizenship, all because they can not trade on Wall ST or maintain high frequency trading server farms that now generate over 40% of all profits and are retained exclusively in the hands of the elite corporate cadres with ever expanding tax cuts, loopholes, and out right removal of wealth off shore altogether.

“In all the post-WWII recessions on which Lazear’s regression was based, the downturn ended when the growth of private debt turned positive again and boosted aggregate demand.”

I don’t think that’s strictly true. I think a lot of the time the key causal factor in these recessions was when the GOVERNMENT took on the debt-load (i.e. allowed public sector deficits to open).

I guess the most obvious of these would be the 1974-75 recession. Minsky discusses this at length in his chapter 2 of ‘Stabalising an Unstable Economy’, the chapter entitled ‘The Impact of Big Government’. Quote:

“In 1975, because of Big Government and the large increase in government debt, the default risk of business and bank portfolios decreased. As businesses liquidated inventories, they decreased their indebtedness to banks and acquired government debt. Banks and other financial institutions acquired liquidity by buying government debt rather than decreasing their assets and liabilities. The public, both households and businesses, not only acquired safe assets in the form of bank and savings deposits, but were able to decrease their indebtedness relative to their income.”

And here’s the crux of it…

“The existence of a large and increasing government debt thus acted as a significant stabalizer of portfolios during the threatening period of 1975.” [P. 41]

So, I think it is this expansion of government debt (clearly seen here: http://bit.ly/j3JO6k) that accounts for the 1974-75 recovery.

Other than that, great article.

Actually, come to think about it, I think that has pretty significant implications for your conclusion:

“The only sure road to recovery is debt abolition—but that will require defeating the political power of the finance sector, and ending the influence of neoclassical economists on economic policy. That day is still a long way off.”

What you should be advocating is an abolition of PRIVATE debt — not debt per se.

Why? Well, I think Schumpeter was wrong — you cannot have a nice stable equilibrium where debt is only used for investment and this investment provides income.

Why? Because all money is debt. And GDP growth tracks debt expansion. That’s what the sectoral balances model quite clearly shows.

For economic growth to take place some party always has to go into debt. This can either be done by running a trade surplus (hence, other countries become indebted to yours), by expanding private sector debt OR by expanding government sector debt.

Without any of these occurring more money cannot enter the economy (remember, you admit that money is endogenous and created by extending loans). So, at least one sector has to go into debt.

Therefore, in order for the private sector to stop running up huge debt-levels, either the country has to run a massive trade-surplus (unlikely in most cases) or the government has to go into debt.

I think that was definitely Minsky’s point. And, since you admit that all new money is debt, it logically follows from your own arguments as the economy cannot expand without new purchasing power — which is: new money — entering from some direction.

And, since you admit that all new money is debt, … Philip Pilkington

Please explain where the debt is if the US Treasury just prints and spends some United States Notes? The only debt I see would be from taxpayers back to government and even then if revenues were less than spending then some money would enter the economy completely debt-free.

That’s called a ‘government deficit’ and that is what I’m advocating. Perhaps you might not refer to this as debt — and you might be right — but in contemporary parlance, this is referred to as ‘debt’.

Okay, so if we just change the terminology and call this a ‘deficit’ rather than debt, the argument remains the same.

If the government runs a deficit by spending it can cancel out private sector debt. However, right now most people would assume that a government deficit is equal to government debt. If it isn’t, then its just a case of changing the nomenclature.

The MMTers are in agreement on this point:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=3346

Yet the nomenclature ‘government debt’ sticks. But it’s just a word.

P.S. Regarding Keen’s article, Mitchell summarises an apt criticism that I have been pretty much engaging in here:

“If you concentrate only on the non-government sector you will make mistakes in inference about private debt dynamics.”

I’ve noticed this in almost all Keen’s work and it puzzles me. He often cites Minsky — but this was front-and-center in all Minsky’s work.

However, right now most people would assume that a government deficit is equal to government debt. If it isn’t, then its just a case of changing the nomenclature.

Philip Pilkington

It’s not a trivial detail; the US government wastes billions on needless interest payments. It’s a sore point with many.

That doesn’t make any sense. You’re contradicting yourself. If this isn’t truly debt then the government cannot ‘waste’ any money on anything.

Interest rates are there to facilitate saving. Nothing more. Some MMTers advocate calling the US ‘debt clock’, the ‘savings clock’. I’d agree.

If this isn’t truly debt then the government cannot ‘waste’ any money on anything. Philip Pilkington

Currently it IS debt. That should be changed immediately. The US Government should cease borrowing forever and save itself useless interest payments.

I think it makes more sense if you say all money is credit. Government spends by issuing credit to people’s accounts. Those people can pass that credit on to others, trade it for things, etc.

Its ultimate value exists because it’s credit against your tax bill. But it acquires many proximate sources of value — you can take your wife out to dinner with it. (But only because the restaurant owner — or someone, eventually — can pay their taxes with it.)

Its ultimate value exists because it’s credit against your tax bill. Steve Roth

True but the banks pyramid greatly (33 to 1?) on top of “government credit” and create their own so-called “credit”. However that “credit” is in other people’s goods and services not the banks’ so it is counterfeit credit. And that is the filthy banker’s game.

On third thought, the only alternative to all this would be extremely low-GDP growth.

If money could only enter the economy via entrepreneurs taking on debt to fund investment, the economy would be forced to crawl at a snail’s pace. Because aggregate demand would be wholly tied to investment.

That works out pretty nice in theory (I would say: Austrian School theory). But it hardly tallies with reality.

First of all, there’s the existence of the government sector — which always accounts for a huge amount of spending. People can complain about this all they want, but to do so is facile — and, I would argue, emotionally determined. They may as well bemoan that we don’t live in a Utopia.

Secondly, there’s the fact that you simply cannot force people into not taking on debt. If the economy was not providing for high levels of employment and sufficient wages to float high living standards (which a purely Schumpeterian economy would not), then people would begin to find their own means of going into debt.

Another way to look at this is that, if people were not able to get access to new money at a reasonably rapid rate, they would simply start creating their own money forms. If new money were only allowed to enter the economy via investment, people would soon grow tired of the low living standards this ensured and start figuring out new ways to take on debt.

The only way to prevent this would be some sort of totalitarian state where people were arrested for creating new money/debt forms. But then, that would result in larger government spending and hence new money entering the economy as the Austrian School government started hiring anti-debt goons! So, it’s not just undesirable, but logically impossible.

Another way to look at this is that, if people were not able to get access to new money at a reasonably rapid rate, they would simply start creating their own money forms. If new money were only allowed to enter the economy via investment, people would soon grow tired of the low living standards this ensured and start figuring out new ways to take on debt. Philip Pilkington

What’s wrong with honest debt? It is counterfeiting via so-called “credit” creation that is the problem. And without government privilege, “credit” creation would be very risky.

We’ve had this argument before. The problem with anarchistic debt creation is that it would be chaotic and ungovernable.

To take a concrete contemporary example, think of the loan shark. We could see Mr. Shark as an heroic entrepreneur extending credit where banks fear to tread. Or we could see him as an abusive parasite who lends to the poor under threat of violence — perhaps even death.

I’d favour the latter.

Plus, there are private money forms such a store coupons, movie tickets, futures contracts, and common stock that require no third party (read banks) debt at all.

We could see Mr. Shark as an heroic entrepreneur extending credit where banks fear to tread. Philip P

That’s already the case; the banks don’t usually lend to the poor. But the banks do drive up prices for the poor with their so-called “credit” creation for the non-poor. Without government privilege for the banks, the poor could save and receive honest interest rates for their savings.

Modern economies require interest-rates for a variety of reasons. Having government issued bonds with a steady rate of interest is imperative for savings, pensions etc.

That we need not refer to these as debt is fine, but their abolition would be stupid. If it ain’t broke don’t fix it.

Having government issued bonds with a steady rate of interest is imperative for savings, pensions etc. Philip P

No they aren’t. But even if they were they should be means tested since government borrowing is a favor to the lender.

And I think you missed my argument regarding the loan shark.

If we were to dismantle the banking system as we know it — completely impossible from a practical standpoint, but however — if we were to dismantle it, my guess is that we’d find a lot more loan shark types that were loaning under dodgy condition and then enforcing these loans with a baseball bat rather than in a courtroom.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/society/2010/jan/27/hard-to-credit-loan-sharks

my guess is that we’d find a lot more loan shark types that were loaning under dodgy condition and then enforcing these loans with a baseball bat rather than in a courtroom. Philip P

Without the banks, most people would not have to borrow. Houses used to cost between 5 and 10 years of saving before the Fed was established.

“Without the banks, most people would not have to borrow.”

You sound remarkably confident in that statement. I would say: far, far too confident.

I think you’re stepping from logical argument to dogma here and I’m not going to pursue this because I’d just end up saying something offensive.

You sound remarkably confident in that statement. I would say: far, far too confident. Philip P

Because banks don’t lend money; they counterfeit it and thus drive people into debt. It is a “Tragedy of the Commons” situation – those who don’t borrow from the counterfeiters are priced out of the market by those who do. So almost everyone needs to borrow so long as banks are free to operate as they do.

But then, that would result in larger government spending and hence new money entering the economy as the Austrian School government started hiring anti-debt goons! Philip Pilkington

Actually, the Austrians are in favour of private currencies although many of them are silly gold-bugs. And the Austrians very much believe in debt; they are devoted to usury.

I’m sure there’s plenty of different ‘strains’ of Austrian School theory. Schumpeter is one (see his Wiki page: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Joseph_Schumpeter).

So, I’m really only referring above to Schumpeter’s theories which, as Keen points out, seem averse to debt not taken out by business owners.

My understanding of the Austrian School more generally is that they favor the Say’s Law ‘supply creates its own demand’ approach. In keeping with this, it seems that they would generally keep to Schumpeter in that they should find consumers taking out debt to be ‘impure’.

But, from what I can see, the Austrian School is a terribly confused bunch without much general consensus. Listening to them is a bit like joining a Marxist-Leninist cell. Everyone agrees on the goal — pure free-market/Communism — but they all have their own ‘interpretations’ on how it should come about.

I believe this confusion and inconsistency is because both schools generally begin with moral considerations rather than looking at reality and go from there. From dreams only dreams will come.

“From dreams only dreams will come.”

Or, perhaps even more to the point: In dreams you walk alone.

I believe this confusion and inconsistency is because both schools generally begin with moral considerations rather than looking at reality and go from there. Philip P

Actually, moral considerations are essential in economics. But the Austrians don’t take morality far enough. For instance, they believe the cure for the economy is a sharp depression – completely ignoring damage to innocents.

The Austrians are thus hypocrites.

“From dreams only dreams will come.” Philip P

That is counter-factual.

“Actually, moral considerations are essential in economics.”

I don’t think that’s true — in fact I was thinking about writing something about this; I might do it next week.

I don’t think moral considerations enter much MMT thinking. It seems to me to be wholly descriptive. Other examples of this are numerous; Sraffa’s descriptions of inputs leading to commodity production seems pretty un-moral too.

In dreams you walk alone. Philip P

Roy Orbison fan?

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zbxsmcT7GOk

Exactly the lyrics I was thinking of — but you gotta accompany them with:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gmsrO8xpe-w

Philip Pilkington said: ” Why? Because all money is debt. And GDP growth tracks debt expansion. That’s what the sectoral balances model quite clearly shows.

For economic growth to take place some party always has to go into debt. This can either be done by running a trade surplus (hence, other countries become indebted to yours), by expanding private sector debt OR by expanding government sector debt.

Without any of these occurring more money cannot enter the economy (remember, you admit that money is endogenous and created by extending loans). So, at least one sector has to go into debt.

Therefore, in order for the private sector to stop running up huge debt-levels, either the country has to run a massive trade-surplus (unlikely in most cases) or the government has to go into debt.”

No! It seems to me by money you actually mean medium of exchange.

There is NO reason (other than the system is set up this way now) the currency printing entity cannot print currency with no bond attached and therefore be the entity that dissaves. That means there is no interest rate attached, no repayment terms attached, and does not bring something from the future to the present.

Savings of the rich plus savings of the lower and middle class = dissavings of the currency printing entity with currency and no bond attached plus the balanced budget(s) of the various level(s) of gov’t

You can also see this post:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=14761

“The best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.”

I don’t agree that is the best way to get more “currency” with no bond attached into circulation, but I admit it is one way.

I think the confusion here is predominantly with nomenclature. As Mitchell points out: government debt is not the same IN ANY WAY to private debt. But it’s difficult to speak about government debt without calling it ‘debt’, because that’s what everyone calls it. Since language is a shared phenomenon, to call it otherwise would be to try to create a sort of ‘private MMT language’ that no-one would understand except fellow ‘converts’ — and that would be weird.

However, the idea that money can be issued without bonds is a bit wrongheaded. If money were issued without bonds in the current setup, it would drive the interest-rate down (I understand that this is not simply a hypothetical and explains why the interest-rate in the US is so low at the moment).

So, under the current system, if a central bank wants control over monetary policy (i.e. if it wants to control the interest-rate) it has to issue bonds. So, money can be issued sans bonds, but to do so the central bank would have to run consistently VERY low interest rates.

So, under the current system, if a central bank wants control over monetary policy (i.e. if it wants to control the interest-rate) it has to issue bonds. So, money can be issued sans bonds, but to do so the central bank would have to run consistently VERY low interest rates. Philip Pilkington

We don’t need a central bank. After the population has been bailed out (all “credit” converted to legal tender fiat) then 100% reserve lending could be practised thenceforth with the interest coming from government deficit spending.

Or if 100% reserves was considered too restrictive then “free banking” with absolutely no government backing could be permitted.

The purpose of central banks is to allow banks to endlessly counterfeit. Who needs that?

Philip Pilkington said: “I think the confusion here is predominantly with nomenclature.”

And, “But it’s difficult to speak about government debt without calling it ‘debt’, because that’s what everyone calls it. Since language is a shared phenomenon, to call it otherwise would be to try to create a sort of ‘private MMT language’ that no-one would understand except fellow ‘converts’ — and that would be weird.”

I have plenty of trouble with that in various other economic blogs. I suggest medium of exchange, demand deposits from debt/loan, and currency with no bond attached. Instead of weird, I call it necessary.

And, “As Mitchell points out: government debt is not the same IN ANY WAY to private debt.”

I disagree with in any way. BOTH private and gov’t debt have an interest rate attached, repayment terms attached, and bring something from the future to the present (time difference between spending and earning).

Some differences:

1)Most of the time the budget of the federal gov’t is set up not to pay interest and principal. This leads to the rollover problems. Most private debt isn’t this way (but some to few are, I disagree they should even be allowed).

2) If the debt is denominated in your own currency and not part of some union (like ECB/EU), then the currency printing entity would be expected to bail out the creditors if necessary. I call that no insolvency, however, most investors and/or ratings agencies would call that a default even though they get their currency/demand deposit back. That would lead to higher interest rates because fewer people would buy the bonds and/or start saving in hard assets driving up their price.

And, “However, the idea that money can be issued without bonds is a bit wrongheaded.”

No it isn’t. It would actually help.

“If money were issued without bonds in the current setup, it would drive the interest-rate down (I understand that this is not simply a hypothetical and explains why the interest-rate in the US is so low at the moment).”

It would not have to. Markup my checking account. Markup the bank’s reserve account 1 to 1. I go to the bank and withdraw the currency. I put it “under a mattress” (figurative). Markdown my checking account. Markdown the bank’s reserve account 1 to 1. Reserve position the same. The fed funds rate the same.

And, “So, under the current system, if a central bank wants control over monetary policy (i.e. if it wants to control the interest-rate) it has to issue bonds. So, money can be issued sans bonds, but to do so the central bank would have to run consistently VERY low interest rates.”

Excluding my example just above about the currency withdrawal and from:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=14761

“The best way to reduce the public debt ratio is to stop issuing debt. A sovereign government doesn’t have to issue debt if the central bank is happy to keep its target interest rate at zero or pay interest on excess reserves.”

Here is bill’s quiz for this week:

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=14869

See Q2 and the Q2 chart about the support excess reserve rate (interest on reserves).