I hate to seem to be beating up on Brad DeLong. Seriously.

As I’ve said before, he is one of the few economists willing to admit error and not try later to minimize or recant his admission (unlike, say, Greenspan). And he seems genuinely perplexed and remorseful. This puts his heads and shoulders above a lot of his colleagues, at least the sort whose opinion carries weight in policy circles.

Even with DeLong making an earnest effort to figure out why he went wrong, his latest musings, via a Bloomberg op-ed, “Sorrow and Pity of Another Liquidity Trap,” show how hard it is for economist to unlearn what they think they know. And as the great philosopher Will Rogers warned us, “It’s not what you know that gets you in trouble. It’s what you know that ain’t so.”

So it’s important to regard DeLong as an unusually candid mainstream economist, and treat his exposition as reasonably representative if you could somehow get his peers to take a hard, jaundiced look at how wrong they have been of late.

DeLong’s mea culpa is about how he and his colleagues refused to take the idea that the US could fall into a liquidity trap seriously. As an aside, this is already a troubling admission, since many observers, including yours truly, though the Fed was in danger of creating precisely that sort of problem if if dropped the Fed funds rate below 2%. It would leave itself no wriggle room if the crisis continued and it had to lower rates further into the territory where further reductions would not motivate changes in behavior. That’s assuming we were in a “normal” environment. But the big abnormality is that we are in what Richard Koo calls a balance sheet recession. And as we will discuss below, Keynes (and Minsky) had a very keen appreciation of the resulting behavior changes, but those ideas were abandoned by Keynesians (it is key to remember that Keynesianism contains significant distortions and omissions from Keynes’ thinking.

But notice how he starts his piece:

There is only one real law of economics: the law of supply and demand. If the quantity supplied goes up, the price goes down…

We’re on target to have $10.7 trillion outstanding by mid- 2012 — doubling the Treasury debt held by the public in just four years. Supply and demand tells us that a steep rise in Treasury borrowings should produce a commensurate fall in Treasury bond prices and thus higher interest rates — and that increase should crowd out other forms of interest-sensitive spending, slowing productivity growth…

Eventually the market’s appetite for Treasury bonds at high prices and low interest rates had to reach its limit, right? Supply and demand isn’t just a good idea — it’s the law.

No, it’s NOT the law, it’s a belief and it often is not operative. I would have liked to give it longer-form treatment in ECONNED, but the discussion there should suffice for our purposes:

But it is actually difficult to prove anything conclusively in economics. In fact, some fundamental constructs are taken on what amounts to faith. Consider the most basic image in economics: a chart with a downward sloping demand curve and the upward sloping supply curve, the same sort found in Krugman’s diagram. Deidre McCloskey points out that the statistical attempts to prove the relationship have had mixed results. That is actually not surprising, since one can think of lower prices leading to more purchases (the obvious example of sales) but also higher prices leading to more demand. Price can be seen as a proxy for quality. A price that looks suspiciously low can produce a “something must be wrong with it” reaction. For instance, some luxury goods dealers, such as jewelers, have sometimes been able to move inventory that was not selling by increasing prices. Elevated prices may also elicit purchases when the customer expects them to rise even further. Recall that some people who bought houses near the peak felt they had to do so then or risk being priced out of the market. Some airline companies locked in the high oil prices of early 2008 fearing further price rises.

The theoretical proof is also more limited than the simplified picture suggests. Demand curves are generally downward sloping, but in particular cases or regions, per the examples above, they may not be. Yet how often do you see a caveat added to models that use a simple declining line to represent the demand functions? Not only is it absent from popular presentations, it is seldom found in policy papers or in blogs written by and for economists. McCloskey argues that economists actually rely on introspection, thought experiments, case examples, and “the lore of the marketplace,” to support the supply/demand model.

DeLong then argues that he and presumably his colleagues ignored the notions of John Hicks, the English economist who formalized the idea of Keynes’ General Theory and turned it into a special case of neoclassical economics. Keynes himself repudiated it, as did Hicks in his eighties.

Why would Keynes not like this treatment? Keynes, himself a successful speculator, did not think financial markets had any propensity to equilibrium, and there is separately reason to think the equilibrium assumption that the discipline has embraced to make its mathematics “tractable” is bollocks. The equilibrium assumption (more accurately, ergodicity) makes it impossible to incorporate any phenomena that are destabilizing, such as ones with positive (self-reinforcing feedback loops. Yet as we discuss short form in ECONNED (and George Cooper gives an elegant layperson treatment in The Origin of Financial Crises: Central Banks, Credit Bubbles, and the Efficient Market Fallacy), financial markets have no propensity to equilibrium. They are inherently prone to boom-bust cycles.

Even though Hicks’ story, via DeLong, bears some resemblance to Keynes’ liquidity preferences idea, it posits different causal channels that render them fundamentally different. In really simple terms, there is a “loanable funds” market in which borrowers and savers meet to determine the price of lending. Keynes argued that investors could have a change in liquidity preferences, which is econ-speak for they get freaked out and run for safe havens, which in his day was to pull it out of the banking system entirely. Hicks endeavored to show that the loanable funds and liquidity preferences theories were complementary, since he contended that Keynes ignored the bond market (loanable funds) while his predecessors ignored money markets.

But that’s a deliberate misreading. Keynes saw the driver as the change in the mood of capitalists; the shift in liquidity preferences was an effect. (In addition, Keynes held that changes with respect to existing portfolio positions, meaning stocks of held assets, would tend to swamp flow effects captured by loanable funds models.)

Making money cheaper is not going to make anyone want to take risk if they think the fundamental outlook is poor. Except for finance-intensive firms (which for the most part is limited to financial services industry incumbents), the cost of money is usually not the driver in business decisions, Market potential, the absolute level of commitment required, competitor dynamics and so on are what drive the decision; funding cost might be a brake. So the idea that making financing cheaper in and of itself is going to spur business activity is dubious, and it has been borne out in this crisis, where banks complain that the reason they are not lending is lack of demand from qualified borrowers. Surveys of small businesses, for instance, show that most have been pessimistic for quite some time.

If you want to put it in more technical terms, what is happening is a large and sustained fall in what Keynes called the marginal efficiency of capital. Companies are not reinvesting at a rate sufficient rate to sustain growth, let alone reduce unemployment. Rob Parenteau and I discussed the drivers of this phenomenon in a New York Times op-ed on the corporate savings glut last year: that managers and investors have short term incentives, and financial reform has done nothing to reverse them. Add to that that in a balance sheet recession, the private sector (both households and businesses) want to reduce debt, which is tantamount to saving. Lowering interest rates is not going to change that behavior. And if you try to generate inflation in this scenario, when individuals and companies are feeling stresses, all you do is reduce their real spending (and savings power) and further reduce demand (and hence economic activity).

If DeLong wanted to treat this issue in their conventional Hicks models, a shift down in the marginal efficiency of capital would be represented as a shift down and to the left of the IS schedule in interest rate/GDP space, not as changes in the slope of the LM schedule, which is what liquidity trap arguments focus on. Rob Parenteau has a very helpful discussion of the shortcomings of the Hicks model in “Employing Krugman’s Cross: Farewell, Mr. Hicks?”

Marshall Auerback, by e-mail, points out that liquidity trap thinking is based on the idea that banks lend out of bank reserves. It has been shown empirically that banks lend first and reserve creation follows (that is, when needed, central banks accommodate loan creation):

The liquidity trap idea seems to be predicated on the silly idea that banks lend out reserves and failure to do so is symptomatic of a liquidity trap. But idea that the build up of bank reserves represent a pot of funds that the banks will eventually loan out completely misunderstands the role of bank reserves. But as Randy Wray, Bill Mitchell, Scott Fullwiler, Stephanie Kelton and a host of others have noted before banks do not loan out reserves. Reserves facilitate the payments system – that is, the system that assures the millions of transactions between banks (as customers write cheques and deposit them throughout the banking system).

Banks do not make loans on the basis of the reserves they hold. They respond to demands from credit-worthy customers and have in mind what it will cost them to make the loans under current conditions. When the transactions that follow the creation of a loan transpire it might be that the is short of reserves to ensure the payments clear. It has various options. It can seek funds from wholesale markets (other banks or other lenders), use deposits (not an overnight option really) or, ultimately, it can source the funds from the central bank.

The point is that you can get various levels of bank reserves depending on how the central bank pursues its liquidity management in order to hit its target policy rate. None of those levels have any particular operational significance.

The mainstream then argue that if the central bank mops up these reserves it will be less inflationary than if it leaves them in the system. This view is based on the spurious – banks lend reserves argument. The inflation risk associated with government spending is the same whether the government issues debt to match its deficit or not. The inflation risk arises from the impact of the spending on the state of capacity in the economy.

This is why fiscal stimulus is vastly more effective than monetary policy at times like these: it has a direct impact on overall conditions, by stimulating demand. Government spending creates more income for businesses and ultimately, consumers. Everyone’s income is ultimately someone else’s spending. If government increase spending, it will increase the incomes of at least some people in the economy, and the improvement in their fortunes (if they believe the new income level will be sustained) will lead them to spend more, improving the affairs of yet more people.

But let’s take DeLong’s supply and demand theory at face value, since it isn’t inoperative, it is just not as neat, tidy, and iron-clad as he believes. DeLong seem to think that there is a discrete market for Treasuries (I’m exaggerating to make a point). But bonds are fungible. While there are some dedicated Treasury buyers, many investors will look at Treasuries as an alternative to other high quality bonds, depending on the yield and perceived risks. And many investors also shift their risk allocations, both from stocks to bonds, and within bonds, from risky to less risky bonds. We’ve seen a far more extreme version of this pattern of late, with a significant proportion of active investors switching from “risk on” to “risk off trades.

So why would investors want more Treasuries? First, in a deflationary environment, the place to be is cash, cash equivalents, and high quality bonds. Deflationary expectations would spike demand for Treasuries. Thus all the austerian policies at the state level alone, which is producing a substantial undertow, would boost demand for Treasuries.

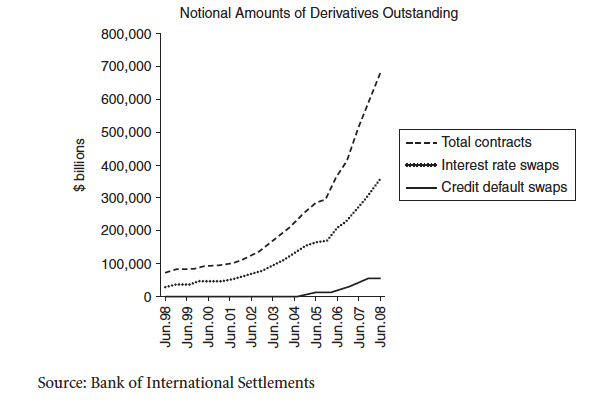

But second, DeLong seems unaware of the fact that there has been a long-standing shortage of collateral for repo. Treasuries had once been the only acceptable collateral for repo. Again, from ECONNED:

Brokers and traders often need to post collateral for derivatives as a way of assuring performance on derivatives contracts…

Due to the strength of this demand, as early as 2001, there was evidence of a shortage of collateral. The Bank for International Settlements warned that the scarcity was likely to result in “appreciable substitution into collateral having relatively higher issuer and liquidity risk.”

That is code for “dealers will probably start accepting lower-quality collateral for repos.” And they did, with that collateral including complex securitized products that banks were obligingly creating.

As time went on, repos grew much faster than the economy overall. While there are no official figures on the size of the market, repos by primary dealers, the banks and securities firms that can bid for Treasury securities at auctions, rose from roughly $1.8 trillion in 1996 to $7 trillion in 2008. Experts estimate that adding in repos by other financial firms would increase the total to $10 trillion, although that somewhat exaggerates the amount of credit extended through this mechanism, since repos and reverse repos may be double counted. The assets of the traditional regulated deposit-taking U.S. banks are also roughly $10 trillion, and there is also double counting in that total (financial firms lend to each other).

In other words, this largely unregulated credit market was becoming nearly as important a funding source as traditional banking.21 By 2004, it had become the largest market in the world, surpassing the bond, equity, and foreign exchange markets.

Now I must confess I have not tried to update the BIS chart. But I have a sneaking suspicion that while derivatives outstandings took a hit in the crisis, between a rise in risk aversion and a concerted effort in credit default swaps land to reduce the notional amount outstanding by netting out offsetting positions, that the old pattern of derivatives outstanding growing more rapidly than the economy has resumed. And now that no one is terribly interested in using AAA rated CDOs as collateral for repo, Treasuries are probably even more important as repo collateral than they were before the meltdown. I’d welcome informed reader input on these issues.

Mind you, it is not as if anything here is esoteric; in fact, it has been said by quite a few economists. It just seems to have no impact on the orthodoxy that dominates policy discussions, even for those like DeLong who recognize that the results of fealty to these ideas have been disastrous.

Awesome.

You are not “beating up” on DeLong. You are presenting a well-thought-out and constructive criticism to something he wrote. In the circles of the very few intelligent people remaining on this planet, this is known as “conversation”.

“As I’ve said before, he is one of the few economists willing to admit error and not try later to minimize or recant his admission (unlike, say, Greenspan). And he seems genuinely perplexed and remorseful.”

Perhaps sometimes. But his representation of Marx is abhorrent:

DeLong’s poorly-researched attack on Marx

Kapitalism101’s great rebuttal

Take this bit from a lecture of his on Marx: “[Marx thought] that even though the ruling class could appease the working class by using the state to redistribute and share the fruits of economic growth it would never do so”

Of course, this is a complete fabrication – Marx himself documents much of the laws that have come about in order to stabilize capitalism and placate workers in the first volume of Capital.

Now don’t get me wrong – DeLong is a capable economist. He is worth reading. But don’t expect him to admit fault when he is criticizing capitalism’s punching bag. There’s no incentive there.

It is painfully obvious Yves you are not an economist. You show a fundamental misunderstanding of what economics is all about. You deal in fact and truth whereas economists deal in wishful thinking and truthiness.

There is no need for DeLong to respect facts; economists need only hew to their ideological dogma as tools for rich people. If they put on a show of being humble or willing to learn from their mistakes, you must thank them for such a virtuoso performance. Then give them a Nobel, err Swedish Riskiobanks Prize.

Facts are not important because they are transitory.

Which is also why we needn’t bother with climate change–it’s about weather, which is transitory. And humans, being both fact and transitory, are doubly unimportant…

Thanks to my recent study of economics, I’ve begun to see that civilization has never been more free…

“Companies are not reinvesting…”

The heart of the problem. Money has become the end goal instead of the means. If they aren’t investing and producing and growing the economy, there’s no point in pushing more money at them. Put the money in the hands of the people who need it and will spend it. That’s why all the deficit reduction talk is just idiotic right now, as Krugman keeps pointing out. We don’t have a deficit problem, we have a GROWTH problem.

If government increase spending, it will increase the incomes of at least some people in the economy, and the improvement in their fortunes (if they believe the new income level will be sustained) will lead them to spend more, improving the affairs of yet more people. Yves Smith

The most morally obvious solution since the banking system has cheated both savers AND borrowers is a universal (all US adult citizens) bailout of the entire population. And that bailout need not be inflationary if further credit creation by the banks was outlawed and if the bailout was metered to just compensate for the decrease in the money supply (reserves + credit) as existing credit was repaid.

The issue which has swept down the centuries and which will have to be fought sooner or later is the people versus the banks. Lord Acton

I wish there were a way to go back and claim damages. Calculate every penny of abuse we have suffered. Get triple damages. But we have lived naively with a system that betrayed us. We have no laws to claim that we should have had decent jobs since 1995. Or whatever. Healthcare. You name it. All we can do legally is go forward. To that end, a proclamation by an entirely new government could make us all whole. Short of bloody revolution, it will not happen.

Short of bloody revolution, it will not happen. Susan the other

It might happen. If a universal bailout can be accomplished with no inflation risk then who can object? A universal bailout would fix everyone, including the banks and savers.

But I don’t doubt that more heat might be required before some people see the light.

I’ve never read, in my history books, about an occasion where entrenched wealthy power has willingly given up position (mere position–not talking about money) without revolution, which have usually been, but has not inevitably been, bloody.

But maybe that’s what you mean by “more heat”.

what is it that the savers have to gain again? are they going to get a pile of money to compensate for not having the foresight to become leveraged?

what is it that the savers have to gain again? spooz

A monthly bailout check like everyone else till all the “credit” in the system was replaced with fiat.

Can’t teach an old dog new tricks is the folk wisdom concerning conventional economists. In physics it is quipped that the field changes one funeral at a time. If economics is, as I believe, more akin to astrology than astronomy, even funerals may not help. Astrologers functioned as the court apologists. Today, economists provide the words that coat the gut level, self-serving decisions of the rich and powerful with a patina of intellectual respectability. Not much difference really. The only economists who will be invited to power lunches are the hacks like Friedman who support theories resulting in the stink of pant leg urine. And look at cretins like Ayn Rand – not an economist even, yet she is holy writ to a large segment of the Nouveau Riche. I’d bet you’ll find her books on the butcher’s boy Lloyd’s bookshelf. And I’ll further bet he consults it as he “does God’s work.”

My opinion is that it really doesn’t matter if DeLong comes to his senses or not. If he does he will be cast to one of the outer rings of hell where he can chat with the likes of Steve Keen. There will always be new hacks ready to take his mantle and speak for rather than to power.

The inflation risk associated with government spending is the same whether the government issues debt to match its deficit or not. The inflation risk arises from the impact of the spending on the state of capacity in the economy. Marshall Auerback

If so, then there goes the last excuse for US Government borrowing.

“Consider the most basic image in economics: a chart with a downward sloping demand curve and the upward sloping supply curve… one can think of lower prices leading to more purchases … but also higher prices leading to more demand.” Yup: that was discussed in the first Economics lecture I ever attended. Anyway, I don’t understand your weakness for Broad DeLarge – his censorship on his blog is pretty disgraceful.

“his censorship on his blog is pretty disgraceful.”

Yep. He censored anyone he strongly disagreed with, left or right, regardless of their civility etc. That’s the main reason I quit reading his blog.

As I said, he looks good relative to his peers. Remember, Larry Summers got the transcript of the Jackson Hole session at which he called Raghuram Rajan a “semi-Ludddite” (which has been reported by people in attendance) changed to “semi-Leddite” to cover his tracks. So not only is Larry corrupt, he’s petty and preening too.

I don’t see how the definition of a liquidity trap is based on the notion that banks lend reserves. Granted I’m not an economist, but at least Krugman claims these days that “my definition of a liquidity trap is, purely and simply, a situation in which conventional monetary policy — open-market purchases of short-term government debt — has lost effectiveness. Period. End of story.” (http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2011/07/05/whats-in-a-name-reposted/). In fact the wikipedia definition specifically states “Liquidity traps typically occur when expectations of adverse events (e.g., deflation, insufficient aggregate demand, or civil or international war) make persons with liquid assets unwilling to invest” which seems to be in line with what Yves is saying…

Also this phrase seems like a simplification: “And if you try to generate inflation in this scenario, when individuals and companies are feeling stresses, all you do is reduce their real spending (and savings power) and further reduce demand (and hence economic activity).” Yes cost of living goes up but their real debt burden decreases as well and if inflation entices the players who are not highly indebted to pick up some of the slack while their counterparts repair their balance sheet it could be beneficial. I agree that fiscal policy is preferable and I also agree that conventional channels with which monetary policy usually operates are limited (i.e. interest rates), but I think the inflation argument has a little more merit than you give it credit for.

Two cases where the law of supply and demand become perverted:

1) Debt. Debt can be packaged up and sold without reflecting supply and demand dynamics. In the case MBS’s, the price of debt instruments were completely disconnected from the supply of debt. Liar loans were created to fill the demand for debt. The bubble was not in the debt, but in the price of housing.

2) Hedging. A hedge is designed to limit loss, not make money. Any time a hedge exceeeds 100%, then that signals waste, and gross distortions manifest. Example: having enough nuclear weapons to blow up the world is a 100% hedge. Having enough to blow up the world 10 times is a waste. Example 2: Having more value in insurance policies than the value of the insured item actually favors the destruction of the item. Add TBTF into the mix, and watch the perversion of prices ensue.

Capitalism has (d)evolved from a theory of efficient markets to the production of capital for its own sake.

It really doesn’t matter that there are cycles within any system. They are fundamental to the existence of the system. The happy medium is equivalent to a big flatline on the heart monitor. If the system seems to be getting out of whack, it is only feeding a bigger cycle.

As you point out, someone’s spending is another’s income and someone’s borrowing is another’s investment. That is the real law of supply and demand, applied to finance. Capitalism finds it can create its signature product, capital, by creating demand for it. Borrowing. Now there is too much bad debt and the entire economy is being railroaded into maintaining the value promised the investors in this “demand.”

The fact is that money is a contract, not a commodity. If you hand someone a piece of paper which is written, “This is redeemable for one ounce of gold,” that piece of paper is a contract, not a commodity. It is NOT a store of value. It is a PROMISE of value. Money really is only a medium of exchange, not a store of value and as such it is the property of that institution which guarantees its value. Just try printing some up, if you want to find who holds the copyright.

If people understood money constitutes a form of public property, they would be far more careful what value they convert into money and would quickly learn to put value into other forms, such as social connections, health and environmental sustainability, rather than draining it out of these organic functions, to store in the banking system.

Thank you, wonderful comment, I understand things a little better now.

Count me in the ‘Amen Choir’.

It did during the Volker years when the corporate prime rate was 12% and no one could get their ROI calculations to yield a positive number.

But then in dot.com times you didn’t need to borrow money. You could just do a IPO for free. Also, “stock investors” had no problem with borrowing at a 8-9% broker margin rate to chase hot stocks with 20-100% returns.

So that’s the kind of “deadband” we have with monetary policy.

I said “usually not the driver” :-)

A prime rate of 12% is not usual.

I know you know that. I was just trying to point where we get the extremes.

The mystery of the Volcker years is that inflation is caused by loose money policies, but tight money policies only serve to harm the demand, the borrowers, not the supply, those with money to lend.

The high interest rates preceding Volcker’s term were due to investors spending their capital, rather than lending it, so there was a shortage of money to borrow, but too much in the regular economy.

So how is it that he cured inflation with higher rates, when that further hurts demand, while rewarding supply?

If he sells debt, he’s simply increasing the return to investors for surplus capital. That doesn’t increase productive demand for it.

It just so happened that Reaganomics served to seriously increase the Federal deficit at the same time. Not only did this serve to draw out far more capital from the markets than the Fed’s actions, but the money was spent back into the economy in ways which also served increase private sector investment. I think it has been the deficit which has served to keep inflation under control and it was always thus. Volcker’s actions were only a smoke screen.

Mr Leaves;

Another “Amen” to that.

My imperfect polling data from the couple of small business owners I know shows an ‘aversion to risk’ of a high order. All of them tell me of falling consumer demand and tightening of requirements from suppliers, (higher cash requirements and quicker credit repayment terms.) All of them are tightening up credit terms for regular customers. There’s something trickling down from above, bit it doesn’t smell like money.

Well, I was wondering when economists would come up with a new theory to explain why I spend less money when I try and live off of ZIRP income. Thanks for the gentle nudging Yves.

I see we are treated again to the the beady eyed insights of Auerbach and the MMT bean counters.

They just about had me convinced that loans precede reserves, because Ameritrade, my broker, swept all my funds into their Canadian parent bank. So if anyone wants a loan in America, certainly US banks will have to ask a foreign bank for reserves… or maybe the Fed, as lender of last bailout.

But then I recall seeing some data that says the Fed has something like a trillion in excess reserves! Doesn’t this turn MMT on it’s head, because now banks have the reserves first and the loans would follow?

Then the way I’ve heard the rest of the MMT story, the economy, financial and tax system would need to be re-juggled as well to resync with this flip. Kind of like trying to turn a bunch of mobius strips inside out? Won’t that keep them busy a while?

Agree about the New Keynesians tho. What are our other choices? Well, never mind.

It has been well demonstrated empirically, long before the crisis, that lending is not constrained by reserves. This isn’t theory. The New Keynesians (who are really more like Old Keynes, and it’s New Keynsians, not MMT, that came up with this) developed the data and the theory. When banks can’t get reserves from other banks, the central bank will accommodate them and create more reserves. Otherwise it can’t maintain its policy rate.

The notion that reserves generate lending is just weird. Put it in investment terms. It’s like saying money burns a hole in your pocket. If you had $100 million dollars. you don’t invest it just for the sake of being fully invested (unless you are day trader junkie type, and they aren’t investing per se). You invest because you think you have realistic odds of making a return. If you don’t see enough opportunities you like, you’ll have uninvested funds (which you might hold in cash, money market fund, Tbills, whatever your preferred short term stash medium is).

You are are being too serious today!

In manufacturing we used to say “get the biz first, then we’ll ship the product.”

Everyone new that when banks run the free toaster ad it means they need money to pay someone off.

Actually, it’s the Post Keynesians that are like “old Keynes” and understood reserves do not constrain lending, along with French Circuitistes. New Keynesians are orthodoxy, like Mankiw and Taylor, which is a complete bastardization of Keynes, and they’ve obviously no idea how banking works.

Whoops, sorry! You can tell I don’t take these doctrinal disputes as seriously as I ought to.

All you need to know is when you see the free toaster ad, the FDIC will shut them down a week later.

It seems to me that economists would be a fruitful area of study for sociologists, psychologists, cultural anthropologists, etc.

Does anyone know of any such studies?

Columbia’s Jon Elster, who is a political scientist, has written about this topic: “Excessive Ambitions,” in Capitalism and Society.

http://www.bepress.com/cas/vol4/iss2/art1/

Well, this is another article I’m going to read four times to understand. Christ, I learn a lot here. Thank you, Yves.

Dear MRW;

Hooray! Someone else who re-reads the articles several times to find enlightenment. I’ve always said Mz Smith runs a public utility here. Maybe, an educational institution is more accurate.

Thank you maam.

The confusion is a result of our approaching what is at long last the end game for both fiscal and monetary policy. The policy options available to the various economic policy actors are finally dramatically proscribed/prescribed by facts on the ground. Policy makers finally must choose:save/defend their currency (pound,euro,dollar)or save the banks. The time for temporizing, and theorizing is past. It’s crunch time. Personally, I think governments will throw the banks under the bus when the real prospective risk of imminent currency collapse sinks in.

I don’t know if it’s the end game. The last resort of policy-makers is simply to lie (as we saw yesterday from Trichet and his edict about Portugal’s ratings), and this could go on for a very long time. This is a very publicly understood lie, and enforced by the highest echelons of government power.

That we have gone over the edge into the abyss is understood by everyone. When we scream bloody panic is really the only question.

Agreed. But lying is not a policy strictly speaking. Print/don’t print, and spend/don’t spend are policy options. Not so good to be the king these days.

“I think governments will throw the banks under the bus …”

That would be contrary to everything we’ve seen for a long time. Personally I think we’ll see pigs fly first.

As Steve Keen points out, in terms of money printing to save the banks, you ain’t seen nothing yet. The marginal printing required to deleverage the U.S. private sector by half is $42 trillion. It’s not the years, it’s the milage. What governments have the belly for that?

This is a silly post.

The fact that there are Veblen Goods (those items which experience greater demand when price goes up) does not mean there is no law of Supply and Demand.

As the price goes higher on a luxury item, it suggests exclusivity. Exclusivity is to the wealthy man what scarcity is to the poor one. Either way, supply considerations are implied….

It’s just that with a status purchase, like a $20,000 Rolex, the purchaser is concerned with the supply out in the general public, as opposed to with the Seller. Furthermore, unlike the “scarcity” purchaser, the “exclusive” purchaser is NOT concerned that he will NOT get the status item. Rather, he is concerned that others will get that item. Again, supply influences demand, even if it’s a bit distorted.

And just because there are temporary deviations of a law, it does not necessarily mean the law doesn’t exist. Yves’ thesis makes about as much sense as stating that the fact airplanes can fly means there is no gravity.

I follow Dan here… while trying, and failing mostly, to follow YS. It’s me, sans doubt.

I don’t see a problem with DeLong’s solution of deficit spending. After all, that’s probably what will help kickstart demand. It’s just that he’s right for the wrong reasons.

Krugman himself stated that the demand curve doesn’t always slope downward, in a talk he gave at the LSE in 2009. Also, his definition of liquidity trap doesn’t seem to be predicated on bank behavior, but on real v. nominal interest rates.

I’m not sure DeLong is unaware about the desire for repo collateral. I think he just doesn’t really care. He sees the demand for Treasuries outstripping supply, and never mind the why. As a former White House staffer, he is going to focus on the policy prescription (rightly or wrongly). If you think that the reason demand is up matters, and that the reason is repo, what is the policy recommendation — outlaw repo? Remove all limits to FDIC protection? Or just make more Treasuries, regardless of what is driving the demand?

It is not that Delong does not get it, he logic is based on poor scholarship.

Neoclassical economic theory is wrong due to the foundation of its principles:

– Treats complex monetary exchange as barter

– Assumes macro economy is stable

– Ignores social class

Treats entire economy a single agent

– Obliterates uncertainty

“Rational” as capacity to foresee the future;

– Uses empirically falsified “money multiplier” model of money creation; and

– Ignores credit and debt.

If Delong was willing to shed the junk economics from his mind, he could get to the right answer.

Put simply, the post says that few economists know much about finance. I think that’s true. Keynes knew more than most, partly because of his personal involvement in markets (he wasn’t always a successful speculator, by the way; he got his fingers burned sometimes), and partly because of his involvement with the insurance industry.

You can get a degree in economics without doing many (perhaps in some places, any) finance courses, and even the courses some economics students do take probably aren’t worth much in terms of understanding the world.

Economists tend to justify their ignorance of finance by saying that economics is more important and will swamp purely financial things in the end. Well, “in the end” is too late for most people, and anyhow it isn’t that simple. Economics (as traditionally defined) and finance are more like dance partners than some kind of master-slave relationship. A good dancer can steer his/her partner anywhere on the floor he/she likes. Which would indicate that financiers are better dancers than economists are. Maybe that’s because the economists think they’re dancing with a dummy.

I too am a Richard Koo believer. This “balance sheet recession” is not just in America, but in Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Spain and England based on real estate speculation.

As seen in Japan it is a very long wind down to get the balance sheet in order especially when their is complete denial in writing down the debt along with the zombie banks. The austerity measures imposed by the governments is the wrong answer and will exacerbate the problem.

His book “The Holy Grail of MacroEconomics” is a must read.

For those waiting for the 5% GDP growth rebounding out of a recession they will be waiting along time expecially given the lack of fiscal stimulus.

A one percent return in todays enviroment is a great return as asset bubbles continue to deflate.

Rock on Yves!

Yves,

Poor DeLong does not understand that you are being nice to him…….

Thanks.

Yes, about time someone called these bastards for what they are: Vichy.

And lest we forget the exemplar, here’s an excerpt from Ophuls’ 1969 documentary Le Chagrin & La Pitié (The Sorrow & The Pity), part of the famous interview with the French aristocrat who, even after having been contacted by the Maquis (the active French resistance), and knowing of Jewish deportations from France, thought the more obvious move was to join the Waffen SS on the Eastern front:

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6qsOH1ALlSo&feature=related

Essential viewing.

I thought DeLong was barking up the wrong tree entirely. The liquidity trap occurs when the returns on substitutes for money like bonds are so low that money itself gets hoarded as a secure investment, rather than being used in transactions, hence economic activity declines. The key point is that money is special, because it is the medium of exchange. Conventional monetary policy easing operations involving buying bonds are ineffective at boosting the circulation of money because they simply switch two close substitutes. Such a liquidity trap ought to be characterised by deflation, which the US is not presently experiencing.

In his Blooomberg piece DeLong opines, “The demand for Treasuries was inordinately high, in part because the supply of alternatives was low. Lacking confidence, corporate executives held back investment…”

So it’s all about confidence? Really? For the economics-as-theology-and-never-mind-the-facts set ‘confidence’ is a preferred way to sustain the narrative and segue gracefully past unsupported logical jumps. Which is not to say that it’s not genuinely believed by many that invoke it. But then, many true believers really did think the world was going to end a couple of months ago.

As an alternative, what about “corporate executives held back investment because too many of their customers had been wiped out by their own bad investments and were drowning in a sea of debt”? Yes, it’s a balance sheet repression.

But, starting from a narrative spun around confidence, most effort has been put into recreating confidence, an approach that naturally appeals to PR obsessed politicians. Unfortunately for them, and consequently for the rest of us, saying (and even believing) it’s about confidence don’t make it so.

Defective here…Capital used to create jobs, expanding credit, spending et al, increasing Capital. That got old, so it started to fold in upon its self, cold dark for everyone else save the singularity’s core, volumes fiat friction heat is but a poor campfire to stave off a chill, save I/CB hearts, if they had one, more like slowing rigor mortis effects (any one got a thermometer, yeah I know, they will just light a match).

Skippy…how do you unpack, unfold a dark matter singularity…and…should you…if you could? A New Universe is in order…methinks.

PS. Capital now hates people more than ever, they get sick and don’t die like they used too, and its told it must look after them…WTF! Better to move back in time, some dark corner of the planet, yet still throw the attack dogs a few bones now and then…they might be needed still.

If Will Rogers said it, it’s because he was quoting Josh Billings.

“This is why fiscal stimulus is vastly more effective than monetary policy at times like these: it has a direct impact on overall conditions, by stimulating demand. Government spending creates more income for businesses and ultimately, consumers. Everyone’s income is ultimately someone else’s spending. If government increase spending, it will increase the incomes of at least some people in the economy, and the improvement in their fortunes (if they believe the new income level will be sustained) will lead them to spend more, improving the affairs of yet more people.”

AGAIN. typical keynesian mistake….”if government increases spending” if I walk into a supermarket without any money…how much can i buy. EVERY dollar spent by the government is a dollar not spent by someone else….AGAIN…idiotic keynesians always making the same mistake….the multiplier is zero…always has been always will be

That is absurd. Your logic only makes sense if there is a supply shortage. In the case where there is plenty of supply of, say, unemployed workers, the government’s spending of a dollar to employ one person doesn’t stop anyone else from hiring some other unemployed worker.

If you are saying the government has to take the dollar from you in order to purchase (not true, by the way), then you could be correct, but this only matters if you want to purchase and the government’s taking of your dollar stops you from making the purchase that you desire (you don’t have plenty of other money with which to make the purchase).

Has anyone noticed that the price of lawyers has not been dropping, despite massive oversupply? Makes a fellow wonder.