As I mentioned in a Labor Day post, I grew up in an America where manufacturing was still the backbone of the economy. I may be more aware of that than most in my age group by virtue of spending much of my childhood in small towns where the local paper mill was the biggest employer. Similarly, when I went to business school, many of my classmates had worked for major manufacturing firms, and the ones who had been in finance (for the most part, two year credit officer programs at major banks) weren’t seen as having better backgrounds than their classmates.

While as other economies developed, the US share of global production was bound to decline, I’m disturbed by the assumption that labor costs are the sole determinant of success. My contacts is that it is an article of faith in Washington is that the US can be competitive only in finance (and presumably in commodities businesses like agriculture). This story line is terribly convenient, since it gives diseased, greedy, and incompetent American managers and policymakers a free pass.

The reason that the attitudes of policymakers matter is that, contrary to popular belief, we do not live in a mythical world of “free trade” but one of managed trade. Other advanced economies have either a formal or informal trade/economic strategy and seem to do better with it than we do? Australia, for instance, has had one of the best growth stories in the new millennium, and that was true even before it got an extra boost from the commodities boom. It also has a more clearly articulated competitive priorities than the US does. For instance, Australia’s Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation funds applied research in ten areas, such as Climate Adaptation, Energy, Preventative Health, and Sustainable Agriculture. It’s hard to say definitively how much of a difference these efforts make, but I’d hazard that they are meaningful. Australia’s position in global wine production has been won on its wine technology, where it is a world leader, and not its terrior.

Another example comes today in a story in the New York Times by Louis Uchitelle “Is Manufacturing Falling Off the Radar?” I have to say, it’s late to be asking this question. The story is framed around the Veneer Corporation, a company that makes industrial machinery. Verneer would prefer to manufacture in the US, but its owners have had to move some of their production to China. The reason? Not cheaper labor, but government subsidies (and formal or informal local content requirements):

Vermeer earns nearly one-third of its annual revenue from exports — counting on the United States government for trade agreements, favorable currency arrangements and even white-knuckle diplomacy to make exports happen. In China, that wasn’t enough. For several years, it had been running into competition from Chinese manufacturers of horizontal drills, supported by their government in the form of free land, tax breaks, cheap credit and other subsidies. With its share of the market falling precipitously, Vermeer in 2008 opened a plant in Beijing, taking a Chinese partner and drawing help for the venture from the Chinese…

A tipping point may already have been reached. Manufacturing’s contribution to gross domestic product — roughly equivalent to national income — has declined to just 11.7 percent last year from as much as 28 percent in the 1950s…

It isn’t that fewer autos or plastics or steel products or electronics are coming out of American factories… But other sectors of the economy have grown faster in recent decades, and that dynamic has reduced manufacturing’s share.

In particular, the finance, insurance and real estate sectors — driven especially by investment banking and home sales — rose from less than 12 percent of G.D.P. in the mid-1950s to more than 20 percent before the onset of the financial crisis, and even now remain nearly that high. In China, in sharp contrast, manufacturing’s share of national output is more than 25 percent. While the United States has a far larger economy — $14 trillion in G.D.P. versus China’s $6 trillion — it has less factory production…

One reason may be that the nation’s political leaders don’t see manufacturing as a problem. Put another way, they don’t necessarily regard making an engine, a computer or even a pair of scissors as having as much value as investment banking or retailing or a useful Web site.

“You have a culture within the elites of both political parties that says manufacturing does not matter, and industrial policy will do more harm than good,” says Ronil Hira, an assistant professor of public policy at the Rochester Institute of Technology.

Why do those at the top of the food chain not like manufacturing? Let us count the reasons. It’s physical. Plants are located where land is cheap. That usually means in the boonies. Powerful people do not hang out in the boonies. Production facilities are noisy, and often dirty and dangerous (my father knew people who were killed or had limbs ripped off in paper mills). Most of the employees are blue collar workers, while to get in the door at McKinsey, you had to be smart and well educated (even the secretarial jobs required high caliber types).

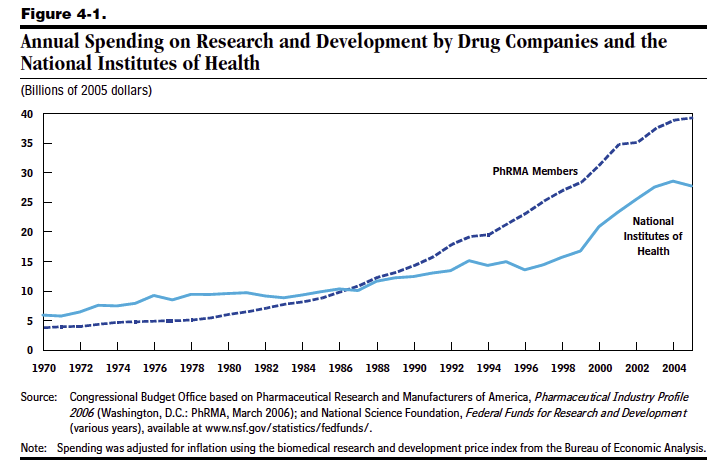

Some readers may react viscerally to the idea of having what amounts to industrial policy. Wake up and smell the coffee, we have it now, by default. As we have discussed, the financial services industry is so heavily subsidized as to not be credibly called private enterprise, save for its governance and compensation structures. Arms merchants benefit not only from government funded research and development, but also from the very long product lives assured by government contracts. Look at the subsidies big Pharma enjoys (and consider: the NIH is the biggest but far from the only source of government R&D dollars. The other big players are National Science Foundation, the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Veterans Administration, and other units in the Departments of Energy, Commerce, Defense, and Health and Human Services). While the chart is a tad dated, the basic picture has not changed since then:

The US has hesitated to push back within the WTO framework. It filed cases against China in certain areas (such as tires) only to have China file tit for tat cases against the US (such as poultry). There was a careful effort to keep the dollar amounts at issue in rough correspondence. The Department of Commerce at first seemed interested in, then declined to file cases against Chinese and Indonesian coated paper manufacturers (the particulars were different in each country, but the program was the same: large scale subsidies). Before Commerce made its decision, some source speculated that Obama would turn his back on the unions who were backing this suit rather than ruffle Wen Jiabao, who he was due to see at an upcoming G20 meeting.

There are no easy solutions to over 20 years of abandoning manufacturing to pursue a “knowledge economy” when there was no reason to treat this as an either/or decision. But misdiagnosis, via blaming the foot soldiers for the failings of the generals, is certain to keep the US from coming up with better courses of action.

A more cultural than economics or political explanation of turning the back on manufacturing can be helpful. Starting with Reagan, the country shifted from a fact based to a mystical/magical based behavior. Starting with Reagan we started to believe in make belief. Make belief and manufacturing are contradictory. While Reagan is the father of the modern deficit, he has been held as a major success almost from right to center left. It is not a big surprise that the “success” of the financial sector is mostly smoke and mirrors; it’s a simple magic act.

Manufacturing was always, in the US and Europe, the stronghold of unions. Reagan started by firing the striking air traffic controls (and therefore their union). A long tradition of official violence against unions has mellowed out only by lowering the physical violence. The political violence against unions has continued from the 19th century through the Obama administration. This animosity has its impact on weakening the standing of manufacturing.

With a temporary break for the Internet revolution during Clinton’s terms, Bush continued in the Reagan pretend magic with skipping a beat. He increased the deficit substantially, strengthened the financial section and continued the war on unions.

Sadly, Obama seems as a seamless continuation of Bush.

Obama is not only pushing bad free trade agreements with Korea, Colombia, and Panama, but he has also been talking up about further free trade agreements all around the Pacific Rim.

This doesn’t make sense in terms of really any rational US industrial policy. In January 2001, there were 17.114 million manufacturing jobs in the US by last month this was down to 11.757 million, a 32% decline in just over ten and a half years.

There are many problems with this. Manufacturing tended to provide high paying jobs with good benefits to those without a college education. New jobs tend to be not as good. It is difficult to get these jobs back. The skills that made industries work are lost or get rusty or technology makes them obsolete.

In this country, both industrial and trade policy are determined by ideology. A lot of this has to do with kleptocracy. Everything is treated as if it is financializable. Societal good doesn’t even make it to the table. It’s all about forcing industry to put a higher priority on its financials than actual real world business concerns even when doing so undermines the company’s long term viability.

Moving industry to China often doesn’t make sense on a straight economic level, but as a vehicle to loot a company by moving its assets outside the US and US control it’s great.

The shorter version of all this is that outsourcing serves the interests of our kleptocratic rentier class. That it harms many and weakens the country, they could care less.

Ah a glimmer of reason –

Wges rates (hourly wages – dollars per hour) are often used as a basis of comparison between the US and some offshore location. So an often repeated remark is “They pay $ 0.10 per hour in India” which while a factual statement it is off the mark.

The real question is what are labot costs per unit of production. And this means labor cost per unit of comparable quality. So what is the labor cost for a ton of steel or a bushel of wheat and so on ?

Simply comparing hourly rates is at best misleading.

I suspect that the offshoring of manufacturing is at least in part a system of allowing China to “buy” US industries through the purchase of US Treasury notes. Note that whole industries have been shipped to China esp textiles and furniture.

Are we really to believe that an entire industry is non competitive ?

Ha ha, the irony, the economic case for outsourcing is based on the Labor Theory of Value!

Offshoring, sorry.

I like to address two aspects in regard to this article.

1. The technology is now mainly located in China in form of manufacturing plants. When ignoring financial aspects, we have a situation that allows e.g. China to simply steal the technology from the big firms in case of a crash of some sort. The large corporations have sold out the technological base of the western countries for short term and personal gains at a much too low price.

2. Historically, a financial crisis is often followed by currency wars, which are presently raging already. After that trade wars are likely to errupt. On that basis, we will have to look for signs of that aspect to show up. It will be a disaster for world trade and especially the earnings potential of large corporations.

Well, it’s not like I don’t understand wars over IP, but why do you say that using someone else’s technology is “stealing”? There’s an implicit assumption in there that the technology was “property” in the first place. Why am I, or anyone else, compelled to agree with your assumptions about “property” rights in technology? Is there some kind of universal morality about technology that I’m not privy to (or too stupid to understand)?

This is what happens all the time. I hear this anger and concomitant proselytizing about something or another; yet I immediately see the assumptions in the argument that are not universally held. What’s the deal with that? Maybe we can all just ratchet down the rhetoric and accept some humility that our perspective on the world is not shared by all. I mean, that’s really the case, isn’t it? I mean seriously?

Listen, I get that you want yours, and you want to get more than someone else. Nothing wrong with that at all. We’re all selfish and want to f*ck everyone else without thinking, and assuming the guilt associated with the fact, that we’re f*cking anyone else. But to ascribe some completely absent morality to it? Gimme a break. It’s embarrassing.

Hey, do not rip off my head. I am simply stating my opinion and I think it is common knowledge that know-how has been transferred on a massive scale and in my opinion at a much too low price. If you think differently, that is ok with me. Maybe you are one of those who made a great deal in getting a nice supply contract for machinery to China not realizing that once they got that technology, they will compete against you.

In addition, once trade wars and similar actions should start, do you think that the Chinese government will really ensure that all those plants stay in the hands of Western Companies? Maybe they will acquire them for a few pennies on the dollar, at least that is what I would do in their shoes.

In addition, I am not angy but I have follow these developments since 20 years and was surprised at how gullible western companies are in this regard. They only think in terms of short term profits and have no long term perspective.

Anonymous Jones,

Forget the emotionally loaded and inaccurate word “stealing”. Even downplay “intellectual property”, which is an intellectually lazy and misleading term (here the correct term is patents). The bottom line is that “American” MNC’s have been transferring American know-how and technology to China and elsewhere at a breathtaking rate.

A classic example is GE’s joint venture to make jet engines in China. Even with royalty free use of all possible patents, making jet engines takes decades of accumulated know-how. There are only three companies in the world making large commercial jet engines worth talking about: GE, Pratt-Whitney and Rolls-Royce. And now GE is busy transferring that know-how to our economic competitor.

You could argue that that know-how doesn’t belong to America. But how did GE get it? What about American support of aviation R&D and production? What about our educational system and numerous other supports for the development of that technology? Is it an accident that it was done here?

And does GE, an abstract entity that exists only by virtue of the US general laws of incorporation (a practical but strange perversion of the “free market”) have any more right to transfer this know-how out of the US than the US has to try and prevent it? Do you think we should slit our own throats economically because of abstract arguments about the meaning of the word “property”?

“You could argue that that know-how doesn’t belong to America. But how did GE get it? What about American support of aviation R&D and production? What about our educational system and numerous other supports for the development of that technology? Is it an accident that it was done here?”

Well, jet engines were invented in Britain and Germany. So how did America get that know-how?

“how did America get that know-how?”

Mostly it was developed here over the last 60-70 years.

You’re confusing the original invention with the later development that lead to what we have today. A modern jet engine has as much in common with a WWII jet engine as a laptop has in common with a vacuum tube computer.

Our first jet engines were developed (under license) as a result of wartime technology sharing (just as British physicists worked on the Manhattan project). But even then it wasn’t a one way street. The US had superior high temperature alloy technology, which was key to improving jet engines.

Since the technology sharing largely ended after WWII, the US and the UK have continued under parallel and competitive engine development, which explains why the only manufacturers worth mentioning are still in the US and the UK.

Someone please help on the research with this but I am certain that the reason the US started moving factory sites overseas in the first place was to cause the Pacific rim to have strong economic ties to the US -we supply the tech know how and start up management (granted, that last one is of questionable value but something is better than nothing on this) and they supply the land, willing cheap labor and easy regulatory environment. I know that is a gloss but I’m sure the Truman and Eisenhower admins were big on this in the late 1940’s and 50s and the only one real reason was for military security more than anything else. The situation snowballed into our total reliance on these countries for many vital machine parts and factory equipment-none of the factory equipment (those highly automated chip makers) that Silicon Valley uses is made in this country.

During the Cold War, especially in the 50s and early 60s, there was a big emphasis on rebuilding industry in Japan and Germany, secondarily Italy, to reduce the appeal of communist political parties by rebuilding the standard of living. Marshall Plan financing tied them to the US economy (the big reason Russia wouldn’t participate in the plan). Something similar was done with Taiwan after the Nationalists fled there in 1949.

AFAIK, not so much of this was done by planting US-owned factories there. Some major corporations did set up operations in these places– IBM, because computers were a new line of industry that hadn’t existed in these places earlier– but the more usual pattern was cross- and part-ownership. So, for example, Chrysler had a piece of Simca and Mitsubishi Motors, as I recall. Capital restrictions had a part to play in this, as did the desire of these countries’ leaders to invite dollars in as reserve currency but to keep the amounts under control so as to avoid excess inflation. This was while Bretton Woods was in effect.

By 1968 the French and other Europeans were changing the game, moving to reduce the growing importance of American retail and cultural influence. This is the real energy that transformed the Coal & Steel Community/EEC into the European Union.

The pressure to offshore US manufacturing came later. It followed a long period of moving manufacturing first to non-union states and then to Mexican maquiladora zones and then into Mexico; this was during the high-inflation 70s and into the 80s. I know less about China specifically, but I do remember a big to-do about super-secret submarine propellers being made in a US defense contractor’s Chinese plant and I believe that was in Bush I’s term.

It’s entirely possible, even likely, that since the “normalization” of relations with China there was a big push by US manufacturers to locate there, not for labor cost reasons but for access to the Chinese internal market.

In fact, thinking out loud, I’m sure of that now. The deal was that in order to sell in China they had to make it there, and the terms were very stringent, something like majority Chinese ownership and all relevant production technology to be installed there. It’s hard to overstate just what a lure it was to these outfits to dangle a billion customers at them. This lure goes way back in American business history, btw.

There’s undoubtedly a story to be told about the role of this technology transfer in creating the Chinese export behemoth, both in setting up productive machinery/experience and in financing the whole development. Probably someone has done it and I just don’t know about it.

I’ve never entirely believed the labor cost argument by itself. It matters, but other things are at work too, like control of the production floor, ability to strong-arm suppliers, etc.

Mostly what’s been going on up to now, I think, has been arbitraging the difference between old prices people are accustomed to, based on domestic US costs and old techniques, and production costs using Chinese labor scale and also vastly more productive new equipment and techniques that really reduce unit costs. It’s just that the investment is made there rather than here, and it’s easier to point to lower labor costs there than it is to talk about what the new capital equipment can do. It certainly serves the interests of corporations more to focus on labor cost than on investment, because we can always ask them why they’re not installing that machinery here.

“The bottom line is that “American” MNC’s have been transferring American know-how and technology to China and elsewhere at a breathtaking rate.”

Or making it available to be stolen, i.e. Fellowes.

http://www.theepochtimes.com/n2/china/american-stationary-giant-brought-to-its-knees-in-china-54204.html

Stealing is the wrong word. Blackmail is closer. (You want to sell into my market, give my companies your technical know-how). But it is only blackmail if you assume a law is being broken.

Industrial policy is the best word because it is accurate and not pejorative.

The situation w/re manufacturing in the US is nothing that a lower dollar and a good industrial policy couldn’t fix rapidly.

People say those skills are gone, the jobs can’t come back. But stop and think, those skills went to countries that tended rice paddies and corn fields by hand. Why would the US have trouble picking them back up?

And to the degree TSMC, Foxcon or Tata know tricks we don’t we can blackmail better than anyone because in most things we still have the largest market.

Where there is a will, there is a way. I will vote for the person who has a will.

Makes no difference if it’s stolen or used under license. The equalizer, from one country to another, was tariffs. But you can’t say that word.

Tessar lenses (cemented triplets) were developed by Zeiss in Germany a century ago and, immediately, were widely copied. By the Americans, by the French, by the Japanese, as well as by all the other Germans (Rollei, anyone?). All of whom had their own thriving camera manufacturers. All of whom made excellent products. Both photography, as well as electronics, have traditionally leapfrogged from country to country. Up to the start of gray importing 30-some years ago, this was never a problem.

Countries that cannot afford to sell their own products to their own people, countries who look to overseas markets to keep their economies afloat, are thieving bullies and parasites.

When the world is divided between bullies and their victims, when the bullies fight among themselves, the result is be war.

David: But it is only blackmail if you assume a law is being broken.

No, the definition of blackmail doesn’t require that it be illegal. It’s a good, and intentionally non-neutral, word to use. Other than that pedantic point I heartily agree with everything you wrote.

Possession is 9/10 of the law. By “stealing” I think he means cleverly getting from us something they probably wouldn’t voluntarily share with us themselves, and who would blame them? By this viewpoint, again, they are behaving cleverly while we might be said to be behaving naively or shortsightedly.

It didn’t help that economists like Paul Krugman provided massive economic cover for the gutting of our manufacturing sector. I remember reading a pathetic mid-90s essay from Krugman comparing manufacturing to selling hot dogs. It was shallow and thoughtless analysis, yet he and the aptly named Alan Blinder made careers on this type of crap analysis to the detriment of the country. With Yves and other influential people (Intel ceo Andy Grove et al.) continually beating the drum, not to mention the nascent DIY open-source hardware movement exploding from the ground up and leading to ingenious devices like 3-d printers, complex sensor systems, robotics, etc., I am fearful and yet excited about the future of manufacturing in the US. The Washington consensus will be broken if we keep it up. It would also be nice if Krugman could begin to admit his errors and not just where he has been correct.

I’m guessing this is the Krugman hot-dog article, from 1997:

http://www.slate.com/id/1916/pagenum/all/

Now that’s the real Thugman, the one his sycophants today lie out of existence, or are ignorant of in the first place. (For many “progressives”, being typically ignorant of history, history begins with K’s pretending to oppose the Iraq war, when as we know today he only opposed Bush’s war.)

The fact, however, is that the U.S. economy has added 45 million jobs over the past 25 years–far more jobs have been added in the service sector than have been lost in manufacturing.

That was Krugman’s core agenda: Sole proprietors and middle class manufacturing jobs should be destroyed but replaced by a greater number of minimum wage Walmart greeter “jobs”.

The public system should be burdened and everyone’s quality of life should plummet, and democracy and local economic control should be obliterated, so that Krugman’s Walmartization wet dream could become the universal nightmare.

Notice how he hasn’t found himself yet as a propagandist. He starts out with a clumsy attempt at informality in his tone, but by the end his supercilious elitism is reeking from the page:

Needless to say, I have little hope that the general public, or even most intellectuals, will realize what a thoroughly silly book Greider has written.

Meanwhile, he never gets around to answering the question I had immediately: If productivity has gone up so much, why can’t everyone work that much less?

We know the true answer, of course, but I’d like to hear whatever lie he’d try to spew in place of it.

I hadn’t seen this one before. In return, here’s my favorite, “In Praise of Low Wages”.

http://www.slate.com/id/1918

Oh I hadn’t read that last Krugman gem. Its great how he cares so much for third world peoples. His moral courage is so bold from his perch at Eden-on-the-Atlantic. So wage arbitrage leading to the plummeting standard of living, massive increase in hunger and food stamp use in the US, and slave labor in Bangladesh is a good thing for the world. Isn’t it just darling how much the average Bangladeshi worker has climbed the ladder of capitalism over the past 15 years since Krugman so decisively and morally penned his classic globalization ouvre?

Yes anon, that is the one. Its so laughable, flippant and un-prescient, I bet Krugman would love it to just disappear altogether. Thanks to Slate for keeping it posted for all the world to see what a flack and quack Krugman truly was, ya know, before his Nobel and all that. And the subject of the article (for it pretends to be a book review of sorts), William Grieder, looks better than ever. How’s Krugman’s “conscience of a liberal” doing now I wonder? If he would just repudiate his terrible work from that period, and while he’s at it his blindness on commodity speculation and foolish jabs at MMT, I could actually begin to respect him a little.

Thank you for that! Krugman looks like an idiot, Greider like a prophet. Those Nobel folks need to reassess …. LOL

This is completely meaningless rhetoric coming from you lot. I see no real refutation of Krugman’s main argument, which I found to be both useful and readable.

OK, since your Leader was too much of a coward to answer it, you answer it:

If productivity has gone up so much, why can’t everyone work that much less?

I think the point the above posters are trying to make they find so self-evident it would be patronizing to re-state it. But I will: Service sector jobs paying a few dollars an hour above minimum wage are hardly comparable to a skilled union-wage manufacturing job paying far more.

That hot-dog article was really hideous. It reminds me of CPI metric changes in the early 1990s:

“The Boskin/Greenspan argument was that when steak got too expensive, the consumer would substitute hamburger for the steak, and that the inflation measure should reflect the costs tied to buying hamburger versus steak, instead of steak versus steak. Of course, replacing hamburger for steak in the calculations would reduce the inflation rate, but it represented the rate of inflation in terms of maintaining a declining standard of living. Cost of living was being replaced by the cost of survival. The old system told you how much you had to increase your income in order to keep buying steak. The new system promised you hamburger, and then dog food, perhaps, after that.”

http://www.shadowstats.com/article/consumer_price_index

I’m going to assume you are referring to the “hotdogs” article Cahal, so here goes:

Right off the bat, when he begins his stupid hot dogs and buns analogy, he states: “(Hey, realism is not the point here.) ” I know what he’s trying to say, but it begs a question: how can such a simplistic scenario possibly capture the complexity of an entire economic system. More on this later…

His first real doozy is this one:

“Meanwhile, economists are a bit bemused, because they can’t quite understand his point. Yes, technological change has led to a shift in the industrial structure of employment. But there has been no net job loss; and there is no reason to expect such a loss in the future. After all, suppose that productivity were to double in buns as well as hot dogs. Why couldn’t the economy simply take advantage of that higher productivity to raise consumption to 60 million hot dogs with buns, employing 60 million workers in each sector?… In our hypothetical economy it is–or should be–obvious that reducing the number of workers it takes to make a hot dog reduces the number of jobs in the hot-dog sector but creates an equal number in the bun sector, and vice versa.”

As an avowed Keynesian (albeit a shallow and flawed one) Krugman should know that DEMAND is not so elastic, and over-production is a plausible scenario. His supercilious tone notwithstanding, the idea that productivity increases never lead to a net loss of jobs is preposterous on its face, never mind what happens when robots take over jobs.

Lets move on.

“But wait–what entitles me to assume that consumer demand will rise enough to absorb all the additional production? One good answer is: Why not?”

Great answer. I’ve got a better answer: Why?

And here is the triumphant finale of boob-dom:

“Greider would answer: that while I am talking mere theory, his argument is based on the evidence. The fact, however, is that the U.S. economy has added 45 million jobs over the past 25 years–far more jobs have been added in the service sector than have been lost in manufacturing. Greider’s view, if I understand it, is that this is just a reprieve–that any day now, the whole economy will start looking like the steel industry. But this is a purely theoretical prediction.”

So who was right? It’s not theoretical that if you replace manufacturing of valuable high-demand goods with a service economy that produces foolishness and waste (things we can certainly do without, very easily), when things turn south the jobs producing something of true value that require skill and complex organization will be more resilient and less likely to be lost… and higher paying as well. People need cars, computers, televisions, dishwashers, bicycles, kitchen tools and utensils etc. They DO NOT NEED food cooked for them in restaurants, salons, spas, public relations douchery, advertising and other assorted luxuries of the much-vaunted service economy. So Cahal, please tell me what in this “essay” of Krugman’s you find so enlightening? I’m actually curious to know…

attempter,

He is not my leader you absolute cretin. I am incredibly critical of his neoclassical stance. Can you stop acting like a crazy asshole for 3 seconds? Cheers.

People could work for fewer hours but it wouldn’t detract from his point, which is that productivity gains needn’t lead to job losses.

Steph,

‘But I will: Service sector jobs paying a few dollars an hour above minimum wage are hardly comparable to a skilled union-wage manufacturing job paying far more.’

Aren’t you implicitly assuaging all service sector jobs are as bad as McDonalds? I’m pretty sure most people prefer working in an office to a factory. Also the fact that there are no unions is a practical problem and has little to do with his analogy.

Yankee,

‘Right off the bat, when he begins his stupid hot dogs and buns analogy, he states: “(Hey, realism is not the point here.) ” I know what he’s trying to say, but it begs a question: how can such a simplistic scenario possibly capture the complexity of an entire economic system. More on this later…’

Albert Einstein used simplistic thought experiments. They aren’t automatically useful but simplicity can help us tease out some information; in this case Krugman shows how intertwined economies are and why productivity gains don’t necessarily increase unemployment. I found it useful.

‘His first real doozy is this one:

…

As an avowed Keynesian (albeit a shallow and flawed one) Krugman should know that DEMAND is not so elastic, and over-production is a plausible scenario. His supercilious tone notwithstanding, the idea that productivity increases never lead to a net loss of jobs is preposterous on its face,’

I’m not the Krugman defence league though so I will agree with you that he can approach things from an overly aggregated, homogenised perspective. But you are expecting too much from a hot dog story – he has stated it is overly simplistic and is using it to demonstrate a single, maybe two points.

‘never mind what happens when robots take over jobs.’

People are also employed to build, design and maintain the robots?

‘Great answer. I’ve got a better answer: Why?’

I could come up with some psychological crap about how humans always demand stuff but it is clear this is what happens in the real world. Consumption rises with income – it has throughout history. You might say this isn’t desirable but that wasn’t Krugman’s point.

‘So who was right? It’s not theoretical that if you replace manufacturing of valuable high-demand goods with a service economy that produces foolishness and waste (things we can certainly do without, very easily), when things turn south the jobs producing something of true value that require skill and complex organization will be more resilient and less likely to be lost… and higher paying as well. People need cars, computers, televisions, dishwashers, bicycles, kitchen tools and utensils etc. They DO NOT NEED food cooked for them in restaurants, salons, spas, public relations douchery, advertising and other assorted luxuries of the much-vaunted service economy.’

You seem to be missing the point of his essay. These are all valid questions but he is simply making a point about productivity gains and unemployment.

‘So Cahal, please tell me what in this “essay” of Krugman’s you find so enlightening? I’m actually curious to know…’

Please don’t project. I found it enjoyable because it demonstrates how intertwined different industries are. I didn’t expect it to tell me everything I need to know about the economy.

It’s this exasperated language:

This is completely meaningless rhetoric coming from you lot.

which indicates you’re not just joining an argument but annoyed that an idol of yours is under attack. On the merits, how could anyone’s “rhetoric” be more meaningless than the stupid hot dog analogy (which I see cited all the time, BTW, pin factory move over!). Your Krugman himself admits it’s stupid.

Aren’t you implicitly assuaging all service sector jobs are as bad as McDonalds?

I’m not sure what language that is, but yes, most of them were lousy to start with and have only gotten worse.

I’m pretty sure most people prefer working in an office to a factory.

I bet, if it means getting paid better for not having to do any actual work. But what’s that I hear, after they came for the factory jobs and you didn’t care because you were superior Galtian “office workers” (the paltriness of Randianism always amuses me; I idolize maitre d’s myself), now they’re liquidating white collar “workers” as well? Hmm, that didn’t work out so well, did it? (Thugman, of course, always knew that would happen.)

BTW, what’s intrinsically bad about factory work? Everything that’s ever been really bad about it was not inherent to it, but was the purely artificial and gratuitous result of capitalism. So you and your fellow doomed “service economy” refugees were merely indulging in escapism and collaboration. You didn’t care about the crimes, indeed as we see here you supported them, as long as you personally were exempt from the worst treatment and could be one of the relatively coddled flunkeys.

But now they’re not coddling you any more.

I could come up with some psychological crap about how humans always demand stuff but it is clear this is what happens in the real world. Consumption rises with income – it has throughout history.

Yes, and will rise infinitely…”Psychological crap” indeed. One would have to be an economist (or a sycophantic worshipper of them) to believe such idiocy.

Of course, you’re empirically wrong already. Through the vast majority of history consumption was pretty stable. Like all other forms of “growth”, growth here was purely the result of the fossil fuel binge. In the end it will have been as ephemeral as the binge itself was.

You never engage the fundamental evil of 90s-era propagandizing for globalization’s coming home to the West even after one’s having seen it in action around the unindustrialized world in the 80s. Any non-evil writer would have warned against it and called for an end to the assault on the global South as well. Krugman, a vicious little thug at his core, of course continued cheering it on, and wanted to see its total triumph. That was the #1 goal of his career.

And you didn’t answer my question, just like I knew you couldn’t. The implication of it was clear: Given such productivity gains out of technology and organization, why would anyone call for anything other than permanent full employment at a living wage and at far fewer hours than we now work? Clearly the productivity would easily afford it. So why did not e.g. Paul Krugman call for that, instead of calling for lower wages and the continuation of the “job” model itself?

We know the answer, and your refusal to give a real answer proves you know it too. Your line about your office elitism also provides some insight.

Jesus I started to reply to you para by para but when I saw the comparison to Ayn Rand and some weird suggestion that I was an ‘office elitist’ I gave up.

I did answer your question: I said we could also work fewer hours. But Krugman didn’t mention that because that wasn’t what he was trying to demonstrate. I expect if you asked him about a reduction in the working week he would support it.

You can try and read as much illuminati into Krugman’s work as you want, or you could realise that it was just an accessible thought experiment for a pop magazine that demonstrated a single point, and did it well.

Priceless! We need more verification of predictions of the future by famous economists. Give them a decade or two and it is pretty much guaranteed that most their predictions will look silly.

Anyone who consumes economic predictions, especially if they pay for them, should require the author to submit a list of their past predictions with independent analysis of their agreement with reality.

CSIRO is bad example, CSIRO is fucking patent troll, they are extracting rent out of american corporations!

https://encrypted.google.com/search?q=Australia%E2%80%99s+Commonwealth+Scientific+and+Industrial+Research+Organisation&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-8&aq=t&rls=org.mozilla:en-US:official&client=firefox-a#sclient=psy&hl=en&client=firefox-a&hs=bm2&rls=org.mozilla:en-US%3Aofficial&source=hp&q=+Commonwealth+Scientific+and+Industrial+Research+Organisation+patent+troll&pbx=1&oq=+Commonwealth+Scientific+and+Industrial+Research+Organisation+patent+troll&aq=f&aqi=&aql=1&gs_sm=e&gs_upl=26604l26604l1l27049l1l1l0l0l0l0l288l288l2-1l1l0&bav=on.2,or.r_gc.r_pw.&fp=3e82efc6cc141df0&biw=1146&bih=751

It looks like you know little about CSIRO. It has lots of scientists and engineers in its employ, and as I indicated in the post, can point to tangible accomplishments, such as Australia’s world leading position in viniculture. That was a home-grown success.

They may do things you disapprove of, but that does not represent the bulk of their work.

Without the government enforced/backed counterfeiting cartel, the banking system, to borrow from it is likely that most corporations would be heavily owned by their workers. How else could the corporations have financed themselves except by sharing ownership with their workers?

And if the corporations had been heavily owned by the workers, is it likely that they would have voted for management that outsourced their jobs?

“Banks have done more injury to the religion, morality, tranquility, prosperity, and even wealth of the nation than they can have done or ever will do good.” John Adams

Well said Mr. Beard.

Please. You explained pretty well precisely why there shouldn’t be an “industrial policy”, because it just becomes another budget item with no purpose other than maximizing management payouts. Also see: Solyandra.

Textiles left decades ago. Has nothing to do with “subsidies”. It was pure labor arbitrage. There may be examples of subsidies shifting some manufacturing on the margin, but it isn’t the cause.

I just read a story about Foxconn. They pay their workers $130/month. I gather there are minimal benefits. The workers run 12 hour shifts.

I doubt Foxconn is an isolated example, but maybe it is. I just don’t see how industrial policy competes with that.

Sorry –

I beg to differ.

Textiles did leave decades ago as did furniture.

However labor costs (depending on process) usually ran at about 10 – 15 % and with the advent of machine level microprocessors and other capital improvements the labor costs were expected to drop to 7 – 10%. CNC machinery for example has seen a significant impact on labor in machining and metals fabrication.

The major portion of costs in textiles manufacture were raw materials at about 60%.

Since most manufacturing concerns engage in a relatively simple money laundering scheme called givebacks this is where real improvements could be made but never were – it paid the companies too well.

Note that the present US financial / tax structure encourages givebacks – these are very common in the automotive manufaacturing operations. Paper operations for example are well known for purchasing pulp are inflated giveback prices. Automotive interior manufacturers often purchase plastic resin for injection molding at price 2X the market for the expressed purpose of attaining a giveback. These schemes increase the cost of goods to the consumer without any benefit other than a fungible stream of cash to mnangement.

And for those who continue to assume that labor costs are the driving force one should ask – Why are companies like Nissan, BMW, Honda, and so on building plants in the US ? After all if labor costs are the driving force these plants must be noncompetitive particularly when labor intensive assembly plants have a relatively large labor cost.

And if labor costs are lower from offshore operations why don’t we see lower prices in retail ? We all should benefit from lower costs – our standard of living should be much improved right ?

Your comment is remarkably devoid of facts. Direct factory labor costs do not determine final product costs. I discussed that in the earlier post I linked to. Direct factory labor is 11-15% of product costs of most manufactured goods. Supervisors and management overheads, shipping costs and financing are considerable offsets. I’ve had staff at companies that offshored their manufacturing say their internal analysis said it wasn’t justified, but Wall Street was pressuring them for it

So what you have going on in some if not many cases is that the managers are simply increasing their pay by making their jobs seem more complicated on the backs of factory labor. Offhoring is a transfer, not a cost saver.

One example is the popularity of outsourcing call centers to India. Gee, this is an isolated function that is pure labor. You’d think you’d see very clear cost savings. Wrong, Garner found that outsourced customer service operations can cost almost a third more than those retained in-house, according to a new study by Gartner. This was in 2005 and the dollar has weakened since then, so the economics can’t have gotten better:

http://news.cnet.com/Gartner-Outsourcing-costs-more-than-in-house/2100-1022_3-5600485.html#ixzz1XeNnUBs7

This 2011 article discusses that IT outsourcers aren’t offering a labor cost advantage, nor do they seem able to work “smarter”, as in deliver cheaper total costs even with no labor cost savings:

http://www.sourcingspeak.com/2011/04/when-less-expensive-is-not-cheaper.html

This is best seen in a number of very recent proposed IT outsourcing transactions where the supplier’s unit price is not much less (or not lower at all) than the internal customer’s cost to deliver a comparable service. But, even in these cases, customer IT management, as well as a customer’s business management, still view the total cost of providing IT services as much too high. How can this be? How is it that a customer’s unit cost to deliver a service is not much greater than the outsourcer’s price to provide the comparable service, but all users of the IT service still view the cost of the service as too high?

Total price has always been a function of price times quantity; what the industry often calls “P x Q.” If the unit price component of the customer and outsource supplier are comparable, then the only culprit for too high a cost must be the quantity of widgets being used to deliver the service. And this, in fact, is what we are seeing on an increasing number of recent proposed IT outsourcing transactions. It is not that the customer’s unit costs are too high, but rather that the customer is using too many resources (widgets) to deliver the service. The implications of this for the outsourcing market are straight-forward but profound: suppliers need to start competing not only on unit price but also on their abilities to deliver the service with less resources than those used by the customer.

Unfortunately, suppliers have in many cases either been unwilling or unable to rise to the challenge and offer solutions focused on a reduced quantity of resources and not merely a lower unit price.

So, to translate: American management assumes foreign labor = lower costs, but they find the ADVERTISED rates of outsources are not cheaper than their internal costs. So that means if they want to save money, they need to figure out a way to be more efficient. But rather than do that, they instead dump that request on the outsourcer, who isn’t in any better position than they are to do that and can’t deliver.

This proves my point about diseased, greedy, and lazy American management. And you are carrying their water.

You’ve cherry picked one example with Apple. How about we look at another big and supposedly savvy player, Boeing? And remember, you have sample bias. Companies are gonna tout their offshoring/outsourcing successes and try to hide their failures.

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/02/boeings-multi-billion-outsourcing-fiasco.html

And you are wrong in your blanket assertion re textiles. I had a Japanese client which was a world leader in spinning technology buy a cotton spinning mill in 1988. I Googled where ht bought the plant, in Gastonia. NC, and found there are 7 yarn spinning mills in Gastonia.

http://www.123searchonline.com/yarn-spinning-mills-4135/NC/gastonia/

That’s way down from when North Carolina was a spinning center, but the fact that mills are still operating disproves your thesis.

As Michael Thomas, a former investment banker and later financial columnist and novelist, remarked via e-mail: “It was at least fifty years ago that my father observed to me, “Most American companies are run for the entertainment of the management.”

I do my part by keeping call centers that I know are offshore on the phone as long as possible. I ask to speak to their manager, interrogate them about how much they are paid and then announce that if they were in the U.S., they would be paid twenty times more and what a shame it is that the products they are shilling for cost a fortune and that they are basically just slaves.

Outsourcing IT was not about cost, it was about dismantling a cartel. The IT silo was consuming more and more company resources without improving productivity. Departments were huge and did not meet the needs of the users. The very last consideration with respect to a software purchase evaluation was usability. IT did not have to use it, they simply maintained it. Those were terrible times.

Oh that’s good — a “cartel”. This reminds me of Colbert’s diatribe against “big deli”. Except Colbert was making a joke to prove a point. What’s your excuse?

Americans over the course of 2 generations have been taught things that are factually false or just lies, and they lack the ability to deal in reality. The rest of the world uses industrial policies. We are alone in this.

There are very good reasons to have an industrial policy, and there are limitations, but often, the limitations aren’t what is being discussed. Its the delusions and/or factually wrong statements by those with an ideological agenda to push.

This crops up everywhere in our society- ideologues claiming that they are speaking economic policy who are actually speaking ideology, and because the assumptions that they spout are held as true, it is hard to combat the arguments they make because one ends up spending a large amount of time just trying to cut through the babble to find out that there is something behind it other than what they should be the case rather than what is actually the case.

“Outsourcing IT was not about cost”

Outsourcing is not necessarily offshoring. Outsourcing IT to a company down the street may make sense, just as it may make sense to hire an outside cleaning service instead of hiring your own janitorial service. But outsourcing per se has _nothing_ to do with shipping the jobs to India.

My experience over the last decade is that the quality of IT support has declined markedly. And it definitely has an effect on productivity as I (and millions like me) waste countless hours because we can’t get decent IT support. But mindless morons who don’t understand “judgment”, and whose “intelligence” is limited to entering Wall Street blessed formulas into spreadsheets, don’t see it that way.

The Gartner article strongly suggests that is is largely if not entirely about cost. I do know more than a bit about IT outsourcing (my brother has spent his entire career in that business, and I know some consutants who have tried to set up a boutique to compete with the major incumbent “consultants” who basically broker the deals and do a fair bit of the deal structuring and negotiation). All my sources confirm that cost savings are a major and in many cases sole driver of these deals. The PR otherwise is likely to prevent more pushback.

Yves: “diseased, greedy, and lazy American management”

Stop pulling your punches. How do you _really_ feel about it.

It would seem you are arguing that the firms’ managers are acting irrationally in terms of cost?

Would you say that’s true?

If so, why is this not more widely understood, and have you tried to with your limited ability to get the message out there?

The only water I am carrying is that of logic. Foxconn, if anything, pays better than market. A few percent of savings here or there adds up for low-margin products.

Labor costs are only one part of the equation of savings of course. Environmental regulation compliance can be avoided for example.

Companies make decisions for lots of reasons, so no doubt you are right that there are examples of offshoring which are non- economic. I think however most of the offshoring is economic, and an industrial policy is not going to be offset that.

In fact, an industrial policy is just going to become another instance of corporate welfare for the politically connected, ie Solyandra. I am sure US corporations and especially their management would LOVE an “industrial policy” So whose water are you carrying, Yves?

“I think however most of the offshoring is economic, and an industrial policy is not going to be offset that.”

Which is why we also need to talk about exchange rate policy (although logically that should be viewed as simply part of industrial policy, as China and most of East Asia does).

“In fact, an industrial policy is just going to become another instance of corporate welfare for the politically connected”

Right. Let me know when the cost of our industrial policy hits 1% of the cost of our FIRE sector policy.

BTW, do you think China is making a mistake with its industrial policy? For example by heavily subsidizing its solar power industry.

“ie Solyandra”

Again with the jokes. See my 2:10 post. Solyandra is chump change compared to what’s done for banks and with what’s at stake.

“I am sure US corporations and especially their management would LOVE an ‘industrial policy'”

Don’t bet on it. Many “American” MNC’s are so vested in foreign manufacturing that they might not be thrilled with the shift.

Well Alex, go on CNBCs website they just posted an article “Rich tax breaks help video game makers”. is that the industrial policy being referred to here? The companies referred to in the article have no complaints.

The CNBC article is a reposting of a NYT article from this morning. Just saw that.

Bruce: “Rich tax breaks help video game makers”. is that the industrial policy being referred to here?

Is that the sum total of your rebuttal? An article on tax breaks for video game companies? (which aren’t even manufacturers). No comment on exchange rate policy, or whether China’s industrial makes sense for them? Ok.

Delving into the article we see “because video game makers straddle the lines between software development, the entertainment industry and online retailing, they can combine tax breaks”, none of which have anything to do with industrial policy.

What else … “as head of tax at Electronic Arts, he became a noted expert in using foreign subsidiaries to legally, and sharply, cut a corporation’s United States tax bill.” Which is exactly the sort of thing that advocates of industrial policy oppose.

Lastly, while I’m not thrilled with the shenanigans described in the article, I’d rather see the video game industry subsidized than finance. At least the video game industry produces something that people find to be of value, and with the possible exception of a few particularly violent or anti-social games that make headlines, I see nothing wrong with that. It’s also an export industry. And while people deride video games, mostly they’re not aware that video games are actually on the bleeding edge of software technology (a bit funny, but absolutely true). And yes, that technology does find its way into other software.

“They pay their workers $130/month. I gather there are minimal benefits. The workers run 12 hour shifts.”

Automated factories will replace these workers that is there future. Exports outside of mineral and ag base products have a limited future. Shipping costs along with automated factories fighting over the same markets will probably kill off what we now call international trade pushing the world wide consumer consumption business towards local and regional

large scale automated manufacturing centers.

Bruce: Solyandra

Oh Lord, not another rant about that. $535M in loan guarantees down the tubes. The taxpayers money!

And what about the billions, nay trillions, in loans, guarantees, and in some case outright gifts to the FIRE sector? Compared to that Solyandra isn’t even a rounding error. And what does the FIRE sector produce? Housing bubbles, financial scams, etc. Compared to such valuable products, how can one even talk about clean energy?

And what about the enormous subsidies, including military protection, given to fossil fuel companies? When do you think BP is going to get the real bill for cleaning up the Gulf?

But Solyandra, yeah, that was a waste of taxpayer money. Imagine, not every venture works out. Oh, and a good part of the reason for Solyandra’s failure is that China subsidizes their solar industry even more heavily.

Alex,

I am simply pointing out that ” industrial policy” is ripe for abuse, eg Solyandra. And I also said that the problem with such a policy is that in our current system, it would be abused just like all the other corporate handouts. So if one is arguing for an industrial policy, one is arguing for corporate handouts, because no matter how good the intentions at some point it will turn into just another income stream for management.

“the problem with such a policy is that in our current system, it would be abused just like all the other corporate handouts”

Unfortunately there’s some truth to that, but the alternative of pretending to have no industrial policy is worse. Other countries have industrial policy and we have to fight back, lest we continue with our hideous trade deficit and serious unemployment problems. I’d rather see the policy favor industry over finance, as industry is capable of making something other than bubbles and scams. It also provides a hell of a lot more decent jobs.

Not one word about automation/software/computer intelligence, its as if its 1937 and the issue is labor vs management or imports and trade killing off our economy. Computer intelligence combined with software applications alone will gut millions of office and management positions in the near future and manufacturing output will continue to become centralized and automated.

Maybe you are right.

I would like to render a note of caution. We do think too much in linear terms. However, history shows that we may suddenly experience what is known in physics a “phase transition” which is a rapid change of a condition. On the basis of the presently rather instabil economic conditions worldwide, I could easily imagine that we arrive at a sudden change of the present system whether derived from political mood change or economic nessecity.

Always those typos, sorry …

Yes the microchip will and is making a huge impact on production costs

However the microchip / computer will not impact labor rates (i.e. dollars per hour). This means that the advantage of the microchip / computer has the potential to be spread equally to lower and high wage rate locations.

Of course we should bear in mind that whole factories were offshored meaning that the obsolete machinery with a lower level of microchip / computer control effectively put the purchaser further behind in the competitive market.

That’s how top management, Wall Street, economists, and policymakers are framing these issues.

Sure technology plays a part in all this – but the Germans have shown that it is part of the key to an industrial policy for their country when combined with societal goals

GATT must be overturned – the reason the politicians put it thru in 1994 – republicans and democrats – were payoffs by corporations. Everyone knew that labor rates in China/Laos / Cambodia were $250 per month with a 6 day week and ten hours a day.

The promotion for passage of the treaty – was exports would substantially increase but their real objective was to get into the USA consumer market with better margins on recognized consumer Brands with foreign labor content and therefore increase their margins for IMPORTS into USA by multi nationals who shed US jobs and higher cost with “free” entry to the market into the largest consumer market in the world. Access given away for free – no corporate income taxes (the transfer prices are all manipulated as well).

The USA population of 310 million does not need 160 million people – either we put them to work or the republicans will murder them by neglect by the elimination of Medicare and SS in the first phase of the great downsizing of American population. The next phase will be more obvious!

The country needs a VAT and Tariffs that – DISCRIMINATE – against imports – essentially two rates – and take the higher cost of US made goods as a cost of maintaining a “balanced” society – like the Germans

Sure there is retaliation but we have that already from

china with currency manipulation and other tools and the exports are not enough to sustain the employment.

There was a – BILLIONAIRE – who said all of this in 1994 – he was a brilliant and thoughtful guy and a corporate raider who understood the margins in this devils trade and the effect on society. Take a hostile deal or bear hug and do an LBO and then pay for it with a good brand shipped overseas for manufacture.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4PQrz8F0dBI&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SZTzPmn-87w&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=A_hiEvTNV5k&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yonUgZ2Y6Qs&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YW6KkF6aa_A&feature=related

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IDxufaKZLjc&feature=related

Thank you for this!

This should be “mandatory” viewing

Goldsmith makes a case that any “reformer” worth his/her salt should be making and he asks and answers THE most important question – “What’s an economy for?” Interesting that we never see that question asked, let alone answered in any “humane” way, anymore …

So maybe you can answer the question I asked above.

If automated productivity and efficiency have improved so much, why can’t we all work less? (Much less, according to the hype.)

Attempter: The answer to your question “If automated productivity and efficiency have improved so much, why can’t we all work less? (Much less, according to the hype.)” You are being rhetorical, right? You have many times stated the answer.

This is what I say: Who benefits from all the “productivity and efficiency”, answer: the corporatists of course. Their greed drives for more, more, more and because they take the fruits of the productivity and efficiencies of others the producers must continue to slave away.

You are being rhetorical, right?

Of course. I just want to see if anyone’s shameless enough to try to give an “answer”.

“If you would ever get into a situation when you didn’t have the trained and skilled folks available to operate the units,” said Bruce Raiff, who oversees “knowledge transfer” programs for Dow’s Texas operations, “you’d have to shut the units down.”

“Companies are not very long-term-oriented,” he added. “They don’t spend much time worrying about what might be coming down the pipe in the future.”

Quotes from: http://www.washingtonpost.com/business/as-workforce-ages-industries-struggle-to-prepare-for-wave-of-retirements/2011/08/29/gIQARlvVwJ_story.html

Manufacturing is hard. It requires planning as there are usually major allocations of capital with little immediate return, it requires a wide variety of technical skills, and it requires real management. all of these are “easier” in the short-term to address using a foreign work force that is more compliant with fewer rules regarding safety and environment to comply with. Even the Chinese are discovering this as they outsource some of their basic manufacturing.

The financialization of the US where something or someone does not have value unless it can occupy a cell in a spreadsheet means that short-term decision-making to maximize quarterly profits will trump all other considerations. We are even seeing it in the service sector on a massive scale as the banks did not staff up to manage their increased paperwork requirements involved with securitizing mortgages. In the manufacturing sector, it has risen to the point where our companies are willing to hand their future competitors technology in order to maximize short-term profits. I don’t think the Germans are doing that on a large scale.

Ironically, a permanent increase in energy costs may be the slavation of US manufacturing and the US middle-class as the cost of trasnporting finished goods sky-rockets around the globe. The massive loss of manufacturing facilities will require construction of new state-of-the-art facilities which could push us ahead in manufacturing. I don’t think that is what Helicopter Ben had in mind with his easy money policies, but it may be one of the only good outcomes.

A hidden and rarely mention cost of offshoring is the loss of intellectual capital – you know that guy on the shop floor. The guy who didn’t go to college but can setup a paper machine quickly and efficiently, the guy who can run a boiler safely and efficiently, the guy who can make turbine blades.

When these jobs are offshored these talents go begging and are often lost forever so that in the end we are forced to rely of faraway talent.

“The guy who didn’t go to college but can setup a paper machine quickly and efficiently, the guy who can run a boiler safely and efficiently, the guy who can make turbine blades.”

But that guy has dirty hands, so he couldn’t possibly have any brains. So sayeth our Wall St. geniuses and various pundits (not to mention too much of the general public).

I think the root cause of the decline of manufacuting is the intense discomfort of the elite towards working class people, ever since FDR and before.

If I may follow up to my own post, it is easy to get an investment in arugably worthless gargage like FACEBOOK, which does not employ squat, and near impossible for a manufacturing company to gain access to finance. The WSJ once ran a story about a furniture manufacturing company in North Carolina, compared to its counterpart in China. The US company was in an old building with operations inefficiently spread over three floors, wheras the Chinese one was in a modern building, with robotics, and fewer workers. Cheap labor was not a factor. Willingness to invest and availability of capital was.

The economics of software are compelling. Is that what you mean? Damn shame about that.

I’m not a fan of Facebook, but you underestimate how easy it is to write great software and host the world on your servers. You try it.

Then try writing great enterprise software and getting it sold and rolling out a new edition. Not so easy as it may seem.

Yves can see the problem of the elites thinking of manufacturing as dirty, boring, and (they think) not really necessary for a major economy like the US. They think “clean” finance and “tech” jobs are the answer. I belive the “service” sector as one the largest players in our economy cannot be sustained. As our economy declines (Grocery stores replaced with asian style markets– pigs and chickens for sale in pens!!?) I have a saying, China-from BICYCLES TO BUICKS, the United States of America— from BUICKS TO BICYCLES.

I enjoyed your comment – as my bicycle has become my mode of transportation while my 18 year old Buick is in the shop having major surgery. Between finding someone who still has the skills and who won’t decide that they know better than i whether it is “worth” fixing, it is has been an informative “adventure” in “economics” …

it is sad that our politicians have sold the middle class down the road. Both parties are to blame. One more “off subject” comment is on regulation. I believe that massive OVER regulation can cripple an economy—I also believe that massive UNDER regulation will have the same effect. A reasonable balance has to be achieved.

Yves, I think the core reasons for the decision by US corporations to divest in the US to fund overseas production are these:

1. Fortune 500 companies, like the one I retired from, decided in the 1980s the US consumer market had a low growth future because of our demographics. Our consumer base would age, its buying power would decline and low birth rates would not shift the balance to younger consumers. The biggest component of our decision to shift oversea was our sense consumer markets outside the US offered far better growth potential.

2. We also realized we could increase profit margins by taking advantage of much cheaper overseas labor. It was much more profitable to manufacture abroad to serve our markets worldwide.

3. The stock market and its options incentives for C class executives forced us to divest in the US as much as possible, to keep corporate earnings and top executive bonuses on the upswing. If we didn’t divest in America, our competitors would and the market would punish us and reward them.

In short, the magnet of tremendous overseas market growth is the primary reason for Corporate America’s decision to reallocate its capital investment from the US to South America and emerging East Asian markets. No government policy can offset this. Add to that the ability to leverage much lower production costs, including labor, regulations and taxes and it is inevitable this divestiture had to occur.

The only way to restore our manufacturing base so we can generate enough jobs to keep up with workforce growth and as importantly to reverse our $10 trillion negative balance of trade, which now grows at $1 to $2 billion every day, is through tariff protection and a Buy American policy for all our governments. The free market will inevitably dictate corporate reallocation of production so it fits best with global consumer market growth as well as global profit margins.

The free market/free trade dogma will continue to hollow out our economy and accelerate our downward spiral to a second rate debtor nation. We must abandon our slavish devotion to a mantra that is consuming us from the inside out.

We must invent and protect a sustainable national economy.

Yes, consumer goods will be more expensive, but at least Americans and not the financial community via the IMF will determine our economic and hence our national destiny. Our primary focus must be restoring our national economy.

The role of the government is to create a plan for creating a sustainable national economy that can provide a decent standard of living for all Americans.

Sadly, neither political party will support this because Corporate America will do everything it can to protect the tremendous profits offered by Jack Welch’s global business model aka “Factories on Barges”.

Even sadder, most Americans have given up on the notion their representatives in government will ever act in the base interest of the nation when it conflicts with the needs of their campaign contributors. And far too many of us had made ourselves stupid by drinking too much of the free market/free trade/government is the problem/business is the answer Kool Aid our politicos and pundits serve up daily.

We need a progressive Tea Party in support of recreating our jobs base. Its time for progressives to take up their pitchforks and push for the restoration of our economy, so we can continue to afford the rest of our progressive agenda.

Let’s start with a demand for a government-Buy America mandate right now. Make it the key issue in 2012.

Really want to “save” manufacturing ?

It’s simple – Tax givebacks, volume discounts, prefered customer discounts, year end returns, dead peasant insurance, and over seas profits as income.

US corporations offshore to shift profits out of the country and off the US tax codes.

“The biggest component of our decision to shift oversea was our sense consumer markets outside the US offered far better growth potential.”

That explains wanting to sell into those countries’ markets, not wanting to manufacture there. Try another rationalization.

Yves, I know you say wages aren’t a major factor in costs. But I would like to point out something.

When we were a manufacturing country, the product made had tangible value. You could put a price on it and then base that price on how much it cost to produce it with that labor. But now with a knowledge economy when I produce a website or produce a financial statement, all that went into it was thought. There were no raw materials. The only major cost was the software (machinery). So now we have no gauge as to the cost of labor as an input. So the capitalists can pay themselves billions and then pay labor minimum wage.

There are multiple trends at work. First, lack of investment in modern plant and equipment. Example, an ancient factory for Breyers Ice Cream in SW Philadelphia, employed hundreds of workers in a multi-story factory. Unilever, announced plant closure and redeployment of resources to a New England plant on one floor, where inputs come in one side and freezer trucks leave from the other side, with production in between.

Then Mayor Rendell, made a full court press effort to retain a hometown business. After offering the sky, the sun and stars in all forms of tax breaks, special industrial loans and even land in municipal industrial parks next to the PA/NJ turnpikes, he came out defeated. Not that they did not absolutely love how appreciated they were with taxpayer largesse, but the fact was even if they took advantage of everything the city offered, they would s STILL lose money.

The up to date, modern New England plant was not operating at full capacity. By shutting down the ancient and I mean almost 100 year old Philadelphia facility, and adding a production shift, all of the production would be replaced with the pre-existing staff and plant. The foreign competitors are building state of the art plants, using state of the art equipment and are NOT restrained by pre-existing alliances, relationships, and other inter-locking entanglements that keep them from making purely rational decision from a tabula rasa. Thorstein Veblen noticed this same characteristic is the rise of NAZI German industrial production and the wiping out of THEIR unemployment. Their miracle recovery was partly attributed to the Germans coming late to the game that England, France and others had over a century earlier. They could locate their plants and map out their policies without stepping on any toes domestically.

Additionally, as Chalmers Johnson points out with Japan, the surplus capital of the United States went to build them up not only as a market for us, but also as an East Asian show piece of what our system could do for you, as long as you did not ally yourself with the Sino-Soviet model. The architects of American foreign policy never dreamed that Japan or Korea would ever be remotely capable of handling complex, high value, modern technology manufacturing. The worst that they thought we would lose is the shirt button sewing market. Certainly not autos, electronics, heavy equipment.

What else contributes to this de industrialization, other than outsourcing to cut down organized labor’s growing power and take of the profits of manufacturing, is the growing global competition, first from East Asia, then a recovered Europe. Right after WWII it was cheaper to buy a Ford truck made in Detroit and shipped to Germany, than the best, and most efficient producer in Europe could make.

FDR’s plan for a de-colonized world composed of nations, meeting together in the form of the United Nations, and built up and tied together with trade via the World Bank and the IMF, was his GLOBAL NEW DEAL. It is what made new markets for the robust industrial capacity developed during the war effort, now transformed into a multinational source of profits from consumer goods. While we started to lose some manufacturing business to foreign competition, we were the new trade intermediaries, financiers, clearing house, banker and of course, monopoly protection provider in the form of military bases and naval power protecting the world wide reconstruction of multinational commerce.

It is no wonder that there is little regard for widget makers who pale in comparison to the Pax Americana Global Empire. But, I don’t believe now, that the truth has escaped any political leaders. There is a need for manufacturing, if for no other reason than the military policy of national security and global military dominance. No one has abandoned that as a priority policy, even if they don’t believe it is possible given America’s relative decline economically, if not yet militarily.

One final trend, is structural. The profits of finance exceed the returns of manufacturing. So, they let the less profitable places to invest fall to semi periphery countries. The Neo-Liberal G nations have surpassed the United Nation convening as the locus of international relations. And the Gs have grown, from the Group of 6 to the G-7. And now, The UN and the World Bank and the IMF, instruments of American foreign policy, have been eclipsed by WTO, Davos and the G-20 (and counting?). Presently,the nation states relations are dominated with finance, trade and economic issues, as opposed to ideological political struggles and proxy wars that needed containment.

And low profit manufacturing, continually facing mounting competition by each new emerging market, does not provide the rate of return as finance. Capitalism, does not invest to manufacture, it invests to make money. Profits. The investor does not buy to consume, but resell. If it resells paper in the for of oil futures, wheat contracts, what difference does it make to them, if it makes more money than actually drilling, refining or planting and growing. Other people can do that, build up their countries. If we have a strong dollar, we can buy what they make or grow. As long as they accept the dollar in trade. How long should we be holding our breath for that to change?