By Philip Pilkington, a journalist and writer living in Dublin, Ireland

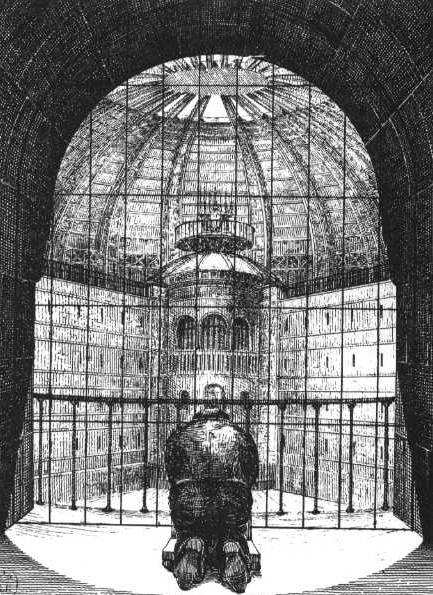

A prisoner kneels before the watchtower in a drawing of Jeremy Bentham’s ‘Panopticon’. The Panopticon was an architectural form that Bentham envisioned for a variety of social institutions. The idea was to have a central platform where an observer could cast their gaze over all the observed, thus making them feel constantly under watch and ensuring, in Bentham’s own words, “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.” Jeremy Bentham is also the father of modern utility theory – a theory often associated with individual liberty, which is actually at heart a blueprint for social control.

It’s not hard to forget just how nonsensical, simplistic and childish the so-called theory of marginal utility is. Personally, I hadn’t encountered it directly for a number of years. But reading a review copy of Steve Keen’s excellent new revised edition of ‘Debunking Economics’ encouraged me to pull out the old Samuelson and Nordhaus textbook once more.

While Keen shows quite clearly in that book that even within its own narrow and absurd definitions the theory is internally inconsistent, I propose here to take a more general look at this intellectual masturbatory appendage that passes for a theory of individual and societal desire – and to try to substantially demonstrate that, far be it from being an expression of individual liberty, it is, in fact, a vision of a controlled and deterministic society, not unlike it’s father Jeremy Bentham’s other invention, the Panopticon.

“But it’s not psychological!”

The theory of marginal utility is, like most concepts in neoclassical microeconomics, quite simple. It begins, also like most concepts in neoclassical microeconomics, with a tautology. The economists claim that people choose that which maximises their pleasure and minimises their displeasure. They refer to this as people ‘optimising their utility’ – ‘utility’ here being this supposedly innate tendency to choose that which satisfies us most.

As any even a half-blind observer will note this is complete claptrap. People often make choices that turn out later not to ‘maximise their satisfaction’ (whatever that crude phrase might mean). Have you ever gone clothes shopping and bought an expensive pair of jeans that you never wore? Well, that’s hardly utility maximising behaviour.

In fact people often make choices that lead to less than satisfactory outcomes. This seems to be by design rather than anything else. If we always made the choices that ensured constant satisfaction we would soon find that we had no motivation to do anything new and would simply sit and stew in our own narrow and static world. That we occasionally make less than satisfactory choices allows us to continue to pursue satisfaction all the more. Nothing would smother our drives, our ambitions and our aspirations quite like a constant state of satiation.

But saying any of this is far too psychological for the average economist. After all, they insist that the theory of utility is not psychological. From Samuelson and Nordhaus’ ‘Economics’ (15th Edition):

But you should definitively resist the idea that utility is a psychological function or feeling that can be observed or measured. Rather, utility is a scientific construct that economists use to understand how rational consumers divide their limited resources among commodities that provide them with satisfaction. (P. 73)

The sheer amount of qualifying statements in those sentences is outstanding. But let us ignore such brazen tautology and meandering qualifying rhetoric for a moment, as there is something far more important and interesting going on here.

Why does Samuelson insist that this is not a psychological ‘function’? After all, we have just shown that the theory of utility contains a strongly psychological dimension in which it gives a very definitive view of human psychology.

This is a classic shunning of intellectual responsibility on the part of Samuelson. He assures us – and with us, himself – that he is not passing psychological judgement. He does this by insisting that we are engaged here in ‘science’ (whatever that means).

Of course, the critical observer can see that this is a strongly psychological argument with absolutely psychological foundations, but Samuelson doesn’t want to know anything about this.

Why? Because that would lead him to be questioned regarding the psychological basis of his assertions and that would cause his neoclassical worldview to crumble, strip him of scientific authority and show him to be doing what he is, in fact, doing; namely, using a scientific ‘style’ to try to convince the reader that the unlikely psychology that he puts forward is in fact objective, scientifically verified reality.

Ever diminishing returns

Adding to the theory of utility the theory of marginality doesn’t really make things any better. The newly constructed theory of marginal utility states that we will derive an ever diminishing amount of satisfaction (that is, utility) from any given product or circumstance.

Impressive, right? Not really. And not strictly true either.

An obvious counter-example would be that of the collector who derives an increase in satisfaction from accumulating a greater number of a certain item. Not to mention the eager capitalist who views money as an end in itself rather than a means to an end and so tries to accumulate ever-increasing amounts right up to infinity.

Eccentrics, surely? Not really. Many people have a passion for collecting a variety of different items and there are certainly no shortage of burgeoning capitalists in this age of popularised stock markets and online Forex trading.

There’s also the issue that advertising can often try to convince consumers to buy ever-increasing volumes of a product – even if the price of the product increases due to the brand becoming more popular. This is often remarkably successful and seems to fly in the face of the theory of marginal utility. In fact, it contradicts it at a very fundamental level. It shows that consumers are not the rationally calculating agents that marginal utility theory says they are. Instead they are agents caught up in trends and fashions and subject to irrational drives that marketers know well how to tap in to.

These objections are not quite as damning as those raised above with regards to utility theory more generally. Indeed, economists will often try to subordinate these secondary objections to their basic so-called laws. In doing so they will bend the ‘laws’ to contain clauses that accommodate for wholly contradictory phenomena.

Such a practice is, in itself, evasive and shows clearly that the theory of marginal utility is not an enterprise in science that attempts to broaden our view of reality. Instead it is an exercise in ideology that attempts to shut down our view of the world and channel all observable phenomena into a few neat assertions – assertions, remember, that were not derived experimentally.

This practice goes right to the heart of neoclassical microeconomics itself. It is, for the most part, a belief system imparted to people to close off how they view reality. In this it is like a strict religion or a cult. Everything can be explained through a few key precepts and when something seems to contradict these precepts we alter the interpretation of the phenomenon itself and make it fit with the precepts rather than questioning the precepts. It’s a bit like a religious fundamentalist endlessly reinterpreting scripture as new phenomena emerge, rather than simply questioning the scripture itself in light of the new empirical evidence.

Although we will look in more detail at this in a moment, it is worth noting here that much of neoclassical economics is in a fact a vast system of collective fantasy. In it the world in all its richness is turned away from and a narrow system of beliefs and assertions is upheld. For the most part, although we will discuss this in more detail in what follows, it appears that this fantasy system is – like many cult systems – designed to ward off anxiety in the adherent and give them a sense of place in the world. That this place is, in a very real sense, malevolent we hope soon to show.

Utility theory slowly builds towards determinism and death

Out of these ridiculous and obviously falsifiable precepts neoclassical economists go on to construct mathematical models. These models say very little beyond the original tautological precepts, but that is not their point. The real point of these models is that they are neat and easy to understand and that they convey the worldview in a way that covers up the dark vision that, in fact, is being imparted to the initiate.

The models show the constraints placed upon the consumer and the possible paths of action that can be taken by him. Samuelson puts it as such:

The fundamental condition of maximum satisfaction or utility is therefore the following: A consumer with a fixed income and facing given market prices of goods will achieve maximum satisfaction or utility when the marginal utility of the last dollar spent on each good is exactly the same as the marginal utility of the last dollar spent on any other good. (P. 77)

Let us remember first that the consumer is supposed to always follow the path to his maximum utility. With that firmly in mind the consequences of the above statement can be fully understood.

What is happening here – contrary to what many would have you believe – is that the economists are trying to establish a deterministic system. They are trying to quash the notion that we are actually individuals who make free choices. Instead we are being viewed here as calculating machines with static preferences that respond to price signals.

Here’s how it works. Neoclassical economists do recognise personal taste (although, as Keen shows in his book, they abolish it when it leads to contradictions), but they view it as fixed, innate and essentially static. We are seen to have fixed tastes in the sense that if we are given a table full of items and the prices of these items are held to be fixed we will always choose certain combinations of these items due to our own static personal tastes.

Change in behaviour only really comes from market signals. When the price of a given good rises or falls, we reorder our preferences – still in line with our supposedly innate tastes, but now accommodating the new price system.

The astute observer can see the determinism here. We are assumed to act, in essence, not only without any meaningful free choice but also as a completely static slave to our drives.

But the idea that people have wholly static tastes is not only offensive, but absurd. Any person who showed such characteristics would be considered beyond simply eccentric – indeed, they would be downright neurotic and chronically so.

Samuelson provides a caveat that sums up exactly this view of people:

What is assumed is that consumers are fairly consistent in their tastes and actions – that they do not flail around in unpredictable ways, making themselves miserable by persistent errors of judgement or arithmetic.(P. 78)

First of all, Samuelson is being far too modest here. If people are not seen to have almost wholly static tastes the theory of marginal utility is worthless. If peoples’ tastes are constantly changing due to personal development, outside influence etc. then price signals will be of secondary importance and psychological and cultural changes will have to brought to the fore as explanations for consumer behaviour toward anything beyond the most simple commodities.

This aside however, Samuelson’s vision of man is quite bizarre. He seems to assume that anyone who doesn’t have static tastes and who doesn’t lead an eccentric and neurotic existence must be ‘miserable’.

Once again we see the psychology that is so unquestionably at the heart of this theory. And what a strange psychology it is. It tells us that we have to learn to do the same thing over and over again ad nauseum, only changing our habits based on price signals (or other costs, such as time expended) and if we don’t do this we will suffer. Beyond being absurd, this is a rather morose vision where the individual is punished time and again for not treading the proverbial hamster wheel of destiny.

This reminds one of the horrifying concept of the ‘eternal return’ that can be found in the writings of the great German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche. A wonderful depiction of this philosophical and literary device was put forward by the Irish writer Flann O’ Brien in his book ‘The Third Policeman’:

He said it was again the beginning of the unfinished, the rediscovery of the familiar, the re-experience of the already suffered, the fresh-forgetting of the unremembered. Hell goes round and round. In shape it is circular and by nature it is interminable, repetitive and very nearly unbearable.

O’ Brien is right, of course. Samuelson’s vision is not one of contentment, but instead one of suffering and interminable neurosis. It is a vision of the ‘compulsion to repeat’ that psychologists have recognised since Freud. The tendency for people – usually neurotic people – to repeat the same thing interminably without deriving any satisfaction from it. Freud, and those that followed him, recognised this as one of the most innately destructive features of the human psyche. Indeed, Freud himself came to view this as a movement by the organism toward death. And yet Samuelson assumes that something similar must be the norm!

Samuelson seems to assume that people will be miserable if they don’t engage in repetitive behaviour because they might make ‘mistakes’. At the risk of sounding a tad corny: are not the most satisfying experiences of life precisely those that come at the risk of error?

This vision, reaching back to Bentham but alive and well in the economics textbooks of today, is far more sinister and grim than the silly little graphs that represent it imply. It is, at heart, a deterministic doctrine that attempts to construct a world in which everything remains in its right place and almost nothing happens. A nihilistic vision of a world of death and purgatory that never truly moves or goes anywhere.

Pretty disgusting theory – why is it so popular?

When trying to understand the popularity of such a vision one cannot help but think of the more perverse of the old religious cults, because in many ways neoclassical economics is a cult of despair and abnegation. That it’s most fundamental psychological underpinnings manifest these characteristics is then of no surprise.

The primary reason that the theory of marginal utility – and to a large extent neoclassical microeconomics more generally – is popular is because it appeals to its adherents as a sophisticated fantasy of control.

This may seem strange. After all, haven’t we shown above that the theory of marginal utility is strongly deterministic? And wouldn’t this seem to imply that the adherent has, in fact, very little control of his life – subject as he is to primitive, static impulses and market price fluctuations? Certainly on the surface that would seem to be the case but scratch a little deeper and we find something a little different.

By being able to conceive of this great system one gains a great deal of power. Or, more accurately, in one’s fantasy one gains a great deal of power. In such a vision of the world everyone’s motivations are wholly transparent and one only need to think about so-called ‘market forces’ to understand the big questions of why everything happens – and where everything should go.

This also puts the neoclassical economist in a seat of power. Imagine for a moment the regal – nay, divine – position these people think they occupy. While the rest of humanity follows their marginal utility, the economists sit back with a panoptic, God’s eye view of the world. Like a sort of dark crystal ball that can be gazed in to in order to understand it all. The power!

The original theorist of utility was, of course, Jeremy Bentham who, as we have noted, also came up with the Panopticon. The Panopticon, as noted, was a totalitarian prison system wherein every prisoner was to be watched constantly by a central observer who monitors their behaviour. Bentham thought that this model could be extended to a variety of social institutions, giving rise to a terrifying vision of a totalitarian hell which was later to be captured in 20th century novels such as Orwell’s ‘1984’ and Huxley’s ‘Brave New World’.

Bentham’s vision was downright paranoid, of course. But it says a lot about the psychology behind his theorising. This man was not a prophet of human freedom and actualisation. No, he was the harbinger of a dark vision of totalitarian control. And his theory of utility was but another manifestation of his own slightly villainous technocratic tendencies.

This is why the theory of marginal utility is still so popular today. It satisfies the controlling desires of its adherents – if only in fantasy. It provides a sort of imaginary Panopticon in which the adherent can sit and watch humanity and ensure that they are acting in the appropriate manner. From such a position the neoclassical can then dictate to governments and populations what sorts of policies should be enacted to ensure that everyone acts as much in line with their fantasies as possible.

And then people tell me that neoclassical economics is the doctrine of individual liberty!? Please! Only a half-educated fool could think such a thing. Neoclassical economics is an advanced system of technocratic control. It has been since Bentham laid down its first postulates, since he first formulated his desires to establish “new modes of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.”

Two nice talks that sort of fit with this topic are Dan Gilbert’s TED talks “Why are we happy? Why aren’t we happy?“, and the follow-up, “exploring the frontiers of happiness.”

While utility theory is not perfect, you seem fundamentally to misunderstand the concept in a way a passage you quote anticipates.

“But you should definitively resist the idea that utility is a psychological function or feeling that can be observed or measured. Rather, utility is a scientific construct that economists use to understand how rational consumers divide their limited resources among commodities that provide them with satisfaction.” (P. 73)

Economics does not claim that utility is a meaningful quantity. In fact, utility is not even really necessary for the theory, and can be expressed (and should be understood as) as a theory merely of preferences between any given consumption pairs at a given time/state. Sometimes, we can use utility functions to make the theory easier to state and more intuitive, depending on the preferences assumed, but one can always go back to the preferences point of view.

Furthermore, the axioms, are just that, axioms, and of course they do not always hold. Where they do not always hold we cannot use the simple proofs available when they do hold. This does not imply that the results of these usual proofs do not continue to hold approximately. Empirically, it has been found, for example, that the hypotheses of the welfare theorems can be significantly loosed without much affecting the outcome much. Extreme cases like violations of the transitivity axiom for preferences only occur in certain sorts of markets which can be studied specifically with this in mind.

Utility theory has it’s flaws (sometime expected utility theory does not seem to work as well as prospect theory), it is a useful tool when applied intelligently by economists.

As I said in the piece the theory does presuppose a psychology. This is then buried by its adherents. When you say:

“…can be expressed (and should be understood as) as a theory merely of preferences between any given consumption pairs at a given time/state.”

The ‘preference’ there presupposed a psychology and that is the psychology of utility. That is the psychology outlined in the first section of the post. The psychology of ‘maximum satisfaction’ and also the psychology of static tastes.

The theory literally means nothing without this psychology. It is assumed throughout. You can’t get away from it.

The funny thing is is that economists are taught to forget about it and push it to the background. But it’s always there.

This is why, when pressed on the matter economists often come out with tautologies like you just did here:

“Furthermore, the axioms, are just that, axioms, and of course they do not always hold. Where they do not always hold we cannot use the simple proofs available when they do hold. This does not imply that the results of these usual proofs do not continue to hold approximately.”

What does that mean in English? It means: “sometime utility theory is true”. Really? I would say never. But even if it is sometimes, that means it is not always true. And if one of the fundamental LAWS of economics is not true — I’m referring, of course, to the downward sloping demand curve that depends on the theory of marginal utility — then the whole foundations are rotten.

“The ‘preference’ there presupposed a psychology and that is the psychology of utility.”

There is a presupposed psychology only insofar as preferences between consumption bundles are assumed to follow certain fundamental preference axioms. These axioms make no mention of utility at all. The psychological activity that is assumed by the theory is merely for an individual to be able to specify whether they prefer one consumption bundle to another, or are indifferent between them. This is not an outlandish assumption about psychology. It can be shown that all utility functions represent a set of preferences, but not all valid sets of preferences can be represented by a utility function.

“What does that mean in English? It means: “sometime utility theory is true”.”

It means that but it means much more. The point is that in cases where it does not hold strictly, where it cannot be proven to hold absolutely because of a violation of an axiom, the result that is observed is reasonably close to the result that would be produced if the axioms were all true. This is obviously not always the case, but it has been shown to be under various circumstances, perhaps the most important being the extension of the Welfare Theorems to incomplete markets.

“But even if it is sometimes, that means it is not always true. And if one of the fundamental LAWS of economics is not true — I’m referring, of course, to the downward sloping demand curve that depends on the theory of marginal utility — then the whole foundations are rotten.”

When I say the axioms are not always true, I mean they do not hold for all types of markets. For some markets, the axioms are always true. In any case this is not the point.

The “law” of downward sloping demand (with respect to price) does not even appear as one of the most basic axioms of consumer theory. In fact, the failure of this “law” to hold for in some cases is a well studied phenomena, and such goods are called Giffen Goods. That said Giffen Goods are extremely rare, so in almost all instances, the “law” of downward sloping demand is true. I suspect you may also be referring to the “law” of “diminishing marginal utility,” which in cases where a utility function can represent consumer preferences says roughly that the second derivative of utility with respect to consumption is negative. This “law” also usually holds, but it is not a fundamental assumption and theory can be build without it. Also, it can still apply where no representative utility function exists, because stated generally, the requirement is only the preferences be convex, which does not depend on utility. This assumption is also not a fundamental “law” really. It is the preference axioms which are most fundamental.

“The psychological activity that is assumed by the theory is merely for an individual to be able to specify whether they prefer one consumption bundle to another, or are indifferent between them.”

It’s more than that. As Samuelson says (quoted above) these tastes must also be static. They must not shift through time.

“This is not an outlandish assumption about psychology.”

Yes, when you take into account that these tastes must remain static it is.

“The point is that in cases where it does not hold strictly, where it cannot be proven to hold absolutely because of a violation of an axiom, the result that is observed is reasonably close to the result that would be produced if the axioms were all true.”

Behavioral results have disproved this.

“The “law” of downward sloping demand (with respect to price) does not even appear as one of the most basic axioms of consumer theory.”

See comment below. Samuelson introduces downward sloping demand curves on the same page. The whole above quotes are pulled from the chapter ‘Demand and consumer behavior’ and this chapter deals with marginal utility and then moves onto ‘Why demand curves slope downwards’.

The two theories are dependent on one another. Look it up.

Another quote from Samuelson (same page):

“Therefore, a higher price for a good reduces the consumer’s desired consumption of that commodity; THIS SHOWS WHY DEMAND CURVES SLOPE DOWNWARDS.”

Note that the first half of the statement is the marginal utility theory, the second half leads is WHY DEMAND CURVES SLOPE DOWNWARDS.

Ben said, “Utility theory has it’s flaws (sometime expected utility theory does not seem to work as well as prospect theory), it is a useful tool when applied intelligently by economists.”

Utility theory can indeed be “a useful tool when applied intelligently by economists” but when it is the findings are shunned by the mainstream of textbook and “big name” economists.

The assumptions used in marginal utility theory — for example the rational maximizer of utility — are not at all realistic and economists will readily admit as such. But there are both strong and weak forms of the standard assumptions and one of the favorite evasions of the economist is to employ the strong form in the model and justify its quasi-realism with the weak form. The “strong form” and the “weak form” are chalk and cheese, though. There’s no correspondence between them. They are qualitatively different states, not different intensities of the same quality. Like blue and red are both colors but blue is not a “darker” red. The maximizer and the individual who “often behaves as is he was a maximizer” are incommensurable. The latter’s utility function cannot be calculated. It’s as simple as that.

The one case where utility theory makes the most sense is the one most studiously ignored by economists. This is the demonstration that rational actors pursuing their self interest in a perfectly competitive market can only achieve an efficient outcome with the additional (non standard) assumption of “complete information.” This means they would have to have perfect knowledge of not only their own utility curves but everyone else’s, along with knowing that each other person knew every other person’s utility curve.

Universal God-like omniscience is NOT a standard assumption of marginal utility theory. It is a tacit, supplementary stipulation required by the efficient market hypothesis as well as the mixed-economy mathematical hocus-pocus of the Samuelson neoclassical synthesis. The algebraists of the 1930s had to go through quite a few contortions and anachronistic diversions to cobble together their synthesis: “…a mobile army of metaphors, metonyms, and anthropomorphisms…”

Mr. Pikington

Even this –

Another quote from Samuelson (same page):

“Therefore, a higher price for a good reduces the consumer’s desired consumption of that commodity; THIS SHOWS WHY DEMAND CURVES SLOPE DOWNWARDS.”

– is incorrect.

In fact, raising the price of certain goods can often raise the demand for them. Can’t put my finger on the source right now, but I believe it was in The Economist where I read an article a few years back that showed people were more apt to buy wines and other luxury goods the more expensive they were. Obviously this is due to psychology. I’m not sure how scientific the study was or how big the sample size, but hey, it ought to be good enough for your typical economist!

This simple fact was known to me long before reading it in The Economist as I was a waiter for many years. I can attest that an extremely small number of people ever ordered the least expensive bottle of wine on the menu and I was able to use that for my own gain on many occasions. There is very little difference in quality between a $25 bottle and a $50 bottle of the same vintage yet it was not difficult at all to convince people that the $50 bottle would make their meal better since the vast majority of people know very little about wine.

If marginal utility were true, the restaurant industry would be next to non-existent since nearly everything at a restaurant costs more than simply buying the food and cooking it yourself.

Ben, you seem to be attempting to dazzle the crowd here with technical jargon. I don’t think many here are fooled. Mr. Pikington is correct in that these economic theories, and I use the term extrememly loosely, completely fall apart when human psychology is taken into account.

The only time that may be somewhat applicable is when people don’t have enough money to make ends meet and must buy the cheapest alternative. And even then people do not and will splurge on occasion so as not to be seen as poor.

Clearly having the majority of people in poverty is not the optimal situation from a purely economic standpoint as people will not be able to buy many of the goods and services others would like to produce. The less $ the majority has means less $ that can be extracted from them by the wealthy, who will eventually see their wealth diminished. Of course it’s all relative – if the economy collapses, even a billionaire reduced to a millionaire will still be able to buy and sell the majority many times over. But then it’s really a question of power more than amassing the largest sum possible for yourself, isn’t it? And then we’re right back to the psychology of what really makes people tick.

All I can say is you can try to blind people with economic “science”, but there is none so blind as he who will not see.

Excuse me, but utility is not axiomatic. In fact, the whole point is that human nature is full of contradictions and idiosyncrasies that make utility the exception instead of the rule. Even with basic commodities like rice and wheat there are personal and cultural preferences that override “price signals” and the claptrap that surrounds them. Philip is quite correct. The whole edifice of neoclassical economics is flawed.

That utility is not axiomatic in economic theory is precisely the point I am making. Preferences are axiomatic, in that they are assumed to follow a set of axioms which may not be true in every situation. They hold well enough in a large number of circumstances to produce useful results.

So preferences are axiomatic in that they follow from certain other axioms — and what pray tell are those axioms that form the basis of the preference axiom?

The four fundamental axioms are:

1) (Completeness) For any consumption bundles A and B, either A is preferred to B, or B is preferred to A or regarded as indifferent to A.

2) (Reflexivity) For any consumption bundles A and B, if A = B, then A is (weakly) preferred to B. Weakly means it A is preferred to B or A is regarded indifferently to B.

3) (Transitivity) For any consumption bundles A, B, and C, if A is preferred to B and B is preferred to C, then A is preferred to C.

4) (Continuity) For any consumption bundles A, B and C, if A is preferred to B, there exists epsilon such that if the difference between B and C is less than epsilon, A is preferred to C.

“The four fundamental axioms are…”

Note that all of these so-called ‘axioms’ depend on static and definable tastes — because all these axioms are based on utility theory. We dealt in a comment above about why static tastes are idiotic. And what about definable tastes. I’ll reiterate from the piece:

“In fact people often make choices that lead to less than satisfactory outcomes. This seems to be by design rather than anything else. If we always made the choices that ensured constant satisfaction we would soon find that we had no motivation to do anything new and would simply sit and stew in our own narrow and static world. That we occasionally make less than satisfactory choices allows us to continue to pursue satisfaction all the more. Nothing would smother our drives, our ambitions and our aspirations quite like a constant state of satiation.”

One more note on this aspect because I know some joker is going to chime in and claim that demand theory can be articulated without the utility theory. This is absolute nonsense. Consider Samuelson:

“A century ago, the economist Vilfredo Pareto discovered that all the important elements of demand theory could be analyzed without the utility concept. Pareto developed what are today called indifference curves.”

I’m not going to go into the nitty gritty here, but what follows shows just how sloppy a thinker Samuelson was.

On the very next page Samuelson talks about the ‘Law of substitution’. This is absolutely fundamental for the indifference curves to work. Now, remember indifference curves, according to Samuelson, show that “all the important elements of demand theory could be analyzed without the utility concept.”

But what does Samuelson do? Well, he drags back in the utility concept. Again note, this is literally a few paragraphs down from his assertion regarding the redundancy of utility theory.

“The slope of the indifference curve is the measure of the goods’ relative MARGINAL UTILITIES, or of the substitution terms on which — for very small changes — the consumer would be willing to exchange a little less of one good in return for a little more of the other.”

The indifference curve is, at best, another means of demonstrating the psychological assumptions of utility theory. At worst, it is just utility theory in disguise.

We still have the vision of the consumer that responds to static choices and prices, trying to get as much bang for their buck as possible. In short, we still have the lifeless parody of a neurotic bargain hunter who gets nothing else done because he spends his time stalking the budget shelves of outlet stores.

@PP 7:13

Err. they don’t?

The axioms say absolutely nothing about time. I could very well rewrite tham “at time t… ”

I haven’t met any economist who would say that the demand curve/preferences etc. are static in time.

What I can say is “there exists a set of people S, such that they prefer good A”. S doesn’t depend on individual people – members can leave and join (as they will), by either dying/being born or a simpler feat of changing preferences. As long as there’s good A, there are people who prefer it to some other goods (assuming it’s not the only choice) – otherwise there wouldn’t be A.

Indeed, the whole demand curve stuff is based on the set not being static – you just say economy allows it to change due to the price only. I’d strongly dispute that (if nothing else, economy recognizes supply/demand shocks, which drive price – so it’s not the price that is driver, but something else).

@ vlade

For the last time… Samuelson says that consumer tastes must be relatively static. So, if you want to hear an economist say this READ SAMUELSON or just READ THE QUOTES IN THE PIECE.

AGAIN AND FOR THE LAST TIME. Samuelson:

“What is assumed is that consumers are fairly consistent in their tastes and actions – that they do not flail around in unpredictable ways, making themselves miserable by persistent errors of judgement or arithmetic.”

If tastes are not assumed to be fixed for every individual person then the term ‘utility’ (i.e. maximum satisfaction) is completely meaningless because their satisfaction with a given product will change through time.

If this is true then they are clearly not making decisions based on so-called ‘utility’ but instead are making decisions based on whims and the like. Thus they ARE NOT CALCULATING. And they are NOT CONSUMING IN THE RATIONAL MANNER THE THEORY ASSUMES.

This is not complicated at all. It really isn’t. Either people have set preferences which they try to maximise through price movements (the utility argument) or they do not. If they do not, the utility argument is bunk. Really simple.

Again this shows that it isn’t that economists cannot understand, it’s that they don’t want to understand because it f&*ks with their totalitarian worldview where they can ‘understand’ people’s consumption decisions.

(P.S. Your supply/demand argument is tedious. Everyone knows that market prices [supposedly] reflect suppl/demand. That was implicit in all my statements.)

“…so it’s not the price that is driver, but something else…”

Actually I should clear this up, because that supply/demand stuff you just wrote is very sloppy.

Yes, the price is driven by ‘something else’. That is (if you’re a neoclassical): the interaction between supply and demand. Since we’re only dealing with the demand side in the piece we can say what the driving force is (supposedly)… wait for it…

Marginal utility… duh! That’s what we’re talking about.

I’m saying that the term ‘marginal utility’ is meaningless because people don’t consume in line with ‘maximum satisfaction’. They don’t consume in line with static preferences. And — hence — they don’t consume in line with so-called ‘marginal utility’. Because ‘marginal utility’ is a meaningless phrase that attributes a dumbass psychology to the individual which they do not possess.

Wow, the swearing and the CAPITAL LETTERS are finally out.

I’ll tell you what is tedious…

I mean, seriously, look at one of the first paragraphs here: “As any even a half-blind observer will note this is complete claptrap. People often make choices that turn out later not to ‘maximise their satisfaction’ (whatever that crude phrase might mean). Have you ever gone clothes shopping and bought an expensive pair of jeans that you never wore? Well, that’s hardly utility maximising behaviour.”

Do you really not see the lapse there? That’s not a counterargument, do you see that? Requiring that everyone have a crystal ball about the future does not disprove the idea that people often make choices that they think will be better than the alternatives, even if they don’t work out as the future unfolds. The future is uncertain, you do understand that, right?

You do understand that even if the fundamental basis of economics (and most economic analysis) is flawed, you can still look really foolish by writing paragraphs like you did above?

And your responses to these commenters…it’s not helping. Seriously. Your lack of humility and your lack of appreciation for the huge ideas you are trying to grasp is…well, foolish is the only word I can think of.

Whatever. If this is maximizing your utility, go ahead.

The axioms are carefully chosen so one can do math with preferences, not because they reflect what people really do or how they behave.

The big problem with macroeconomics in particular is that it is VERY hard to do experiments, and without experiments its very hard to test the predictions of your models, and if you can’t test the predictions of your models, you can’t figure out which models are wrong and which ones make sense.

All the hand wringing by macroeconomists (at least the ones who have been paying attention) is, I think, due to the fact that their models utterly failed to even hint at the current mess the worlds advanced economies find themselves, and they fail to provide any useful guidance on what to do about it. It’d be like proposing Newton’s law, only to find that it doesn’t predict anything, and that you can’t use it to do any engineering. In other words, the models are wrong.

“Requiring that everyone have a crystal ball about the future does not disprove the idea that people often make choices that they think will be better than the alternatives, even if they don’t work out as the future unfolds.”

Yes, it does. because utility theory depends upon people deriving the ‘maximum of satisfaction’. That’s really very clear.

The fact that the future is uncertain does, in fact, do it damage. Because we need to be pretty much certain about what satisfies us if we are to be able to ‘maximise our utility’. I don’t think you’ve grasped the arguments here…

You are correct only in the narrowest way possible. There are many economic models which use different assumptions. Some models use such simple agents and they can give us very useful predictions. Some other models use much more complex assumptions to account for time lag, uncertainty, etc… You are complaining that economics is not describing reality. But that’s not the goal. The goal is to model reality. Models necessarily involve some simplifications. The important question is not whether those simplifications are realistic, it is whether those simplifications give us good predictive models. Sometimes, the answer is yes, sometimes the answer is no. It’s that simple and involves neither totalitarian tendencies nor stupidity or dishonesty.

“Furthermore, the axioms, are just that, axioms, and of course they do not always hold. Where they do not always hold we cannot use the simple proofs available when they do hold. This does not imply that the results of these usual proofs do not continue to hold approximately.”

As I was schooled during my PhD candidacy exam, if the assumptions underlying the proof do not hold exactly, the results of the proof cannot be assumed to be even approximately correct. You can’t say anything about them: in particular, saying “the assumptions are sort of correct so the results are approximately right” is pure junk reasoning and easily refuted. In the case of microeconomics, the results must be judged empirically. Finding counter-examples to the theoretical results of marginal utility (which exist) implies that assuming the results generally hold is just a hobby, not science.

You are misunderstanding me. Of course, one can not make such a logical leap. What I am saying is that their is empirical and theoretical evidence that in a number of particular cases, the small deviation in assumptions produces small deviations in results. This is by no means assumed. It is shown for any such case.

Also, the statement you quoted is absolutely true from a logical perspective. In it I made no claims that the axioms were unnecessary for the truth of theorems based on them. I said only that the theorems may hold without some axioms. They may not as well, and I did not state otherwise.

You are saying less and less with more and more words. What axiom is at the basis of this phenomenom?

Let me try to make the statement more clear. It is really something with which I’m sure you’d agree. If a set of axioms A can be used to prove a logical statement S, and an a subset B of A is false, S is not proven with the original proof, but whether or not S is true we cannot say based on this information alone. It is possible in particular instances that we may be able to produce a proof that S is always false if B is false. It may also be possible in some instances that we can prove that A\B is sufficient to prove S. Or we may know of know proof either way.

Be careful. You’ve sent him into ‘economist spouting tautology mode’. It’s a downward tailspin from here…

In other words, something may be true or may not be true, and we might be able to prove its true, or might not be able to prove its true.

It seems to me you are just saying that context is everything and therefore the “laws” that Samuelson and neoclassical economics take for granted are not laws at all — they are mere assertions that may be more false than true.

Thanks for the warning Philip :) And thanks for more of your excellent debunking of the utter claptrap that is neoclassical blah blah economics.

We should be able to clear this misunderstanding up with a little bit more Samuelson. (It’s amazing how many economists don’t ACTUALLY understand why certain theories are necessary for the neoclassical edifice to function as theoretically sound).

I quote Samuelson above:

“The fundamental condition of maximum satisfaction or utility is therefore the following: A consumer with a fixed income and facing given market prices of goods will achieve maximum satisfaction or utility when the marginal utility of the last dollar spent on each good is exactly the same as the marginal utility of the last dollar spent on any other good.”

He continues:

“Why must this condition hold? If any one good gave more marginal utility per dollar, I would increase my utility by taking money away from other goods and spending more on that good…”

Do we see what is happening here? Tastes are assumed to be fixed. As the price falls the FUNDAMENTAL RULE (yes, Samuelson calls it this, give me a moment…) states that people must ‘automatically’ take money away from the now more expensive goods and channel it into the cheaper good.

This assumes a very specific psychology and that is the psychology of the utility-maximizing individual. The individual whose choices are based on utility-gains above all else.

Now why is this so fundamental. Well, as I said above the ‘LAW’ — absolutely fundamental for neoclassical economics — of the downward sloping demand curve depends on this. Samuelson again:

“Using the FUNDAMENTAL RULE [of consumer equilibrium based on marginal utility and prices] for consumer behavior, we can easily see why demand curves slope downwards.”

And voila! Neoclassical economics finds its downward sloping demand curve. To remind everyone this is the first half of the supply-demand equilibrium that neoclassicals hold up as a holy law. If one side of this is even remotely flawed, the whole edifice falls apart.

Shocking though that most economists don’t even understand this. They really think that all the pillars in neoclassical economics stand or fall on their own.

It is rather obvious to an observer that this law does not work. We do purchase items on the basis of price only partially, namely if products are really 100% equal. To name a product that is successful on the exact opposite of this economic law, look at Rolex. People want a Rolex exactly because it is expensive and because the firm instilled in the market that prices will only go higher not lower. This idea makes the product very attractive to many buyers. It would be easy for this company to produce many more watches and at much lower prices but they use an upside down approach when looking at this economic theories.

Meaning, they may produce a higher quantity of watches for a short period after which they will lose that most important advantage and I am certain, the short term profits of producing higher volume would expire rather soon and volume would collapse even as prices are much lower.

In other words, we buy a product on the basis of what it represents emotionally and on what we think is the society’s value scale associated with a product. The actual value often becomes secondary but the image it transports is more important in many cases.

The important thing to realize is that economics makes no claim of what the “actual value” of a Rolex watch is. Utility properly understood merely ranks goods according to preferences. Whatever preferences people have over Rolex watches determines their “value” as far as consumer theory is concerned. These preferences can take into account any emotional value you like.

I think that luxury items – like a Rolex watch – are anything but rational purchases, unless the rationale is to increase your social standing (like a more brightly feathered bird) thereby bettering your position in the pecking order and attracting a better (trophy) mate.

The rational utility here is pure reptilian biology. Our most primal yearnings have long been used by marketeers to shill just about anything.

The very idea that psychology plays no part in our buying decisions is truly insane.

If classical economics is built on such a shaky foundation then it is not hard to understand why so many people who believe that Adam and Eve frolicked with dinosaurs 6000 years ago in the Garden of Eden also claim to be Free Market fundamentalists. A rotten apple doesn’t fall far from the Tree of Knowledge.

Samuelson is being slightly loose in his use of language, in that much of what he says could be expressed without resorting to the concept of utility, but leaving that aside, your problem with consumer theory appears to be that “preferences are fixed” (I presume you mean with respect to prices). Imagine if this were not the case. Then construct new consumption bundles which are pairs of what were previously considered consumption bundles, and prices. The preferences over these new consumption bundles will be fixed in the necessary manner. In any case, as I have already said, demand curves which are not downward sloping are handled just fine and are called Giffen goods.

“Samuelson is being slightly loose in his use of language, in that much of what he says could be expressed without resorting to the concept of utility…”

No, it cannot. People need to respond to prices almost perfectly in line with their static preferences in order for demand curves to slope downwards. If they responded in any other way, the demand curve would be unpredictable. Which leads to…

“Imagine if this [i.e. non-static preferences] were not the case. Then construct new consumption bundles which are pairs of what were previously considered consumption bundles, and prices. The preferences over these new consumption bundles will be fixed in the necessary manner.”

No, by definition they would not be fixed. You’ve just said: “Imagine if the bundles were not fixed. Now constitute new bundles. They are now fixed.” That’s a tautology (once again).

The point is, if you send someone into a shop and ask them to choose fifty items and then send them in shopping again they will probably come out with different bundles. This wreaks havoc on the theory because it means that people respond to other factors that are far more important than price movements. They won’t just be watching prices. Instead they’ll be responding to different personal choices as their tastes change through time.

I’m not discussing Giffen goods here. That’s off topic.

We’ll quote Samuelson (again), note that this is included in the piece:

“What is assumed is that consumers are fairly consistent in their tastes and actions – that they do not flail around in unpredictable ways, making themselves miserable by persistent errors of judgement or arithmetic.”

Economists make no claim that preferences must be fixed over time. I took you to mean fixed over price. Over time, nothing prevents someone from changing his or her preferences.

“You’ve just said: “Imagine if the bundles were not fixed. Now constitute new bundles. They are now fixed.” That’s a tautology (once again).”

If this is your interpretation of what I said perhaps I have not been clear enough. First we have a bundle, say a vector of good quantities Q. Now what I am saying is that if we construct a new bundle B = {Q, P}, where P is the vector of good prices, and look at preferences over B, they are fixed relative to time.

““What is assumed is that consumers are fairly consistent in their tastes and actions – that they do not flail around in unpredictable ways, making themselves miserable by persistent errors of judgement or arithmetic.””

Here Samuelson is again using loose language. Strictly we only need consumers not to flail around in the decision they would make at the exact same moment. Stability of preferences over time can be used to prove various additional things, but it is by no means necessary for consumer theory.

“Strictly we only need consumers not to flail around in the decision they would make at the exact same moment.”

That doesn’t make any sense. How would a consumer ‘flail around’ in a decision that is already made? If they make a decision at a given moment then, by definition, they are not flailing around. The above is a meaningless sentence insofar as it doesn’t seem to understand what the term ‘decision’ means…

“Stability of preferences over time can be used to prove various additional things, but it is by no means necessary for consumer theory.”

It absolutely is and Samuelson says it — but you dismiss this as if he doesn’t know what he’s writing.

That doesn’t make any sense. How would a consumer ‘flail around’ in a decision that is already made?

Obviously they are referring to multiverses. Neoclassical economists were intuitively (devine inspiration?) aware of theoretical cosmology before cosmologists. In an alternative universe another you would make the same decision at any given simultaneous moment when confronted with the same good bundle. Duh!

For this very reason I would not have chosen the phrase “flail around,” but think of it as meaning, roughly, that preferences are not random variables.

Samuelson is basically referring to a special case of a more general theory than he explicitly outlines, and he is not making his statements with absolute mathematical rigor, because his goal is pedagogical. Frankly, a better source document would be a more rigorous statement of the general theory from the literature.

“Frankly, a better source document would be a more rigorous statement of the general theory from the literature.”

I’m not playing that game. Then no-one would understand what I was criticising. Evasion of the Schoolman variety.

“…but think of it as meaning, roughly, that preferences are not random variables.”

Yeah, I think of the concept that way too. The problem is that many preferences are pretty much random variables. People often make choices fairly randomly and not subject to any rationality or utility-maximising preference. That was precisely the point of the piece. That is the ‘psychology’ I keep talking about and you keep evading by bringing up irrelevant technical details.

The thing is many of the technical details are relevant to your argument.

If you are arguing that someone who has read only Samuelson’s textbook may sometimes misapply economic theory and come up with incorrect results, I agree with you. Fortunately, economists usually know better.

Actually, that last comment deserves a requote from the piece — because this is just SOOOO typical:

“Of course, the critical observer can see that this is a strongly psychological argument with absolutely psychological foundations, but Samuelson doesn’t want to know anything about this.

Why? Because that would lead him to be questioned regarding the psychological basis of his assertions and that would cause his neoclassical worldview to crumble, strip him of scientific authority and show him to be doing what he is, in fact, doing; namely, using a scientific ‘style’ to try to convince the reader that the unlikely psychology that he puts forward is in fact objective, scientifically verified reality.”

@Ben

Please respond to this and stop naval-gazing about how much more you know about the abstract entity known as ‘economic theory’:

“Ben: …but think of it as meaning, roughly, that preferences are not random variables.

Phil: Yeah, I think of the concept that way too. The problem is that many preferences are pretty much random variables. People often make choices fairly randomly and not subject to any rationality or utility-maximising preference. That was precisely the point of the piece. That is the ‘psychology’ I keep talking about and you keep evading by bringing up irrelevant technical details.”

@Phil: It does seem pretty dishonest/lazy to pick out small bits of a text from a single economist’s text, claim that idiosyncrasies in his explanation are widely held and fundamentally the core beliefs of economists, and then critique all economics based on a few sentences you sniped from the book……all because you think economics is so simplistic/atomistic as to be absurd.

I mean, hypocrisy doesn’t make you wrong, it’s just weird that what you have such a problem with when it comes to economics, its oversimplification to the point of not even reflecting reality and thus being useless, is how you chose to set up an argument against economics: oversimplification to the point of not reflecting the theory, but then claiming it doesn’t matter.

@ Erv

I didn’t just ‘snipe’. I critiqued the major introductory text. Referenced other critiques and responded to critical comments. I don’t see how I could do more.

Your comment is very wishy-washy. It just assumes that ‘somewhere out there’ is a sufficient rebuttal. In that it is akin to faith rather than reasoned argument. If you are happy with faith and find it well placed in a watery and depressing doctrine that’s fine. My arguments are aimed at people with open minds that are receptive to reasoned argument.

@Phil: You said “I critiqued the major introductory text.” So this is a good point. You did critique A major INTRODUCTORY text. By Samuelson. So at best, you have critiqued introductory ideas in a given textbook from a single economist. I think it is suspect for you to try to pull out a critique of all economics from such a directed critique, even assuming that you have done a perfectly adequate job of such a critique, which I don’t think you have.

Ben in turn tried to argue with you and engage on this broader level that you seemed to want to go…that is, talking about economics as a whole. When he presented you with a richer understanding or interpretation beyond what an introductory text had to offer, you defended yourself by falling back into Samuelson alone. So either you want to debate whether Samuelson is right or you want to have a broader discussion about economics as a whole. But if you want to broaden the scope of your points, it seems like a mistake to keep insisting that we only discuss Samuelson. If that’s all you want to do, congrats, again you have at most critiqued a single, if widely used, text by a single economist.

Many economists would agree with you that introductory texts are insufficient (Brad Delong posted on this recently) and in some cases worthless for the most part. Some are not much more than right-wing propaganda (looking at you, Mankiw). I would agree that most need to be rewritten to address concerns like yours. That is, we agree, the text is wrong, but that doesn’t make economics wrong.

I’m sorry you want to only discuss Samuelson, because it seems like there is a rich discussion to be had here. But if you can’t move beyond insisting we only talk about the exact words of Samuelson, then all we’re doing is talking about one introductory textbook.

That said, I do have opinions on this beyond simply a meta discussion…I might actually go a different direction from Ben and flat out disagree with you that people are as unique as you claim for the most part. The freedom to choose a different set of 50 items each time I enter a wal-mart isn’t a very appealing idea of freedom or idea of what makes me a unique individual. At the same time, I still mostly buy the same crap over and over: detergent, pbj and bread, tshirts, shoes. The world can still be a beautiful and complex place even given my banal purchases that economics does a good job of modeling.

“So this is a good point. You did critique A major INTRODUCTORY text. By Samuelson. So at best, you have critiqued introductory ideas in a given textbook from a single economist.”

So, then the theory of marginal utility that is being taught in the most read introductory textbook ever written is incorrect? Okay. Fine. I’m cool with that. That, to me, raises questions about the theory. If you’re happy to believe otherwise then carry on…

You are being remarkably obtuse. Samuelson was one of the most important forces in defining what proper methodology was for economics. And Pilkington is 100% correct in saying tastes must be static over a consumer’s lifetime. I discuss how that is necessary for the proofs to work in my Appendix 1 in ECONNED. Steve Keen has a longer-form discussion in Debunking Economics.

It’s even worse than he suggests: tastes are consistent across ALL consumers. The classic proof rely on a single consumer to stand for all! I am NOT making this up.

Your statement is simply untrue. The onus is on you to show Pilkington is wrong He’s provided references. Where are yours?

“Extreme cases like violations of the transitivity axiom for preferences …”

Hilarious. In everyday life, of course, transitivity of “preferences” is violated massively and constantly.

Yes, it’s true that Samuelson was trying to banish the dependence of economic theory on utility (and Philip is perfectly correct to say that the psychological assumptions merely went underground). So now we have “revealed preferences”. That’s supposed to be “scientific”? How about “magical”?

RP has been taken apart by internal critiques by Sen and especially Stan Wong. But that doesn’t end the problems. It rests upon a complete logical fallacy, for one thing. Secondly, “preferences” are intensely context-dependent, as a moment’s thought will demonstrate. And anyone who has actually done empirical and historical work to determine what the goals, aims, intentions, desires, etc. (“interests”, “utilities”, “preference orderings”, “probability assignments”) of real people are knows damn well how hard it is, even with a deep familiarity with and examination of all the available historical evidence. And how ridiculously facile it is to infer a specific set of “preferences” from actual behaviour (simplistically and often falsely rendered as “choices”) — let alone to then take that inference and generalise it as some portfolio of preferences that agents take with them and consult from one context to another. I’m not a big fan of blanket philosophical theories like the so-called “Duhem-Quine” thesis, but here it applies with spades. There is literally an infinite number of perfectly consistent and perfectly plausible sets of “preferences” one could attribute to a person based on examination of any one set of actions.

“This does not imply that the results of these usual proofs do not continue to hold approximately.”

Oh yes, “approximate truth”, that all-purpose get-out-of-jail-free card. What “approximate” actually amounts to is never defined, of course. The fact that slight changes in parameters can completely reverse causal patterns is never acknowledged. The fact of the matter is this: axiomatically derived conclusions hold only — only! — in systems which exactly correspond to the model’s assumptions. “Approximation” and “external validity” can *never* be assumed, and must be demonstrated, empirically, case by case; even then, “empirical fit” doesn’t necessarily say anything about the correctness of the model. (Actually, I’d make a stronger argument, but that’s enough for now….)

You seem to have a peculiar definition of the word “axiom”.

I have the definition used in math and economics. Axioms are assumptions on which a larger theory is built. We do not claim that they must hold, but only show what can be inferred if they do.

Even in the mathematics of set theory, there are multiple axiomatizations. This is not a flaw.

I call bullshit.

An axiom is a statement that is posited to be true. You can’t have axioms that are only true when it is convenient for people like you.

Let’s look at Euclid’s axioms of geometry. One of them, the parallel postulate, can be removed, and we can develop a non-euclidean geometry which is the basis of much of modern physics. Was Euclid wrong? No, his theory is absolutely correct for his chosen axioms, which are in turn extremely reasonable in many situations. I think you likely agree with what I am trying to say in defining axioms, as what I mean to say has no important consequences, but is merely a question of semantics. Perhaps I am being insufficiently clear.

By the way, while many of your comments suggest that we probably have a number of disagreements, I look forward to reading your book, in part because one must always guard against confirmation bias, especially in areas about which one has long-held views based on his training in a particular field. My respect for Harry Shearer also compels me to take your book seriously enough to read. I suspect I will be making a lot of notes with my kindle on points of disagreement, but such a process is a healthy exercise.

Wow! Your belief in the superiority of your intellect is downright delusional.

From your grandiose perspective, do all the counterarguments to your faith presented here simply corroborate your exceptionalism instead of encouraging any reassessment of your beliefs?

Mille regrets for reminding you that you are just another biased and mistake-prone human being like the rest of us.

You seem to have interpreted my post to mean roughly the opposite of what I intended. It is because I recognize I am not all-knowing and have bias that I intend to read ECONned. I want to expose my beliefs to criticism to test and modify them as necessary.

Independent of Ben’s other statements, but his usage of “axiom” is indeed the standard modern one, and should not be so criticized.

The purpose of axiomatization is usually organizational, to clearly identify assumptions and rigorously & systematically present arguments in standard terms and forms. The truthiness, the applicability of these assumptions and their consequences in a particular situation is another question.

I vaguely recall the Theory of Marginal Utility as a justification for PMs for money. If I recall, once one has enough shiny metal to satisfy his need for shininess then it makes sense to use any additional shiny metal one obtains to trade with other people so they can satisfy their need for shininess.

Great analysis, Yves

you should probably look at the title of the post again. ;)

oh, sorry

It’s a bit like a religious fundamentalist endlessly reinterpreting scripture as new phenomena emerge, rather than simply questioning the scripture itself in light of the new empirical evidence. Philip P

Actually, according to Christianity, Scripture itself is “Living”. That could mean via new inspiration from the Holy Spirit or perhaps the actual text changes if one assumes that God can act in the past as some do. For instance, if I pray for a $100 today and a check for that amount arrives 15 minutes later in the mail, did God know a few days in advance I would pray for $100 or did He act in the past as soon as He heard my prayer so that the check would be sent early enough?

But I note that Calvin “reinterpreted” away the prohibition against usury between fellow countrymen in Deuteronomy 23:19-20. He turned out to be wrong, imo. So Scripture 1, Calvin 0.

Calvin can reinterpret my ass hairs as his fur coat. A hateful man with a hateful plan.

A hateful man with a hateful plan. YankeeFrank

If you mean “Dominionism”, I agree. Christians are to influence by example not by unjust power over others.

Dominionism is bad, yes, but predestination, “total depravity”, all of it, is a life-denying horrorshow based on notions of an exclusive “elect” versus those “not elected”. Jesus was way cooler than all that.

Agreed. People should just read the Bible for themselves, in my strongly held opinion. Every church I’ve attended from Roman Catholic to Baptist including the Calvinists have managed to misinterpret Scripture. The Calvinists are the prickliest and most arrogant though. Poor things!

In all fairness to Bentham, the Panopticon was supposed to be a humane way of reforming criminals, not a Brave New World.

Bentham was responding to the fact that people convicted of a variety of crimes were subject to all kinds of bizarre and brutal punishments that did nothing to actually ‘help’ them to adjust to normal behaviour (i.e. *not* stealing, *not* killing, etc.).

The Panopticon was supposed to help people internalise the prevailing norms of society as to what was acceptable and what was not *without* there being any physical brutality or coercion. You always had the option to *not* internalise social norms, but then you’d not be let out.

I’m not saying that that this isn’t a frightening vision, but it wasn’t a system of control and should be understood in its proper context.

Bentham is quoted directly above:

For him the Panopticon is “a new mode of obtaining power of mind over mind, in a quantity hitherto without example.”

You can tell Jeremy Bentham to ‘get stuffed’, but it would be redundant; he is displayed fully stuffed at the University College of London.

Actually, its a system of total psychological control. Imagine always being watched and judged, and in a cage. If you behave in that cage according to the accepted norms (whatever they are for someone in a cage) you may be let out at some point in the future? Its a softer form of brutality that doesn’t perhaps leave physical marks but I’d imagine many people would rather be whipped and water-boarded than have to put up with that for any amount of time.

It seems that every time a British philosopher promoted some school of thought to underwrite the power and wealth of the empire, they were rehashing Plato. Of course, no person would pick what is anything other than what is good for him/ herself, even trying to maximize benefits of the choice. The problem is: How do you know what is really good for you, and not what seems good? And of course, what if what is good for me in reality comes at the expense or loss for someone else? Cui Bono?

>> But you should definitively resist the idea that utility is a psychological function or feeling that can be observed or measured. Rather, utility is a scientific construct that economists use to understand how rational consumers divide their limited resources among commodities that provide them with satisfaction. <<

Wow! So much bullshit, all tightly packed in two average length sentences! Now, that's quite an accomplishment.

Thank You Philip Pilkington … I have long followed Steve Keen and you have captured a most important point, the fallibility of the basis of the neoclassical economist.

My only response to economists these days: show me your experimental data.

It’s quite a funny exchange; from the commenters and the post author we hear plenty about axioms, utility, the sloppiness of Samuelson, etc. The level of the discussion reminds me of high school arguments where the smart kids didn’t show up.

For the record, I have used utility and marginal utility for estimating performance of systems that have nothing to do with economics. The theoretical results correlated well with experimental results. Or may be I was sloppy.

Good input. Not. Essentially amounted to ‘I’m smarter than you childishness’. No coincidence you mentioned high school.

“The theoretical results correlated well with experimental results. Or may be I was sloppy.”

Yes, you were probably sloppy in your experimental data and probably massaged it to fit. This guy sums up the intellectual crimes committed by the people you refer to as the ‘smart kids’:

http://www.google.ie/url?sa=t&source=web&cd=2&ved=0CCUQFjAB&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.tcd.ie%2FEconomics%2FSER%2Fsql%2Fdownload.php%3Fkey%3D236&rct=j&q=econometrics%20massage%20data&ei=Xa-JTpCkLJOS0QXHxangDw&usg=AFQjCNG-K_dx-1phSZl_mgsg-OYnz3pr6A&cad=rja

“For example, econometrics is often characterised by data mining and a prioristic conclusions; researchers massage results so as to produce an outcome that accords with personal opinion. This means that the theory has not been tested and therefore has not been subjected to the falsification principle. Econometricians rarely try to find out if there is another fit to the data, “acting as if the data admitted only a unique inference”. This was described by Solow (Blaug, 1992), in discussing the significance of econometrics for economics as “the biggest sin of all”. In Kenen’s (Blaug, 1992) words “It is not enough to show that our favourite theory does as well as-or better than-some other theory when it comes to accounting retrospectively for the available evidence”. It is difficult to disagree with Mayer (Mayer, 1993), who reports that the practice of running 30 regressions and only publishing the one that confirms a hypothesis is widespread, when he concludes that “this shouldn’t be done in hard testing”.”

Econometricians themselves — when they are honest and self-critical (many aren’t because they aren’t scientists) — often admit this. Bill Mitchell is always harping on about it and doing posts showing how certain economists massage data to ‘prove’ that certain policies work or don’t work.

Great post and fascinating exchange.

Samuelson’s non-sense is evident in his claim that utility is a “scientific construct.” Where is the data to affirm his claim that consumers really have fixed preferences that lead to maximum satisfaction? No human I’ve ever met conforms to this economic phantom.

The National Institute of Health (NIH) announced that they were going to start using economists instead of rats in their experiments. Naturally, the American Agricultural Economics Association was outraged and filed suit, but NIH presented some compelling reasons for the switch:

1) NIH lab assistants become very attached to their rats. This emotional involvement was interfering with the research being conducted. No such attachment could form for an economist.

2) Economists breed faster.

3) Economists are much cheaper to care for and PETA won’t object regardless of the experiment.

4) There are some things even rats won’t do.

However, it is difficult to extrapolate test results to human beings.

That’s the funniest post I have read in a long time. Thank you for bringing some levity to the unleavened discourse of economics.

Perhaps the first experiment should be to put economists in a Panopticon and see if they “reform” their behavior. Who could stomach watching them endlessly though?

All you need to know about utility is

1) that maximising it based even on the consumption of a small range of good: as little as 10, is too complex and time consuming to do.

2) People demonstrably don’t maximise utility when faced with making choices between a range of commodities.

3) There is no way of aggregating individual utility maximising decisions to a market demand curve.

Point 3) means that it remains in the realms of psychology rather than becoming an economic concept. The extent to which it is useful psychology is another matter.

Interesting post. If people are rational shoppers, then the gigantic amounts of money spent on advertising and marketing are a waste. I think people often are rational, but simply not interested in comparison shopping; and they maximize their pleasure by not thinking about the pros and cons of — say — different health insurance programs or different hospitals. A lot of buying is done because it’s convenient — the close store, rather than the more distant store; because you’re bummed out and want the lift that come from spending money; because you’re angry at having to be careful with money; because you are made anxious by what you will have to learn to make a rational choice — this brings us back to health plans; because an ad had told you that this object will make you happy; because you don’t have the time to make a careful decision… And on and on… All these can be rational decisions that maximize pleasure, but they do not lead to prudent buying.

Eleanor,

Excellent points and they remind me of a joke I heard back in the 90’s.

Two Russian mobsters are at a night club chatting and then they both realize that they are both wearing identical Armani suites. One says to the other, “I paid five thousand dollars for this suite”. The second mobster says “Hah. I paid seven thousand dollars for MY suite”. A third person nearby overhearing the conversation says to her friend, “see

Natasha, with good marketing you can get almost anyone to believe anything, want anything and pay whatever price”.

OK, joke on me, I meant suits not suites. Been thinking too much about some upcoming hotel reservations.

A lot of buying is done because it’s convenient — the close store, rather than the more distant store; because you’re bummed out and want the lift that come from spending money; because you’re angry at having to be careful with money; because you are made anxious by what you will have to learn to make a rational choice — this brings us back to health plans; because an ad had told you that this object will make you happy; because you don’t have the time to make a careful decision… And on and on…

Eleanor, I think you’ve hit on something really important here. Samuelson imagines a perfect consumer; someone who reacts in a completely appropriate manner to price signals and doesn’t buy anything without reading the most recent “Consumer Reports” article on such objects, thus maximising his/her satisfaction in terms of features, price, quality, durability, etc. This is probably a useful theoretical construct, but it breaks down badly in the real world as it runs into actual people. (Note that signals about “features,” “quality,” and “durability” are not the same as signals about price, but they do relate to the ideal of a “perfect consumer.”)

Now let’s go a step further and imagine that everyone is a “perfect consumer.” This is probably still a marginally useful construct. However, when we get to the real world, consumers receive signals about many, many more issues than price, which is where Eleanor’s post comes in – she identifies the important issue of noise, which frequently overwhelms the other signals.