By Thomas Ferguson, Professor of Political Science at the University of Massachusetts, Boston, Paul Jorgensen,s Assistant Professor of Political Science at University of Texas and Jie Chen, University Statistician at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. Cross posted from Alternet

Analysts of American elections routinely confuse the voice of the people with the sound of money talking. Habitual modes of thought and long standing incentives to reaffirm the democratic faith encourage grasping at straws. Pundits become hopeful that big money doesn’t matter as much as they feared, and that democracy is alive and well.

In the Spring of 2012, however, as Mitt Romney’s Super Pacs carpet bombed the rest of the Republican field into oblivion, falling into that trap became much harder. It was obvious that a handful of multimillionaires were playing pivotal roles in the election. Despite some talk about small donors in President Obama’s campaign, the general election enhanced the impression that American politics was sliding into a new and sinister phase. Once Romney clinched the nomination, his campaign paused to restock its war chest in advance of the Republican convention. The Obama campaign seized the opening. Instead of waiting until fall to deploy its heavy artillery, first the president’s formal campaign vehicle and then its nominally independent SuperPac laid down monster barrages of negative ads.

Sheldon Adelson, Harold Simmons, the Kochs, and a raft of Wall Street 1 percenters responded by opening their wallets even wider to the GOP, determined to engineer their own vision of “real change.” As campaign expenditures soared past all records, unpublished polls showed voters of all persuasions – even many Republicans – filled with revulsion at the spectacle of elections so clearly compromised.

Alas, in America, it’s tough to keep a bad idea down. Only hours after polls closed on Election Day, a revisionist wave began building that downplayed the role of big money. Analysts asked if the costly Republican failure to retake the White House and a handful of Senate reverses meant that all the handwringing about the torrent of political money was misplaced:

Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney was supported by outside groups that outspent allies of President Barack Obama by $260 million. And yet he still lost. This ultimately raises the question of whether the much-feared independent spending unleashed by the Supreme Court's 2010 Citizens United ruling was a dud. After all that money spent by independent groups largely financed by billionaires and millionaires, the government looks almost identical to the way it did before. Obama remains president, the Senate is firmly Democratic and the Republicans control the House.” (Paul Blumenthal, Huffington Post).

The skepticism quickly hardened into conventional wisdom. Even the Sunlight Foundation, which, along with the Center for Responsible Politics, has probably done as much as any institution to deepen awareness of how money corrupts American democracy, joined the parade. Its assessment of “How Much Did Money Really Matter in 2012?” investigated the emerging post-campaign narratives according to which all the outside money (more than $1.3 billion) that poured into the 2012 election didn’t buy much in the way of victories.” Its conclusion was that the story holds up: we can find no statistically observable relationship between the outside spending and the likelihood of victory.

Here we choose our words carefully. It is impossible to assess precisely the totality of money’s influence on the 2012 elections, but notions that it did not matter can be immediately dismissed. The evidence we have reviewed suggests exactly the opposite: that most of 2012’s little piggies went to market.

Let’s take the House elections first. If you want to understand money’s role in an election, the best idea is always to try the simplest approach first. Recognize that candidates and Super Pacs coordinate, whatever the law. Thus, don’t try too hard to artificially separate “outside” from “inside” spending, where the latter refers simply to expenditures by candidates’ formal campaign committees. Instead look at total spending by or on behalf of candidates and then ascertain whether relative, not absolute, differences in total outlays are related to vote differentials.

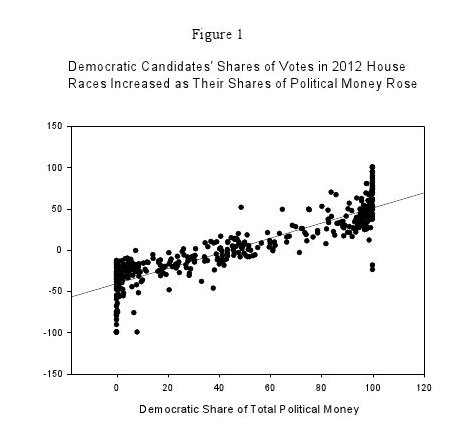

In 2012, across the House as a whole, they certainly were. As Figure 1 shows, a virtual straight line relationship existed between Democratic candidates’ shares of total political money and their showing against their Republican opponents. (Our figure reflects formal campaign expenditures and cash hoards through October 17, plus Super Pac and independent expenditures reported as of Nov. 9. We exclude a handful of races in which candidates in the same party competed with one another. A very few races in which the FEC data are likely incomplete are included. None of these fine points matter.)

We would be the first to caution against rushing to the judgment that this striking figure is the whole picture. The relationship between levels of money and winning is for sure at least partly reciprocal (“endogenous” in social science jargon). For example, it is obvious that many donors will hesitate to pour money into races in which there is little chance of success. The same probably is not true of likely winners or, as we will see below, candidates running unopposed – analysts need to recognize auctions when they see them and not blithely assume that most money rains down on toss up races. Lots of other, unmeasured influences could also be at work, such as individual representatives’ committee slots, seniority, or his or her status within the national party and House leadership.

There is also gerrymandering to consider, though most discussions of that phenomenon in 2012 exaggerate its importance by failing to recognize that Democratic votes tend to clump more tightly in specific areas, thus confusing simple votes/seats calculations.

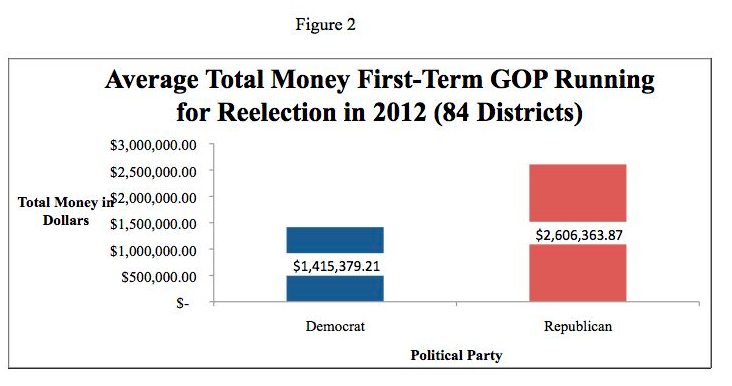

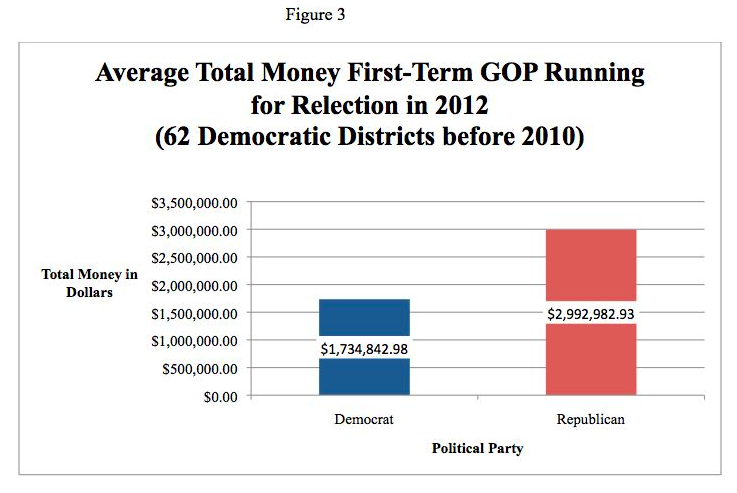

Other ways of breaking down the data confirm the impression that money was important. We are dubious about popular lists of “close elections”; we suspect many are affected by reports of campaign contributions. But we did examine spending differences between Democrats and Republicans in two types of races that should have had better than average chances of being winnable by both parties in 2012. The first involves districts in which a new Republican candidate won for the first time in the 2010 landslide; the other is the smaller subset of those races in which the GOP winner either ousted an incumbent Democrat or defeated a Democrat running in an “open seat” race. Both kinds of districts show heavy Republican advantages in average total spending compared to their Democratic opponents. (See Figures 2 and 3.) Walter Dean Burnham has impressed upon us 2012’s singular character in the long sweep of American history. Typically a party that takes losses on the scale the Democrats did in the House elections of 2010 bounces back fairly strongly in the next election. We think money goes a long way to explain why that didn’t happen this time.

A final piece of evidence about big money’s role in the House is also worth mentioning, especially considering the current furor over the fiscal cliff. GOP House Speaker John Boehner, running unopposed for reelection, raked in almost $21 million dollars in contributions to his campaign committee. (Our figures, like those above for the rest of Congress, do not include contributions to congressional leadership PACs, which we have not yet had time to examine. Boehner’s leadership PAC, though, took in just under $3.7 million dollars more. Boehner also has close ties to a Super Pac that received $2.5 million from Chevron late in the campaign.

The campaign committee of that other paladin of low taxes on the 1 percent, House Majority Leader Eric Cantor, took in some $7.6 million, with another $5.4 million going to his leadership PAC. By contrast, Nancy Pelosi, the Democratic minority leader, raised $2.3 million for her own campaign (less than what Chevron alone donated to the Boehner Super Pac) and slightly over $1.1 million for her leadership Pac.

What about the presidential race?

In sharp contrast to Mitt Romney, the President did not mock poor people. His campaign was not a cartoon of 1950s white America, nor was it flanked by aggressively garrulous billionaires. Early in the campaign, its fundraising even appeared to lag for a while among the 1 percent, though our impression is that those stories reflected confusion over how the White House was raising the money. The campaign also touted the number of small donations it was collecting, striving in 2012 to create the same impression that it had in 2008, that donors of modest means propelled it forward.

In the final weeks of the campaign, it looked as though the Romney campaign would hugely outspend it. Based on data for Super Pacs through roughly October 27, we raised the question whether the Romney campaign’s advantage in the final weeks might approach that of 2000, when George W. Bush’s campaign emulsified Al Gore in the battleground states.

A few days ago, however, the Federal Election Commission posted reports by both the Romney and Obama campaigns covering the final days of the campaign. Read in the light of reports by the Super Pacs, these lead to some surprising conclusions. Firstly, total spending by both campaigns, including the Super Pacs, was much closer than generally supposed, though the wide range of secondary committees that the campaigns utilized makes a single estimate treacherous and double counting an occupational hazard. One summary that (very reasonably) takes a wider view of total receipts than we do below suggests the Romney camp spent perhaps $1.51 billion, while Obama’s campaign just a shade less — $1.45 billion.

Secondly, in the last week of the campaign, contrary to what we feared at the time, 2012 was very far from repeating 2000 – though the Republicans spent more, spending by the Obama campaign also surged.

These numbers inevitably raise the question whether the Obama campaign’s 2012 claims to be fueled by small donations might be as hollow as its 2008 claims turned out to be.

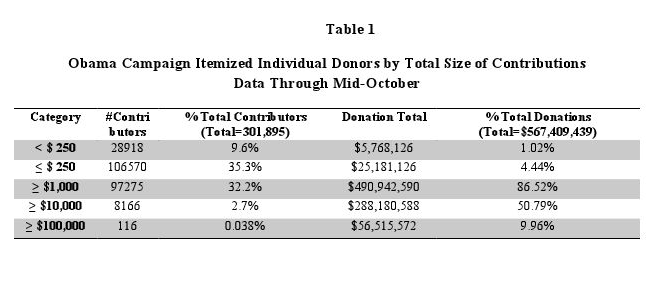

Though the FEC has posted summary reports for the campaigns, it has inexplicably not updated the roster of individual donors to the President’s campaign, even though campaigns file these reports electronically. But we can use the data that are on file, covering the period through mid-October, to make an estimate that past experience suggests will change only slightly.

Our figures reflect only the narrow list of campaign committees that concentrated on the President’s campaign. They include his principal campaign committee, the main Super Pac, a few much smaller Super Pacs that only gave to Obama, and the Democratic National Committee and some other committees that engaged in joint fundraising with the President’s campaign). We employ the same intensive name matching techniques that we used for our analysis of 2008 and have taken pains to eliminate double counting among committee transfers, so our totals, which are for individual contributions, will run lower than some published estimates.

Our results are extremely interesting. As Table 1 shows, across the entire roster of contributions reported to the FEC (i.e., those summing to $200 or more), contributions adding up to less than $250 supplied barely 1 percent of the campaign’s funds. Contributions below the threshold of $200 dollars don’t have to be itemized. Obama’s principle committee reported raising $234 million in unitemized contributions, while the Victory committees reported raising $94 million; it is likely that the real total is less than the sum of these because of double counting of committee transfers. By contrast, eighty-six percent of all the itemized money came from donations summing to $1000 or over, with over half of it coming from individuals donating $10,000 or more. (Because the unitemized totals come from later spending reports, it is senseless to compare them directly with the total for itemized contributions shown in our table – that number will rise sharply when the FEC finally posts the full roster.)

Our conclusion is that there is nothing paradoxical about the Republican loss. One campaign funded largely by the super-rich lost to another just about as affluently funded.

On another occasion we will pursue the question of what this might mean for the future. For now we remind readers that the dynamics of campaigns funded mostly by major investors are quite different than the campaigns imagined by traditional democratic theory: “Big Money’s most significant impact on politics is certainly not to deliver elections to the highest bidders. Instead it is to cement parties, candidates, and campaigns into the narrow range of issues that are acceptable to big donors. The basis of the “Golden Rule” in politics derives from the simple fact that running for major office in the U.S. is fabulously expensive. In the absence of large scale social movements, only political positions that can be financed can be presented to voters. On issues on which all major investors agree (think of the now famous 1 percent), no party competition at all takes place, even if everyone knows that heavy majorities of voters want something else.”.

So when Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner, who is now in charge of the talks on the fiscal cliff for the White House, tells reporters that the administration would like to include Social Security in the negotiations, pay attention.

Its a nice analysis, but I think a lot of it is beside the point. The data for campaign donations at the ELECTION stage is ambigous because I doubt in most presidential, as well as most congressional races, money makes that big a difference at the general ELECTION. The republicans chose the least insane candidate (I did not however say “not” insane) but it didn’t do them any good, and even much more money would not have gotten Romney elected president. But money got Romney the nomination (did money assure the least insane republican, or would not needing money so much have meant someone like Christe would have run and been successful in getting the nomination???)

Money does however determine what (who) will be on the buffet (at the primaries) and what your dinner (candidates) will be.

We get a choice of au gratin or scalloped potatos. No turnips, brocoli, or sushi, no pickled vegetables, no hamburgers, no pizza. You get potatos – you can have your potatos anyway you want them, and much sturm und drang goes into the selection of how to have your potatos…but its still potatos.

http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2012/12/why-america-cant-pass-gun-control/266417/

What is interesting to me in the article is how safe most seats in congress are. And in most districts the nominee for office will either ALWAYS be a democrat or it will ALWAYS be a republican. So to the extent their is any choice, it is in the primary election and prior to the general election. And considering how few people vote in primaries, and how little money it takes to set a primary candidate up as the nominee….its no surprise that we are having ….yup, potatos for dinner. But you can’t bitch about your dinner, because you do get to choose between mashed, fired, scalloped, or au gratin…potatos.

Money doesn’t matter so much in determining which candidate wins as it does in determining what the winner does after he wins. It seems to have cost $3 billion to finance a choice between two guys each of whom was dedicated to the cause of exactly the same people. Gosh, who could have imagined that?

Can I please have a list of those poor suckers who contributed less than $250 to either candidate? What were they thinking?

Thank you for the effort and analysis. As always, it’s sad that this type of actual insight remains absent/closed out of conventional wisdom/main stream journalism. And, that’s doubly so given that folks like Prof Ferguson and his colleagues routinely offer analytically grounded insight that MSM need only link to and build from. The point being that, yes, MSM are under financial pressure because of the breakdown in legacy biz models. But, here they have free content… it costs them nothing to use it.

I would add one more thought to this conversation: The rush to opine on conventional wisdom about the effectiveness of big money on buying an election has overlooked a major reality: people learn.

MSM may try to avoid being superficial.. but when MSM concludes in Olympian fashion that, hey, this shows/demonstrates/proves the limited effect of Citizens United, MSM betrays it’s evident inability to think beyond the all too short news cycle (which in web time is about one second).

People learn. Adelson, Kochs, others have already begun to learn; and they are paying professionals a lot of money to help them learn.

Odds are they will do a good job of learning — and 2014, 2016 and beyond will yield a huge return on their investment.

What is this, an attempt at incessant droning to break our resistance?

http://www.scribd.com/doc/33078217/The-Aristocracy-of-Monied-Corporations

Ignored in this analysis is a recognition of the myriad of ways the propaganda system defines and sets the parameters of legitimate discourse.

“Economics” as “science” in which all thought that bases itself upon factors that exist in the real world is dismissed as incompatible with mathematical rigor, and anyone attempting to challenge the mainstream is denied voice, tenure, and publication.

“News” as defined buy a handful of organizations owned and controlled by the ruling elite, and concerned only with short term maximization of advertising revenue.

“Think Tanks” funded by the ruling elite and designed to shape the parameters of legitimate thought.

“Education” in which the approved text books are published by corporations with a vested interest in maintaining their monopoly over ideas.

“Democratic Elections” organized as a circus in which meaningful debate is systematically avoided and the only choices are between competing flavors of policies favorable to the ruling elite.

“National Defense” in which an imperial army and the world’s largest military budget hides behind waves of fear and hate manufactured by a compliant media monopoly.

“Justice” in which the rule of law applies only to those who cannot afford to buy their exclusion from it by becoming “Too Big to Fail” or by raising money for political candidates (see John Corzine.)

I agree.

As human beings we create our own reality. What is the role of myth? We tell ourselves how things are, that things may be so.

At one point in our history, the myth of America as the Land of Opportunity helped it to be so. The myth encouraged people to take risks and grasp opportunities. Today, the same myth keeps America from being the land of opportunity. When people take risks and fail, blame is laid upon them instead of examining the forces arrayed against opportunity.

Now, the myth of American Democracy keeps us from seeing the ways in which and the degree to which we have become a plutocracy.

I think we should take the opposite tack. Why not accept that politicians are hugely influenced by campaign donations, then devise a system for each voter to donate money?

The real tragedy of our campaigns isn’t that our politicians can be bought, it’s that they can be bought so cheaply. The entire presidential race cost $3bil. If you add in another $3bil for all the rest of the federal races combined (just speculation; I’m not sure how much it actually cost), that’s $6bil to control the 538+1 people that are in charge of the $3tril pig trough known as our federal budget. (And that control lasts 2-4 years…) That return on investment blows away any other investment a person or corporation could make.

As long as that dynamic exists, it doesn’t matter what restrictions / regulations you place, people will find a way to buy the elections. IMHO, the only way to drive out corporate money is to make the return uneconomical, by flooding the election with people’s money. How? I’d propose that every 2 years, the federal government set aside $100 for each registered voter. $100 x 150mil registered voters = $15bil. Then, each voter could designate how he/she wishes that $100 to be spent. It could go to any candidate who qualifies for the ballot, not just the big 2. You can decide which races to spend on, and who to spend it on. If you’re a rabid Ron Paul fan (for example :-), you could spend all $100 on him. If you’re an independent undecided, you could throw $10 to a bunch of different candidates in different races. But you *must* spend the money. Whatever unspent money is left, the fed. govt divides and distributes based on the relative breakdown of contributions to each candidate. This way, the govt ensures that there will be $15bil of spending in the federal election. Any corporation that wishes to spend is free to donate as well, knowing full well that they will have to overcome a $15bil advantage before they see any real return on their investment (especially if their position is politically unpopular).

$15bil every 2 years is a pittance for the federal govt. and a small price for we the people to pay to ensure the federal budget reflects our priorities. And reducing a corporation’s ROI by 1,000% will lead to significantly less corporate money being spent.

Our Supreme Court has ruled that we can’t violate a corporation’s free speech. Fair enough. But the constitution doesn’t guarantee that that speech has to be as cheap as it is now.

“Why not accept that politicians are hugely influenced by campaign donations, then devise a system for each voter to donate money?”

Oh, great! One dollar, one vote. Way to disenfranchise ordinary people!

Sadly, it may be the only kind of proportional representation viable in the US.

OIC, you were proposing the public subsidy of elections. Whatever its merits, that’s not disenfranchising. Sorry.

What matters is not just whether money influences the vote, but whether politicians and party apparatchiks believe that it does (or at least whether they believe there is a reasonable chance that it can). That’s enough to make politicians and parties beg for bribes (oops, I mean tolerate independent expenditures).

Maybe a miracle will occur and the apologist commentariat will convince the pols that money doesn’t matter, and maybe today is the end of the world. Meanwhile the constant drone of rationalizations will convince many people, especially Serious Sophisticated People, that money doesn’t matter. Only children, and those who maintain some remnant of childlike independent thinking, will see that the emperor has no clothes.

San Francisco: The Al Bundy Economy

The only thing funnier than critters here lining up to buy the latest shoes off the boat is the attitude of the salesmen. It’s an Al Bundy fantasy. You can actually get laid here for selling shoes at 50X cost.

What that should tell you is that:

You can replace the empire with a program of any legal and accounting set that results in a distribution of delays, in a programmable positive feedback loop of positive feedback loops, and your costs will plummet, your control will increase, and your economic activity will skyrocket, because all the make workers – lawyers, accountants, CEOs, public administrators, etc. will be able to shop 24 hrs/day. Just assign them to work at home.

We can do things the easy way, or the hard way…

Analysts of American elections routinely confuse the voice of the people with the sound of money talking. Habitual modes of thought and long standing incentives to reaffirm the democratic faith encourage grasping at straws. Pundits become hopeful that big money doesn’t matter as much as they feared, and that democracy is alive and well.

A false assumption is made that the Pundits or “Analysts of American elections” give a shit. They don’t. Not only do they NOT give a shit, they take pride in not giving a shit. What they DO care about is to say what they are told to say and to say it convincingly so that the rubes buy it. They get extra points if the rubes think they’re clever, but most of the time, given the absurdity of the message, looking clever is pretty damn hard so ratings don’t really matter as much as the ability to keep a straight face. See Wolf Blitzer for an extreme example of where ratings mean nothing. If they did, he, Tweety Bird, and a host of others would have gone “poof” a long time ago and disappeared before our very eyes.

And after the last round of farcical comedy wherein pundits competed at saying things like, “elections” with a straight face, these tools were told to say, “Don’t worry your pretty little heads about how much is spent on elections. Money doesn’t matter, what matters is that your team wins”.

Of course, not even the village idiot, Joe Biden, is fooled for a minute. If money didn’t matter, why would the same people, the same corporations with armies of real analysts, spend more and more of it each election cycle?

Another way to look at it is to look at the money spent by the two main parties as money spent against any alternative party. So the two parties spent billions and combined got the kind of vote total that ruling parties got in elections in communist nations.

This expresses the essence of the post, but in an unclear manner, and, consequently, I am not sure I agree with it. For me at least, it would be clearer to say that a great deal of Big Money is spent to ensure that no matter what any candidate says or who is elected, a corporatist neoliberal, definitely kleptocratic, agenda will be pursued.

The atmospherics would vary according to which party won what but the core would be largely indistinguishable. This essential equivalence was captured in the references to Robama and Obomney. In this sense, it is irrelevant to look at Democrats success over Republicans or Republicans success over Democrats. The defining struggle of our times is not between them. It is between us in the 99% and the 1% who buy both sides in elections and own the electoral process.

The Obama campaign 2012 claims to be fueled by small donations? You mean the kind run through HSBC $9,999 at a time?

Look, they would never do that.