Yves here. This is an important post, in that it describes how the Fed, despite the unconventional look of some of its measures, is using more extreme variants of traditional policy approaches, and why that is not such a hot idea.

One place where I quibble with Alford is in attributing the way Greenspan dropped short term rates dramatically in the early 1990s recession as driven by unemployment policy. At the time, there was considerable concern about the health and stability of banks in the US. It wasn’t just savings and loans that were hemorrhaging losses. Citibank nearly went under. Some major commercial banks in Texas and the Southwest had lent heavily to spec commercial real estate projects at just the wrong time. And although it was mainly foreign banks that hoovered up participations in LBO financings, like Campeau, that came a cropper, US financial firms had exposures as well. Greenspan’s driving short term rates to the floor created an extremely large spread between short and long term interest rates, enabling wounded banks to borrow short and lend long, and rebuild their capital bases out of artificially high profits.

Another quibble is at the very end, where Alford is correctly concerned about our sustained trade deficits, but also is unduly exercised about our fiscal deficits. They are in fact necessary and desirable as long as the business sector keeps net saving, which it did even in the years immediately preceding the crisis. If capitalists refuse to play their proper role and loot rather than dedicate resources to future growth, government has to step in. But as we are seeing now, what is unsustainable about this arrangement is the politics much more than the economics.

By Richard Alford, a former New York Fed economist. Since then, he has worked in the financial industry as a trading floor economist and strategist on both the sell side and the buy side.

The FOMC under Bernanke is committed to purchasing $85 billion of long-dated Treasuries and MBS until such time as either of two unspecified thresholds is met, one for inflation and one for improvement in labor market conditions. Some FOMC members and others have voiced concerns and objections, but Bernanke has dismissed them. Promoters of the policy argue that the policy is unconventional and that it is a low risk adaptation to the current circumstances. However, recent economic/financial history suggests that policymakers are recycling policies that were discarded in the past, but most troubling is the total reliance on counter-cyclical policies to solve balance sheet and structural problems.

1970-1979

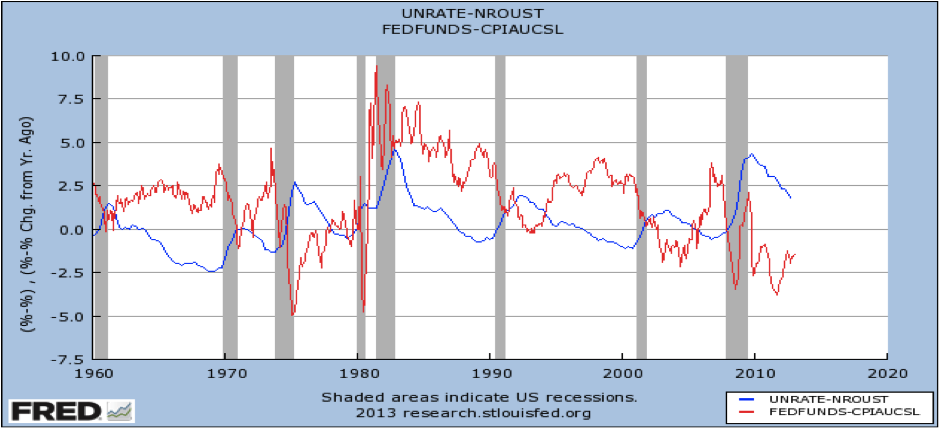

In the 1970s, with the costs of unemployment visible and the cost of inflation less so, US policymakers attempted to fine-tune US economic performance. Policy was aimed at increasing employment and output by exploiting a perceived stable trade-off between unemployment and inflation (Phillips Curve). However, long and variable lags and the fact that the trade-off between unemployment and inflation is not stable implied that whenever the Fed eased or tightened policy, it eased or tightened policy too much and for too long. As a result, policy was pro-cyclical, inflationary on balance and opaque as it was left to Fed watchers to divine changes in policy.

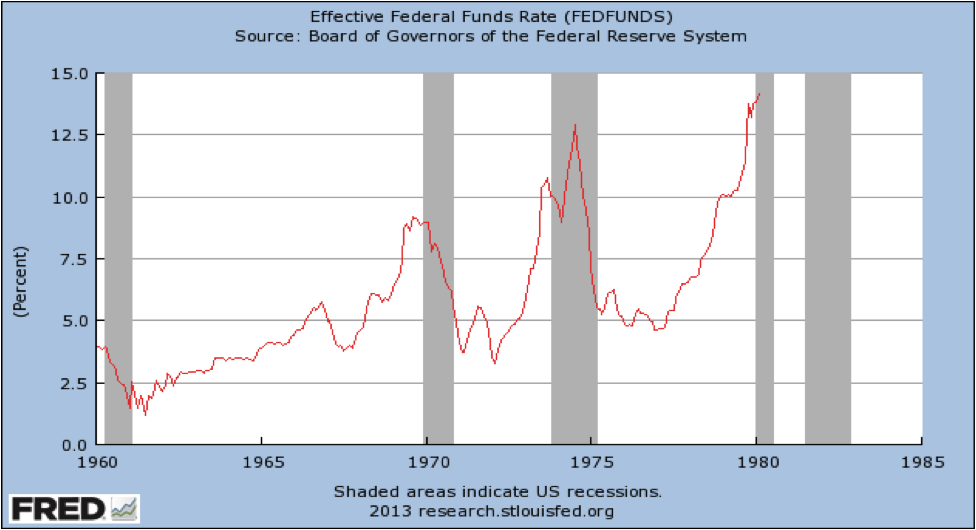

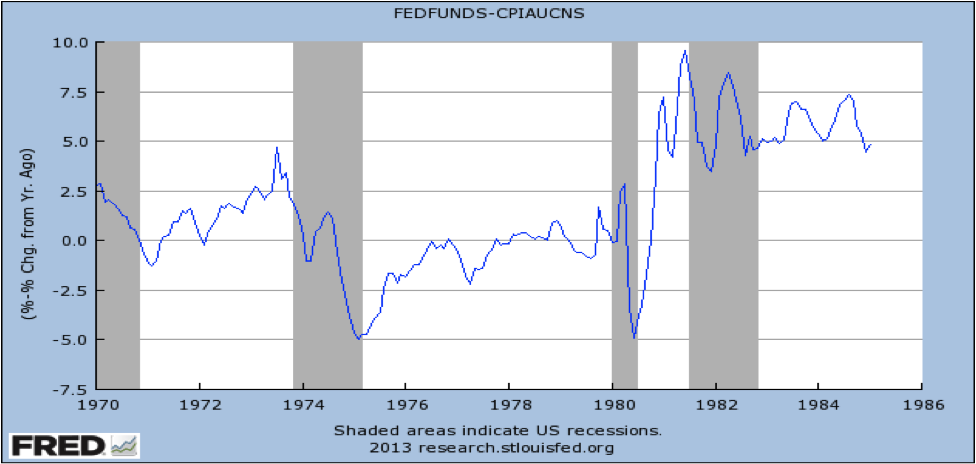

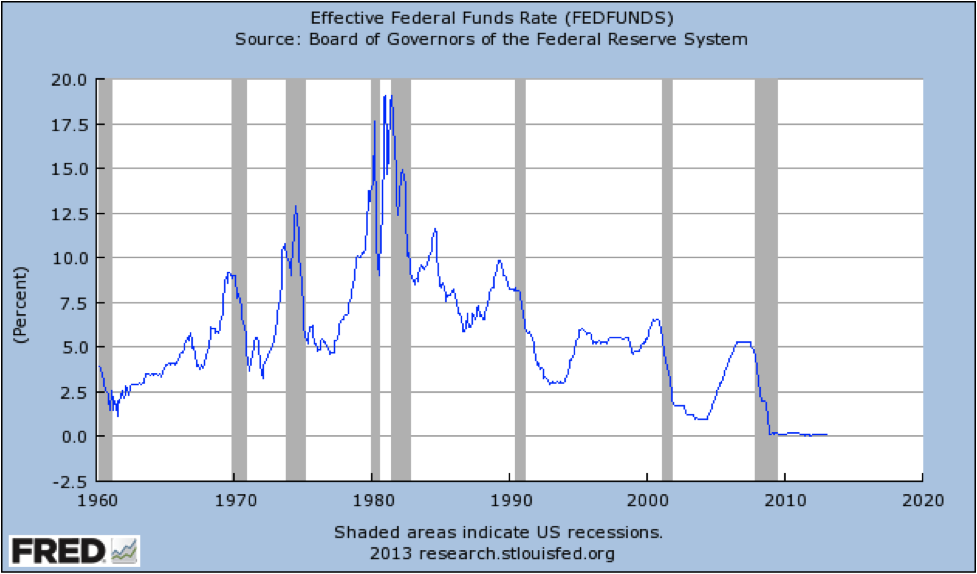

The chart above captures the too-much-too-long aspect of Fed policy prior to 1979. The peaks and troughs in the Fed funds rate (the Fed’s operating target) peaked close to or after economic cycle peaks in cases of tightening, and bottomed close to or after economic cycle troughs in cases when the Fed was easing. Given the lags in monetary policy, this implies that the FOMC over-tightened and over-eased. The Chart also reveals that the amplitude of the swings grew, with the each swing larger than the one before.

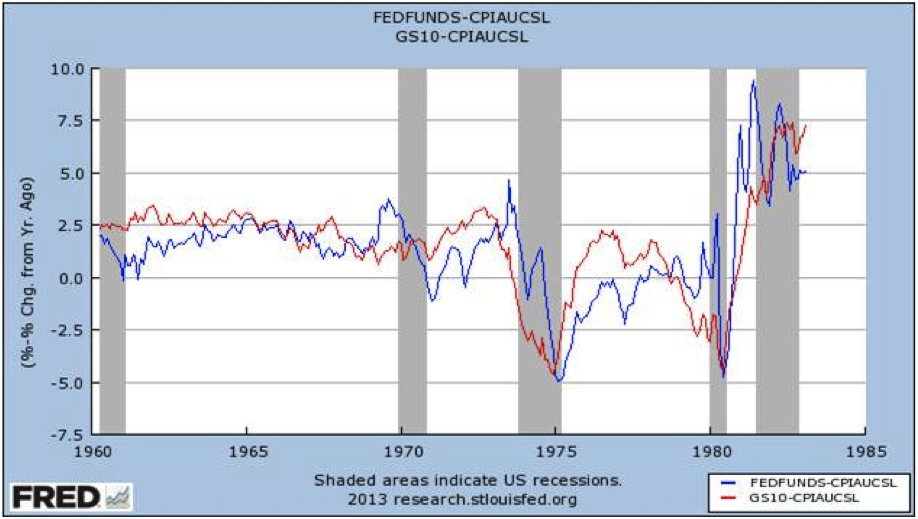

This pattern of progressively wider swings is also visible in the “real” Fed funds rate and the “real” 10- year Treasury yields.

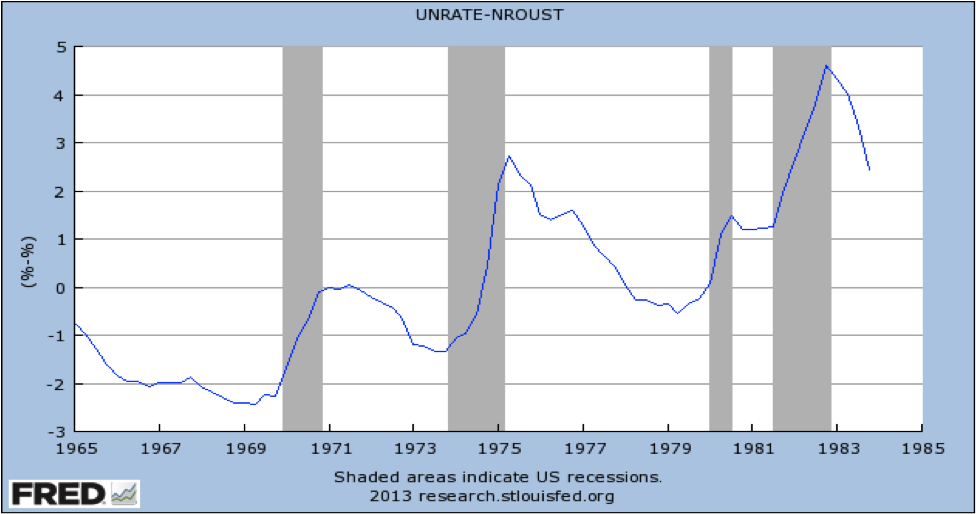

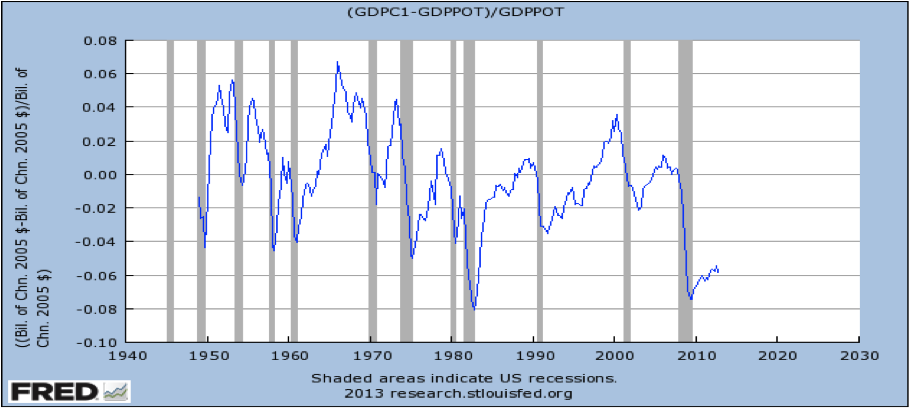

The cost of this policy mistake is also reflected in the larger swings in the difference between the unemployment rate and the CBO’s estimate of the short-term natural rate of employment (NAIRU). Furthermore, the cyclical lows in excess unemployment rate became progressively higher.

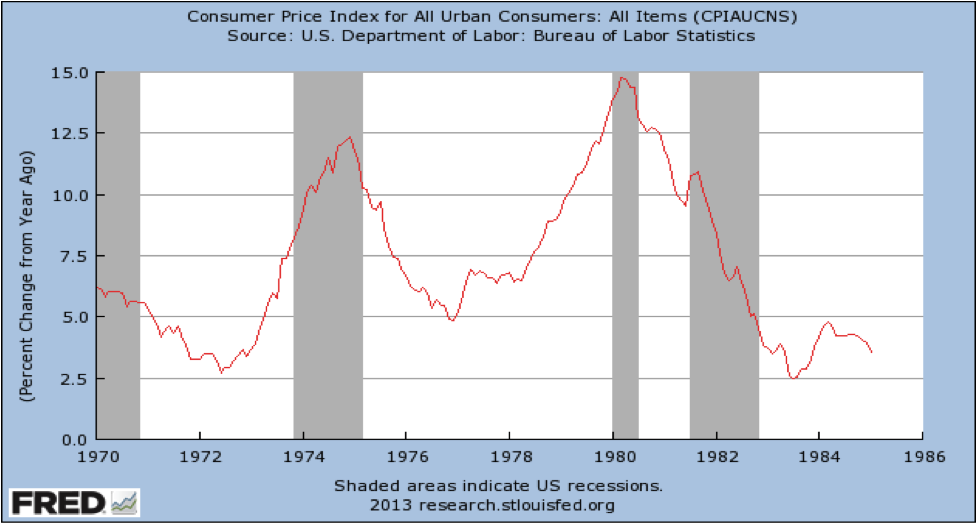

The inflation rate also ratcheted up over time.

The Policy Response 1979-1983

Both real economic performance and inflation were the impetus behind Volcker’s decision in late 1979 to introduce changes in the design and execution of monetary policy. The Fed adopted the targeting of monetary aggregates and changed operating procedures – targeting non-borrowed reserves instead of the Fed funds rate. The new targets and procedures are reflected in the behavior of the Fed funds rate, which became more volatile.

However, the frequency and amplitude of cycles in the real economy, as well as the inflation rate were reduced.

The adoption of non-borrowed reserve targeting, and the targeting of monetary aggregates reflected the increased importance attached to the size of the Fed balance sheet, an emphasis on the costs of inflation and a step back from attempts to fine-tune economic performance. In October of 1982, with inflation on the decline and financial innovation altering the relationship between the narrow monetary aggregates, economic performance and inflation, the Fed abandoned targeting non-borrowed reserves and again employed a Fed funds rate operating target. It also chose to target a broader measure of the money supply. Some observers criticized the Fed for not reducing the Fed funds rate more quickly. They cited the continuing high rate of unemployment and the fact that the real Fed Funds rate remained decidedly positive. It had been negative at cycle lows and for periods of time during the 1970s.

However, by mid-1984, the difference between the unemployment rate and the CBO’s estimate of the short-term natural rate of unemployment (NAIRU) was approximately the same as it was in the mid 1970s, at which time the inflation rate had been 10 percentage points higher. Furthermore, the rate of decline in the unemployment rate post the cycle trough in 1982 was more rapid on average than the decline post the cycle trough in 1975. Most important was the break from the pre-October 1979 pattern of progressively larger cyclical swings in unemployment rates from progressively higher cyclical troughs.

Policy Under Greenspan

Fed policy continued to change under Greenspan. Changes in the inflation rate, interest rates, and the financial environment complicated the use of monetary aggregates in the design of monetary policy. By 1993, the relationships between the monetary aggregates on the one hand, and inflation and output on the other had become so unpredictable that they could not serve as a guide to policy. The targeting of monetary aggregates was formally abandoned.

There were other changes under Greenspan. Monetary policy also came to reflect a less activist anti-inflationary stance than under Volcker. The Greenspan FOMC chose to pursue policies of “opportunistic disinflation”, i.e., not actively pursuing lower rates of inflation, but allowing shocks to reduce inflation. However, the Fed pursued activist discretionary policy in response to unemployment. This was reflected in the decline in the Fed funds rate by almost 7 percentage points from its cycle peak in the spring of 1989 to its trough (near zero in real terms) in 1993.

However, there are also indications that post-1993 the FOMC adopted the idea of avoiding the pro-cyclical policies of the 1970s, i.e., it would move sooner and by less. This may have played a role in the surprise shown by the market in response to the Fed’s first tightening move in February 1994. It may also be reflected in the Fed’s decisions to raise the Fed funds rate slowly, by roughly 25 bps per meeting, and to cease tightening below the previous cycle high despite the irrational exuberance in the stock market.

The Fed, however, became activist again on the downside after the tech bubble burst in 2000. The Fed dropped the funds rate from 6.25% to 1% in nominal terms. At the trough, it was decidedly negative (-2.5%) for the first time since the 1970s. After a year at 1%, the Fed began its program of tightening at a measured pace, increasing its target for the Fed funds rate by 25 bps per FOMC meeting despite warnings by many of a bubble in housing prices and increased risks in the financial markets.

Economists outside the Fed had also been revising their view of the best approach to macroeconomic policy, especially policy monetary. NAIRU had replaced the idea of a non-transitory tradeoff between unemployment and inflation. As a result, an inflation-only target for monetary policy became widely accepted. The policy failures of the 1970s also encouraged research in to replacing discretionary policy with a rules-based policy regime.

The Bernanke Fed

The FOMC continued tightening at a measure paced until the Fed funds rate peaked at 5.25% after Bernanke was named Chairman in 2006, but its approach to policy changed. Rules-based policy explicitly replaced the use of discretion as the basis for policy design. A Taylor Rule variant was explicitly accepted as a guide to policy. (Some analysts have argued that the Taylor Rule or variants thereof explain the behavior of the Fed funds rate going back at least as far as 1988.) This step was a rejection of discretion and forecast-based policy design. The end of discretion was expected by many economists to mitigate attempts at fine tuning. The Taylor Rule also employed directly observed and not estimated values for variables (at least large revisions to the PCE deflator necessitated the smoothing of the series). Inflation-only policy became associated with Taylor Rules that specified larger policy responses to deviations from the targeted inflation rate than from deviations from the output target.

As implemented by the Bernanke FOMC, the rules-based approach had corollaries: policy transparency and expectations management. Policy transparency had a number of dimensions:

1) publicly announced policy goals (for unemployment and inflation),

2) a publicly announced rule specifying the policy reactions to deviations from policy goals, and

3) verbal guidance on the pace of policy adjustments.

During the later years of Greenspan and the early years of Bernanke, policymakers were generally rather pleased with the performance of the economy and their contribution to that performance. They felt that they had successfully fine-tuned the economy and that a lasting Great Moderation was set in stone. While the economy did perform well in terms of inflation and unemployment, numerous economic and financial fragilities and unsustainabilities also developed. As a consequence, the achievements were short-lived and were followed by the Great Contraction.

Policy Since the Financial Crisis and Recession

Once recession and then the financial crisis hit, monetary policy changed yet again. The policy response followed a path laid out in earlier Bernanke speeches. It had been the Fed position that a Japan-like outcome-years of slow growth and elevated levels of unemployment- could be avoided even after a financial market crisis if the central bank aggressively cut interest rates. The Fed did cut rates aggressively in two steps. The first step took the Fed Funds rate from 5.25% to 2% (and approximately 0.0% real) in just 10 months. The second step, roughly coincident with the Lehman crisis, took the Fed funds rate from 2% to approximately 0% (and approximately -2% in real terms) in 4 months. However, while the recession is finally over (NBER), growth — especially job growth — has lagged. Since 2008, with growth lagging and the Fed funds rate constrained by the zero bound, it became impossible for the Fed to generate the Fed funds rate implied by the Taylor Rule. With the Fed funds rate already near zero, the FOMC followed Bernanke’s “playbook” and monetary policy became “unconventional”, i.e., with bouts of credit and quantitative easing.

Old Wine in New Bottles?

While the policy employed since the Lehman crisis has been deemed unconventional, some new aspects of the current policy regime are surprisingly similar to aspects of policy regimes that were found wanting in the recent past.

Today, monetary policy is far from transparent. While the policy goals for inflation and unemployment where once public knowledge, policy is now contingent on an unspecified threshold level for inflation and on unspecified improvements in unspecified labor market conditions. The policy response once the thresholds are reached is also unspecified. In terms of transparency, we are back to the policy regimes of the 1970s-1990s.

Discretion in policymaking has also made a comeback. Rules-based policy has at least temporarily entered the dustbin of history. The Fed has not indicated how it will adjust policy should either of the unspecified thresholds be reached. It has not presented its exit strategy, i.e., when, under what conditions or how quickly the recent rapid growth in its balance sheet will be unwound or neutralized.

QE represents a return to the policy regime of non-borrowed reserve targeting introduced and then abandoned by Volcker. Both regimes used control of the growth of the asset side of the Fed balance sheet to influence interest rates, the real economy and inflation. Non-borrowed reserve targeting was dropped in favor of a Fed funds rate target, because the links between changes in the Fed balance sheet and economic performance were not well behaved. Today, with the economy in a liquidity trap, and the financial system still not performing as usual role, Fed policymakers are targeting balance sheet quantities again. It is unclear on what basis – in the absence of any “rule” — the Fed committed itself to purchase $85 billion of long dated assets per month or exactly what economic impact it expects. If the transmission mechanism was too uncertain in 1983 to allow for balance sheet quantity-driven monetary policy, how can the Fed commit to a specified rate of asset purchases now?

Given the uncertain relationship between the unspecified thresholds for labor market conditions and inflation and the unspecified exit strategy on the one hand, and full employment, inflation and economic/financial sustainability on the other, the Fed commitment to purchase of long-dated assets raises the possibility of the Fed once again doing too much for too long. It is widely acknowledged that the unwind of the run-up in the Fed balance sheet will be difficult and gradual. Given the lags in monetary policy, is the Fed planning on reversing policy before full employment is reached? Will it pursue stimulative policies until full employment is reached and worry about possible negative side effects later? Any exit strategy will be fraught with financial, economic political uncertainties and risks. Hence the commitment, itself, is fraught with uncertainty and risks. For example, research by members of the FOMC, private economists as well as economists at the BIS and IMF have found that that monetary policy can affect financial stability. Nonetheless, the FOMC has committed itself to ignoring financial market developments at least until such time as the unspecified thresholds are reached. The Fed has also chosen to ignore other developments including unsustainable patterns of aggregate demand.

But Have We Seen It All Before?

For all their differences in perspective and emphasis, most of the opposing evaluations of the merits of Fed policy have one element in common: They all appear to be largely prisoners of a Phillips Curve mentality. Policy is set based only on the current levels of unemployment and inflation. Policymakers, economists and pundits do not look beyond near-term changes in unemployment and inflation when evaluate the risks and returns of alternative policy responses.

However, there may be a more troublesome risk attached to current monetary policy. The risk is that the current policy stance – low interest rates as well as QE- is reducing the probability of a return to self–sustaining economic growth and contributing to a Japan-like outcome for the US.

For a return to full employment to be more than transitory, it must be supported by a sustainable pattern of demand. The pattern of demand was not sustainable in the mid-2000s. Consumption demand relative to income was too high and savings too low especially given the aging population. Investment in residential real estate investment was too high relative to income. The trade deficit was unsustainable and the Federal government was running a chronic fiscal deficit.

Monetary policy is currently promoting growth in employment and output, but the pattern of demand remains unsustainable. The financial repression dimensions of monetary policy have and will promote consumption and discouraging savings by the household sector, despite the fact that consumption remains unsustainably high and savings too low relative to GDP. Growth again is dependent on a wealth effect increase in consumption and a recovery in residential real estate investment. The fiscal deficit as a fraction of GDP is unsustainable high. The trade deficit remains unsustainable high and implies that the US is dis-saving as a society.

When monetary policy stimulus is reduced, consumption expenditures as a percentage of GDP (now approximately 70% of GDP) would tend to fall back to a more normal and sustainable level relative to income. If this were to occur at the same time the unsustainable fiscal deficit is being reduced, roughly 90% of aggregate demand would exert downward pressure on GDP. It is highly improbable that the remaining 10% of aggregate demand would grow fast enough to stabilize demand and output. GDP would fall and the economy would require the stimulus be replaced to achieve full employment, but the pattern of demand would again be unsustainable.

Is it possible that consumption could grow counter-cyclically cushioning the decline in GDP stemming from the withdrawal of policy support? Yes, but it would require that households were willing to reduce their savings rate out of current income. It has happened. The recession post-WWII was shallow and brief despite a decline in GDP driven by the fiscal retrenchment as the war effort wound down. Consumption demand behaved in a counter-cyclical fashion as an elevated savings rate declined as households satisfied pent-up demand created by war time rationing.

Unfortunately, the current circumstances, the savings rate and the composition of assets on the household sector’s balance sheet suggest that the response of consumption would be pro-cyclical, as it was in 2008. The savings rate remains well below historical norms. While the net worth of households is almost to the previous peak reached in 2007, the rebound has been driven by recoveries in the values of stock holdings and residential real estate.

Given the decline in consumption relative to disposable income during the past recession and the increased risk attached to borrowing against assets that can drop in value, it seems unlikely that households would finance increases in consumption relative to GDP by borrow against unrealized capitals gains on residential real estate and equity holdings when GDP is falling.

To allow for a self-sustaining recovery, policy should encourage households to rebuild the asset side of their balance sheets with safe and liquid assets. However, the current monetary policy stance discourages savings. It also discourages holding safe and liquid instruments as it encourages the private sector to move out the yield curve and invest in riskier classes of asset that are likely to behave pro-cyclically and contribute to pro-cyclical behavior in consumption expenditures.

There are risks associated with the current monetary policy stance and honest people can disagree about the right course. However, committing to a policy course and ignoring all developments other than the behavior of inflation and labor conditions beyond unspecified thresholds reflects a failure to incorporate any measure of risk control. Policy is not transparent. Elected officials, the markets and society are denied the ability to determine if policy is having the expected effects. This is inappropriate for a public institution like the Fed. Most troubling is the “sale” of stimulus-only policy as the means to return to stable growth with full employment. A self-sustaining recovery will also require efforts to rebuild balance sheets and rebalance the pattern of demand domestically and internationally.

“”While the net worth of households is almost to the previous peak reached in 2007, the rebound has been driven by recoveries in the values of stock holdings and residential real estate.””

I think it’s important to emphasize the difference between the productive sector and the FIRE sector. Amazingly, as pointed out in Michael Hudson’s ‘Beyond the Bubble’

“”Industry and agriculture, transport and power, and similar production and consumption expenditure account for less than 0.1 percent of the economy’s flow of payments. The vast majority of transactions passing through the New York Clearing House and Fedwire are for stocks, bonds, packaged bank loans, options, derivatives, and foreign-currency transactions. The entire stock-market value of many high-flying companies now changes hands in a single day, and the average holding time for currency trades has shrunk to just a few minutes.””

i think a tax on these transactions would help stabilize these volumes which are clearly speculative in nature.

This post is best read together with the ‘culture’ post – each point to determinedly closed minds among those economists like Bernanke who cannot for the life of them get outside very very narrow boxed thinking.

And as astute as Alford’s critique is, he nonetheless still gives B et al too much credit. Yes, ‘unstated’ inflation and labor thresholds are ‘stated’ objectives. ‘Stated’ objectives, though, are not the actual objectives. Indeed, Alford’s critique makes minced meat of these as actual objectives.

The actual objectives of QE and the rest are ‘extend and pretend’ — save the banks, save the banksters, save the career prospects of financial regulators, save the rivers of cash flowing from financiers et al to elected officials. This theory lies in idealistic yet empirically absurd notions that banks lend into the real economy. Absurd. Indeed, there’s an inverse relationship between the broad flow of cash to banksters and politicians versus the flow of cash from the financial sector into the real economy.

This is all about extending asset inflation until such time as bank balance sheets are no longer toxic (and all the poison has shifted to taxpayers – who, though, will be fine according to the theory because asset markets will be riding so high).

Equally unmentioned in Alford’s critique is this: the only way to find a path back to sustainable growth in consumer demand lies in shifting policy from promoting “an asset-based economy’ to ‘a jobs-and-salary/wages-based economy”. Bankers — along with the 1% and corporates — have zero interest or concern along those lines.

The old wine in new bottles, then, includes finding another way to strip mine consumers through flim-flamming them into further debt that, in turn, can heat up the asset markets needed to help the banksters start the ‘rinse repeat’ cycle all over again.

And look, another British songbird is ‘philling’ the air, Blanchflower, perhaps suggestive of Bush’s nickname for Rove ?

http://market-ticker.org/akcs-www?post=219356

What to say ? Perhaps this quote from Mike Lofgren, “A politician is a hog that is grateful to whoever is rattling the stick inside the swill bucket.” p.203 The Party is Over

or perhaps,

“Washington [London] is a company town just as Homestead, Pennsylvania, was in the days of Andrew Carnegie, but in this case the company’s products are politics and military hardware [BS financialization]. In a company town, everybody knows everybody else’s business [Anglophile spyalliance-junkies].”

Market Signals [or the strong bouquet of Denial]

“If you look at long-term bond rates or inflation expectations or any of the things that the market would use to signal that it’s worried, you really don’t see it,” Thoma said. “They can back off of this if they need without any kind of catastrophic collapse that he’s talking about.”

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2013-04-02/stockman-sundown-belied-by-stocks-showing-morning-for-investors.html

Cliff Notes Version:

“For all their differences in perspective and emphasis, most of the opposing evaluations of the merits of Fed policy have one element in common: They all appear to be largely prisoners of a Phillips Curve mentality. Policy is set based only on the current levels of unemployment and inflation. Policymakers, economists and pundits do not look beyond near-term changes in unemployment and inflation when evaluate the risks and returns of alternative policy responses. ”

[Inflation does not create our yobs.]

“For a return to full employment to be more than transitory, it must be supported by a sustainable pattern of demand. The pattern of demand was not sustainable in the mid-2000s. Consumption demand relative to income was too high and savings too low especially given the aging population. Investment in residential real estate investment was too high relative to income. The trade deficit was unsustainable and the Federal government was running a chronic fiscal deficit. ”

[Oopsie. But let’s assume the Fed can fix this?]

“To allow for a self-sustaining recovery, policy should encourage households to rebuild the asset side of their balance sheets with safe and liquid assets. However, the current monetary policy stance discourages savings. It also discourages holding safe and liquid instruments as it encourages the private sector to move out the yield curve and invest in riskier classes of asset that are likely to behave pro-cyclically and contribute to pro-cyclical behavior in consumption expenditures.”

[Of course the Fed can fix it. We are no longer consumers. We are “bagholders” in illiquid, risky and overpriced investments. Check with your financial planner and see if this country is right for you.]

I didn’t follow the article. But I’ve been complaining about the 6% solution whereby if we keep unemployment at 6% it will automatically control inflation. And the deception that the Fed can control full employment. The 6% solution is like saying, OK whoever is lucky enough to make it inside the gate before it shuts is going to prosper and the rest can crawl off and die. And the pretense that the Fed can control full employment is true only insofar as it can prevent it. And now the chaos we see within our own economy is not, as we are led to believe, of our own making. It is the result of a century of power plays to control what the rest of the world does. But we have neglected to control what we do. We got what we wished for. The solution does not fall under the aegis of the “Fed”; it is fully under the control of Congress. God help us all.

“The 6% solution is like saying, OK whoever is lucky enough to make it inside the gate before it shuts is going to prosper and the rest can crawl off and die.”

You live a very sheltered life. In many parts of the world, if someone does get decent professional job, they are left to crawl off and die, particularly if they are forced to live in urban areas, where traditional farming is not an option for self sufficiency. The situation is that no civilization can give everyone a decent life. Civilization, and urbanization were, historically, the products of aggression and the need to control and dominate (other people nature), NOT about freedom, or material happiness for everyone. In every civilization, there was always a small minority who lived very well, a small middle class, and a large number of disposable slaves at the bottom.

@Yves Smith sez:

Here’s another one: @Richard Alford sez:

But Have We Seen It All Before?

Obviously Alford is a very bright guy and he’s paid his dues within the money management ‘racket’. Yves = ditto. She’s hyper-intelligent and committed, otherwise I wouldn’t waste my time coming over here.

Nevertheless, I can’t either one of them seriously. What does ‘sustainable’ mean? More tract houses? More freeway lane miles? More auto sales? More F-35 fighter jets? More coal mines, gas pipelines, VLCCs … how about more airports? What is sustainable about any of this? How about those tens- of thousands of tombstone-like concrete towers in China? How many more vacant apartments are needed before the country gets to sustainability heaven?

How does everyone get there? There are seven billion of us hairless monkeys right now and only 15% have automobiles. Do we ‘arrive’ when 30% become automotive? Where do we put the 800 million extra cars? Where do we get the fuel for them? Does the US build another 55,000 mile interstate highway system to go along with the 55,000 mile system we already have? We cannot afford to fix our roads now! How is ‘more’ sustainable again?

This is gross abuse of the language. In order to ‘have’ our desired industrial goodies we must borrow. Our machines do not pay their own way. If they did there would be no debts as deploying machines would retire them. That they do not do so is self-evident. With thousands of millions of machines there is an exponential increase in debt required to assemble them and provide them with fuel. This is debt that even the entire world’s bloated finance establishment cannot provide.

Credit is a resource, too! It’s a means to allocate resources: with less resources to allocate, adding credit becomes pointless … and unaffordable. This shows up very clearly on Mr. Alford’s charts. Most of the recessions from 1970- onward were the result of fuel shortages- and price shocks. Even the modest credit demands of the time during periods of high fuel prices … were breaking.

Let’s be clear about something, children: the glory days of Joe Hill and the Noble Working Stiff and his overalls, lunch pail and Ford Galaxy 500 down at the union hiring hall punching in that $35/hr factory job are never coming back, ever! Santa Claus is not coming down the chimney with some glamorous industry or other to take the human race in hand and lead it into the Promised Land. Our collective future is binary: we are either joint-and severally ruined … or we escape ruin by the skin on our noses.

What do you think the plutocrats are doing right now? They know what’s going on because they can afford ‘intelligence’ and have the wiles to take advantage! They use the time remaining … to ‘loot’, then leave the rest of us to Mad Max.

It will take every single inner resource the human race possesses … clarity, honor, courage, perseverance, helpfulness, strength, wisdom … the willingness to endure tremendous suffering and hardship for decades and perhaps centuries … what is absent in popular culture particularly among finance analysts … it will take all of these things and more to escape our self-constructed annihilation.

Right now, this ain’t happening. Too much fantasy thinking/denial about redistribution … redistribute what, exactly? Deck chairs on the Titanic?

If we aren’t careful we will go extinct. This is not a game any more.

Two words: Peak oil.

Futhermore: The rise in oil prices and the prices of other commodities since China, India, Brazil, and other countries around the world began to join an integrated economy that spans the entire globe was not due to boogeymen investors speculating, it has been due to a considerable increase in human consumption of natural resources. Population has also increased since many countries around the world began to join an integrated global economy. All of this consumption has increased demand faster for natural resources faster than they can be provided.

Our problems are twofold: there is capitalism that encourages competition and concentration for resources. There is also the problem of people across the political spectrum feeling entitled to have as many children or consume as much as possible because of traditional values or because they have bought into the idea of utopian Progress; the institutions of modern industrial society: banks or government should satisfy their deepest wishes and desires while offering to do little to make those wishes and desires a reality besides sending their sons off to the occasional war for oil.