Yves here. I’ve sympathetic with the aspirations expressed in Boyce’s piece, but if anything, the measurement fetish is going in the other direction. Both businessmen and economists are obsessed with quantification, which leads to thing that are readily measurable, like transaction data, being assigned more significance than qualitative or hard to gather information. It also leads to data which is developed and derived (think GDP) being treated as being as “solid” because it is expressed as as a single figure, as a data point that is precise, such as the closing price of XYZ Widget’s stock on a particular day (see longer form discussion here).

Boyce also discusses other distortions in measures of growth that don’t get sufficient attention, such as the rising prices of positional goods. And rising income disparity makes societies less happy and less healthy, yet it’s become a cause for concern in the economic literature mainly because it is seen as a probably culprit in flagging growth rates.

By James Boyce, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and co-founder of Econ4: Economics for People, the Planet, and the Future. His most recent book is Economics, the Environment and Our Common Wealth. Cross posted from Triple Crisis.

Average national income is a notoriously imperfect measure of the average person’s well-being. The 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico – with clean-up and damage costs of $90 billion – added about $300 to the average American’s “income.” But it added nothing to our well-being. The world’s most expensive prison system, costing almost $40 billion per year, adds another $125 per person. This doesn’t make us better-off than people living in countries that don’t incarcerate one in every 100 adults.

Of course, national income includes many good things, too. Growing food and building homes add to national income. So does public spending on education and health care. Unlike oil spills and jails, these really do add to our well-being.

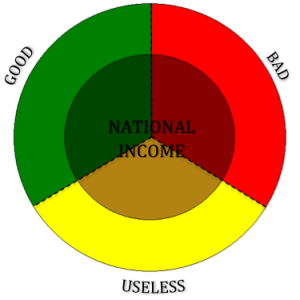

National Income: The Good, the Bad, and the Useless

Along with good stuff and bad stuff, national income includes a third category of stuff that’s just useless – goods and services that neither add to our well-being nor subtract from it, but still get counted in the income pie. A prime example is what the economist Thorstein Veblen called “conspicuous consumption” – items consumed not for their intrinsic worth, but simply to impress other people and jockey for a higher rung on society’s pecking order. These goods and services have zero net effect on national well-being, since for every person who climbs a rung, someone else slips one.

Of course, not all bad or useless things are counted as national income. But neither are all good things. Unpaid work caring for children, the elderly and the disabled doesn’t count. Clean air, clean water and climate stability don’t count. Open-source information and culture don’t count.

The national income pie is an odd subset of the good, the bad, and the useless. All three slices get lumped together when economists tell us that average income in the United States today is roughly $42,000 per person.

Researchers in the emerging field of happiness studies have devised other ways to measure well-being. They find that beyond the level of income that is needed to satisfy basic wants, such as food and shelter, there is little or no correlation between a country’s average income and the happiness of average person. Past some threshold, increases in the good and bad appear to cancel each other out, and the useless slice of the income pie can get pretty fat.

Since national income isn’t the same as well-being, growth in national income isn’t the same as improvement in well-being. All too often, this crucial distinction gets lost in acrimonious debates about the relationship between the economy and the environment.

Forty years ago, a report called The Limits to Growth drew attention to the indisputable fact that our planet does not have an infinite capacity to serve as a source for raw materials and a sink for waste disposal. In choosing to call this idea the “limits to growth,” the authors fell into a rhetorical trap that has haunted environmentalism ever since.

The problem is that most people believe that growth is good. When they think about the national income pie, they think about the good slice, unlike environmentalists who think about the bad slice.

Because they’re really talking about different things, proponents and opponents of growth often talk right past each other. And when they assume that the good and bad are inseparable, both sides buy into the myth that there is an inexorable tradeoff between economic well-being and environmental quality. If the good and the bad must go together, they must grow together.

The result: growth wins, and environmentalists play damage control.

To find a way out of this impasse, we need better measures of economic well-being, better public policies, and better language.

A growing number of economists recognize the need to develop new measures of well-being that count the good as positive, subtract the bad as negative, and ignore the useless. In 2009, the international Commission on the Measurement of Economic Performance and Social Progress, chaired by Joseph Stiglitz, Amartya Sen and Jean-Paul Fitoussi, produced a powerful and wide-ranging critique of the conventional measure of national income. In the U.S., dozens of state-level initiatives are now experimenting with different ways to measure well-being.

In the policy arena, we need to both advance human well-being and protect the environment on which it ultimately rests. This requires not only sound regulations, but also true-cost prices to orient investment and consumption decisions to the full range of costs and benefits. In climate policy, for example, although regulations such as those recently announced by President Obama can help promote the clean energy transition, in the absence of a price on carbon emissions there will always be strong incentives to burn cheap fossil fuels.

Last but not least, we need better language. We need to move beyond the stale “pro-growth” versus “anti-growth” rhetoric of the past. It’s time to raise a new banner: Grow the good and shrink the bad.

Grow the good and shrink the bad.

What does the bad become in the National Income pie when it shrinks, useless, good or does the pie get smaller?

What does focus on National Income tell us about how to deal with our inequitable Rule of Law?

What does focus on National Income tell us about how to deal with the ruling plutocracy that has society staring into the abyss?

I am intrigued by the colors Rome makes while it burns………………

Should we enjoy this almost cavalier criticism of criminal justice? We read here an antiseptic, clinical conclusion of a system that destroys lives largely for profit under the guise of “justice” as something that “doesn’t make us better-off “.

It’s growth and big money, “bad” doesn’t mean a thing. Foreclosing and throwing people into homelessness is “good” because it is big money.

at minute 6:00, linked video states that 6 U.S. investment banks offshore profiteering-derivatives account for 56% of U.S. GDP:

http://www.nationofchange.org/too-big-fail-all-warning-lights-are-flashing-red-video-1372169162

This is in my humble opinion the best economic/business website on the internet at present. It is number 3 in most visited economic/business websites in a recent survey. For the time being it provides a monthly archive without a daily index inside. If a daily index can be provided, it will be perfect! Thanks for this excellent web site nevertheless.

After further browsing, only the current month lacks title index (and one has to go through the extract of each article instead). All prior months have title index. This is a bit unexpected, but just a small dent on an excellent web site. So please ignore my previous comment.

I made the same mistake.

Well-being as used here continues to embody the neoclassical notions of a concept, well-being, expressed as a summation of the individual well-being of interchangeable autonomous agents, and created by their interactions with the economy, which is at once treated as an autonomous entity and another summation of their individual actions.

We need to see that our well being as both individuals and a society is not a partial product of an otherwise independent economic process. The economy’s sole and only purpose for existing is the social purpose we set for it, which is the kind of society we commit to build for ourselves and each other, one which guarantees to each of us the basics for a decent, fair, and meaningful life. This is not just what well-being should be about but any discussion of economics. Economics divorced from social purpose is just cover for theft. Well-being outside the context of social purpose is just personal gratification.

Good point/s. And when I really think about it (respectfully appreciating the well-meaning and intellectually gargantuan efforts involved) … who would I trust to measure my well-being? How would I measure another’s? If a chart said I was in the bottom 20% for “well-being” would I believe it? Do I think the apparently mega-rich are better-off? What I really think is that until I quit that bollocks tendency of defining self by comparison to other selves, the system has me by the short and curlies.

I am reminded that as a student in South Africa, after an evening as a guest in Cristina Lemakaya’s Crossroads shack, I asked her if she was troubled working as a domestic servant each day in better-off white homes. Using a typically African simile she suggested all humans carry a burden on their heads; some appear smaller than others, but they all weigh the same.

Right! But who doesn’t like a smaller headpiece?

This is the mythic rationalization used by the underclass to keep their heads from exploding minute by minute. It is also the view that no matter how unjust things are materially, there is some kind of spiritual accounting that makes it all OK. It’s utter bullsh*t. One can understand and sympathize with the need for the exploited to keep a tight reign on their anger without assenting to this nonsense.

“Economics divorced from social purpose is just cover for theft.”

!

Need for measurements has long passed the questionable stage. It’s absolutely a must. That doesn’t mean that measurement cannot be wrong and conceptually flawed. There are in every field numerous cases of meaningless measures, wrong measures and wrong measurement.

The recent riots in Brazil remind us that we must not only gauge the progress wisely, but also keep an eye on the income gap (alas reluctantly). The economy of Brazil has been on a tear in recent years as one of the BRIC nations, but the wealth concentration into a few hands destroyed the quality of life.

In a TV program I saw today, a person who moved to Brazil was rubbed 14 times in a few months. The third day he arrived in Brazil, a boy pointed a gun at him at a red light and took his belongings and car. A reporter said she felt for her safety walking in the main street of Rio de Janeiro.

This is not the kind of life a person would like to live — no matter how rapid the GDP rose. A society that sees 22% of the population live in poverty and resort to violence and riot will not be able to enjoy the fruit of its harvest.

None of these fear and devastation shows in the economic data.

Another flaw of the quantitative approach in terms of currency units comes from variations in asset prices. Homes are good but quantifying them by their value in dollars instead of units or square feet, for example, is misleading as we have witnessed during the housing bubble.

An excellent critique of The Limits to Growth. It should have been called, The Limits to Exploitation.

Last week, I explained to my 11-yr old the difference between fair and equal. Usually, there is a difference in size between the mother and the father; so I asked her if, to make a fair trade, the food between the 2 should be distributed equally or proportionally. Her reaction was priceless. I could tell that she had to think hard to accept the reasoning behind a fair proportional split.

We quantify too much, and qualify too little. Even worse, thanks to innumeracy and many other reasons, we tend to quantify subjectively.

As long as our money system is based on hard asset collateral and that we focus our GDP growth on energy and resource intensive endeavours, there will be limits to growth and employment.

+100

both sides buy into the myth that there is an inexorable tradeoff between economic well-being and environmental quality

———

The natives would settle and wen they did well, the population would grow until the land’s productivity would dwindle and population declined to the point of forcing them to leave and settle elsewhere. Despite living in symbiosis with nature, they still could not make their lifestyle sustainable for more than 100-200 years.

I don’t believe our way of life is sustainable in any way. We can buy a few extra decades of consumerism but we will be forced into material austerity.

“We can buy a few extra decades of consumerism but we will be forced into material austerity.”

Perhaps when “we” are forced into material austerity (I trust you mean the 30 percent or so of the population who are not already there) we will learn how to become kind, loving, creative, and generous with our time and energy.

The evidence seems to show that a life based on the acquisition of material goods is a mean and empty one, because indeed, the best things in life are not things.

I believe there is enough work, food and shelter for everyone but that would require a change in paradigm which I do not see coming anytime soon. First of all, materialism would need to drop, then the owners of hard assets would need to share and/or redistribute their share.

I believe printing is the solution and we will print. But the wrong way. It will be done in an energy intensive way which will lead to more devastation.

Therefore, I believe material wealth for most of the population will drop over time. Does this lead to more happiness or less, I have no idea. All I can say is that when reading the comments here and witnessing the level of anger and the strong Western visceral attachment to material solutions, I tend to see bitterness before achieving world peace.

I trust you mean the 30 percent or so of the population who are not already there)

———–

Even if wealth has erode for 70% of Americans, there is still a wide gap between the average Chinese and the average American.

In my heart, I want us to work together and fix our monetary system but I fear there will be a convergence between the Western world’s and the emerging market’s material lifestyle over the next few decades, especially if global population goes from 7 to 9 billion!

When resources are plentiful, we tend to share. IMO, the rising wealth discrepancies are evidence of the emergence of physical material imbalances.

In my mind, it is clear that Americans have no idea of how energy intensive their lifestyles are even is they are not in the top 30%.

“When resources are plentiful, we tend to share.” (Moneta)

An intriguing statement. However, it didn’t happen with coal or oil. Unlikely as it may seem, suppose a marvelous new energy source appears. Would anything different happen?

I don’t understand how you could say that after the spendthrift ways of the middle class over the last 60 years.

When was the last time you mended a sock?

“When was the last time you mended a sock?”

Moneta, I must confess that I have never mended a sock. But I do know what a “darning egg” is, because I watched my dear, late mother darn socks. She also had a bathrobe that I swear was more patches and mending than original cloth. She was a true mother: there was almost nothing she couldn’t fix. Not always because she had to, but always because she WANTED to.

My mother was a graduate of the Juilliard School and an assistant professor of music at Vassar College when she threw it all over after WWII to marry and have children. She was a disciple of Henry George, because her mother and grandfather had taught her that it was wrong for less than 5% of the people to own more than 95% of the land…that this effectively enslaved the great majority of people.

When my mother spoke to me about her personal experience of the Great Depression, it was almost always about how much people helped each other during very hard times.

She was not materialistic. That was her great wealth. And her great gift to me.

“In my mind, it is clear that Americans have no idea of how energy intensive their lifestyles are even is they are not in the top 30%.”

I’m curious why energy intensity is your standard? It’s generally understand that we only use a tiny fraction of the net available energy the Earth absorbs from the sun (particularly for solar panels and wind turbines).

Furthermore, much of the energy we do use isn’t really chosen; it’s forced through the incentives created by public policy.

I don’t want to claim that technology can simply magically solve problems. But I would suggest that public policy, not technology/energy/resources/the ‘natural world’, is our primary constraint in the 21st century.

Perhaps in another few thousand years of tech advancement we’ll hit some sort of resource wall, but that’s for our (very) distant descendants to tackle. Our contemporary challenge is distributional.

I look at everything through energy and resources because every single thing we do depends on those.

Without oil, there would not be 7 billion people on this planet because there is no way we could produce enough food to feed 7 billion people without deforesting the entire planet. Here in Canada, it is amazing the amount of farmland that is now fallow… this is land from 50-100 years ago when the population was MUCH smaller. Without oil, we need a lot of land to produce a little. On top of it, we are building McMansions on the most fertile land!

Here in Canada we get 1 harvest per year maybe 2, in many parts of the US, you can get many more… our land is much less productive. This means we should limit our population growth unless we are willing to become dependent on other countries for our food source. IMO, in terms of national security, competitive advantages are a farce.

When populations do well, they use up their resources until depleted. Then they go scavenging for others’ resources like the US has been doing since the 60s or even earlier. Populations will always consume as much energy as they can because:

1. people are insatiable.

2. use it or lose it… somebody else will use their energy if they don’t use it

3. and the most important reason of all is that it is energy that permits a population to stay stronger than its competition and exploit their resources.

I do agree with your policy argument and the fact that we are only using a small fraction of the earth’s energy.

But environmentally, we could manage to exterminate ourselves without using all the untapped energy.

There are other sources of energy, but I seriously doubt we could develop and market technologies fast enough to make our current retirees rich.

Furthermore, I believe that a new form of cheap energy would just help accelerate global population growth which would guarantee an even faster devastation of our planet.

Maybe I’m a pessimist but the reality is that over my lifetime, despite our incredible technological innovations, material goods have never been so plentiful but the environment has been getting exponentially worse. Therefore it is quite hard for me to believe that we will reverse it.

I would like to see evidence on two fronts:

1. That humanity is insatiable in terms of population growth.

2. That plentiful local resources are related to population growth.

The data we have seems to suggest exactly the opposite. Wealth is correlated with lower birth rates and higher demand for environmental protection and social stability and the nonmaterial realm of purpose and justice and exploration and so forth. And not only does that match the evidence, it’s also intuitively logical – people have to meet their basic material needs first. But after doing so, the marginal utility of gathering additional physical resources pales greatly compared to other uses of time.

Indeed, it requires tremendous public policy incentives – including outright force as the most basic weapon of the authoritarians – to make people use their time ‘responsibly’ rather than ‘frivolously’.

The first thing to understand about exponential growth is that it is impossible in a finite world. The entire economic structure of capitalism, be it western vampire capitalism or all the varieties of state sponsored capitalism, requires continued growth for its survival. Ask any politician or economist to pick a number for the ideal rate of growth and the consensus will likely fall around 3% per year. Do the math. A three percent annual growth rate of anything, SUV’s, I-Pads, babies, ears of corn, or for that matter grains of sand would cover the entire face of the earth in about 400 years.

So sustained growth is impossible. We have the choice of living on the planet as a member species in its ecosystem or over running its capacity to support us and experiencing a population and societal collapse just like lemmings or yeast in a jar. There are no other alternatives.

Of course there are less and more just ways of distributing the short term wealth created by an industrial system built upon cheap fossil fuel energy. Criminal banksters flaunting 300′ yachts in the face of starving children is not cause for celebration. GDP numbers have little meaning beyond their use in propaganda. And happiness cannot be measured by consumption once basic needs are met. But we should not think that eliminating blatant injustices is the solution to the dilemma of a species that has grown so dominant and powerful that it has the capacity to destroy its sources of food, water, climate and supporting ecosystem.

I especially liked the “good slice/bad slice” concept. Many of Yves’ excellent points would be crucial aspects of a steady state economy. The conflict between growth and environmental protection, limits to growth, alternatives to GDP as measure of well-being, etc. Brian Czech elaborates on all these ideas in his new book Supply Shock. Also see the site steadystate.org for more solid info.

“So sustained growth is impossible.”

That still hinges upon the definition of growth, though.

It’s a bit like saying the sun will explode one day. Sure, but worrying about the Earth billions of years from now is a bit past our most crucial time frame. Most likely, our descendants will be much better off by then, or they’ll be extinct. There aren’t too many other possibilities.

I think something that has deeply and perhaps unconsciously infected the defining of growth to be resource usage is the false premise that our species is a cancer, that we naturally want to devour everything at a level that kills the larger system.

I think the opposite is true. The population boom of the 20th century was the aberration. What people really want, across cultures and time, is stability and choice and the freedom to follow their pursuits, their desires, that yearning of purpose that sets us apart from our plant and animal friends.

Just to give a specific example, we know that, in aggregate, when people who have their basic needs met have access to contraception, they actively choose to limit their family size. This has been so successful that some places in the industrialized world have been actively concerned about negative population growth. (I chuckle enormously whenever some authoritarian figure grumbles unhappily about rising life expediencies or not enough skilled young people or whatever crap)

A fun tidbit about our own country is that our American born white population is now below replacement level. The entirety of population growth in the US is now happening through immigration and minority communities. The best policy to reduce population growth – the single most important factor in a more sensible relationship with our environment – is to increase the standard of living among impoverished groups!

http://en.rian.ru/world/20130614/181654404/White-Deaths-Exceed-Births-in-US-For-First-Time–Report.html

The question now is what standard of living reduces population growth. The second one is could our planet support 6 billion more with that standard of living.

“the single most important factor in a more sensible relationship with our environment – is to increase the standard of living among impoverished group”

And Education which has devolved into a negative factor of unsustainable student loan debt. I believe a large percentage of college educated 20 and 30 something year olds are mired in college debt. You may ask,how does student debt affect their current and future lifestyles along with their mediocre income ‘lucky to have a job’? No mon, no fun and no hon. In otherwords, they can’t afford a home. No home -no kids. No kids -no buying baby products, services and all the infant paraphenlia on into grammar school, high school and college purchases. Not to mention food production drops, corporations wither away, etc…

If women stopped reproduction, the human species would disappear in less than 100 years. Capitalists need human reproduction, and thus, must provide sustainable living wages with discretionary spending Or we all fall down.

Maybe George Carlin had it right; humans we’re put on this Earth to create plastic and that’s it. We’ve served our purpose and outlived our usefulness

There may never be another genius to equal George Carlin.

“I forgot how to breath!” George Carlin

You fail to understand basic mathematics. I repeat: sustained exponential growth is impossible in a finite world. And not over a period of billions of years as you and most of your fellow Americans would like to believe. If you want to start your education, spend a six minutes listening to this introduction to the concept of exponential growth.

http://www.peakprosperity.com/video/216/playlist/153/chapter-3-exponential-growth

The second point that should not be ignored is that capitalism requires exponential growth for its very existence. Capitalists by definition live off their ability to extract surplus value (rents and interest) from their ownership of labor and productive infrastructure. Failure to compete and grow wealthier means that losers will be conquered and absorbed by other capitalists. Successful competition among capitalists invariably leads to fewer and fewer winners. And as they gain more power they are able to extract more and more wealth from the lower classes– resulting in fewer orders for the goods and services produced by capitalism. It’s pretty hard to grow an economy when consumers have to spend their entire income paying the interest on their accumulated debts—-.

In industrial society the key components that constitute the means of production are energy (concentrated, mobile, and cheap fossil fuel extracted from a finite planetary heritage), physical labor (increasingly irrelevant to the capitalists as production becomes more automated) and Intellectual capital (controlled by maintaining class divisions and ideology.)

In order to continue to grow as its internal dynamic requires, capitalism must exponentially increase its extraction of wealth from the natural capital of the planet. It must also continually increase the size of its markets through greater individual consumption or greater number of consumers.

Capitalism is a system with a finite life cycle because it exists in a world of finite resources and markets. Affordable energy, water, climate change, toxic pollution, necessity of market expansion vs ability of consumers to service debt*—- all are finite limitations upon the capitalist system of social organization. And not a billion years in the future, or even a decade in the future, but right now.

Take away the ability to grow and you no longer have a system that can support capitalists or capitalism. One can always hope that the outcome will be some form of more enlightened cooperation with the millions of other life forms on the planet and a form of growth where wisdom replaces greed and stupidity.

On the other hand humans have no lack of capacity for inventing ways to accelerate population reduction. Religious theocracies, horrors like Stalin’s liquidations, Pol Pot’s madness, the American nuclear bombing of Japan— yes humans have the capacity to drive off the cliff in a number of different ways.

* I’d argue that the 2008 financial meltdown in the US was as much about reaching Peak Debt as it was sub-prime lending.

“You fail to understand basic mathematics. I repeat: sustained exponential growth is impossible in a finite world.”

Of course if you limit the definition to that which is impossible, then it’s impossible. What I’m suggesting is that the physical limitations of this particular planet is not the only way to define growth. GDP does not measure the human spirit.

You seem to be assuming as true the very premise I’m critiquing. I would argue the opposite, that for a time period covering what we humans can reasonably predict into the future, physical resources are not our constraint. Rather, it is our system of public policy that allocates resources that is the constraint.

We don’t need more oil and timber and silver and farmland and whatever else someone wants to claim is scarce. We actually need LESS – less shopping malls in flood plains, less water pumping for industrial agriculture, less commuting to purposeless jobs, less fighting wars around the world, less incarceration and oppression, less useless debt, less McMansion sprawl, less working in general…

Or to say it differently, there is a huge variable your model has excluded.

Time.

By the time we run out of time, our descendants will be so different from us that we probably have no way of even communicating to them billions of years into the future.

If we’re the only reasonably sentient beings in this universe, then we have such massive physical resources available to us that the sheer scale of it is incomprehensible to our feeble brains. If we’re not alone, the human drive for curiosity and exploration and discovery and adventure and making a better life is sure going to want to find that out sooner or later – and if we run into the wrong kinds of neighbors, that’s what will wipe us out, not mathematical models of finite resources in closed systems.

What happened in 2008 was a political event. Just like what happened in 2007 and 2009 and continues happening today. The natural world certainly imposes constraints, but how we deal with them in our immediately knowable future is a choice of policy, not a dictated conclusion of hitting limits in the physical world.

I have found professors of happiness hapless. Crooks usually make other people very unhappy. The idea, presumably, is to make societies in which crooked behaviour is more or less impossible and unnecessary. This is tough because primitive human societies are violent and have daft cultures – so the idea of getting back to some default ideal ‘human nature’ is a fiction.

In any scenario I can come up with we will need to police society and have some kind of military. Thus one of my first economic questions, as I want democracy, is how to keep policing-military democratic. The only way I can think of is for us all to take part in the process. We could have national-international service as part of a job (income) guarantee and require 5 years from everyone.

This would remove unemployment from an economic lever system, and necessity excuses for crime.

Simples! What really gets to me is that we don’t seem to be able to even discuss whatever we can come up with like this or alternatives to it. I disagree with Yves in emphasis that it is about collecting harder qualitative data and see it more as that we tend to bandy numbers about in ‘spreadsheets’ left to us by 17th century pundits refined by their scholastic acolytes. You can bet the creep using unemployment in anti-inflation talk won’t suffer it. The numbers in use rely on massive exclusions to add up. A typical bacteria colony in-vitro will poison itself long before it has used up the nutrients in the substrate and any really long-term human survival clearly needs us (in some form) to leave this planet, not poison it and so on. I’d go for including more stuff we can measure and estimate before bothering with the happiness-type thingy-whatever-you-feel-like-today speculation.

And we have to stop people cheating with numbers by pretending their models are accurate, scientific and the only ones worth looking at when there are many alternatives.

I’m not against happiness or qualitative research. It’s more that I don’t think those flirting ‘qualitative sounds’ really understand the underlying structural realism on which theories form (and are formed) – Ludwig, Sneed etc in physics. In the end though, we need some spreadsheets and databases that, in principle, anyone can use (I mean the modelling not the programs themselves) and allow radical planning and thought experiments we can cost, at least in principle. We don’t even seem to understand machines do much of the work these days and that jobs aren’t coming back. We are still using the same models we had before we got half-way to robot heaven – which is so dumb as to make anyone wonder just who is steering the ship.

“…one of my first economic questions, as I want democracy, is how to keep policing-military democratic. The only way I can think of is for us all to take part in the process.”

Yes, and taking part in the process means a couple of things. In particular it means *both* contributing a fair share and also receiving a fair share. It is not going to work, even if everyone contributes service, if some people benefit more from the police-military system than others as when the plutocracy uses our police forces to protect themselves from us while we get no protections, but fines, arrests and imprisonments.

“The only way I can think of is for us all to take part in the process”

Or as Bill Still says, we’ve got 2 choices: serfdom or self-governance.

And, he points out, not very long to make up our minds.

Indeed, but this is old news, and part of a larger story.

I am old enough to remember when we judged an economy in more practical terms: how many hours of labor does it take the average worker to buy a pound of butter, a gallon of water, a lumen-hour of light.

But now we have abandoned these more practical metrics and focus entirely on economic growth per se. Part of this of course is that using the old metrics would show that most people are losing ground, and that would embarrass the wrong people.

But part of this is surely the shift to a rentier-dominated society. Suppose that we took Switzerland and turned it into India. The economy would be very much larger, the rich would be very much richer, but the average person very very much worse off.

The rich care only about total economic growth: it matters not to them if it is due to a modest number of people making more money or a larger number of people living in poverty (ignoring for now distributional effects). The average worker cares about real physical per-capita wealth.

If the economy needs to grow 6% to handle population growth (typically industrial economies have to grow faster than population to keep even because of capital expenditures and increased resource extraction costs), but the economy only grows 3%, the average person has lost ground, but the rich see a 3% gain (although increased unemployment would likely magnify this gain due to lower wages). And that is about all that our economists and press are concerned about.

Happiness capital. I like the comments more than the post. We should look at national service and engagement rather than allowing ourselves to be so disenfranchised. What is the necessary standard of living for our society? For our advanced society? I beg to differ that we are going to run out of resources. Not because I want to pillage the environment – just the opposite. We wind up pillaging the environment when we are over-productive and working to pay of interest on the debt. For my part I would keep happiness and flush debt down the toilet. Since all things financial are rigged, I don’t see why we cannot do this now – before the demands of debt over produce, deplete the world, and cause even higher levels of inequality. Who says “growth” has to go upward and onward? It can go around in circles if we choose.

I think we have a lot of this upside down Susan. The post at least says loads of growth is useless tat. I forget how long it is before Earth is very difficult to live on, and we’re not so sure about the heat death of the universe anymore. There are signs population may be coming under control. I don’t know what figure I’d put on how much ‘growth’ is ‘waste’ – more than half?

With all the oil and gas gone we haven’t run out of resources – in such circumstances my mate’s petrol from air machine running on Hebrides’ wind might be ‘economic’ simply because the cheaper stuff has gone.

In simple terms I’m just sick of the lack of an economics that let’s us get on now with what might matter in a future time when whatever is around with human lineage understands why we were clinging to this rock. I suspect we’d be hard put to describe whatever leaves Earth to travel the stars as biological.

I think the resource we are losing fastest is democracy. In contributing and receiving from national-international service and having it as a safety net, the employment relationship changes, hopefully towards more employee dignity or creative self-employment.

I had a time and motion stop watch (100 secs in a ‘minute’) and remember simpler methods on production than now. I suspect all growth claims attributed to finance may be chronic lies and would be more accurate with a minus sign in front of them.

Let me point out that that common stock, besides being an ethical form of endogenous money, ALLOWS but does NOT REQUIRE growth.

So tell me again why we have a government-backed credit cartel to drive people into debt for usury when usury REQUIRES exponential growth just so the compound interest can be paid?

Because without debt how can the populace be controlled?

The economic system is about control and exploitation of the populace for a small elite, much like feudalism was.

To be fair though, Feudalism was never a ponzi scheme…

Because without debt how can the populace be controlled?

That’ll work till it doesn’t.

One fundamental problem with resolving the conflicts of growth versus the environment versus distributive justice is that human beings, whether acting individually or collectively, are not smart enough to derive any intellectually rational or socially satsfactory planned solution to any subpart of this conflict, and never will be.

The other fundamental problem is that incorrigible human beings will not stick to any such plans that the wise of their elder generations lay out for them. They will rebel. If they cannot rebel overtly, they will undermine.

The theory that such conflicts can be resolved in a democracy or through negotiations, also does not hold any promise. Individual human beings do not have good capacity to govern their own individual affairs: some persons can manage some of their own affairs prudently at some times in their lives, but others never can, and no one always can. If they can’t do well as individuals managing individual problems, why would anyone think that human beings can do better when persuading or negotiating with others to resolve common conflicts?

There’s a free book here that at least suggests much we are being told will help us grow (finance) in fact does the opposite – http://www.taxjustice.net/cms/upload/pdf/Finance_Curse_Final.pdf

In terms of widening the issue, I tend to think the problem with economics is it pretends (in mainstream) to be a science like chemistry where how you want to live is of little subject significance. I think how we want to live defines what economics we want to try. This repeatedly drives us away from inclusive discussion.

It seems in the UK we have now become so excluding that our major review of banking following the crash was carried out solely by bankers at the problem defining and investigation stage. It’s like letting Mr Fox investigate he raid on the hen-house.

Why we should act as though neo-classical economics can guide even our questions given it is as relevant to what we want to achieve as a Dead Sea scroll, is beyond me.

“Why should be act as though neo-classical econmics can guide even our questions….?” Of course I agree with your question, although I would never seek the guidance of heterocox econcomists, either. But I propose that there may be some reasons why some of us do act as though such persons can offer guidance: (1) we are moved by compelling emotional demands to seek solutions to our problems, even when there are no solutions, or at least explanations as to why we have them, and so we repair to any charlatan who offers, however fraudulenty, to meet our emotional demands for explanations and solutions. (2) The professional work of economists is twofold; first, to explain, and second, to justify, the workings of the (allegedly observable, comprehensible, explicable, and justifiable)economic system, and persons who do such work have ample opportunities to make good livings telling their paying customers whatever it may be that those customers want to hear.

How can such things be? Well, in American jurisprudence we have a compelling consitutional doctrine that favors free commerce in the marketplace of ideas. Economists prosper because their is no consumer protection agency in the marketplace of ideas, unless peer review by economists themselves should count–it shouldn’t.

When I follow a debate between economists of two opposing schools, I tend to conclude that both are losers. But there isn’t much point in following a debate between promooters of two incorrect systems of thought.

Economics is a science. The problem is that it is still in its infancy… our theories are stuck at the earth is flat level.

Economics is a Religion. Does economics exist in the natural world or is it an ideological state of mind? That is to say, ideology is abstract and it’s ideology praxis that creates a physical reality through the subjects actions. As an example, we can’t see a god but the physical and symbolic practices of the ideological subjects(bowing, kneeling, praying, etc…) creates a physical reality that is interpreted as proof that a god exists through these human actions. What’s the point? Is money real or abstract? Money is a collective psychosis-consensus that ink-colored paper, metallic coins etc…have a ‘real’ designated value that is exchangeable for our labor. Thus, we enter into an ideological agreement through our daily actions of exchanging these ‘valued’ slips of paper when in reality they are just simply pieces of paper with numbers and ideologic symbols (pyramids, eye, eagle, etc..).

“Since national income isn’t the same as well-being, growth in national income isn’t the same as improvement in well-being. All too often, this crucial distinction gets lost in acrimonious debates”

This. Cannot be said enough.

Ending bad spending is a Good Thing, no matter what sector financial balances blather is warped to claim about the economic utility of prisoner abuse and warrantless searches and missile defense and financial bailouts and drone strikes and sticking hands down people’s pants at airports and direct to consumer advertising of prescription drugs and ridiculous patent and copyright laws and restrictions on cross border trade and paying hospitals and universities to have six and seven figure administrators and…

Kurt Vonnegut spoke to my college class and gave this simple advice: “Don’t steal. Don’t raid the public treasury. Don’t work for people who steal or raid the public treasury.” Contrarily, some economists of the who-cares-if-there’s-a-little-fraud?-variety seem to think that stealing and raiding the public treasury are OK, as long as the ill-gotten gains are spent on goods and services that add to measured GNP. Economics is not a value-free science; it has values. It’s just that they are the wrong values.

I share the attitude Bulldog. I used to think different arguments were different because basic assumptions and root metaphors made argument paradigmatic. I now doubt people often have the ability to get the facts straight, kick down enough doors and do the leg work to get the evidence. Instead we get incomplete argument on theory, most of which is copied. The professors don’t care – we pay them all.

In costing a new product or service provision we are supposed to do opportunity costing – how much would we make if we just left the project costs in the bank etc. – and yet on estimating the value of financial services to our GDP (why not GNP for a tad more accuracy?) we don’t subtract the losses in agriculture and manufacturing since ‘big bang’. In the UK I get readings of plus 14% to minus 35% depending on what I include. I suspect the financial turds cost us more than the NHS, but wouldn’t claim that if I wrote a paper, but express the range of possibilities.

Argument has about 9 components with different directions, purposes and outcomes. We had television on in the morning yesterday. Some angular gawp in a frock fitting like a sack was talking economics as a way of warming up the Teletubbies audience. I have no idea why the BBC let anyone this stupid or ugly into my living room and was about to switch off when it dawned on me a ‘what was wrong with that’ question might throw something useful up in a 101 class next year. I watched the three minutes I recorded in agony, thinking of my nine component model of argument. She didn’t meet any as making me feel 4 years old and brain-dead aren’t on the list.

Economics students score worst on ethics tests. Although I teach the muck I’m self-taught. I show people I teach a few cheats to get through the day and run some games that simulate serious fraud. I get the feeling the kids think this s the ‘how to do it for real’ bit! A few can spot it’s a crock and ask for something different.

What? No mention of the Genuine Progress Indicator? It’s been around for years and years:

http://www.rprogress.org/sustainability_indicators/genuine_progress_indicator.htm

The author first tells us that, once we’ve satisfied basics, there is not much greater wealth can do in terms of happiness, so we need a method for classifying as “good, bad, and useless”.

Then, we’re informed that the “useless” category contains every good or service we buy which serves only to reinforce our social standing, which means we buy an enormous amount of useless stuff.

Finally, we’re read that: “A growing number of economists recognize the need to develop new measures of well-being that count the good as positive, subtract the bad as negative, and ignore the useless.”

This is absurd. The “useless” is what makes up the bulk of our consumption economy. It is hard fact that it is the “useless” that is killing us and our planet that needs to be pounded into everyone’s head. In other words, “useless” is as “bad” as it gets. Once we mature as a society to embrace this vital point, we can move on to re-organize economic activity that leaves out the useless entirely, which means fewer “jobs” or fewer “hours worked” but entails far more leisure time in which to pursue true “goods”. Today, the entire culture is stressed to the 9’s, works far too many hours, often for little compensation but plenty of debt, and have neither time nor income to enjoy real “goods”, but nonetheless must buy clothing, gadgets, housing, furnishings, car, whatever according to the laws of the useless, rather than whatever works well and comfortably – which would tremendously reduce both the “useless (bad)” in tandem with the just plain “bad”.

Once we recognize there’s no need for most of the crap we crank out, we can finally get around to constructing the sort of society that can provide decency, comfort, education and arts, sports, and all the other “goods”, including the greatest good of all, which is to be able to replicate it long into the future without savaging either humanity or the rest of the biosphere.