Yves here. I guarantee this post will make some readers’ heads explode. It also explains why Germany would benefit from OMT.

By Paul De Grauwe, Professor of international economics, London School of Economics, and former member of the Belgian parliament, and Yuemei Ji, Economist, LICOS, University of Leuven. Cross posted from VoxEU

The monetary-fiscal policy connection is under scrutiny by the German Constitutional Court in the context of the ECB’s OMT bond-buying programme. This column argues that most analyses are deeply flawed by the misapplication of private-company default principles to the central bank. ECB bond-buying transforms public bonds into monetary base, and sovereign-default risk into inflation risk. The real question is: What is the non-inflationary limit to money-base expansion? This depends upon the economic situation and is much higher in the current liquidity-trap setting.

There is a lot of confusion about the fiscal implications of the government bond-buying programme – the OMT, or Outright Monetary Transactions – that the ECB announced last year.

This confusion arises mainly because the principles that guide the solvency of private companies (including banks) are applied to central banks.

• The level of confusion is so high that the president of the Bundesbank turned to the German Constitutional Court arguing that the OMT programme of the ECB would make German citizens liable for paying taxes to cover potential losses made by the ECB.

• In this column we argue that the fears that German taxpayers may have to cover losses made by the ECB are misplaced. They are based on a misunderstanding of solvency issues that central banks face.

Indeed, German taxpayers are the main beneficiaries of such a bond-buying programme.

Solvency Central Banks Versus Private Agents: The Key Difference

Private companies are said to be solvent when their equity is positive, i.e. when the value of their assets exceeds the value of their outstanding debt. The solvency of a private company can also be formulated in terms of the maximum amount of losses that a company can bear at any given time. Thus, a private company is said to be solvent when its losses do not exceed the value of its equity. Since in efficient markets the latter is equal to the present value of future profits, we arrive at the solvency constraint that says that the losses today cannot exceed the present value of expected future profits.

The problem arises when these solvency constraints are applied to central banks.

• This misapplication of private principles has led some to conclude that the loss the ECB (or any central bank) can bear should not exceed the present value of future expected seigniorage gains (see Corsetti and Delado 2013).

• Similarly, it is sometimes concluded that a central bank needs positive equity to remain solvent (Stella, 1997, Bindseil et al. 2004).

These solvency constraints should not be applied to the central bank; central banks cannot default.

A central bank can issue any amount of money that will allow it to ‘repay its creditors’, i.e. the money holders.1 Such a ‘repayment’ would just amount in converting old money into new money.

Contrary to private companies, the liabilities of the central bank do not constitute a claim on the assets of the central bank. The latter was the case during gold standard when the central bank promised to convert its liabilities into gold at a fixed price. Similarly in a fixed exchange-rate system, the central banks promise to convert their liabilities into foreign exchange at a fixed price.

The ECB and other modern central banks that are on a floating exchange-rate system make no such promise. As a result, the value of the central bank’s assets has no bearing for its solvency. The only promise made by the central bank in a floating exchange-rate regime is that the money will be convertible into a basket of goods and services at a (more or less) fixed price. In other words the central bank makes a promise of price stability. That’s all.

Seigniorage is not a Limit

Thus it makes no sense to state that the limit to the losses a central bank can make at any point in time is given by the present value of future profits (seigniorage). There is no such limit. The central bank can make any loss provided the loss does not endanger its promise to maintain price stability.

Also it is not correct to claim that the central bank needs to hold positive equity ‘to remain solvent’. A central bank needs no equity. As a result the claim that is sometimes made that a central bank with negative equity needs to be recapitalised by the treasury is senseless. To be clear:

• The central bank (that cannot default) needs no fiscal backing from the government (who can default).

• The only backing the central bank needs from the government is that it can keep its monopoly power to issue money in the territory over which the sovereign has jurisdiction.

With that power granted by the sovereign the central bank is freed from any solvency constraint.

Let us now apply these first principles to the issue of how a bond-buying programme can have fiscal implications. We first discuss the situation of the central bank that faces only one sovereign. Then we discuss the problem of the central bank in a monetary union facing many sovereigns.

The Central Bank of a Stand-Alone Country

We will consider the case of a central bank that buys government bonds in the secondary market.2 By buying government bonds the central bank transforms the nature of the public-sector debt.

When the central bank buys its government’s debt, the debt is transformed:

• Government debt that carries an interest rate and a default risk becomes debt that is a monetary liability of the central bank (money base) that is default-free but subject to inflation-risk.

To understand the fiscal implications of this transformation, it is important to consolidate the central bank and the government (after all they are separate branches of the public sector).

After the transformation the government debt held by the central bank cancels out. It is an asset of one branch (the central bank) and a liability of another branch (the government). As a result, it disappears. The central bank may still keep it on its books, but it has no economic value anymore. In fact the central bank may do away with this fiction and eliminate it from its balance sheet and the government could then eliminate it from its debt figures. It has become worthless because it was replaced by a new type of debt, namely money, which carries an inflation risk instead of a default risk.

This is why It makes no sense to say central banks lose when the market price of the government bonds drops. If there were a loss for the central bank it would be matched by an equal gain of the government (whose market value of the debt has dropped in the same proportion). There is no loss for the public sector.

Public Debt Held by the Public Sector is Different

We arrive at an important conclusion:

• When the central bank has acquired government bonds, a decline in the market value of these bonds has no fiscal implications.

The loss in one branch of the public sector (the central bank) is offset by an equal gain in another part of the public sector (the government), leaving nothing to be paid by the taxpayer.

Another way to see this is to look at the interest-rate flows underlying bond holdings. Let’s take an example and suppose the central bank has bought €1 billion of government bonds. These have a coupon of, say, 4%. Thus the central bank that keeps these bonds on its balance sheet receives €40 million from the government every year. The bookkeeping practice is to count this as profits of the central bank. At the end of the year the same central bank will have to hand over its profits to the government. Assuming that the marginal cost of managing this bond portfolio is zero, the central bank will hand over €40 million to the government. This is the left hand paying the right hand, so to speak.

This bookkeeping practice has led to the perception that the interest revenue is to be considered as seignorage. It is not. There is no profit for the public sector. The profit of the central bank is exactly offset by a loss of the government. Both could do away with this bookkeeping convention because there is no economic substance to these losses and profits.

• It is literally true that the central bank could put the government bonds ‘into the shredding machine’; nothing would be lost.

In our example, the central bank would stop receiving €40 million a year, and would stop paying out €40 million to the government every year.

What happens if the government defaults on its outstanding bonds?

• Default leads to losses for private holders of these bonds.

• But it is immaterial for central bank-held bonds.

These are now valued at zero, but they were also already worthless before the default. This is the right hand taking it back from the left hand.

Think about it in terms of the interest flows. After the default, the central bank stops receiving interest payments from the government, but by the same token it stops paying these back to the government. Nothing has happened in the public sector. Thus the loss that the central bank is making as a result of the default has no fiscal implications.

Price Stability and Public-Sector Default

There is an issue when it comes to price stability and its link to a government default. If the central bank keeps its liabilities (money base) under control, the default by itself will not lead to more inflation. The latter will arise only if the government were to force the central bank to issue more of these monetary liabilities, e.g. to finance current budget deficits that after the default the government cannot finance by issuing bonds anymore.

It is sometimes argued that if the central bank has no assets (because of a default by the government), then it no longer has instruments to reduce the money stock. This may sometimes be necessary to reduce inflationary pressures. This argument does not hold water. There are two ways a central bank that lacks assets can reduce the money stock.

• First, the central bank can issue interest-bearing bonds and sell them in the market.

This has the effect of reducing liquidity (money base).

• Second, the central bank can raise minimum reserve requirements.

As a result, the existing stock of liquidity is ‘deactivated’, which has the same effect of a decline in the money base.

The Central Bank of a Monetary Union

Things are more complicated in a monetary union that is not also a fiscal union. Here the fiscal implication of central-bank bond buying is more complicated. The crux is the presences of ‘n’ sovereigns. In the Eurozone, n = 17 (soon to be 18 with Latvia).

• If we could consolidate the ECB and the 17 sovereigns into one public sector, the analysis would carry through unchanged.

• But we cannot; the Eurozone is not a fiscal union.

As a result a bond-buying programme will lead to transfers among participating member countries.

To clarify thinking about this problem, assume that the ECB buys €1 billion of Spanish bonds with a 4% coupon. The fiscal implications are now as follows.

• The ECB receives €40 million interest annually from the Spanish Treasury.

• The ECB returns this €40 million every year to the EZ national central banks.

The distribution is pro rata with national equity shares in the ECB (see ECB 2012).

• The national central banks transfer this to their national treasuries.

For example, the ECB will transfer back 11.9% of the €40 million to the Banco de España. The rest goes to the other member central banks. The largest receiver is the German Bundesbank; with its equity share of 27.1%, it would get €10.8 million.

Thus in a monetary union (and in the absence of a fiscal union) a bond-buying programme leads to fiscal transfers among countries – but not the one common in the public perception, especially in Germany.

• An ECB bond-buying programme leads to a yearly transfer from the country whose bonds are bought to the countries whose bond are not bought.

It should be noted that the ECB could implement a bond-buying programme that avoids fiscal transfers by buying national government bonds in the same proportions to the equity shares of the participating NCBs. This has in fact been proposed sometimes. But this would not eliminate all transfers because the interest rates on the outstanding government bonds are not the same. In fact the countries with the highest interest rates would in this weighted bond-buying programme be net payers of interest to the countries with the lowest interest rates. Thus even a bond-buying programme weighted by the equity shares would involve fiscal transfers from the weaker (debtor) countries to the stronger (creditor) countries.

What Happens Under a Public-Sector Default?

One often hears in the creditor countries that these would be the losers if one of the governments whose bonds are on the balance sheet of the ECB were to default. This is an erroneous conclusion.

Returning to our example of an ECB purchase of €1 billion of Spanish government bonds, consider a Spanish defaults on these bonds.

• The Spanish government would stop paying €40 million to the ECB.

• The ECB would stop transferring this interest revenue back to the member central banks pro rata.

• The German taxpayer, for example, would no longer receive the yearly windfall of €10.8 million.

In no way can one conclude that German taxpayers, or any EZ taxpayer, would pay the bill of the Spanish default – except in the narrow sense that they would no longer be able to count on the yearly interest revenues.

• There is of course the possibility of an inflation tax.

We have noted before that at the moment of the bond buying programme interest bearing debt is transformed into monetary liabilities of the ECB (money base). This by itself could lead to inflation, and thus to an inflation tax that would be borne by all holders of euros. This leads to the issue of how large the ECB bond-buying programme can be without generating additional inflation.

From Explicit Taxation to Inflation Tax

Every open-market operation involving the purchase of government bonds creates the potential of inflation because it increases the money base. The key question we have to ask ourselves is how the increase in the money base is transmitted to the money stock. After all, it is the money stock not the money base per se that determines inflation.

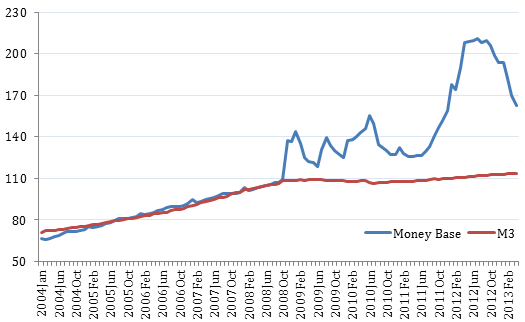

In Figure 1 we show the evolution of money base and money stock (M3) in the Eurozone since 2004. We find a striking difference between the period before and after the banking crisis of October 2008.

• Prior to the Global Crisis, the two monetary aggregates move in unison suggesting that the money multiplier (the ratio of money stock to money base) is constant.

A 1% increase in the money stock led to an increase of the money stock of approximately 1%. Things are very different during the crisis period.

Figure 1. Money base, money stock (M3) in Eurozone (2007 December=100)

Source: European Central Bank, Statistical Warehouse.

Over the period 2008 (Oct) to 2013 (April), the relation between the money base and the money stock breaks down. The money base increased by more than 50%; the money stock increased by only 7%. This suggests that the money multiplier has dropped dramatically.

This dramatic decline in the money multiplier has everything to do with the liquidity trap (Krugman 2010). Banks, which accumulate reserves as a result of the liquidity injections by the ECB, hoard these reserves. Their degree of risk aversion is such that they do not use their cash reserves to expand bank credit. As a result, the money stock (M3) does not increase.

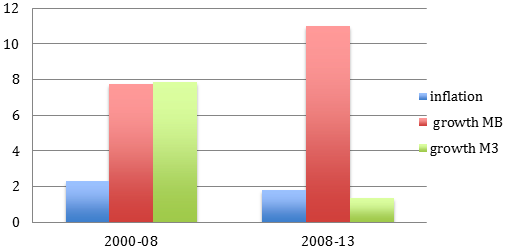

Figure 2 is also instructive. It shows the average yearly inflation rate and the average yearly growth rates of money base and money stock before and after the banking crisis of 2008.

• Prior to 2008 both monetary aggregates increased at practically the same rates; the yearly inflation was 2.3%.

• Since 2008 the growth rate of the monetary aggregates diverges dramatically.

The money base grows at a yearly rate of 11% while the growth rate of the money stock collapses to less that 2% and inflation drops below 2%.

• Our interpretation is that the strong increase in the money base helped to reduce the deflationary forces in the economy, rather than being a source of inflation.3

Figure 2. Inflation, growth MB and M3 (average yearly growth rates)

Source: European Central Bank, Statistical Warehouse.

Conclusions

The previous analysis suggests the following:

• Limits to a bond-buying programme depend on the nature of the economic and financial situation, i.e. the existence of a liquidity trap.

• In normal times when an increase of the money base leads to proportional increases in the money stock the limit to a bond-buying programme is tight.

If the target for the increase in the money stock is 4.5% (as is the case in the Eurozone where a 4.5% target is assumed to lead to at most 2% inflation) this also means that the money base should not increase by more than 4.5% per year. But then during normal times there is very little need for a bond-buying programme.

• The situation has changed dramatically since the start of the banking crisis.

During the crisis period the limits to the amount of money base that can be created without triggering inflationary pressures is much higher because of the existence of a liquidity trap.

How much higher depends on the money multiplier. In De Grauwe and Ji (2013) we estimate the size of the multiplier during the crisis period and we conclude that it has collapsed to zero. As a result, there is no limit to the size of the bond-buying programme, i.e. the ECB can buy any amount of government bonds without endangering price stability, as long as the crisis lasts.

______

1 We assume here that the central bank does not hold foreign currency liabilities. In that case the central bank can be pushed into defaulting on these foreign currency liabilities because it can only issue domestic currency liabilities (Buiter 2008).

2 Thus we do not discuss direct monetary financing of government budget deficits.

3 See Friedman and Schwartz(1961) for an analyis of the Great Depression in the US. These authors argued that the US Fed at the time failed to increase the money base sufficiently to counter the delflationary forces. As a result, the US money stock actually declined, reinforcing deflation.

See here for references

I’m glad there is a growing global realization of the fact that a true central bank has no capital constraint, and that there is no meaningful sense in which its “solvency” would ever have to be backstopped by a treasury. Central banks just use their balance sheet position as one factor in their price stability policy rules. A central bank can run in negative equity forever and still meet all its commitments. Since the banks is the ultimate source of the fundamental monetary unit, terms like “profit”, “loss”, “capitalization” etc. are dubiously applicable to central bank operations. The only question is at what point would negative equity be destabilizing.

De Grauwe has been right on this issue for years but kept in the purview of European affairs.

As for the way Fed runs negative equity I just learned recently that they will do it through an accounting rule change from a couple years ago that allows them to merely accrue as “foregone Treasury remittances”:

http://www.financialsense.com/contributors/bob-eisenbeis/fed-accounting-is-the-problem-solved

So the negative equity that would come from running losses is balanced by a liability account of foregone remittances in the future to Treasury.

So Fed losses apparently won’t balance from Treasury’s books (sparing tax payer of any immediate burden), but appear only on the Fed’s books as a debit to equity balanced by a credit to liability of future payments to Treasury of profits.

‘Paul De Grauwe … former member of the Belgian parliament.’

Loonies like De Grauwe are what makes telling Belgian jokes a favorite pastime of the French.

Q: What’s a Belgian with two brain cells?

A: Pregnant.

Your comment not very funny (to me). My criticism is that I mistook it for a new theory of “limits to expansion.” I have a hard enough time getting my head around Einstein’s cosmological constant, much less new-fangled economic theories. My 2 cents worth — “Sounds pretty good.”

Well, negative equity will become destabilizing when the insanity of the austerians causes the deficit to grow exponentially causing default to be considered the best option, that is, when the pan flies off the handle, the Fed will “print” whatever it can to keep things afloat and every “liability” thus printed will have little indemnification for anyone accepting it and so risk will go nuts. This panic will be seen as price inflation. This is the sort of thing that happens when your insurance company is reduced to the Wizard of Oz because it is out of sync with your goofball “representatives”.

How will the deficit grow without limit?

Isn’t part of the problem that private banks within the EU system did not adhere to the principle of holding foreign currency liabilities?

And now they are asking to be helped out for being sold US CDS crap they lost money on….at least they are acknowledging their losses unlike the Fed.

Is financial obfuscation easier during “active war mongering” like with Syria?

What will the anthropologist write about this shit, assuming some live to look back????

It is kind of important to remember that the reason a country like Spain needs to be issuing a bunch of bonds even as it pursues a vicious austerity program is to finance a backdoor bailout of German and Northern banks, or more particularly German and Northern kleptocrats, not their 99%s.

The real risk is not Spain will default but it will leave the euro and let its banks default, at least that’s how I would handle it. This would effectively stop the stealth bailout by Northern elites of their kleptocratic masters, that is the part running through Spain. I am not saying this likely. It would entail the Spanish throwing out their current political classes and putting in place a government for and by and of the Spanish people.

Agreed. It’s amazing how the main issue seems to almost always take a back burner in these guest posts about monetary policy.

Of course it doesn’t matter how much losses a central bank takes on. What matters is who the central bank gave the money to that is causing its loss. Infrastructure and social insurance are wise investments. Financial crooks and war criminals (and in the US, the healthcare cartel) just waste money by entrenching inequality.

Germany has a particularly unstable system because its export model depends upon extending financing to the very people who otherwise wouldn’t be buying their stuff. Gee, shocker, when you make stupid loans, some of them go bad. Whocouldanode. Surely not Deutschebank or Commerzbank. They’re just victims of austerity politicians who aren’t net deficit spending enough euros and dollars and pounds and yen.

I will be glad when more people realize the true nature of “central banks”, which is to ensure the checks clear, that is all.

A central bank does not have a secret vault with lots of cold hard cash stacked inside. The functions of a central bank that does deal in cash, like supplying cash to a local bank, is done by a non-central bank. The functions that are talked about in the MSM does not involve a vault or cash. They involve the promise of the central bank’s government to pay or not to pay the debt of someone (or some country’s debt).

Unfortunately and most confusingly, people keep talking about central banks as if they do have a vault and do have hordes of hard cash and coin and so they dream up lots of eyes-glazing-over charts, terms, and false cause/effects that really are not true.

Makes me wish for the good old days when everyone “knew” that the Fed/Central Bank set the interest rate and that was the key to the US economy. Then, other financial centers sprang up, other “interest rates” became written into contracts (LIBOR for one), and people could see that the Fed’s interest rate was not so important after all. So the Feds and their followers dreamed up the above charts, terms, and false relationships to keep up the pretense.

Good work if you can get it, I suppose…

I will be glad when more people realize the true nature of “central banks”, which is to ensure the checks clear, that is all. H. Alexander Ivey

The monetary sovereign itself (e.g. the US Treasury) should provide a risk-free fiat storage and transaction service for all citizens and abolish the lender of last resort. And that service should make NO loans (Of course individual depositors could, if they so choose.)

It is normal and good that checks NOT clear when there are insufficient funds.

And notice how the banks punish the hell out of their customers for overdrafts? Double standard much?

Matthew 18:23-35

Everything was going swimmingly until :

Banks, which accumulate reserves as a result of the liquidity injections by the ECB, hoard these reserves. Their degree of risk aversion is such that they do not use their cash reserves to expand bank credit.

Reserves cannot become part of the money in circulation. They live on hard drives at the Fed and remain there unless destroyed by government fiscal operation.

This dramatic decline in the money multiplier has everything to do with the liquidity trap (Krugman 2010). . . . Their degree of risk aversion is such that they do not use their cash reserves to expand bank credit.

Krugman’s conception of a liquidity trap is at odds with Keynes’. According to Krugman, a liquidity trap occurs when the proper rate of interest for market clearing falls negative, which the central bank cannot produce as it is limited by the zero-lower bound. Keynes suggested a liquidity trap occurred when investors refused to hold anything other than cash for fear that future increases in the rate would reduce the value of any bond they purchased.

Neither of these hypotheses, nor Dr. De Grauwe’s suggestion of risk aversion explains the current situation, where financial institutions are eagerly buying bonds and making highly speculative (therefore risky) loans.

What highly speculative loans?

Also, short term Treasuries = cash right now. It’s just a savings account to keep liquid cash. Even though rates are 0 and thus there’s only one direction to go for rates and prices of bonds, there’s little room for the prices to swing in the shorter term bills and they’re good as cash. That’s why rates have been driven down to zero because they’re viewed as cash equivalents.

But you’ve hit on perhaps why banks do not wish to expand credit (create loans). You write:

With rates this low, any loan assets created would seem overvalued and perhaps that’s why there’s little demand for them or willingness by banks to supply them?

So investors _are_ holding cash (and equivalents like Treasuries at ZLB) and there isn’t a lot of willingness shown for non-cash normal bonds.

I don’t know what speculative loan activity you’re talking about (if you could be more specific?) outside credit given to play in the stock market/other asset markets or to corp clients.

Banks play heavily in the OTC derivatives markets, carry trade, real estate etc. They just aren’t making loans into the real economy.

As for bonds = reserves, this is true in a fixed exchange system but not in a floating exchange where reserves are highly limited in utility. Reserves are every bit as safe as government securities; the reason demand for those securities is high is that they pay out more interest than reserves and are fungible, where reserves are not. An investor can buy things with Treasurys.

“Reserves cannot become part of the money in circulation. They live on hard drives at the Fed”

Reserves are vault cash + reserve balances (deposits) held at the Fed. Reserve balances are just ‘vault cash in electronic form’.

Reserves can become part of the money in circulation. They simply have to be withdrawn as cash.

Reserves can become part of the money in circulation. They simply have to be withdrawn as cash. jm

True but then they are not reserves!

Btw, we need a risk-free fiat storage and transaction service so we can abolish deposit insurance for the banks and put an end to their government-subsidized counterfeiting. That service should make no loans, pay no interest and be free up to normal household limits.

If people wish to risk their money then fine but at least give them a real choice not to! And no, the mattress is no real choice.

More details on F. Beard’s type scheme:

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2010/11/modern-monetary-theory-there-is-another.html

Mansoor H. Khan

“True but then they are not reserves!”

That’s like saying “money in my pocket can never become money in circulation – because then it wouldn’t be money in my pocket!!!”

Some people have this idea that “reserves” are strange things that are somehow mysteriously stuck inside the Fed (locked on the Fed’s hard-drives), and can’t get out in any way.

No, they’re just cash and they can be taken out as cash.

private banks as they are able to leverage (pyramid) up to 10 or more times the government created money or deleverage and destroy money

——————–

That’s not how bank credit is created, not by pyramid on base.

That’s like saying “money in my pocket can never become money in circulation – because then it wouldn’t be money in my pocket!!!” jm

Not quite. Cash outside the banking system is cash the banks can’t leverage.

However, a 100% reserve requirement would make reserves and cash in circulation equivalent.

Let’s see … when is a tax not a tax? Oh yeah … when it is inflation.

Talking about no representation.

Oh the hubris of it all.

It is a shame that CB’s aren’t just clearing houses. An lament ode to the financial system’s highways and byways being toll roads and not treated as the monopoly they are.

I’d prefer a little micro applied to the macro. I so envy is not cured by magical liquidity.

iPhone autocorrect

It is a shame that insolvency is not cured by magical liquidity

It could be and, eventually, probably will be. Money is not what it was–it is, like the human brain, infinitely plastic and can be defined and redefined by central bankers working in concert which they are beginning to do.

Those who rationlize institutionalized theft such as De Grauwe are social wreckers, lending a hand to bail the banksters and scourge the poor. ‘Progressive,’ ain’t it?

the only point De Grauwe made is that central banks can’t go broke, and that fixing banks’ balance sheets doesn’t automatically cause inflation in the real economy.

If banks were “spurred” to create another housing bubble, by lending again to consumers, then housing prices would presumably rise — asset inflation, securitized mortgage assets would re-inflate.

The problem remains of the gap between consumer income vs debt obligations.

The ethical purpose for money, recognized for a long time, including by Lysander Spooner on Mises, is mainly COMMERCE and FLOW. The austerity trip is that money should have a static value or grow in value, while the real economy deflates — but THAT is will known to cause waves of bankruptcy and foreclosure.

The history of the Populist movement in the US around bimetalism and William Jennings Bryan, this was pushing for inflation of the money supply in the false context of commodity metal “fixed” money. Farmers and small manufacturers and retailers — the 99% of that era — preferred inflation because they HAD little savings, they had LAND and other assets. But that 99% had something else — DEBTS taken out to expand farming and other commerce.

Deflation during sharp Recession — now likened by Austrians to a gradual fall in computer CPUs and memory over time — meant that producers and traders were unable to sell their product for enough money to pay their debts and investments, because of periodic collapses of credit markets — so the difference btw deflation vs inflation meant the difference between solvency vs bankruptcy and losing the farm.

Q: Classical liberals like Adam Smith and T. Jefferson, did they see primacy in Capital and Capitalists or farmers and producers?

A: The latter. Lincoln said the same thing, the source of capital is Labor.

This was apparently widely known.

Now, Neoliberalism says the SOURCE of Labor is Capital, so speculators and corporate raiders are praised for “creating jobs”.

Gary,

Bankers and the creditor class rules the world. Their first priority is to keep the usurious system in place. Their second priority is social stability and promotion of general welfare of society.

That is why Bankers and the creditor class keeps humanity stupid about money, banking and economics.

This problem can only be solved by “enlightenment” of the general population with respect to economics (by the way of Veblen, Keynes and Clifford H. Douglas and other with similar ideas).

more at:

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2011/11/here-is-how-bankers-game-works.html

Mansoor H. Khan

A new definition of solvency using the discredited theory of efficient market? Even if the EMH wasn’t discredited the new definition would make it impossible for any company to ever become insolvent….

Economists :-D

“Returning to our example of an ECB purchase of €1 billion of Spanish government bonds, consider a Spanish defaults on these bonds.

• The Spanish government would stop paying €40 million to the ECB.”

In the absence of a true union (no fiscal union etc.), the issue of OMT and default is not the interest payment.

It is that the taxpayers in the country with OMT are absolved from repaying that 1 billion, whereas the taxpayers in the country without OMT do have to pay taxes to repay 1 billion.

The eurozone has vastly different rates of income taxes, not just the percentages, but also the income at which the rates kick-in. Some countries in the eurozone have a taxation of savings accounts. Etc.

Countries with not only low tax rates for the very wealthy, but also lots of loopholes, and lots of tax evasion are absolved by the OMT. Countries with proper tax collection systems and very high rates, even for the average wage earners, need to continu taking money from their people.

I think this is covered by De Grauwe just after your quite, when he writes that “at the moment of the bond buying programme interest bearing debt is transformed into monetary liabilities of the ECB (money base)” leading to the possibility of inflation. So if I understand correctly the billion is generated by printing cash or whatever is electronically equivalent, with no liabilities to the taxpayer in the case of default, except for the risk of inflation.

Ruben,

It is not covered by De Grauwe.

He writes: • It is literally true that the central bank could put the government bonds ‘into the shredding machine’; nothing would be lost.

Please note that this same argument was made some time ago by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard, regarding the Abenomics of the BoJ: Just let the BoJ buy that 250% debt-to-GDP, and put it in the shredder.

This may be OK for a true union: i.e. 1 country with 1 tax system, like Japan, like US.

The eurozone is completely different. Hence, De Grauwe’s statement that ‘nothing would be lost’ is completely wrong.

What would be lost is the obligation of the Spanish taxpayers to repay that 1 billion.

As the ECB does NOT envisage OMT for the northern countries, the taxpayers there are NOT absolved from their taxburden.

Were the ECB prepared to put equivalent amounts of debt of all eurozone countries in the shredder, then, and only then, does the rest of his article perhaps make sense.

Carol, it seems to me that you don’t get the meaning of the quote of De Grauwe that I isolated for you.

The 1 billion principal in the example is made up from thin air (money creation) and transformed into ECB monetary liabilities by expanding the money base. In the case of default, nobody pays for the principal except through inflation. That’s why De Grauwe is saying that the only loss in the case of default is the loss of pro-rata payments of interest, and possibly some inflation.

In craazyman’s insight, the principal created by the central bank -and this only applies to principals created by central banks- is an assertion of new cooperation that in the case of defautl would not metarialize. it’s money creation that would not turn into real cooperation leading to tangible products.

In the 1 billion example, the 1 billion was an assertion of the ECB of new productive cooperation in Spain, that would yield interest payments to all euro central banks, which in the case of default, would not materialize doing away with the interest payments and dissolving the principal into inflation.

So to me the article makes a lot of sense, especially when read together with craazyman’s remarkable bus-riding insight.

Hi Ruben,

it seems to me we’ re talking past each other.

I was talking about the 1 billion Spanish government bonds.

Money which the Spanish government borrowed from the market, saddling the Spanish taxpayers with the burden to repay.

With OMT you are talking about the 1 billion from the ECB, and you are right: money printing, nobody needs to repay anything. :-)

With OMT the ECB reduces the taxburden for the Spanish taxpayers (by taking that 1 billions of the balance sheet from the Spanish government). The ECB has no intent of reducing the taxburden of people in countries with high taxation rates and lesser evasion. That is a fairness problem in the eurozone which is absent in 1 country.

this is pretty good but if he keeps going he’ll figure it out in abstracto

what always puzzled me is just what the liability is that money represents. it becomes circular at first. it’s a liability in terms of itself, so it’s no liability at all that way.

the break through for me came riding the bus when I realized all money is imaginary and the only reality is cooperation in the physical world.

there are three forms of reality — the 1) imaginary wave form realm, which the australian aborigines refer to as “dream time”, 2) the imaginary structure realm, which are the dream forms that organize social group consciousness. Money of course is part of this, as to some extent are emotions and Jungian pyschological archetypes and Plato’s “forms” and 3) physical reality, which is arms and legs moving around in cooperation or conflict.

Obviously 3 is to quite a large degree a function of 2.

since money is an imaginary structure, a central bank can’t “run out” of it any more than a person can run out of their imagination.

but society can run out of cooperation and break down. here of course is the reality of the limit on central bank money creation and the liability that money represents and the asset the liability offsets.

the asset is social cooeration in general and the liability that each unit of money represents is a share of that cooperation. cooperation here is somewhat analogous to “beta” in the parlance of modern portfolio theory, although the parallel is not excact.

inflation is used as a proxy or a breakdown in cooperation, since it’s mathematically measurable and “cooperation” is not mathematically measurable and is somewhat subjective.

consider an addict of some sort, like an alcoholic. If they want a drink and you refuse, you are not “cooperating” with them, even though they likely pay you 20 dollars at the time. If they could actualize their utility in a transaction, the price of drinks woud rise to 20. Of course, a year later, when they’re sober, they look back and say they would have gladly paid 30 not to have had the drink. so what would the drink have been worth to them?

therefore prices are inherently time indeterminate and inflation is an indeterminate measure of cooperation, but it’s a somewhat useful proxy for it.

the central bank can create money if the existnce of that money activates latent cooperation potential into actual cooperation. as long as the increase in cooperation equals or exceeds the increse in money, the effect is beneficia.

inflatin would be when the increase in cooperation is slower than the increase in money, therefore it’s considered bad. but since prices are time indeterminate, one can’t say that inflation is absolutely bad,m only relatively for some parties and not for others.

it gets abstract if you keep going

Sign me in to your bus-riding epiphany but you write too much (albeit interestingly). Inflation is the potential increase in the cost of cooperation due to expansion of the imaginary money base, as in the barman/woman willingness to cooperate with you by preparing a margarita for your consumption but for a higher share of the product of your other cooperative efforts than earlier.

craazyman,

You are on the right track:

“only reality is cooperation in the physical world.”

Money is a social arrangement involving laws, people and productive capacity of the economy and people’s trust and confidence in the currency issuer. If the public does not use a particular currency it cannot work and will be abandoned.

All social arrangements are complex and abstract (they cannot be touched) but they are real. Not just atomic things (things) are real. But relationships are real too and have real consequences in the physical world around us.

Double Entry Accounting (Assets = Liabilities + Owner’s Equity) is a useful tool to manage reality and our economic affairs and our economic relationships.

We should not let the tool (Double Entry Accounting) manage us!

Fed balance sheet is very simple:

Asset Account (left side of the balance sheet) = Social Capital

Liability Account (right side of the balance sheet) = Monetary Units (i.e., FRNs issued).

Debit Social Capital

Credit FRNs issued

More at:

http://aquinums-razor.blogspot.com/2011/02/give-500-per-month-to-each-us-citizen.html

Mansoor H. Khan

Thanks Craazy. You’ve just given me a definition of inflation I can understand: “… inflation is used as a proxy for cooperation… and it is a time-indeterminate measure of cooperation.”

… and then you made me think this: Money isn’t a liability, it is liability insurance. It is risk insurance against non-cooperation. See what you started?

that’s exactly right. consider a tribe 10,000 years ago. initiaally people cooperated based on human need and instinct. as it got bigger and more numerous, confusion arose because more than one person could do many things. who should you do the with? who should you procreate with, in particular? but not exclusively

so they invented castes and clans and elaborate ornate totems and taboos to organize how the individuals were to interact. these are elaborate states of imagnation structures that regulated how individuals interacted.

you were secure if you abided by the complex structures of imagination, if you went agains them, some priest kicked yer butt if not strung you up

afgter a few thousands years this got to be a bit too much because people didn’t want to be hemed in like that. so they took all that complex energy that regulated everything — that regulated the life force of the group — and they created this metaphor for it called “money”. If you have it they’ll cooperate with you now, but if you don’t, ferget it.

it’s as imaginary as clans, totems, taboos, but it’s soething that accelerates the achievement of individuated consciousess fro that comunal mind.

julian Jaynes, the big drinker, speaks a little about this in his big book I don’t know how he wrote it but he did. Money is a creation of social imagination that enables inviduals to interact in ways that advance social cooperation and it acelerates the achievment of individuation but it doesn’t guarantee you’ll do the right think when you get there.

but it’s soemthing that helps people see the right thing, oddly enough, to see beyond the walls of totem and taboo and clan and caste into a universality.

eventually there will ahve to be a transcendence of money, and human action will be based on a perception of spiritual presence and intention perceived directly with the mind, but consciousness isn’t there yet, except among the best of the best of the best, or the wackos.

sorry about the typos. just got ain ipdad and the keyboard is kiind of small. it really makes it hard. :)

there’s no mouse so you have to keep f*king with the screen with your hand all the time.

I don’t like this thing very much. I’ll probably take it back. why waste time like this when I could be staring out a window doing nothing or eating a hot dog. hahahaha

Or gardening while drinking a martini!

Yup, that’s Keynes’s liquidity preference theory of value.

money value tracks the odds of future cooperation.

he lost me at ‘efficient markets’, but when the incentives

of future cooperation are moved forward (and vacuumed

up by the 1% via levered plays on that future promise),

eventually the future cannot be put off any longer

an incentive-sapped future finally arrives, and unsurprisingly,

it ‘sucks’ (pun intended)

of course, according to this ‘economist’ (derogitory term yet?)

zimbabwe and argentia did not happen, since they had

their own currency

linear thinker fails at non-linear analysis

wake me up when you can find an economist worth two bits

what always puzzled me is just what the liability is that money represents. it becomes circular at first. it’s a liability in terms of itself, so it’s no liability at all that way.

No, government base money is not “a liability in terms of itself”. It is a very ordinary sort of liability, that all children understand. That’s the problem. Monetary economics is so simple, so easy that everyone understands it, but they don’t understand they understand it, and they invent transgressive hermeneutical non-linear complex quantum chaotic theories to explain something very simple.

Government money is a liability, a debt, just like a theater ticket is a liability of the theater for a performance, or whatever else the ticket-holder and theater-owner agree it can be used for. People confuse themselves by thinking that money is a liability for something else, either somebody else’s money or something non-monetary.

The government sells a lot of stuff. (Particularly the immaterial right to performed taxed activities). The coupons the government issues to buy stuff from the government, to pay, redeem, resolve, cancel debts to the government are called dollar bills, which are a debt the government owes the holder. Just like a theater ticket represents a debt the owner owes the holder, and is cancellable against a debt the holder owes the owner. That’s all.

Bullshit about bonds and interest rates is just the theater owner offering 11 tickets for tomorrow’s showing in return for 10 tickets for today’s, when he is doing minor renovations maybe.

Your points about cooperation are very good. Cooperation is the division of labor. And as Geoffrey Gardiner (a master of all trades according to Randall Wray) lucidly points out the division of labor, cooperation is simply, logically impossible without the relation of debt between the two cooperators. Money is just debt writ large, a whole society cooperating, dividing its labor. GG was probably riding buses earlier than you, before any of us here were born. :-)

SO, if I buy a 30-year bond and interest rates from 3% to 6%, the value of my bond would go down 30-50%, if I wanted to sell it.

The only way Bernanke would not lose money is if he does not sell any of the bonds and MBS he has been buying. If there is a default and some of these decline in value, he will just “print” to make up the loss and break even?

TAX HAVENS

The Institute For Policy Studies new report on tax havens is awesome.

59 companies had $544 billion in U.S. profits at he end of 2012. They are holding offshore $1700-2000 Billion in “profits” much of which was gained in U.S. Sales. All taxes paid elsewhere are deducted from U.S. Obligations.

General Electric has 38B from 108B of income. Honeywell had a 43% increase to 11,6B in 2012.

If they return these profits to the U.S. They would not pay $544 Billion but US Tax Rate on it.

That would help but only dent the 700B Deficit . In 2010, corporations paid a 12..5% Tax Rate.

The firms say if they do return it then it would be used for job creation . Dream on!

http://Www.ips-dc.org/globaleconomy

Now it becomes more clear that desperation is paramount, gambling is necessity, and the author is exceeding the amount of medicine and other substances ingested for stable function. The rationalizations for the destruction of the monetary base and safety for those poor fools among us that must conserve is frightening. They author appears to state that a tumor would be appropriate growth.

according to the author, there is no phase change

from benign to malignant

Here the Fed has expanded its balance sheet by buying assets (MBS), therefore expanding the monetary base, and the banks are hoarding like mad, which keeps M3 from growing – but it does serve to build the banks’ reserve capital. So there is no inflation and the economy is in the doldrums at best. Not sure why this is considered effective. Except to save the banks. It just aggravates the deficit. If money were spent directly into the economy things would improve faster. Looks like bank hoarding is stealth austerity.

Economists are going to be swinging from nooses when all is said and done, right alongside the politicians.

seigniorage in the age of legal tender = extortion

This creates massive moral hazard.

This, on top of not jailing anyone, is the mother of all moral hazard.

Should’ve jailed people, then we might be able to get away with this…

We have to see this article in a wider context. Central banks these days need to be “credibly irresponible” (Krugman). Therefore it is important to buy the crappiest assets you can find, unlimited amounts of them, and when they blow up they will not be replaced by some quality stuff. If a central bank has quality assets on its balance sheet it is in a position to reverse provision of base money by selling these assets. This would look sort of responsible and is therefore a no-go in this policy frame work. Also lucky for the ECB there are plenty of crappy assets for sale in Europe.

To really understand why this makes sense you need to believe that inflation comes from inflation expectations as most Neo-Keynesians do. This is in a way the phlogiston theory of modern economics: if you can’t explain some phenomenon like inflation properly, you just add a variable that cannot be quantitatively observed in real life and there you go.

So to increase inflation (say to 4%) you need to “unhinge” inflation expectations. And this you achieve by crazy monetary policy. Finally there goes the dreaded zero-lower-bound. I think this is what de Grauwe is really aiming at.

The consequences of insufficiently irresponsible monetary policy are currently put on diplay in Japan.

If all this doesn’t work the next step towards “credible irresponsibility” will need to be more radical. Therefore I would like to claim ownership for the proposal to replace Mr. Draghi by a guinea pig here and now in order to secure my place in the hall of fame of economics.

if you unhinge inflation expectations

in a declining wage, difficult employment

environment, you get the opposite of

what you think….people will increase

savings. and decrease discretionary spending

under those conditions — this is exactly why the

fed has been failing

in actuality the fed would be better off raising rates

to support the economy, but they cannot because

it would hurt the banks…. and policy is currently

all about supporting the banks

one should not ignore preconditions when attempting

to play central planner uber god

It is amazing how one economist after the other is unable to understand inflation correctly. The idea to simply focus on cpi for measuring inflation is the real defect in their theories.

We devalue currencies the world over since many decades. This manipulation of our measure of wealth has not been lost on the population but has produced a corresponding change of behaviour. Less and lesser people keep their savings in form of currency but use the currency simply for a transaction from one tangible asset to another. The longterm implication of this behavioural change is at the core of today’s worldwide crisis as it led to bubbles in those tangibles.

So before creating theories about central banking an economist should start to understand the true longterm implications of inflationary monetary policy on society. Without the deeper understanding of this aspect, an analysis is simply another way of justifying further manipulation of society.

Aren’t we all happy to serve as the lab rats at the service of some indoctrinated artist of manipulation?

Not this idiot DeGrauwe again with his ‘central banks have unlimited ammunition’ mantra.

The current system has never been sustainable, its just that 60 years of ‘perpetual growth’ (fuelled by population increase) have deluded many into thinking that ‘growth’ can be maintained forever, and it cannot.

Ordinary people would be better off without central banks since all they’ve done the last four years is bail out the rich at our expense and inflate massive bubbles all over the place.

Simple rule: all bubbles eventually burst. If the economic system depends on perpetual bubbles and cannot survive if asset prices (housing, stock) decline to a normal level then the system isn’t sustainable.

No fiscal transfers, ever. No fiscal union. Period.

There is too too too much brain energy and propaganda spent on ‘how finance works’ and not much at all as to how ‘the real economy works’.

Simply put, finance is NOT working.

Hence all finance solely focused debates are a waste of brain energy

To say central banks have no solvency issue is a linguistic trick – it’s wordplay. Yves and other Neo-keynsians beleive that that — technically — a CB cannot be “insolvent” because it can always print more money to meet obligations. Of course, if creditors refuse to accept the CB’s fiat funny-money, the whole Keynesian sand castle collapses. Functional insolvency results.

Very Good article, but De Grauwe & Kervick above can be misleading at one point. There definitely is a very important sense in which the Treasury backs the Central Bank.(Need I say, according to MMT?) And it should be made clearer than De Grauwe’s statements:

• The central bank (that cannot default) needs no fiscal backing from the government (who can default).

The central bank can default, the same way the government or anybody else can: by deciding to default.

• The only backing the central bank needs from the government is that it can keep its monopoly power to issue money in the territory over which the sovereign has jurisdiction.

The central bank DOES NOT have a monopoly on issuing money. Any bank has this power. In fact as Minsky said, anybody has this power. (Unlimited) Money issuance is not a miraculous power, but an everyday occurrence. Whoop de doo.

If you treat the Central Bank as part of the government, it can be considered as the issuer of the government’s money. But if you do not, which is confusedly the more usual practice, then the Central Bank is just another bank, which is backed by the government, not vice versa. In any case, the Central Bank is basically restricted to monetary (exchanging one form of government debt for another) which by its nature is obviously much less important than fiscal (indebting the government & redeeming government debt through taxation).

The power that the Central Bank has is that the money it issues (in a highly restricted fashion) can be used to pay taxes with immediately. That is, reserves, FR notes are made equivalent to US notes, to matured Treasury bonds, which are direct debt obligations of the government. (We are still pretending that the CB & the Gov are different). The T-bonds (deferred tax credits) back the FR notes, not vice versa. FR notes are valuable because you can get T-bonds for them, not vice versa.

The analysis of the Euro is very interesting. But in the above schema, Germany & everybody else are very different. The other Eurostates are like US states, while Germany is more like Uncle Sam. The ECB can backstop others’ bonds, while Germany backstops the ECB. If Germany left, its currency would skyrocket, while the others would drop.

In other words the central bank makes a promise of price stability. That’s all. A promise which it has no power to keep. What it does to sometimes restrain inflation – raising rates – generally feeds inflation rather than fights it. The government can stabilize prices, not the CB, whose main function is to convince people it has a function. Oh, and make some rich people richer, by usually doing the opposite of what a 10 year old could see that society, the real economy obviously needs.

@ Anonymous

“The central bank DOES NOT have a monopoly on issuing money. Any bank has this power.”

Basel Regulation produces the guide lines for the banks in terms of leverage and capital requirements. These guide lines and regulations are the result of central banks’ decisions.

So please do not give us a misleading statement as if there is no authority responsible for the extent at which banks can use leverage resp. create money.

I am slowly sick and tired to hear that the financial crisis was an unforeseeable storm like a hurricane and that no one can be made responsible.

this article is not economics or even finance.

it is about the legal foundations of fiat money.

therefore it is about politics.

As a government can legislate whatever it wants (one US state legislated away sea level rise because that was inconvenient to beach property developers – a major source of “free money” speculation in the US).

the question then should be “what if” the govt produces as much money as it can without constraints.

the rules of banking and fiat based central banks were created for some reason.

it is annoying to see powerful people again and again repeating that modern money is just electronic records created at a computer. Yes it is, but it is more than that.

Just like a human being is water and proteins and calcium, but something more than that as well.

You cannot ignore the function of money in the political economy and concentrate purely on the technical aspect of how money is implemented (the quintessential “what vs how” of engineering), and claim that you have violated some basic law of physics.

The essence of money is trust, or faith. Faith is is a human attribute, not a technical one. If the producer of money starts to pretend there is no constraint at all on it, then the faith will evaporate very quickly indeed. This is really the reason that trillions of dollars produced by the Fed have been confined to asset markets, as if they leak into the real economy there would be havoc.

It has happened many many times in the past.

The “current liquidity-trap setting” is perspective conveniently ignoring the current insolvency setting driven by a failed, securities-based “banking” system sustained by Ponzi finance facilitated through the explosion of derivatives whose parabolic growth depended on implicit guarantees that are now explicit, and in so becoming find lenders of last resort with no backstop, thus defying insane efforts by foolish LSE monetarists to restore confidence through arrangements assuredly minimizing the risk of a systemically threatening default. There is no such possible arrangement available in fact. Indeed, now that the GSEs no longer can play “shadow Fed” and the Fed, itself, has been forced to commit to the impossible–sustain a rotten [shadow] banking system’s infinite multiplier–the role of “hot money” required to forestall currency collapse is now reached the point where one of the only two possibilities forward in fact is being hastened–hyperinflationary blowout or deflationary collapse. There simply is no middle ground. Yet we still see charlatans from the stable of oligarchical interests whose decades-running aim has been the destruction of sovereign nation states (with the U.S. being at the top of the list) inviting all to commit suicide promoting schemes with a sophistry whose “enticing” aim those rational view but the last gasp of fantasy’s promotion venturing to freeze from the necessary, politically facilitated reorganization, the absolute majority whose wealth otherwise is at the precipice of its destruction.