By David Llewellyn-Smith, founding publisher and former editor-in-chief of The Diplomat magazine, now the Asia Pacific’s leading geo-politics website. Originally posted at MacroBusiness

That is the question today. Let’s first ask markets. The one outstanding difference between the current global market sell-off and other “risk-off” episodes is that US Treasuries are not especially bid. Ten and thirty year yields have not budged for two days as equities and emerging market currencies have been monstered. The following chart from BofAML captures the divergence:

There are no slowing taper fears here, which is especially marked since US data has been ordinary. Last night’s crucial new home sales were weak, via Calculated Risk:

Sales of new single-family houses in December 2013 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 414,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 7.0 percent below the revised November rate of 445,000, but is 4.5 percent above the December 2012 estimate of 396,000.An estimated 428,000 new homes were sold in 2013. This is 16.4 percent above the 2012 figure of 368,000.

The US bond market retains its faith in taper.

However, to make things interesting and confuse a little, the US dollar has been weak and gold firm since the weak China Flash PMI kicked these dynamics off, suggesting a slowing taper:

Let’s take this at face value and conclude that markets are as yet undecided.

So, let’s consider the possible channels of contagion that could see China slow the Fed down. There are four.

The first is the trade channel. The US exports roughly US$150 billion of goods to China per annum out of total of approximately $700 billion in merchandise exports. That’s not much in a $16 trillion economy so any slowdown is unlikely to be large enough to slow growth materially. Besides, the Chinese rebalancing should actually increase its imports over time as it boosts consumption.

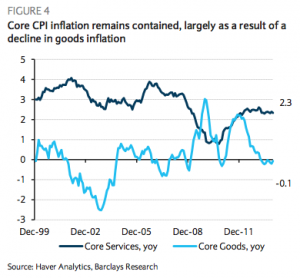

The second channel is more significant. The US imports about $500 billion in Chinese goods per annum. And if they are falling in price because China is slowing and commodity prices are falling then that’s a material disinflationary pulse into the US economy. As I’ve illustrated before, goods are where US inflation is at its most weak:

I expect Chinese inflation to remain weak and commodity prices to fall further so this is definitely a potential channel of taper slowing if inflation falls below the Fed’s comfort zone.

The third channel is China’s impact on global bond prices. The Chinese rebalancing should lead (over time) to capital account liberalisation and considerably lower current account surpluses. In that event China will by definition be recycling fewer surpluses into foreign market investment including US Treasuries. That will see upwards pressure on yields without the Fed doing anything, though this likely a long term influence more than an immediate issue.

The fourth channel of influence is markets themselves. Will Chinese slowing infect forex and credit market stability enough that the Fed might feel contagion risk warranted slowing taper? JPMorgan asks the question:

The past two weeks have presented surprises from almost ever corner – undershoots on Chinese activity data; stress in Chinese credit/money markets; idiosyncratic developments in Russia, Turkey and Argentina; data wobbles in the US – but only the China ones meet the criteria for potentially being systemic for FX because the underlying issue is opaque and large-scale. By comparison, it is a stretch to say that the US is slowing meaningful and durably. It would also be difficult for other EMs, somewhat large as they are, to contaminate global currency markets because they lack the trade linkages to other economies.

But an issue which is opaque and large isn’t always worthy of a prolonged vol shock. (Recall all unfulfilled anxieties around the US municipal bond market post- Lehman). The situation is serious, but for that reason deserves proper context. JPM’s long-standing view has been that the Chinese authorities would continue a process of credit tapering to reduce China’s indebtedness from extraordinary levels (chart 4), and that such a process would deliver the weakest growth (ex the Lehman aftermath) in about 15 years (7.4% real GDP growth in 2014). Combined with interest rate liberalisation, tapering will also deliver higher rate volatility and possibly higher lending rates; hence the recurring spikes in Shibor such as those in June and December 2013 and in January 2014. The resulting tightening could lead to a rise in non-performing loans and defaults, such as the possible one which arose this week with a trust loan product (see Greater China Quarterly Issues, Haibin Zhu, Grace Ng and Lu Jiang, January 24).

So far, so grim. At a minimum, the baseline should be subtrend Chinese growth for another year, and it seems silly to speak of a Chinese growth upturn in 2014 as the G-4 economies lift. This outlook has anchored our long-standing negative view on China-sensitive currencies such as AUD/USD and Southeast Asia. USD/CNH is a different animal given China’s still strong balance of payments profile; we still think it ends the year around 5.95.

But sub-trend China growth alone doesn’t justify meaningfully higher volatility and trend strength in JPY and CHF. That market outcome requires a more extreme deceleration in Chinese growth to perhaps 6% and/or widespread defaults across the various credit sectors always

under scrutiny. These include trust loan products sold to high-net worth individuals, wealth management products sold to retail and local government debt. We still think the authorities are targeting a growth floor closer to 7% than to 6%, and that they possess the control mechanisms to allow

selective defaults rather than contagious ones. Hence our reluctance to see this month’s events as the early-stage equivalent of the US sub-prime crisis or Europe’s peripheral debt crisis, two events which were powerfully bullish for volatility, the yen and the Swiss franc. This week we take profits tactically on long GBP/JPY and buy CHF/SEK, but more to reflect short-term deleveraging over the next couple of weeks while Chinese credit market settle and US activity data consolidate.

This argument is right in principle, I think, but the levels are wrong. If China is to slow at all below 7% growth this year (let alone 6%) then global FX and credit market volatility will rise further. I don’t mean there’ll be a seizure, that would take a meltdown in Chinese shadow banking, but I do mean markets reverse some of their confidence in the 2014 global recovery. That will be enough to slow the Fed down as the incipient sell down in US stocks becomes a nasty correction.

I expect the Fed to proceed for now but if China does not pour forth further stimulus then taper will get more difficult with each passing month.

A few points. I’m postponing my judgement on Dec data after we see Jan/Feb ones, to see how much impact the weather had.

Re stock market correction – I believe that Fed would not care that much even by stock market going down a lot as long as the credit markets don’t melt too. In fact, they may welcome the correction as I suspect one of the reasons for taper was to (try to) avoid blaming Bernanke for taking away the punch bowl and stoking another bubble ala Greenspan (if the market corrects due to taper, he can say “see, I didn’t stoke bubbles, I pierced them”), and Dec was his last chance to do so.

As long as EM don’t blast US banks too much (and I suspect the exposure to EM is now concentrated elsewhere then US banks, who have been keen to onsell the exposure in the last year or so), I don’t think Fed would even care too much about EM meltdown.

What not that many people realise is that US is a bit of a trade paradox. At one hand, it’s still the largest trader in the world, but at the same time it’s almost an autarky. US trade/gdp ratio is 24%, one of the lowest in the world, . For comparison, partially embargoed Syria has 16%, UK has about 50%, Germany 75%. And that 24% is historical figure (2012), which is now likely to be less due to dropping oil/gas imports. (as an aside, Japan is not dissimilar in this, with trade/gdp being about 28%, but they import bugger all except for energy to consule locally)

I agree it’s not tomorrow, but I believe a hard landing is where this ultimately goes.

Do people actually read this kind of thing for information?

It was bankspeak. Especially Dimon’s excerpt. Where is the discussion that penetrates the opacity? Like that China is choking on exhaust fumes and has begun to ban cars in Beijing and Shanghai (maybe) and therefore auto sales will fall off a cliff and therefore automakers in Germany and Japan will cut back drastically and maybe liquidate themselves. And therefore GDP in those two countries will plummet. And in the US as well. And a huge traditional driver of economies will be gone and nobody has anything to replace it with, etc. I could care less about the number crunching speeches by self-interested banksters who think they can financialize any misstep – maybe they can, but their information becomes so useless it makes them useless.

Yes, welcome to the blog.

Based on past experience, my own very simplistic view is, if US equity prices fall more than 15-20%, the taper is off. Trickle-down is the ONLY thing the Fed knows.

I’d love to be proven wrong.

Since there are so few comments, I will expand mine:

First, I think the idea that Chinese growth dropping below 6% or 5% or 4% for a few years, then back off again to below 3% and keep it there is the best thing China could do for itself. This bizarre assumption that China will explode socially at lower levels of growth is a good example of a typical Western foible: seize on the construct that best suits “us” (as defined by giant US corporations) even while maintaining it’s the best advice for “them”, then relentlessly flog it to the most Westernized Chinese in and out of China until it is “factualized”.

I believe Chinese society is far, far more resilient than that, and with the creation of an adequate safety net (basic income if unemployed, pensions, health care) could readily accommodate a much more thoughtful pace of development – perhaps even take a decade or so to address mammoth environmental issues. Even without a net, though, most Chinese would accept the need to slow down if presented the arguments for that necessity in a calm, open, frank manner.

They’ve done well to dial down this far. Now, if they can repeat that performance and tune out cries of “stimulate” from a West which refuses to get its own act together on any front, they just might avoid a hard landing. However, I believe the positive feedback produced by a slowing China (and others) combined with gravity’s pull on the US stock market is likely to cause policy errors on both sides of the Pacific, i.e., by hitting the gas again.

China won’t of itself cause an end to “taper”, but Yellen will not make it to zero QE.

I’ll expand on mine, too, just for kicks — and it may seen I avoided the question.

I have no idea if China will cause the US markets to go down 15-20%. I have no idea what the US markets are going to do in the short term or even the intermediate term. It’s empowering, or freeing, to admit that to myself — I can do other things, like read a good book.

(Right now I’m reading the “autobiography” of MLK, compiled and edited by Clayborne Carson. It’s superb, and it draws a portrait of a profound and noble man.)

Greatest man in my lifetime and in my view greatest American ever.

Prediction of year 2014. QE will be at 100-120 billion per month by end of the year.