Anyone in the political or public relations game knows that the best way to make a disclosure but minimize its impact is to do so on day before the long holiday weekend.

If the government had the ability to make an announcement they’d rather not make during a major holiday break, they would. And the New York Times, which does have that luxury, looks to have done precisely that with an important article on private equity fee abuses by Pulitzer Prize winning reporter Gretchen Morgenson. As we’ll see shortly, this isn’t one of her 1000 or so word weekly “Fair Game” columns; this is substantial piece of original reporting discussing several types of private equity fee abuses.

So why would the Grey Lady bury an important article by running it on long weekend? Oh, and worse, that has anodyne headline, “The Deal’s Done. But Not the Fees,” which doesn’t flag who the perps are? One has to assume that the Times isn’t too keen about rocking the boat with powerful financiers, particularly since the incoming New York Times editor, Dean Baquet, who has a track record of avoiding controversial reporting. In addition, former Lehman Brothers partner and art world denizen Michael M. Thomas dates the beginning of the end of the New York Times as a journalistic institution from when Punch Sulzberger joined the board of the Metropolitan Museum. As Thomas remarked, “He needed to be dining with people he should be dining on.”

Make no bones about it, the Morgenson story, which comes on the heels of a Wall Street Journal exposing industry leader KKR’s far too clever and potentially impermissible dealings with its house consulting firm, KKR Capstone, discloses important new fee abuses, including getting paid for services never rendered.

One of the things that the broader public may not realize is that the normally complacent investors in these funds, known as limited partners, have been pushing back against the fees charged to them by the private equity firms, who in industry parlance are called general partners. Thus this fee chicanery is particularly important because it reveals a concerted effort by the general partners to out-fox the limited partners and continue to extract more in rents from the limited partners than they think is warranted and thought they had agreed to pay. It’s an up-market version of Elizabeth Warren’s famed “tricks and traps.” . From the Morgenson story:

“In some instances, investors’ pockets are being picked,” Andrew J. Bowden, director of the S.E.C.’s office of compliance inspections and examinations, said in a recent interview. “These investors may be sophisticated and they may be capable of protecting themselves, but much of what we’re uncovering is undetectable by even the most sophisticated investor.”

Actually, what Bowden is suggesting is worse than Warren’s objections to sneaky hidden terms in impenetrable consumer contracts. While Bowden says that the general partners are waging a successful document/deal structuring complexity war against limited partners, his “pockets are being picked” suggests the SEC is also seeing cases of flat-out embezzlement.

The public assumes that the private equity kingpins get rich by virtue of their success fees, the 20% (or more in some cases, typically after a hurdle is met) that they get when their investments show a profit. It is much less widely known that general partners charge a raft of other fees, including transaction fees (which are on top of the fees paid to investment bankers and funding sources) and monitoring fees (which are in addition to the management fees). The exhaustively researched new book Private Equity at Work by Eileen Appelbaum and Rosemary Batt explains where the general partners’ income really comes from:

The conventional understanding is that general partners have earned about two-thirds of their compensation from carried interest [the upside fees] and one-third from fixed components such as fees. At some point that relationship changed. One econometric study of 144 buyout funds from 1993 to 2006 found that almost two-thirds of the revenues of PE firms came from fixed components, but this study did not show how or when the proportion of fixed-to-carry changed over this time period. (p. 254)

Why does this split matter? To the extent that private equity general partners earn their pay from sources that don’t depend on the success of the investment, their incentives are not aligned with those of the limited partners. It may be no surprise that Appelbaum and Batt (consistent with other reports on the industry) find that the shift to “heads I win, tails you lose” fee components took place during a time frame when buyout returns have been declining.

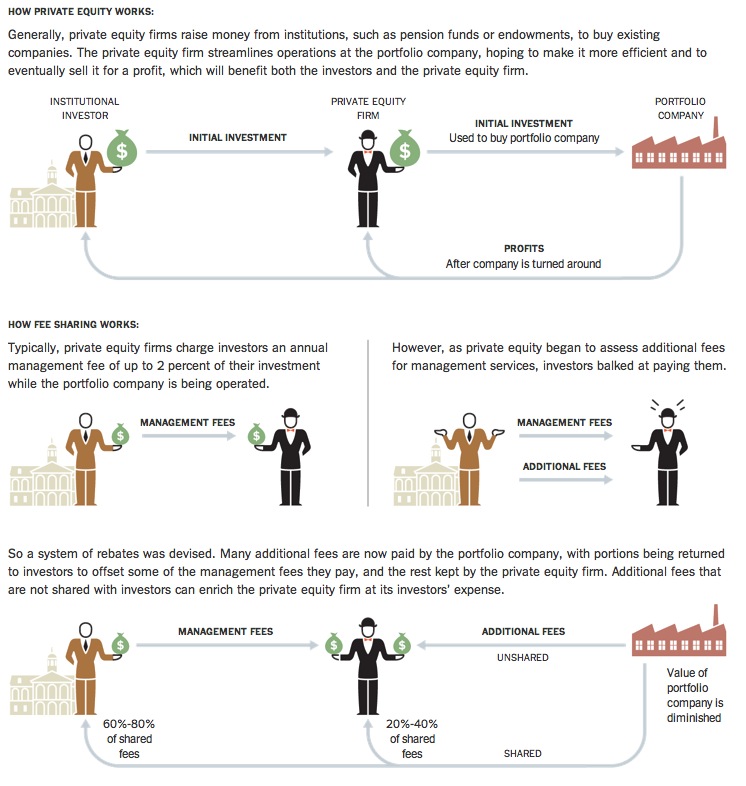

Morgenson explains, as did the Wall Street Journal in its KKR story, the big way that investors have tried pushing back is to have a big chunk of all those extra fees offset against the annual management fee (the 2% of the prototypical “2 and 20” although for bigger funds, the management fee level is lower), via this graphic (click to enlarge):

But this approach of rebates caps how much the limited partners can recoup, as Morgenson notes:

There are two problems with these reimbursements. Because they can offset only the amount an investor pays in management fees, ancillary fees in excess of those payments are not shared; they are kept solely by the private equity firm. And some fund advisers have found ways to limit the amount of fees they must give back.

One example involves senior advisers hired by private equity firms to help oversee acquired companies. These advisers tend to be corporate executives with experience in a particular industry who work with the acquired companies; a former hotel executive might work with a portfolio of companies in the hospitality business, for instance, to help them run more efficiently.

Traditionally, these executives have been employed directly by the private equity firms, meaning that the firms, not their investors or the portfolio companies, have paid the executives’ salaries, which can be substantial. In other cases, they are paid by portfolio companies, which means that the salaries may be considered a fee to be partially reimbursed to the investors.

Recently, however, some private equity firms have found a way around this. Salaries of executives hired as unaffiliated contractors are not subject to reimbursements, private equity filings show, and by making these people contractors, rather than employees, firms can avoid reimbursing the investors for their costs. The private equity firms also increase profits by shifting the salary of the contractor to the payroll of portfolio companies.

This, readers may realize, is a more general version of the issue with KKR Capstone: limited partners were presented with a management team when the fund was marketed, and assumed all its members were on the payroll of the private equity firm and hence paid for out of its management fee charged. They were unaware that they’d be billed for many of them separately, by having their compensation charged against the income of portfolio companies.

Trust me, this practice is common in the industry. If you go on the website of many PE firms, you’ll see people identified as “senior advisors” who are nevertheless on the “management team” page. The odds are high that many of them were presented in marketing documents as if they were private equity firm members.

Morgenson concurs with this reading and flags one example:

Silver Lake Partners is a huge Silicon Valley private equity firm with $23 billion in assets, including investments in Dell, Groupon and Virtu Financial, the high-frequency trading firm. In a 2014 filing, Silver Lake noted that when it retained “senior advisers, advisers, consultants and other similar professionals who are not employees or affiliates of the adviser,” none of those payments would be reimbursed to fund investors. Silver Lake acknowledges that this creates a conflict with its investors, “because the amounts of these fees and reimbursements may be substantial and the funds and their investors generally do not have an interest in these fees and reimbursements.” Similar language is found in regulatory filings across the industry.

Morgenson identifies an even more dubious fee practice early in her article, that of managing to get paid for services never performed. She discusses the sale of Biomet, a Warsaw, Indiana- based company sold by a Blackstone-led consortium for $13.4 billion, which included a $2 billion profit. But the carried interest and the transaction fees weren’t all the general partners got out of this deal:

But for Blackstone and the other private-equity partnerships in the deal — overseen by Goldman Sachs, Kohlberg Kravis Roberts and TPG Capital — this deal will be a gift that keeps giving. That’s because, beyond the profits they share with their clients, they will be paid millions more in fees — for work that they are never going to do.

In addition to a 20 percent share of gains from the sale, as well as management fees of 1.5 percent to 2 percent charged to investors, the private equity firms will also share in an estimated $30 million in “monitoring fees.” These fees were to be charged through 2017, but given that the deal is expected to close early next year, Blackstone, Goldman Sachs, K.K.R. and TPG will be paid for two years of services that Biomet isn’t receiving.

The SEC and the media have only started peeling the many layers of the onion of private equity firm exploitation of too-trusting (and even when not that trusting, outmatched) limited partners. You’ll be reading more about these abuses in the coming weeks and months. Pass the popcorn.

Why do I feel like this is just another page in the ongoing book of world propaganda writ large? I am getting tired of popcorn already!

Just because wink, wink, nod, nod is no longer working correctly at some higher levels couldn’t mean that the disease we have is systemic, could it?

Fie! When is Gaia going to come along and kick us in the nuts? Didn’t I say I was tired of popcorn already….?

A case of outrage fatigue? Me too. But in this case, it’s good to see tyrannosaurus dining on velociraptor instead of human beings, aka Muppets. Predators turning on each other may signal a tipping point.

Unless your pension fund is an investor, in which case you are the meal, not the velociraptor.

(Moved your comment.)

You’ve got this wrong. They are preying on you.

25% of the $3.5 trillion in industry assets comes from public pension funds, as in the pension funds of municipal employees like cops, firemen, and bus drivers, and state employees like state troopers, the folks who maintain roads, and run the various state agencies. Another 10% or so comes from private pension funds.

When private equity firms steal from their investors, they get less in the way of returns than they deserve. Public pension funds in particular are often underfunded because state officials chose to underfund them (the most underfunded pension system in the US, New Jersey’s is underfunded due to Christine Todd Whitman’s decision: http://www.nytimes.com/1995/02/22/opinion/in-america-whitman-steals-the-future.html). But even healthy pension systems have suffered some stress as a result of the financial crisis (remember, they had to keep paying retirees their committed amount, even asset values had fallen, which took a toll on overall funding levels).

Reduced returns for public pension funds means some combination of these events happen: taxes get increased and government service levels get cut to make up the shortfall, or (down the road) retirees get screwed.

What is the actual % yield for these public pension funds which invest with these PE firms, even after the fee games are played on them? Are the gains on balance significantly larger than a Vanguard or other broad market investment would garner?

Hahaha, you want data? Why do you think I sued CalPERS?

Guess what: there is no industry-wide data set. None. This is a strategy that has been around for over 30 years, yet PE-friendly McKinsey thinks only 2 decent studies of PE returns have ever been done. The industry has supplied cherry-picked data sets to researchers (who pretty much all sit at business schools that have PE firms as their biggest donors). They tend to use the S&P 500 as the comparison benchmark, when the average size of a PE investment is vastly smaller than the market cap of the average S&P 500 constituent stock. To the extent there is data, it’s quarterly, which is more approximate than it needs to be. The industry has also promoted the use of IRR as a return measure, which is a poor measure, particularly when you have volatile cash flows (which PE does). If I had used IRR to calculate returns in a finance exam in Bschool, I would have gotten a failing grade.

I will be writing up a chapter from the excellent new book Private Equity at Work on PE returns, and they argue that PE outperformance is modest and not enough to compensate for illiquidity risk, given investors’ own assessments of how much extra return they should receive to compensate for the illiquidity. One reader sent an analysis that showed that 90% of the state pensions would be better off by switching to a portfolio of four Vanguard funds (total stock market, total bond, total international, and REIT Index). I am reviewing that and if I think the work is robust enough, will be publishing it soon.

So Muppets are still the base of the food chain, on the value menu, and predators in cahoots(?). I suppose this is what your CalPERS suit is targeting. I certainly hope it’s successful.

Aren’t the PE firms also preying on the portfolio companies? How can a potential portfolio company protect itself?

How can a pension fund protect itself?

Do PE firms assume no one will challenge how the language of an agreement will be interpreted after an agreement has been signed? Have firms (either portfolio companies or investor funds) ever refused to pay these questionable PE firm fees?

Oh, yes, at all size ranges the companies get squeezed, but in the smaller deals, the PE funds typically do make operational improvements (they focus on companies that would benefit from having the business run on a more professional basis). The large and mega-deals, which is where the bulk of the industry dollar go, achieve their returns through financial engineering and cost reduction, which generally means headcount reduction.

And the portfolio companies can do nothing about it, their PE overlords are in control.

The PE firms control the cash flows, so the investors are in no position to intervene. As the SEC’s Drew Bowden said in a recent speech:

[A] private equity adviser is faced with temptations and conflicts with which most other advisers do not contend. For example, the private equity adviser can instruct a portfolio company it controls to hire the adviser, or an affiliate, or a preferred third party, to provide certain services and to set the terms of the engagement, including the price to be paid for the services … or to instruct the company to pay certain of the adviser’s bills or to reimburse the adviser for certain expenses incurred in managing its investment in the company … or to instruct the company to add to its payroll all of the adviser’s employees who manage the investment.

Wow. With PE controlling the cash, and portfolio companies needing it, and investor funds (such as pension funds) needing a place to put their cash–PE firms can do whatever they like, it seems.

That upcoming article on a portfolio of four Vanguard funds (comment above) providing better returns for investor funds sounds very interesting.

In Morgenson’s Silver Lake example above, I can’t tell who the “advisers” (the “contractors”?) supposedly work for, who pays them originally, and where the funds go after that. Can someone please explain?

The contractors are under the direction of the private equity general partner. But their fees are paid by the portfolio companies.

The sneaky bit is the investors assumed these people’s pay was coming out of the management fee (the prototypical 2% paid annually by the investors to the private equity general partner), and not a separate charge against the portfolio company (which reduces income to the investors).

Thanks. I love your clarity.

“…including getting paid for services never rendered.”

I am constantly amazed at the commonality of the techniques used to defraud people. They cross over Industry lines and have a Universality about them. It is as if there is a Central Institute For Fraud (tax exempt, of course) governing all aspects of our lives.

In this case, I posted the other day about the Placebo Effect. There the Doctor bills and gets paid for services rendered not by the Doctor but by the patient! Move over, Wall Street. What is also remarkable about this is that some Doctors know about the Placebo Effect but just keep on billing. Mum’s the word; don’t kill the Fraud Goose.

The diagram seems to indicate where the commonality of these techniques originates from. The private equity firms are given full control of the fee structure, and investors appear willing to give over control. It’s the Management Theory of the (Private Equity) Firm in action.

Honestly, I would be inclined to blame the “victim” here, the investors, but the reality is that they themselves are simply another layer of fee taking management over the true victims with their money inside these funds.

So nice to learn that Punch Sulzberger’s dedication to the Arms and Armaments Department was in fulfillment of a boyhood dream and not restricted to his shaping of the news.

Over and above the underhanded way these leverage buyout looters operate, which most certainly deserves exposure, I would like to see more on the social utility of what these entities do to the real economy. For example, whereas George Romney ran one company, American Motors, Mitt Romney bought and flipped over 100 after extracting “management fees” and “dividends”. The Los Angeles Times reported that of the ten largest companies bought and flipped by Bain Capital when Mitt ran it, four went bankrupt. How does that fit into the larger picture of economic decline in the last 35 years?

…the goal of a LBO is to gain control of a company, strip it of assets, and leave it burdened with debt. After the Romney’s, et al, have taken their profit. ” Creating a more efficient company” is simply PR.

I guess this shows that the big bosses like to feed on the little bosses so to speak. Eventually, as these finding become better known among investors they’ll learn to put their money elsewhere like maybe something that benefits human beings even just a little.

Sadly, in our system it is investors that run the world and determine what sort of world we live in and will live in–ultimately, TINA is the fact we all have to face. As many of us have written here for some time the system is too corrupt for reform–you may change one rule it may ease things a bit then the regulators are bought off, law enforcement is bought off or neutralized politically, i.e., there are people within Justice that wanted to prosecute criminals in the aristocrat class but the highly corrupt Obama administration won’t let them or least haven’t as we speak.

I say take away the elaborate regulation of Wall Street and let them regulate or steal from each other as they please. Meanwhile the minority of investors who have some interest in something other than greed and moral depravity (they go together) can either establish new markets or support those that exist like crowd funding etc. and put your efforts in that direction. This is why my initial reaction to the article is “who cares?”–I mean, I’ve known rich people and I really don’t care if they get hidden fees or whether their brokers or general partners take a portion of their money–it’s all crime as far as I’m concerned if it occurs on Wall Street–I say that reluctantly because I know there are still a few decent people in that world and to those I say get out and be a part of the real world that needs you badly. I would say the same to people who work in Washington–get out, go home, find new structures working in the old ones even if you think you can do good harms all of us and yourselves.

It’s not just rich people stealing from rich people. The LPs are often pension funds, which means that the money at play is that of pensioners, not the rich.

However, your point about creating alternative investment mechanisms for people and institutions concerned with more than making as much as possible in the Wall Street casino, is right on. I’d love to be able to see a way for local businesses to issue bonds to raise capital and for locals to invest in those bonds.

As for the big bosses feeding on the little bosses, “sh*t rolls downhill,” as they say, which means only those at the very top of the hill don’t end up with sh*t all over them. Yet another reason to prefer horizontalism to hierarchy.

Re: alternative investment vehicles, Cutting Edge Capital is a company that specializes in a range of alternatives. They have an innovative approach to fee structure designed to make them more accessible to the companies raising funds. I heard about them when looking into Marjorie Kelly (“Owning Our Future”, etc.) ‘s background.

The limited partners are in a battle with general partners over the spoils of financial rape of society at large.

In Ontario we have the same thing going on with the Ontario teachers pension fund. The fund partners with PE firms and gets raped by those PE firms, and when their money bucket isn’t full enough, demands and gets a fill up from the taxpayer. They have diversified by investing in, among other things, Spanish shopping malls. That should turn out well.

Those paying for it can eat dirt. Popcorn is too expensive.

Thank you for this article, Yves.

“In some instances, investors’ pockets are being picked,” Andrew J. Bowden, director of the S.E.C.’s office of compliance inspections and examinations, said in a recent interview. “These investors may be sophisticated and they may be capable of protecting themselves, but much of what we’re uncovering is undetectable by even the most sophisticated investor.”

Economic systems are designed to do EXACTLY this. The difference between the elite [including their lackeys in the professional class] is that they understand this and attempt to maximally exploit its potential, while most everybody else can’t possible figure out where things have gone so very wrong.

The more complex systems become, the further they move from the truth [increasing complexity is proportional to decreasing transparency].

The key is that technology does not necessarily need to foster complexity. All truly great inventions [innovations] have been incredible simply [in design and function], for example, the flush toilet.

I am so glad this is all coming out. I am perhaps overly optimistic (which I have been accused of, but which has served me well during some pretty rough times) but I am enjoying watching all these extractive industries being jilted by other extractive industries/rich people. For example, gig commercial property borrowers are going to insurance companies instead of commercial banks for loans. Two reasons: Much lower fees at insurance companies, plus a long term view of the collateral. (The banks use short term money, want to flip/sell the loan, plus extract enormous fees/points.) Plus the insurance companies have experience with real estate, and you will not get into a sitch like I did with Chase where the bank will call a current note which has expired, (and extract cash at a fire sale, while losing a sh*tload off the note, but hey, it goes into the profit column this quarter, and Slimin’ gets his bonus. Multiply thousands of times. ) rather than refi it. Especially if it has full collateral values. The FT reports commercial property loans are down 50 percent at commercial banks since the crisis, during a commercial property bubble. That’s why the banks are doing so many covenant-light loans for mid-size businesses. (That will turn out well!) Who cares about fees/costs when you’re going to be Chapter 11 anyhow, and the loan lets you borrow to make payments.

Trading is way down in banks because only a fool would trade through a front running bank (so much better to trade through a front-running HFT.) The banks, such as Chase, are dumping commodities because profits are way down. You may rest assured if they were still minting money, they would fight to keep commodities, just as Goldman is. (May GS get burned like hell by the market for that.)

As more info comes out about PE fees, the rich will move their money. Sadly, the pension funds (especially the government pension funds managers who are apparently all on the take (s proven here in California court against CalPers with “placement specialists”) will stay in until everything is a smoking wasteland and their pensioners are all wiped out, as @cnchal noted above.

It is slow, but since the SEC, AG “Place Holder”, the new bankster-friendly CFTC, etc. will do nothing to stop the rape and pillage, one can only hope the market will. Of course, we taxpayers will be left holding the bag if it happens too fast. But, we will be anyhow as we continue to support all the people displaced by the PE company liquidation/inferno. Maybe Slimin’ et al will just have to do with less.

Numerous recent Obamacare stories have been announced on these worst possible days. Here is an example:

http://www.nytimes.com/2013/01/01/health/employers-must-offer-family-health-care-affordable-or-not-administration-says.html?_r=0

This was the story that introduced the “family gap” or “Family glitch” which I think was obviously intentional

Here is another story that was deliberately downplayed and then squelched by the media- This shows how the incremental bait and switch game has been operating.

http://www.cjr.org/the_second_opinion/the_ap_downplays_its_own_obamacare_scoop.php

You need to remember who owns the major media outlets in this country – and worldwide. Namely, Rupert Murdoch. You also need to remember his political leanings. Then it will all become clear. BTW this is actually one of the *least* obvious abuses of the press that I have seen from his media empire.