By Ignacio Portes, a freelance journalist who lives in Buenos Aires. He has been published in English at PandoDaily and NsfwCorp

See part I for background on the legal battle

With Argentina’s payment to the holders of its restructured debt on June 30th in limbo at the Bank of New York Mellon, blocked by Federal Judge Thomas Griesa, and the 30 day grace period to official default ticking away, financial pundits have taken a keen interest in the biggest debt struggle in memory.

Some have been very critical of both the judge’s interpretation of the pari passu clause that created this mess and, more importantly, of his damaging precedent. Martin Wolf at the Financial Times compares Argentina’s position to that of a debtor prisoner extorted by the US judiciary. Floyd Norris, in the New York Times, highlights how the ruling could allow a single creditor to block beneficial and consensual restructuring plans.

But no one seems able to resist adding digs at Argentina, even when generally supporting its position in the litigation. Wolf, the most understated of the lot, still says:

It was difficult to feel much sympathy for the country, which suffered from chronic mismanagement before its default in December 2001 and was to suffer yet more thereafter.

And there’s no doubt Argentina has suffered from mismanagement, but the nature of nation-states means that often that management comes from a very different section of society to the ones that end up suffering its consequences. Dictatorships are the most obvious examples but far from the only ones: the idea of any country being so economically democratic that harsh outcomes for vast parts of its populations are deserved should be seen as preposterous. But it’s such a tenet of neoliberalism and IMF “reforms” that the notion is treated more seriously than it should be.

Floyd Norris repeats almost verbatim that it’s hard to feel sympathy for the country and goes further:

The case concerned an appeal by Argentina, a country that the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit called, with ample reason, “a uniquely recalcitrant debtor.” This is a country that has made default a national habit over the last two centuries, making you wonder why anyone ever lends to it…

It is hard to muster much sympathy for Argentina, which chose to cram down a brutal restructuring plan years after defaulting, when it reasonably could have been more generous.

Norris opts for easy clichés about reckless abuse of honest lenders by a country of irresponsible conmen rather than considering that entire populations aren’t naturally inclined to be recalcitrant debtors, but that they can become skeptical towards lenders for understandable reasons, or that at some instances they simply can’t find a way of paying even if they went hungry trying.

If you actually look at the last two centuries that Norris mentions, Argentina has been far from a particularly irresponsible debtor. Whatever you think about them, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff made possibly the most comprehensive study on the matter up to date in This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly, and here’s what they concluded:

Our dataset reveals that the phenomenon of serial default is a universal rite of passage through history for nearly all countries as they pass through the emerging market state of development. This includes not only Latin America, but Asia, the Middle East and Europe. We also find that high inflation, currency crashes, and debasements often go hand in hand with default. Last, but not least, we find that historically, significant waves of increased capital mobility are often followed by a string of domestic banking crises.

Pick almost any developing country and you’ll find that debt crises, restructurings and defaults are far from rare. But not only is the problem structural, the history of Argentina that Norris pretends to know actually shows it in quite a different light.

If you exclude the delays in payment caused by the 1982 debt crisis (more on that soon), you have to go to 1890 to find a previous case of clear-cut, unilateral default of foreign debt in Argentina, and it didn’t last long: an armed uprising forced oligarchic president Miguel Ángel Juárez Celman to resign one month after it decided to stop paying back its suddenly skyrocketing debts. The remaining government promptly raised taxes, froze corrupt public works, sold assets and gold reserves and took new debt in order to restore payments and stabilize the economy, with relative success.

Since then, Juárez Celman has been universally remembered as an authoritarian crook (a rare event in a country where someone’s villain is always someone else’s hero), while the revolutionaries are generally portrayed in a positive light in Argentina’s public education and media. Doesn’t look like what a default-happy country would do.

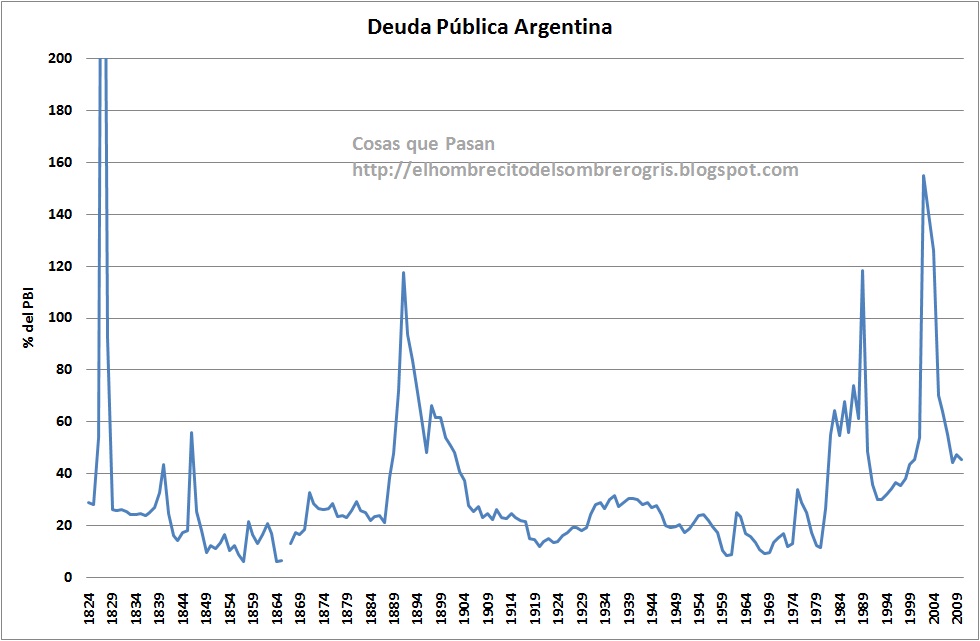

The new century came with a booming economy for Argentina. Its public debt-to-GDP ratio fell sharply, from about 120% at the time of the 1890 crisis to below 40% 15 years later. Throughout the first three quarters of the 20th century, it would never grow higher than that, not even after the 1929 Wall Street crash, when Argentina was one of the very few countries in the region that avoided default. At times, debt even dropped below 10% of GDP. Again, far from the performance of a stubborn gambling addict that doesn’t know whose door there’s left to knock for a bit of cash; quite the opposite, in fact.

So what changed? Reckless gamblers took control of the country and broke its bank.

After oil-exporting Arab countries shocked the world’s markets in 1973 by concerting a rationing policy that sent oil prices through the roof, massive amounts of petrodollars started to flood into their coffers, and capitalist logic indicated that all this surplus had to be invested somewhere. Latin American was a big target for petrodollar investments, especially the private sector. In 1976, the bloodiest coup in Argentina’s modern history installed a military government that, following a continental trend, decided that controls over capital flows should be loosened.

The whole policy of indebtedness changed in Latin America. As Robert Devlin and Ricardo French-Davis describe, standard procedure in previous decades was that states borrowed money from multilateral institutions for concrete development projects, with clear goals in mind. Growth was slow, but typical boom and bust bubble-like crises that end with massive unemployment were avoided. Then, those international organizations were optimistic about these sudden capital inflows, because markets were supposed to be more efficient allocating those funds than centralized institutions. They ignored that private debt can burden a country’s economy, especially if it is as short-term as this was.

As long as private credit kept being cheap, banks and other companies kept re-financing those short-term, low interest bonds. It was great business for them in Argentina, because the dictatorship allowed them to commit all kinds of fraud against the state’s coffers to ensure that the loans would always earn those companies money, free of any entrepreneurial risk.

The fraudulent mechanisms were almost unlimited, as Argentineans from all over the ideological spectrum have documented over the years, from nationalist Alejandro Olmos to US-friendly liberal Carlos Escudé.

Interest rates on bank deposits were deregulated, allowing them to rise, but the military junta declared that all deposits would be covered by the state in case of bankruptcy. That eliminated all incentives for bank counterparties and clients to check the creditworthiness of particular institutions: any bank was good for an investor, and banks could re-invest that money anywhere too, as the state would cover the bill if things went badly.

At the same time, the military junta established a crawling peg system of scheduled mini-devaluations. That meant investors could anticipate how many pesos they could get for a dollar at any point during the next year. Combined with the short-term, high interest rates deposits that the new banking regulations allowed, this meant the bigger and safer gains for the financial sector were done by moving all its resources away from productive industries and into speculative but risk-free bets against the local currency, the peso.

Shrewd traders got dollars from abroad, sold them just after one of the scheduled mini-devaluations, and put the resulting pesos into fixed-term deposits, at a high interest, for short periods that lasted just until the day before a new devaluation was scheduled. At that point, they took the pesos plus interest out of the bank, and bought slightly more dollars than they initially had, at the same price at which they had originally sold them, but knowing they would be worth more the next day, when the cycle would be restarted.

Money was magically multiplied, with the speculators having produced nothing, nor taken any risks. The only loser was Argentina’s Central Bank, whose dollar reserves kept shrinking.

That wasn’t the only form of financial gamesmanship at the expense of the public. Other loans were used to invest in infrastructure projects that the state auctioned, such as the highways that today make Buenos Aires’ traffic hellish. But the state guaranteed by contract that it would chip in with several hundred million dollars to ensure that the projects would always be profitable no matter what, if needed. And it was always “needed”.

So a private contractor took loans for, say, $300 million to build a highway, even if it knew it would only get $100 million on road toll income in the period the contract lasted, and even if the real cost of building it was $80 million, because the state would pay the rest. Everyone suspected that the government officials in charge of these contracts got kickbacks, but since they couldn’t be voted out of office, those rumors didn’t bother them too much.

The military in control of the state took some of those petrodollar loans too: about 10 billons were used to buy weapons to finance state repression and insane war projects with Chile and the UK.

It wasn’t much compared to the private debt that all the big financial players had gotten into, though. But the state ended up paying for that too, by nationalizing it in 1982. It didn’t matter that much of the private debt wasn’t even real debt, but money that had been “loaned” from the headquarters of multinational corporations to their local Argentine branches, not to produce anything but to speculate on any of the wide variety of schemes explained above, and send the easy profits back as “repayments”. The state also didn’t get into too much trouble finding out how much debt was real and which one had already been paid back. If they are going to pay it all, I might as well claim I owe every cent I borrowed in history, especially if I’m going to be the one in charge of the audit, reasoned the bailed-out banks and companies.

By 1983, when the 8 years of military rule were over, public debt was 465% bigger than the year of the coup, and there wasn’t much to show for it in terms of improvements for ordinary Argentineans. Financial institutions and corrupt military officers had stolen most of it, and flown it out of the country, while Argentina was already lagging behind its scheduled payments since the Latin American debt bubble exploded in 1982.

By the time Raúl Alfonsín was elected into office, debt was unmanageable, with short-term due dates every other day, in the midst of a barely governable country, where the criminals that had been tormenting it for the last decade were in control of the military, police and trade-unions, in association with the parasitic businessmen who made their fortune during the dictatorship and now had amazing leverage over the economy.

At first, the new government tried to rally all of Latin America into declaring the debt acquired during the dictatorships illegitimate, but it was too weak on many fronts already to undertake such a battle, and soon gave up. This was taken as a sign that the country “accepted” the debts acquired during the dictatorship as valid, making any future prospects of declaring it “odious” null. Quite a debatable interpretation of what happened, but try telling that to an international court of law.

This debt-to-GDP ratio graph illustrates the story well: very low since the recovery from the 1890 default until the private debt boom of the 1970s, which is invisible at first, but then suddenly present when the dictatorship bails out big debtors in 1982 and the economy then lags for seven years more, ending in the 1989 hyperinflation that wiped much of the locally issued debt, at great social cost.

Recent history might be more familiar. Latin America found its foreign debt burdens slightly eased in the early 90s due to the Brady Bonds restructuring, combined with massive sales of state assets. Indeed, many state companies, run down after years of undemocratic and corrupt management, were bought on the cheap with bonds that the state had no way of repaying otherwise.

Creditors started lending money to the region again, but in Argentina the banks inflated their way into another bubble. It was masked by the fact that GDP grew for some years too, while the overvalued peso, pegged to the dollar, made it seem as if the debt-to-GDP ratio was even better, with GDP overestimated. But by the end of the decade Argentina had more than doubled its debt, and a five year recession destroyed much of that GDP growth. When the IMF, which had facilitated the whole process, suddenly started to play hardball, the country was doomed to default.

None of the latest Argentine governments have covered themselves in glory, far from it. But the arguments that blame countries in trouble with debt for all its problems serve to perpetuate the mythology of capitalism. Since capitalism allegedly rewards merit and hard work, its results must be fair. All that is needed are small adjustments here and there.

Mainstream liberalism often ends up looking like a priest telling the sinners they should be ashamed of themselves for not being pure enough, explaining they’ve doomed themselves. Invoking cultural stereotypes always helps: Greeks with their laziness, Argentinians by being capricious teenagers that want to break the rules and then blame conspiracy theories. The convenient narratives of success and failure must obscure critical facts in order to hide a more nuanced understanding of who is to blame for national train wrecks.

Here in the EU we generally know it is the EU that is largely responsible for our economic headaches. That is no secret. Countries like Spain take to the streets regularly to demonstrate their disgust with the system. What we have is a bunch of misguided economists and EU leaders who frame the argument like this: you are in the funk you are in because of fiscal irresponsibility. Naughty! The way to get out of your mess is commit to ‘reforms.’ Magical ‘reforms’ will send you to the promised land and provide ‘stability’ and ‘confidence’ for all. I have no data to back this but my guess is folks have bought into this jive talk because the elites make the financial problems sound like balancing a checkbook.

Like Argentina, we get our share of international pummeling from economists and elites who have no sympathy for our economic policies. Unfortunately, from what I can see, no one here in a position of authority is paying them any attention.

I am afraid that this is a bit of an over-generalization – in Germany, conventional wisdom is that the Eurozone “periphery” (note the nomenclature) is in trouble because of their social/economic/moral defects since Germany is in the Eurozone as well and supposedly not in trouble.

And in France, the main narrative takes the form that France is like Spain and Italy but should better be like Germany – hence neoliberal forms.

Frontier debt does have a habit of scalping the greedy and green horns… somethings never change… snicker….

Hmmmm… I wonder who the vulture funds are….

“often that [mis]management comes from a very different section of society to the ones that end up suffering its consequences. I would venture to say always.

and who sees that these harsh outcomes for vast parts of its populations are deserved? Often members of the same club so to speak as the ones lending in the first place? What were they saying when all that lending that Norris wonders about now was going on? The kleptocrats feeding off those loans? Fine with it when it was lining their pockets.

And then the powers in the countries pushing these policies of suffering, together with their willing media, rouse their populations to blame the ones least politically powerful via the greeks-are-lazy style memes. Channel blame to lazy people who would rather collect welfare than work, big government, …works great to implement austerity, to privatize, gut government. And avoid putting criminals in jail.

A site called FactCheckArgentina.org popped up four days ago. The site is sponsored by American Task Force Argentina, which lists a couple of dozen members. But presumably Elliott Associates is the main one.

Recognizing that the site has an ax to grind on behalf of creditors, here’s what it says:

Economy Minister Axel Kicillof recently posted a letter to the Financial Times responding to an op-ed published there by one of Argentina’s creditors.

After railing against Argentina’s creditors and trying to rewrite the history Argentina’s bond exchange, Kicillof proclaims that Argentina’s “willingness to move forward in a dialogue” is evidenced by his meeting with Special Master Daniel Pollack on Monday afternoon.

But Kicillof’s own account of that meeting indicates that it was not a dialogue, but a one-sided harangue that culminated with yet another request for an open-ended, unconditional stay of the district court’s ruling.

Kicillof complains that, because “the vulture funds opposed” Argentina’s unconditional stay request, that this proves “they do not want to negotiate.”

The balance of Kicillof’s response to the op-ed is filled with more insults and accusations. He accuses Argentina’s creditors of “extortion,” then falls back on the same over-the-top rhetoric about the district court’s ruling that the Second Circuit Court of Appeals branded “hyperbolic.”

http://factcheckargentina.org/

———–

Setting aside the bias of the site, the fact remains that Kicillof has made three trips to the U.S. in the past few weeks. On none of those occasions has he sought a meeting with the creditors, the principal action which Judge Griesa is encouraging.

Owing to the RUFO clause in the existing settled debt, possibly Argentina’s legal strategy is to shun negotiations and default, rather than to reopen the 2005 and 2010 settlements. That result looks about 95% probable at this point.

But Kicillof’s baffling claim that Argentina is ready to negotiate, while avoiding any actual negotiation meetings, comes across as flaky. Perhaps this is just an inscrutable aspect of the latin character which doesn’t translate into the square-headed anglosphere.

And a fresh fusilade from Argentina, via La Nación in Buenos Aires:

Cabinet chief Jorge Capitanich said the economic minister, Axel Kicillof, will not attend tomorrow’s meeting with special master Daniel Pollack, the negotiator appointed by Judge Griesa. Instead, members of the ministry’s “legal and financial team” and “other areas of government” will go to New York.

Capitanich referred to the statement released today by American Task Force Argentina (AFTA), the main lobby group against the country claiming payment of the debt, presenting “myths” and “facts” about the war against the holdouts.

“Argentina’s position remains the same: we will in no way accept strategies promoted by tiny minorities who are unwilling to negotiate,” he said. Capitanich insisted that the position of Argentina is “not to be extorted.”

In his regular press conference at Casa Rosada, the coordinating minister spoke of the holdouts’ “mafia campaign” in “parliaments of other countries” and said U.S. lawmakers receive “financing from vulture funds”.

http://tinyurl.com/ll6zx88

————

In diplomatic terms, Argentina is downgrading the rank of its delegation at tomorrow’s meeting. Meanwhile, it claims that its opponents won’t negotiate, while declining to call them to set up a meeting.

While Argentina’s claim that members of Congress are receiving contributions from hedge funds is probably true, it is hardly going to generate any official goodwill on the U.S. side.

This is supposed to be an effective strategy how? Note it in your calendar: 30 July, Argentina defaults.

“Setting aside the bias of the site”….

That’s laughable, given the “fact” that it’s 63.44% of your comment with the added sophistic benny of being the introductory 63.44%.

If a debt becomes un-payable, can a judge’s gavel magically change this basic “fact”?

Is the making of Singer’s predatory business model, a viable one, a legitimate use of “our” legal system? Is that a “justifiable” use of ‘our’ venerated and wise minds of ‘justice’?

***************

“According to an old legend, vizier Sissa Ben Dahir presented an Indian King Sharim with a beautiful, hand-made chessboard. The king asked what he would like in return for his gift and the courtier surprised the king by asking for one grain of rice on the first square, two grains on the second, four grains on the third etc. The king readily agreed and asked for the rice to be brought. All went well at first, but the requirement for 2 ^ n − 1 grains on the nth square demanded over a million grains on the 21st square, more than a million million (aka trillion) on the 41st and there simply was not enough rice in the whole world for the final squares. “- Porritt, Jonathan (2005). Capitalism: as if the world matters. London: Earthscan. p. 49.

Assuming no “regulatory capture” and a “Justice System” that is indeed “just”:

If King Sharim had signed a contract, would it be binding? If so, could it be enforceable? If enforceability were pursued, would King Sharim eventually become a peon and vizier Sissa Ben Dahir his Lord? Would the eventual inequality be considered just? Can presenting the impossible as possible be considered fraud?

Here’s a video inveighing against the vulture funds. Spanish judge Baltasar Garzón makes a cameo appearance:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=XZLKTOXGxyA

Thanks…that was much more compelling than Singer “singin the blues”…

Singers’ business model is fundamentally and morally repugnant…”equal footing” within a functioning “justice system”would have put Singer on equal footing with the rest of the creditors, i.e., restructured.

THE FRAUDULENT CONVEYANCE PRINCIPLE

“A broad guideline for writing down debts was developed more than two centuries ago in the American colonies. British speculators and sharpies eyed the rich farmlands of upstate New York and refined the practice of making loans to farmers against their crops. Their strategy was to call in loans at an inconvenient time (e.g., just before harvest), or simply to loan the farmer more than could realistically be repaid in the epoch’s low-surplus economy. They then would foreclose.

To cope with this problem, the colony of New York passed the Fraudulent Conveyance law. This was retained when New York joined the United States, and remains on the books today. Its principle is that if a lender makes a loan that the borrower cannot reasonably be expected to pay off in the normal course of business-that is, without forfeiture of property-the loan should be declared null and void, and the debt cancelled. The legal assumption is that such a loan was a ploy to gain control of property pledged as collateral, over and above simply earning interest.

The aim is to keep debts within the ability to pay, by placing an obligation on bankers and other creditors to make viable loans rather than covert property grabs………………………..

The Fraudulent Conveyance principle may be applied to the public sector with regard to pressure brought on debt-strapped governments to sell off public enterprises to pay creditors…………….Banks and bondholders have lent governments credit as if this were risk-free……………… Banks and bondholders are thus in the position of the British financial sharpies making ostensibly reckless loans in the belief that the local sheriff and other colonial officials would back up their property grab……”

–Excerpt from “The Bubble and beyond” by Michael Hudson

http://youtu.be/KYW5Lxm_Kjs?t=18m59s

What is interesting that a significant portion of Argentina’s debt was sold for pennies on the dollar to financial outfits that then claim the full amount of the debt. Like in America where companies will sell outstanding debt to collections agencies for pennies on the dollar; where the collections agencies then attempt to collect on the full debt. Or settle for much more than they bought the debt for.

That site is hilarious. Even better is the ATFA site, which seems to be redirecting to the fact check site at the home page level but which you can still see via internal links, like this one:

http://www.atfa.org/about-us/

Check out the posters in the right sidebar.

Nice trick registering a non-profit organization to handle your propaganda. I bet they get all kinds of favorable tax treatment from it.

If I was Kicillof I wouldn’t want to negotiate with them either, although I agree trying to simultaneously present them as being unwilling to negotiate is a bit of a stretch.

If Argentina can drag the clock out to the end of the year, they are fine.

I’d love for them to say, ok, anyone who shows up in person can get the debt then put out arrest warrants on singer and co.

I’m not sure the article fully answers the question in the headline. It would be interesting to know just who the original creditors were for these “vulture fund” holdings, particularly the ones in the court dispute.

I think the author’s primary intent was to demonstrate Argentina’s foreign debts were due not to government borrowing but to a lack of capital controls and failure to prioritize productive investment over financial speculation. Like you, I had assumed from the headline this would deal directly with the involvement of Singer and his ilk but there is still some useful info in the story, particularly for those who don’t pay a whole lot of attention to capital mobility and its destabilizing effects.

Yes. The last step where this ridiculously conceived debt was left not spelled out in the article because what happened is what Vulture Funds do by definition: Argentina defaulted in 2001 when, after a couple of decades trying, it just stopped being able to service it, and Singer and other Vulture Funds bought the defaulted bonds from the weakest people unfortunate enough to hold them at the time, at 5 to 10 cents of the dollar, and as they have all the time of the world to wait for max profit, they sued Argentina and are on the verge of beating them for full payment after more than 10 years of battling. A nice 1000% return for their investment, no matter the costs. It’s not the first country where they’ve done it, and it probably won’t be the last.

The last step where this ridiculously conceived debt ended in the hands of the vultures was not spelled out in the article because what happened is what Vulture Funds do by definition: Argentina defaulted in 2001 when, after a couple of decades trying, it just stopped being able to service it, and Singer and other Vulture Funds bought the defaulted bonds from the weakest people unfortunate enough to hold them at the time, at 5 to 10 cents of the dollar. As they have all the time in the world to wait for max profit, they sued Argentina and are on the verge of beating them for full payment after a decade of battling. A nice 1000% return for their investment, no matter the costs. It’s not the first country where they’ve done it, and it probably won’t be the last.

The money has long since fled and been scrubbed clean. It went around and came around to the final round of vultures who tried their scam one last time and failed to see any returns. So they took it to a kangaroo court and won. What a ransacking. Of course it is set off in the first place by “investing” which is so looney it will never pay off, and then it all spirals out of control. Ah… isn’t capital a wonderful thing? Just watching Max’s interview with Robert Steele; the post here last week on his book “The Open Source of Everything Manifesto.” And he basically says, It’s the productivity, stupid. And points out that real productivity has nothing to do with financialism, aka money. Max asked the question, Well if all risks were taken into account (so looting could not happen nor could the socialization of odious debt occur) what would the DOW be today, 3000? To which Steel replied it was a good question and he didn’t know the answer. I submit the DOW would be at 30,000 to reflect the true costs of democracy.

I support Argentina in this epic battle, but what happens once they are in default? It appears that to stay in the game, Argentina must either pay up, enriching the vultures and perhaps bankrupting itself, or default in earnest. My guess is that all Argentine assets globally would be at risk of siezure, which seems completely nuts, would likely lead to Argentina nationalizing broad swaths of private developments in Argentina – and alignment with Cuba and Venezuela. Wait a minute, that just might be the smart thing to do. For every dollar U.S. courts allow to be confiscated following default, Argentina should confiscate an equal amount of foreign owned property in Argentina. Crazy? Maybe. But paying the vultures would be crazier. While I empathize with the people of Argentina, I am quite interested to see what happens next.

Even if we accepted Floyd Norris’ claim that Argentina is so uniquely horrible a debtor that it doesn’t make sense to lend to them, why would it follow that the debtor needs to be punished? And the debtor alone? Wouldn’t it be more sensible to think that anyone foolish enough to lend to a “uniquely recalcitrant debtor” should be punished for their foolishness with their money? Why have we accepted the premise that people who put money into risky investments shouldn’t shoulder the actual risk when the investment doesn’t pay off in the end?

Financial/Economic warfare, that employs usury and speculation, exists as the basis of Imperialism, we call Globalization today. A rigged to fail, unpayable debt is created as the pretext to invade, at least destroy the principle of sovereignty and take land and resources the International Financier Supremos do not have to pay for. The NY court decision was a horrendous, brazen assault on humanity. The SCOTUS refusal to review Argentina’s appeal legitimizes and furthers the economic warfare presently conducted across America today. The SCOTUS and the Congress are unable to free itself from Wall St. extortion, it is the national security crisis.

We should be reviewing Pres. Roosevelt’s statecraft that secretly, subtly threatened war on Germany, England and France over the 1902 Venezuela debt crisis. Pres. Roosevelt understood an attack against one was an attack against us all and that land and resources was the true objective. The loan documents and terms, merely the device, that operates pillaging and plunder. The entire world and Americans must look to terminate the bankrupt, bailed out Imperial system, that is destroying the cities of Detroit, Chicago, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Stockton, Oakland, St.Louis; most states and cities across the nation are under the Private Sector’s debt trap siege.

Looking to Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Syria, Iran, Ukraine, is the threat of thermonuclear WWIII against Russia and China, as a result of the insane hope that the disintegration of the world financial system can be disguised, and fortune exists in war, facilitated again, by the demand for more land and resources. Humanity’s existential crisis exists in this story once expanded to its true perspective and dimension in realty today.

My thoughts align with Clarc King’s comment.

A recent peek behind the Global Banking Wizard’s curtain; into the dark pools of money skimmed off high speed trades seems to have many in Congress naked for all to see who enabled the plundering of a multitude. ‘Follow the money’.

As I read the article, the cities around the Great Lakes came to mind, and the organized move offshore that began in the 1980’s. They ‘downsized’, while spewing enough toxins from their smoke stacks to sac public health and drive up cost to all businesses – which made it a win-win to go offshore and reap the extra benefits of Bill Clinton’s tax breaks for offshore profits, and George Bush’s tax breaks to companies that hadn’t already made the move offshore. A Good Old Boys ‘one-two punch’ with Bush & Company delivering the second blow to the middle class by cleaning out wealth for much of the middle class and strapping the working poor with the cost of what is not carried on profit and loss statements by big industries, but works in the environment to sicken populations that will push up job numbers as the ranks of the sick swell the for profit health system.

‘Watch the birdie on the border’… as the money Bush spent to build a wall after cutting funds for actual patrols leaks, and now floods children of Mexico into the U.S. to shame President Obama. Really? Also, ‘keep and eye on the birdie in Iraq and Afghanistan where trillions of dollars evaporated in the hot sands and now those who were ‘trained to defend their nation’ seem to lost hold of a number of cities? Really? “Who’s Zoom’n Who?”.

With the decades of images of a growing global population, and fixed business models that ‘Good Old Boys’ now have the ‘magic powers’ to form demand to suit what they choose to supply, maybe we should be grateful for the slippery slope and a hastening of the knell.

The reality of unfettered science is that it is rife with ‘unintended consequences’ and those ‘consequences’ might portent a repeat of history where the market bell is a knell on the 1% as the entire world says “Enough is Enough!”… and the bubbles begin to pop! pop! pop! … while the offshore island banking structure goes under high seas.

“Keep your eye on the birdie” as it chirps loudest away from it’s nest (media monopolies).” With so much vested in operations in China, and Russia too – by U.S. British, and E.U. firms – are they really going to all of a sudden close up shop and pay taxes on trillions of dollars sitting offshore when they control all of our infrastructure and it’s so far beyond the average citizen to realize or even grasp how far into the bowels of a totalitarian beast we all are? The world is being fleeced by a few who saw an opportunity to turn the advances of science and technology into their favor… (and make sport of it on select citizens they covertly tortured – ‘just to be sure it would work on an enemy’) that is, until the Toto’s (whistleblower’s) pulled back the curtain for a peek at who and how the financial sham is being fabricated.

“RICO ACT” comes to mind, and a warning: Don’t believe that technology that allows a user to use their mind to drive a vehicle or take a photo with the new Google Glass only works one way – from a persons thoughts to an object – it’s a two way street and remote access is part of the new age infrastructure.

Years ago there was a commercial that said: “Do you know where your children are?”; then it progressed to: “Do you know where your parents are?”, now it could be: “Do you know where (who) your thoughts are coming from?”. Do you?

As Marshall McLuhan famously observed: “The media is the message.” For example, one might consider how corporate media could alternatively have phrased the headline of a related article carried on Bloomberg and Yahoo! this morning: “Argentines Taunt Hedge Funds After World Cup Victory”:

See: http://finance.yahoo.com/news/argentines-taunt-singer-soccer-chants-085448254.html

Or the subtext to The Economist’s July 5th headline that Portes cited in his last paragraph: “Argentine’s debt stand-off reflects a teenage attitude that rules are there to be broken”:

http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21606268-argentinas-debt-stand-reflects-teenage-attitude-rules-are-there-be-broken-luis

These headlines and related articles appear designed to provoke a response that a nation’s entire populace is not only fiscally irresponsible, but even taunts their creditors after refusing to repay their legitimate debts.

I appreciated Portes’ summary of Argentina’s long history of fiscal responsibility until it was broken by elite criminal behavior. I also appreciated his own headline: … “Where Did All That Debt Come From”? Interesting question on so many levels, including who creates and distributes debt-based money?

So what is really going on here?… and why?

“It was difficult to feel much sympathy for the country, which suffered from chronic mismanagement before its default in December 2001 and was to suffer yet more thereafter.”

Inject similar statement for Greece, Zimbabwe, Russian Federation, etc. It’s troubling how so many blame the countries and their “mismanagement” of their currencies and/or economies while taking little notice of the international economic structure that makes these events inevitable. Particularly when helped along by greater economic powers looking to extract rent from nations hobbling along under deeply rooted structural problems. For the list above: perimeter EU economic status of Greece plus classic European racism toward Mediterranean folk, Zimbabwe, as with all other African nations, struggling to redefine itself outside of colonialist paradigms then getting punished for trying plus racism (never acknowledged of course), Russian Federation, Jeffery Sachs and economic restructuring, similar stories for other “failed” economies living under the boot of greater global economic powers. This is why economists need to reintegrate into the realm of politics where markets actually exist. Currencies are politics, politics are markets.

Chauncey, on June 27, you properly referred us to The Confessions of an Economic Hit Man, by John Perkins. A couple of decades from now, perhaps someone will emerge from the shadows and write “Confessions of Another Economic Hit Man”, and answer our questions about Argentina.

The problem we face is an alliance of the finance oligarchs with the national security state and hosts of others that make up the power elite–they are our honorable enemies if we have any sense of decency and thus should be opposed on all fronts. Argentina and all other deeply indebted countries should default at once–that would begin the process of freeing ourselves from a truly nasty ruling class. Here’s hoping Argentina throws a wrench in the works.

Hi Banger. They are our “honorable” enemies?

Let’s not go to the other extreme and eliminate all agency and blame from the countries in question.

Zimbabwe as a poor, misunderstood VICTIM in which patronage system by the one party system enforced through pretty dramatic violence results in a collapse of the economy? And it is not only the “deserving” white colonists who are harmed in this beacon of economic management and social peace!

The Russian kleptocracy?

Hardly models for misunderstood victims.

Paul Singer and company bought Argentina’s bonds at ridiculously low prices–with a strategy that had allowed this financier and others successfully siphon millions from impoverished countries such as Peru, Zambia and Congo.

The ruling of NY Judge Thomas Griesa removed the market risk that assigns a price to those bonds–which is the reason why 92.4 per cent of bondholders accepted a bond exchange with 70 per cent value reduction.

By the magic of a court acting as a collection agency, Singer’s bonds are now worth 100 per cent of their face value.

The vultures never intended to negotiate. They were confident the courts would get them about $1.5 billion for a $48-million investment.

Argentina has clearly said it: it will negotiate a payment under fair and reasonable conditions, which obviously exclude paying what the vultures want, or risk a cascade of lawsuits from the other bondholders claiming same treatment which would inevitably precipitate a default.

The current government has had all along a strategy fundamentally different from previous governments, based on the principle “we have to grow in order to pay.”

From 2003, the country rejected the bitter ‘recession’ pills typically administered by the IMF, and worked instead on reconstructing a devastated economy. As a result of that, today’s debt is 40 per cent of GDP–at the time of the 2001 default, it was 160 per cent.

What the…no, where the f* are the lenders?!? What responsibility does the lender have when lending someone or some country the money in the first place? All this talk about the responsibility of the lendee and how they should pay back, or not pay back, how their system was corrupt, or not corrupt, etc. etc. is quite beside the point. Again, point blank, if a person loaned money to someone, that person, the lender, is responsible for his actions. If the lendee refuses to pay back, the too bad for the lender. The lender must show reasonable action for his leading, else, good for the lendee in getting the lender to perform a bad action.

The main source of the economic problems in the world today is the corrupt and fraud of the lender, not the lendee. Let the lender beware, not the lendee!

Insightful comments here by all. Argentina appears to be a classic victim of John Perkins “Economic Hit Men”, the loan shark crime syndicate, in a debt trap ultimately enforced by imperial courts and military, owned by said syndicate. Vulture Capitalism is an apt description.

Default could bring Perkins’ “jackals” — assassinations and coup by the CIA. Argentina would be wise to find solidarity with Venezuela, Ecuador, Bolivia, and other wise opponents of the Washington Consensus, neoliberalism.

“” The main source of the economic problems in the world today is the corrupt and fraud of the lender, not the lendee. Let the lender beware, not the lendee!””

Amen . This whole problem with modern credit started thousands of years ago where it says in the Holy Bible to paraphrase – ” it is better to be a lender than a borrower “. This assertion is pure nonsense that gives lenders a divine status with zero thought given to critical analysis . Consider the lender that loans one million to someone whom then turns it into one billion several years later while the lender is still only a millionaire . That assertion still haunts the whole of western world finance .

It all boils down to the argument that it was Argentina’s illegitimate military dictatorship that took the money and stole it and/or wasted it on wars against Great Britain and Chile. The current generation of Argentines feels that having to pay that debt is unfair and unjust.

Sure it is. In the next Biblical Jubilee Year debts will be forgiven, slaves will go free and the land will redistributed. Till then, debts have to be paid and contract obligations honoured.

Except when they aren’t and aren’t, of course.

That’s why they had Jubilees. Not all historical relics are ignorant. Economic behaviors are supposed to be for the benefit of human beings, not ideas.