By John Weeks. Originally published at Triple Crisis

Background

Unless you just returned from holiday in some ultra-remote region lacking newspapers, television or internet access (is there such a place?), you are aware that the government of Argentina defaulted on its external debt on Wednesday. A New York federal court provided the immediate cause of the default with a ruling that rendered illegal an agreement reached between the Argentine government and creditors holding over 90% of the country’s external debt.

The principal litigant bringing the case against the government holds less than US$2 billion of the Argentine debt, which by comparison makes a tail wagging a dog seem a credible anatomical interaction. MNL Capital, never lent a cent to the Argentine government (nor to any other). It acquired its one-billion-plus Argentine bonds on the re-sale market, purchasing them at far below face value.

Depending on your source of (mis)information, you will think that this default is 1) the result of an feckless, spend-thrift government failing to accept responsibility for its actions (argued for example, in Forbes), 2) the harbinger of deep economic trouble for the Argentines; and/or 3) the consequence of the predatory evil of vulture hedge funds.

Taking these three in order, they are 1) false, 2) probably false, and 3) true but not terribly important.

The current debt of the Argentine government was accumulated before 2003, much of it under the disastrous presidency of Carlos Menem (forced to resign in 1999) and three short-term successors (Fernando de la Rúa, 1999 to end of 2001; Adolfo Rodríguez Saá, last two weeks of 2001; and Eduardo Duhalde, 17 months to May 2003).

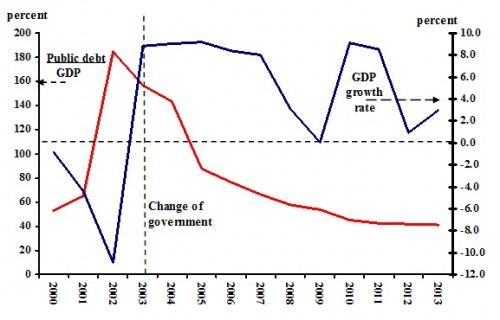

The massive debt accumulation (see chart below) resulted from the hapless attempt to maintain a one-to-one exchange rate between the national currency and the U.S. dollar via a “currency board.” This neoliberal bright idea legally links the amount of national currency in domestic circulation with the U.S. dollars held by the central bank (in this case, the Banco Central de la Republica Argentina).

By the rules of this bone-headed currency “regime,” the national money supply must fall when U.S. dollars flow out of the country (for example, if there is a trade deficit or capital flight). Contraction of the money supply invariably means contraction of the real economy. To avoid this, prior to May 2003, the government (under its revolving door of presidents) borrowed U.S. dollars through sales of public bonds, driving the public debt up to almost 200% of national income (measured on the left hand axis of the chart).

This debt was not accumulated in pursuit of “populist” expenditures by a fiscally irresponsible government. On the contrary, not a single centavo of the debt funded any public service or brought any benefit to people in Argentina. To the extent that the foreign currency acquired by the bond sales stayed in Argentina, it sat idle in the Banco Central. And when this extraordinarily misconceived and mismanaged currency regime inevitably collapsed, it brought the entire economy down with it, a decline of almost 5% in 2001 and 12% in 2002 (read from the right hand axis of the chart), plus runaway inflation that climbed over 100% during these years.

Public debt and GDP growth in Argentina, 2000-2013

Source: World Bank, World Development Indicators 2013.

In the wake of this disaster generated by the neoliberal currency regime, Nestor Kirchner won the presidential election of 2003, succeeded in 2007 by Cristina Fernández de Kirchner, who was overwhelmingly re-elected in 2011. Becoming president after the end of completely discredited neoliberal governments, Kirchner abandoned the “currency board” system and disowned the debt accumulated in a foolish attempt to sustain it.

Why Governments Default

The Argentine debt default this week, which I will discuss in more detail in a subsequent article, demonstrates a general principle–most sovereign debt defaults are not the result of mismanagement or wild spending by sitting governments. Two centuries of debt “refunding” shows there to be at least three major motivations for defaulting on sovereign bonds unrelated to excessive public spending.

First, we find many examples of repudiation of debts because of the dubious circumstances of their accumulation under previous governments, and Argentina is an obvious example. A more extreme example is the cancelling at the 1953 London conference of the external debt of the Federal Republic of Germany (acquired under the Nazi regime).

Second, global economic and political shocks can make it impossible for a government to service its debt (see the excellent 1973 book The Refunding of International Debt, book by Henry Bittermann). Obvious examples are the debt defaults by Latin American governments during the 1930s (due to a sharp fall in primary product prices) and the 1940s (collapse of international trade due to war).

Third, and being played out now in the euro zone, is public sector nationalization of private debts. As I show in my new book, during 2009-2010 the Spain government, previously with the lowest debt-to-GDP ratio of major EU countries, refinanced all its failing banks. This created both an unsustainable fiscal deficit (where before it boasted a surplus) and a public debt it could not finance. None other than the Pinochet regime in Chile had pioneered this particular path to debt disaster in the early 1980s under pressure from the U.S. government (in value the largest nationalization in Chilean history, far larger than anything the socialist Salvador Allende had done).

Augusto Pinochet, the nationalizer of private assets, shaking hands with his patron Henry Kissinger in 1976. Credit: Ministerio de Relaciones Exteriores de Chile, Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Chile license

A Way Out

All this leads to an obvious conclusion–debt default serves as the solution to an otherwise intractable problem, an unsustainable foreign depth. The problem is not default, the problem is the absence of an international mechanism to bring it about in an orderly manner. But the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development has proposed such a mechanism, which I will discuss in another article.

‘Massive debt accumulation (see chart below) resulted from the hapless attempt to maintain a one-to-one exchange rate between the national currency and the U.S. dollar via a “currency board.”’

Several examples of successful currency boards exist. Hong Kong has run a currency board since 1983. In Latin America, Panama has maintained a 1:1 link between its balboa and the USD for over a hundred years. What sank Argentina’s currency board was a drop in real commodity prices during 1999-2001 back to early 1930s levels.

‘Not a single centavo of the debt funded any public service or brought any benefit to people in Argentina.’

Yeah, right! The author must have majored in rhetoric. Just as in other countries, debt was accumulated for a range of purposes. One such purpose was financing a flood of imports. Argentines, finally having the purchasing power of a strong currency for the first time in their lives, went on an acquisition binge. Financing their purchases with sovereign debt did not prove to be sustainable. But one can’t claim that they didn’t benefit from it. That’s just over-the-top rhetoric.

Let me guess Jim: you’re sitting on some of these bonds aren’t you?

The people must suffer for the sake of bond investors! To suggest otherwise is surely a sin!

@Jim Haygood. Exactly! The author never explains why a 1:1 exchange rate is necessarily a bad thing, or even why it is a “neoliberal” idea. (For some, it seems that “neoliberal” is simply a catch-all term of disapproval, like “bourgeois.”) And the author’s statement that none of the debt funded any public service is simply embarrassing.

The only redeeming feature of this article is the author’s confirmation that the “vulture hedge funds” did not play a significant role in this crisis.

“For some, it seems that “neoliberal” is simply a catch-all term of disapproval, like “bourgeois.””

Or “federalism” as a catch-all term for approval of anything, like “exceptionalism”.

Did you ever read the information I linked to in a previous exchange? You seemed so interested.

http://michael-hudson.com/2002/04/the-new-economic-archaeology-of-debt/

I would be very interested in your thoughts about the content. More so I can determine if you are authentically interested in learning or more interested in posturing.

@Alejandro. I read the article you linked to. Thank you. If I understand it correctly, the author wonders whether civilization would have developed in a different (i.e., “more just”) direction if “interest bearing debt” had not played such a significant role. The author seems to view ancient Mesopotamia as a successful example of a such a culture, and, more generally (and of key importance to the author) as a counter to the “modern disparagement” of planned economies.

I am not a devotee of “free market orthodoxy” so I welcome discussion of planned alternatives that might work better than what we’ve been living under recently. But, as the author admits, there are enormous problems with using a 4000-year old culture as an example for policy decisions today, since (as he says) “Mesopotamian social values and their institutional context” were so different from those found today. If we were to focus instead on planned economies of more recent vintage, we notice that these economies have had great difficulty just feeding their populations (see, e.g., Soviet Union, Mao’s China, North Korea, Ethiopia, etc.) Or consider today’s Venezuela or Allende’s Chile – not too encouraging. With these examples in mind, I am greatly skeptical that government central planners are knowledgeable enough to successfully micro-manage today’s modern economies, which not only must feed their populations, but also maintain electricity grids, utilities, Internet, etc. I’m a fan of the so-called “American System” that was in effect for most of 1865 – 1972 or so, as I think this system worked very well for most of its inhabitants, and also helped create many of the social goods and utility structures that we associate with a modern economy. Note that, contrary to what some on the Right claim, this American System was often characterized by massive government spending to help develop key industries and technologies. Anti-usury laws were in effect throughout much of this period as well. But day-to-day decision making re capital investment and allocation was often left to private actors.

I think the author of the article would still disparage the American System, as it does not provide enough centrally administered pricing and central planning. The author takes some cheap shots at what he perceives to be “free market orthodoxy.” Contrary to what the author states, it is not so clear that modern markets are “privatized.” For example, to what extent are today’s stock and bond prices really the result of “free” markets, given how extensively government actors (e.g., the Federal Reserve) now influence today’s markets? Or, consider, when you look closely at the International Monetary Fund’s governance structure, is it a public or private enterprise? (After all, in some sense, it is a “not-for-profit” organization.)

But, turning back to Argentina, it’s striking that we are having this discussion in a thread about Argentina, since Argentina is the only country to attempt a default outside of the IMF’s governance structure. To me, this all went horribly for Argentina, and could have been even worse were it not for the recent commodity boom. I would be interested in your thoughts on this.

Your argument might hold some water, except, Americas government has increasingly over the decades [post WWII – hitting high gear in the 70s] become beholden to what you blithely call – the private sector [actually plutocratic corporatist].

Your counter examples are actually governments attempting to reconcile decades of ideological perfidy and test tube wankery. They can not be allowed to succeed at any level or others might get strange ideals… eh.

Thank you for that well thought out and articulated response. I very much appreciate it. Only honest exchange can be mutually beneficial, even if we don’t agree.

The relevant take-away from Dr. Hudson’ essay is that compounding interest bearing debt, always grows faster than any economy’s ability to sustain and this has been known for a long time. Although I have my reservations on how the terms “public” and “private” are used today, until recently bankruptcy laws were a practical recognition and way to settle unpayable “private” debts. No such forum or platform exists for sovereign debt, which is why we’re discussing it in a thread about Argentina. Despite there being no “official” forum, Argentina successfully re-structured their debt with over 90% of the bond-holders except for the so-called “hold-out”. The “hold-out” turns out to be a Vulture with a track record of predatory financial behavior and no track record of “investing” in anything of actual value.

@Alejandro. We may agree on more than it might appear at first glance. The U.S. could very well find itself in a position similar to Argentina’s, if it can’t figure out a way to reign in its TBTF banks, and prevent these banks from continuing to shift their enormous debts onto the public fisc. How these banks ever got so large, and why various “rent-seeking” industries that create little or no value ever became so powerful, is a problem that seems to have originated somewhere around 1972 – the time Nixon completely eliminated the dollar’s link to the gold standard. (By contrast, the late 1800s in the U.S. were characterized by a near-fanatical adherence to the gold standard.) In any event, whereas Argentina chose to restructure outside the IMF, the U.S. effectively might find itself in the same position if it’s troubles grow too large for the IMF to solve – i.e., it will have to figure out how to restructure outside of the IMF! But that might be a discussion topic for another day. Cheers!

The Argentinian currency peg was a bad thing because it is an implied promise made to the holders of Argentinian pesos that cannot be kept by the promisor. Only when holders of the peso believe that it

is roughly equal in value to a US dollar now and in the future can this system possibly work. Unfortunately the creators of the currency board don’t hold all of the pesos, or even most of them. Why do they make the promise then? Because, in the short run, while this belief holds, insiders can sell pesos and buy dollars and profit from the inevitable collapse. The currency board is intended to CREATE PESO BUYERS AND BELIEF IN THE ARGENTINIAN ECONOMY. While there are peso buyers, economic activity in Argentina increases and the population is happy. The end.

Dude says: “Argentines, finally having the purchasing power of a strong currency for the first time in their lives, went on an acquisition binge.” He makes it sound like the basement at Filenes down there in Buenos Aires. Dude is spouting the abusive language of the creditor. I was down there for a couple of weeks in 2000, and saw absolutely no evidence of runaway consumerism. Dude just cuts and pastes abusive language from one post to the next. All in a day’s work at the think-tank.

Yeah, they call it a tank because people are in it.

That remote place you wonder about Yves? It exists, and it is called the US Prison System.

Are you suggesting that being incredibly intelligent, honest and forthright with knowledge is a crime? That is truly a despicable comment to taint this thread with. Fail2Plan MIGHT be a better description of this whole sovereign debt saga on all sides…it has exposed another of the many things terribly wrong with the current financial system and judicial system as well (and NOT for the reason you imply!). Yves Smith has been a stalwart beacon of not just exposing the REAL criminal activity but exploring solutions that offer hope for a better world for everyone and that includes whoever you happen to be. So in the meantime, unless you have anything valuable to contribute, go fuck yourself!

Argentina is NOT in deafault, you moron!

The debt – accumulated since Washington-imposed dictatorship – was successfully restructured with 92% of creditors, but then judge Griesa forbid Argentina to keep paying (!), so to pay THESE vultures in particular first and more! They acquired the debt for a junk price, but want to collect the whole price of it and more!

Just don’t pretend to be “impartial” and much less “progressive”. For those who want the information from the other side http://www.opednews.com/Quicklink/Vulture-Funds-by-Guglielmo-Tell-Argentina_Hedge-Funds_International-Monetary-Fund–IMF_Market_Fundamentalism-140805-219.html .