Yves here. Most people outside the financial services industry don’t realize that many countries in Europe have banking systems that are obviously riskier than America’s. A crude metric of vulnearbility is the size of banking industry total assets compared to GDP. Iceland prior to its meltdown came in at around 900% of GDP. The UK is roughly 600%, which is one big reason why beating back the threat of a Scottish exodus was so critical. Unexpected disruption could prove hard to contain.

It should be noted that looking at the size of assets in the banking system makes the US look better than it really is. America has gone furthest of any advanced economy in moving what were once bank businesses into the capital markets. What the crisis exposed is that banks were exposed to many of those risks and that letting certain type of non-bank financial players founder was deemed to be just as impermissible as letting a major bank or then investment bank go down. For instance, banks had supposedly off balance sheet entities, like structured investment vehicles and credit card securitizations, where in practice they were exposed to losses. And the officialdom rescued various markets, which included supporting non-bank actors, like the repo market (money market funds), credit default swaps (AIG) and residential mortgage backed bonds (in that case, from legal liability, and the parties saved included mortgage servicers).

This post takes a more rigorous look at the countries most at risk in the event of a systemic shock. The UK and France look the most wobbly. The post also singles out banks like ING that the authors contend are too big to be saved. While some journalists and analysts have raised these issues (Deustche Bank come up regularly), this analysis may prove harder to ignore.

By Robert Engle, Michael Armellino Professor of Finance at New York University Stern School of Business, Eric Jondeau, Professor of Finance at HEC, University of Lausanne and Michael Rockinger, Professor of Finance at HEC, University of Lausanne. Originally published at VoxEU

The Global Financial Stability Report of the IMF (2009) defines systemic risk as “a risk of disruption to financial services that is caused by an impairment of all or parts of the financial system and that has the potential to cause serious negative consequences for the real economy”. With the recent financial crisis, interest in the concept of systemic risk has grown. The rising globalisation of financial services has strengthened the interconnection between financial institutions. While this tighter interdependence may have fostered efficiency in the global financial system, it has also increased the risk of cross-market and cross-country disruptions.

Measures of systemic risk are generally based on market data. Two questions may be answered with such data because historical prices contain expectations about future events.

• First, how likely is it that extreme events will occur in the current financial markets?

• Second, how closely connected are financial institutions with one another and the rest of the economy?

Obtaining the answers to those questions is at the heart of most of the recent research on systemic risk. The shape of the distribution of financial returns and the strength of the dependence across financial institutions are both essential to determine the speed of the propagation of shocks through the financial system and the level of vulnerability to such shocks.

Focus on Financial Externalities

In the aftermath of the recent financial crisis, the literature has focused primarily upon externalities across financial firms that may give rise to liquidity spirals. In particular, it became clear that network effects must be addressed to fully capture the contribution of banks to systemic risk. Thus, these measures of systemic risk consider the risk of extreme losses for a financial firm in the event of a market dislocation. Acharya et al. (2012) and Brownlees and Engle (2012) have proposed an economic and statistical approach to measure the systemic risk of financial firms. Following Acharya et al. (2012), the externality that generates systemic risk is the propensity of a financial institution to be undercapitalised when the financial system as a whole is undercapitalised.

In this context, there are likely to be few firms willing to absorb liabilities and acquire the failing firm. Thus, leverage and risk exposure are more serious when the economy is weak. This mechanism can be captured by the expected fall in the equity value of each firm conditional on a weak economy. Then, the capital shortage for each firm is considered the source of a deadweight loss to the economy. In the econometric methodology proposed by Brownlees and Engle (2012) for US financial institutions, the model estimates the capital shortage that can be expected for a given firm if there is another financial crisis. The model is composed of a dynamic process for the volatility of each firm’s return and its correlation dynamic with an overall equity index. Innovations are described by a non-normal (semi-parametric) joint distribution that reflects the sensitivity of the firm’s return to extreme downturns in the equity market.

European Institutions

In the case of European institutions, there are several additional issues beyond the aforementioned components to measure the risk exposure; for a given firm, a financial crisis may be triggered by a world crisis (such as the Subprime Crisis), a regional crisis (such as the European debt crisis), or even by a countrywide crisis (such as the Greek debt crisis for Greek banks). Thus, a natural extension of the previous models is a multi-factor model, where several elements may jeopardise a financial firm’s health. Furthermore, the parameters of the model, in particular the sensitivity to market movements, may change over time. This, in turn, requires a model that allows for time-varying parameters. In this paper, we adopt the Dynamic Conditional Beta approach recently proposed by Engle (2012), in which a Dynamic Conditional Correlation (DCC) model is used to estimate the statistics that are required to compute the time-varying betas. Another issue with non-US institutions arises from the asynchronicity of the financial markets. A world crisis (for instance, initiated in the US market) may affect other regions either the same day or one day later. We design a specific econometric model to address asynchronous markets.

New Evidence

Our empirical analysis is based on a large set of approximately 400 European financial firms, which includes all banks, insurance companies, financial-services firms, and real-estate firms with a minimum market capitalisation of one billion euros and a price series starting before January 2000. We investigate several aspects of systemic and domestic risks among European financial firms. In particular, we evaluate the relative contribution of countries and individual firms to the aggregate systemic risk in Europe. Our approach allows us to explicitly identify global systemically important financial institutions (G-SIFIs), using the terminology of the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, by estimating a firm’s capital shortfall in case of a worldwide shock or a Europe-wide shock. We also identify domestic systemically important financial institutions (D-SIFIs) by investigating the impact of the rescue of a firm on the domestic economy.

At the end of the study period (31 July, 2014), the total exposure of the 100 most systemically risky firms was 810 billion euros.

• The countries with the highest levels of systemic risk are France and the UK.

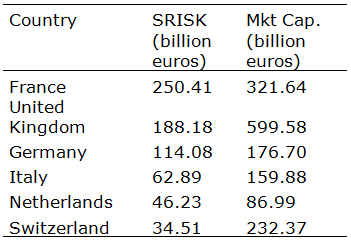

These two countries contribute to approximately 55% of the total exposure of European financial institutions (Table 1).

Table 1. Systemic risk by country

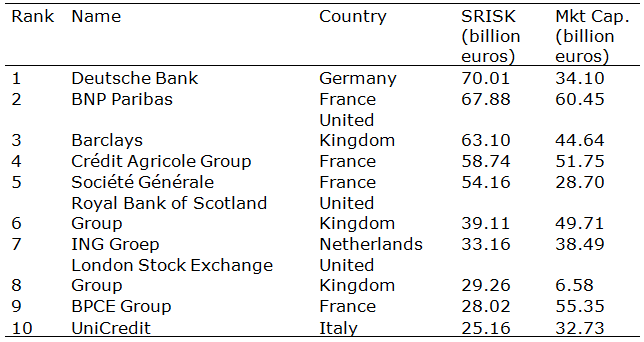

• The five riskiest institutions over the recent period have been Deutsche Bank, BNP Paribas, Barclays, Crédit Agricole, and Société Générale.

Together, they bear almost 314 billion euros, i.e., 39% of the total expected shortfall in the case of a new financial crisis (Table 2).

Table 2. Systemic risk by financial institution

• Even after correcting for differences in accounting standards, the total systemic risk borne by European institutions is much larger than the one borne by US institutions.

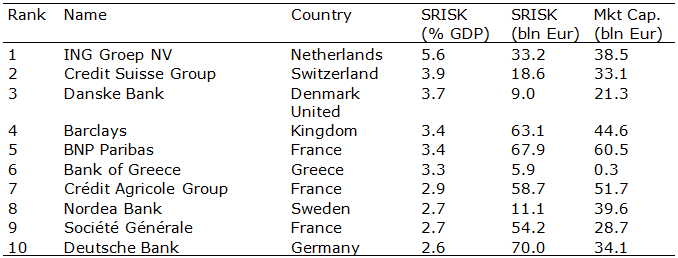

For certain countries, the cost for the taxpayer to rescue the riskiest domestic banks is so high that some banks might be considered ‘too big to be saved’.

• For ING Group in the Netherlands, Credit Suisse in Switzerland, Danske Bank in Denmark, Barclays in the UK, BNP Paribas in France, or Bank of Greece in Greece, the systemic risk measure represents more than 3% of domestic GDP (Table 3).

Table 3. Systemic risk by financial institution in % of GDP

Concluding Remarks

The European Banking Union will start soon. At the end of this year, the ECB will be the single supervisor of the largest banks of the Eurozone. Given the uncertainty about the quality of bank’s balance sheets, the ECB has undertaken an Asset Quality Review (AQR) and stress tests to evaluate the potential capital shortfall of large banks, including domestic systemically important banks. The AQR and stress tests are relatively expensive and time consuming processes, which require a lot of inputs from banks. It will be interesting to compare the results of the AQR with our ranking. Furthermore, our methodology can be used to measure how bank conditions have changed over time and serve as a monitoring system as the Eurozone banking system evolves.

Authors’ note: Systemic risk measures based on the methodology described in this paper are available on the CRML (Center for Risk Management — Lausanne) website at http://www.crml.ch.

See original post for references

Perhaps use Mark Blyth’s term, “Too Big to Bail” ?

Print, baby, print!

So in other words throwing $30 Trillion at these failing banks didn’t work? But they promised..

“While this tighter interdependence may have fostered efficiency in the global financial system, it has also increased the risk of cross-market and cross-country disruptions.”

Indeed, as some economists(*) have argued, it’s just this extreme “efficiency” of various financial markets which increases their inherent riskiness. The financial markets were significantly less risky when, previously, they operated with significantly less “efficiency” –as defined by certain financial “Quants” and econometricians. ( (*)See Ha-Joon Chang’s critiques and analyses, for an example.)

I believe that the shock of 2008 caused a tightening of financial oversight and cooperation by the big corporate, state and international actors. In the U.S. the financial sector held a gun to the head of the POTUS (GWB) of that time and said “pay-up or else” and the POTUS and the rest of the USG surrendered and, it seems, allowed the very criminals that engineered or blundered into the crisis (I suspect it was a bit of both) to take advantage of the results. But, it seems that part of this agreement was that the financial sector would be more active in governing itself to avoid a future catastrophe by cooperating in forming a network type of structure that would be put in place to avoid severe fluctuations in the markets, i.e., a “plunge protection team” that encompassed all the actors. Within that structure banks could speculate and game the system but shoulda crisis erupt the whole network would try to absorb the shock so that public regulation of the industry would not become the dominant actor is setting limits.

Now, I’m sure many who write here know the situation much better than I do know that sovereign and international funds do have that role to play and do cooperate and I know that major financial institutions in the U.S. are now virtually government entities (in the sense they are above the law and allowed to not be subject to most market forces)–any thoughts?

It seems as if the entire financial “industry”, from banking to insurance to real estate is a racket, just like war.

We have global money trading that is 60 times greater than the value of global goods trade. There is one or two qaudrillion dollars of financial bets outstanding in derivatives. Almost all of it is done with borrowed money.

First, how likely is it that extreme events will occur in the current financial markets?

100% The financial criminals are still in charge. Their punishment for causing the GFC? Multimillion dollar bonuses for obtaining “maximum extractable value” from society. They will do it again because money.

Is there a hilarious circularity to this reasoning? the model calibrates sensitivity of bank’s returns to extreme downturns in equity markets. When banks’ gross mismanagement causes the downturns it’s like the model has created a tube running from butt to mouth measuring health sensitivity to dietary shocks.

Yeah Lambert the show was packed. A handful of serious bearded dues with cameras too! But no photographer’s vests. It’s almost like showing up at the Yankee game with a hat, jersey and glove — when you’re 32 years old. hahaha

I read lots in the blogosphere that is just defeatist moaning about the state of affairs with no call to do anything about it. But at least your mouth-to-orifice image brightened my day. It’s an image for our times.

We can extend your metaphor to cover many aspects of our sick world. People see narcissism deified on social media…so they take selfies of themselves looking at other people’s selfies in a self-referential circle jerk. The military invades and bombs countries looking for enemies and oh what a surprise, it then finds lots of them, for sure. More fecal matter then enters the loop and just stays there, cycling around.

I think I’ll go retch now.

Unlike Capitalism, Globalization is a Ponzi/Pyramid Scandal

http://wh.gov/iqZ24

So the answer to liquidity spirals due to out of sync markets is higher capitalization of systemically important institutions. And there are over 1.2 quadrillion in derivatives floating around the world. And at least here, those derivative contracts are in the depositary of all the big banks. And it is understood they are better than money itself because the law also dictates that those contracts get bailed out first. So it is doubly curious that bail-ins threaten just money on deposit; but not derivative contracts on deposit. What’s the point of hoarding capital to cover a liquidity spiral when the banksters continue to write derivatives (elite money) at record pace? What bank has the capacity to maintain capitalization to cover its derivatives? In a world gone dead, it is only the derivative trade that is keeping banks liquid. Or I guess the other solution is to design markets that are never out of sync by providing syncronicity insurance. Now there’s an insurance policy that might work – like a big mutual fund of all profits from derivatives set aside for a certain length of time to maintain the capital to cover all of the banksters systemically important mistakes and extortion rackets.

Financial risk always exists but I think that risk analysis should be accompanied with other analyses to see not only what kind of bank actives bear risk but what kind of economic activity, is the counterparty of these risky assets. That is important to evaluate the need to rescue a bank and the benefits that such rescue has on the country where it resides. For instance, Bank of Greece, (3,3% Greece’s GDP) migth have a very different risk pattern compared with Deutsche Bank (2,6% Germany’s GDP). I guess that most BoG actives have greek counterparties and the risks derive from the depression. On the other hand Deutsche Bank riskier actives migth include a lot of foreign counterparts (from US subprime lenders or Spanish titulizaciones to whatever complex financial product recently invented). I believe that in economic terms you migth obtain more benefits per monetary unit spent by rescuing Bank of Greece than rescuing Deutsche Bank.

In other words, for a complete risk assesment the economical impact of the bank in the real economy should be also analysed. What kind of activities are supported by each bank and what are the benefits that this activities have. Then, you decide what support you could provide to each bank in case of failure. You could consider that some banks have to be guaranteed 100% and others, let’s say 50%.

And yet history has shown that these banks will be bailed out, regardless of how much pain it will cause the rest of the country. Iceland, with an astounding 900% asset-to-GDP ratio still chose to impoverish its citizens rather than curb its banks. They went from having one of the highest per-capita GDPs in Europe to having difficulty with food imports. All in the name of saving the banks.

Greece has similarly, under instructions of the Troika and in the name of financial stability, put its citizens through an unprecedented depression that will likely reverberate for generations to come.

So while this study is interesting as an academic exercise, it does nothing to answer the question of whether these banks will actually be saved. That answer is obtained by studying current political winds and historical decisions, and both give a resounding “Yes!”

Ultimately, this will go on through successive crises until the guys with the guns decide to stop backing the current international finance elite. And what comes next is likely going to make Disaster Capitalism look like a sunny Sunday picnic. Just look at that situation in Ferguson MO. We’re talking about a collection of people who want nothing more than to cleanse the nation of peaceniks, undesirable elements and do-gooders.

The pain of letting one of these banks fail is why they are considered too big to fail. That is why they need to be dismantled prior to becoming too big in the first place. If ANY of the European banks in the list published in the article were to fail, without being “bailed: out by whatever sovereign or collective of sovereigns with jurisdiction over it, the equivalent of an economic supernova would occur, with global consequences. Very few people really grasp this point. Most of what you experience as an economy around you would collapse for a good while before re-establishing it in whatever new form emerges. Some may see this as painful but good thing to get us of the accelerating debt treadmill were all on (Citizens/Governments/Banks). BUT, do not be fooled it would be an astoundingly painful process. Remember underneath the skirt of BNP Paribas, or Wells Fargo for that matter lies millions of home loans, millions of business loans, millions of credit card accounts, all supposedly risk neutralized via derivatives swaps with hundreds of other similar banks. All in a domino clusterf***. It may be a cold comfort to imagine that what is required is just the will to thrash some unscrupulous bankers and their nefarious overlords and viola righteousness is restored. In reality there is no superman solution, because superman is a fairytale. The closer you get to the academic, regulatory and political power players that deal with these things the more fear you will detect. And not because they lack levers of control over these things, BUT moreso because they realize just how massive and unstable these bombs are.

Did they study the Austrian banks? I can’t see any data. (Austrian banks acquired many banks in their former empire.)

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/09/01/austria-east-idUSL5N0R216S20140901

“Austrians say the party is over for business in Eastern Europe”

“…a Hungarian law forcing banks to compensate customers for mispriced loans.”

http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/09/04/hungary-banks-loans-idUSL5N0R51VY20140904

“Hungary’s banks must reimburse clients by February -lawmaker”

When you read in western press that Hungarian leaders are “undemocratic”, “dictators” etc. – you know why.

Ah, maybe that is why the US has imposed sanctions on some Hungarian government leaders, preventing them entering the US? Allegedly this is because of corruption. So is the ‘crime’ too much corruption or not enough?