Yves here. We’ve discussed the fracking bubble intermittently, particularly that many of the valuations ascribed to shale gas wells don’t reflect how short their production lives really are. This report by Steve Horn of DeSmogBlog focuses on a related result from the same set of unrealistically high production assumptions: that overall fracking output forecasts are likely to prove to be high.

By Steve Horn, a freelance investigative journalist and past reporter and researcher at the Center for Media and Democracy. Originally published at DeSmogBlog

Post Carbon Institute has published a report and multiple related resources calling into question the production statistics touted by promoters of hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”).

By calculating the production numbers on a well-by-well basis for shale gas and tight oil fields throughout the U.S., Post Carbon concludes that the future of fracking is not nearly as bright as industry cheerleaders suggest. The report, “Drilling Deeper: A Reality Check on U.S. Government Forecasts for a Lasting Tight Oil & Shale Gas Boom” authored by Post Carbon fellow J. David Hughes, updates an earlier report he authored for Post Carbon in 2012.

Hughes analyzed the production stats for seven tight oil basins and seven gas basins, which account for 88-percent and 89-percent of current shale gas production.

Among the key findings:

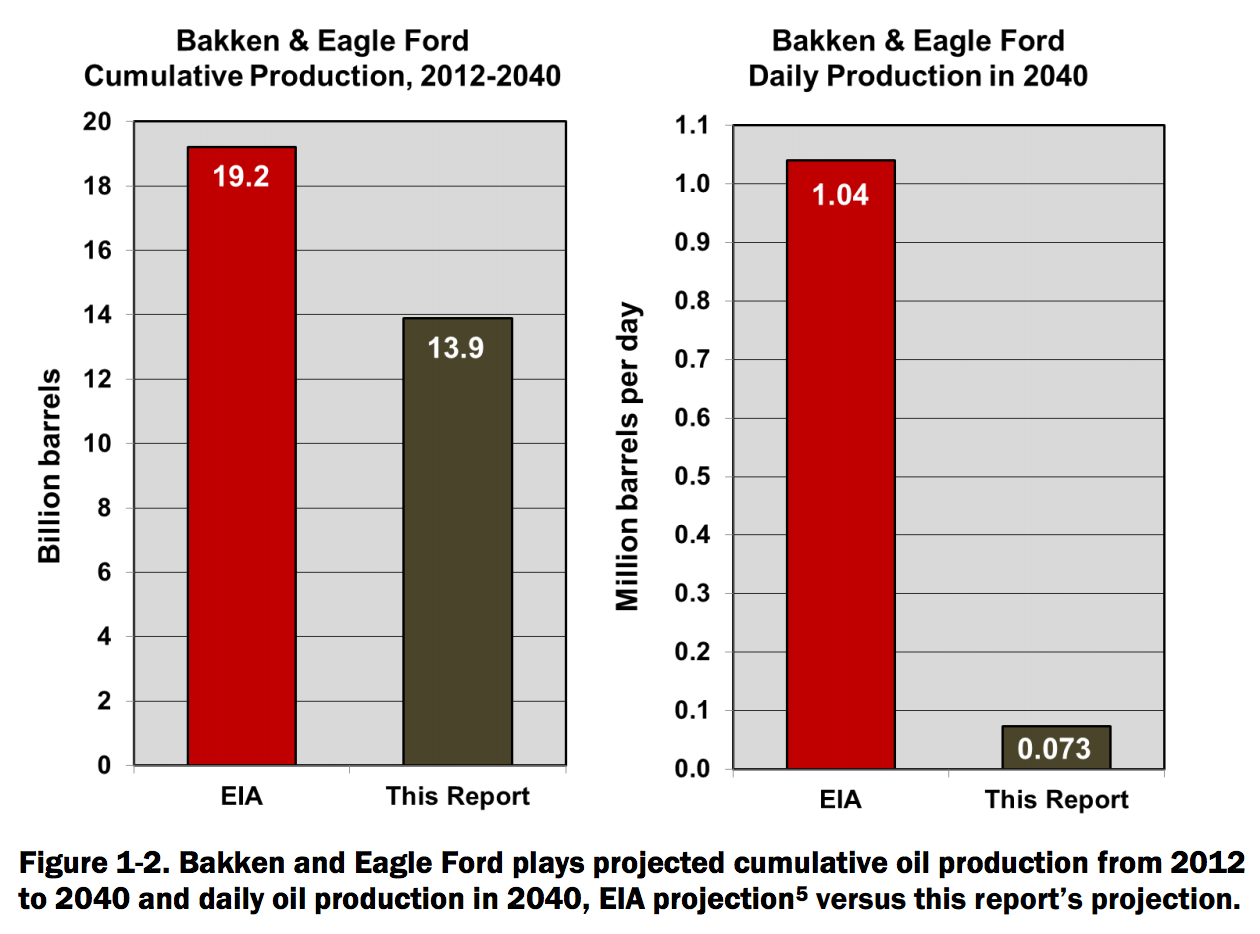

-By 2040, production rates from the Bakken Shale and Eagle Ford Shale will be less than a tenth of that projected by the Energy Department. For the top three shale gas fields — the Marcellus Shale, Eagle Ford and Bakken — production rates from these plays will be about a third of the EIA forecast.

-The three year average well decline rates for the seven shale oil basins measured for the report range from an astounding 60-percent to 91-percent. That means over those three years, the amount of oil coming out of the wells decreases by that percentage. This translates to 43-percent to 64-percent of their estimated ultimate recovery dug out during the first three years of the well’s existence.

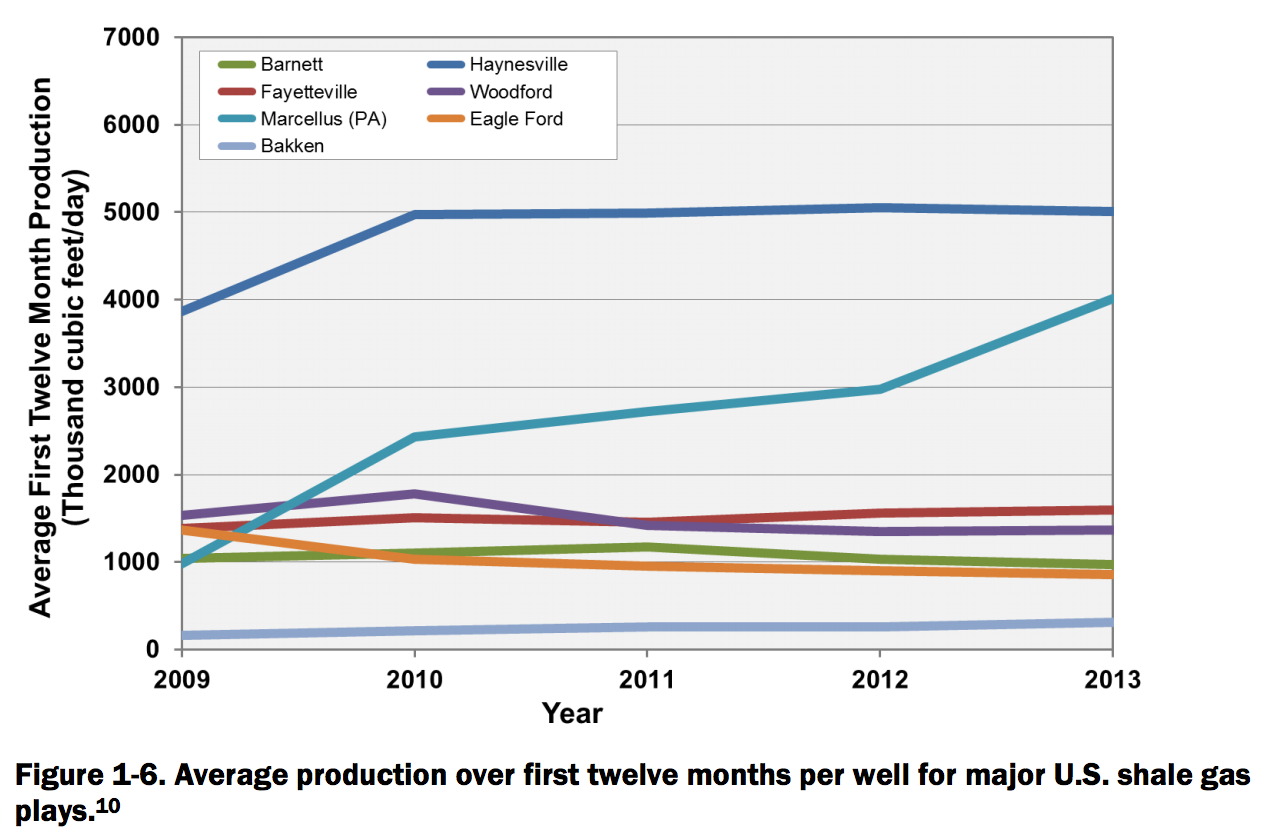

-Four of the seven shale gas basins are already in terminal decline in terms of their well productivity: the Haynesville Shale, Fayetteville Shale, Woodford Shale and Barnett Shale.

-The three year average well decline rates for the seven shale gas basins measured for the report ranges between 74-percent to 82-percent.

-The average annual decline rates in the seven shale gas basins examined equals between 23-percent and 49-percent. Translation: between one-quarter and one-half of all production in each basin must be replaced annually just to keep running at the same pace on the drilling treadmill and keep getting the same amount of gas out of the earth.

The report’s findings differ vastly from the forward-looking projections published by the U.S. Energy Information Agency (EIA), a statistical sub-unit of the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE).

The findings also come just days after Houston Chronicle reporter Jennifer Dlouhy reported that in a briefing over the summer, EIA Administrator Adam Sieminski told her it was EIA’s job to “tell the industry story” about tight oil and shale gas production.

“We want to be able to tell, in a sense, the industry story,” Sieminski told Dlouhy, as reported in the Chronicle. “This is a huge success story in many ways for the companies and the nation, and having that kind of lag in such a rapidly moving area just simply isn’t allowing that full story to be told.”

The independent story, though, opens up a window to tell a different tale.

“The Department of Energy’s forecasts—the ones everyone is relying on to guide our energy policy and planning—are overly optimistic based on what the actual well data are telling us,” Hughes — a geoscientist who formerly analyzed energy resources for over three decades for the Geological Survey of Canada — said in a press release about the reporting’s findings.

By asking the right questions you soon realize that if the future of U.S. oil and natural gas production depends on resources in the country’s deep shale deposits…we are in for a big disappointment in the longer term.”

Sweet Spots” and the “Drilling Treadmill”

According to Hughes’ number-crunching, four of the top seven shale gas fields have already peaked: the Haynesville, Barnett, Woodford and Fayetteville. But three of those are actually doing the opposite and increasing their production: the Marcellus, Eagle Ford and Bakken, though the latter two are primarily fracked oil fields.

Further, the report points to the phenomenon first discussed in the original Post Carbon report back in 2012: that of the “drilling treadmill,” or having to drill more and more wells just to keep production levels flat. The report argues that drillers hit the “sweet spots” first to maximize their production, do so for a few years until production begins to decline terminally, and then start drilling in spaces with less rich oil and gas bounties.

A case in point: Post Carbon projects the Bakken and Eagle Ford Shale basins — the two most productive oil plays — will produce a minuscule 73,000 barrels of oil per day in 2040. EIA, meanwhile, says 1.04 million barrels per day of oil will be pumped from the ground at that point.

Graphic Credit: Post Carbon Institute

One of the keys to the so-called ‘shale revolution’ is supposed to be technological innovation, making plays ever-more productive in the face of the steep well decline rates and the move from ‘sweet spots’ to lower quality parts of plays,” wrote Post Carbon in an introduction to the report for members of the media. “But despite years of concerted efforts, average well productivity has gone flat in all the major shale gas plays except the Marcellus.”

The Bakken and Eagle Ford serve as Exhibit A and Exhibit B of the mechanics of how the “sweet spot” phenomenon works in action.

Field declines from the Bakken and Eagle Ford are 45% and 38% per year, respectively,” wrote Hughes in the executive summary. “This is the amount of production that must be replaced each year with more drilling in order to maintain production at current levels.”

For gas, it’s the same story, centering around “sweet spots” and the “drilling treadmill.”

Graphic Credit: Post Carbon Institute

EIA Guessing at Numbers and Figures?

So where do the EIA’s rosy statistics originate? Post Carbon Institute posed its own questions directly to the EIA, while also saying one has to look at the difference between proven and unproven reserves to understand EIA’s data.

Shale gas producers and the EIA report ‘proved reserves,’ a definition with legal weight describing hydrocarbon deposits recoverable with current technology under current economic conditions,” they write. “The EIA also estimates ‘unproved technically recoverable resources’ which have loose geological constraints and no implied price required for extraction, and hence are uncertain.”

Also implicit in the rosy numbers and figures is that cash will continue to be injected into capital-intensive shale gas and oil production operations.

So far, the industry and its financiers have received a blessing from the U.S. Federal Reserve: zero-percent interest rates to obtain junk debt bonds to finance fracking since 2008. But with the Federal Reserve considering hiking rates, economics could change quickly on the feasibility of continued unfettered shale oil and gas extraction.

Hughes said his findings are based on “best case scenarios” and rule out external conditions that could reverse the drilling treadmill, including hiked interest rates.

Other factors that could limit production are public pushback as a result of health and environmental concerns, and capital constraints that could result from lower oil or gas prices or higher interest rates,” he wrote. “As such factors have not been included in this analysis, the findings of this report represent a ‘best case’ scenario for market, capital, and political conditions.”

False Premises, False Promises

The Obama Administration’s climate and energy policy rides on the assumption of decades more domestic oil and gas obtained from fracking.

Indeed, the shale boom has created a revolution of sorts for corporate interests across the supply chain from the world of plastics to manufacturing to the pipeline business to liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals and far beyond, creating something akin to a “complex.”

Asher Miller, executive director for Post Carbon Institute, said the enthusiasm in what to some may seem like a nearly infinite future of shale oil and gas is a “false premise” that has manufactured “false promises.” Hughes echoed these sentiments in the report’s conclusion.

The assumption that natural gas will be cheap and abundant for the foreseeable future has prompted fuel switching from coal to gas, along with investment in new generation and gas distribution infrastructure, investment in new North American manufacturing infrastructure, and calls for exporting the shale gas bounty to higher-priced markets in Europe and Asia,” he wrote.

Given these assumptions—and the investments being made and planned because of them—it is important to understand the long-term supply limitations of U.S. shale gas,” Hughes suggests.

The regular, almost weekly reports about LNG and natural gas from the Marcellus Shale, indicate a realistic assessment of the amounts that can be recovered measured in decades. The Philadelphia Inquirer has any number of writers covering various angles of this gas boom. PA has over 7,000 gas wells operating.

And the rush to invest $10s of millions in one project after another from the extraction site to the ports of Philadelphia and North Jersey, as well as Delaware seem to be predicated on returns that will span many decades. From pipelines to LNG storage sites and port terminals on the rivers, this type of investment is not made without assurances of long term returns. Because of the coal seams in PA, the certain geological survey knowledge about gas has been held for a long time by land barons from the era of King Coal. Much rural land was conveyed without subsurface rights to minerals, water, oil and gas, etc.

Held in trust by the city of Philadelphia Board of Trusts, which includes a small fortune in holdings from the Stephen Girard Estate, are thousands of acres of land which include the underground mineral rights. This is controlled by the city of Philadelphia. Additionally, there are thousand of acres of state lands set aside for conservation, hunting, fishing and some small scale logging. Currently, from about 10 gas extraction wells on state park and game lands is enough monthly gas production equal to the monthly usage of the entire city of Philadelphia, residential and commercial. The city owns the PGW, the Philadelphia Gas Works, which is a over 170 years old and a complete monopoly for natural gas. A deal to sell PGW for $1.86Bil was just killed in a city council vote yesterday to the anger of the mayor, among others including JP Morgan.

There is such a high level of activity from the PGW sale, to the build out of pipelines to North Jersey port oil and gas terminals, and the same for port facilities along the Delaware in PA, NJ and Delaware, that you can only assume that Marcellus is a deep and long lasting play to attract so much money and political re-alignments based on lobbying state, county and local laws on zoning control. But even if the Marcellus Shale is the real deal, it is not part of the energy future for America in the least bit. All of the activity is to move this gas to port for export to Europe for plastic factories and maybe a pipeline extension to connect to Gulf plastic factories. Because Marcellus is a high grade natgas full of butane, ethane and propane, it will not be sold as fuel for heat or burn to make electricity. It will be shipped out of the country for manufacturing plastic at a higher price than the simple fuel.

Instead of producing a so called “Silicon Valley of Energy” in the Delaware River Valley as the hucksters promote, we will be left as little more than a spigot at a port terminal where the raw material will be sent to factories with the higher paying jobs. So, as the promise of USA-Petro-Power-State seems to be a paper tiger and the one real field of gas in PA is going to be sold to the highest bidders outside of America, what will we be left with when the well runs dry? Just ask the Pennsylvania coal towns buried in hills of slag from long dead mining operations.

http://articles.philly.com/2014-10-13/business/54933576_1_marcellus-shale-mariner-east-propane

I’m glad to hear that the city council turned down the sale of PGW. I hope they continue to because that is an asset that Wall Street would love to have and the city needs it more than they do.

You refer a couple of times to the investors, companies, etc., having a realistic outlook on future production as evidenced by the level of investment in infrastructure to store, transport, and export the Marcellus gas. I’m not so sure they do. I think they are using EIA kinds of numbers (inflated) to justify the activity while making money off the financial side of the deals. If Marcellus can’t produce enough in ten years to export profitably the current investors, etc., don’t really care. They will have made their money.

I agree with the rest of what you say, especially the end game of export to higher priced users. I just think the Marcellus is going to end up much like the rest with intense production declines, it’s just taking a little longer to appear.

So this pipeline would be to bring NY gas to the coast and not PA gas to NY?

As cited here and elsewhere, the up-front costs of primary plays (capex, permits, materials, payrolls, etc.) have been financed by ZIRP-fueled junk bonds and other financialization mechanisms (tax incentives, tax credits, depletion allowances, creative accounting, etc.). In other words, no big operator is putting full-metal corporate skin in the game.

Also, the big companies that field these plays have already done as much as they can to externalize environmental, social, and political costs by buying favorable legislation, media coverage, and junk science. Where possible, they’ve deployed lots of money and lobbyists to insulate themselves against popular backlash, regulation, and negative reportage.

But. I’d be amazed if the primary players aren’t already looking for an exit strategy, given the short life of the average shale/tight/lateral extraction gambit. And it seems to be happening: the big companies are selling off chunks of current operations to smaller, dumber operators, or burying the money-losers under layers of corporate subterfuge. Or, repackaging these sputtering plays in various opaque ways (thanks, Wall Street and the PE industry!), for consumption by ignorant, self-deluding investors with big wallets.

Call me cynical, but I suspect that the big operators are going to walk away from what’s clearly an unsustainable bubble by offloading all the bad stuff onto bondholders, taxpayers, limited partners, and lower-tier operators. The sooner, the better.

At least the lawyers, traders, and bankruptcy trustees will keep getting rich. *Whew!* Crisis averted.

Whether or not you’re a fan of the Post Carbon Institute’s agenda, Hughes is credible and this report is a keeper. File it with past NC posts on work by Art Berman and Gail Tverberg, and you’ll have a good handle on best current thinking wrt impact on US oil and gas supplies from the shale plays.

I agree entirely with Hughes that policy makers shouldn’t swallow whole the cocksure cornucopianism currently emanating from the likes of the WSJ editorial page. Also premature, IMO, are confident assertions that it’s all a scam. Of COURSE the producers are hyping the potential of their holdings – they’ve been doing it for 150 years. That doesn’t answer the question of what supplies will actually be available at affordable prices. You have to wait for the rocks to tell you. And they talk real slow.

You’ve got to love Americans. In the face of overwhelming evidence that a Zero Carbon economy must happen, and soon, we ramp up in our sweet spots: malinvestment, fraud, ponzi schemes, delusional thinking, and collective suicide. Viva death, suckers.

Trying to keep my cynical, ‘follow the money’ world-view in check, I am still trying to find honest information regarding production declines being the end of first-years-production extremely generous tax breaks, versus actual production declines. The cynic in me says well production declines occur on the first day of year three of a well (at least in North Dakota/ Bakken). You’ve taken max tax benefits for the two first years of production, recouped drilling expenses–you have the minerals under your control, (held by production), so you simply turn back the spigot a bit, and keep upward price pressure going. I’m still trying to figure out why oil is dropping… objectively, world events should be shooting it through the roof. And folks wonder why investors sit on the sidelines… price discovery versus opacity of ‘true, verifiable facts’. Criminy

Production declines occur on day 1, not day 1 of year three. That’s the nature of the beast. In fact, we would more accurately call oil and gas “production” as oil and gas “depletion” because we’re not actually producing those hydrocarbons — nature did that over eons — we’re depleting them. And that depletion starts at day 1.

This is not just a semantical statement. Productivity of wells is always highest in the beginning and then drops off. The difference with shales is that the drop off is precipitous. The decline rates are steepest in the first year, then second, and so forth. If you look at the charts in the report, you’ll see those trends clearly. So this has nothing to do with tax incentives; it’s geology.

Words and semantics matter here… production does NOT necessarily decline from day one, it can be and is all over the map, depending on enhanced primary, secondary, tertiary recovery techniques. Depletion is inevitable with a finite resource. The question I raised but nuance I obviously failed to elucidate: once a well is successfully drilledand producing, is there not a competition between need to pump/ sell/ generate revenue, versus the greed/ conservation of resource incentive to hold back on production?. At least, that’s the question I have… seems to me if you are a cash-rich producer, you can in fact choke back on production? And if that is the case, maybe declining production is in fact a contrivance— and I do know that the North Dakota tax laws do have a very real incentive to produce as hard as possible in years one and two, as the taxes are very light, to allow for recovery of drilling expenditures.

I’m not sure how this relates to the post, but in the last 3 months, most stocks in every sector of the oil industry are down at least 20%, as oil itself is down from $105 to $80bbl. For whatever reasons, “the market” is speaking pretty loudly right now.

How low must the price of oil drop to push many frackers into bankruptcy? How long must the price of oil stay there in order to make that bankruptcy so permanent that those frackers never re-emerge and no new ones ever emerge to take their place?

If any spies for 350 are reading this comment, perhaps they could get Captain McKibben of the 350 Mothership to think about organizing and inspiring a multimillion-person effort to curtail gas use/ driving/etc. for long enough to keep the price of oil plunging and plunging? For long enough to shut down the frackoil and dis-incentivise the Keystone XL Connector and etc.? Then when the frackoil was shut down for good and for real, the Saudis could raise the price of their oil to a hundred or a thousand or whatever a barrel. That would make the carbon-skydumping reductions permanent.

My small property is in the Marcellus shale area of PA. If gas runs out by 2040, I don’t care; I’ll be long dead. But if it peters out in three years, I and all my neighbors are screwed. This is a depressed rural area and money from gas drilling is the only thing allowing us to pay our bills.

Yes, in an extractive economy people get preyed on. Mill out, landfill in up here. Same logic.

There may be some other factors at work here.

In 1998, when we had a rapid rise in the price of oil, a lot of old oil wells located in the Mid West around Kansas and Oklahoma suddenly became profitable to run again. There was a mad rush to restore existing wells and to build new pumps to open up old capped wells. It was the oil recovery that a lot of locals were praying for sense the 70s when these wells were shut down because of economic factors.

The problem was that the oil while shallow was very thick and full of impurities. It took more energy to extract the oil than could be liberated by converting that oil to diesel, the prime fuel used by these pumps.

But as oil prices rose faster than diesel, they could still turn a profit. That is until the price of diesel caught up.

The rushed to congress, warning of a fuel crises. Once these oil wells shut down, there would be a shortage of diesel. But when the market finally collapsed, there actually was a surplus of diesel, because the local market consumed more diesel fuel than it produced. And inefficient economy that became an energy sink.

I wonder is the same thing is happening here. I recall reading old reports that said that there wasn’t enough energy to be found in the shale to be worth recovering. This was not a question of technology, but basic psychics.

If true, this will prove to be an ugly truth for the apologists currently trying to save the revolution. They have been non-stop arguing that the price drop was temporary. Thus as operations shut down and begin producing less, this should cause prices to stabilize. But it may be that as these operations shut down, it will cause demand for fuel to drop even further.

Some folks believe that if they can convince EU to stop buying Russian gas, the Russian government will collapse. Then they can get back to looting.

It is not necessary that american gas exist; only that promises exist. Better, actually, that the promises be false. The collapse of EU government will provide additional opportunities.