This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 261 donors have already invested in our efforts to shed light on the dark and seamy corners of finance. Join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via credit card, debit card, PayPal, or check. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our current target.

Yves here. Richard Vague has been kind enough to allow us to feature an extract from his recent book, The Next Economic Disaster: Why It’s Coming and How to Avoid It. I first met Richard several years ago at the Atlantic Economy Summit. If my memory serves me correctly, he was then taken with the conventional view that debt was a dampener to growth…meaning government debt. The issue of what caused our economic malaise and what to do about it troubled him enough to lead him to make his own study, and he has come to reject the neoliberal view that government debt is problem and must therefore be contained.

This view implies, as many readers have pointed out, that the great lost opportunity of the crisis was restructuring mortgage debt. That would also have allowed housing prices to reset to levels in line with consumer incomes. Vague also mentions a less-widely-commeneted on debt explosion prior to the crisis, that of business debt. One big contributor was an explosion in takeover debt for private equity transactions. Indeed, a lot of experts were concerned about a blowup due to the difficulty of refinancing these deals in the 2012-2014 time horizon. But ZIRP and QE produced enormous hunger among investors for any type of asset with non-trivial yield, so the Fed enabled the deal barons to refinance on the cheap.

By Richard Vague, currently the managing partner of Gabriel Investments and the chairman of The Governor’s Woods Foundation, a non-profit philanthropic organization. Previously, he was co-founder and CEO of an an energy company and two consumer banks

In the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis, most of the economic debate has focused on the subject of government debt—on “austerity vs. stimulus.” One side blames government debt for impeding economic growth and thus prescribes a reduction in government spending called “austerity,” while the other side calls for more government deficit spending as the necessary “stimulus” for strong economic growth.

Both sides miss a much more central point.

The primary issue is not public debt but private debt. It was the runaway growth of private debt—the total of business and household debt—coupled with a high overall level of private debt that led to the crisis of 2008. And even today, after modest deleveraging, the level of private debt remains high and impedes stronger economic growth.

Rapid private debt growth also fueled what were viewed as triumphs in their day—the Roaring Twenties, the Japanese “economic miracle” of the ’80s, and the Asian boom of the ’90s—but each of these were debt-fueled binges that brought these economies to the brink of economic ruin.

Those crises are the best known, but almost all crises in major countries have been caused by rapid private debt growth coupled with high overall levels of private debt. The reverse is true as well; almost all instances of rapid debt growth coupled with high over- all levels of private debt have led to crises.

There are two claims you can count on: Booms come from rapid loan growth. And crises come from booms.

Alan Greenspan, who was chairman of the Federal Reserve until 2006 and who presided over much of the runaway increase in mortgage loans that was central to the 2008 crisis, wrote recently in reference to this crisis that “financial bubbles occur from time to time, and usually with little or no forewarning.”

Alan Greenspan is wrong.

It was neither a “black swan event” nor a crisis in confidence. There was plenty of forewarning—in fact years’ worth. This crisis was predictable, and major financial crises of this type can be seen—and prevented—well in advance.

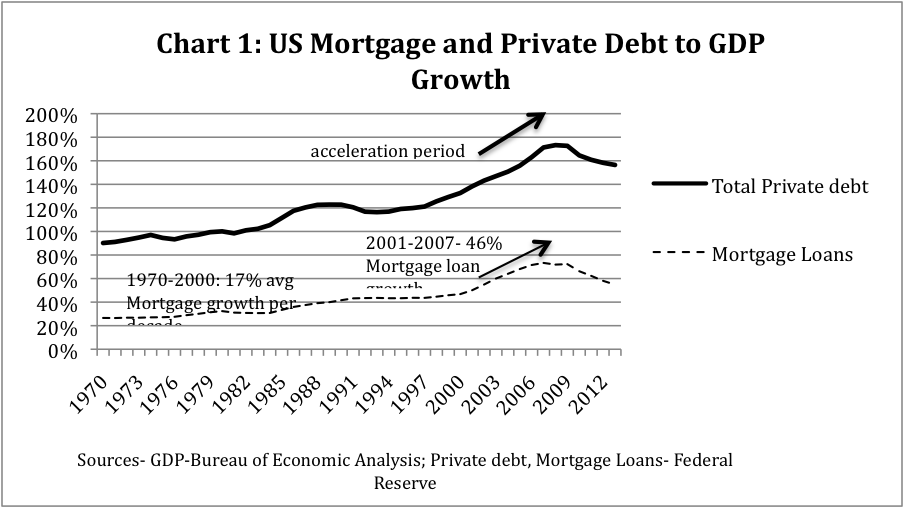

Beyond the issue of rapid short-term loan growth, the United States has been on a long-term and continual path of increasing private debt to GDP. It is astonishing what’s happened: over the past seventy years, the level of private debt to income and GDP—in the United States and across the entire globe—has climbed steeply higher. In the United States, it has almost tripled from 55 percent in 1950 to 156 percent today. What is equally astonishing is how little attention it has received.

While runaway loan growth was the cause of the crisis, loan growth at a more moderate level is a favorable driver of economic growth. This seeming paradox is one of the subjects of this book.

(Note: I use the terms economic growth and GDP growth interchangeably in this book—GDP growth is simply the sum of private, business, and government spending plus net exports. And income closely mirrors GDP, so whenever I mention GDP growth, it encompasses income growth too.)

When debt growth is too rapid, it brings economic calamity, especially if coupled with private debt levels that are already too high, since high private debt levels make businesses and consumers more vulnerable to economic distress.

For large economies, private loan to a GDP growth of roughly 18 percent or more in five years is the level at which that growth becomes excessive. (I discuss the few exceptions in the book.) On top of this, apart from any crisis, the accumulation of higher levels of private debt over decades impedes stronger growth. Money that would otherwise be spent on things such as business investment, cars, homes, and vacations is increasingly diverted to making payments on that rising level of debt— especially among middle- and lower-income groups that compose most of our population and whose spending is necessary to drive economic growth. Debt, once accumulated, constrains demand. And debt growth here and abroad over any sustained period always exceeds the income and economic growth it helps create, a troubling phenomenon intrinsic to the system.

Runaway growth in private debt (especially high mortgage loan growth)—and not growth in government debt, a lack of consumer or business confidence, or myriad other explanations—was the immediate cause of the 2008 crisis. US mortgage debt grew from $5.3 trillion in 2001 to $10.6 trillion in 2007, an astonishing doubling in six years. This contributed to high absolute levels of private debt to GDP, a level that reached 173 percent in 2008. In larger, more developed economies, when high growth in private debt is coupled with high absolute levels of private debt, it has almost always led to calamity. Since this buildup of excessive private debt occurred over several years, it should have made the prediction of the crisis and its prevention both possible and straightforward.

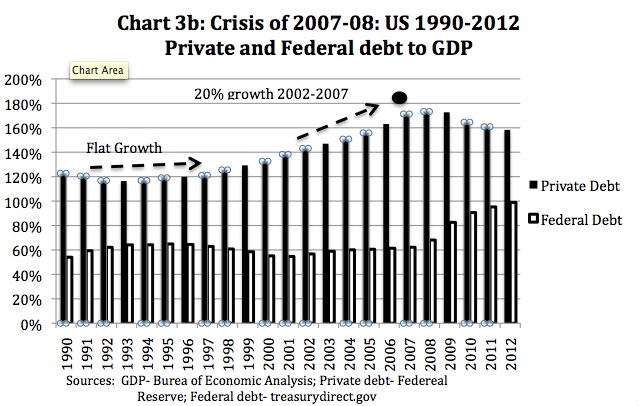

But it wasn’t just mortgage loans. Business debt to GDP picked up markedly starting in 2006, and overall private debt increased at a pace rarely seen during the last century in the United States—an increase of 20 percent to GDP in the five years leading up to the crisis. (See Chart 1.)

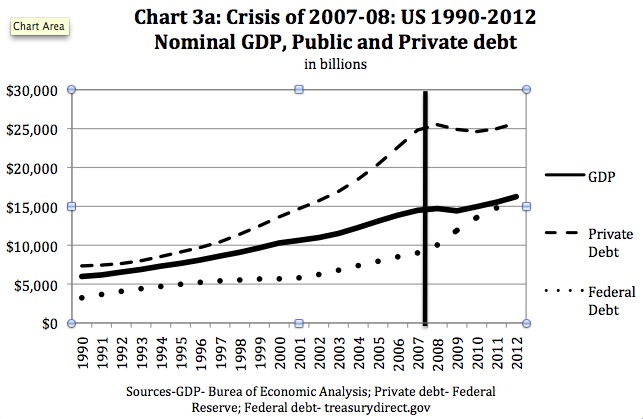

By contrast, in 2007, the federal government debt to GDP was slightly lower than it had been ten years before and didn’t accelerate until after the crisis. Benign growth in government debt is typical of the period preceding most significant financial crises.

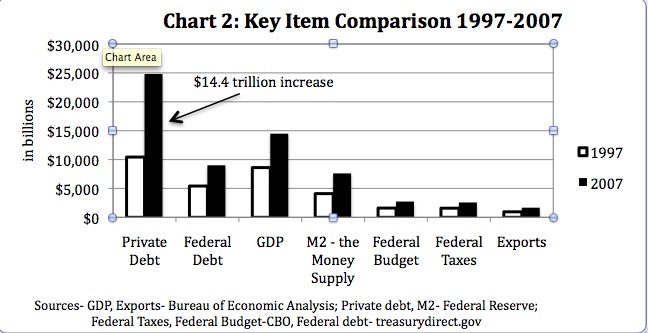

As Chart 2 shows, from the sheer dollar amounts involved, it should be no surprise that private debt would be a primary driver of the economy. This chart shows the increase in key categories from 1997 to 2007—the decade preceding the crisis:

From 1997 to 2007, lenders flooded the US economy with $14.4 trillion in net new private loans. Federal debt increased by a significantly smaller amount—$3.6 trillion—during that same period. An increase in bank loans represents the entry of additional money into the economy. For all the talk of the US government and the Federal Reserve Bank “printing money,” it is private lending that creates the most new money entering the economy. The primary constraint on that new money flooding the economy is the capital requirements imposed on those lenders. Anyone who has been granted a loan and had the proceeds of that loan deposited into his or her account has just witnessed the deposit of newly created money into the system. The idea that savings and deposit growth must precede loan growth and thus leads to loan growth is misguided. Instead, loans create money and are thus a part of what creates deposits.

For this reason, total loans are a more accurate gauge of the amount of money in an economy than the “money supply” (the sum of deposits and currency), which is in large part a by-product of that lending.

The impact of private loans in this period far exceeds the impact of any other category. For example, a 10 percent reduction in taxes for each of these ten years would have brought no more than a $2.5 trillion increase in spending by the private sector, an amount dwarfed by the $14.4 trillion in new private sector spending enabled by this increase in private loans.

While US private debt to GDP growth is currently flat, as shown in Charts 3a and 3b (which I refer to as the “debt snapshot”), the crisis of 2008 came after the point where private loans to GDP had grown 20 percent in five years and total private loans to GDP exceeded 170 percent.

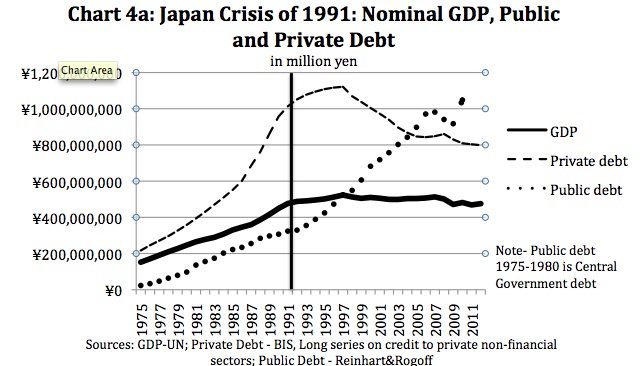

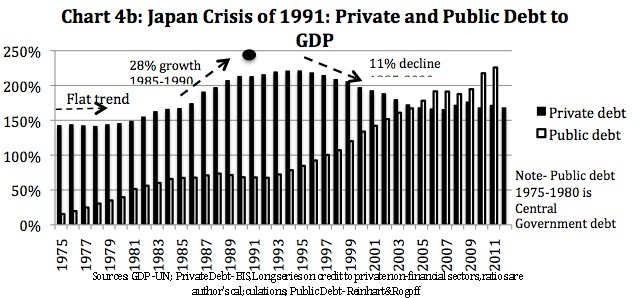

We looked at the two other largest crises of the last generation to see if private debt played a part there as well: Japan’s crisis of 1991, which followed its “economic miracle” of the 1980s; and the Asian crisis of 1997, which followed the “Asian economic miracle” of the 1990s. As shown in Charts 4a and 4b, in the period from 1985 to 1990, Japan’s private debt to GDP increased by 28 percent and reached 213 percent of GDP. And in the five-year run-up to the Asian crisis of 1997, private loans to GDP for South Korea and Indonesia grew 29 percent and 43 percent, respectively, and in South Korea, private debt to GDP reached 170 percent.

Runaway lending created the Japanese and Asian economic miracles, but those miracles brought crisis.

Government debt to GDP was relatively benign before the crash of 1929, the US crisis of 2008, and both the Asian crisis of 1997, and the Japan crisis of 1991. In the United States, even with its Middle Eastern wars and a major increase in social program expenditures, federal debt to GDP was no higher in 2007 than it had been a decade before. The five-year increases in government debt to GDP in Japan in 1991 and South Korea in 1997 were both near zero.

In fact, the government debt to GDP ratio sometimes improves in the “runaway lending” period and becomes something of a contraindicator. In Spain, before its recent crisis, government debt to GDP declined by 16 percentage points. The credit boom brings increased income to businesses and consumers, and one result is more tax revenues for the government. Most businesses and consumers feel good, even euphoric, about their financial situation during this runaway lending period. And governments start believing they have found the recipe for economic success, such that the talk is often of economic miracles. But it shouldn’t be, because the other economic shoe is now dangling and threatening to drop.

The ideal economic situation for growth in a given country and the world is to have less capacity (or supply) than demand coupled with low private debt. Instead, we have nearly the opposite situation in our time. In the first decade of the 2000s, the United States and Europe built far too much capacity, especially in housing, and incurred too much private debt. In the 1980s, Japan built far too much capacity, saddling its banks with too much private debt and too many bad loans. While all have been catching up to this capacity, none yet has less capacity than demand, and all still have high private debt. And now China, whose industrialization and urbanization long fueled global growth, has created its own overcapacity and private debt problem, building far too much capacity in many industrial and real estate projects with easy credit that fueled the most rapid buildup of private debt yet. So now the majority of the globe is in this less than desirable place. No major global economic player now has that pivotal combination of undercapacity and low private debt to fuel productive investment and help boost global growth.

Much has been written of late regarding the decline of the middle class. It is important to note that the size of the middle class grows in major countries (or the world) when there is too little capacity and low private debt (like after World War II). That is because a middle class is needed to build new capacity. Corporate debt can be used to fund the building of new capacity, while consumer debt can be used to fund the consumption of that capacity. In contrast, the size of the middle class plateaus or shrinks when there is too much capacity and too much debt (like there is at the present). Stated differently, inequality increases when there is high capacity and high debt; it decreases when capacity and debt are low.

Discussions fretting about private debt need to focus more on those debts of choice – business leverage used to saddle corporations with bad balance sheets and drive them into bankruptcy after their assets have been stripped. Too often the focus is on mortgage debt, reverse mortgage debt, student loan debt, and personal credit card debt–all of which have become massive scams operated by the financial sector. Why for example, with Fed policy as it is do we have personal credit card rates over 10%? Why can so many people paying down credit cards never get lower rates except through the shaming and yet another interest rate of “credit counseling”? And why has the CFPB so slow in cracking down on these practices on personal debt?

People who have experienced medical crises or long unemployment and after cashing out their 401(k) plans to make ends meet often max out their credit cards, at which point because they pay regularly the credit card ups their limits and they slowly go deeper in debt from crisis to crisis with the credit card company sucking out 20% interest a year, which doubles their principle in 3 to 4 years even if they are paying the minimum payment. In most cases this is systemic fraud based solely on the person’s credit score and not on payment history.

Discussions of private debt must start avoiding moral hectoring of individual personal borrowers and look as the calculated use of debt and bankruptcy by the 1% to fatten their own wealth. And yes the poster child for private debt is Mitt Romney.

When supply side economix and trickle-down became the policy in the 80s we desperately needed some way to maintain a “strong dollar” and alieviating “stagflation” – else why would we have been so stupid? But keeping the dollar strong was a fantasy because of globalization, which we also wanted. Cake and eat it too. The prescription to the dilemma should have been a short lived experiment. Instead it was allowed to go until it brought the house down. Supply side economix as it has been practiced is the exact opposite of the above recommendation to keep demand high and personal debt low. It is interesting to note that (it seems) we are moving at lightning speed to dump our reserve currency status. Good riddance. And while we are at it, lets forgive all the staggering personal debt with some umbrella bank, some sovereign mechanism, to allow private debts to be written down by 70%.

I’d say personal debt is a great thing to focus on because the decision-making trade offs that lead to debt are life experiences with which the vast majority of Americans can relate.

When wages stagnate but prices rise for the average family, it takes ever more mortgage debt, student loan debt, credit card debt, auto loan debt, etc., to simply maintain the same standard of living, never mind enjoy progress.

Some excellent points. My first credit card, back in the early 1970s, carried a 5% interest rate. At the time, mortgage interest rates were around 7%. Consequently, people used credit cards for short-term obligations and only added on to their mortgages for long-term obligations adding to the value of the home itself (i.e., new roof, deck or patio, sunroom addition, etc.). The interest rates themselves ensured that no one would borrow extra money–at a higher rate–against a home, unless the project had true long term value. It’s hardly surprising that with state legislatures approving outright usury, today’s borrowers have tried to borrow as much as they can against their homes.

Most of us here know there are any number of ways to sanely and rationally deal with the problem of excessive debt and, at the same time, not go into austerity. Obviously bringing down public debt is essential if we are interested in economic growth–now I don’t believe the elites are very interested in that but rather keeping what they already have. If we had a social democracy mechanisms could be put in place–capping interest rates, selective mortgage relief programs, government guaranteed loans to pay down consumer debt and just having a government that is not corrupt which would increase, in itself, confidence.

But none of that is possible and we will drift for some time with the status-quo. Maybe some dramatic new technology will emerge to put some life into the economy but long term you have to be bearish. At present smoke and mirrors are working fine so there is little reason to change anything.

Greenspin has been talking up gold, actually calling it “money” that is universally accepted. Whereas Bernanke said gold was not money, but an asset. If gold becomes a global standard all currencies everywhere will devalue like a stone. And that will help government, public, debt. If everyone is paying off their debt with inflated currencies then nobody can complain. Still, it would be best to not have to incur debt as a sovereign nation, but just let your money supply fluctuate ala MMT. Reinstating a gold standard sounds like protection for global private banking, which likes to have governments in debt to them. And this gold standard scheme also does nothing for national progress, it keeps it at a minimum. It also does nothing for personal debt relief. Since nobody has a job.

About your “bringing down public debt” point.

No, St Reagan proved deficits (public debt) don’t count. hahahaha – really, I kill myself.

The post says it is the private debt, its absolute size vs the economy, and its rate of growth, that matter for economic health – analogous to blood in a human, too much/too little, you got short term problems, too high/low blood pressure, you got long term problems. So we should be demanding ways to reduce the private debt from our leaders, not reduction of the public debt.

Yep, this. It is simple, a 3rd grader could understand it. The FED, notsomuch. I have been saying it for years, until “they” decide to stimulate at the personal debt level, we’re screwed. You can’t run a consumption-based economy (regardless of the merits, that’s how it is designed to operate right now) without the consumer. When privately held debt grows and grows, and outpaces private incomes for most people for decades, you eventually get to a point where the debt cannot grow anymore. When you couple that with myopic policy of turning that privately held debt into the fuel that runs your economy, you had better either change the way your economy works, or find a way to reduce the debt. Either is acceptable, but sticking your fingers in your ears and saying “lalalalalala!” or handing the people who loan-out that private debt more money will not really do anything at all.

Oh well, I guess we can all build yachts for the .01%, or something.

(Gah, cut and paste failing) This article somehow doesn’t develop the necessary focus on the relationship between debt and falling working and middle class incomes. As writers such as Wolfgang Streeck (“Buying Time: the Delayed Crisis of Democratic Capitalism”) and Colin Crouch (“Privatised Keynesianism…”) argue, in the late 60s and 70s Western business elites became militantly disaffected with the post-WW2 accord that had guaranteed a rising standard of living to those groups. They began, ultimately with great success, to offload the contribution of profits to that standard of living even as they developed financialized options to help sustain it. This offensive was carried out on a number of fronts, from attacks on unions to undermining of public welfare guarantees, etc. The result has been, first, a surge in state debt followed by a financial innovation-driven surge in private debt. Unless this is understood, analyses like Vague’s only leave us bemused over what appear to be “poor policy choices” that in fact follow a logic of struggle against the WW2 accord that has culminated in system-threatening overkill.

Debt is a feature, not a bug.

It is the mechanism by which the elite are siphoning off our aggregated wealth and monetizing our productive capacity.

Be it consumer date to extract every bit of money from the middle and lower class, to government debt to allow the government to subsidize crony bankers and military boondoggles, to corporate debt to allow companies to be put up on blocks and stripped down like a Honda Accord in Modesto CA.

While perhaps useful in specific modest does, debt has become the crowbar that is being used to raid our wealth.

Love the crowbar imagery.

Let’s say you borrow $1 million and then waste it utterly on frivolous shopping sprees and speculation in penny stocks. It’s not that you tried to lose it, it just that it somehow disappeared despite your best efforts to preserve it and grow it to $5 or $10 million.

Then the person you borrowed it from say “Oh well. Who cares? Let’s just forget about it! I don’t need it anyway.”

There’s no problem at all. Nobody even notices!

The problem only arises when they want their money back. What is it that they want? Not pieces of paper, and certainly not bits and bytes on a computer someplace. That’s where reality starts. So far, it’s only imagination all over the place — except for the shopping.

Yo craazyman;

The “Powers” are getting their big dogs ready to collect. Ya didn’t think anyone built an army the size of the Duchy of Neuie Yorke’s without just itchen to try it out? That Occupy biznez? A shake down cruise bro. Get themselves a food supply all sewn up, and the deal goes down!

‘The ideal economic situation for growth in a given country and the world is to have less capacity (or supply) than demand coupled with low private debt.’

Whut? Capacity utilization, as measured by the Federal Reserve’s G.17 series, has never reached 100 percent. But even excursions above 85 percent were associated with quickening inflation.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/series/MCUMFN

The author may be using some other definition of capacity. But even conceptually, what’s wanted is nearly full capacity utilization — with enough slack to avoid shortages — rather than overutlization, which leads to shortages, hoarding and price pops.

Got toilet paper?

The author does correctly describe the US economy as “debt-based”, rather than the conventional and sanitised term, “credit-based”, for indebtedness is what it is. When corporations hoard cash, borrow to finance enormous stock “buybacks”, outsource meaningful jobs abroad, cut R&D expenditures, all the while “down-sizing”, “right-sizing”, “rationalising labour input”, etc., etc., where’s the opportunities for expanding the domestic labour force? A “consumer” society whose consumers in the main are struggling mightily just to pay for the basics can only take on more and more debt in order to serve their function qua consumers. In fact, as should be obvious to any casual observer, debt is only a substitute for falling wages and salaries, and to the extent that gross economic maldistribution becomes the benchmark of late capitalism, consumption as a component of discretionary income has shifted well up into the top fifth quintile, and the masses are left with shopping at “dollar stores”, Wal-Mart, and the like, hardly a basis for a robust and healthy economy.

“Obviously bringing down public debt is essential if we are interested in economic growth”

Uh, no actually, it’s not. In fact, what is essential is the opposite. Public debt is what you pay private debt *with*. Public debt simply isn’t ever a problem as long as there’s unused capacity. Private debt is a huge problem.

Excellent point, and one that needs to be hammered home constantly.

It’s the anticipation of future earnings that drives credit, and ultimately supports growth, and that comes only from public investment (or mercantilism, but for us that ship has sailed).

Credit is not what drives the economy, which should be obvious by now since credit expansion has been non-existent over the past 6 years and we have still managed to grow, although at a slower rate. We’re growing at a slower rate because public spending (investment) growth is at all-time lows since WWII.

For the foreseeable future, anticipation of future earnings is not very good, and it will never be credit that leads us out of the woods.

+100

“Private debt is a huge problem.”

Here are suggestions to regulate private debt in the future:-

http://www.theguardian.com/business/economics-blog/2014/apr/15/new-policy-tool-banks-stop-asset-bubbles-economic-havoc

http://www.thomaspalley.com/?p=416

Note Paul Meli’s comment on the Mark Buchanan article and look at his graph:-

http://mikenormaneconomics.blogspot.com/2013/11/mark-buchanan-actually-economists-can.html

https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/33741/FGEXPND.png

Debt is evil, something that has been known for thousands of years.

The idea that you can bring future income forward through its purchase at a premium is an idea that feeds the ‘something for nothing’ monster that resides in each of us. And, although not exactly something for nothing, it’s about as close as you can get without stealing [of course, you are stealing from yourself].

Sooner or later, the idea that debt can actually work will need to take its place in the museum of human misery besides all of the other really good scams the best and brightest have come up with over time.

If you can bring money forward from the future, where is it now, if it’s in the future? In order to grab it and bring it forward, it has to be someplace now. And how do you bring it backward in time from the future to the past? And when you remove it from the future, what fills the hole that its removal creates?

These are deep thoughts.

These are complicated questions that can only be solved through what I’d call “harmonic analysis”, which is a complicated math thingy. Basically think of mathematical wave form functions propagating throughout a multi-dimensional space/time construct forming nodes of harmonic resonance. Those nodes are where the money is, no matter where they are in the space.

of course Craazy, since there’s no such thing as time… what a nice description.

This is to mathematical analysis what science fiction is to science. Basically I just make it up! But somehow it sounds vaguely plausible. hahahahahahah That’s the hilarious part.

“Owe a bank a quarter million dollars, and a minute feels like an hour.

Get a 0% loan from the Fed, and an hour feels like a minute.

That’s relativity.”

– Albert Einstein’s younger brother, Alan

You don’t need to be Einstein to hit the jackpot when yur funded by the Fed!

Debt is for little people.

Owe the bank a million dollars and you have a problem….

Owe the bank a billion dollars, and the bank foists the loss onto the US government…..and there is no money for infrastructure, health care, education, etc…..but there is still plenty of money for record setting bonuses at Goldman Sachs…..

Cletus, Greenspan’s inbred cousin.

This is funny but in a sick way….

Would you believe anything that comes out of the great sage known as Dan McLaughlin…even if it is banking gobbledygook

Getting to the fucking point (even if grossly wrong as below)in a brisk fashion. is not acceptable in official discourse it seems.

http://www.irisheconomy.ie/index.php/2014/10/01/a-macro-prudential-policy-framework-for-ireland/#comment-1333856

Judging by the above comment you would think Ireland is a economy closed to outside capital flows or something.

Its very simple – internal credit growth remains deeply negative in Ireland ( resident people are experiencing continued declining purchasing power and standards of life)

Meanwhile people and companies with access to external credit are pushing up the price of assets giving the illusion of scarcity.

There is no physical scarcity of houses in Ireland (even in Dublin where the system/ rental managers take a share before the remains move out of the country.)

Increasing numbers are being forced to enter the rental market.

But who exactly are they renting from ?

Houses are everywhere in Ireland.

The average family should have two at the very least

This is no less then a massive attack on ireland & previous co- op culture ( albeit it was always a rural tradition rather the the cities which have always remained in extreme poverty)

The rural tradition was of course taken over by the country and western dupes in the 1970s – with so much diesel to burn but with little brain cells to spare as they embraced the euro agri experiment which of course also was a disaster. (as it was designed to be as such)

This is such a simple yet true comment to make.

Nothing complex about it.

We are being farmed – no question about it.

Some insiders on the scheme are concerned that we get humane treatment but we are livestock in their eyes nevertheless.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VMqYYXswono

The refusal to redistribute the wealth in Ireland by simply giving away the house to mortgage holders shows us the true goal of these demonic scarcity merchants.

The simple questions were not asked back in 2009 when Rothschild moved in as the offical “advisor” to the Irish banking jurisdiction.

Such as why people don’t have the purchasing power to buy stuff when it is already made ?????

PS

Public debt is nothing of the sort in Ireland as it is in the main not held by the general public.

The extraction of domestic purchasing power by so called public debt is therefore massive.

“current rise in property prices in Dublin is not being driven by credit”

This is the most absurd comment for a economist to make.

Prices are always driven by credit.

Wealth is not , but prices sure are.

Imagine a simple closed economy model with 100 units of credit tokens / no usury and a fixed amount of goods such as Irelands current housing capital stock.

Reduce the amount of tokens to 50 units ,

It does not really matter if the population rises or falls or indeed if more or less goods are produced in totality.

The price of all goods is reduced in half regardless of population or production dynamics.

For example : The price of goods in a 50 unit economy could never be worth 60 units !!!!

Prices are always driven by credit..

Quasi-austrian nonsense at its best. Goes to show a “lefty” is a conservative in denial about it.

Some people are trapped in a time bubble from a few thousand years ago… methinks…

retail therapy

I have been looking for articles on this subject. This piece is useful in that it provides macro private debt metrics beyond which it is likely the financial system will encounter severe headwinds, and potentially worse. However, one of the counter arguments that has been presented to me and to the view expressed here is that the private debt to GDP ratio ignores the effects of very low interest rates.

Basically the argument (as I understand it and as someone who is not an economist) is that with the Fed’s massive QE-ZIRP injections of Cash into the financial system, liquidity within the financial system and ROI hurdles are now so low that deleveraging and private debt levels are no longer a significant concern. The view is that any “Minsky Moment” h/b deferred indefinitely as a result, and that the “private sector” (i.e., banks and financial markets) are perfectly capable of meeting organic growth in the real economy.

It is clear that this is not what is actually occurring, as TarheelDem has pointed out so very well in the first comment above.

I’m glad that I took the time to read this post; it’s gobsmacking.

This analysis and the stats are powerful.

Just yesterday, David Stockman put up a related analysis that you may find helpful:

http://davidstockmanscontracorner.com/the-lie-of-lehman-revisionism-a-bailout-shouldnt-have-happened-and-didnt-matter/

Debt became the greatest profit center in American life, and the person that I’ve seen provide excellent documentation about it is Sen. Elizabeth Warren in “The Two Income Trap”. Debt and inequality are inextricably linked.

The post makes a point that I hope will be widely repeated: it was private debt, not public debt, that created the problem. That requires consumer education, tighter restrictions on banking, and tossing ‘austerity’ in the policy dumpster going forward.

Here’s hoping this author considers giving a TED talk, or some other public presentations, because this analysis seems rock-solid.

Fantastic post. Thanks, Yves!

Alan Greenspan was indeed wrong and wrong about many things. Team Greenspan was largely responsible for the escalation of the debt boom and dismissed anyone wanting to do something about it as anti-market. He stymied any consumer protection.

Mr Greenspan and his predecessor deserve a heaping amount of scorn for the recent debt induced bubbles which eventually went bust. But hey, he’s a Washington insider. All is forgiven and forgotten.

GDP: Blaming Outcomes, Expecting Change, & Producing Noise

The only person you can change is yourself, with substantial effective work. Whether others follow the example is up to them. That is the paradox of free will, an investment in adaptation upon which culture depends.

Civil law, creating the illusion of stability by blaming and punishing the outcome, only to re-enforce it, is pretty d* stupid if you think about it. Economies create distributions of outcomes, recognized or not, including the homeless, bankers and Charles Manson.

Before the politically free speech, equal rights to slavery, bait and swap maroons showed up at university, getting in was easy, but staying required work. Now, getting in is harder than going to prison and you are guaranteed to graduate, with a degree in arbitrary mythology. And printing money to export the lost purchasing power, which can only come back multiplied, isn’t helping.

One day President Obama is receiving the Nobel Peace Prize and the next he is bombing the world, blaming Putin for doing much less next door, after placing a nuclear deterrent on his doorstep, to protect Saudi extortion, and Putin announces more oil, shocking. You have to practice some discretion when/where you apply your talent and skills, and patriotism is not a reliable condition.

There is nothing wrong with converting AC to DC as a means of control, but you have to realize that you are creating a closed system subject to increasing external pressure, producing decreasing internal volume, in a positive feedback loop. Without reconversion in an increasing number of ways you are going to get intermittent failure and then distribution of failure and then collapse. That’s why you are seeing falling elevators, disappearing planes and derailing trains, with critters blaming each other and planning another round.

Measuring convenience instead of adaptation as productivity creates dumber, slower and lazier; arbitrary, capricious and malicious; ignorant, jealous and greedy slaves to the stupidity, running around in circles in an imploding economy. You can have plumbing and electricity, but creating artificial complexity to replace natural input is a recipe for disaster. The point is to move forward, not to replace brain function with artificial intelligence and automation.

You have to identify and make the gate for economic mobility to exist. Apes arbitrarily issuing objectives, hoping the monkeys will accidently find a gate, to build best business practice is a problemsolution. The majority always seeks security in numbers, assuming incorrectly that the last majority had a clue, which simply reshuffles the deck, always ending in a losing hand of solitaire.

If you are diligent in qualitative analysis, quantitative analysis is rarely required. The empire runs exactly backward. When you first run a backhoe, you have to measure the ditch, and lose sight of what is going on around you, increasing the probability of disaster. Pretty soon you start measuring the depth with the bucket/crow, watching and expecting what is coming next. Training apprentices is an investment, required for NPV.

Sometimes a homeless person or a professor or an elevator mechanic is just that, and sometimes not. Don’t take the public, private and non-profit corporations too seriously, except to develop your building block skills, for when/where you will need them. If you chase a corporate job with corporate skills, the empire, which has its uses, collapses on itself.

Without labor that capital stock would not exist, and there would be no beginning and no end to the circuit. That double-sided mirror is a fuse of fuses, which allows you to work on the system. Because a previous culture chose to build a bigger, dumber SMART technology, doesn’t mean that you have to follow it blindly along.

Whether you choose to explore the atom or the universe, life is life, wherever you go; it requires work, as measured beyond your horizon. That’s the feedback loop you are seeking. Just make your gate, and the nonsense will take care of itself, behind you in time. Speed is a function of direction, not the other way around.

An economy begins and ends with labor.

The Surprisingly Intelligent Viking series deals with the effects of Norse inflation (as a result of gold hoardes shipped into the local economy via plunder)

Where brother fights brother .for dimishing local resources.

The wise chieftan Ragner realizes that gold or money is merely a mehanism and not wealth.

But he uses the gold to buy the Shamen / priests judgement so as to unite the tribe by forgiving his brother and thus they are free to seek real wealth (land) abroad.

So off to the British Isles they went…..

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Yt6Kiw2s3L0

Of course no more new land awaits beyond the horizon but the old land of western europe is no longer intensively farmed – its more of a extensive petro based agri enterprise of export / value added crap rather then food for home consumption.

Given the extensive house development in western Ireland asa result of the credit explosion there is a capacity to service each house with perhaps 10 to 20 acres ~ of albeit marginal land in many cases which could service domestic demand if there was a return to domestic purchasing power via the introduction of a social credit scheme.

However current agriculture (this goes back a long long time) now involves the rotatation of cattle between the west and east coast before subsequent export to the teeming populations of London and other fleshpots.

For example ; current animal breeds are not suitable for home consumption as they require huge inputs.

Trade is structured & orbits around the the centers of interest bearing money rather then where the resources are local.

At present there is no way a 20 acre farm is viable as the local purchasing power is simply not present and for no other reason really.

I preformed a experiment myself over the summer.

I caught many 1000s of fish from a plastic boat I have and merely gave the stuff away.

There is a huge bounty out there (despite Industrial scale fishing beyond the horizon) but the local money is simply not present.

The money comes in via tourists flying into Dublin & renting a new car – .by the time they get to the local economy they have enough tokens to buy a Ice cream or something.

The pubs are empty because the local labouring men have no real jobs.

“Both sides miss a much more central point.”

I think the most significant aspect of the austerity vs. stimulus debate is that it is substantively irrelevant for the big picture questions of political economy. Instead, it is a key character in the kabuki theater, the purposeful obfuscation of what is actually happening. Namely, of course, that we are in the midst of an ongoing crime spree. Private debt increases are one of the more easily quantifiable metrics by which to measure the looting.

Neither side misses that central point. Obfuscation is exactly the point, to debate trivialities in a polarizing, tribalistic fashion so that there is less space for exploring reality and cooperating with Others. What I find intriguing is why so many leftist intellectuals participate in the fraud, preaching that net deficit spending is good regardless of how the money is spent.

The austerity vs. stimulus framework reminds me of this fun tidbit from a few presidential cycles ago. As if it matters whether the NSA’s computer systems are Macs or PCs.

http://www.boston.com/news/nation/articles/2003/11/11/cnn_planted_question_at_debate_student_says/

Indeed.

If more deficit spending gets funneled to the military or to our obscene healthcare rent-extraction contraption, I’m really not interested.

It’s not inflation if your hospital bill goes up. It’s growth!

This article is very illuminating. I wonder why the media is so focused on public debt, and is relatively wordless and speechless when it comes to private debt.

The positive about private debt, is that, supposedly, it is backed by capital 100% that can be converted into dollars.

Public debt is backed by the goodwill of the U.S., the faith and confidence of the people, which is a much more abstract, and thgus risky form of debt than debt backed by specific collateral.

Don Levit

Public debt is everybody and hence nobody’s real responsibility. Private debt is considered to be the individual’s real responsibility. But if one starts to deeply talk about that responsibility, one needs to ask who is really involved. Turns out there are two parties! The one who got the money, and the one who lent the money. And someone may ask: “What responsibility does the one who lent the money has?”, and you don’t want to answer that question. And if you look even deeper at the “who’s involved” questions, you see class and culture issues coming into view (rather than just the financial issues of who-owes-who-how-much. And the class and culture issues are the real powerful questions here and you really don’t want to answer those questions, do you?

From proposed MMT Textbook Mitchell and Wray:-

“In the historical past, the Treasury would spend directly through the issue of money – denominated IOUs, whether these were tally sticks, metallic coins, or paper money.”

http://e1.newcastle.edu.au/mmt/chapters/Chapter_9_draft.pdf

It would seem reasonable to suppose that the abuse of money creation by monarchs to fight wars of aggression with other countries gave the Fat Cats of those times the opportunity to extract rent under the guise of a public good in making state money creation subject to deficit financing.

I agree with the author that private debt increases usually lead to booms, but the increases only result in crises when basic principles of lending are tossed out the window. When we bought a home back in the mid-80s, the standard equity contribution was 20%–anything less and you had to purchase private mortgage insurance for the balance. You also had your income and budget thoroughly scrutinized to ensure that you could afford the mortgage and real estate taxes. Had those guidelines been maintained, even with substandard loan servicing, an increase in mortgages wouldn’t necessarily have led to a crisis.

On the business side, as Tarheel Dem says above, the typical leveraged buyout today strips out assets, or overpays lenders, making it inevitable that the purchased operation will not be able to service the debt. Back in my banking days, in the late 1970s, my large financial institution actually received a call from D.C. asking the bank to temporarily suspend all “non-productive” lending–in other words, M&A loans–and we voluntarily put the brakes on.

Point being that the Feds could do a lot more to ensure that increased private debt doesn’t become a runaway train. Booms only lead to crises when spending is unregulated.