In case you managed to miss it, there’s been a fair bit of hand-wringing over the fact that Japan has fallen back into a recession despite the supposedly heroic intervention called Abenomics, whose central feature was QE on steroids.

But Japan of all places should know that relying on the wealth effect to spur growth has always bombed in the long term. They were the first to try that approach of a large scale. That idea was the basis for the Bank of Japan keeping monetary policy super loose in the later 1980s. They explicitly wanted to increase stock market and real estate prices to stimulate more consumer spending. We know how that movie ended.

As Marshall Auerback, who in a previous incarnation was an analyst of the Japanese economy, pointed out by e-mail:

Japan has fallen back into recession because the government has repeated the mistake of 1996 by hiking the consumption tax.

Now Abe says he’s not going to increase it again.

Given that QE has never “worked” anywhere I never could understand why Japan’s version should work now.

Wolf Richter provides more granular detail:

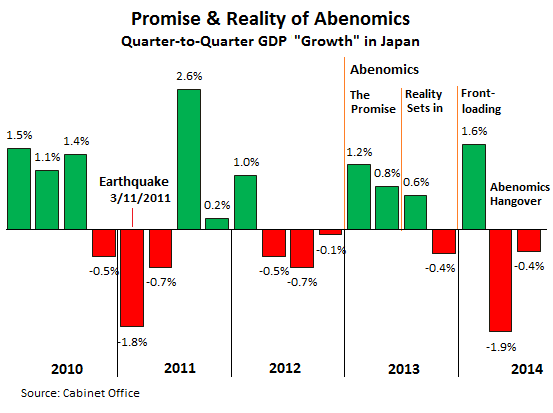

Here is what this fiasco of Abenomics looks like, annotated:

The chart shows how the hype of Abenomics initially created a lot of excitement. Then reality set in. This was followed by the brief but thrilling era before the consumption tax hike that triggered a vast bout of front-loading, much like the prior consumption tax hike 17 years ago had triggered. This was not a surprise, not to readers of WOLF STREET. But Abenomics apologists were claiming at the time that Abenomics was performing miracles.

Then the hangover set in as the tax hike took effect on April 1. The prior tax hike had been followed by a steep and long recession. This one appears to follow the same procedure. Again, no surprise.

In fairness, Abenomics did include a burst of fiscal spending, but a short-term jolt followed by a tax increase was not going to work.

But the more interesting question is why anyone is surprised at Abenomics’ failure. Chalk it up again to fealty to orthodox, as in bad, economic thinking. Bill Black has a field day with a New York Times story that attempt to rationalize what happened:

The New York Times published a story by Liz Alderman dated November 17, 2014 entitled “As Japan Falls Into Recession, Europe Looks to Avoid It.” The article begins with a burst of (unattributed) economic illiteracy.

“Japan looked like the model for economic revival. Growth was back on track. The stock market was surging. Inflation, which had eluded Japan for decades, was even returning.

But Japan’s grand economic experiment, a combination of fiscal discipline and monetary stimulus, is collapsing. On Monday, the country unexpectedly fell into recession, a downturn that has painful implications for the rest of the world.

Japan’s unorthodox strategy was supposed to offer a road map for other troubled economies, notably Europe. Fiscal belt-tightening and tax increases, while leaning on the central bank to pump money into the economy, was expected to help overcome a malaise.”

In a prior column I gave mock praise to Alderman because after editorializing for eurozone austerity for years in her columns she finally admitted that “many economists” criticized those policies. I cautioned, however, that the NYT reporters, including Alderman, assigned to cover the eurozone “are austerians to the core.” Here comments about Europe and Japan prove my point. First, Japan did not look like “the model for economic revival” when it endorsed austerity through sharp increases in its sales tax. It looked like a model for a gratuitous recession. The stock market surge and moving towards achieving desirable levels of modest inflation occurred in part in response to the fiscal stimulus that the new Japanese government decided to replace with fiscal austerity. But other government policies were more important in explaining these results – and explaining why they were artificial. By announcing the rise in the sales tax from five to eight percent in advance the government spurred a sharp increase in consumption of durable goods prior to the increase. By moving government funds from safer investments to stock purchases the government spurred a rise in the stock market.

Japan did not fall “unexpectedly” into recession from the perspective of financially literate economists. It fell into a recession that it was warned was a grave risk given its adoption of austerity through a sharp increase in the sales tax (with a further increase scheduled for next October that will likely now be suspended). Contrary to what Alderman’s column implies, Japan has not even reached its inflation target of two percent. Austerity was madness in these circumstances. We certainly never expected it to work in Japan.

“‘The numbers are absolutely awful, beyond-description awful,’ said Peter Tasker, a longtime analyst of Japan’s economy and a supporter of Abe’s policies. ‘It’s clear that the tax hikers and the fiscal hawks have tanked the economy.’”

Alderman is shocked, shocked that austerity has (again) caused a gratuitous recession. There is an ironic proof of how non-shocking Japan’s latest recession is – from two-and-a-half years ago. It is ironic because it is contained in an economically illiterate article in Bloomberg of the usual “there is no alternative” (TINA) to austerity dogma. Every aspect of Bloomberg article is driven by ignoring the fact that Japan has a sovereign currency and inadequate inflation (and, often, deflation). The article’s meme is that Japan’s government is dealing with its acute “fiscal crisis” (sic) by showing the courage to “tackle [the] sales tax ‘taboo’ that Obama won’t touch.” As bad as the Bloomberg article was, it did admit that raising the sales tax would endanger Japan’s “economic growth” and that “the last time Japan did so, it helped cause a recession.”

The article (unintentionally) admitted that Japan’s “fiscal crisis” was fictional because Japan has a sovereign currency.

“Japan’s debt to GDP ratio is estimated to rise to twice the size of the economy this year, compared with Greece’s 123 percent, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

A deteriorating fiscal situation hasn’t spurred an increase in Japan’s benchmark bond yields yet, with 10-year securities yielding 1.3 percent — the lowest among G-7 nations because of the economy’s deflation.”

The supposed “crisis” from a budget deficit is supposed to be hyperinflation. Japan, according to the article was suffering from “deflation.” Some “fiscal crisis!” Hyperinflation is supposed to cause crushing interest rates when the government borrows money – except that Japan was able to borrow enormous sums as exceptionally low interest rates. Some “fiscal crisis!”

To sum it up, Bloomberg praised Japan’s leadership (Abe’s predecessor) for taking an action sure to reduce economic growth and that had recently thrown Japan back into a gratuitous recession, in order to “fix” a fictional “fiscal crisis” that was actually critical to recovery. The article then turned to demeaning Obama as lacking the courage to inflict a consumption tax (VAT) on the U.S. despite (sound the hysteria horn) “a projected record budget deficit of $1.6 trillion this year.”

Yves again. So understand full well why austerity gets such favorable treatment. In its current version, where central banks use QE and super-low interest rates to offset its bad effects, the result is rip-roaring asset prices and a continued shift of income and wealth to the rich. The financial classes, who have considerably sway with the media, want to be sure these beatings continue until morale improves.

The sales tax own-goal notwithstanding, I’ve also read that Japan Inc. has been shipping production overseas over the years so the devaluation hasn’t boosted exports as much as thought. One of the vehicle companies CEOs(either Nissan or Honda I think) said the devaluation was irrelevant and they would not boost production in Japan. Their balance sheets have never looked better, though, record profits all around. Anyway why does everyone think they can net-export their way to success? Who’s supposed to be run all the gigantic trade deficits?

Where did Abe’s economic advisers get their educations? The policies they’ve been flogging for the last two years look like they were taken right out of a monetarist 101 textbook, even going all in on Quantity Theory of Money which is itself a huge empirical dud.

Yves did post something from me a couple of days back where I attempted to explain why this might be (in a context of the TPP, but the underlying motivation is the same). While it probably got completely lost as we merrily wandered off topic and onto events surrounding WWII, I did make the point that the Japanese do pretty systematically seek to gather inputs from what they perceive (sometimes rightly, sometimes wrongly) as sources of expertise.

Up until very recently, one of the best sources was deemed to be the U.S. (yes, and stop laughing you at the back of the class). I’ve got a (Japanese language) text book, circa 1995 vintage, which waffles on about what Japan really needs is a good dose of deregulation, a more open internal market, more flexibility in the labour force, an end to job-for-life employment security and more focus on shareholder value. Honestly, it reads like some neoliberal drinking game, it really does cover all the bases. There are extensive quotes from Greenspan and Buffett. It cites all the usual-suspect economic theories and says, basically, Japan needs to get with the programme like all the other “successful” economies such as the U.S. do.

In Japan, as elsewhere, there’s preciously little in the way of alternatives given widespread prominence. If anything, it’s more conservative on that score than the U.S. or Europe.

So I wasn’t at all surprised to see a bit of doubling down through “Abenomics”.

You must inform the Japanese, immediately, the U.S. isn’t all that.

“what Japan really needs is a good dose of deregulation, a more open internal market, more flexibility in the labour force, an end to job-for-life employment security and more focus on shareholder value.” via Clive

So let’s redistribute the common stock of all corporations EQUALLY with their citizens and then we shall have greater equity via equity and greater sharing via shares.

Let’s stop ignoring an obvious solution to inequality without harming the economy.

Russia did that during the breakup of the Soviet Union with it’s huge privatization push. All citizens got the same number of shares. Within a year or two they’d all been relieved of them by what is now the Russian Oligarchy, with the help and advice of Jeffrey Sachs and the Harvard boys.

A better deal might be to make them non-transferable, and hand out enough to provide a basic income on the interest. Kill 2 birds with 1 stone, so to speak.

Poland did this too. Left leanig econ commentators speak of this as a heist of the century. Incidentally the prime minister that was responsible for this policy just got elected to the euro parliament for the second term.

A better deal might be to make them non-transferable, and hand out enough to provide a basic income on the interest. Kill 2 birds with 1 stone, so to speak. zapster

That has a Biblical precedent of sorts with the non-transferable agricultural land of the Old Testament (see Leviticus 25).

Anyway, it’s obvious that assets have been legally stolen via a government-subsidized credit cartel so it’s obvious that they should be redistributed.

Japan and Europe consistently fail to understand that America has fantastic amounts of accumulated capital and natural resources, so when America makes a dumb bet on a stupid theory, a lot of middling and poor people get hurt but the nation itself stays very rich and powerful because it is going to take some time to eat through that seed corn. Japan and Europe have no such buffer against stupidity, but they emulate the Americans nonetheless. American wealth and power seems to blind everyone to the vicious and stupid nature of much of our internal arrangements (millions in poverty, millions in prison, tens of millions living hand to mouth or on credit). Foreigners see the successes strolling around London, Paris, and Kyoto buying up stuff and acting like Masters of the Universe. They miss the hollowing out of this Republic and the squandering of our collective birthright. The worst are my beloved British. Their leaders from Thatcher on hate their own country and want to destroy it in order to emulate American “success.” They have all been de facto traitors. Abe seems to be equally mesmerized.

Very true, Thatcher was enamoured with the U.S. and tried to emulate what was thought to be the factors which made America great. Unfortunately, she picked up on what Reagan thought made America great. Which wasn’t the truth, he missed the specific causes of the “golden era” between c. 1950 and 1975-ish and instead attributed it to what we’d now call financialisation… They both saw when they wanted to see.

Likely some big league university in USA, like every economist that get into these positions…

The headline “Why is Anyone Surprised?”, well just because every economist, almost every pundit, and every central bank is in the thrall of the utterly failed policies behind this and are true believers. Scathing they are towards anyone who dares challenge the wisdom that rising prices and the suppression of savings are somehow good for us. The current monetary & economic systems today are not working for 90% of the population; I guess we’ll just wait until it’s 95%, or 99%, or 99.999% before anything changes. As with Obomba we must decide whether they pursue these policies because they are stupid or because they are evil. I’ve settled on a 50:50 blend as the answer. I wish however we had “just stupid”, or “just evil” as it might be easier for regular people to recognize.

captured and corrupt; million times worse than a whore

thus

stupid and evil and bought

This policy was pioneered by Takahashi Korekiyo in the 1930’s. It was somewhat of a success and reduced the impact of the Great Depression on Japan. Unfortunately, in the end he was assassinated by military officers because he reduced military spending. I also believe Japan started experiencing hyperinflation in the end – not quite sure about that but it is my recollection.

In fact our own Ben Bernanke has wanted to follow Takahashi’s model.

Unfortunately, the model is not suitable for current economies which started in far more debt than Japan had in the 1930’s.

Takahashi’s fiscal and monetary policies during the Great Depression were in many ways similar to what Keynes later published just a few years later in 1936 in The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. It is thought but not proven that Takahashi’s success contributed heavily to Keynes’ theories.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takahashi_Korekiyo

To answer your last question, the United States.

Surprised? I filed this under “shit, no” back when this lead balloon was first floated.

Pardon me for repeating my post of August 13, 2014 at 3:08 pm, but it’s still apropo:

Mina-san wa [folks], we have been through this twice before. Japanese PM Noboru Takeshita first won enactment of a 3% consumption tax in 1989. He resigned the premiership shortly thereafter as his poll ratings fell into single digits. Within months the immense Nikkei bubble popped, bringing both stocks and land prices crashing down by 80%.

In April 1997 under PM Ryutaro Hashimoto consumption tax was hiked to 5%. Promptly the Japanese economy fell into recession.

Now the fools hiked it to 8%, and GDP got smacked again, as any idiot could have foreseen. One down quarter don’t make an official recession, but the chances are pretty good that it will become one.

Japanese say that people over 50 can’t learn anything. But in the case of Japanese politicians, they are ineducable at any age.

Politicians everywhere get it. Austerity and flat tax increases require monetary stimulus for risky asset inflation and wealth effect transfer. Europe has implemented the first part of the equation in order to destroy the most progressive economic systems in the world. They may never make it beyond faux monetary stimulus, but the fact they are trying to do it despite structural and legal barriers and it’s working to drive asset prices higher shows how committed the elite are to the process.

The markets are now the only measure of success and are conclusive proof that it’s working as designed for the few and not the many.

Your final para is spot-on.

Austerity – starving the horse that pulls the economy – is having predictable effects.

You remind me of this:

Deuteronomy 25:4

It’s simple:

1. Contrary to popular belief, and what central banks claim, (Click) QE does not add any money to an economy. In fact, by reducing the amount of government interest paid into the economy, QE subtracts money from an economy. So QE is recessive.

2. Taxes subtract money from an economy. So, taxes are recessive.

3. A (Click) Monetarily Sovereign (See) government never can run short of its own sovereign currency, so never needs to tax and never needs to borrow. But if it does foolishly borrow, the (Click) GDP/debt ratio is meaningless.

4. Japan’s (and America’s) austerity is not the result of ignorance. It is intentional, to (Click) widen the gap between the rich and the rest.

See? Simple.

Rodger Malcolm Mitchell

All the effort to keep the system going is very Brazil. When Japan discards neoliberalism we will know it’s over. Our Treasury and its agent, the Fed, are incapable of repairing a terminal global monetary system, which we put together to maintain capitalism at all costs. This global system was actually a weapon of the cold war – it wasn’t really even a monetary system at all unless a system of bribes is a monetary system. But we’ll be the last to confess it is hopeless. I wonder if it is pride more than anything – the embarrassment over all our aggressive hubris. Japan can not export its way out of a cardboard box these days. Nor can we. Trade itself is a form of foreign relations in lieu of war. The alternative to the “system” is sovereign money. But that implies sovereignty – so can’t have that. Even tho’ we have completely lost control. Hearing the Fed spew on about inequality is getting old fast. And all those hysterics about the great crash coming that will destroy all currencies, etc. That stuff is a red herring. The worst has happened. And now we seem to need a clean-up of the clean-up because all our efforts have made things worse. If the most we can hope for is stability via QE in some form and QE is based on borrowing via bonds but it simultaneously destroys the underlying economy – well it’s just Karma. How long can we hold on? Let us all just admit how absurd it is to continue this way. Discard the old system, and give everyone an equal stake in the future. And while we are at it we need to acknowledge it will be a future of very limited and sustainable growth. Sorry about this rant.

Love a good rant.

Re: neoliberalism

What’s to discard when nobody is sure what the word means? Does “discarding neo-liberalism” mean they they going to “discard” authoritarian top-down government? Really, in Japan? Are the “nice people” going to come in and run things? (Do these nice people have a name for their new non-neo style of government; I sure hope it doesn’t include the word neo in it). Will the “bad neo-liberals” all move to another country? Hope they don’t move, here we have enough “bad people” already.

You do the best rants in the business.

American has austerity? How much spending is required to qualify for non-austerity? Assuming we all agree that the US government is hopelessly corrupt how is “good spending” to come from a corrupt government? Or, does it matter if there’s “good spending” as long as there’s spending? So more wars (good, because it reduced austerity). More freeways (good, it reduces austerity). More airports (good, it reduced austerity). More green-growth (good because it has the word green AND growth and reduces austerity).

What?

“how is “good spending” to come from a corrupt government?”

Well, I would say if I’m starving, food stamps would be “good spending.” Is this a problem?

Roger: Well said.

QE can have an effect via expectations. It’s not clear how this works (or should work), but I recall Krugman saying that we should make the public believe that rates will stay low for a long time so that they develop inflation expectations which should eventually materialize into actual inflation. Or something like that, who knows.

“Japan looked like the model for economic revival. Growth was back on track. The stock market was surging. Inflation, which had eluded Japan for decades, was even returning.”

I love it how “a stock market surge” and “the return of inflation” have become the telltale signs for economic revival.

Most of the population owns hardly any equity and even fewer make money from increasing inflation.

This seems to represent a ‘victory’ of the Bank of Japan (monetary) over the Ministry of Finance (fiscal) with its public bank the Post Bank. Well run, these public banks can supply low interest loans to corporations and government entities for programs in the public interest. Instead as mentioned with QE we ger a false appreciation of asset prices.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-11-17/abe-s-1-trillion-gift-to-stock-market-shields-recession-gloom.html

““It’s binary — you either believe in the market or you don’t,” said Luschini, who helps oversee $67 billion including Japanese stocks. “We aren’t taking a secular view that the Japanese market looks great because the economy looks great. We view this as tactical. If investors do warm to the fact that market could respond favorably to these positives, that’s a tactical reason to own it.”’

This article confirms the fact that the “print and spend” contemporary Keynesians are more akin to religious zealots than to economic prognosticators. No amount of evidence will change your deranged belief system. Collapsing real incomes of the entire Japanese middle class … no problem! Thirty-five percent plus decline in the value of the nation’s currency over two years … why worry? It is all the fault of “austerity”, a term which when associated with Japan, a nation running colossal budget deficits and with unparalleled accumulated debt, should bring howls of laughter from anyone with four connected brain cells.

And this throwaway line is actually the money shot of the piece … “In fairness, Abenomics did include a burst of fiscal spending”. It should have been followed by “Of epic proportions, a Keynesian delusionary experiment conducted on 120 million hapless citizens, bankrupting the nation with worthless public malinvestments, though enriching numerous politically-connected crony contractors while impoverishing the masses.”

Those deficits should have just been “printed”, not borrowed (if they were), and distributed equally to the Japanese population with sharp limits on new credit creation by the banks to preclude a new bubble.

Japan returns to 1997 – idiocy rules!

Posted on Tuesday, November 18, 2014 by bill

http://bilbo.economicoutlook.net/blog/?p=29506

The government started withdrawing its fiscal stimulus too early – even though growth in government consumption continued through 2010 as public investment started to contract. While the non-government components of spending were starting to recover they were not strong enough to resist the slowing fiscal impact and so real GDP growth started to moderate.

The fiscal response in the most recent crisis has been strong and even though net exports once again started to drain growth the overall slump instigated by this devastating natural disaster was relatively modest and short-lived. Once again the recovery has been led by a strong counter-cyclical fiscal response which has also boosted private consumption growth.

But with the IMF and OECD all hectoring Japan to reduce its deficit the growth in public consumption and investment spending has declined dramatically and that is reinforcing the effects of the sales tax and related austerity measures on private spending.

…

please check also the graphs that accompany the article for some perspective

Ahem, you don’t get it. Abenomics was not “print and spend”. It was extreme monetary measures that goose asset values. The government didn’t spend, save a jolt at the beginning that they then undid with consumption tax increases. This was most assuredly not Keynesian. And QE is not money printing, it’s an asset swap (securities for cash).

As I stated before, deranged and delusional. Japanese budget deficits the past five years as a percent of GDP: 2014 -7.6%, 2013 -9.2%, 2012 -9.0%, 2011 -8.7%, 2010 -8.3%. If this is your definition of austerity, there is no basis for a rational discussion. And calling quantitative easing an “asset swap” rather than money creation, when the yen did not exist before the “swap” … well, you might as well call QE a rhinoceros, as it’s just as sensical. The collapsing value of the yen in terms of just about anything on this earth might offer you a clue as to the validity of your belief system!

US spending during World War II produced deficits of 10% to 20% of GDP. Economist agree that it was World War II spending that finally pulled the US out of the Depression. However, the US also had its bad debts wiped out (through bankruptcies) or restructurings (like the HOLC) during the Great Depression. Japan has not cleaned up its banking system. That is a big reason why its other efforts to get its economy out of the ditch have failed.

What you seem incapable of understanding is:

1. Taxes do not fund government spending for a fiat currency issuer. They drain savings. Japan is already saving too much. That is why the government is trying to do QE. It wants the public to spend more, via generating a wealth effect.

2. Since taxes do not fund spending, the only risk of too much spending in a fiat currency issuer is generating too much inflation. Japan desperately wants inflation.

3. Not running big enough deficits when the public (consumers + businesses) don’t spend enough is what lead debt to GDP ratio to rise. The IMF has basically admitted it. Government spending increases GDP MORE than the amount spent. It’s called a fiscal multiplier. So when you run a deficit, even though the absolute amount of debt increases, it falls on a percentage basis, since the GDP grows even more. And remember that governments don’t have to issue debt. They can just deficit spend. The debt is for the convenience of savers who want a secure asset

4. Re depreciating the currency: exporters desperately want cheaper currencies. Many observers think that the real reason Japan is doing QE is as a deliberate competitive devaluation, since it is clear that it does not stimulate spending. The Japan was below 120 to the dollar in the 2000s and Japan did just fine.

As for the last part of your rant, it’s you who are clearly operating out of a belief system and it appears to be that people should suffer out of fealty to bad economic ideas.

It is amazing that two people who graduated from the same undergraduate university class, who took the same economics courses from the same Keynesian professors, who both went on to prestigious business schools, and who both worked entire careers for the largest financial firms in the U.S, could have such wildly different views of the financial world, and what is sane fiscal and monetary policy. At what point will you realize the errors of printing base money relentlessly? Yen down 50%? Down 75%? Down 99%?

Yves, there are a couple of things I’d like you to clarify in your good argument.

You say that “the only risk of too much spending in a fiat currency issuer is generating too much inflation.” But isn’t making lousy investments with a relatively low multiplier effect also a risk? I ask this as somebody who pays Japanese taxes and is fed up financing “bridges to nowhere,” a practice continues in spite of “austerity.”

Not only financing useless budgetary items but also continuing to pay for the “service” on the debt incurred. This brings up a question about MMT theory. Isn’t there a downside to having a huge internal debt financed by government bonds whose interest rates may rise considerably? Isn’t it desirable to pay off all or part of the internal debt when the economy is doing well?

Yes, there is “a downside to having a huge internal debt financed by government bonds”! It’s called a situation where no free market player wants them, neither foreigners nor your own citizens, your central bank feels forced to monetize greater and greater amounts of them, and your currency collapses … sorta like what’s happening in Japan right now!

It is impossible for U.S. government securities not to be purchased at whatever interest rate that government prefers. The auctions cannot fail.

Ben, Supposing that the US govt can sell securities at whatever interest rate it pleases, can the Japanese govt also do so? And if it can now, will it be able to continue to do so as investor attitudes change? There’s anxiety here in Tokyo about the prospect of the government having to raise interest rates at some point in order to attract buyers and ending up in difficult fiscal straits for that reason. Will the Japanese govt or Nichigin always be able to set its bond rate, and if it can’t does it matter?

Yes, if it wants to.

Japan has a monetarily sovereign currency with a floating exchange rate. It can do what it wants. The consequences are the issue, and the subject of economists who understand how it works.

Adding to MRW’s comment, Japan’s monetary system structure is identical to our own. They have banks called primary dealers, required to by government securities and create a market. The Bank of Japan ensures the dealers have all the cash they require to do so, and the BoJ can and does then purchase securities from them even if no one else wants to. So the bonds are always sold and always have a ready buyer.

The debt, meaning the securities issued by the Treasury is the sum total of non-government financial savings. By reducing them we take away the only risk-free vehicle. I think it better to stop issuing debt with a maturity structure longer than 90 days and set the short-term rate permanently at zero. Yields will be no more than a few basis points.

As for spending on useless things, sure that’s a risk, but it’s a risk if we spend nothing, too. The private sector is awash in bad investments.

The process is basically this:

(1) Congress appropriates spending.

(2) US Treasury then authorizes the Federal Reserve to mark up the bank accounts of the vendors in the amount of the spending that Congress voted on. (Increases money supply.)

(3) THEN…

(4) The US Treasury issues treasury securities in the amount of the spending to restore the money supply to balance.

(5) Once a year (August), the Federal Reserve tells the US Treasury how much interest it will owe for the year.

(6) The US Treasury issues treasury securities in that amount.

This is Standard Operating Procedure.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

If you want to remove everyone’s savings, you would. “Debt” at the federal level is money created. Equity. Moolah. Only 11-12% of all US currency is physical cash. The rest are treasury securities.

You know that $17T+ National Debt (aka Debt Held by the Public)?

That’s a record of all the currency created by the US government since 1791 minus the currency destroyed (taxes). The $17T+ is in pension funds, university trusts, business, household, foreign bank and govt, and corporate bank accounts. (The FDIC doesn’t insure commercial bank accts for more than $250Gs, so these are risk free.) TO THE PENNY. It’s a record of what we own, not what we owe.

When the US Treasury pays off a treasury security–or “pays off the national debt”–it moves the principal+interest from a savings account at the Fed (where it has acted like a govt CD) to the seller’s checking account.

That’s it. Nothing more complicated than that.

Why does the government do this?

Because just after WWI, the government was concerned about the nation’s gold supply. When we were on the gold standard, all dollar bills were convertible to gold at the US Treasury. If you bought treasury securities, however, you couldn’t convert your money to gold until after the treasury securities matured. So this was how the government kept the gold supply from being at risk: it issued bonds ‘in lieu of’, and the gold supply was safe while we paid off WWI expenses. It is also why the government issued Liberty Bonds then: to get cash that could be converted to gold out of circulation and protect the gold supply, needed for foreign transactions.

Great explanation. Thanks!

Right. So why not just majik up the repayments right there at time of issue. Why bother with this whole once a year (August!) nonsense, when you can just account quite rationally at the time issue account for what the interest component and principle repayments are, credit them at issue, and save a whole lot effing about that magically turns up as someones overprice salary?!

Explain that Oh Great God of “I Make S### Up On Command!”?

Because that’s how the statute is worded.

Thanks, Ben. You and MRW have provided a great tutorial. Miguel’s analogy of majik is appropriate, the statutory wording being the spell that makes the illusory product, money, work.

All mediums of exchange rely on the supposition of majik in your usage, as people must – believe – in it. Those that think gold – bitcoin – rarity is “real money” believe that shiny metal – objects have majik qualities, that imbue it with the capacity to store value. Would a person that had never been introduced to the concept think, would probably say… hay a nice door stopper.

The difference between object fetishes and statutory law is – only one is accepted as taxes, one is only instantly accepted, the other is for individuals that believe an object can forestall values diminishment.

Budgetary stance cannot be determined from budgetary outcomes. You’re making a mistake a first-year econ student would know to avoid.

Yves says: “So understand full well why austerity gets such favorable treatment. In its current version, where central banks use QE and super-low interest rates to offset its bad effects, the result is rip-roaring asset prices and a continued shift of income and wealth to the rich.”

Yep, it’s plain old Class warfare dolled up as “extraordinary monetary policy”.

When is someone finally going to call a spade a spade?

The 3rd quarter number is an estimate, no? So maybe we shouldn’t dwell on it on much. If you extend the first chart back all the way to 1990, you see that this pattern of growth-contraction-growth-recession-growth is very common in Japan, so the latest GDP numbers don’t worry me that much.

I’m pretty sure that the primary objective of Japan’s QE program was to weaken its currency. The BoJ/MoF may not have had a specific exchange rate target in mind, but there is no doubt that a rate of 80 yen per dollar was unbearable for almost everyone in Japan. Something had to be done about it. In the past, they did foreign exchange intervention, but nowadays this kind of policy is a sensitive political issue. QE, on the other hand, is a less controversial policy and it seems to work pretty well for weakening one’s currency (it certainly did for the US, the UK and now the EZ).

When it comes to Japan, exports are the name of the game. Increasing the sales tax may well have been a mistake, but Japan now has a very competitive exchange rate and that could make all the difference.

Exports are the name of the game? Really? What part of Japans overall economy are they?

Can you give me several solid examples of when destroying ones currency has led to persistent strength?

China. Japan in the 1960s through 1985. The dollar spiking up in the early 1980s, which amounted to a weakening of yen v. dollar, was one of the best things that ever happened to Japan. They made massive gains in auto sales in the US and never gave that back. All of the Asian tigers post the 1997 Asian crisis. They kept their currencies cheap by design and racked up big foreign exchange surpluses.

Right now, the well-accepted thesis is that the global economy is suffering from a deficiency of aggregate demand. The continuous deflation (or rather noflation) supports this thesis for Japan pretty well, in my opinion. Higher net exports allow Japan to lean on other countries for aggregate demand. Among other things, this means more employment.

What would the alternative to QE be? More “infrastructure” spending? Perhaps building the space-elevator? More “growth”? More insider “spending”? More “good government” spending from one of the most corrupt governments on the planet?

What?

The alternative?

Repentance plus restitution of course!

1) Repentance: Temporarily ban new credit creation until all banks are 100% private with 100% voluntary depositors.

2) Restitution: Counter the massive deflation from 1) with an equal fiat distribution to all citizens metered appropriately to just balance existing credit as it is repaid for no net change in the money supply.

There’s no end of useful things to do. Removing invasive plants and animals, restoring habitat, subsidized or free childcare, long-term spending commitments for scientific or medical research, public health support for chronic diseases, more humane Alzheimer’s treatment, mass transit construction and operation, adult literacy education, drug treatment programs, more teachers in schools- the list is endless. Basically any good thing where people say “oh, we can’t afford that” qualifies, and that is a *lot*.

I recall China and Japan being criticized for their spending to build “bridges to nowhere” and “ghost cities” as an attempt to stimulate the economy. Personally, I would prefer a stimulus more akin to what’s Fair Economist’s suggesting.

Memories are short – I recall the previous rounds of QE in Japan being defended here, as against those who argued that, Central Bank sovereign omnipotence to print money aside, Japan’s reality was circumscribed by 2 blunt facts: lacking significant natural resources, Japan must export or die, and; Japan is a vassal of the US.

When Abe first revealed the size of the QE program I toyed with the idea that it was Abe’s way of proving to the US that ‘enough is enough’ vis a vis the spiral race to the bottom in global currencies. And indeed the Fed (and consensus opinion) have backed off from claiming QE ws the greatest thing since sliced (perhaps because the numbers so conclusively fail to support the claim). However, I’ve reverted to my prior stance, i.e., that BoJ simply does what the Fed tells it to do, thus BoJ jumped in within the blink of an eye to keep the carry going when the Fed wound down.

I no longer believe it a coinkidink that Japan has super-loose money and Germany the opposite, due to peculiarities of culture or whatever, rather, they act as 2 poles with the US between able to reverse polarity for each as needed. With US major banks gobbling up huge amounts of Treasuries just as QE ended, and petrodollars exiting the mix as well, the ECB cannot do QE without sending the US $ over the moon. The upshot is that Japan and Europe continue flailing away, while the US is happy to settle for ‘best in a bad bunch’.

I have no idea what you are talking about. This site has NEVER supported QE.

Memories are short – I recall the previous rounds of QE in Japan being defended here, as against those who argued that, Central Bank sovereign omnipotence to print money aside, Japan’s reality was circumscribed by 2 blunt facts: lacking significant natural resources, Japan must export or die, and; Japan is a vassal of the US.

When Abe first revealed the size of the QE program I toyed with the idea that it was Abe’s way of proving to the US that ‘enough is enough’ vis a vis the spiral race to the bottom in global currencies. And indeed the Fed (and consensus opinion) have backed off from claiming QE ws the greatest thing since sliced (perhaps because the numbers so conclusively fail to support the claim). However, I’ve reverted to my prior stance, i.e., that BoJ simply does what the Fed tells it to do, thus BoJ jumped in within the blink of an eye to keep the carry going when the Fed wound down.

I no longer believe it a coinkidink that Japan has super-loose money and Germany the opposite, due to peculiarities of culture or whatever, rather, they act as 2 poles with the US between able to reverse polarity for each as needed. With US major banks gobbling up huge amounts of Treasuries just as QE ended, and petrodollars exiting the mix as well, the ECB cannot do QE without sending the US $ over the moon. The upshot is that Japan and Europe continue flailing away, while the US is happy to settle for ‘best in a bad bunch’.

erstwhile a fiver

Don’t make up stuff about what we said. We never promoted QE and we never promoted Abenomics. We at most linked to an article by Ambrose Evans-Pritchard that was uncharacteristically over the moon about it, based on a similar experiment by Japan in the early 1930s that worked. But the difference was that Japan then didn’t have a bust banking system and (as we pointed out) Japan didn’t have every country in the world pursuing similar monetary experiments, which Abenomics was way too heavy on, and with everyone pursuing similar policies, the benefit of monetary games would be limited. Maybe shorter: Japan like England depreciated its currency earlier in the Great Depression than most countries did. That seemed to spare them the worst of the Depression. Everyone now is onto that trick.

I am not making stuff up. And the reason I am “Erstwhile” above is that a number of attempts to post as ‘Fiver’ poofed into nether space over a period of several days, leading me to believe I had been booted by Lambert for something he actually misread – yes and I did check later to see if the posts subsequently appeared. They did not. I was frankly surprised to see this one – even more so that my integrity has been challenged in absentia, as it were.

I do not make stuff up. There were a number of posts over a period of time on the subject of, or where comments meandered to, the subject of MMT, of MMT vs QE, and of the example of Japan vs the US and Europe, and specifically opinions offered by Yves to the effect that (to paraphrase) “Maybe Japan works a lot better than people credit”, or that “while you don’t like QE, it’s better than nothing, and there’s no inflation in Japan” and that those like, for example, Kyle Bass who in the time frame I’m speaking of was making a great deal of noise about the future of Japan, were more or less ‘blowing smoke’ because they simply failed to ‘get’ that sovereign CB’s render moot all other considerations when it comes to macro-money policy.

Now, I could presumably spend the next 2 weeks or months routing through post and comments, but I’d rather not. But I can say with complete assurance, Yves, that you often defended Japan’s monetary policies on the basis of the ability of its Central Bank to indefinitely borrow so long as it’s done domestically, and similar arguments. I’m sorry, but I was there, and I was one of the people then preaching Japan was headed for very big trouble. And sure enough, they’re now raiding major pension plans to ‘invest’ in foreign stock markets, their own market already utterly sated with BoJ direct and indirect ‘investments’.

That said. Thank you for having me back.

I fear for Japan.

The only comments I could think of that might be tepidly supportive of QE would have been in regard to the EMU which, given its rather unique situation, was in a position to see real benefits.

Well, the subjects of QE, EU and QE, and Japan and QE have come up many times over the last 5-ish years, and what you just said pretty much reflects the position I think Yves has generally taken, i.e., QE ‘works’ in a crisis and was instrumental re the Fed response to the GFC, but is not the best tool one might imagine, whereas I am dead set against doing anything that by nature empowers people that belong in jail while also catalyzing the mass transfer of claims on existing and future wealth from the lower classes to upper within every affected society, and between the undeveloped-through-emergent rest of the world and the US. I view the last 6 years of policy as the greatest waste of effort and resources in human history relative to what could have been achieved had the Fed emphatically refused the play The One Ring to Bind Them role Bernanke wrote for them.

QE would have worked for the EMU’s crisis (and still would), because a security purchased by the central bank might as well have never been issued so the program would have supported the financial positions of governments by reducing bond yields. But it wouldn’t do that for the U.S. or Japan because they have different monetary systems. I don’t personally recall Yves making any positive comments regarding QE in those two countries.

I was looking forward to seeing how the MMTers would explain the Japan implosion, but the explanations I’m seeing just aren’t manifesting into a coherent, rational logic for me. I don’t like this at all.

Like most industrial societies, Japan has a class of elites who must be protected and enriched at any cost. The fact is that it will happen, and will continue to happen, until the citizens get fed and put an end to it in some manner. In the case of Rome, the citizens opened the gates to barbarians. In France, Bastille Day. In America, the war of independence. This is not a monetary problem. This is a political problem, and it will be solved via some political means.

There is also the fact that the environment can not support industrial human society in its current form. Any political problems we may be experiencing are first co-incidental, and probably exacerbated by, resource depletion, pollution, and environmental collapse. Ironically, a “healthy” economy with lots of growth would only intensify the damage we are causing the environment, and consequently engender a more malignant political environment.

Any post proposing economic policies or detailing policy problems that does not address that is at best incomplete. Paraphrasing Masanobu Fukouka, humans are very good at taking a tiny part of a whole and ascertaining various facts about it, but they are very bad at applying that (incomplete and thus faulty) human knowledge in a way that that has an overall benefit. Not just MMT, but the entire “economics” thing strikes me as an unseemly attempt to string together fragmentary bits of disconnected facts into a coherent-seeming whole, that people, due to various cognitive errors, thereupon see as “true” explanations for why things happen. This way of seeing the world will only cause many times more problems than it can possibly solve.

MMT is not a theory of everything. It deals with monetary systems. It is not a theory of how to deal with an overleveraged banking system. You are asking a car to fly you to London, basically.

My economics knowledge doesn’t run all that deep, but my take on it is that it was never supposed to, not really anyways. People knew it was bullshit, but everyone is scared of things changing (I mean real change, the kind where there will be pain involved for many) and more than that there are a lot of very powerful people who have a vested interest in making sure things go on exactly as they have been. Keeping this mind, whatever garbage they say publicly doesn’t have to add up so long as it maintains the current economic structure. They could walk out and say that they could turn lead into gold and it wouldn’t matter so long as it keep the hustle going for a little while longer.

Peter Tasker’s blog site has some excellent background information on Takahashi and how it relates to today. Also some MMT tie ins. One lesson I see here that I have seen other places — once you really start stimulating through money printing it is near impossible to stop (France under John Law, Japan with Takahashi and Argentina under the Peron’s). Political forces that benefitted from moderate money printing always want more so they can stay in power. Interesting in the comment section he indicated that debt to GDP was 80% when Takahashi came in control so that is far different than the current 250% and that does not include unfunded benefits.

http://www.petertasker.asia/articles/back-to-the-future-japan-and-the-world-depression/

Back to the Future: Japan and the World Depression

April 19, 2013

by

Peter Tasker

«

»

Based on an article for Trust magazine – Summer 2013

Japan’s pre-war experience of deflation and reflation has several lessons for us today.

The first is not to be nihilistic about the potential for policy to make a difference. If the political will is there, reflation can gain traction with surprising speed.

The second is that successful reflation means a bull market in risk assets. As of 1931 Japanese stock prices were 70% below the 1918 high – a slump comparable to the gruelling bear market Japan has endured since 1990. Within two years of the turn to reflation, stock prices doubled and never looked back.

The third lesson concerns the necessity of a credible exit strategy, preferably expressed in clear numerical terms, rather than depending on the judgement of a single individual. Stimulus that becomes structurally embedded – whether in military spending or lavish systems of welfare – leads to disaster.

The fourth lesson is that conventional wisdom can be not just wrong, but dangerously so – especially when benign political ideals become intertwined with wrong-headed economic policies.

The commitment of Japan’s liberal elite to the deflationary gold standard created the conditions for militarism and national destruction. The commitment of today’s European elites to the deflationary euro may end up torpedoing the “ever closer union” that is their holy grail.

—————————————————————————————–

Japan is getting interesting again – thanks to “Abenomics” the reflationary policy package associated with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

Abenomics has a precedent – the policies of Korekiyo Takahashi, Japanese finance minister between 1931 and 1936.

According to Ben Bernanke, who is a scholar of the period, Takahashi “brilliantly rescued Japan from the global depression.” According to Hugh Patrick, the doyen of Japanese economic studies, Takahashi put together “one of the most brilliant and highly successful combinations of fiscal, monetary and foreign exchange policies the world has ever seen.”

So who was Korekiyo Takahashi? It is worth examining this remarkable man in detail, not least because senior figures in Japan’s current administration claim to be copying his approach.

Viscount Takahashi (pre-war Japan had a British-style honours system, subsequently abolished by the US occupation authorities) is sometimes referred to as Japan’s Keynes. However he was not a scholar or a trained economist. According to Richard J. Smethurst , author of a superb biography, he probably had no formal education at all!

Takahashi was born in 1854, when Japan was still a closed country under the rule of the moribund Tokugawa shogunate. He was the illegitimate son of a painter and a fishmonger’s sixteen year old daughter. Within days of his birth, he was put out to adoption with the family of a foot-soldier, the lowest rank of samurai.

Unlike commoners, foot-soldiers were allowed to have surnames. The adoptive father’s name was Takahashi.

On the brink of the Meiji Restoration, which kicked off Japan’s headlong rush to modernization, foreign traders and financiers flocked to the treaty port of Yokohama. At the age of ten Takahashi was sent to work as a houseboy at a British bank, where he quickly absorbed English and became comfortable with foreigners, as well as getting into trouble for drinking and gambling.

Two years later he travelled to California to further his English, only to be tricked by his homestay family and sold into indentured servitude as a grape-picker.

Bought out of the contract by friends, he returned to Tokyo. At the age of fifteen he was given a secure teaching position at a government school but “succumbed to the demon sake” and quit to live with a geisha. Perhaps it was this experience that inspired the Keynesian parable that he published sixty years later, just before he put his reflationary programme into practice.

“If a man goes to a geisha house and calls a geisha, eats luxurious food and spends 2000 yen, we disapprove morally. But if we analyse how that money is used, we find that the part that paid for food helps support the chef’s salary and the part used to buy fish, meat and vegetables then wets the pockets of farmers and fishermen. The farmers, fishermen and merchants who receive the money then buy food, clothes and shelter… From the individual’s point of view it would be good to save his 2000 yen, but when seen from the vantage point of the national economy spending is better.”

Takahashi’s first acquaintance with Japan’s elite financial circles came when he was given a job as a translator at the Ministry of Finance – where he shocked his co-workers by ordering in sake from a restaurant and drinking it at his desk.

In keeping with the turbulence of the times, Takahashi continued to move from responsible government jobs – he was Japan’s first patent commissioner and more or less wrote the laws on intellectual property – to dodgier areas of activity. He speculated in the silver market, set himself up as an unscrupulous stockbroker and led a group of brawling, hard-drinking Japanese miners to the high Andes. The silver mine he had purchased contained little silver and Takahashi ended up effectively bankrupt and living in a back-alley tenement in Tokyo.

Again, he was rescued by his connections and given a job at the Bank of Japan

Takahashi’s economic ideas were well formed by this stage. At a time when Keynes himself was still a schoolboy at Eton, Takahashi rose to the vice-governorship and implemented policies that, in the judgement of Richard Smethurst, were “more Keynesian than Keynes.”

Smethurst adds that Takahashi was both a Keynesian and a Hayekian at the same time. He believed that the government’s role was to create the conditions for growth, not to direct the allocation of capital within the economy. In particular he was opposed to increasing the share of military spending and maintained that Japan’s prosperity was best secured within the framework of the Anglo-American world order.

These ideas, consistently held throughout his career, ultimately cost him his life.

Takahashi’s experience and ease with foreigners made him invaluable to the new Meiji government. Proof of his talents came with the outbreak of the Russo-Japanese war in 1904. During extended stays in New York and London, Takahashi single-handedly negotiated a series of bond issues that allowed capital-short Japan to buy modern British warships and weaponry. His counterparties included Lord Rothschild, the American banker Jacob Schiff and the Scottish banker Alexander Allan Shand whom he had served as a houseboy back in Yokohama.

The results were spectacular – the sinking of the Russian fleet in the Battle of Tsushima and the first victory of an Asian power over Europeans since the Mongols laid siege to Vienna. Later Admiral Togo would tell the workers at Barr and Stroud in Glasgow, “You won the Battle of Tsushima for me.” In recognition of the role of finance, the Japanese government bestowed imperial decorations on Schiff, Lord Revelstoke (John Baring) and others.

Takahashi was in and out of public office through the first two decades of the new century. He was prime minister once, minister of finance five times and is the only governor of the Bank of Japan to have his portrait featured on a banknote. Throughout this period he argued for counter-cyclical growth policies, decentralization and a broad distribution of income. This pitted him against conventional opinion which favoured austerity and tight money and held that frivolous consumption weakened the Japanese economy.

The leader of the austerity faction was Junnosuke Inoue, a sophisticated, highly-educated Anglophile who rose effortlessly to the upper echelons of the financial bureaucracy. According to Lever of Empire, Mark Metzler’s wonderfully readable account of Japan’s pre-war monetary politics, “for Inoue it was almost as if recession was the natural state of narrow, constricted Japan.”

The contrast in temperament and background with Takahashi could not have been more pronounced. The two men started off on good terms, but grew apart ideologically in the 1920s when the economy, in Inoue’s own words, fell “from the summit of Mount Fuji to the bottom of Lake Biwa.”

Inoue welcomed the long deflationary stagnation that followed, which he believed was necessary to “tighten up people’s lax attitude.” As governor of the Bank of Japan, he hiked the official discount rate to 8.3%, where it stayed for five years, despite falling prices.

In 1929, the year in which Takahashi published his geisha house analogy, Inoue was lamenting that “luxurious living and the worsening of people’s thought” had only got worse. This was despite the fact that over the previous decade consumer prices had fallen 15% and wholesale prices 35%.

Like Britain, Japan had been forced off the gold standard by the First World War. Now, with disastrous timing, it was about to follow Britain back on. In preparation the government launched a massive austerity propaganda drive, which included movies, lectures, books and popular songs, such as the Retrenchment Ditty –

It’s the time, it’s the season,

All together, hand in hand (yes!)

Let’s retrench, let’s retrench…

You give up salt, I’ll give up tea (isn’t it so?)

Lifting the gold embargo (that’s right, absolutely!)

Until the joyful lifting of the embargo

The outcome was decidedly unjoyful. Lifting the embargo, necessary for a return to the gold standard, meant allowing the free flow of gold in and out of the country. A net outflow of gold was equivalent to contraction of the domestic money supply, which would inevitably lead to economic shrinkage. That is exactly what happened – on a huge scale.

In 1930 the economy went into free-fall. Nominal GDP plunged 20% in two years, unemployment surged and rural areas were devastated by falling prices. Brokers set up offices in hard-pressed north-eastern villages to arrange the sale of farmers’ daughters to houses of prostitution in the big cities.

The government fell, and shortly after Inoue himself was murdered by a right-wing terrorist enraged by the contrast between rural misery and plutocratic high living.

His personal disaster was to have identified himself so totally with the conventional wisdom of the times, which was strongly pro-austerity and pro-deflation. Japan’s disaster, and the world’s disaster, was that liberalism and democracy had become similarly identified.

With the failure of liberal austerity, the empowerment of violent radicalism became irreversible.

Metzler sums up as follows – “Inoue was tragically loyal to the ideas and forms of the liberal world order. By pushing the logic of that order to its full conclusion, he also helped to destroy it.”

By this time Takahashi had retired from public life to tend his bonsai, but he answered the call of duty and embarked on his last and most celebrated stint as minister of finance.

He immediately took Japan off the gold standard and closed the public deficit through bond issuance, not cuts in expenditure which had been the norm until then. He instructed the Bank of Japan to underwrite the bonds and feed them out into the market when conditions were propitious.

In contemporary terms, Takahashi depreciated the currency and combined fiscal stimulus with open-ended quantitative easing – all on a grand scale.

The result was a rapid return to growth and a stabilization of the debt-to-GDP ratio as government revenues soared. Under Takahashi-nomics, nominal output grew 70% between 1931 and 1936, while consumer prices rose just 18%.

But there was to be no happy ending, either for Takahashi or Japan. So successful was the reflationary programme that within five years it was time to implement an exit strategy. Takahashi, a strong advocate of civilian control of the military, had been critical of the Japanese army’s unbridled adventurism in China. It was clear that military expenditure would bear the brunt of his imminent fiscal squeeze, a prospect that was anathema to the hard right.

Early one snowy morning in February 1936, a group of fanatical army officers staged a coup d’etat in central Tokyo. A detachment of one hundred soldiers marched the short distance from their Roppongi base, now the site of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, to Takahashi’s residence in Aoyama. They burst in on him as he slept and shot and hacked him to death. It is a tribute to Takahashi’s stature that he was a prime assassination candidate at the age of eighty one.

The coup was soon crushed, but the nationalists were now dominant and Takahashi’s successor immediately doubled the military budget. Hyper-inflation and war were the inevitable result. As Richard Smethurst notes, “Takahashi was Japan’s last barrier to militarism.”

The rest, as they say, is history.

As for Takahashi himself, he may well have the last laugh. If Abenomics succeeds and if other countries follow suit, a humbly-born Japanese brought up in the Tokugawa era will have a powerful influence on the shaping of our world today.

Aiee, QE is not money printing!!!! This is a fundamental misconception.

Yep Yves… the full retard monetary collapse’niks are out in full force, like its a full moon.

The whole thing is as bad as some rapture zealots doing everything possible to bring on an event, self fulfilling prophecy’s comes to mind. Why???? Just so they can lord over everyone else and say ** I ** was right!!!!

Skippy… informing them of realities like balance sheet expansion and portfolio swaps just gets more gold buggery salivating for the business cycle trigger pull.

Somebody here in Japan wrote a blogpost at the start of “Abenomics” two years ago claiming that Abe’s new-found interest in the economy was merely a PR stunt. The purpose was to give him cover to pursue the right-wing, nationalist issues that he and his supporters really care about, and which derailed his first stint as PM. According to this theory, his advisers realized that nobody wanted to hear about school textbooks and patriotism again, but would respond to somebody trying to improve the economy. Unfortunately I can’t find the blog now, but at the time I thought it was a very cynical take on things, and actually, as did many, welcomed the return of Abe and the LDP after the Hatoyama / Kan / Noda DPJ disaster. A case of the devil you know is better than the one you don’t.

Two years on, and I’m not cynical about Abenomics being a PR stunt anymore. When Shinzo Abe, who has no background in economics, set out to find “experts” to help with his “plan”, every neo-classical educated, neo-liberal crackpot in Japan jumped at the chance. We now have the idiotic third arrow of textbook neo-liberal “reforms”, a Bank of Japan governor who thinks people don’t spend money they don’t have because they are waiting for prices to come down, endless rounds of pointless QE, and, of course, the stupidity of the fools and their consumption tax hike being let out of the closet where they had been locked away since 1997. It really is a PR stunt gone completely out of control, and the real question is whether Shinzo Abe is starting to realize that too.

QE on its face is not money printing. If the country’s central bank monetizes all the debt being issued by a country it seems to me that it is a round about way of money printing.

What is the difference between a country just printing money to pay its bills and a country that issues debt to get money to pay its bills, the un-independent central ban purchases all of the debt and receives interest on that debt, pays the interest is returned to the country and in the end the central bank forgives all of the debt.

In substance that seems to me to be money printing. After you cancel all of the actions out above you end up with additional money being issued.

It seems that the main problem is that the central bank is more interested in the health of the private banking system than in the general economy. It offers them abundant super low interest loans. These could be offered to students, and state and local governments if central banks truly acted as public banks for the public interest. And proceeds from these loans could feed back into the public interest instead of to shareholders and CEOs.

It also seems that in the case of the BoJ it is going down the path of ‘privatizing social security’ by buying govt bonds from pension funds while making them invest in equities. Blowing a bubble that will pop on the pensioners.

Right, Ishmael. But you aren’t going far enough with the “what is the difference”. What is the difference between a country that “issues debt” (prints bonds) and “issues money” (prints money)? Nothing at all. For they are one and the same thing. A bond is a dollar is a bond. A bond is not a promise to pay a dollar, but a promise that is exactly “the same” not-thing that a dollar is. A bond (ok, a Zero-coupon bond) is just a dollar bill with a date in the future printed on it. In FDR’s words: “Government credit and government currency are one and the same thing.” Modern economies (modern really meaning the last few millennia) can’t “monetize debt” because their debt is already money, and their money, as all money always must be, is debt.

Thanks for the Takahashi stuff. The important thing is fiscal – whether and how much and how the state is spending and taxing, not monetary policy/interest rate matters, of whether it is printing money or bonds. States have been printing money / running deficits for millennia, with rare exceptions of balanced budgets or surpluses, so you are right it is hard to stop, once started. But the smallest deficits tend to be “good deficits” caused by New Deal / Takahashi type “stimulus” spending. The biggest ones tend to be ones caused by austerity. Japan’s recent ones have been caused by incessant stop and go vacillation between the two.

I know this site has had many articles deeply critical of Paul Krugman. Before coming here I more or less relied on his analysis. Also before coming here I thought I understood “money”. Not that sure any more.

In any case, I recall one of Krugman’s articles from about 3 years ago where he argued that Abe’s spending policies were the right thing to do to move Japan out of its economic stagnation. If I recall the argument correctly, federal stimulus spending was good but that QE was better than nothing. He seemed to argue that this would pull Japan out of its economic crisis. Since it looks like Abe’s policy is not working I am curious how Krugman got it so wrong. Any clear answers here?

To my recollection the 1980s stimulus had two main effects – Japanese domestic property prices went off the scale and the export of low-interest Yen allowed many entrepreneurs to fund all sorts of dubious business offshore.

Japanese bank branches opened everywhere lending out their Yen at 1%, converting it to USD at 5% and funding the building of anything that might be sold.

What the Japanese had achieved was an ability to separate their domestic and international economies. The global splurge had less effect domestically than the property price rise because the notes were cancelled as they returned.

Is it the case that you can’t do that now? Why is the world not awash with Yen salesmen with suitcases?

I’m confused myself. First, if you have no debt. How is deflation bad.. things are cheaper? If goverments doesn’t need taxation for funding,why tax at all, it’s a political football any way? I promise I wouldn’t keep my potential tax as savings. Just the opposite is happening now I save to pay my taxes Why would Russia use arms against Ukraine..just use QE. And buy the country with their new paper creation?

Deflation is hugely destructive, far more than moderate or high inflation. I wish you would do some quick Googling rather than ask me for answers to basic questions:

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/explainer-why-is-deflation-so-harmful/

@Yves: “QE is not money printing, it’s an asset swap (securities for cash).”

And that “cash” comes from where? Central bank car washes and bake sales?

Of *course* this form of QE represents money printing – but instead of going to the little people it is going straight to the worst actors in the last crisis, that is, predominantly the TBTF banks. The Fed printed money in order to cover its side of the “asset swap” and used it to buy trillions of dollars of dodgy (and quite possibly toxic-to-the-core) MBSes from the banks, likely paying face value for the lot. Of course the opacity of such operations – the Fed only publishes total amounts spent, not “what’s inside that stinking container of MBS refuse” or how they priced it – is zealously guarded by the high priests, because I suspect they know that if the abble found out just what kind of garbage they bought and what they paid for it they might at long last rouse themselves from their myriad of distractive opiates and resolve to do something about these elite looters. But Bernanke is on record (2009) as saying the Fed “should overpay” for illiquid debt instruments in order to shore up the banks’ balance sheets, and I am almost certain the speech in which he said this was in effect laying out the roadmap for at least the MBS-purchase component of the ensuing multiple rounds of QE.

Now the official rationale is effectively “trickle down liquidity” – by replacing toxic garbage on banks’ balance sheets with pristine new-printed money the banks will be freed up to lend to main street, blah, blah – but with very little meaningful private-sector deleveraging have taken place in the past 6 years, the hoped-for hordes of eager borrowers never showed up, except for a select few areas, mainly subprime auto-lending and student-loan bubbles. So the overwhelming majority of the cash has been used by its recipients to engage in another massive bout of speculative-asset-chasing, i.e. in ways that are ultimately deleterious to the real (that is, productive) economy.

No. Please stop prating this “QE is printing money” nonsense. You really need to bone up on monetary operations. I am getting tired of using the comments section for tutorials.

See this and go do your homework:

http://www.cnbc.com/id/100760150

While your work regarding the many frauds surrounding the mortgage crisis was stellar, you nor the author of piece you cite understand money in the current monetary framework.

“The monetary base is defined as the sum of currency in circulation and reserve balances (deposits held by banks and other depository institutions in their accounts at the Federal Reserve).”

http://www.federalreserve.gov/faqs/money_12845.htm

QE either directly (no commercial bank deposit created) or indirectly (which also creates a corresponding commercial bank deposit) creates central bank reserves from nothing which existed before. In either case, banks can use the new central bank reserves to bid up the price of any asset they wish to purchase from another commercial bank (e.g. bonds, stocks, real estate), paying for it with the new central bank reserves (which only banks may hold as money), just as you might bid up the price of an apple with a new dollar bill if you could print them in your basement. In the indirect case, the pension fund or money manager indirectly selling the treasury security or MBS to the central bank can also use its new commercial bank deposit to bid up the price of anything they wish to purchase from anywhere.

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

As the Bank of England states in NO UNCERTAIN TERMS, “The central bank can

also affect the amount of money directly through purchasing assets or ‘quantitative easing’.”

You truly need to do the work to understand that you are being conned by the MMT crowd into believing functioning economies can create something from nothing (i.e. printing pieces of paper or crediting deposits), many of whom I’m sure don’t even fully understand the idiocy of their own beliefs.

Reseves are a dollar balance in a reserve account. Securities are a dollar balance in a securities account.

Wrong again, Kemosahbee!

Reserves (and I’m assuming you mean central bank reserves) are a form of base money, and can be converted into “dollars” by commercial banks. Thus, they are measured in dollar terms on balance sheets, but they are NOT DOLLARS! Securities are also NOT DOLLARS! They are SECURITIES, and like central bank reserves, are measured in dollar terms, but that measure in dollars can change instantaneously. Your belief system revolves around equating these financial claims, but they are not identical in duration or credit quality or issuer, as should be evidenced when in 2008 everybody wanted out of most securities and into dollars, or more accurately dollar-measured accounts least likely to disappear.

@ DCR: I am sure Ben meant government securities – otherwise you are of course right that issuer/credit quality is of the highest importance. MMT does not at all equate such different financial claims to government securities. But a basic point of MMT is that (US currency) dollars are securities, just like Treasury bonds. As FDR put it “Government credit and government currency are one and the same thing”. As Seymour Harris (largely forgotten Harvard Prof, leading early “bulldog” of Keynes, along with Alvin Hansen) said “government securities are quasi-money”. John Commons accurately classed both “bonds”(credit) & “currency”(money) as “futurity” back then. Governments cannot not make (short-term) rate decisions and thereby rigidly equate bonds with dollars / set an interest rate. Everyone used to understand MMT – and some people like those above – quite well – because it makes logical sense, unlike the massive botch of economics since the 60s/70s that seems to have confused you – as well as millions of others – as increasing amounts of nonsense, approaching 100%, were injected into Econ 101 courses everywhere

You are rather entertaining, I’ll give you that.

“As the Bank of England states in NO UNCERTAIN TERMS, “The central bank can

also affect the amount of money directly through purchasing assets or ‘quantitative easing’.””

Well, if the bank says that, you can take it to the bank…er….wait, maybe the junkies?

Why do you believe them? I thought they were crack addicts?

That’s what this post is about. How, in the real world, you can’t push on a string, in spite of whatever the BOE says. Reality has shown, for almost 5 years now, that it doesn’t work the way they say it does.

Why do you keep YELLING that it does?

Given how heavily he relies on that quote out of any additional context, I suspect he’s only read the first half of the first page in the .pdf. The latter half goes on to explain the process doesn’t work as he alleges.

@DCR

What are you talking about? QE, as practiced by the Federal Reserve, always creates a deposit in the seller’s bank (checking) account.

As the Bank of England article you linked to says:

That creates a deposit in the seller’s account, and as the Bank of England explains

And the BoE explains further:

Banks are not allowed to spend central bank reserves on “e.g. bonds, stocks, real estate.” And the deposit belongs to the seller of the asset, not the bank.

OK, so I set aside some time this weekend to give the CNBC piece Yves linked a critical reading and thinking-about.

Key takeaways:

1. There is simply no getting around the fiat ex nihilo aspect of the Fed’s side of of the “asset swap”. Unlike credit-money created by banks, there is no “automatic schedule to extinguish” the new monies as there is with credit money (via loan repayment or default). Quite simply the banks exchanged trash (‘illiquid’ MBSes which never saw anything resembling a market pricing attempt) for cash – new money created by the Fed, most of which got parked right back at the Fed as interest-earning reserves, but which *belongs* to the banks. No provision for the banks to repurchase any of the debt “when market conditions improve”, nor for the Fed to sell it back into the markets under similarly more-favorable conditions. In other words, the asset purchases appear to have been structured in a way which delays the loss recognition on the purchased debt as long as possible, that is, a decade or more, depending on the precise mix of mortgage terms involved.

2. On the mark-to-market aspect, it appears that the MBSes were exchanged sans any haircut, that is, at par. I base my ‘no haircut hypothesis” – apologies to physicist J.A.Wheeler for financialization of his famous “no hair hypothesis” w.r.to back holes – both on a Bernanke speech of 2009, predating the start of the Fed’s MBS purchases, and on the fact that we heard nary a peep of complaint from the banks about “excessive haircuts” on the debt.