By Lutz Kilian, Professor of Economics, University of Michigan; and Research Fellow at CEPR. Originally published at VoxEU.

Only a few years ago, many observers expected a steadily growing global shortage of crude oil. This shortage did not materialise in part because of the rapidly growing production of shale oil in the US. The production of shale oil (also referred to as tight oil) exploits technological advances in drilling. It involves horizontal drilling and the hydraulic fracturing (or fracking) of underground rock formations containing deposits of crude oil that are trapped within the rock. This process is used to extract crude oil that would have been impossible to release by conventional drilling methods designed for extracting oil from permeable rock formations. Shale oil production relies on the availability of suitable drilling rigs and skilled labour, which is one of the reasons why the US shale oil boom so far has been difficult to replicate in other countries.

US shale oil production has grown from about 0.4 million barrels a day in 2007 to more than 4 million barrels a day in 2014. This expansion was stimulated by the high price of crude oil after 2003, which made the application of these new drilling technologies cost competitive. The expansion of US shale oil production soon captured the imagination of policymakers and industry analysts. By 2012, the International Energy Agency projected that the US would become the world’s leading crude oil producer, overtaking Saudi Arabia by the mid-2020s and evolving into a net oil exporter by 2030 (International Energy Agency 2012). Pundits envisioned the US becoming independent of oil imports, net oil exports financing the US non-oil trade deficit, and consumers enjoying an era of cheap gasoline with a resulting rebirth of US manufacturing. My recent research, however, suggests that these visions remain far removed from reality (Kilian 2014).

Uncertainty About the US Shale Oil Boom

To gauge the importance of shale oil for the US economy it is useful to bear in mind that, as of March 2014, shale oil accounted for almost half of US oil production, but only about a quarter of the total quantity of oil used by the US economy. This magnitude is far from negligible, but to understand the excitement about shale oil one has to consider projections of future US shale oil production.

Publicly available projections of future shale oil production have to be interpreted with some caution.

- One concern is that increases in shale oil production are not permanent.

Sustained production requires ongoing investment. Projections by the US Energy Information Administration suggest that even under favourable conditions US shale oil production will peak by 2020 (at a level commensurate with US oil production in 1970) and then decline. Moreover, even the peak level would be far below what is needed to satisfy US oil demand.

- A second concern is that estimates of the stock of shale oil that can be recovered using current technology are subject to considerable error.

In the summer of 2014, for example, the Energy Information Administration was forced to lower its previous estimates of the stock of recoverable shale oil by 64%.

- A third concern is that it is not known how vulnerable the shale oil industry is to downside oil price risk.

This concern has become particularly relevant in recent months with the rapid decline in global oil prices. Shale oil production remains profitable as long as the price of oil exceeds marginal cost. There are indications that the initially high marginal cost of shale oil production has been declining substantially, as the shale oil industry has gained experience, but there are no reliable industry-level estimates of marginal cost.

In short, there is considerable uncertainty about the persistence and scope of the US shale oil boom, and there are many reasons to be skeptical of the notion that the US will soon (or indeed ever) become independent of oil imports.

Today, the US is the third-largest oil producer, slightly behind Saudi Arabia and Russia, with US crude oil accounting for about 10% of world production. Much has been made of the possibility of the US overtaking Saudi Arabia as the largest oil producer in the world, as the production of shale oil continues to surge. The implicit premise has been that being a large oil producer ensures a country’s energy security. It is easy to forget, however, that the US already was the world’s largest oil producer in 1973/1974 as well as in 1990. This fact did not protect the US economy from major foreign oil price shocks, suggesting that the focus on becoming the world’s largest oil producer is misplaced.

Imperfect Substitutability Between Different Types of Crude Oil

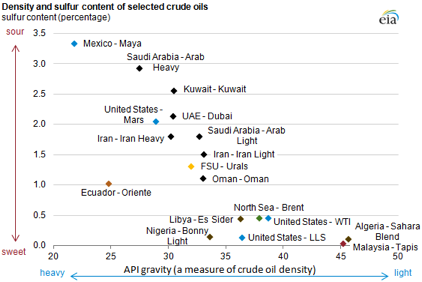

Even more importantly, the shale oil debate has largely ignored the fact that shale oil is not a perfect substitute for conventional crude oil, making comparisons across countries difficult. The quality of crude oil can be characterised mainly along two dimensions. One is the oil’s density (ranging from light to heavy) and is typically measured based on the American Petroleum Institute (API) gravity formula; the other is its sulphur content (with sweet referring to low-sulphur content and sour to high-sulphur content). Figure 1 provides an overview of how commonly quoted crude oil benchmarks (including West Texas Intermediate (WTI) and Brent oil in the North Sea) can be characterised along these dimensions. Shale oil consists of light sweet crude (at most 45 API), ultra-light sweet crude (about 47 API), and condensates (as high as 60API). Thus, not all shale oil is a good substitute for conventional light sweet crude oil such as the WTI or Brent benchmarks, and an aggregate analysis of the crude oil market tends to be misleading. In reality, the impact of shale has been far more complicated.

Figure 1. Classification of conventional crude oil benchmarks

Source: US Energy Information Administration.

Notes: MARS refers to an offshore drilling site in the Gulf of Mexico. WTI = West Texas Intermediate. LLS = Louisiana Light Sweet. FSU = Former Soviet Union. UAE = United Arab Emirates.

The US shale oil boom was preceded by a persistent and growing shortage of light sweet crude oil in world markets. US refiners responded to this trend by expanding their capacity to process heavy crudes that remained in abundant supply, becoming the world leader in this field. They were therefore taken by surprise when the US market was inundated with shale crude oil from the centre of the country after 2010. Not only was much of the refining structure ill-equipped to process this light sweet crude oil, but it proved difficult to ship the shale oil to those refineries on the coasts that would have been able to process it. With the development of shale oil in the interior of the country, large parts of the US oil pipeline infrastructure developed over the preceding 40 years had suddenly become obsolete, and rail and barge transport could not cope with increased demand. Moreover, exports of US shale oil that cannot be processed domestically were (and continue to be) prohibited by US law.

The resulting local excess supply of light sweet crude oil in the central US caused the WTI price of oil to fall below the Brent price. This discrepancy between domestic and global oil prices resulted from a breakdown of arbitrage between domestic and imported light sweet crude oil. There are signs that the US refining industry is gradually responding to these price differentials. Reconfiguring the US refining and transportation infrastructure, however, is a costly and slow process. For the time being, therefore, the evolution of the US price of oil is inextricably tied to improvements in the US refining, pipeline, and rail infrastructure.

In sharp contrast, US retail fuel prices have remained integrated with the world market in part because US refined products such as gasoline or diesel (unlike domestically produced crude oil) may be exported freely. As a result, the widely noted decline in US domestic oil prices relative to international benchmarks such as Brent, has not been passed on to the consumer in the interior of the country. This point is important because it removes the basis for any notion of a rebirth of US manufacturing on the basis of low-cost US gasoline and diesel fuel.

The Beneficiaries of the US Shale Oil Boom

Thus, the main beneficiary of the US shale oil revolution has been not gasoline consumers or, for that matter, domestic shale oil producers, but the US refining industry, which enjoys a competitive advantage compared to diesel and gasoline producers abroad because of its access to low-cost crude oil. In fact, refiners have every incentive to preserve the status quo and to prevent a lifting of the US ban on exports of domestically produced crude oil. An additional beneficiary of the shale oil revolution has been the transportation sector, notably the railroad industry, and the industries directly serving the oil sector. In contrast, the macroeconomic effects on real output and employment have been small, given the negligible share of the shale oil sector in the US economy. It is fair to say that there is no support for the notion that shale oil has been a game changer for the US economy. One area in which the shale oil revolution has made a difference is in reducing crude oil imports on the one hand, and increasing exports of refined products on the other, thus improving the US trade balance (and as a side-effect dampening the effect of foreign oil price shocks on the US economy). Of course, these improvements are small compared with the overall US trade deficit.

The (Lack of) Impact on the Global Price of Oil

It may seem that the rapid decline in the global price of oil after mid-2014 may be attributable to sharp increases in US shale oil production, providing direct evidence of the impact of the US shale oil revolution on oil prices after all. Although shale oil is not being exported, it replaces US crude oil imports, reducing the demand for oil in global markets, as do US exports of refined products. Some observers have gone as far as suggesting that shale oil may have become a victim of its own success in that it caused a sharp drop in global oil prices. There is no credible support for this interpretation. Similar price declines also occurred in other industrial commodity markets at the same time, suggesting that the cause of the oil price decline has not been specific to the oil sector, but that it mainly reflects a weakening global economy in Asia as well as Europe, possibly amplified by the decision of many oil producers to preserve oil revenues by increasing oil production in response to falling oil prices. This view is also consistent with the comparatively small magnitude of US shale oil production on a global scale.

References

International Energy Agency (2012), World Energy Outlook 2012, Paris: OECD/IEA.

Kilian, L (2014), “The Impact of the Shale Oil Revolution on U.S. Oil and Gasoline Prices”, CEPR Discussion Paper 10304.

Haha. Not even a passing mention of water aquifer destruction. And poisoned aquifers will never ever ever recover. They can’t be steam cleaned like an oil spill. Oh well, we’ll just build a water pipeline from the Artic once all the US water is undrinkable and unbathable.

That’s the modern industrial/American way: when you run out of wood in the winter, start burning the house down just to keep warm a few minutes longer.

Don’t forget the Arctic “C”. (yes, global warming pun.)

The critical variable here is the U.S. export ban which, with this next Congress coming in January, will drop or certainly ease export restrictions.

The energy companies never envisioned the primary market for shale oil as being the U.S., but overseas markets, where higher prices can be realized. Even if the shale oil boom produced almost total independence from foreign oil imports, the energy companies would have eventually alleviated that condition by shipping overseas.

Most of the Alaskan supply gets shipped to Japan, and yet we still import oil. There’s an historical precedence for this.

Key phrase: “Sustained production requires ongoing investment.”

To “kill” Shale Oil doesn’t require low, low oil prices, just a price low enough (with a threat to go lower for good measure) that investors are deterred from financing more drilling. It seems that that price is about $80.

Shale Oil wells that are already producing will almost certainly keep pumping until they are dry. Since the lifetime of each well is about 2 years (as far as I can determine), most of them will have run dry within 12-15 months.

And, the world economy has slowed but my sense is that it hasn’t fallen off a cliff like 2008-9 (which caused oil prices to plummet).

Looking forward, the next ordinary OPEC meeting is in June (they can have special/emergency meetings between in the interim). It’ll be interesting to see if Saudi Arabia continues to ignore the pleas of other OPEC members to join them in stabilizing the price at a higher level.

=

=

=

H O P

Lifetime of the fracked wells is a bit longer than that, but production drops by about 50% per year. So they’re getting completely uneconomical by the fifth year, when they’re producing 3% of first-year production, but still have the same operations costs.

This country it would seem is no longer capable of the long term planning required for genuine investing. This is enough to make you wonder who if anyone is driving the train. One could plausibly argue that domestic energy supplies are so important to national security and the economy, the 2005 “Halliburton Loophole,” an exemption for gas drilling and extraction from requirements in the underground injection control (UIC) program of the Safe Drinking Water Act, was a regrettable necessity. But if that were the case why in the divinity’s name would we want to sell to people beyond our borders the oil and gas we very possibly are poisoning future generations to obtain? Why would we want to pay – at a minimum – the environmental costs connected with the Keystone pipeline to facilitate the sale of US and Canadian oil and gas?

And having made that decision, why would we allow Saudi Arabia to destroy an industry we have already paid such a horrendous price to create by dumping cheap oil on the world market? Why would we allow them to destroy the market for electric cars and hybrids, the transition to which is essential if the country is ever to regain control of its foreign policy? This sellout of the country’s future started more than 60 years ago when Eisenhower was compelled to institute tariffs on Saudi and other OPEC nation cheap oil so domestic producers could continue to profitably drain the country’s reserves. (Or 90 years ago when Harry Sinclair was allowed to pump oil from the naval petroleum reserves.)

This sellout of the country’s future has to end NOW!

The sellout certainly won’t end on its own. It will have to be ended by force. But what kind of force? And developed how and deployed against whom? Those questions seem worth thinking about and researching to me. And different theory-action groups can develop and deploy different kinds of force against different targets according to their different theories.

Obviously, nobody is driving he train. Nobody is in charge. This sort of behavior benefits nobody and it’s a case of stupid people being stupid, combining for an even stupider result.

Comparatively small magnitude? The price of oil has halved in six months and the largest member of OPEC is reversing its stance on “shale does not concern us” attitude since Nigeria stopped exporting to the U.S. The denial is strong with Mr. Killian.

If I understand the article correctly, it is claiming that shale oil is not by itself responsible for the price decline.

I think he is inviting us to think that a worldwide stealth price-deflation/ silent depression is what is driving down commodity prices, including the price of oil. And attributing that price drop to shale oil is therefor to look for the car keys under the streetlight rather than where they fell in the dark.

I thought that Saudi had decided to inject sea water into some of its older, more depleted oil wells and is pretty much forced to keep pumping the oil out or risk contamination?

Twilight in the Desert shows the former (for entire fields, not wells), but I don’t know about the latter.

Oooh. Nobody really knows how much oil the Saudis have left because they haven’t published real data since 1982 (32 years ago!!!) I’m not sure why they think keeping it a secret will help them.