Yves here. Please read past the finger-wagging “private lenders are (barely) starting to come back to Greece, better not spook them” talk. This piece provides a useful overview of how the composition of lenders to Greece has changed over time. You can see how significant banks once were and how they were quiet deliberately displaced by various “official” creditors.

By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel and previously, an Economic Analyst in the DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission (ECFIN). Originally published at Bruegel

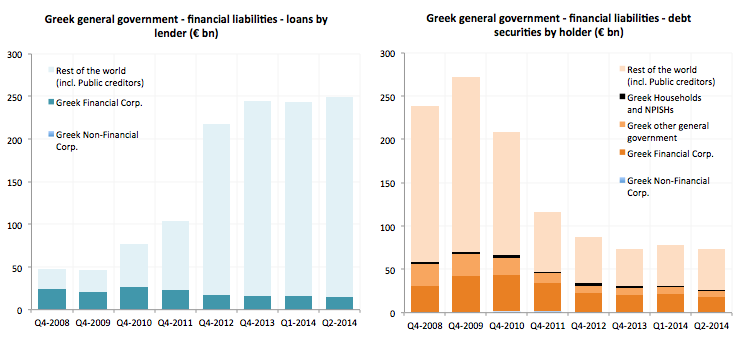

Since the start of the crisis, the structure of Greek debt has changed considerably (almost 80 percent of government financial liabilities are now accounted for by loans, against slightly less than 20 percent back in 2008). At the same time, the weight of public creditors has increased among the creditors of the government. Figure 1 shows a breakdown of the Greek general government financial liabilities across the main creditor sectors (with public creditor included in non-residents). At the end of 2013, debt due to official creditors amounted to 216 billion of loans (IMF/EU loans) and 38 billion of securities (under SMP). This means that, at the end of 2013, official creditors accounted for about 94 percent of the total loans due to non-residents and 89 percent of the total securities held by non residents.

Source: central bank of Greece, financial account, general government financial liabilities

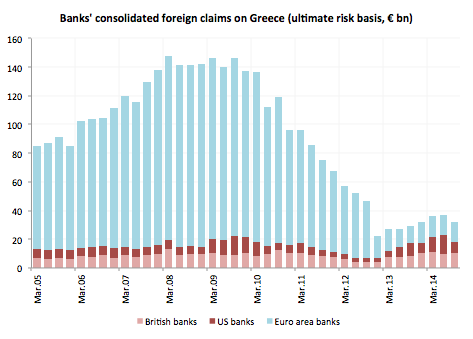

But the government is not the only Greek sector to which foreign investors are exposed, and official creditors are not the only investors in Greece. After Greece came under market pressure and eventually obtained an EU/IMF macroeconomic financial assistance programme in 2010, foreign banks started to rapidly reduce their exposure to Greece (figure 2). Euro area banks’ consolidated foreign claims on Greece – which peaked at about 128 billion euro in 2008 – reached a low of about 12 billion euro in September 2013. UK banks’ exposure reached a peak of 13 billion in March 2008 and dropped to 4.3 billion in December 2012. US banks’ exposure instead was about 14 billion in September 2009 and down to 2.5 billion at the end of 2012.

Source: BIS; consolidated ultimate risk basis. EA includes AT, BE, DE, ES, FR, IE, IT, NL, PT

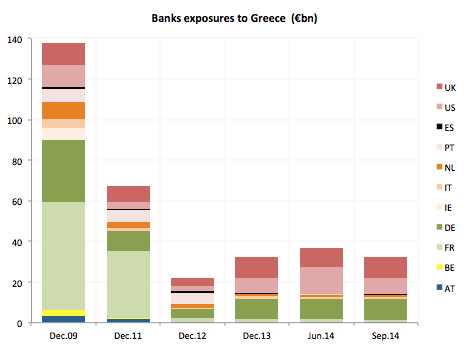

Interestingly, US and UK banks have been increasing their Greek exposure again, since March 2013, reaching back to levels not very far from those of end 2009 /early 2010. US banks’ exposure to Greece as of September 2014 was in fact 8 billion (down from 13 billion in June) and UK banks’ exposure was 10 billion. Euro area banks have behaved very differently and total exposure to Greece has in fact continued to decline in almost all countries. Even more interestingly, the only country where banks have been continuously increasing their exposure to Greece since 2013, is Germany. German banks’ foreign claims on Greece in fact reached 32 billion in March 2010, dropped to as low as 3.9 billion at the end of 2012 and were back to around 10 billion in June 2014. Therefore the recent increase is small compared to the historical level, but it has been continuous (at least until September 2014).

Source: BIS, consolidated ultimate risk basis

As of the latest available data (September 2014), euro area banks’ exposures to Greece amounted to 96.6 million for Austria, 29.4 million for Belgium, 1368 million for France, 10203 million for Germany, 55.9 million for Ireland, 800 million for Italy, 923 million for the Netherlands, 263 million for Portugal and 301 million for Spain.

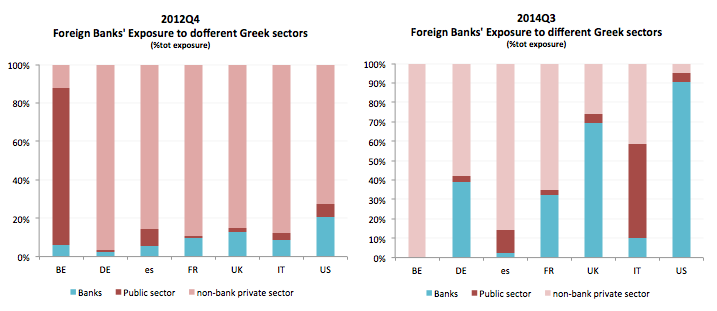

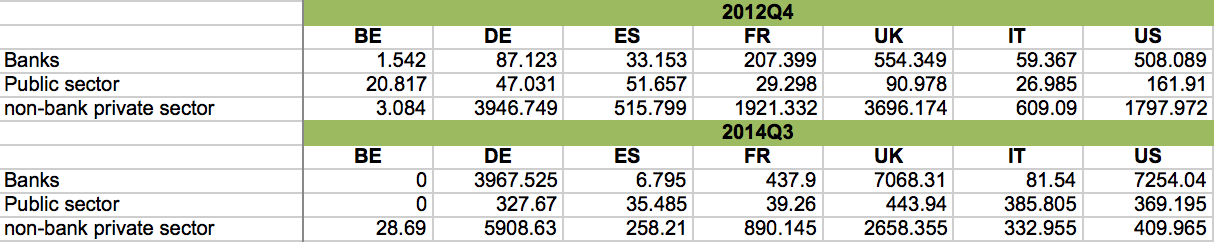

The composition of such exposures, however, varies across countries and has significantly changed over time. Figure 3 compares the exposure of selected foreign banks to Greek sector as of september 2014 versus December 2012 (chosen as a starting point because so that comparison is made between two post-PSI dates).

In 2012, exposures to the Greek private non-financial sectors accounted for the largest share of banks’ exposure to the country, with the exception of Belgian banks. In 2014, exposures to Greek banks have significantly increased as a share of total exposures in all countries but for Belgium and Spain. In terms of absolute numbers, only Belgium and Germany have increased their exposure to the Greek private non-financial sector. In absolute numbers, also exposure to the public sector has increased everywhere (apart from Belgium), but the only country where public exposure has significantly increased as a share of the total is Italy.

Exposure of banks in different countries to Greek sectors (€ million)

Source: BIS; consolidated, ultimate risk basis

Anybody who has followed the development of the euro crisis know about the important increase in the weight of public creditor for Greek government debt. This data show, however, that since 2012 (when the ECB introduced the OMT programme) private investors have been timidly and slowly coming back also to Greece. While exposures of euro area banks are still at very low levels compared to the pre-crisis period, it is tempting to interpret this as a first trace of normalisation and resume in confidence, which the present political turmoil risks to revert.

‘Alexis Tsipras’ “open letter” to German citizens published on Jan.13 in Handelsblatt, a leading German language business newspaper.’ ( Title of the english language version) :

http://syriza.net.gr/index.php/en/pressroom/253-open-letter-to-the-german-readers-that-which-you-were-never-told-about-greece

Excuse me if this has been posted or a link posted in other recent comments sections here.

‘Our target is, rather, the country’s stabilization, balanced budgets …’

He’s taking a riff from Frank Roosevelt’s 1932 campaign against Herbert Hoover!

And we all know how that turned out …

This shows clearly how between 2010-2013, about 120 billions in euros of public debt, mainly in the form of greek securities held by eurozone banks were transferred to loans held by official creditors. Greece “rescue” was the rescue of eurozone banks (already in a weak position) at the expense of eurozone taxpayers, mainly german, and french. This has been well known by NC readers but this post gives us the maths. By transferring that amount of debt, the Troika not only rescued eurozone banks but introduced a new element of conflict in eurozone policy: financial confrontation amongst taxpayers in different countries. This is just another step in the neoliberal agenda. First, europeans were reduced to be treated as consumers that have to compete in labour markets with low mobility amongst countries (Bolkestein directive etc.), and now as financial competitors. Tax transfers not only take the shape of financial debt transfers. The absence of fiscal and labour armonization and tax heavens do an important part of the job. Everybody knows who are the winners. Not large corporations and banks, just the 0,1%.

This can end in to ways: i) Eurozone and EU breakup. ii) it migth give birth to a new european conscience that translates in an european-wide political answer. Rigth now the first option looks much more likely. Nevertheless, we have witnessed how parties like Syriza (Greece) and Podemos (Spain) with a similar view migth produce the seeds of the new conscience. It should be of crucial importance for this parties to find coreligionists in other EU countries and found an european-wide political movement.

It is sad to see how blind have been the traditional social-oriented parties. Blind because they didn’t see or because they din’t want to see. They are paying the consequences now.

States lending to states … it’s a real-world example of the blind leading the blind, or children having children.

Will Germany this time round play the role that the US/Entente powers did after WW I, dogmatically demanding that Germany pay reparations amounting to 900% of GDP, despite the obvious mathematical and practical impossibility of doing so?

Greek debt is ‘only’ 175% of GDP, but it’s still unmanageable. And Greece has no factories on the Ruhr to occupy. Let’s hold a conference in Versailles and fudge all this somehow!

drinking the merkel koolaide again I see…

900% hmmm….German gdp in 1914 was 50 billion marks…although the germans paid less than 20 billion over 12 years between 1921 and 1933, there was never any giant number as you suggest…on paper there was a top number of 269 billion marks but most of it was a phantom zero PIK, with the actual cash payments due at 700 million marks per year…a little hard to create the GIANT CRASH as claimed by the gerbulytes of the world…with a 50 billion mark economy having to pay out 700 million marks in hard cash….which they never actually did…got it cut down to 10 cents on the dollar and then Hoover let them not even pay that ten seconds after they “finally” agreed to pay something….

oh…and the germans didn’t really think it was so bad taking so much from anyone when they sent in the reds into russia to over throw the monarchy and then cut that deal on March 3, 1918 where they ate up about half of russias manufacturing capacity and a third of its arable land…when they were doing the grave dance it was ok…

germans hate to pay…there is zero basis for them having an investment grade rating…none…they have never paid anyone anything…they simply get people to lend them fresh money or roll over owed debts…

and then they come up with ESA 95 to hide the pension deficits they have along with those of Finland and the Netherlands…

http://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/pdf/scpops/ecbocp132.pdf

ah….never mind…the jesuits were right…by age 7 your meme is set…

Yes. On the news last nite Merkel is reported to have told Greece that it is unacceptable for one country to burden the taxpayers of another country. Meaning that German taxpayers are ultimately on the hook for a Greek default. The whole question of odious debt is being endrun. And it goes beyond odious. The system brought itself to a screeching halt and only bailed out the banks. The question that is put forward is Who is going to pay back this money? It is the wrong question simply because the old system has been demolished. It would have been more efficient to demolish all the old money along with it. Those “debts” no longer have any rational significance. Where can the blowback of debt default finally end up? Central banks have absorbed it as fast as they can. And they can go on using QE. So this means privateering banks will be saved and ultimately taxpayers will pay. And then what? Doesn’t it logically follow that privateering banks will also have no future? It’s the system. The money is the IUO for the system. When the system goes down, why does the money survive? Nevermind.

Greek sovereign debt is not odious. The question of odiousness is determined by factors on the borrower’s end, not that unpopular banks may wish to collect the debt to the immediate social detriment of the borrowing nation. It may be unpayable and probably is in great measure. Were Greek debt odious, the Greek populace would not have suffered as much over the past years. No, the borrowed money went to legitimate national priorities as determined by legitimate popularly elected democratic government. When existing creditors and potential future lenders decided that Greek debt was tremendously risky, the impact of financing difficulties went directly to socially important – even critical – areas like health care, pensions and the like. Had criminals simply stolen most of the borrowed funds the adjustments would have been much easier on the populace since truly useful public expenditures would not have been so heavily impacted.

But that is my point. It is odious to demand repayment when the system for repayment has been demolished. Growth will not happen. Ever again.

The investor class know Greece can’t recover. They are just playing the game to maximize their extraction of wealth … one suspects financiers are lobbying central bankers to Bail Them Out and punish the Greeks on the way by. Why not? It’s been a working strategy for a while now.

I struck the rant about credit being a Bankster weapon. Too obvious for this sophisticated crowd.

“The investor class know Greece can’t recover. They are just playing the game to maximize their extraction of wealth…

This is what makes sense to me. I can’t see how Greece pulls itself up by its bootstraps. Nor can I see the lenders doing so out of the goodness of their hearts. We’ve seen it in the wealth extraction in this country. It isn’t just to put a nice painting in the livingroom. It’s to slice and dice and financialize everything, because it makes money. And it isn’t the man behind the curtain you’re not paying attention to; it’s the family out on the street with kids who are never going to go to college.

I know, I’m very dumb. But I remember one of those slicers and dicers on Charlie Rose way back, one of the new multibillionaires who’d got there doing some daring finesse of the markets, saying: “Nobody really understands this stuff.” If you don’t really understand (or want to understand) who you are hurting, maybe you shouldn’t be allowed to do it.

Banks of USA, UK and Germany are holding the debt now. They must have invented a piece of paper that pays a part of the charge they are putting on Greece and they must have found investors to buy that paper, not through a Stock Exchange Heaven forbid, but through commission-earning financial intermediaries, the “no-questions asked” chaps. I suppose anyone with hot money and no place to put it might be attracted but rest assured there is no risk sticking with the bank. Indeed, I would not be surprised if they sell the paper before they buy the debt.