By Richard Vague, the managing partner of Gabriel Investments and the chairman of The Governor’s Woods Foundation, a non-profit philanthropic organization. Previously, he was co-founder, Chairman and CEO of Energy Plus, and also co-founder and CEO of two consumer banks, First USA and Juniper Financial. He is also the author of The Next Economic Disaster, a book with a new approach for predicting and preventing financial crises. Originally published at Democracy Journal

On the morning of September 8, 2016, the Wenzhou Credit Trust, one of the many trust companies in China, went into default. The firm discontinued all new lending and suspended redemption and interest payments on its trust certificates, the equivalent of deposits made by its customers.

At the time, the failure didn’t seem all that unusual. A handful of trust companies—“shadow lenders” that make loans, often the riskiest ones, outside of China’s conventional banks—had done the same in recent years. But within a week, another trust company went into default, and the following week, so did seven more. Angry trust-certificate holders protested in Wenzhou and Chongqing but were quelled by police. Those protests hardly seemed noteworthy at first—for years, there had been hundreds of protests and disturbances across China—but it turned out they presaged something new.

Within a month, more than 50 trust companies defaulted. The protests escalated and spread throughout the country. In the panic, new real-estate lending plummeted, putting more downward pressure on real-estate prices and hurting local economies. The Shanghai and Shenzhen stock markets plunged. The prices of iron, steel, coal, copper, aluminum, and other commodities—including oil—accelerated their downward spiral.

The government of China, which in recent years had tolerated these failures as part of its attempt to introduce more risk into the system, dramatically reversed course and intervened, injecting funds into these lenders and assuring customers that it would stand behind these institutions. This calmed equity markets, but commodity prices continued to sag and the renminbi fell, bringing the specter of devaluation.

By winter, the impact had shattered markets and companies throughout Asia and Australia, and markets were in retreat in Europe and the United States.

The Great Panic of China was in full swing.

The future, of course, doesn’t have to unfold this way. China, the world’s second-largest economy, could still act to prevent much of the above from happening.

But what cannot be changed is this: China, fueled by runaway lending, has produced far more housing, steel, iron, and a host of other goods than it knows what to do with, amassing unprecedented levels of overcapacity and, by my estimate, making a staggering $2-$3 trillion in problem loans in the process. And since GDP growth is more a measure of capacity being created than capacity actually needed, even China’s high rate of GDP growth, fueled almost entirely by continued ultra-high levels of lending growth, compounds rather than solves China’s fundamental overcapacity problem.

Which means that the global economic boost from China, the world’s only major growth engine since the crash of 2008 in the West, is rapidly diminishing and will soon largely end. The only question is how.

China’s bad-debt problem is unprecedented in scale, but not in nature. In the United States in 2007 and 2008, we saw our own economy crumble under the weight of bad debt. And the system didn’t know what hit it: On the eve of our own collapse, even though more than $1 trillion of bad mortgages had already been made and major financial fallout was inevitable, banks’ loan-loss provisions—the amount they set aside to cover bad loans—were near an all-time low, while consumer net worth and the stock market were at all-time highs.

Neither of the two dominant economic theories of our time forecast the coming storm. The doves—those more in favor of lower interest rates and government stimulus—were sanguine, unconcerned by rapid loan growth. The hawks—those more focused on curbing the money-supply expansion through higher interest rates—were sounding dire warnings of inflation. Both were wrong, but neither has since changed its theory.

Our 2007-08 meltdown was entirely foreseeable, despite claims to the contrary. It was not a “black swan” event. Examining the historical record leads to the conclusion that major financial crises can be anticipated so long as you’re on the lookout for the red flag of rapidly rising levels of private debt. If we are to avoid repeating history, we would do well to observe the Chinese predicament, understand its implications for the global economy, and apply lessons to our own economy.

Our Private-Debt Problem

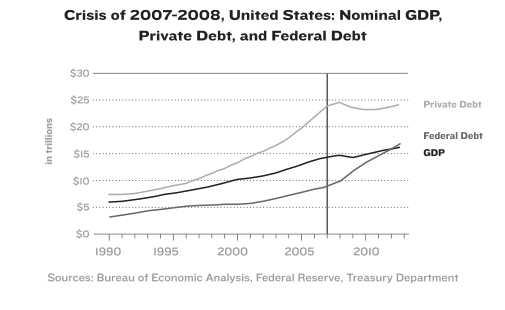

The ongoing debate in Washington over government debt misses the point. In the years leading up to the U.S. crisis, the remarkable fact was not an increase in the level of federal debt, but the explosion in the size of privatedebt relative to GDP, which rocketed from 120 percent of GDP in 1997 to 165 percent in 2007. By contrast, federal debt barely changed, declining from 63 percent of GDP to 62 percent during that same period. Private debt is the sum of consumer debt, including mortgages and business debt. In my view, a healthy private-debt ratio would be no more than 125 to 150 percent of GDP.

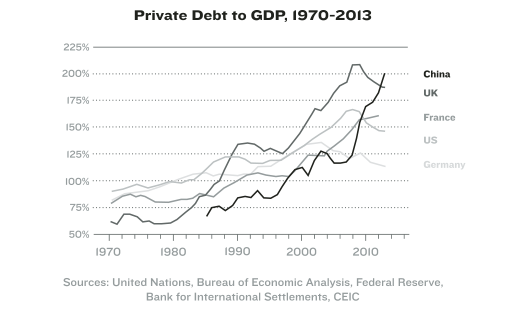

While many observers missed the signs, some saw that private debt was somehow key to the American crisis, since the rapid increase in home mortgages was widely discussed as a culprit. And a closer look at the historical data shows that this relationship between private data and financial busts appears to be universal: When we examine financial crises in other countries, we see that—even when these crises were attributed to other causes—private debt was the fundamental factor. Private debt can be good when overall levels in a country are low or moderate, and when, for example, it is used to finance projects whose income can repay that debt. The problems come when private-debt growth is too rapid or reaches levels that are too high.

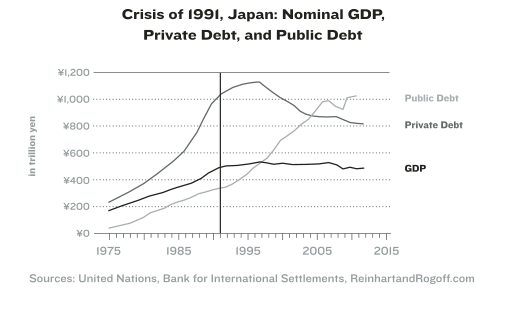

That certainly was the case in Japan in the years before its 1991 financial crisis:

The chart shows a familiar picture. In the years before the crisis, Japan saw a major spike in private debt. And that’s the same picture we see in crisis after crisis.

As I’ve previously written, there is a formula to predicting these crises. A financial meltdown is probably on the horizon if the ratio of private debt to GDP rises by roughly 17 percent or more over the course of five years and exceeds 150 percent. That rise in private debt will likely fuel runaway growth before the crash (think the 1920s, or Japan’s boom in the 1980s). But those gains will be evanescent. Driven by private-debt growth, they’ll eventually give way to a financial crisis.

In past crises—1929, Japan in 1991, the United States in 2008—high government debt was not the culprit, since in each case the ratio of government debt to GDP was generally flat or declining. Nor did they correlate with any of the long list of other widely cited causes, including current account deficits and interest rates. (Rapidly rising government debt generally becomes an issue after a crisis, as tax revenue plummets and deficits rise, government “safety net” programs get higher use, and governments counteract declining private spending with higher government spending.)

Why does runaway growth in private debt lead to financial crisis? First, because it means that far too much of something has been built or produced. It was primarily housing in the United States in 2008; in Japan in 1991, it was primarily commercial real estate. And second, because it means far too many bad loans have been made in the process. By 2007, for example, the U.S. banking system had roughly $1.5 trillion in total capital, but an estimated $2.5 trillion in problem loans.

If too much capacity and too many bad loans are the problems, the solutions are time and capital: time for organic growth to absorb the excess capacity, and capital to repair banks and borrowers. Monetary and fiscal policies might soften the blow, but since they do not address those two fundamental issues, they cannot solve the underlying problem.

The Potential for Crisis in China

The problem for China in 2015 is that it looks a lot like the United States in 2008 or Japan in 1991.

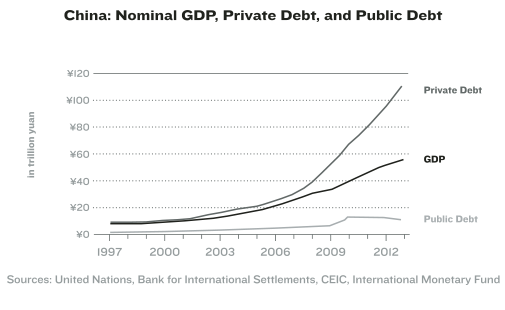

The growth in the ratio of private debt to GDP over the last five years is an astonishing 60 percent, and that ratio now exceeds 200 percent. China’s runaway debt growth has primarily been in business loans, and now its total business loans are greater than in the United States, even though, based on exchange rate, U.S. GDP is 82 percent larger than China’s. (For China, we use the term “private debt” for the sum of business and consumer debt, though some analysts refer to it as “non-government debt.”)

Quite simply, China has produced and built far too much capacity, through overinvestment in steel and cement firms and in accelerated housing development. In the process, it has amassed the largest buildup of bad debt in history.

The cause of the accelerated rise in private debt starting in 2008 was the collapse of the export market that had fueled China’s growth to that point. From 1999 to 2006, China’s exports-to-GDP ratio had exploded by 95 percent. China’s net exports, as measured in dollars, were the highest in recorded history. But they were growing on the shaky foundation of the debt-fueled expansion of the West that led to the crash of 2008. When that demand evaporated, China’s exports evaporated too. Addicted to its rapid expansion, China built a lot of real estate and produced lots of goods—both unjustified by actual demand—to fill the export hole, all financed by an unprecedented rise in private debt that is almost certain never to be fully repaid.

As a result, China is now sitting on top of the greatest accumulation of bad debt and overcapacity in history. According to the Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance, more than one in five homes in China’s urban areas is vacant, with 49 million sold but vacant units, and 3.5 million homes that remain unsold. Behind those vacant and unsold units is private debt, both loans to developers and mortgage debt. Housing values in China increased on the same perilous trajectory as in the United States before 2008 and Japan before 1991—and they have now started a similar decline. Meanwhile, real estate was 6 percent of U.S. GDP at the peak in 2005; today, it is as much as 20 percent of China’s GDP.

There are other red flags. China produced 8 percent of the world’s furnace iron in 1980; it now produces 61 percent, even though the rest of the world still continues to produce every bit as much as it has in the past. As China’s iron production accelerated in the period from 2002 to 2011, iron prices increased twelvefold in response to debt-fueled demand. (Increases in debt cause increases in prices.) But now that iron capacity has piled up beyond need, prices have tumbled by over 50 percent, and the excess capacity is so great that even the demand generated by rapid credit growth can no longer prop prices up. Also, China used more cement in the period from 2011 to 2013 (6.6 gigatons) than the United States did in the entire twentieth century (4.5 gigatons).

These are but a few of many examples. Researchers at a Chinese state planning agency said recently that China has “wasted” $6.8 trillion in investment. Overcapacity is so significant in many sectors that it will take years for it to be absorbed by organic demand. Ironically, this problem is compounded by China’s own continued high growth rates, since high GDP growth is a measure of the creation of additional capacity even if that capacity is not needed.

Good and sound loans, by definition, result in commensurate GDP growth. So when private-loan growth outstrips GDP growth, much of that excess—from one-quarter to one-half, based on evidence from other crises—will be problem loans. Based on this formula, China today is likely to have an estimated $1.75 trillion to $3.5 trillion in problem loans—a figure well in excess of the $1.5 trillion of total capital in China’s banking system.

Of course, China’s banks and shadow lenders are not reporting bad loans close to this amount. But neither did U.S. banks: On the eve of the U.S. crisis, banks were making loan-loss provisions at very low levels. Lending booms create the false appearance of prosperity, and fraud and corruption can make the picture even prettier.

Some dismiss these warning signs, noting that many economic prophets wrongly made the same dire predictions for China during the late 1990s. But there’s a big difference: In 1999, China’s overall level of private debt was 111 percent of GDP; today, it’s almost double that, at 211 percent. In 1999, it had plenty of room to power growth through continued private-debt expansion, and the debt boom in the West fueled unprecedented export demand. The opposite is true today.

China’s Future—and the World’s

China’s slowdown is already underway. Nominal GDP growth has already slowed from over 15 percent in 2011 to around 7 percent in the last year—and some analysts believe it’s actually closer to 4 percent. The decline will continue to play out, perhaps dramatically, over the next three to four years. How well or badly it plays out, however, depends on the approach the government takes to simultaneously managing both the short-term problem (slowing growth) and the longer-term problem (the overhang of private debt).

The trouble for China is that these two challenges summon conflicting responses. GDP growth in any economy is largely dependent on private-credit growth, yet the Chinese private sector is massively overleveraged. Ramping up credit might reverse the slowdown but will further increase bad debt and compound the ultimate problem; reining in debt, on the other hand, would help the debt problem but slow down growth.

True, China’s economy is largely a closed system that can make—and suspend—its own rules, which means China’s leaders can prop up their lending system for a time. (Even Japan was able to prop up its banks for several years after its stock market collapse.) What they can likely no longer do, however, is effectively prop up real estate and commodity prices. Over time, because the decline in real estate and commodity prices is evidence of China’s overcapacity and those assets are collateral for so much debt, it will be China’s Achilles’ heel.

The fundamental problem is that China has misused debt to grow far faster than income growth prudently allowed. While on the surface the choices look bad, China—with its vast assets and low central government debt—in fact has the tools to navigate this crisis yet. China’s impulse is to return to practices that have succeeded in the past, so it’s difficult to imagine it abandoning the three pillars of its past growth strategy: exports, business credit growth, and infrastructure spending. But there is now a diminishing return from each: exports are constrained by low global demand; businesses are already overleveraged; and China has already built too many roads to nowhere.

Since these will not suffice, China will likely consider other growth channels: increasing consumer credit growth; ramping up other categories of government spending such as military spending; encouraging continued migration of rural populations to the cities; and perhaps even renewed devaluation. But these options, if employed, will still collectively fall short.

China’s consumers reportedly do have low leverage, but household debt is already growing much more rapidly than is prudent, and is ultimately limited by household income. And consumer debt in China may be higher than indicated due to high levels of unreported, informal consumer lending. Further, China’s consumers have put a major portion of their savings in real estate—many own several apartments—so the ongoing decline in housing values will discourage consumers from taking on significant new debt.

Increased government spending could help pick up the slack, especially if it is focused on areas where there is not already too much capacity, such as military spending. But even here, the scope and pace of additional spending are inherently limited by operational realities. China hopes to bring hundreds of millions more rural Chinese citizens to the cities, to increase both wages and housing demand. But these plans crucially depend on job growth to support these migrants, and job creation has been a leading casualty of slowing exports. Finally, devaluation works best when matched with high global demand, risks driving out badly needed foreign capital, and, in any event, would likely be matched by competitive devaluations from other nations.

Both “rebalancing” and “reform” are cited as important parts of the solution. Rebalancing is needed—China’s growth has been far too dependent on investment by its businesses as compared to consumption by its households. But rebalancing is hard work that will take years, not quickly enough to reverse China’s decelerating growth. Reform of business practices is needed as well, but that too will be very difficult, and likely won’t happen fast enough.

Some believe that through continued high productivity gains, China can sustain high growth without worsening its private-debt picture. But in recent years private-debt growth has almost equaled China’s increased productivity, calling into question the sustainability of those increases absent continued high private-debt growth.

Panic and the Path of Contagion

Because there are few good choices to adequately boost growth, the continued decline in commodity prices and real estate will make the problem loans in China’s banks worse, as a massive amount of the country’s private debt is secured by commodities and real estate. Based on its recent behavior, the Chinese government will likely address deteriorating bank loan quality with an overt and broad guarantee to consumers for deposits and possibly also wealth and trust certificates. It will also quietly fortify these lenders with capital. If China pursues these policy choices, it will indeed avoid an immediate financial crisis. But it ultimately cannot reverse the trend of decelerating growth over the next three to four years—perhaps to a level approaching zero—and China will be left facing a “lost” generation of very low growth similar to the last 20 years in Japan.

The question facing the rest of the world is whether there will be a crisis in other countries because of China’s troubles. What will the path of financial contagion be?

Financial contagion is not some mysterious force that overtakes the healthy and unsuspecting. Any impact on non-Chinese companies and countries will come from: 1) overlending to troubled Chinese banks and businesses; 2) an overconcentration of exports to China; 3) a dependence on high commodity prices; and 4) a currency devaluation necessitated in an export-oriented country because of a devaluation by China.

Most countries in the Asia-Pacific region have significant export concentrations to China and will be adversely affected by China’s slowdown, as will many countries in Africa and South America. Europe has exposure too, especially in the area of high-end automobiles and luxury goods. The United States has more limited exposure, but some sectors such as high-tech and construction have significant sales in China.

Although there are allegedly low levels of foreign debt in China, these levels may be underreported; banks that have lent to companies or banks in China face real risk as growth decelerates. Hong Kong, Singapore, and the UK are among those with the highest lending exposure to China. Countries dependent on high oil and other commodities prices are also at risk. If China devalues its currency, many of its export-oriented Asian neighbors would be forced to follow suit—and in fact may act to devalue ahead of China—bringing the specter of a banking crisis to these countries.

Reckoning with Private Debt

In the 1980s and early ’90s, my formative business years, the media regularly trumpeted the news that Japan was ascendant and would eclipse the United States as the world’s business leader. When Japanese firms purchased iconic properties such as Rockefeller Center in New York and Pebble Beach golf resort in California, it was confirmation of that trend. In the 1980s, Japan reached 18 percent of world GDP. Today its share of GDP has fallen to 7 percent. We now know that its seeming path to dominance was paved with runaway private debt.

While China’s trajectory might not be the same as Japan’s, there are profound similarities. China has had years of runaway private-debt growth, and its GDP growth is now decelerating. There is no doubt that China, with a population over 1.3 billion, will be an increasingly important player in the world, economically and otherwise. But there has been a tendency to overestimate what China can achieve economically over the near term. America’s economy is almost twice the size of China’s, and our relative influence will continue to reflect that difference.

Indeed, we should take a more balanced view of China. With its growth, China has had a significantly higher profile in a variety of policy areas. It has been more assertive in military matters. It has expressed a desire to have the renminbi take its place as one of the world’s reserve currencies—in essence competing with the U.S. dollar for a bigger role in the world’s economy. U.S. policy-makers have struggled with how to respond to this assertiveness. Much of it should be unsurprising, given China’s rise to its current position as the world’s second-largest economy. But even with its successes, China now presides over enormous and in some respects unprecedented internal problems, and we should understand the limitations they impose on what the country can achieve in the near term and resist making policy blunders by overestimating its relative strength.

So what should China do? My recommended course is for the country to directly address not slowing growth, which is only a symptom, but the real problems: overcapacity and excessive private debt. In this scenario, China would prudently slow both lending and growth, allowing demand to begin to catch up with overcapacity. What’s more, China would also preemptively recapitalize its lenders.

However, my recommendation goes well beyond China’s past cosmetic bank cleanups. It needs to take the further step of requiring lenders to broadly, quickly, and decisively restructure debt with overburdened corporate borrowers—to provide, in other words, real debt relief and restructuring that allows those corporations to resume productive investment, not simply accounting sleight of hand. Otherwise, high debt will linger for years as a long-term drag on China’s economic prospects.

Large-scale corporate debt relief would be complex and difficult. But the lesson from Japan’s experience, where the private-debt-to-GDP ratio reached a staggering 221 percent, and timely and meaningful debt restructuring was not adopted, is that it’s necessary. A generation later, Japan’s private-debt-to-GDP ratio is still a stifling 170 percent and remains the neglected central issue in Japan’s lackluster growth.

China may never undertake such systemic private-debt restructuring, but it is the surest path to revitalizing its beleaguered business sector, remedying overcapacity issues, stabilizing prices, and restoring reasonable growth. By alleviating rather than simply disguising China’s high private-debt-to-GDP problem, it would leave corporations in a much better position to lead renewed (and, hopefully this time, more measured) growth after the slowdown.

Lessons for America

Runaway private debt brought America to its economic knees in 2008. It did the same to Japan in 1991. And it is in the process of doing the same to China. Yet the schools of economic thought that dominate thinking and policy-making in Washington pay scant attention to private debt. And so our economists and politicians will continue to err in forecasting crises, and will also make inadequate repairs after the fact. Just as runaway private debt causes crisis, the overhang of private debt after the crisis constrains growth. Private debt has been underemphasized by economists in some measure because of the view that for every borrower there is a lender, and thus private debt “nets” to zero. This view neglects consideration of the distribution of debt: Lenders tend to be institutions, and borrowers tend to be those middle- and lower-income households most needed to sustain economic growth. Private debt has also been underemphasized because public debt seems more our public responsibility, and private debt seems more off-limits—the domain of the private sector and “the invisible hand.”

Seven years after our own crisis, private debt in the United States stands at 143 percent of GDP—lower than its apex of 167 percent in 2008, but still high. The high level of private debt in the United States represents a drag on economic growth, most starkly evident in the almost nine million of the nation’s 53 million mortgages that remain underwater. In fact, private-debt levels across the globe remain sky-high—not that anybody’s paying attention. The piling up of private debt over decades smothers demand and dampens economic growth.

China’s economic challenges offer the United States an opportunity to learn and recalibrate our economic thinking. Like China, we should now concentrate on scaling back private debt (which we did not do in the aftermath of the 2008 crisis). We need to act differently this time around if we are to avoid having our recovery swamped by the next slowdown (from China or anywhere else). Debt relief in the form of restructuring or partial debt forgiveness should be seriously considered as an option. What if we were to let lenders write down underwater mortgages over an extended time frame (30 years)? While less necessary today, if this had been done in 2008, it would have made an enormous difference in the trajectory of the recovery.

Our policy-makers should move beyond the fixation with public debt and turn their attention to the true problem of private debt. They should recognize the inadequacy of the timeworn tools of monetary and fiscal policy and lead a discussion of strategies—especially restructuring—to address the key issue of historically high private-debt levels. Indeed, low private debt, combined with low capacity (the supply of housing, factories, etc.), was the precondition for the economic boom we experienced in the post-World War II decades.

China’s downturn will only add to our challenges. The modern world has had four major economic engines—the United States, China, Europe, and Japan—which together constitute 60 percent of world GDP. While the United States moves toward respectable growth, both Europe and Japan—also hobbled with high private debt—are struggling to show any progress.

But it is China we should be worried about. China is facing a generation of dramatically slower growth. Its slowdown will cause trouble for its trading partners and lenders across the globe. And while the economic impact in the United States will be softer than in any other major country, China is now so large that we too will feel it.

The question is whether we will also learn from it.

“those more focused on curbing the money-supply expansion through higher interest rates—were sounding dire warnings of inflation”

Well, there are those that recognized that monetary inflation already happened at that time. The fact that the cpi did not show high inflation rates over the past 30 years but still always positive inflation does simply show that it is a very limited instrument of measure to base monetary policy on, as productivity gains would actually lower prices considerably. When money supply grows consistently faster than the economy, we have a problem in one from or another (the believe that there is a free lunch to be had with monetary stimulus is a fallacy and short term thinking). It is simply the so called “kicking the can” or “after me the diluvian” mentality.

A lot of that printed money has gone overseas, to the most remote, or labor-excessive areas.

Thus, you don’t see price inflation back home.

But if you don’t have the global reserve currency, and you haven’t accumulated a lot of it through being a good servant of the empire, it’s risky. You might still succeed, but you have to be careful, because that money gets bottled inside your sovereign area.

Writing down underwater mortgages benefits one group of citizens over another. It seems unfair that only those who chose to, and were given the means to, overextend themselves should be rewarded. A fairer solution would be a Basic Income Guarantee to all citizens, which could be used to pay off debt.

Nice and succinct analysis. I first visited China in the late 1990’s and was astonished to see the number of massive (and very poorly constructed) hotels and commercial buildings sprouting up in very obviously poor and low priority third tier cities. Despite the glitz, there was very obvious over-development and most of them were half empty. I naturally assumed that all the Chinese boosterism at the time was nonsense, and that there would be a financial crash quite quickly, mirroring that which had just recently occurred in Thailand/Malaysia etc. So I was astonished and somewhat humbled to witness wave after wave of development completely transform the country in an incredibly short time. The crappy new hotels with their wonky fake gold sprayed bath accessories I stayed in back then have probably long ago been demolished and replaced with even glitzier ones.

But of course that doesn’t mean my original gut feeling was wrong. Perhaps a good strong recession in the ’00’s would have been the best thing that could have happened to China, it might have put the brakes on the rise in debt. But it has been increasing massively, and maybe even more than the figures suggest. I’ve Chinese friends who tell me that there is a vast network of mutual borrowing which never appears on the books – simply people borrowing off friends and family, using property as collateral (and who knows how many times the same property has been used as collateral), all to pursue yet more speculation. A very close friend of mine quit her job because she was making so much money (15% per annum) from an investment with a ‘friend’. I pointed to her every online source I could on ponzi schemes and the impossibility of that type of return over the medium to long term, but she just shrugged her shoulders and said ‘We have no choice but to trust him, everyone is doing it’.

I think one of the most dangerous elements of the Chinese over investment boom is not in the naked figures for debt, but in the psychology of the wealthier Chinese elements of society. Almost without exception, they do not see their long term future in China. They all seem to assume something terrible will happen, and they have their bolt hole in the US, Australia, London, Lisbon, Cyprus (any country which will offer citizenships for cash or investments). When things start looking dodgy I think we could see an outflow of people and cash on a scale never seen before. Even though I would trust the CCP (which so far has shown a remarkably steady hand on the tiller) to do everything reasonable macro economically to deal with a major downturn, I don’t see how they can deal with so many wealthy and influential people, including of course many senior Party members, simply catching the next flight to San Francisco with everything liquid they can take with them. It could get very nasty.

‘…with everything liquid they can take…’

That might explain why all those Yuan blue and white jars going for $25 million or more.

All you need is 40 of them and you can take your billion asset to Cyprus (Hey, why doesn’t Greece do that?”

The thing is, at all those fancy auction houses in London, New York, etc, you pay 20% or more buying and 25% to 30% selling. Or you can try smaller places, where you might see a lot of strange looking Song Ru pieces, when there are less than 100 known in the whole world today.

Yes indeed. When the 2007 crash happened in Ireland there were stories going around of BMW’s stuffed with art and antique jewellery going on one-way ferry trips to France for semi-permanent residency in lock-up garages there. Any kind of mid-level (i.e. not too easy to source) art or antiques are a great way to hide cash from tax authorities or creditors. Its no secret that the Chinese nouveau riche fetish for expensive watches is motivated at least partly by this. I’m sure this would be a major driver behind the remarkable climb in values for collectables the past decade or so.

I suppose the one good by-product of a Chinese crash would be for art or antique lovers to pick up beautiful pieces cheap. Many of the worlds greatest collections of art were built up in post war/conflict years as formerly wealthy people sought to make their assets liquid, so objects of beauty became relatively ‘cheap’.

Not sure about art or antiques, however if the smart watch paradigm takes hold, there may be a window to pick up high-quality mechanical watches cheaply. This happened during the transition from film to digital cameras, where for a short period of time one could pick up film cameras that were previously unattainble for anyone who was not either a professional in the field, or rich, for relatively cheap prices. Not altogether unsurprisingly, the market for high quality film cameras has experienced significant gains since this time, especially for film cameras that don’t rely on batteries.

The author is intelligent and earnest but misses the fact that everywhere increased private debt is a de facto substitute for rising wages and a means of creating “profits” that aren’t there. If most Americans were starved of credit, their standard of living would plummet. Politicians would have to answer awkward questions about why this was so, questions that no one in authority wants posed, no less answered. Businesses would have to plow back profits into plant, equipment, inventories, research, and development, rather than just borrowing to pay for all that while pocketing current profits as top executive salaries and dividends. Credit has become our means of sustaining the promised life of 1950s and 60s America, the carrot that keeps people from asking too many pointed questions or thinking outside the parameters laid down by the current system. It is the siren song that keeps the “haves” around the world enthralled to American hegemony. It is not a simple question of “sound” economic policy.

As long as we remain under a Forced Free Trade regime, if we had the dryup of credit you suggest which forced bussinesses to have to plow back profits into plant, equipment, inventories, research, and development as you suggest; every penny of that plowback would be invested in China, etc. and precisely zero of it would be invested within US borders. If we wanted any of it invested within US borders, we would have to abrogate and cancel every Free Trade Agreement and Treaty we are stuck in, and withdraw from every Free Trade organization we are stuck in. Only then would made-in-America be able to exclude products made overseas with their Comparative Advantage in slave labor, zero pollution control, zero social security, zero worker safety, etc.

No Protectionism? No hope, and no point trying to do anything about anything.

I’ve been advocating protectionism. I’m sorry. I think we need it kind of badly.

“Yet the schools of economic thought that dominate thinking and policy-making in Washington pay scant attention to private debt.”

You know, because everybody’s debt is somebody’s asset….(sarc)

I agree Mr. Levy. Nothing wrong with taking out a home loan – but when it became a desperate substitute for income replacement, or wealth generation, and everybody was going to get rich by borrowing more and more money…well, as the material girl says, “we are living in a material world” and if promises were wings, pigs would fly…

And of course, its funny who gets bailed out, and who doesn’t…

Why does this scenario look familiar to those who have endured the past eight years in the the United States? Is this financier too uninfluential to call out the American economic disease directly? The United States could act as an economic engine if the US elites were not so perversely greedy and stupid. US elites have moved things back from the brink in the past. But the insistence on ideological purity in the economic elite is now sacrificing everything. The private debt that is dangerous is the corporate debt that the very fretting elite have themselves incurred. That destruction of places for people to work is what will trigger consumer debt collapse just like layoffs triggered housing debt collapse.

Wonder if corporations will call for a private, corporate debt jubilee?

At some level, high levels of private debt is due to two things…Ability to lend and willingness to lend. There is ALWAYS plenty of demand for borrowing. There will always be a sufficiency of people willing to borrow their way to the poor house. And because of the “heads I win, tails the shareholders lose,” nature of business management, there are plenty of businesses willing to borrow.* The financialization of the economy has meant that there is plenty of money looking for a place to go, so ability (except during the very height of the financial crisis) is not really an issue. So what exactly has fueled the willingness to lend? Many factors IMHO. There is the increasing opacity of the bond market with an alphabet soup of ways to hide toxic loans in bonds, all with the blessing of the bond rating companies. There is the fact that the Great Depression is something too far in the past to be taken seriously…The high inflation of the 70s seems a much more pressing threat to the powers that be. Which helps to encourage the regulatory capture of the government, along with the corrosive effect of way too much money in politics. And that leads directly to the moral hazard of the belief that the Fed and the Treasury will bail the financial “industry” out of it’s bad decisions. I’m sure there are other, important factors.

*Not to mention management (especially PE types) willing to loot companies.

The AIIB-Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank-is attracting Western partners, to the chagrin of the U.S.Government, which prefers to squander its resources on destroying countries, trying to incite Russia into starting WW3-with the E.U. as a target-as well as trying to call the shots in the world, like a colonial power of yesteryear. Being in denial with the handwriting on the wall, is delusional at best. It may have taken the “Superpowers” of the past many years to fade-where are they today-but here in the 21st Century, even the latest ideas are obsolete before they reach production.

Take what Dick Vague says with a huge grain of salt. Under his watch during the late 1990s as CEO of Bank One’s First USA card division he wiped out 20% of Bank One’s stock price in one day due to his mismanagement of the First USA card operations, which led to a major executive purge both at First USA and Bank One, whereupon Jamie Dimon was brought in to clean up his mess. Just how bad were things at First USA? First Card (FIrst Chicago NBD) chargeoffs were worth more on the secondary market than First USA chargeoffs were. And that’s just a tiny piece of what went on.

Agreed. Anyone who starts an article with a detailed prediction is bound to be wrong. Our species does not do forecasting – even the weather report is seldom more than partially right.

And he has overlooked the great advantage China has from its one-party government. Its always the same people setting the policies. They can’t blame anyone else. That is a marvellous way of focusing the mind on good remedies.

Again putting the cart before the horse. A very apt metaphor as everyone is talking about the problems of the cart and only casually mentioning the fact that the horse is lame.

The mistake that all economic analysis makes is in believing that the World is driven by money/debt creation where as it is energy that drives all activity on Earth. It was cheap almost free energy from FFs that allowed banking/finance to grow so big and now it arrogantly believes that it is separate from and superior to energy. There is no monetary policy that will create cheap almost free energy but if by some miracle a new cheap almost free energy source is brought online we will find that the Global economy could be resolved.

Yves – Your book and analysis is very insightful and accurate and it all happened the way you say but you would do well to factor energy into the picture a lot more.

The repeated dismissals of Chinese growth and predictions of collapse after 38 years of profound Chinese development strike me as absurd.

That makes the odds in the pessimist’s favor, don’t you think.

X^38 (where x < 1) can become very small. Tough to be right 38 years in a row.

I like your thinking… Give the guy time to be right. Of course, just these last few days we have the results of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank drawing in the UK, France, Germany, Italy and Switzerland against the wishes of the US, evidently there are policy makers who find China too promising to be dissuaded by the US.

They are only absurd if you have never read any Chinese history. The entire history of China is one of periods amazing technological and economic progress, with periodic catastrophes which set it back centuries. And there is nothing extreme about the Chinese example. Any economic historian can point to examples of societies apparently setting off on a process of inexorable growth and progress, and then falling back with astonishing speed. Its quite easy to spot the process when it occurs, although almost impossible to predict when exactly the crunch will occur, and what the process will look like. The only true ‘unknown’ is if the society has the structural strength to pick itself up and advance forward again (as European countries have done after they’ve self-immolated), or whether it will unravel and go into longer term decline or stagnation as we’ve often seen in South America.

I think trying to highlight private versus federal debt is good, but familiar criticisms of the federal debt to GDP ratio apply here equally.

Since private debt merely redistributes private wealth (it doesn’t create it) it seems pertinent to ask “good for whom?” A debt scheme that collects many small contributions from a large number of citizens may obscure who money is being distributed away from, and may appear “better” than one that solicits major contributions from only a few individuals. I think whoever states “debt can be good” needs to specify the exact conditions under which it is good, and I don’t think “makes a return to investors” fits the bill. Note we are talking about aggregate debt, not one person’s individual debt. Clearly debt that can be expunged can serve an individual. But assuming that shows ‘aggregate private debt is good for society’ is entirely unjustified.

I’m with James:

What seems to have been forgotten in all of this is that the willingness of the United States government to deficit spend for several decades and the rest of the world to buy US treasuries has helped considerably to keep global economic growth on the road. Now the Neo-Conservative dominated Democratic and Republican parties who understand nothing about sectoral balances applied nationally or globally are turning off the government money creation tap. This is bad for the citizens of the United States but good for the world globally in the long term because it will force other countries to re-balance their economies and particularly the ones that depend heavily upon exporting.

You hit a good point.

The United States government has been willing to deficit spend for decades now.

And this is what we see.

Maybe we ask, is it a problem of no (or not enough) deficit spending, or is it that we haven’t deficit spent it in a more positively distributed way?

The US does not need foreign bond buyers to finance Federal spending. Indeed, recently, the Chinese have been net sellers of Treasuries.

Suggest analysis move upstream a notch and consider whether Chinese demand is constrained by a simple lack of desire for goods and services, or if demand is being suppressed by reduced growth of bank and shadow bank-created “Money”; i.e., private debt service capacity constraints under the current monetary system?

I view the Chinese edition of financial crisis and its anticipated aftermath as merely another chapter in a book of crises that have unfolded over the past 25 years that stem from a largely private debt-based global monetary system that is deeply flawed. My question is what a better alternative would be?

Because of the massive prospective dislocations beyond China’s borders, I would very much like to hear economist Steve Keen’s, Bill Mitchell’s and Randall Wray’s views about these developments in China and possible solutions.

Finally, as an aside, consumers are dependent upon corporations, businesses and government for their incomes. To consider consumers to be a source of significant incremental debt capacity when businesses are overleveraged, real estate overbuilt, and the banks and shadow banks tapped out and under-capitalized relative to anticipated losses, seems to me to be an overly optimistic expectation.

Thank you for this article. Much to think about.

Michael Pettis has written quite a lot on this topic in his very informative blog. Its quite clear that Chinese consumer demand has been very significantly repressed for decades as part of deliberate government policy. As an obvious example, the lack of a pension system compels people to save a high proportion of their income.

I would note that in his opinion (if I understand his arguments correctly), there is more than sufficient repressed demand in China to increase greatly consumption without having to rely on consumer debt. Simply putting in place an adequate social welfare system would go a long way to provide this. He has argued that this type of rebalancing could in fact ward off a hard landing and provide scope for a more sustainable economy. But he also notes that the longer this is put off, the harder any landing is likely to be.

I agree with the author that formation of bubbles is evident to anyone who really wants to look. Since the average guy does not have access to the media, it would take a very influential elite person (who is handsomely profiting from all of the debt creation) to step forward and start screaming from the rooftops, “Hey, everybody, this is getting out of hand, there’s too much private debt being taken on, and this is going to crash.” What are the odds of that happening when that very guy is profiting from it? Zero odds.

So now that I’ve milked this debt creation all the way up to the crisis, milked it all through the various QE’s, but I see now it’s evident that it’s all going to fall apart, NOW IS THE TIME for debt restructuring? Where were you crying out from the bleachers before this ever got to the crisis stage? Where were the elites? I’ll tell you where they were – they were too busy profiting.

“Debt relief in the form of restructuring or partial debt forgiveness should be seriously considered as an option. What if we were to let lenders write down underwater mortgages over an extended time frame (30 years)? While less necessary today, if this had been done in 2008, it would have made an enormous difference in the trajectory of the recovery.”

Here’s what should have been done in 2008: the banks, which were insolvent, should have gone bankrupt. They should have been nationalized, broken up into smaller pieces, and sold off. People who took on more than they could chew should have gone bankrupt. It’s what always used to happen. It works. That allows others who did not get into huge debt to come in and restart the engine, but at much lower prices. Because of this fear of bankruptcy, the new lenders will be much more wary about who they lend to. There must be consequences, otherwise the foolish are rewarded while the prudent are penalized.

Therein lies the problem: the elite who are in way over their heads don’t want their fake wealth to all go up in smoke. They want debt restructuring in order to prop up their assets (no way they want their asset prices to decline). In other words, they want the balloon to be continually inflated because otherwise they lose. That’s all QE did: allowed banks/corporations/institutions to borrow very cheaply in order to buy up assets and put a floor under them.

Bankruptcy was the answer in 2008, but because it didn’t benefit the elite, it didn’t get done.

One thing to consider is that the human population, going from 3 bn to 7+ bn is the reason that, in the 20 c., our “economy” (what a euphemism, no?) was such a juggernaut. Ha. Now we are faced with an inevitable confrontation: “sustainability” – and that means we have to stop our voracious, and insane, industrialism. For all the reasons we have all heard and blocked out. Oh god, you mean we are actually going to die someday? But this means we need to finally, after kicking and screaming, come to confession. Especially our egregious international corporations. The private debt that emerged was merely a political solution to keep those corporations alive by consumerism. But nobody knew why, what was the final goal? So here we are. The big internationals won’t say anything that damages “their bottom line.” A very fat bottom line indeed. And we are left to tell the privateers politely that what they are doing is not just killing us, but literally killing the planet….

Well, I think that once California starts exporting designer watermelons to Asia, Asians will forget about all their troubles and just be happy. You don’t need much else when you have watermelon to eat – you can even do it with chopsticks – no need to buy silverware and all that industrial production nastiness that would entail.

I do have a nit to pick with the design of chopsticks, however. I have learned to use the things, but they are horrendously inefficient for consuming Sweet and Sour soup. Where I get my chopstick skills is in an American-Chinese restaurant (or sometimes Japanese too) and they do provide these plastic sort of spoon shaped utensils. They are shaped just differently enough so that we may think they are Asian spoons, but then sometimes I think the restaurant is just messing with our heads and this was some American idea. The name of the restaurant is the Wok&Roll. Fishy sounding, I know.

But anyway, one time I was staring at my Sweet and Sour soup – listening to the usual slurping sounds from the diners around me – and I realized the chopsticks needed a hole, lengthwise thru the middle. Just insert the chopstick in the soup and use it like a straw! Sometimes I think back on this discovery and it makes me feel good that I thought of it and 3 billion Asians didn’t. Pretty impressive, huh? If I weren’t so lazy I’d get a patent on it.

But anyway. Back to the present. Sure we have this need to de-industrialize a world of 7 billion, and we may have to wait a little longer until economists tell us how, (tho I’m sure some will be quicker on the draw than others) but one step forward at a time. California Designer Watermelons. Hollow chopsticks. The rest will all fall into place as we go along.

The key, to consuming your soup with chopsticks, is that you have to pick up the bowl and bring it to your mouth.

That’s what they do in Asia.

Another idea people haven’t thought of is eating with 3 chopsticks, instead of two. I think you can eat more like that.

Actually, you pick the solids out of your soup first, using the chopsticks, then lay down the sticks, pick up the bowl delicately with both hands, and drink from it. A Buddhist taught me that.

Elderberry twigs have a soft pithy center I believe. A twig twice the width of a standard chopstick and just as straight could have the pith burned out from end to end with the equivalent of a very straight red-hot length of coat-hanger rod.

Or narrow bamboo stems would also be hollow and very strong. A red-hot length of wire just barely less wide then the hollow space inside the narrow bamboo stick could burn through all the septa (lateral

woody dividers that divide up the length of the bamboo stem into “bulkheads”.

“China may never undertake such systemic private-debt restructuring, but it is the surest path to revitalizing its beleaguered business sector, remedying overcapacity issues, stabilizing prices, and restoring reasonable growth. By alleviating rather than simply disguising China’s high private-debt-to-GDP problem, it would leave corporations in a much better position to lead renewed (and, hopefully this time, more measured) growth after the slowdown.”

Don’t you just have to laugh at the “hopefully this time, more measured growth” part? After alleviating their debt problem, the financial elite will suddenly have a “come to Jesus” moment and cut back on their debt? Ha ha ha! Like that’s going to happen. No, what the author really means is it would allow them to crank their debts back up (does a shark act differently just because he’s in different waters?), get inflation going again, ramp up growth (like the Earth needs more!), and their profits can continue to climb.

Reading his piece, I could see his wheels turning. He really wants “something for nothing”. He and others have created a shitload of harm and now want to get out of it with as few cuts and bruises as possible. The Federal Reserve and the government have been bailing out and aiding the likes of him for the past 30 years. The market would have pounded his head into the sand. These guys don’t want to suffer consequences. That’s not how they roll. They want to be bailed out again. Financial and corporate welfare for the elite. It’s all couched in terms like, “Oh, it will help the average person,” like they could give a shit about the average person.

Anne Stevenson-Yang on China: 4:00 minute mark to 28:00 minutes. She believes shadow banking is about 55% of funding, although some think it is much higher.

“Nobody really has a good grip on who owns all that debt. So allowing debt instruments to go belly up can create this chain of consequences that any government would be terrified to be confronted with. Therefore, you keep everything rolling over. Right now the amount of capital that’s required to keep it rolling over has reached a dangerous level. We’re putting about 1.2 trillion renmimbi into the system every day just to keep the banks liquid, and that creates all sorts of opportunities for failure.”

1.2 trillion renmimbi into the system EVERY SINGLE DAY! That’s U.S. $192 billion per day. Debts are just continually being rolled over to keep the system going and to save the elite from swinging. Corrupt money is fleeing for the U.S., Australia, Canada. The elite have raped and polluted their own country and are now running with their ill-gotten gains.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C2SStFt-k_A

Thank you for the excellent link, backwardsevolution. Appears the headline to this post should be in the present tense.

Since I don’t have my own economic model, I can only go by common sense. Large parts of the economy, and much of the 10% who feed the .01% depend on debt for their own livelihoods and to keep their jobs.

They can’t simply run a company that makes a profit, they have to show constant growth. And they can’t do that without borrowed money. If we had a rational economy, much of the %10 would be out of a job.

The latest Doonesbury reprints about spraying to reduce the infestation of “preppies” might also have something to do with it. If there are no productive careers open to them, once the number of preppies exceeds some bottom-line number you need increased debt and increased rent-seeking to support them.

Excess Private Debt resulting from bad loans and investments resulted in the 1929 Depression, Japan’s Lost Decade, and the 2008 Great Recession. Time and growth resolved previous depressions. The innate human condition described by John Kenneth Galbraith still prevails; “People of privilege will always risk their complete destruction rather than surrender any material part of their advantage.” As a result, Cold War 2.0 is off and running. Greece is pillaged. America is a teetering House of Cards with demand bottlenecks caused by climate change, resource depletion and lowering wages. China with one party rule may indeed be able to write off the bad debt. Their wealthy will scurry off to safe havens bearing diamonds and Ming vases in the Carry-ons. Or, instead, the Chinese communist government has been bought by the rich just like the West. If that is the case, we are living in a Lost World.

I scanned and then read this post. I don’t have a warm feeling for its projections nor for its reasoning. Though this may strike some as verging on insane, I started to long for some sort of equations to express the models behind many of the author’s assertions. I left the article with a strong feeling of discomfort about the future of China’s economy and by its connection with our economy a bad feeling in my stomach about the future of our economy. Then again I’ve felt uncomfortable and pessimistic about our economy for a long time. I should still be in hibernation.

There’s an old saying — if something seems too good to be true, it probably is. The saying tells us to trust our nose. My nose, a relatively large and long nose, tells me China’s growth is too good to be true. I’ve felt that way for a long time though. My nose also tells me that my bear feelings move through time too quickly. A lot of money can be made waiting for the moment J.P. Morgan characterized as — step away from the market and “leave a little for the next guy.” Advice not to hold-em too long. Right now my nose is twitching telling me, though I’m not invested in the market, now is the time, the time really, really, to sell and walk away.

I must declaim my views based on their past successes. But this time … this time is different, my feelings of a “gathering storm” afflicting China’s economy and impacting world economies are becoming downright epileptic. Based on my past successes — NOT!, I guess it’s time to invest in China?

I am having troubles with the comments programming. The widget for URL — website has disappeared from my browser. I have been editing my comments to add the website after the fact — “Name” “Email” “Website”. My most recent comment appears to have been accepted immediately after I made an edit without editing the entry for website. The comment above, shown as “undefined” is mine — Jeremy Grimm. I own what I say and will defend it, speaking neither lightly, nor frivolously, nor without honor and responsibility.

I use Linux 10.4 on an older 64-bit system with Firefox. I installed the ghost pluggin and set it to block everything a couple of days ago. When I saw problems, I opened ghost to all links widgets and all, but that had no effect. I tried combinations of blocking with no effect. Please advise. I would open ghost if you, Naked Capitalism, might profit through the multitude links enabled. I closed ghost down because the delays in filling the links had reached a point where I was unable to move around as I browsed.

We have eliminated the URL line entirely. It has not been visible to readers since our redesign and hence does you no good in terms of Google points. However:

1. Having a URL line is very appealing to spammers, who assume it DOES appear and

2. More important, URLs in comments that post (as opposed to go into spam) have been wreaking havoc with the site. It makes no logical sense to anyone, but they can and do crash the site and it reclogs up within minutes of a reboot. The only way to fix the problem is for me to manually delete the URL line on all comments that appeared immediately prior to the crash. Each time this has happened recent, it has taken 1-2 hours of my time in the middle of the night with my webhost on the line, since the site keeps crashing and thus needs to be rebooted again and again till the cleanup is complete. I don’t have time like this to waste, particularly on a now vestigial feature.

tl;dr: Please don’t game the fields by adding URLs where there’s no reason for them to be. Otherwise, Yves will have to spend hours and hours cleaning them out when the site goes down after some mysterious entities discover the URLs’ presence and slows the site down.

I think its far worse than financial. I think Yves has covered this but I will mention it again. Its the pollution food water and land and especially the air which is toxic. I think its very possible most people in China have in a very real sense died and I wonder if that explains some of the very strange things we seem to be seeing in the leadership there ,the commodity collapse and so on. I have been following the Chinese air data for a couple of years and its bad over a vast area and its been bad for 10-20 years or more. Even though it gets coverage I think that coverage has missed how dire it may have already been. I look at this website daily . There are some plus 700 pm 2.5s today. Area we at Peak China?

http://aqicn.org/map/

Private debt can be good when overall levels in a country are low or moderate, and when, for example, it is used to finance projects whose income can repay that debt. The problems come when private-debt growth is too rapid or reaches levels that are too high.

. . .

Why does runaway growth in private debt lead to financial crisis? First, because it means that far too much of something has been built or produced.

Isn’t building dozens of empty cities pretty well the definition of “far too much of something” So the real problem is that none of this investment is actually viable, because of “finance projects whose income can’t repay that debt.”

The only reason the “private sector” can take on more debt is because governments lowered interest rates, after Volker’s punishing high interest rates to “stamp out inflation”.

It took a while, but it worked. Now we’re below zero.

Overcapacity is the flip side of a lack of aggregate demand. Once capacity outstrips our ability to consume, should we not stop? I’m sorry, but I cannot see the point of having a government spend money into existence to relieve a lack of aggregate demand: we cannot use more ships (even if there is a ship output gap) and the environment cannot cope with more abuse.

One surefire way to reduce private debt is to allow the lenders to go bankrupt. If there is no lender, I assume the borrower is freed of debt and also is suddenly asset rich.

Couple of goods things would arise. The assets will be repriced, lenders will know how to price risk and lend prudently and you will get growth, after a massive upheaval.

Not gonna happen. So keep dragging like Japan. In a while you will see the world consists of only Japans.

Save Banks, Screw Tax-payers, Forget growth!

I guess supply does NOT create demand..sheesh who knew ?