Yves here. Tverberg argues that low oil prices likely to be with us for a long time, due to the fact that demand will remain relatively weak. Given the reluctance of governments to engage in aggressive enough spending measures, the idea of that more economies will become mired in a Japan-like slump or weak demand is entirely plausible. And that’s before you get to the wild card of a Eurozone unraveling.

By Gail Tverberg, an actuary interested in finite world issues – oil depletion, natural gas depletion, water shortages, and climate change. Originally published at Our Finite World

For a long time, there has been a belief that the decline in oil supply will come by way of high oil prices. Demand will exceed supply. It seems to me that this view is backward–the decline in supply will come through low oil prices.

The oil glut we are experiencing now reflects a worldwide affordability crisis. Because of a lack of affordability, demand is depressed. This lack of demand keeps prices low–below the cost of production for many producers. If the affordability issue cannot be fixed, it threatens to bring down the system by discouraging investment in oil production.

This lack of affordability is affecting far more than oil products. A recent article in The Economist talks about LNG prices being depressed. LNG capacity ramped up quickly in response to high prices a few years ago. Now there is a glut of LNG capacity, and prices are far below the cost of extraction and shipping for many LNG suppliers. At least temporary contraction seems likely in this sector.

If we look at World Bank Commodity Price data, we find that between 2011 and 2014, the inflation-adjusted price of Australian coal decreased by 41%. In the same period, the inflation-adjusted price of rubber is down 58%, and of iron ore is down 59%. With those types of price drops, we can expect huge cutbacks on production of many types of goods.

How Does this Lack of Affordability Come About?

The issue we are up against is diminishing returns. Diminishing returns mean that as we reach limits, it takes increased resources (usually both physical resources and human labor) to produce some type of product. Oil is product subject to diminishing returns. Metals of many kinds also are becoming increasingly expensive to extract. In many parts of the world, a shortage of water makes it necessary to use unusual techniques (desalination or long distance pipelines) to obtain adequate supply. The higher cost of pollution control can have a similar effect to diminishing returns on products with pollution issues.

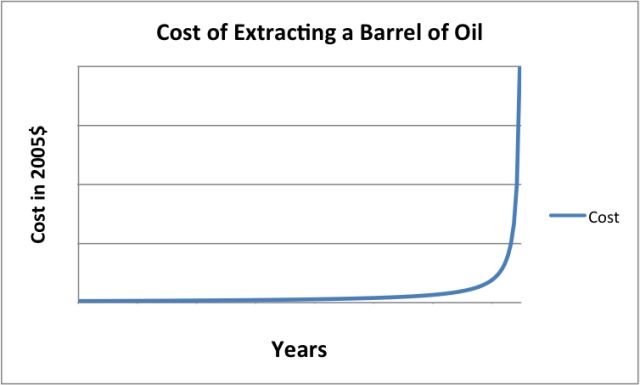

When we graph of the cost of production of resources subject to diminishing reserves, the result is similar to that shown in Figure 1.

What happens with diminishing returns is that cost increases tend to be quite small for a very long time, but then suddenly “turn a corner.” With oil, the shift to higher costs comes as we move from “conventional” oil to “unconventional” oil. With metals, the shift comes as high quality ores become depleted, and we need to move to mines that require moving a great deal more dirt to extract the same quantity of a given metal. With water, such a steep rise in diminishing returns comes when wells no longer provide a sufficient quantity of water, and we must go to extraordinary measures, such as desalination, to obtain water.

During the time when cost increases from diminishing returns were quite minor, it generally was possible to compensate for the small cost increases with technological improvements and efficiency gains elsewhere in the system. Thus, even though there was a small amount of diminishing returns going on, they could be hidden within the overall system.

Once the effect of diminishing returns becomes greater (as it has since about 2000), it becomes much harder to hide cost increases. The cost of finished products of many kinds (for example, food, gasoline, houses, and automobiles) starts rising, relative to the income of workers. Workers find that they must cut back on discretionary expenditures in order to have enough money to cover all of their expenses.

How Diminishing Returns Affect the Economy

There are at least three ways that diminishing returns adversely affects the economy:

- Lower wages

- Less ability to borrow

- Squeezing out other sectors of the economy

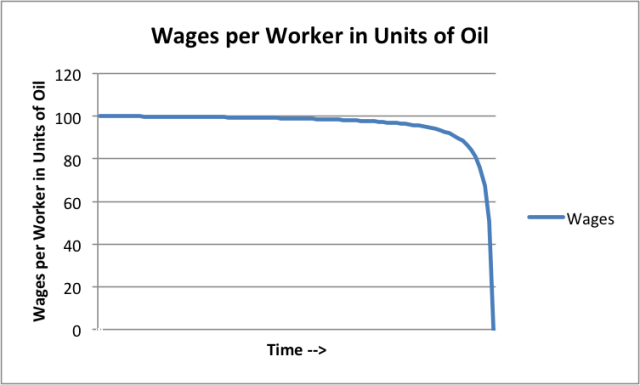

The reason for lower wages relates to the fact that, as the cost of producing a commodity rises, the worker is, in some sense, becoming less and less productive. For example, if we calculate wages per worker in units of oil, as oil becomes more expensive to extract, we get something like this:

A similar chart would hold for other resources that are becoming more difficult to extract, or whose cost of production is becoming higher because of greater pollution controls. For example, we would expect the wages of coal workers to be falling as well.

Also, as we shift to higher cost types of energy, we become increasingly inefficient in energy production. Based on a 2013 analysis, in the United States, there are more solar energy workers than coal miners, even though we use far more coal than solar energy. The large number of workers required to produce solar energy is one of the reason that solar energy tends to be high-priced to produce.

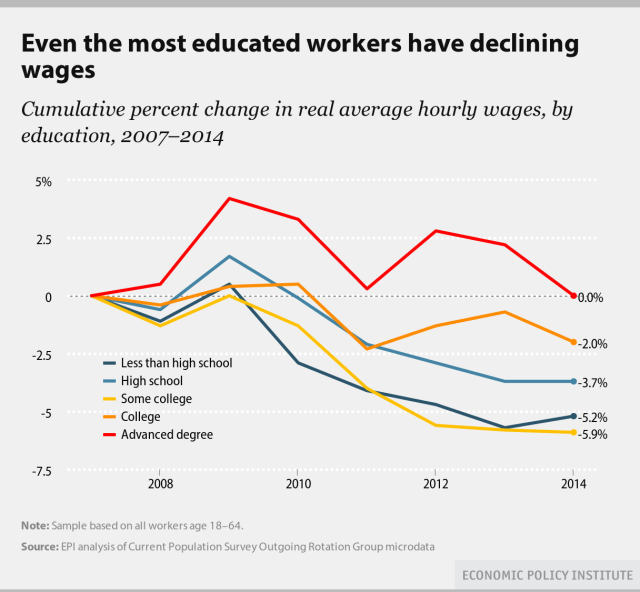

When we look at wages of workers, we indeed see a pattern of falling wages, especially for workers below the median wage. Figure 3 from the Economic Policy Institute shows that even the most educated workers are experiencing declining inflation-adjusted wages.

A second major issue affecting affordability is debt saturation. Affordability is favorably affected by rising debt–for example, it is a lot easier to buy a new car or house, if the would-be purchaser can obtain a new loan. If debt levels stay the same or fall, this becomes a problem–fewer goods can be purchased.

Governments in particular are reaching the limits of their borrowing capacity. They cannot keep adding new debt, and remain within historic debt to GDP ratios.

Another way debt saturation occurs relates to young people with student loans. They find it too expensive to borrow more money for a new car or for a home. Furthermore, the fact that wages are not keeping up with price increases for many workers reduces the borrowing ability of the workers with lagging wages. This is true, even if no student loans are involved.

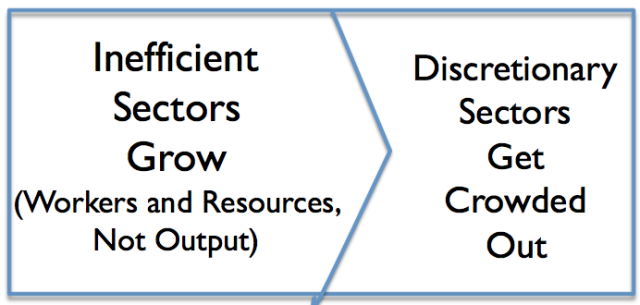

As mentioned above, a third issue is the fact that the inefficient sectors tend to squeeze out other portions of the economy by gobbling up a disproportionate share of workers and resources. The use of all of these resources doesn’t produce a lot of goods in the traditional sense–a desalination plant is expensive, but the amount of water produced per dollar of investment is not large. To the extent that the high costs of inefficient sectors are passed on to consumers, consumers find that they must cut back on discretionary spending. This cut-back in spending squeezes out discretionary spending, leading to cutbacks in discretionary sectors, and to reduced employment overall.

Wishful Thinking by Economists

Back before diminishing returns started becoming a major problem, economists created models regarding how the economy would react to higher cost of energy production and other symptoms of diminishing returns. In their view, if the cost of oil extraction rises, oil prices will rise to match these higher costs. Alternatively, substitution will take place, or technological changes will allow greater efficiency, or customers will cut back on their use of the high cost product. Somehow, these changes will take place without a particularly adverse impact on the economy.

Unfortunately, the models don’t correspond very well to what happens in practice–at least not for very long. It takes inexpensive energy to produce goods that workers can afford. Higher priced energy does not work well in this regard. Feedbacks that are not reflected in economic models reduce both wages and debt, making it harder to buy goods requiring the use of more-expensive energy products.

Furthermore, if the price of one commodity, for example oil, rises, then countries with very much oil in their energy mix find themselves handicapped in trade with other countries that use less oil in their energy mix. For example, a country that depends on tourism (which depends on oil use) for very much of its revenue, such as Greece, finds it difficult to find customers when oil prices are high. Lack of revenue can lead to financial problems for the country.

Because of the networked way the economy really works, prices for commodities can’t rise for the long-term. They may rise for a while, as consumers and governments borrow more, in an attempt to continue business as usual. Ultimately, though, the situation can’t “work.” Customers can’t afford to buy more homes and cars, unless their own wages are rising in inflation adjusted terms, and governments can’t collect enough tax revenue.

The issue we are dealing with here is lack of affordability. This is what will bring the system down–not the high priced scenario imagined by many. Decline will come through low prices, and a glut in oil supply, even if we are not looking for it from that direction.

Can Commodity Prices Rise Again?

It is not all that clear that they can rise again. It would be a lot easier for commodity prices to rise, if the problem were simply inadequate prices of one commodity, leading to a lack of that commodity. If the problem is inadequate demand for crude oil, coal, LNG, and iron ore the problem is much greater–especially if wages are still lagging.

This is the magic of QE and ZIRP for the elite. The vast amounts of liquidity created allows them to borrow money even when the enterprises they command can’t make any money. You suppress wages to boost profits while borrowing money to cover losses. All that matters is milking the cash cows until they dry up then jumping ship before the cow dies. You get rich and leave behind–nothing. It’s a kind of economic scorched earth policy for the Power Elite going into the period of oil, water, and soil shortage which lies ahead. This is literally, to keep with the cow metaphor, the last roundup before industrial civilization lurches into reverse. They’re hoping to take enough of the weapons, surveillance equipment, and money into the collapse to cushion the fall (for them). This has got to be their conscious or unconscious strategy, as they are doing nothing to prevent the disasters that loom. Of course, they could all be venal, short-sighted, and stupid, but I doubt that could be true of all of them.

Indeed, they will kill all the Kennies… bastards!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y1vkyb8ioWg

Yes, indeed. They are preparing their Galt’s Gulches. If if IF! we cannot derail or stop the process, can we at least find a way to throw bubonic plague corpses over every gated wall around every Galt’s Gulch?

Actually, the wealthy are planning to upload their consciousness to immortal machines and set off to explore the cosmos.

If affordability means ‘lack of money’ as suggested in the article, then there is clearly a solution given that one thing we can produce ad infinitum is money. To my mind the author misses the real issue, which is resource limits. The focus should be on using our infinite supply of money to make ‘affordable’ a switch to sustainable modes of production.

Fully agreed. The problem is having a process to get there that minimizes human and “Gea” suffering, while working in the sort of decentralized decision making system we have now. Not easy, I think.

“using our infinite supply of money to make ‘affordable’ a switch to sustainable modes of production”

Oh, the fallacy! Money is just a unit of account. Print ten times more, prices go up by a factor of ten. But the productive capacity of the economy, and affordability of goods, remains exactly the same.

Believing that value can be created ex nihilo with more units of account that cost nothing to create is an economic version of a perpetual motion machine.

You know that’s not true. The money supply has been increased by several hundred percent, but prices have not risen several hundred percent. If the money doesn’t circulate, if it stays in the hands of the wealthy, it doesn’t drive up prices. Money has to be in a position to bid up prices before prices can rise, which I think is part of the point of this article.

> Mischaracterization of perpetual motion machine

Explain that again in the context of 10% real unemployment and staggering resource underutilization. If we put more money in circulation we will indeed create more value.

> But the productive capacity of the economy, and affordability of goods, remains exactly the same.

As we should all know by now, labor does not have the bargaining power to ensure goods stay affordable.

Furthermore, the longer we let people rot in unemployment and productive capacity sit around unused the more we destroy the capacity of our economy.

Sounds like the problem that Michael Hudson is constantly referring too, debt deflation. In developed nations individuals have been saddled with so much debt (for healthcare, for housing, for education) that whatever wage increases they garner, they cannot consume more. Ultimately guns have won out over butter and labor unions have lost so much clout that wages across the world have not risen along with GDP and productivity gains.

Oil is low because it assists US foreign policy goals (maintaining hegemony, managing decline). It will stay low until Vladimir Putin departs with plausible deniability for US power ministries. The end. Then oil will spend a long time above its prior $100 per barrel norm. This is a political question, not an economics question.

I think this assessment makes the stronger case…agreed, Ben Around.

The price isn’t low, it just had a significant change.. all about Delta $.

Last time it was around $50-52 /bbl BP Exxon etc were planning normal capEx… business as usual

The evidence is MUCH stronger that this move was to undercut US frackers and throw a wrench in plans to start building LNG facilities for export (they’d actually likely be uneconomical, since US fracking future production is greatly exaggerated, we’ve posted on that, so the Saudi strategy might not merely delay the building of LNG transport facilities but kill it as the word gets out about the geological work that is not Wall Street boosters amplifying fracking companies that need continued access to cheap funding).

See this, for instance, on the latest remarks by the Saudi oil minister:

If al-Naimi is right, then his strategy was correct, and it acted quickly. It was only three months ago at OPEC’s headquarters in Vienna that the Saudi minister pushed through a plan to maintain oil production at 30 million barrels a day, declaring a price war with US shale oil producers who rely on costly hydraulic fracturing, or fracking, to extract oil embedded tightly in underground rock.

The US shale producers had not only created a global oil glut, which was depressing the price of oil, but they also had turned their country from OPEC’s biggest customer to a nation headed towards energy independence.

http://oilprice.com/Energy/Energy-General/OPECs-Strategy-Is-Working-Claims-Saudi-Oil-Minister.html

The “energy independence” is also a canard, since it is based on overly high estimates of how much shale gas the US has, but on a near term (5-12 year time frame) it was still a problem for the Saudis.

The Saudis have been unhappy with the US politically for several years. They are very upset that we did not attack Syria and have failed to attack Iran (the latter would be madness, this is one of the rare cases where even the crazy neocons have exercised some restraint). While they would see hurting Russia as a plus, since Russia is an ally of Syria and Iran, they aren’t going to hurt their revenues to advance US geopolitical aims, which is what the “Saudis did this to hurt Russia” logic implies. The Saudis are independent actors as far as how they use their oil weapon is concerned.

It’s not very popular and all, but I seem to recall a certain German who foresaw this over a hundred years prior (I seem to recall him referring to it as economic law, or some such.) In fact, the idea that inevitably profits fall was such a powerful theory that most mainstream economists accepted it as fact until fairly recently.

Not to be a troll, but seriously, this was all laid out a really long time ago. Parse it all you want, but you might want to go back to the originals who happily explained exactly how this works. It’s just basic economics with any industry. But it also wouldn’t be playing into that “running out of everything” doom-porn that everyone is enjoying here, all while leaving unremarked in this context that the rich are certainly not “running out of everything”… I swear, sometimes it’s like people think history started in 1913.

Surprising that Gail doesn’t mention demographics.

Old people don’t drive much, and as the ratio of working to non working people keeps drifting lower, demand goes down, and not just for oil.

There is also a growing number of people making a conscious decision to arrange their lives with the concept of reduced consumption as a goal. Going from two cars to one or none. Moving away from far flung suburbs where a car is a neccesity to an urban area and a smaller place to live.

When I look at what teenagers and young adults have as a priority, messing with cars is not even on the list, unless it’s in a video game. Besides, the new cars are untoutchable by their owners. BMW has even taken away the dipstick, and after reading my neighbor’s Roundel magazines, a source of aggravation to BMW enthusiasts.

Demand for oil from speculators drove the price high enough to send false signals of demand to the oil patch. The Fed is directly responsible for that, with ZIRP.

Declining wages are the deflationary result of globalization. More and more workers are subjected to competition from, what is in essence, slavery. Chinese workers make a minute fraction of what even a Walmart shelf stocker makes here. When Apple has their products made by the Chinese, the difference in expenses if production were in North America, is captured by Apple executives.

Those declining wages by workers here drag down the wages of the most educated workers, simply because, where is the money to pay for a $1000 per hour lawyer or doctor?

Having oil go to nearly $150 per barrel just before the GFC (Great Financial Crime) scared many people. During that period, I was able to ride a bicycle mostly, and burned one tank of fuel, for the whole summer.

Simple cures:

Set a minimum LIVING wage and also set a MAXIMUM wage (for executives). In addition or instead, set the min wage and then restructure corporate tax law so that corporate taxes are lowest when a company pays it highest compensated executive no more than 60x the average wage of workers in that company (in actual US dollars – no skating on trying to use “equivalents”, ie, $1000/yr for worker in backwoods 3rd world nation is “equivalent” to a salary of $30k in the US. No, you pay someone $1000/yr then your max comp for the top exec is 60×1000. Period). They are free to pay their top exec(s) more than 60x the average worker wage in their company but corporate taxes will increase accordingly. There. Fixed both income inequality and loss of affordability by real people (workers). I’ve saved the economy and the people. You’re welcome.

Better still tax corporations based on how much tax their employees pay, ie higher wages less corporate tax

Simpler. Anything over a $million per year income per executive is not a tax deductible expense for the company.

@cnchal, Larry, Nell (so far) –

Superb comments in addition to the article. But if we are fkcued so many ways from Sunday – demographics, resource limits, guns & butter, changing values – where does this lead and how will we deal with it? So many issues seem to be coming to a head all at the same time it boggles the mind.

Of course the Dear Leaders in every country will likely make all of the wrong choices when determining what should be done…..

Is there any palatable fix or will it just continue to play out > until it cannot go on for one more minute? I do feel like I’m riding a carnival ride with a crazed madman who is pulling the lever ever harder until the mechanism fails and it just breaks off in his hand.

The latter. It is always the latter (keep playing it out until it can’t play any longer no matter what). True for the economy, same for resources, same for “dealing” with global warming.

Hasn’t Warren Mosler been arguing that the decline in oil prices is solely due to OPEC (particularly Saudi Arabia) deciding to lower the price asked to decrease market share for other producers?

I seem to recall back in those peak Hope days that low oil prices would have been all the more reason for stimulus spending on infrastructure such as finally laying fiber internet to every home already on the old phone or current electric grid, solar panel on every south facing roof, repairing/replacing bridges, establish high speed rail, etc.

But I have read in puzzlement for a year now everyone moaning about the perils of cheap oil. Even on fine blogs like this where a wink and a nod are given with sincerity to the 90 percent. We need to seize the day. Seize the opportunity this, what could be the last ‘cheap’ oil days (especially if it lasts a couple years) we ever have…. and make sure we are less dependent than ever when the tables turn.

Demand = sales

Sales higher if people have more money

People have more money if deficit higher

high deficit no problem if more people employed;

Remember wwii and its highest ever deficits… Who now worries about those record deficits?

So… Falling commodity demand mostly a Chinese tale, with a dash of austirity induced unemployment. The long predicted commodity shortage no doubt coming, but not here yet.

The line: “there are more solar energy workers than coal miners, even though we use far more coal than solar energy.” seems to be comparing apples and oranges to me. Most of the solar jobs are for installation. Most of the coal jobs are extracting coal, a hazardous activity. I doubt she was factoring in the workers at the coal power plants. Of course, once the solar cells are installed they are pretty low maintenance. If you stop extracting coal, the coal plants stop generating electricity. A better measure would be hours of labor per kilowatt hour generated over the life of the installation if we only care about the direct human costs and measuring whether solar is more inefficient than coal. Factor in the environmental costs and solar does even better.

i agree that oil looks set to remain low for a while (i’ll ignore other commodities for now). however, as prices stay low or drive lower, producers will start pulling out of the market, and we haven’t seen too much of that yet. markets have a tendency to over-correct so, once enough producers pull out, there will be a demand shortage which will cause prices to rise in another boom.

i think a boom-bust cycle awaits us and not perpetually declining prices.

I have a huge respect for Gail Tverberg’s work in general, but this is one area where I just disagree.

There seems to be a good point buried somewhere in here. First, Jim Haygood makes an excellent point (and Jim Levy seemed to be making much the same point) is that “money” is just a unit of accounting and what is important is what happens with real resources. The financial system may or may not match up units of money with units of real resources. When oil takes more resources to extract, which is what the peak oil theory predicted and which is what seems to be happening, then the resources are taken from the wider economy and everyone gets poorer.

Particularly if the link between money and real resources is broken, then “the wider economy getting poorer” can show itself in terms of prices in different ways. It could be oil and everything going up in price. Or it could be the price of oil staying the same or dropping and wages dropping instead. You could also having cheap oil in money terms that is just not that available under some systems. You could have nearly everyone get a little less of everything, or most people having a lot less and a few people having more then they could handle.

The point is that if oil takes more resources to extract, it will have to work its way through in terms of reduced availability of oil, higher prices for oil, reduced availability or higher prices for eveything else, or I guess just cutting everyone’s wages so that it takes more hours of work to get the gas needed to go to work can happen too.

However, I suspect the current drop in oil prices is a power play to take down some regimes being targeted by the US and Saudi governments and won’t last long. I don’t think you really need to spend much time analyzing this. Also when planners start setting prices instead of the market you will be bound to get inefficiencies where the prices no longer reflect real resource constraints.

I’ve read here and there a Russian analysis that suggested the oil price drop was a US-driven push to try and force economic problems on Russia, with the idea that this would cause the Russian people to turn on Putin and oust him. The analysis went on to say they thought that the US could swallow the damage from low prices for around 6 months before their ability to absorb it came to an end (and that Russia could easily outlast the US on this matter). Other analyses thought it is Saudi Arabia trying to kill off US competition (the frackers) before theycould then start cutting overproduction. They also were seeking to hurt Iran (and the US being OK with this because of the side effects of harming Iran and Russia, ergo Putin). The final analysis remains that the US can handle the hurt itself for around 6 months before it needs to get prices up to more “normal”.

The last time I read commentary by Gail , it was on the Oil Drum, a blog devoted to ‘peak oil’, that is , we have seen an absolute peak in available/economically recoverable fossil fuels.

The ‘Oil Drum’ is dead, overtaken by events that contradicted it’s basic premise.

Accept the fact that fracking has made tremendous amounts of fossil fuels accessible. As the learning curve develops – like any technology – prices of fracked fossil fuels will fall. This is not the whole story, but the great bulk of why fossil fuel prices have fallen. Like it or not, the energy industry was right . The boom/bust cycle has happened repeatedly in energy – and has happened again.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uwGz4foNsx8

From 4:15 to 6:05

Ugh. Pickens is the worst spokesperson for peak oil. Conventional crude oil production peaked in 2005. The only growth that has occurred in crude oil has been as a result of tar sands and tight oil and even then crude oil production has grown less than 1% per year in that time. And that’s with higher prices and much more CAPEX. Between 1998 and 2005, industry spent $1.5 trillion to grow global production by 8.6 million barrels a day. Between 2005 and 2013, they spent $4 trillion to grow production by 3 million barrels a day.

No arguments from me there ….because we think alike on this point.

But I think Pickens-the-republican-oil-tycoon is quite suitable to add to the chorus of peak oil “advocates”. Plus, I just love posting this segment as link because of the way that baffoon of an anchor just enters into convulsions as he utters the “Malthusian argument can’t be real” line….lol

People just can’t handle the truth. It took me some time to understand just how much people are uncomfortable about this topic. Even highly educated people can be caught going out of their way to dismiss the mere possibility that the old [inescapable] principle might still hold true.

Malthus might have been an elitist clergyman (although that sounds a little silly), he may have gotten his forecast wrong (because of fossil fuels) — but to date, the principle still holds.

Absent a deus ex machina physics breakthrough (and I mean the completly out there Star-Treky cheat thingy); nothing, nothing warrants optimism on this issue.

Gail is one of the few people that realize that oil, and the energy it represents, generates the economy. Given the fundamental role of energy in the world, it has become far too expensive. Put another way, the total expense for energy in the world today has broken the relationship that grew the economy to where it is today. It is consuming society, where it used to generate society.

Humans are very resourceful at finding energy to power all their toys, but we are bad accountants at seeing what the cost of the energy complex really is. And expense is always relative, more proportional than fixed. We have hit the death cross with energy. The relationship with energy that generated more growth as we found more energy has flipped. We have all seen the graphs of net growth for additional borrowing, and oddly enough they have gone negative too.

Negative returns, for more energy, for more credit. The western model for growth is officially dead.

Given the reluctance of governments to engage in aggressive enough spending measures, the idea of that more economies will become mired in a Japan-like slump or weak demand is entirely plausible. And that’s before you get to the wild card of a Eurozone unraveling.

There is a broader point actually. That when you have a secular demand deficit, with at best anaemic growth, any shocks – which do happen from time to time – will send the economy into a recession which will be hard to escape because of liquidity trap issues. The Eurozone is just the crisis du jour.

So while the Eurozone unraveling may be a wild card, the fact that we will have occasional demand shocks of some kind is practically assured. We can expect a mixture of weak growth mixed with recession going forward; the current US economy is probably about as good as it gets.