Yves here. Offshore banking and tax haven expert Nicholas Shaxson has launched a new blog, Fools’ Gold, to look at issues of ‘competitiveness’ and so-called ‘competition’ between nations. We’ve often taken issue with that policy goal, since it gives precedence to crushing labor as a way of lowering product prices to stoke exports. This approach is dubious for anything other than small economies, since all countries cannot be net exporters. Undue focus on exports as a driver of growth results in increasing international friction, such as the currency wars that are underway now. Moreover, as we have discussed separately, trade liberalization has gone hand in hand with liberalization of capital flows, in no small measure due to US efforts to make the world safe for what were then US investment banks. Yet Carmen Reinhardt and Ken Rogoff pointed out in their study of financial crises, higher levels of international capital flows are associated with more frequent and severe financial crises.

In addition, lowering wage rates reduces domestic demand. In countries like the US, where the domestic economy is much larger than the export sector, lowering internal demand to stoke exports is misguided.

By Nicholas Shaxson, the author of Treasure Islands, an award-winning book about tax havens. Originally published at Fools’ Gold

Ireland has long been a poster child for corporate tax-cutting. The standard argument goes something like this. “Ireland has very low corporate taxes . . . Celtic Tiger . . . just goes to show that corporate tax cuts grow your economy.” This argument is popular in Ireland too where government officials like to call the flagship 12.5 percent corporate income tax rate a “cornerstone” of industrial policy.

But is any of this even true?

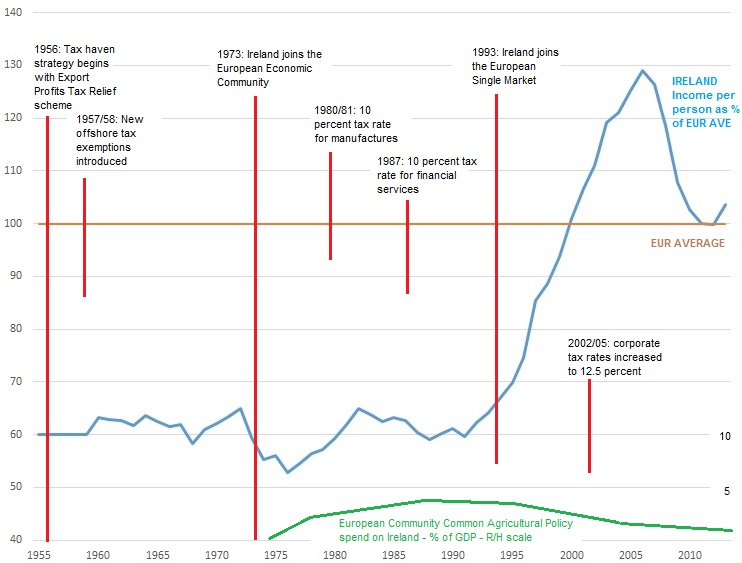

Well, now take a look at this little graph.

Chart 1: Ireland’s GNP per capita, relative to European GNP per capita, 1955-2013.

That’s a pretty clear picture of the so-called Celtic Tiger, now battered and bruised.

The graph casts serious doubt on the official story that multinationals and big accounting firms are desperate for people to believe (because this story is their meal ticket). The story is that Ireland’s low corporate income tax rate was a ‘cornerstone’ of Celtic Tiger-related economic growth.

Many people in Ireland and elsewhere have stopped even questioning the proposition that corporate tax cuts spur growth. But from first principles, it isn’t obvious why this should be so. A corporate tax is not a cost to an economy, but effectively a transfer within it*, shifting goodies to multinationals and their shareholders in the short term, at the long-term cost of fewer courts to enforce their contracts, or schools or roads or sewers. It is not obvious how this transfer necessarily spurs long term growth or makes an economy more or less ‘competitive’ (whatever that c-word may mean.)

So: what does the graph tell us?

Well, something happened in the early 1990s, when a huge surge began.

The inflection point came around the time of Ireland’s accession to the European Single Market in 1993. No geopolitical or domestic event or policy measure around that time came close to matching the importance of that. Note that the 12.5 percent tax rate was introduced long after the surge, and the 10 percent rate was phased in many years earlier.

The graph also shows how Ireland has been trying to be a corporate tax haven since 1956, but for decades it just did not seem to be working. Its relative economic performance basically flatlined until the mid 1990s.

Does our graph prove that Ireland’s 12.5 percent corporate tax rate doesn’t matter for Ireland? No: it could be that a tax haven policy only works in the context of an EU single market, of course.

So let’s try and see if this is the story. This next chart provides more context.

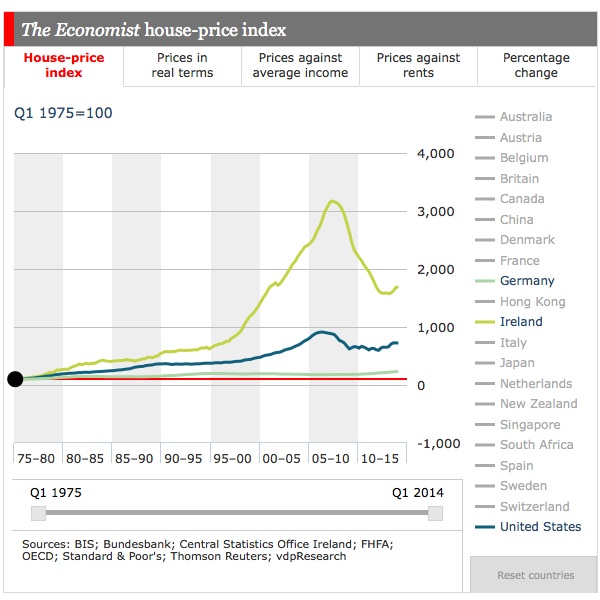

Chart 2: house prices, Ireland, Germany, United States

Now will you look at that yellowy-green Irish line, and how closely it resembles our graph at the top, timing-wise. That is a monster housing bubble, pricked by the financial crisis.

House prices are closely correlated with consumption. If your house doubles in value, you feel richer and you spend more. Consumption is a key component of GNP (and GDP). And joining the European Single Market clearly made a huge difference to what happened in Ireland’s housing market, as conditions changed, allowing Irish people to borrow freely and join the party. As Barry Eichengreen notes:

“Claims on the Irish banking system peaked at some 400 per cent of GDP . . . this was an exceptionally large, highly leveraged banking system atop a small island. It grew out of the high mobility of financial capital within the single market. It reflected [among other things] the freedom with which Irish banks were permitted to establish and acquire subsidiaries in other EU countries.”

Here we have the single market again, and the Eurozone, behind the surge.

But that is not all. Look at our top chart again, and consider what might have caused that possible mini-surge in the mid to late 1970s. Was it a dead cat bounce? Reversion to the mean?

Well, the timing again may point to Europe: specifically, to Ireland’s accession to the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1973. And was this it? Well, here’s Prof. Frank Barry from University College, Dublin, in a paper about Ireland’s economic development:

“Within manufacturing, EU entry brought a further substantial increase in employment in foreign-owned industry, with the number of jobs in this sector expanding by almost 40 percent between 1973 and 1980. This was to be expected as a consequence of the integration of a relatively low wage economy into the large EU market.”

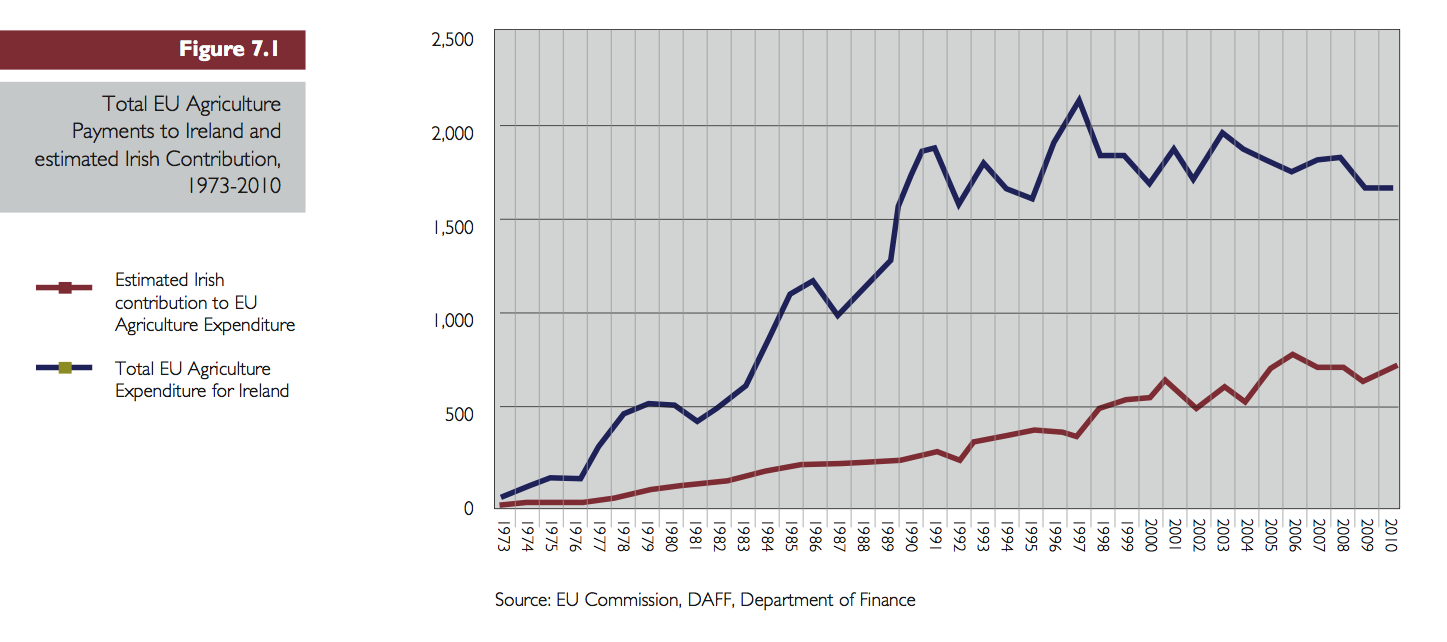

We also need to factor in all those lovely subsidies to Irish agriculture, which you can see in the lower green line in our top chart, and in more detail here below.

Europe again, at the heart of the story. And those are some hefty subsidies by Irish standards, rising to an average net 1.3 billion Euros-equivalent annually by the early 1990s on the evidence of this graph. (Equivalent-sized net transfers for the UK and US would come to over 15 billion and 120 billion Euros annually, respectively). And in this data we haven’t even included all those other European Development Funds (click on that link to look at the scale and diversity of the European funds Ireland has been tapping.)

In short, truly whopping transfers for Ireland. Yet the PR machine of the Irish tax haven and for corporate tax-cutters rarely cite these factors. Why would that be?

Have Low Corporate Taxes Attracted Investment?

These graphs don’t tell us, however, whether or not the low-tax policies (which, by the way, include not just the 12.5 percent rate, but lax transfer pricing rules and patent boxes and other wheezes which can cut effective tax rates close to zero) have been successful in attracting multinational investment.

They certainly must have done – but just how relevant is this anyway? What we want to know is not whether these policies have been good for one sector, but whether they have been good for Ireland as a whole. If Ireland has had to shower investors with tax subsidies to get them to come, meanwhile losing tax from those who would have invested anyway, the cost may well not have been worth it.

On this less important metric we haven’t seen any clear demonstration as to whether Irish corporate tax policies have helped Ireland or not.

We’d argue that Ireland’s key selling point for U.S. firms has been its combination of English language, close cultural historical and economic connections with the United States, its educated workforce (including many immigrants, educated on someone else’s dollar) and its membership of the Eurozone and the EU single market. The graph shows clearly how important the latter factor is, though it doesn’t discount the tax offering. (We should also mention Ireland’s Wild west financial regulation — what they liked to call the “flexible and business focused tax and regulatory system” which brought in a lot of shark-related business, eventually contributing to the Global Financial Crisis and the Celtic Tiger’s spectacular flameout.)

Most of these aren’t easy to replicate: after all, how many other English-speaking Eurozone members with deep cultural connections to the U.S. can there be? Tax is certainly one factor that attracted some investors, but the weight and range of these rare (and mostly good) Irish attributes suggests that Ireland would have got a good chunk of this investment anyway. In which case, it has probably thrown away a lot of tax revenues to the shareholders of a bunch of U.S. multinationals, unnecessarily.

Let’s not forget, too, that there is investment and there is investment. Stuff that gets lured to low tax countries generally tends to involve a lot of accounting nonsense, rather than real economic activity. If it’s tax-sensitive then it is, by definition, flighty, and not so embedded in the local economy. But it’s the embedded stuff (that isn’t tax-sensitive) that countries generally need to attract: the stuff that brings real jobs and skills transfers and so on.

The trouble is, those making huge profits from the accounting nonsense are designing Ireland’s tax policies and are key players in the spin machine that protects the Ireland tax haven. And most of Ireland’s media and political class seems to have drunk the Kool-Aid — as have many others, elsewhere, who point to Ireland as the poster child.

How sustainable is all this? The graph doesn’t provide answers, but it’s surely true to state (as Jim Stewart does in this 2015 discussion paper) that:

“a tax based industrial policy will not result in an innovative, research led economy.”

Indeed.

Endnote: The UK

The UK has tried to emulate Ireland recently in many of these things. Like Ireland, it has the English language and interconnectedness, in spades, though it isn’t a member of the Eurozone. This means two things for our analysis here. First, it shows that Ireland is trapped in a race to the bottom with the UK (and over time, perhaps with Northern Ireland and Scotland joining in this fools’ errand). Second, the evidence so far suggests that the UK’s corporate tax-cutting policies have failed comprehensively to bring anything more than a few jobs for bean-counters, at huge cost.

In the UK, it seems pretty clear that the corporate tax nonsense has been great for multinationals and their shareholders – but not so great for the country as a whole (more on this in due course.) Is it the same story for Ireland?

Read More

Take a look, again, at Barry’s paper, which looks at quite a bit of the history of this tax haven activity, and at the Tax Justice Network’s rollicking history of how Ireland became a wild-west tax and financial regulatory haven, and all the associated links. See also Jim Stewart’s paper Corporate Tax: how important is the 12.5% corporate tax rate in Ireland?

Data Sources

There is a certain amount of data on Irish GNP here. The latest data doesn’t go back far enough, so we had to use reports going back a few years, such as here. This doesn’t yet get you to the GNP/capita as a share of EU GNP capita, so for that we used the data set here (p24), and this one, (p27), to get the final graph. We could have simply used this last data to create an even more dramatic picture but for countries like Ireland where ‘local’ corporate profits are often little more than accounting nonsense with few connections to the local economy, then GNP is a better measure than GDP, if you want to know things like whether this stuff is making Irish people’s lives any better or not. We assumed that European average GDP was the same as average European GNP over this time, which is pretty reasonable because this is usually the case with countries: Ireland (and Luxembourg) are extreme outliners: see Figure 1 here, for instance.

For the net agriculture payments (dark green line in top chart, and third chart), it’s here.

The main blue line in our graph is a good-enough approximation to show what’s going on. You can quibble with it, of course. For one thing, the data set of countries changed slightly over time, from the EU-12 to the EU-15. Doing all the legwork there won’t make much difference. We also only had data going back to 1960, but we wanted to go back to 1955, the year before Ireland’s tax haven strategy began. We didn’t have the pre-1960 data, so we created a short flat line there. (If you have the earlier data, please let us know.) You can also quibble with the timings we’ve expressed here: some of these tax changes were somewhat more complex than we’ve been able to fit into our little captions in the graph. For instance, the introduction of the 12.5 percent tax rate also involved expanding the range of what qualifies for that rate.

* Modern Monetary Theorists and others may quibble with this line, arguing that tax revenues aren’t entirely necessary for spending, but the fact is that governments for whatever reason generally feel they need to match spending with revenues, more or less, over the long run, so there is a loose relationship.

Just wondering as Irish economic history is beyond my pay grade….how the article manages not to use the word ‘debt’ even once.

Can’t Ireland’s rise just be summarized as—it was one big debt bubble?

“Can’t Ireland’s rise just be summarized as—it was one big debt bubble?”

Pretty much….

http://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?g=13WQ

The red line is just bank credit/gdp , but gives a longer-term view. The green line is probably a better indicator of current economy-wide private debt/gdp levels. Gov’t debt should be added on to get the complete picture.

It should be a no-brainer to show rapid gdp growth if you throw 20%-plus of gdp in debt at the economy , year after year , as Ireland did starting in the ’90s.

That housing graph was effectively the debt part of the story. Not the whole story, but a big part of it.

Ever had a song stuck in your brain, can’t get it turned off no matter what you do? “It’s a small world, after all” is my personal hate.

The musical bit about “12.5%” seems to maybe be part of the same disability. My personal economic stuck-song is the one with all the verses, by Grover Norquist and his backup band, that hammers the idiot notion that taxes, far from being the price we pay for civilization (except for lots of footnotes relating to political-opponent abuse and regulatory capture and mercantilism and all that), are some alien imposition by something that’s featured in one of those verses, “BIG SCARY GOVERNMENT!!!”, to be evaded and avoided and warped to one’s personal and corporate benefit full on, all the time.

But there are more features and pathways and interconnections in all of this economics stuff than in the “Krebs cycle,” which cycle at least became somehow designed to regulate energy flows and respiration and all that to keep our sad bodies healthy and growing within the limits prescribed by the basic plan. Dare one note that the added complexities, like essentially unregulated “capital flows,” into zero-bound labor markets and stuff like derivatives and various Dark Pools and so on are painfully reminiscent of the disease processes of various cancers?

Taxes are what give money value.

Government spending to protect ‘civilization’ does not come from taxes.

Taxation is a tool to regulate inflation.

Why you should pay US taxes on foreign income from, say, teaching English in Ukraine, is a mystery…because that has nothing to do with American inflation or domestic unemployment.

good comment. and lowering the corporate tax rate below the cost to society is an immune deficiency thingy. Interesting above about how it was not a competition race to the bottom that turned Ireland into a “tiger” but joining the EU and (I assume) better trade which was not distorted until the credit tsunami – which was totally out of proportion to any stable economy anywhere. So taxes would have kept things in better balance and prevented the worst of the flame out. But I think there is more to it than that because the world reached critical mass simultaneously, not just Ireland. We need a mechanism besides good taxes which keep societies in balance which can deal with tsunamis – like an early warning system and a reserve fund or stg. Maybe the new push for “stability” is it. What to do about laundered money in the trillions is all part of the problem.

Yeah, the EU bit is needed to be included. Microsoft for instance bills all their sales within the EU zone to their Ireland office.

How about Singapore? I believe corporate tax rates are also low there and things on the outside seem pretty good although a lot of the high paying jobs seem to go to foreigners.

I just looked up Wikipedia, List of Countries by Tax Rates.

Barhain: 0% corporate, 0% individual tax rates.

I wonder how they regulate inflation and unemployment. What drive the demand for their currency, the Bahraini Dinar? Is it backed by oil? Gold?

I notice in 2008, the inflation was estimated at 7%, which the citizens of that country must weigh against not losing 20% or 30%, every year, to fight that 7% annual inflation.

The single corporate income tax in Bahrain is levied on oil, gas and petroleum companies at a rate of 46%. This tax is applicable to any oil company conducting business activity in Bahrain of any kind, including oil exploration, production, or refining, regardless of the company’s place of incorporation.

Eventually the oil/gas will run out.

Singapore is not a tax haven. Ireland is.

Singapore’s success is based on Lee Kwan Yew devising a national strategy when Singapore got its independence from the British Empire and had pretty much nothing going for it. He decided that what Singapore needed to succeed was to have a highly educated work force and to be a clean place, from a legal standpoint, for doing business.

Singapore is a huge shipping port and also is significant in electronics assembly.

Do Singapore’s casinos, the frank money betting kind, have anything much to do with that domain’s success?

I have my own way of analysing tax havens and although Yves is right about those particular aspects, on my way of looking things it is a tax haven. http://www.financialsecrecyindex.com/PDF/Singapore.pdf

Singapore has quite a lot of things going on. They have low personal income taxes and will cut private deals with individual corporations to implement zero rate corporation tax when it suits them.

They have an excellent geographical position for sea freight and airline travel. Massive container port, Singapore airlines, budding aerospace repair industry. Huge, competent and efficient shipyards (Sembawang and Kepel). Tons of retail centers, entertainment outlets and restaraunts aimed at millions of tourists.

They sustain a regional financial center, a safe haven for multinational banks to operate in the SEA region. Massive wealth management industry, Casino’s and healthcare catering to super wealthy and corrupt Indonesians, Thais, Chinese etc.

Constantly growing population driven by a racist program of ethnic Chinese immigration, requiring huge investment in infrastructure….. Roads, subways, storm drains, condominiums, apartment blocks, shopping centers etc. Supported by a mother sucker of a housing bubble and low, low interest rates. When the island is finally saturated and the music stops, things should get interesting.

Attraction of multinational corporations to place their regional headquarters in Singapore with lots of high paying executive jobs and expats. They also attract higher value add manufacturing and R&D e.g biotech and pharmaceuticals. Most of the lower value add work has moved to Malaysia or China already.

Massive petrochemical installations on the offshore islands, refining and producing chemicals for the region. A sizeable defense industry. They have a US base and nominally kiss the USA’s ass, facilitating the pivot to Asia. I assume the also keep China sweet too. You can’t go to a party without at least one CIA spook or ‘private’ naval intelligence analyst hogging the buffet.

The British built Singapore into “Gibraltar of the East.” It was already pseudo-developed by independence. It’s also an island city-state, easy to concentrate capital.

singapore is far and better than neighboring country such as indonesia regarding taxes for corporates, that’s why their place is safe haven for them. recently Indonesian goverment put pressure on online business, see here http://tipsta.blogspot.com/2015/04/pajak-bagi-bisnis-online.html

A big part of the Celtic “tiger” is just accounting fiction. Large corporations all over the world engage in complicated shenanigans to count income as coming from fairly skeletal Irish subsidiaries.

Your analysis on GNP avoids most of the distortions (although not all) because it excludes profits of foreign nationals but it’s still an important point to raise.

Good article, and correct in principle, although I’d like to add a few more details and caveats.

It was never a core element of Irish industrial policy to use low tax as the core of its appeal to multinationals. It was initially intended that low corporate tax would be used to lure relatively low skilled ‘screwdriver’ plants for small towns and rural areas. it was accepted that these were largely fly-by-night operations, but this was seen as a price worth paying in order to provide jobs in very depressed regions. Back in the 1960’s and 70’s there was quite a distinction made between this sort of development and what were seen as more strategically important industries, which were pushed towards ‘clusters’ in line with development theories fashionable at the time. But even then, low tax was just seen as one element in attracting foreign companies – it was always held that having a young, English speaking workforce was just as important.

Later, when Ireland became a major centre for IT, the big attraction was the plentiful supply of mid-level graduates. I had a friend who worked for the IDA, the main government agency involved then, and he said that it was amazingly easy to get the Silicon Valley companies to set up in Ireland. Most of those companies were very new, their management was very inexperienced when it came to international expansion, so they were relieved to find a country that spoke English, had a legal/regulatory system that didn’t seem to strange, and was willing to do all the hard work (finding land for factories/offices etc) for them. The tax incentives were seen as something of an ‘icing on the cake’ at the time (although it was always known that Apple had special arrangements for them – they were the very first of the big Californian IT companies to come to Ireland). It must be remembered that while Google, FB, Yahoo, etc., use Ireland as a tax haven, they also have very large, and very real investments, most of them have their European hubs in Ireland, and thats for reasons largely separate from tax.

It was in the late 1980’s, when Ireland was in the middle of an intense self-inflicted recession, that the notion of becoming a sort of off-shore financial haven to take some flotsam from London became policy. For me, thats when industrial policy in Ireland started to rot – instead of a proper rational system of picking winners and attracting them to Ireland, it really became the wild west, at least as far as financial firms were concerned.

In macroeconomic terms, I don’t think the situation is a simple as the analysis above set out. In Piketty terms, Ireland’s growth in the 1990’s was largely just a catching up on the mean. A combination of bad luck, bad timing, and some awful policies meant Ireland never shared the economic expansion of the 1950’s and 1960’s with the rest of Europe. A mini-Celtic Tiger (helped by joining the then EEC) had started in the late 1960’s, early ’70’s, but was cut off by the Oil Crisis. In the late 1970’s some very misguided policies (a sort of bastardised Keynesianism) let to a ridiculous overheating of the economy, which crippled the Irish economy while everywhere else had the mid-1980’s boom. Much of the 1990’s was simple catch up to the European average, aided by favourable demographics.

The notion that it was all EU transfers and bank debt which led to the Celtic Tiger is simply not true as it predates these effects. The Tiger started in the early 1990’s, partially due to increased EU investment, but also due to demographic factors (a very low dependency ratio) and a boom in foreign investment. The graph showing a ‘property bubble’ from the mid 1990’s is misleading. Rises in property values are not always bubbles. In fact, a combination of a very young population with a sudden, and huge increase in immigration (proportionately, one of the largest one-off influxes of population ever recorded internationally outside of refugee crises) meant there was a massive shortfall in housing and commercial property. The massive rise in property prices in the late 1990’s and the rise in debts then was almost certainly ‘justified’ by simple supply and demand and the huge rise in working population. It was only after the economic blip around 2001 that a true bubble developed. It was around 2003 when there was no longer a shortage of property relative to demand – thats when it was clearly a bubble. In reality, the true bubble economy was from around 2003-2007, not earlier as suggested above.

I was working in a large US tech corporation in the 90’s involved in the setup of a massive factory in Ireland. There were several other tech companies doing the same at the time.

A manufacturing foothold within the EU to protect against potential trade barriers was the number one criteria. English speaking was desired. The UK was briefly considered, if I remember correctly the rationale against the UK was slightly more expensive workforce, some guff about unions, not in the eurozone and higher tax rates. The goods had to be shipped to England from Dublin and trucked to Dover before reaching the continent, but the tax advantage and other incentives offered by Ireland were juicy enough to make it worthwhile.

Without the distortion of taxes and other Government incentives the optimum location would probably be at the center of European distribution around abouts the Benelux region.

“Later, when Ireland became a major centre for IT, the big attraction was the plentiful supply of mid-level graduates. I had a friend who worked for the IDA, the main government agency involved then, and he said that it was amazingly easy to get the Silicon Valley companies to set up in Ireland. Most of those companies were very new, their management was very inexperienced when it came to international expansion, so they were relieved to find a country that spoke English, had a legal/regulatory system that didn’t seem to strange, and was willing to do all the hard work (finding land for factories/offices etc) for them.”

I was glad you brought that up. I worked in the trenches in Silicon Valley from 1989 through 1990, which included thoroughly combing COMDEX, and all other tech trade shows in Silicon Valley as well as other out of state tech trade shows. Ireland (and Canada) always had a very modest booth amongst the hundreds or thousands of booths represented, graciously, charmingly and relentlessly soliciting for Ireland to become one of the Tech manufacturing, and whatever, partners of the world. Having an English-speaking, educated workforce was the key selling point, and indeed, the recessions and the wax-wane cycles of tech as well as the economies specifically, played into wanting to latch onto the engine of Silicon Valley.

The fact that they coordinated whatever tax strategies that they could, certainly indicated that they approached their intention comprehensively, as did Canada, though to my knowledge, the outcomes are not parallel.

One of the major points overlooked by most foreign observers was a strategic decision taken by government in the early 1990s.

At that point Ireland had a creaking telephone system introduced by the British in the 1920s.

By the late 1980s the system was creaking under the strain of ‘modern’ domestic use.

The decision was taken by government (and state business-attracting organisations) to totally upgrade the telecommunications infrastructure. Because Ireland is small geographically as well as english speaking and a member of the (erstwhile) EEC, it became the only state in Europe to have all of these facilities in place just as the internet/international communications boomed.

With a cool climate and plentiful supply of fresh water, US corporations could encamp, manufacture and communicate globally like nowhere else on earth.

This is the root of the celtic tiger; like everywhere else the lower corporate tax rates were the result of spooked/bribed politicians. Just a bonus to the corporates.

If anything, Ireland provided a template to the corporates that they could bully and bribe legislation to their advantage.

(anon name and email used – hope you allow the comment)

This is one of the reasons I like posting to NC: the comments are always interesting and well-informed. Thanks.

As I read the above and look at the graphs one thing jumps out at me that seems to be over looked and might cause the graphs to be irrelevant and that is “The Troubles.” Living in Europe in the late 80’s there was always the possibility of an attack by various groups like the IRA, Baader-Meinhof and the Red Brigade. Because of these actions I believe American Corporations were very reluctant to relocate any where there was much activity by these groups (I should also mention besides the IRA there were various protestant groups also active in Ireland). Basically you had a low-level war going on. The Troubles lasted from the 60’s to the Good Friday Agreement in 1998. When I look at the graph above what do I see, “Oh economic activity started ramping up right around the signing of that agreement. Is that the sole factor! No, but a large contributor. Hell people would not even take a vacation in Ireland during that time due to the violence.

I would also note that just because you have a low tax rate does not mean that there is not adequate money to run the government. For instance Ireland does not have a military-global police force to throw money away on. Then in the US there is the Davis-Bacon law that causes infrastructure build out to cost 3 times as much as it should. I could see a small island like Ireland ran very well on that tax rate. I would also note that other places like Malta even have lower corporate tax rates.

Why are we still referring to Reinherdt and Rogof??

And in picking up Silicon Valley’s newspaper of record, The San Jose Mercury News today – Sunday Edition, I see this article:

http://www.mercurynews.com/Business/ci_27709010/Apple-brings-hope-to-Irish-town-used-to-exodus

Wonderful that Apple is able to bring “hope” via spending up to $1B on a data center the size of 23 football fields. The main benefit is the 300 jobs it will add over the LIFETIME of the project, mainly in construction (adding to the 4000 jobs they have already created there. How great ~ they won’t be losing population (???) due to this. Operational costs will be lowered due to the cold climate.

And ~ US companies have INVESTED about $277 BILLION in Ireland since 1990 ~ exceeding Brazil, Russia, India and China, COMBINED.

The 12.5 tax doesn’t hurt, either. When you factor in the http://www.investopedia.com/terms/d/double-irish-with-a-dutch-sandwich.asp ~ it’s downright irresistible.