By Rob Parenteau, CFA, sole proprietor of MacroStrategy Edge and a research associate of The Levy Economics Institute

Paul Krugman had a delightful field day with his March 2nd New York Times column trashing media poseur economists like Larry Kudlow – economists who somehow manage to survive on their entertainment value alone, despite their repeated analytical errors. No doubt their prolonged shelf life has more than a little to do with the fact that the points of view they espouse tend to encourage their readers (or viewers) to think that their self interests are perfectly aligned with the self interests of say, oh, the Koch Brothers and their ilk. Useful idiots is the phrase that comes to mind. Useful idiots engaging in willful ignorance.

On his way to skewering the clownier clowns of the economics profession, however, Krugman could not help but to once again remind his loyal readers that everything you ever needed to know about macroeconomics was already discovered and described in his 1998 paper on Japan’s alleged liquidity trap. Humility is not one of Krugman’s strong suits, but we will allow you to come to your own conclusions after reading yet another of his repeated attempts at shameless self pimping in the March 2nd piece:

In my own case, I’d guess that about 80 percent of what I’ve had to say about macroeconomics since the crisis was prefigured in my 1998 liquidity trap paper, which was classic MIT style — a stylized little model backed by and applied to real-world events, with lots of data used simply. (Seriously, skim that piece and you’ll see why I sometimes seem so frustrated: People keep rolling out arguments I showed were wrong all those years ago, or trotting out arguments I made back then as something new and somehow a challenge to conventional wisdom.)

Now let’s conveniently forget for the moment that Krugman really doesn’t have a clue about liquidity traps, at least as Keynes presented them. Jan Kregel pointed this out over a decade and a half ago, but perhaps Krugman has not gotten around to reading that piece, since Krugman did not write it…and everything you need to know about macro, according to Krugman himself, is written by Krugman. You can read Jan’s argument here if you care to discover where Krugman has gotten Keynes’ liquidity trap wrong, especially as it applies to Japan’s deflationary lost decades.

Since Krugman wrote the introduction to the latest edition of Keynes General Theory, which is where Keynes lays out the liquidity trap issue, this might be a source of embarrassment to a liberal, especially if he indeed has a conscience. But as Jan points out, in the world of Very Serious Macroeconomists, there are people walking around calling themselves New Keynesians, when really they are just Old Friedmaniac monetarists, with a little pre-Great Depression Irving Fisher, and maybe a dash of 19th century Wicksell too, thrown in on the side for good measure. And they get away with it. Somehow. Like Kudlow does.

New Keynesians like Krugman, Bernanke, Blinder, Yellen, etc. believe they have found a hammer, namely Irving Fisher’s real interest rate hammer, and so the whole economic world looks like a nail to them. Got an unemployment problem? Lower real interest rates. Got an inflation problem? Raise real interest rates. Life is simple, and life is good. It’s all there in Krugman’s 1998 paper – seriously, skim that piece.

In that world, we are encouraged to forget about fiscal policy – government debt to GDP ratios are too high already – just ask Reinhart and Rogoff – and so few developed markets nations have the policy “space” to use fiscal stimulus, ever again, apparently. Even if they have sovereign currencies. Instead, monetary policy is deemed hegemonic.

And by the way, now that even central banks like the ECB are doing QE, monetary policy is fiscal policy. It is just that rather than using money to produce something useful and increase household incomes, which is what fiscal policy usually does, and is so unfashionable, money is being used to produce capital gains for bondholders, and maybe even equity holders as well, if the portfolio balance channels are not too clogged. The only problem seems to be that bond and equity holdings are highly concentrated in the highest reaches of the income distribution, so this is just trickle down economics in New Keynesian drag.

But putting that all to the side, there is a big black fly doing the back stroke in the New Keynesian policy soup. And nobody dares call the waiter over – it is all just a little too embarrassing. And nobody dares to clue Krugman into the insect intrusion, because he did not write about it, so it has not been discovered yet…has it?

Matthew Klein reported in Tuesday’s FT Alphaville on some findings delivered by Goldman Sachs economist Jan Hatzius, who is no clown, and BAML’s Ethan Harris, to the Chicago Booth Monetary Policy Forum last week. As displayed in the FT chart below (full article linked here) there is a little problem with the widely received and deeply believed story that real interest rates are the one and only steering wheel of economic policy.

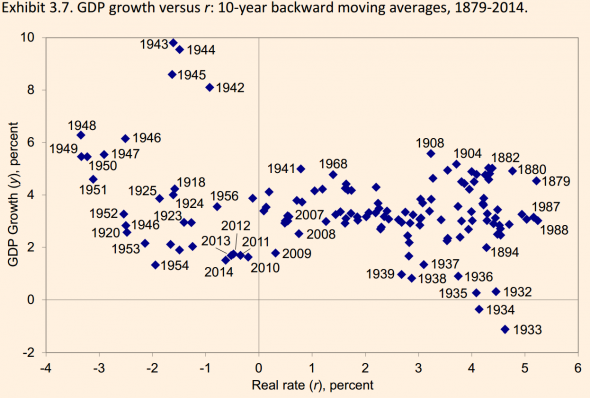

As you can see for yourself in the chart, over the past 135 years, there is not much of an inverse relationship between real interest rates and real GDP growth rates over the long run. We should concede the point that the expected inverse relationship between real interest rates and real GDP growth does appear to show up only at the extreme high and low levels of real interest rates. But notice the dates on these observations at the tails of the distribution.

Real GDP last reliably rose with low real interest rates in the late 1940s and early 1950s. They also last reliably fell with high real interest rates in the 1930s. So that means Krugman, rather than Keynes, appears to be practicing “Depression Economics” – that is, an economics only relevant to long ago and far away, which is basically how Krugman interprets Keynes, but that is an issue we’ll take up on another day.

Prof Krugman has plenty of wiggle room left for his arguments. He is one of the first to recommend 750 B USD stimulus in 2008. His problem is he has not figured out the rigth mix or tradeoffs between fiscal and monetary policies. But the fact of the matter is nobody else has figured it out either.

During the deficit debates, Krugman took the position that the US should balance its budgets eventually. If you understand sectoral balances, that’s an austerian position. An economy has four sectors: households, businesses, government, and import/exports. We’ll keep imports/exports out of the picture, since it does not change the conclusion in the case of a country that runs chronic trade deficits like the US.

The savings of the household, business, and government sector need to sum to zero. That’s double entry bookkeeping.

Households (except for a brief highly anomalous period in the early 2000s) are net savers. They in aggregate save for emergencies and retirement.

We like to think of businesses as net spenders. They in fact should be net borrowers to invest in growth. That is why it is not popular to have the government run deficits. They are assumed to crowd out business investing.

In fact, the government has been a much bigger spender on basic research than the private sector, precisely because the private sector can’t bear that level of risk. And since the early 2000s, the business sector in aggregate has been a net saver. Note that this is NOT the result of the crisis, in fact, this is a pervasive pattern across all advanced economies and even in a lot of developing economies ex China.

In those circumstances, you NEED the government to run deficits or else the economy contracts. And in fact, the evidence is every time the Federal government balanced its budget, we’ve had a recession.

So Krugman is wrong in a more fundamental way than your comment indicates. And he now supports the “secular stagnation” hypothesis, rather than calling for more stimulus.

If your only critique on this particular score is (whether you are explicitly saying it or not), “well, Krugman may have been mainly right about the prescription for the current crisis, but wrong about long-term budget balancing,” you’re 1) disagreeing with both Krugman and Keynes, in a way that disagrees with the main emphasis of the post in question, 2) eliding the fact that you actually agree with him on the policy prescription for the current status, and 3) undercutting the entire point of this post. You both feel that $750 was too small– you both said it at the time (I read both of you). You both say that fiscal stimulus is preferred to monetary. You both say that deficit spending in a recession is fine. Possibly you disagree on the long-term budget position in the case that housing and business spending are insufficient to sustain demand, although frankly both of you would advocate significant government spending on research, infrastructure, and other things the private sector can’t do well.

I get that you disagree on the way banks and modern money creation work, and you may well be absolutely right and Krugman wrong, but those things have no bearing on what either you or Krugman have advocated to *get out of* a liquidity trap. You both turn to fiscal stimulus by preference. It’s a little silly to take your fundamental argument about the workings of money and turn it into a critique of Krugman for things he did not, in fact, do, particularly as you’re on the same page on this one.

Krugman believes in the loanable funds model and that lead to a LOT of erroneous thinking. We’ve discussed this at length.

Krugman has long ago stopped saying in any serious way that more fiscal stimulus is needed now. In fact, he’s applauded that deficits are falling as opposed to saying that that is not what we should be doing now. He’s instead been focusing on interest rate policies, and not even bothering with the presumed caveat, “They are better than nothing” which is a dubious proposition.

In other words, Krugman is far more conservative in his positions than you indicate.

Also, while Krugman has looked at some secular stagnation research and said in essence “well, maybe,” he also said, “but that’s different from than a supply-side slowdown, and the solution is still stimulus, maybe in the form of infrastructure spending.”

Again, if your solutions are the same, why so much harping on the diagnosis?

He has not said the solutions are the same:

This is a really important distinction, because secular stagnation and a supply-side growth slowdown have completely different policy implications. In fact, in some ways the morals are almost opposite.

If labor force growth and productivity growth are falling, the indicated response is (a) see if there are ways to increase efficiency and (b) if there aren’t, live within your reduced means. A growth slowdown from the supply side is, roughly speaking, a reason to look favorably on structural reform and austerity.

But if we have a persistent shortfall in demand, what we need is measures to boost spending — higher inflation, maybe sustained spending on public works (and less concern about debt because interest rates will be low for a long time).

So please, let’s not confuse these issues. This isn’t some academic quibble; we’re trying to understand what ails us, and saying that high blood pressure and low blood pressure are more or less the same thing is not at all helpful.

http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/10/27/what-secular-stagnation-isnt/

Yes- are you reading this as an anti-stimulus argument? “That is, we will often find ourselves facing persistent shortfalls of demand, which can’t be overcome even with near-zero interest rates.” […] “But if we have a persistent shortfall in demand, what we need is measures to boost spending — higher inflation, maybe sustained spending on public works (and less concern about debt because interest rates will be low for a long time).”

He is saying, very explicitly, that even if secular stagnation is real, the policy implications are the same as for a purely demand-side recession.

“maybe sustained spending on public works” is weak and highly qualified. That falls well short of saying the problem is a shortfall in demand. The secular stagnation hypothesis in part argues that demographics and workforce quality are the problem, and explicitly relies heavily on the loanable funds mode. In fact, workforce participation is highly variable over time and tons of people who are older would work if they could for income reasons alone, so this demographic aging population bugaboo is way oversold. It also blames the US workforce for its low skills (the Summers speech has references to this), as opposed to the failure of capitalists to invest in expanding their businesses and creating jobs. Summers actually acknowledges low investment first and foremost in his famous secular stagnation speech, but he refuses to acknowledge that 1. Tons of studies show that businesses seek an unreasonably high rate of return and 2. Institutional factors, namely stock linked pay and equity market short-term-ism, have made that worse.

Apart from our discussion of that, if you believe that story, you would acknowledge the need for virtually permanent fiscal deficits to make up for capitalists’ over high profit targets, with the government cutting back only when the economy was overheating (or better yet, having heavy emphasis on programs that are naturally countercyclical, since politics makes it hard to cut spending, since that means goring someone’s ox).

By contrast, Krugman is clearly looking to create more inflation as the first line of defense, that’s the only idea he endorses without reservation. That implicitly is a call for monetary policy solutions. And the qualified call ONLY for infrastructure spending is to create more low skill jobs (as well as acknowledging that recent paper claim infrastructure spending has a high fiscal multiplier, but again that is more evidence that he believes that it is important not to let debt/GDP ratios get too high, as opposed to taking the point of view, “Take care of the economy, and the deficit issue take care of itself.””

Yes, but he calls for infrastructure spending not only in that post, but often. And of course he has called for many other forms of public investment. And he says, in that very post, that secular stagnation would result in a persistent shortfall of demand (a far cry from “falls well short” of saying this- he says it). In a number of prior posts, of which that is a culmination, he was saying that secular stagnation is false– but he’s revisiting some more evidence here from the Davies article, which itself says: “Is this ‘secular stagnation’? The term is interpreted differently by different schools of economists. Some believe that the disappointments in growth since 2009 have been mainly due to persistent shortages of demand because of balance sheet problems after the Great Recession, while others attribute them to a slowdown in supply potential over a longer period of time. The Fulcrum study does not attempt to settle this debate. ”

Krugman is responding to a post about a study which is possibly refuting some of Krugman’s own very recently prior contentions that secular stagnation is bunk. And his takeaway, even then, is that it’s a demand-side problem, and infrastructure spending would help. You differ greatly on the interest rate argument, and certainly on the question of running long-term deficits, and the effectiveness of monetary policy generally– but not really on the question of a demand side recession and the value of stimulus. You are really overestimating that difference, I believe.

That said, *I* agree that secular stagnation is not the issue, and that real industrial policies (and I use that term broadly, not in its sense of “encouraging manufacturing, but in the term of “enabling everyone willing and able to find a decent-paying and sustainable job”) are the answer, and require tremendous public investment. I’m not sure Krugman would disagree in the long run either, but it’s moot to the short-term argument about current conditions, where I think we all agree.

Yves, I learn much from your comments that I appreciate without measure. This said, why do you state, “And the qualified call ONLY for infrastructure spending is to create more low skill jobs…”? Do you not consider clean manufacturing that is a component of today’s infrastructures more a technical skilled job vs. “low skill”? I think that’s part of Summers argument that he questions ‘retooling’ and more education is needed. If I misunderstood you I recant in advance.

Clean manufacturing is not “infrastructure spending” in Washington speak. As the Ron Suskind book Confidence Men makes clear (there’s an incident at the very start of the book where someone throws out the idea of “infrastructure spending” as part of the 2009 stimulus bill, and Obama grabs onto it because it creates manly jobs. “Infrastructure spending” is roads, bridges, high speed rail, airports, as in construction projects of various sorts. Even though the DARPANET, the precursor to the Internet, wound up being critically important infrastructure, no one classifies that as infrastructure spending. It was military-related R&D, a backup communications network.

And infrastructure to this administration, as the 2009 stimulus demonstrated, is “very visible infrastructure” like paving jobs and replacing bridges that had replacement plans-n-specs already on the shelf. Not more complicated things like sewers, wastewater treatment, and water supply projects that were painstakingly constructed in the 1930’s and have a 75 year design life.

Actually, Krugman said very directly at the time that $750 billion was too small. And he recommended QE only in lieu of fiscal policies that he believed were unworkable in the given political climate, although much preferred. He has advocated deficit spending, and large amounts of it. There is certainly much to critique in Krugman, but little of it shows up here. The misrepresentation that he believes interest rates are the best and only mechanism in the current economic climate, the odd notion that he dislikes stimulus, the lumping of him with Reinhardt and Rogoff when he has devoted significant time to discrediting their current work… this all makes it appear that the writer has actually not read Krugman– the very crime he accuses Krugman of. Funny stuff.

I suggest you scroll to the end of the comments and read what Parenteau has written. QE is no substitute for fiscal policy. And why should Krugman gag himself in light of prevailing views in DC? What exactly is the point of having a NYT column? Krugman had no problem with being way outside the DC orthodoxy early on the Iraq war. If he really believes in fiscal stimulus, he should call for it, rather than keep defending the Fed’s failed monetary interventions. The fact is that he is deeply loyal to Team Dem and not willing to call them out except in the most cautious manner.

I agree that QE is no substitute, but so does he– as do you. I think he’s just made a calculation that the current congress provides no possibility of stimulus– as have I. That could be wrong, but I think he believes that he is putting his policy effort where it may be meaningful (although he simply disagrees with you on monetary intervention, or at least, feels like at worst it’s harmless, and worth attempting, and that he has some traction there– but he doesn’t see this as a repudiation of stimulus, as far as I can see) This is not to say that he has abandoned saying, periodically, that fiscal stimulus is important– this pops up fairly regularly, and of course just in the last week he has pointed out on a couple of occasions that the predictions of the deficit hawks were ludicrous, but I don’t think any evidence in his writings or anywhere else indicates that he’s had a change of heart or mind on the effectiveness of stimulus. It takes a very willful misreading to get to that understanding of his beliefs.

I don’t find the comments you reference particularly trenchant; yes, Krugman calls for sustained inflation (and why not), but while in the Japan case he seems to disbelieve in the possibility of enough stimulus, he certainly advocated it strongly in the U.S. case. And doesn’t the U.S. case prove that he was correct in despairing of the ability of politicians to enact an appropriate stimulus? It came in much smaller than you or he advocated, for purely political reasons.

In addition, I think his shift to harping regularly on the need for infrastructure spending is a way at the stimulus argument by other means– it’s the least controversial, most tangible form, and it’s obviously needed for more than just job-creation… why not just put your policy-prescriptive energy there? I think it’s a deliberate calculus on his part that there is more chance of actually getting some stimulus that way. More timid than you would like, perhaps, but se la vie, se la guerre.

I’m beginning to suspect that I pay much more consistent attention to both of your actual arguments than either of you do to each other’s. I wonder who is most unhealthy in that equation?… Probably me.

kibost: As Susan has recommended, please work your way through my extended responses starting this morning which pull quotes directly from the paper Paul himself declares, glowingly, is his major contribution to solving liquidity traps, which I think he still believes are an issue to be dealt with. If that does not make you healthier, at least it will make you better informed about what Krugman the economist says in Very Important Economic Journals Respected in the Profession, versus Krugman the NYT columnist…though I suspect if you looked hard enough you would see the columnist is actually saying pretty much the same thing as the economist…and to his credit, Paul can play both of those roles, and he plays them well. He is just wrong in some cases – like real interest rates making much of a difference for real GDP growth in the long run at least, which by his own admission, is what is it going to take for policy to win against liquidity traps and/or secular stagnation. Where as Larry Kudlow can only do the clown act, and that is all he has ever done, and he unfortunately wasn’t that good at it either, though I am sure he would beg to differ, as would the man who used to fill his silver spoon back in the day. (I remember this guy from the ’80s when he was the Bear Stearns economist and he would sit at the end of the table pontificating in a slightly Lafferesque but always very Thatcherian fashion while chain smoking away, and looking out the window frequently as if he could not wait to get to the bar afterward – but hey, he was entertaining, and my memory may be failing me, so take all of this with a gram of, no I mean a grain of that other white crystalline stuff…yeah, that would be salt, right?

Yes, I did read your comments (they are not so dense or difficult that “work my way through” is exactly descriptive, no offense– I simply read them in their totality); I am not disagreeing on some of your or Yves’ points, I simply disagree that Krugman is anti-stimulus, or that he ever felt that the U.S. stimulus was adequate, or felt that QE was an adequate substitute. And I have read a certain amount of his academic work at various points (primarily journal and conference articles), so while I appreciate what is, I will charitably assume, your well-intentioned although in fact totally concern-trolling attempt to further my education, it is somewhat redundant. I don’t disagree that he feels interest rates have much more traction than you do, nor that he prefers a temporary stimulus- my disagreement was fairly narrowly targeted, and remains apt imho. The Larry Kudlow anecdote is nice though– I will take it as a friendly and funny remembrance you are nicely sharing with me, rather than the “I’ve been in this game way longer than you and here are my war stories so my argument from authority wins” kind of shorthand someone else might take it for.

Sorry if this comes across as snarky; when someone assumes I need “educating” simply because I disagree with them, I find it more than a little condescending. Assuming that wasn’t your intent, however. At another website, I wouldn’t even bother to make the point, but I tend to have a lot of respect for the writers here, so take it fwiw.

With all due respect, you appear to be reconfirming your prior beliefs. Parenteau quotes Krugman at length, in more than one paper. Krugman regards sustained negative real interest rates as the first line of defense against Japan-types situations, and fiscal stimulus as important only when interest rates don’t do the job.

I didn’t disagree with that, or not in the main, although I’m not sure he hasn’t modified his Japan-era beliefs from what he saw in the current crisis. Not exactly the point I was making… actually I don’t think we’re all in disagreement *that* much about what Krugman thinks; my point responding to you initially was more on the lines of what I believe I see here frequently: because of your disagreements with Krugman on some basic aspects of theory, you tend to magnify *all* differences, even at times when you’re largely in agreement. The fundamental differences in your analysis of the economy translates itself into an “always-ever” difference in policy prescriptions, that is not always there.

My response to Rob was, gently, “stop condescending to me. I can read you and still not agree, and my disagreement is not necessarily a sign of ignorance.” I’ll echo that to you: why is it guaranteed that I *shouldn’t* reconfirm my prior beliefs after reading him, and you? The power of your analysis and rhetoric is so irresistible that I must necessarily change my mind? ;-) (sometimes it is, but not always…) However, no harm, no foul.

One is reminded that Keynes – like basically all economists before 1970 – was a disciple of Malthus, and believed that demographics was at least as powerful as finance. Anyone not talking about demographics, and the effect of forced population growth on wages and profits, is at best a hemi-Keynesian. Or perhaps, useful idiots engaged in willful ignorance (wonderful phrase that – I think I’ll steal it!).

It’s an issue no one wants to confront for fear of sounding like a white nationalist maniac or just a crank.

But if we can’t use the resources we have sustainably, everyone, including the exponentially larger amount of people in the future, is screwed.

I’m in favor of a one child policy for everywhere forever.

Yes, because only children are so incredibly socially adjusted.

It takes two to make one, so that would quite likely result in a dwindling population…

Doing it forever would result in extinction.

I believe the amount of children needed to maintain the status quo population is ~2.3 per couple.

A one child policy for a few generations would likely improve conditions dramatically but at some point you need to level off if you want your species to survive.

This is meant as a description of Krugman’s economic worldview?

“In that world, we are encouraged to forget about fiscal policy”

Ummm… I seem to have a memory of Krugman strongly denouncing the 2009 Obama stimulus as far too small economically, and far short of what was achievable politically.

I also seem to have a memory of Krugman denouncing both Obama’s initial inauguration speech as bizarrely focused on balanced budgets, and his disdain for Bowles-Simpson.

I also seem to have a memory of Krugman repeatedly denouncing Japan’s periodic efforts to tighten fiscally.

Finally, I also seem to have a memory of Krugman repeatedly citing FDR’s 1937 fiscal tightening as an example of extreme economic wrong-thinking.

But I guess my memory (and all those publicly accessible writings) must be faulty…

But Krugman thinks that stimulus has to be paid back over the business cycle. (Keynes didn’t, although he left it out of his General Theory.)

But, but, but, but…

Shameful lies.

I call bullshit. Krugman has repeatedly supported the use of extreme monetary measures which as Parenteau has described, increased inequality and have been shown to be unproductive. He’s not called for more fiscal stimulus and during the deficit debates, and Benedict correctly states, REPEATEDLY endorsed the idea of balancing the budget longer term.

And Krugman did NOT support continued Japanese deficit spending, see here:

What continues to amaze me is this: Japan’s current strategy of massive, unsustainable deficit spending in the hopes that this will somehow generate a self-sustained recovery is currently regarded as the orthodox, sensible thing to do – even though it can be justified only by exotic stories about multiple equilibria, the sort of thing you would imagine only a professor could believe. Meanwhile further steps on monetary policy – the sort of thing you would advocate if you believed in a more conventional, boring model, one in which the problem is simply a question of the savings-investment balance – are rejected as dangerously radical and unbecoming of a dignified economy.

http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/SCURVE.htm

This is precisely the type of thing Parenteau called him out for, BTW.

Krugman believes in the loanable funds model, which is something Keynes clearly rejected but “Kenyesians” like Paul Samuelson distorted Keynes to make his theory more amenable to modeling and to make it consistent with neoclassical economics. And Parenteau provides a long form rebuttal later in the thread.

I’m curious about your remark on Keynes. I thought broadly speaking Keynes argued for counter-cyclical policy, possibly mild inflation, not significant and continuously growing deficits? Are you referencing a specific quote or paper? One of Keynes’ most famous lines is about the dangers debauching the currency. From that larger essay:

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/commandingheights/shared/minitext/ess_inflation.html

Keynes advocated for full employment. Period.

The other idea is to advocate for a full share of the pie for each of us.

“I know you can make $billions shorting currencies, but you did not get where you are today all by yourself, did you? I mean, the society must have helped along the way. Don’t you think you should share some of that?”

“I also know you can make $trillions selling driverless electric cars, but you did not get to where you are today all by yourself, did you? I mean, you had to have gone to school, learn from others, and rely on your customers to make you rich, right? Don’t you think you should share some of that?”

It’s possible to dream about GDP sharing.

I’m curious about Benedict’s thoughts.

But the concept of full employment doesn’t have anything to do with the paying back part of the matter. A full employment program could be funded by deficit spending. It could be funded by taxation. It could be funded by a combination of the two. There are two different, unrelated questions when talking about the federal budget:

1) How many currency units should the government spend?

2) What percentage of those currency units should be newly created?

At full employment debt/GDP ratio drops.

I didn’t say anything about government debt, though. Treasury securities merely defer the choice of taxation or money printing into the future. It is not a third source of financing in and of itself.

A full employment system funded by issuing Treasury securities would absolutely increase the debt/GDP ratio. My question would be who cares? Or perhaps more accurately, why do you care? Why is that a feature of full employment that debt/GDP would go down? It is statements like that which is why I think MMT is fundamentally monetarist. It operates within the mainstream view that the quantity of money matters, that a good monetary policy must choose some kind of buffer stock approach.

I’m critiquing this from outside the mainstream. I think only external constraints, political processes outside the monetary realm, can anchor prices over time. No buffer stock approach within monetary policy can do that, whether that be full employment or unemployment or gold or wool. Only political decisions that allocate resources in productive rather than wasteful manners can do that. It’s not the amount of currency units that matters – it is the activity directed by those currency units that matters.

You ask how it “gets paid off”. When someone answers you claim that wasn’t your question.

Washunate – You want to look at Keynes’ proposals for full employment without inflation going into WWII. Required compulsory private sector savings that would be released after the war effort was winding down. Keynes was much less about stabilizing the economy in the short run through fiscal policy OR monetary policy, and more about using interest rates, government infrastructure spending, public/private capital spending projects, and possibly even tax policy to create an economic environment where investment was fairly steady and strong enough to carry the economy close to if not on a full employment growth path with low inflation. His writings in Essays in Persuasion also show while he viewed both inflation and depressions, he judged for a variety of reasons, the first was the lesser of the two evils, but as his policy proposals going into WWII show, inflation was still an evil he would prefer to minimize by design where possible.

By the way, Singapore does this compulsory savings and seems to be able to use it with some degree of effectiveness in countercyclical fiscal policy, though I would not pretend to be an expert on that.

What I find interesting is how that’s exactly the opposite of what we’ve been doing. In 1935, US GDP per capita was about $600. In 1975 it was over $7,000. Today it’s over $50,000. That’s massive aggregate growth. If this kind of growth hasn’t solved our problems, how much growth will it take?

“(Krugman) is one of the first to recommend 750 B USD stimulus in 2008.”

I have no idea if this is true, or importantly, when in 2008 you think he recommended this.

But by January 2009, he was loudly and repeatedly calling the similarly sized administration stimulus far too small economically…

I think a lot of victims will be stimulated by the thought of going after the money looted by bankers ($trillions at least).

But no.

We must all get along – bankers and victims.

Stop dwelling on the past. Let’s all look forward (to more money printing…wait for this…so they can loot again – it’s just a matter of time…they are that ‘smart.’)

Whatever you do, don’t look back (like Lot’s wife, not related by marriage to Lott, I believe).

In this way, we are conditioned, sorry, educated or taught to look forward, always.

Finally, while Krugman is not an infallible pope, the idea in this post that he doesn’t think strong fiscal measures are crucial in a ZLB scenario is just beyond bizarre…

This piece by Partmanteau is filled with lies. Typical for Naked Capitalism.

“filled with lies. Typical for Naked Capitalism.”

I do believe those are fighting words.

A woman, in Northern Ireland at the height of the “troubles”:

“You are a disgrace BBC and you should stop that at once. You’re filming things that are not happening here”.

A news reader at India at the time said: “It’s all maya.”

(Just kidding).

If anyone here is making misrepresentations, it is you. Do you deal with ANYTHING that Parenteau said in his post? You straw man and use that as the basis for your bile. Please see my comments earlier in the thread.

Does you has a sad, Pete? All those big mean liars beating you and Kruggles up.

Petey, not Peter K,

You are right in your statements about Kurgman’s general positions. That is not what Parenteau is critiquing. Krugman uses an ISLM model to describe the economy and in that model, when interest rates approach the “zero bound” the interest rate mechanism fails to work normally. For this reason he calls for stimulus, and did in 08, 09 just as you say.

But because he uses ISLM rather than Keynes general theory, he both believes the stimulus must be paid back and that “quantitative easing” can function as stimulus by pushing the zero bound into negative territory. The nature of the ISLM model implies that if money is subsidized, by negative interest rates investors will be bribed into investing, which is the engine of profits via the Kalecki/Levy profits equation (two independently discovered assessments of the same underlying mechanism of capitalist profit formation).

Keynes, on the other hand, like Schumpeter, believed that money profits, not investments, were the motive of capitalism and that no level of subsidy on money would encourage entrepreneurs to invest in the face of an aggregate demand deficiency because without apparent future demand there is no profit incentive to make the investment. Thus Keynes stimulus is intended to put money in the hands of actual humans, citizens, workers etc, whereas QE just doubles down on investors who, as Keynes would have predicted, have just hoarded it.

In addition Keynes understood that fiscal deficits were necessary on aggregate to expand an economy because reducing the accumulated deficit was in fact deflationary as it soaked money out of the real economy: he understood the chartalist nature of money, having managed GB Treasury through WWI with fiat money, that government spending created money, taxation destroyed it and that govt surpluses were only useful as a tool to dampen an overheated economy.

Parenteau’s frustration with Krugman is the latter’s systematic attacks on anyone to the left of him who understands the limits of the ISLM. Which limits have been demonstrated these last 7 years to favor creditor, corporate and other wealthy private interest at the expense of all the actual humans who must live under that systems constraints as the goal of surpluses drains the possibility of incomes out of the macro system.

Now this is what the article should have been.

One of my greatest frustrations in life is how Keynes is bastardized by both his detractors and those who purport to believe in him. As you rightly point out, Keynes recognized the nature of fiscal deficits, and his primary focus on cyclical balances was with regard to trade.

In 2008/09 when suddenly everyone was “Keynesian” they all overlooked trade rebalancing as being the primary point, and instead the fiscal stimulus exacerbated the macro imbalances. Well we see how that’s turning out!

As someone commented above, Keynes also respected limits to growth and therefore the end of growth capitalism…something that Krugman explicitly denies.

But the article was written so sloppily that all of this is lost and makes it sound like Krugman is against fiscal stimulus.

Mikkel: Here is some more sloppy analysis, where the framework of sectoral financial balances you are alluding to, but which most macroeconomists and policy makers remain painfully unable to grasp, is here.http://www.levyinstitute.org/pubs/pn_15_1.pdf

And I agree on your point regarding limits to growth and think that is a very good reason why any fiscal stimulus should be heavily oriented towards environmental remediation and shifting the nation to a much more robust renewable energy basis as rapidly as possible, because the private marketplace is not getting us there fast enough, judging by the third year of drought going on where I live. Bob Pollin at UMass Amherst writes a lot on all of that – go take a look.

I’m glad this got mentioned – the environment. There is an entirely new economy waiting out there and capable of absorbing every dollar we can print. It can match the value of every dollar all the way to infinity. Our understanding of money has reached the end of an era, and if we weren’t so afraid of change we could get started on a new reality right away. I think we should forget all about efficiencies and productivity for profit (unless that profit gets plowed back into labor intensive ecological pursuits like new age sustainable, healthy farming….) If we can’t get out of the profit ratrace it will be our nemesis. It already is. And the tragedy is that there are more good environmental jobs out there, worldwide, than we can fill in 50 years. Yes, it will probably make modern finance look quaint. But it is.

jsn: You are quite right on all of that, and there is a lot you could teach Paul, if you could only just convince him these were all his ideas first…and he wrote about them in a 1998 BPEA paper….Seriously. That is the Keynes/Kalecki/Lerner/Minsky framework that is missing…or has been “disappeared”, as they used to say in Chile in 1973. And in its place, we have clowns, albeit Very Serious Clowns, seated in Very Serious Positions, who try to pass themselves off as New Keynesians, when they have little or nothing to do with Keynes, but maybe have something to do with Milton Friedman the monetarist, or Irving Fisher the real interest rate guy, at least before he lost his house and his fortune in the Great Depression and did a major rethink on the self-equilibrating tendencies of modern capitalist economies. It is twisted. Really twisted. But hey, Kudlow is on TV everyday, so I guess anything is possible when you go through the Looking Glass.

I agree with what others have said: Krugman is in favor of fiscal measures in the current situation. Maybe for the wrong reasons (ZLB and IS/LM), but still.

Please provide links as to where he has said that. In the deficit debates, he called ONLY for continued deficits now, not for an increase in spending, AND he clearly endorsed the idea of getting to balanced budgets longer term.

See this comment as to why this is bad policy:

http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/03/robert-parenteau-the-large-fly-in-krugmans-new-keynesian-soup.html#comment-2413122

More recently, Krugman has endorsed extreme monetary measures and has not been calling for more fiscal stimulus.

I’m not out to defend Krugman, but there is a rather low ratio of analysis to invective in this post. Regarding the chart, the chief problem here is endogeneity. As we all know, during buoyant economic times the demand for funds generally rises, putting upward pressure on real interest rates. Using a lagged moving average for r will not necessarily eliminate this. One should also take into account the effects of fiscal policy on both real interest rates and growth. The effectiveness of interest rate policy (I prefer this term to monetary policy in a world of endogenous money) can be determined only by controlling, so far as one can, for other confounding factors, including case study evidence.

I agree, however, with the criticism that New Keynesians are willing to countenance stimulative fiscal policy only in circumstances in which interest rate policy loses traction (liquidity trap) and not more generally as they should. This view is based on arguments that have little to do with the claim that interest rate policy is normally ineffective.

Yes, Peter, you are right, the analytics and econometrics her are rather simple minded. We both know you can do all sorts of econometric tweaking and theoretical hemming and hawing, and yes, that is what economists do, though unfortunately, it is a rare day that any of the econometrics seem to settle these issues. Let’s instead ask ourselves, what is the story we are telling ourselves, that Krugman is telling us, and that central banks want us to believe? The story is also simple: if we lower real interest rates, one way or another, we will get out of liquidity traps and secular stagnation traps, and we will get back to full employment growth paths, and we will do so without having to worry about ever escalating public debt to GDP ratios, which we are told all the time will either lead to the hell of hyperinflation or some other form of economic collapse…even though we seem to have this little problem with headline CPI deflation creeping into nation after nation over the past year or so. And we are also told if we do in fact take this lower real interest rate medicine, that any recovery might take time – Paul was talking 15 years or something in Japan at 4% inflation as his back of the envelope guesstimate in 1998 to close the output gap in Japan. Yeah, that is right – 15 years. Seriously, skim the paper. And what does the chart from Goldman Sachs et al tell us? In the long run, there is not much of a relationship between real interest rates, specifically real policy rates, and real GDP growth. I am not talking causation here. I am just talking correlation. What does the connection look like – forget what the theory tells me it should look like. Read the Hatzius paper if you want the actual correlation coefficients – there answer is roughly, it depends, but it looks like a small positive correlation to them. Now after all the pissing and moaning that mainstream economists have made about discretionary fiscal policy and recognition lags and fine tuning, lets agree to agree with them. Yup, it is the long run that matters, and these liquidity traps and secular stagnation traps, yup, they might just be long run problems that we need long run policy measures to address. And so in the long run, what do we see, and what do Hatzius’ et al’s econometrics tell us? Real interest rates, specifically, real policy rates, do not seem to matter much to actually, observed real GDP growth outcomes.The earth of real GDP growth does not appear to revolve around the sun of real interest rate levels. Hasn’t done so for a 145 years or so. And has not done so across a dozen nations over the length of Paul’s professional career. It just ain’t happening. But that is what are supposed to believe. And if there is no relationship in the long run, why should we believe there is one for the short run? I am sure someone can rig the econometrics up to show one. (Oh wait, dig out your Taylor Rule equations). Let them. Then Hatzius can write the rejoinder.

Look, we are running enough live experiments on the effectiveness of negative real, and now negative nominal interest rates as well, each with various degrees of financial tightening and in some cases, for short times, fiscal loosening. How are they working out? In the US we have the lowest mortgage rates since WWII or maybe the Great Depression. Corporations have record high profit margins and face record low borrowing costs. Plot the investment share of GDP for the private sector, leaving out inventories and government investment . Pretty low, right. Not much of a lift from the lows of 2008/9, right? In fact, basically back to an investment share that we normally see at the bottom of prior post war recessions. Or ask PM Abe how he feels about the effectiveness of negative real rates after he puts up the consumption tax to save Japan from a higher public debt to GDP ratio? Ask the people of Greece and Spain and Portugal how they feel about Draghi’s negative nominal deposit rate and TLTRO or the imminent unleashing of QE? They’ll say, what are you talking about, my son just overdosed, he couldn’t find work, and I read in the paper the youth unemployment rate is 50%. So please, yes, go do much more sophisticated econometric work on the relationship between real GDP and real interest rates, and yes, please tweak the theory and hash it out all out very elegantly and oh so complexly, but let us not lose sight of what is at stake here, and what is working and not working, in the world that we are actually inhabiting. Please. I mean that sincerely, Peter.

You remind me of a classic scene from Good Morning Viet Nam:

Cronauer: Now, here’s the weather, we’re going to go right to Roosevelt E. Roosevelt. Roosevelt, how’s it goin’?

Funny voice: Adrian, I’m with somebody! Don’t ever come here and bother me right now!

Cronauer: Well thanks, Roosevelt. Can’t you give us a little weather?

Funny voice: Not now, man! I’m on the balcony, man, I’m tryin’ to score! Back off!!

Cronauer: Well, what’s the weather like?

Funny voice: You got a window? OPEN IT!

Economists really have get out more often. Like Yogi Berra said, “You can observe a lot by just watching.”

Just for the record, Larry Kudlow is owned and operated by the CIA.

Why do you say that? What makes this hack any different than all the others?

There is no doubt that interest rates can affect economic activity, especially at the extremes. But a business man will invest in a project, not depending on the interest rate, but his expected profit. And high interest rates may have little effect to tame inflation caused by supply shocks like shortages of food, oil or available labor. Just ask Volcker.

The federal government with a freely floating fiat currency can control the economy and maintain full employment and price stability. And this can be done through spending and taxing. So far as I know no one has ever shown such a government can be forced into involuntary insolvency. So the debt to gdp ratio is so much nonsense. ( and to hell with Rogoff, and his idiot friend,) Bonds may be useful to control interest rates but aside from that, there is no need to issue them. Heck the government creates money from thin air to buy them back in QE or spends trillions to bail out banks.

Krugman seems to discover these truths as needed. So he is useful, perhaps not the idiot like Kudlow.

The author is writing about some other krugman.

Krugman is not an mmt guy, but he has continuously called for lots more fiscal stimulus at least since 2008.

And he has politely dissed rogoff etc….

For that matter, fed also has quietly and continuously called for fiscal stimulus, too…

Granted they don’t appreciate qe is counterproductive, but even here must remember this was aimed at saving banks, not economy.

The problem bringing back the economy is austerity focus in congress/administration/general public, and the never ending wet dreams of a balanced budget amendment that will bring endless prosperity (a la European experiment), as discussed today by Mitchell.

Please provide links on the “calling for more fiscal stimulus” since 2011.

In the deficit debates, he was against reducing the deficit now, which is not the same as calling for more spending, AND he endorsed the idea of balancing the budget longer term.

what this tells me is real interest rates have to be -1.75% to really work.

anything else and your just guessing!

They are, and everything is fine.

I don’t know why there’s a compulsion to make this complicated.

People can never just agree on things.

“New Keynesians like Krugman, Bernanke, Blinder, Yellen, etc. believe they have found a hammer, namely Irving Fisher’s real interest rate hammer, and so the whole economic world looks like a nail to them. Got an unemployment problem? Lower real interest rates. Got an inflation problem? Raise real interest rates. Life is simple, and life is good. It’s all there in Krugman’s 1998 paper – seriously, skim that piece.

In that world, we are encouraged to forget about fiscal policy – government debt to GDP ratios are too high already – just ask Reinhart and Rogoff – and so few developed markets nations have the policy “space” to use fiscal stimulus, ever again, apparently. Even if they have sovereign currencies. Instead, monetary policy is deemed hegemonic.

And by the way, now that even central banks like the ECB are doing QE, monetary policy is fiscal policy. It is just that rather than using money to produce something useful and increase household incomes, which is what fiscal policy usually does, and is so unfashionable, money is being used to produce capital gains for bondholders, and maybe even equity holders as well, if the portfolio balance channels are not too clogged. The only problem seems to be that bond and equity holdings are highly concentrated in the highest reaches of the income distribution, so this is just trickle down economics in New Keynesian drag.”

Factually incorrect. Bernanke regularly testified that austerity was hurting. Krugman writes about the harms of austerity and the need for fiscal stimulus. Even Larry Summers is calling for government spending.

Europe is finally resorting to QE because they have to. Meanwhile the U.S. is doing well enough to consider raising rates. Naked Capitalism: always making the perfect the enemy of the good.

Yes, if you think neoliberalism is a good. If on the other hand you’ve noticed it has impoverished people systematically these last 35 years, maybe being its enemy looks a little different.

https://thecurrentmoment.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/productivity-and-real-wages.jpg

QE isn’t about helping the economy, it’s about transferring wealth to the highest percentile. That’s what it’s always been about.

Also, helping the economy (like GDP growth, albeit tepid) does not necessarily help those who want to avoid starvation.

There is a way to salvation though – that is, new money created to go directly, immediately to the people.

It’s the People’s Monetary Policy (PMP).

Some call it heterodox MMT or HMMT, or MMT II, i.e. MMTII.

Jack – I live in a distinctly middle class neighborhood in Phoenix and my home would likely sell for about a two week time share in NYC. My neighbor owns a company that modifies the interiors of private jets. I saw him driving by in his Bentley recently and he stopped so we could chat (I’m not making this up!) I asked how business was. “Terrific”, he replied,”never better”. So, please don’t say that there has been nothing more than a transfer of wealth to the to the highest percentile. Some is indeed making its way to us regular folks. My model predicts, if things keep trickling down like they are now, most of the folks still lucky enough to be alive 50 years from now will be doing fairly well.

Yes Peter, if you think neoliberalism is good. If, however, you’ve noticed it impoverishing the middle class these last 40 years, https://thecurrentmoment.files.wordpress.com/2011/08/productivity-and-real-wages.jpg , you may see it differently.

Huh? Bernanke was calling for reducing the deficit in 2010 in Congressional testimony, just not right away:

I think it’s fair to say that deficits, structural deficits, longer-term deficits, at anywhere between 4 and 9 percent, anywhere in that range, is not sustainable because it leads to a debt-to-GDP ratio that grows essentially indefinitely and does not stabilize, which leads to higher interest rate payments which in turn feed back into the deficit. So I think it’s very important that we consider how, looking forward — not this year, because of many economic conditions that are moving toward higher spending and lower revenues — but over the medium term as we try to plan our fiscal policy going forward, we need to find a sustainable path, and that would require lower deficits than we are currently projecting, or at least CBO is projecting.

http://reason.com/blog/2010/04/15/bernanke-give-me-balanced-budg

And again in 2012, just not immediately:

http://www.ozarksfirst.com/story/d/story/bernanke-urges-house-budget-committee-to-find-bala/40986/YZ0K6EbBcECWId1eKGhR3A

When will you stop making stuff up?

I generally agree about the silliness of focusing on monetary policy and interest rates and wish Krugman would be a bit more radical with the perch he has carved out. But it seems a little odd to so forcefully go after somebody who has been one of the most vocal establishment voices in favor of fiscal policy.

What I find most interesting is this little aside (my bold):

The word usually strikes me as a revealing generalization about the mindset taken by the author toward government power broadly and spending specifically, especially in the US context. Most of the federal budget activity impacts four specific areas of our society:

1) national security

2) healthcare security

3) income security

4) indirect regulation (like mortgage guarantees, unfunded public school and employer mandates, non-dischargability of higher ed debt, ag subsidies, and the hodge podge of tax cuts, deductions, exemptions and loopholes that have eaten away at progressive income taxation)

To make a claim that this money is generally producing something useful requires actually evaluating these programs. There is a very real case to be made that none of those four categories are too small. 1 and 4 in fact could be argued to be way too big, while a critique of 2 and 3 could suggest they aren’t so much an issue of size as poor allocation.

And linking making something useful with increasing household income makes no sense. Household income is also increased when government spends money on things that are not useful. (That’s the whole point. A dollar is a dollar no matter who receives it, whether it goes to the multi-millionaire CEO of a hospital franchise or the housekeeping staff making subsistence level wages. This is just basic math and accounting. Holding net exports and private sector investments constant, an increase in public sector deficits increases private sector savings no matter what kind of spending the public sector does.)

I cannot tell you how much it warms the cockles of my heart to see so many of you defending Paul’s support for fiscal policy as an effective and useful policy tool, especially when it comes to liquidity trap situations. But you, my dear readers, have been punked. There is Paul Krugman the NY Times columnist, and there is Paul Krugman, the MIT trained wunderkind, infant terrible economist…who actually is a monetarist, perhaps more of Irving Fisher’s Pre-Great Depression stripes than say Milton Friedman’s…and is not really a Keynesian, at least the Keynes we find after he shed many of his monetarist and Wicksellian skins from his writings in the 20s on his way to the General Theory…and if you allow him to do so, Paul would like to tell you that in his very own words, from the 1998 piece he believes we all need to seriously skim, but which apparently none of you have bothered to read, seriously or skim fully, before posting your comments. So hear we go – I will take you through his text step by step so we together do not miss a trick.

Lots of wonderful informed sophisticated snark out there, with carefully footnoted quotes and references, about this, that or the other pronouncement or model championed by this or that Leading Light of this or that economic school theory. These Serious People apparently drive “policy,” or at least provide a vanishingly thin patina of justification for the behaviors that get canonized as “policy,” or sit as back-benchers in the Opposition to offer their worldly, incisive and often funny cheers and jeers.

Can anyone offer links or directions to the works or writings of ANYone who is honest and holistic and sort of correct about the basic nature and predictable behaviors of all the participants and rulers and victims of what I guess is supposed to be “the economy,” or what I recall reading somewhere might have once been styled “political economy?” Krugman’s an egotist, and a self-promoter, and just wrong? Well, who the hell is RIGHT? if that word has any meaning down here in the slave pits?

C’mon — is it all just feckless, albeit trenchant and brilliant and well-spoken, sniping back and forth about “science” that is hardly scientific, and cannot predict or control anything, at least via any of the “wisdom” deemed mainstream? Or is it just TPTB unlimbering Bigger Notable Guns like the Named Greats and the successful gamers like Friedman and Bernanke and so forth who actually get to Move The Lever(s) of Interest Rates and stuff, while GINI goes south and ordinary people in places like Greece and Venezuela and Mississippi get increasingly impoverished while the world burns?

It seems to this lowly old person that NObody in the Game has an honest and accurate set of notions to offer, just sophisticated, inventive and often devious critiques of tiny closets of a very large house, and apologetics for whatever “policies” will advance their own wealth accumulation and position.

Maybe it’s inevitably thus, and we mopes, muppets and Dumb Money, those that still have any, just have to eat sh_t and die, preferably out of sight? Without regard to the survival of the species? That’s the nature of said species? (Of course, say the “successful…”)

If that’s the object of the Game, just to be “the one who dies with the most toys after killing the most others and taking their stuff,” at least be honest and tell the rest of us right out front. Makes one wonder why ISIS is so scary — they have a very successful business model: The Banality of Islamic State

How ISIS Corporatized Terror, http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2014-the-business-of-isis-spreadsheets-annual-reports-and-terror/#/ Just like General Motors and the M-style.

Marx, Keynes, MMT, ecological (not environmental) economics are all pretty useful and correct from their various perspectives.

What does that even mean? “From their various perspectives”? The old chestnut about the blind philosophers arguing about the true nature of the elephant, from having fondled just one part? The ” sell” on economics is that it’s predictive of how to move the levers and what gear to be in or something. Looks like nothing but post hoc rationalizations and a lot of arcane lingo. And please, what is the goal of the game? Everyone assumes that there is one, but if so, it looks a lot like accumulate, consume, and die, taking everything down with us. Justified by citations from one’s preferred “experts.”

p. 160 from Paul’s 1998 Opus on Everything You Ever Needed to Know about Liquidity Traps and Macroeconomics in General, linked here in case you need to verify any of this:http://www.brookings.edu/~/media/projects/bpea/1998%202/1998b_bpea_krugman_dominquez_rogoff.pdf

Here, Paul tells us the Great Depression was not ended by a one of fiscal stimulus, as many seem to think. What was the Great Depression ended by then, in the Gospel of Macro According to Paul. Read it. It says it depended on what? Fiscal policy? No. It was inflation expectations. Specifically, inflation expectations that MADE REAL INTEREST RATES SUBSTANTIALLY NEGATIVE. So really, it was negative real interest rates the ended the Depression. Got it?

“My point is that the end of the Depression, which is the usual, indeed perhaps the sole, motivating example for the view that a one-time fiscal stimulus can produce sustained recovery, does not actually appear to fit the story line too well. Much, though by no means all, of the recovery from that particular liquidity trap seems to have depended on inflation expectations that made real interest rates substantially negative.”

And all that is nowimpossible now because we have reached a level of technology that could (if it wanted to) balance our consumption… but if our consumption were maintained there can be no consensus to maintain it because none of us understands this balance … we are lacking in a certain spiritual containment…so we just can’t get a handle on it… So, the world ended?

The feudal critters have one process, extending RE credit in exchange for work with falling interest rates, and taking everything built with increasing interest rates, which is why they pretend to pay and most pretend to work, exploiting natural resources from the local community to feed the global city, more paper, until they can’t, and why you let them steal your second derivative, replacing automation with more efficient automation.

The empire is now dependent upon dc electronics, as a replacement for labor, which doesn’t work in the real world, surprise, because what they cannot see, the universe, is growing, and what they can see, their own self-fulfilling prophesy of infrastructure make-work, is shrinking. The planet is rotating, just not relative to what they are looking at, themselves in the mirror.

Yes, I’m one of the stupid ones, that moved Navy assets out and the university medical complex in, and the critters all think they are qualified to be my boss, because their parents told them so, and their teachers rewarded them for thinking so. Public education is about normalization, not learning. Feudalism has been kicking the can down the road accordingly for thousands of years.

Clinton or Bush, $20/barrel from ISIS, $200/barrel from Saudi, or $45/barrel from North America, makes no difference to labor. Pick something you find interesting and explore, and sooner or later the future will pass through you, and on to your children, leaving the empire behind to pay interest and penalties, on the arbitrary debt it created, to hunt you down.

For every force…the electron exists in many dimensions, and none at all. What Yellen, Pelosi and Brown do is irrelevant, to your future. Their job is to manage the past, the spoil pile of symptoms affecting symptoms, dressing the empire. Navy is much more than corrupt captains of global industry, the history of gravity, which is whatever you choose it to be.

Politicians in Greece and Germany are like an old married couple with no children, arguing about the future, of the nation/state in a box, always a damsel in distress, looking in the mirror and seeing the enemy, a zero-sum game. The assumption that labor works for capital is false, no mater how loud the empire screams. Be at that interview, regardless of misdirection thrown in your path, license or no license, black, white or pink.

they have tried shock and awe in both directions, creating economic activity in growing make-work, so now they are trying distillation/isolation.

careful, when you go looking for that electron, to exploit.

But let’s play fair here. Because also on p.160 of Paul’s Gospel, you will find this:

“If temporary fiscal stimulus does not jolt the economy out of the doldrums, however, a recovery strategy based on fiscal expansion would have to continue the stimulus over an extended period. Which raises the quantitative question of how much stimulus is needed, for how long-and whether the consequences in terms of government debt are acceptable.”

Ok, so Paul says you might need more than a fiscal quickie. But if it is going to be more than a quickie, honey, it is going to cost you. And it might cost you big. And who are you going to have to pay. Well. that depends upon who you are going to ask “whether the consequences in terms of government debt are acceptable.” Which would be your Big Daddy Bond God Pimps, cuz they demand risk premia on their interest payments, bitchez. And if you are going to go big, long, and hard on your fiscal stimulus, you be better be prepared to pay big and long and hard too.

You could tackle this one with specific advocacy and that would give us a reference point for future discussion.

What is your proposed budget for next year (for the USFG)? How about the next five years? I don’t mean to the penny, just a general idea of what you propose in dollar amounts for receipts and outlays.

Here is a link to the White House website for a variety of reports on budgets. For comparison, the President’s 2016 budget has about $4 trillion in outlays and $3.5 trillion in receipts.

http://www.whitehouse.gov/omb/budget/Historicals

But let’s clarify the Gospel of Paul a little further here, because he seems to have introduced a slight ambiguity – are we supposed to do fiscal for more than a quickie, or is it all about the real interest rate level at the end of the day. So far, it is no that obvious. But if we dig a little deeper into the Gospel of Paul, here is what we find on p. 178.

“There are two major questions about fiscal expansion as a remedy for Japan, one strictly economic, one political. The economic issue is whether an adequate expansion is possible without creating an unacceptable impact on the government’s long-term fiscal position.

If one expects interest rates to stay near zero indefinitely, the level of government debt hardly matters. But if one ex- pects that at a sufficiently distant date real rates will become strongly positive again, the eventual size of that debt becomes an important concern.”

Ok, the fog is lifting. If you chose to go big and long and hard on fiscal policy, it has to be “acceptable” in the long term. Acceptable to who, you might ask. Big Daddy Bond Pimps. Because the condition of acceptability of a prolonged fiscal orgy is all about the interest rates, once again. If they interest rates stay can be kept near zero in perpetuity, no problem, go for it. But hey, if you cannot sign on the dotted line with that one, you have no business going to the prolonged fiscal orgy room at this hotel. None. So you see, you cannot, by Paul’s own words, expect to do prolonged fiscal stimulus, unless and until you are prepared to get monetary policy to pin down zero interest rates. Forever. Fiscal policy is conditional upon monetary policy. Keynes is on a leash.

Funny that. So why not keep interest at zero or near there? Or better yet break the leash and just create money as you need it to maintain full employment?

Plus, remember, Paul noted there might be a prior constraint on doing the full Monty with Keynes’ fiscal stimulus. A constraint that show us before the monetary policy cum Big Pimping Bond Daddy one. That is the weenie constraint. Politicians might be weenies. Seriously. Read it yourself…and weep, all you closet Keynesian who are rising in Paul’s defense:

“The political point is that Japan – like the United States during the New Deal – appears to have great difficulty in working up political nerve for a fiscal package anywhere close to that required to close the output gap. Exactly why this is so is an interesting question, but beyond the paper’s scope…This surely does not, however, mean that fiscal policy should be ignored as part of the policy mix. On the general Brainard principle – when uncertain about the right model, throw a bit of everything at the problem – one would want to apply fiscal stimulus. (Not even I would trust myself to go for a purely Krugman solution)<e. But it seems unlikely that a mainly fiscal solution will be enough."

Read it again. Politicians can be weenies…but we aren't allowed to talk about why…though maybe it has something to do with the political interests of the Big Pimping Bond Daddies. So yeah, sure, do a little jig for Keynes, but dancing around a little with Keynes, Paul says, ain't enough. You need the Krugman Solution. That's right, you read it here first. THE KRUGMAN SOLUTION…AS IN, IT IS NOT THE SAME AS THE KEYNES SOLUTION…right there…in Paul's own hunting and pecking on his laptop. In the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. In his magnum opus. Seriously, you should skim this thing, like he told you to…but you didn't…because you already bought the labeling, and you know he's a New Keynesian, with the emphasis on Keynes. Who he just suggested you can dance with, and many take home for a hook up, but Jesus, Mary, and Joseph, do not under marry the bastard, unless Big Pimping Bond Daddy gives you the go ahead first, of course.

So what, pray tell, is the Krugman Solution? Well, Paul starts to spell this out a little further on the next page. He concludes, after analyzing the slack created in Japan from the liquidity trap:

“Therefore Japan probably requires a sustained period – at least a decade – of inflation, to reduce the real long term rate sufficiently to close the output gap…how about 4 percent inflation for fifteen years?”

The Krugman Solution is all about the level of the real long term interest rate you see. Why? Because that is what Paul is proposing to use to close the output gap. Yeah, you read that right. The output gap is to be closed not by fiscal policy. Not by Keynesian fiscal stimulus at all. The output gap is to be closed by lowering real interest rates, which as we will see in a moment, is largely the purview of monetary policy, and a monetary possible that is aimed at creating expectations of rising inflations. Fiscal policy might be considered for a little pump priming up front, subject to the zero interest rate is nailed firmly down by the central bank, a constraint he already discussed above, but the heavy lifting is all around getting inflation expectations up in order to get real interest rates down. And that’s Irving Fisher. Or Wicksell. But not so much Keynes, who thought interest rates would not quite be enough, at least by the time he got to the General Theory.

But are we sure about this primacy of interest rates and monetary policy in the Krugman Solution (sorry, is that trademarked yet Paul)? Are sure Paul wants the Bank of Japan, or for that matter, any central bank, to play the lead role in generating inflation expectations? Can’t you do that by closing the output gap with fiscal policy? Oh, wait, we closed that door. Because the Big Pimping Bond Daddies are behind it. Don’t go there. Don’t even go there. So the inflation expectations thingy, well, that is a subject that has more to do with social psychology, and we economists really don’t talk about such trite and trivial things as that, but if we have to talk about, we know exactly who we can call to get the job done. The central bank. The BoJ. Not the Treasury. Not the Congress. The central bank. Read on:

“If the central bank can credibly commit to pursue inflation where possible, and ratify inflation when it comes, it should be able to increase inflationary expectations despite the absence of any direct traction on the economy by means of current monetary policy.

How in fact to create these expectations is, in a sense, outside the usual boundaries of economics. However, one obvious suggestion is that Japan deal with its inverted credibility problem through legislation giving the Bank of Japan an inverted version of the price stability targets now in force in a number of countries”.

That is, in the Gospel of Paul, under the Krugman Solution, to get inflation expectations going, and then to validate them, you must “set my people free”. You’ve got get your legislative body to create an enforceable commitment from the central bank to pursue accelerating inflation at all costs, no holds barred. You do not go to your legislative body and create a credible commitment to a full employment fiscal policy. That would be too, well, Keynesian. Plus the Big Pimping Bond Daddy’s will tear you a new one if you do…unless of course the central bank has your back and is pinning the yield curve to zero, all the way out the curve. Are you listening, ECB? I knew you could – love me some Germany 5 year bunds, sub zero. Yeah, that’s what I am talking about baby, bring it on home to Momma, Mario.

This calls for a reading the “Keynesian” prayer, in honor of High Priest Krugman.

We must borrow more money,

To stimulate demand,

So that jobs are created,

And prosperity ensues,

Then we pay off our loans.

(Well, unless we don’t have enough prosperity. Which just means you haven’t prayed hard enough and borrowed enough).

Amen.

Two, three thousand years later, it will still be ‘if you are a believer in Paul the high priest and his good news, you will be saved and will have saved a great fortune for your family.”

I see you are still upset that reality has a Keynsian bias, NaRm. I await your policy/economic suggestions for wealth inequality, wage stagnation, and erosion of democracy with bated breath…

But wait, are we sure Paul is determined to put real interest rates as the main adjustment mechanism, and not fiscal stimulus? Are we sure he want monetary policy to carry the ball on this? Paul tries to get a little more granular with the Krugman Solution on p. 181. Seriously. Don’t just take a leap of faith. Skim this thing.

“I would suggest the following series of leaps of faith: although Japan’s current output gap is probably well over 5 percent, the combination of fiscal stimulus and – if all goes well – clarification of which banks will be taken over and which will not, should reduce the gap by several percentage points. Therefore managed inflation would need to close a remaining gap of, say, 4 to 5 percentage points. …Recall that a policy of managed inflation is, in principle, simply a monetary expansion by other means.”

Ok, so let’s do the math with Paul. Because, you know, economists are pretty good with math. Japan had an output gap of 5% of GDP when Paul did his back of the envelope calculations in 1998. That is a lot of slack. There is a big gap between potential output and actual output in Japan. This is going to take some heavy lifting. So let’s get to it. Yeah, ok, let’s have fiscal policy give it a go, and then let’s use the Krugman solution of managed inflation to close say 4-5%…of a 5% output gap. Wait, what? Do the math. Managed inflation, which is “SIMPLY A MONETARY EXPANSION BY OTHER MEANS”, is assigned to handle cover 4% or 5% of what is only a 5% output gap…which means fiscal stimulus will be tackling 0-1%. Yup. There it is. See. Paul is a Keynesian. A devout, frothing at the mouth Keynesian. Not a Monetarist. A Keynesian. Repeat it enough times. You might even to be able to make yourself believe it. Seriously. Skim this piece and you’ll see why I sometimes seem so frustrated. Just like Paul. Except even more so. Because he’s punked you, dear readers, into thinking he is a frothing at the mouth Keynesian. Well, only if the Big Pimping Bond Daddies don’t come around, maybe he is, but really, we can settle 80-100% of the problem just through the central bank. Using real interest rates. Which appear to have no inverse correlation with real GDP growth. According to a Goldman Sachs economist, and one of the few Wall Street economist I still respect, because he won’t do a Kudlow…nor will he do a Kruggie either.

Actually, I didn’t know Kudlow was an economist. I always thought he was a comic.

what’s the difference?

Comics are much cheaper.

that’s one of the things that makes economists so funny.

‘Cept they’ll have you laughing all the way to the poor house.

See, I just did it. There are no neo-poor houses anymore.

A mission accomplished economist will make you cry (at least the neoliberal kind) over your misfortune, while a good comic will make you laugh at the same.

That’s my best guess.

Let’s now close out our exegesis of the Gospel of Paul with the closing argument from Appendix C, appropriately entitled Creating Inflation Expectations, which after all, is at the heart of the Krugman Solution. Here, in summarizing the entire screed, we read the following: