By Arthur Berman, a petroleum geologist with 36 years of oil and gas industry experience. He is an expert on U.S. shale plays and is currently consulting for several E&P companies and capital groups in the energy sector. Berman is an associate editor of the American Association of Petroleum Geologists Bulletin, and was a managing editor and frequent contributor to theoildrum.com. He is a Director of the Association for the Study of Peak Oil, and has served on the boards of directors of The Houston Geological Society and The Society of Independent Professional Earth Scientists. Originally published at OilPrice

The U.S. oil production decline has begun.

It is not because of decreased rig count. It is because cash flow at current oil prices is too low to complete most wells being drilled.

The implications are profound. Production will decline by several hundred thousand barrels per day before the effect of reduced rig count is fully seen. Unless oil prices rebound above $75 or $85 per barrel, the rig count won’t matter because there will not be enough money to complete more wells than are being completed today.

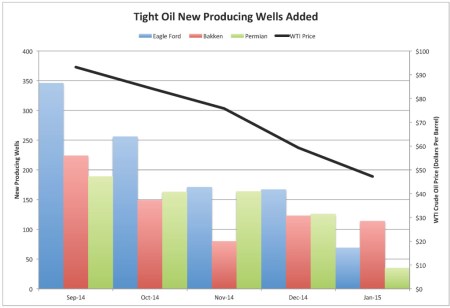

Tight oil production in the Eagle Ford, Bakken and Permian basin plays declined approximately 111,000 barrels of oil per day in January. These declines are part of a systematic decrease in the number of new producing wells added since oil prices fell below $90 per barrel in October 2014 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Eagle Ford, Bakken and Permian basin new producing wells by month. Source: Drilling Info and Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc

(Click image to enlarge)

Deferred completions (drilled uncompleted wells) are not discretionary for most companies. Producers entered into long-term rig contracts assuming at least $90 oil prices. Lower prices result in substantially reduced cash flows. Capital is only available to fulfill contractual drilling commitments, basic costs of doing business, and to complete the best wells that come closest to breaking even at present oil prices.

Much of the new capital from junk bonds and share offerings is being used to pay overhead and interest expense, and to pay down debt to avoid triggering loan covenant thresholds. Hedges help soften the blow of low oil prices for some companies but not enough to carry on business as usual when it comes to well completions.

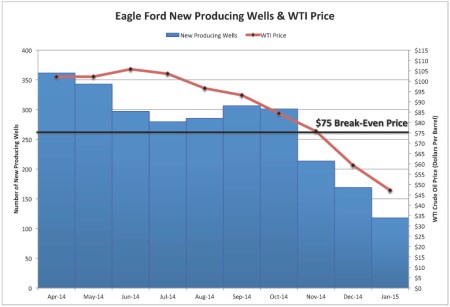

The decrease in well completions provides additional evidence that the true break-even price for tight oil plays is between $75 and $85 per barrel. The Eagle Ford Shale is the most attractive play with a break-even price of about $75 per barrel. Well completions averaged 312 per month from January through September 2014 when WTI averaged $100 per barrel (Figure 2). When oil prices dropped below $90 per barrel in October, November well completions fell to 214. As prices fell further, 169 new producing wells were added in December and only 118 in January.

Figure 2. Eagle Ford new producing wells (2 month moving average) and WTI oil prices. Source: Drilling Info, EIA and Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

(Click image to enlarge)

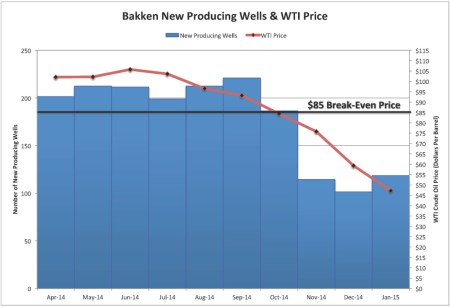

Bakken break-even prices are higher at about $85 per barrel. Well completions averaged 189 per month from January through September 2014. In November, only 80 new producing wells were added. In December and January, 123 and 114 new wells were added, respectively. Orders for rail cars used to transport oil decreased by 70% in the first quarter of 2015 compared with the fourth quarter of 2014.

Figure 3. Bakken new producing wells (2 month moving average) and WTI oil prices. Source: Drilling Info, EIA and Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

(Click image to enlarge)

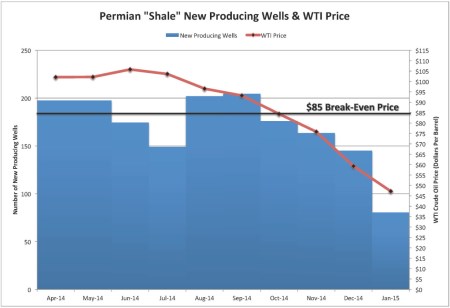

Permian “shale” play break-even prices are also about $85 per barrel based on declining well completion data. Well completions averaged 175 per month from January through September 2014. In January 2015, only 35 new producing wells were added.

Figure 4. Permian “shale” new producing wells (2 month moving average) and WTI oil prices. Permian “shale” includes horizontal wells in the Bone Springs, Consolidated, Delaware, Spraberry, Wolfcamp,Trend Area and related combinations of those reservoirs. Source: Drilling Info, EIA and Labyrinth Consulting Services, Inc.

(Click image to enlarge)

Much of the commentary about the backlog of deferred completions is exaggerated and irrelevant unless oil prices increase to $75 or $85 per barrel. The assumption underlying most industry chatter these days is that oil prices will return to normal.

The world oil market is undergoing a fundamental structural change in response to expensive oil. Producers are trying to survive by limiting expenditures. While analysts have been focused on rig counts, deferred completions have emerged as the initial path to lower U.S. oil production. This unanticipated outcome suggests that others may follow. While everyone is waiting for higher oil prices and for things to return to normal, what we may be witnessing is the end of normal*.

*James Kenneth Galbraith, The End of Normal–The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth (2014).

The fundamental question about the “oil sector” is one of the rate at which progress in extraction and refining techniques will improve estimates of “reserves.” Fossil fuels won’t last forever, but the date of “peak oil” always seems to be subject to brief postponements.

And then there’s this other question of climate change. What good is the ability to fill your gas tank if planetary ecosystems are screwed? Even with “declining reserves” it’s still true that survival depends upon keeping some of that black stuff in the ground.

. . . still true that survival depends upon keeping some of that black stuff in the ground.

When I put on my batshit crazy hat, that is THE reason why the Saudis want to get rid of their oil as fast as possible. Could there be a CO2 war in the future, where burning oil or coal is grounds for scrambling the useless F35?

When I take off my batshit crazy hat, none of that could possibly happen with all the rational people in the world.

Actually solar is improving so quickly that economics alone may shut-in fossil fuel production. Currently coal is most at risk, because natural gas and oil are mostly used for things solar is not so good at. Nonetheless, improvements in battery technology could put oil at risk. Even if the economics alone don’t do it, the reduced cost of renewables makes political action to shut down fossil fuel use more feasible as well.

It’s not *guaranteed* that economics will largely end FF use by any stretch, but it’s looking possible, and for actors with long planning horizons like the Saudis that can justify current action.

The kind of war you’re thinking about is possible too. China has an enormous area and population at risk from sea level rise. What happens to Shanghai in particular is very sobering.

Tesla’s announcement of a ‘home battery’ may make solar even more attractive to home owners.

Oil and coal are not at risk, and those who hope for “alternative energy” to save capitalism are fooling themselves with their own advertising rhetoric. Please read this diary:

http://www.dailykos.com/story/2014/08/10/1320160/-Will-alternative-energy-save-capitalism

All alternative energy sources are really only fossil fuel extenders. Think of the development, manufacture, operation, and maintenance of a solar or wind device. All employees get to their place of work via FF. All incoming shipments arrive via FF, all outgoing shipments take place via FF. All of the supporting infrastructure is built, operated, and maintained by FF. All of the services supplied to all of the primary participants are all enabled by FF. It is an infinite regression of absolute dependency on FF. If we were smart we would use the extension provided by alternative energy sources to plan and build for a low energy future. But sadly, this will not happen. We will keep doubling down on growth, “progress”, high energy trinkets, toys, and lifestyles.

In the near future, depending on how fast and how bad things get, burning fossil fuels will be illegal for most purposes, and probably unnecessary anyway.

I think you’re right.

Now where do I get my hat?

(to cnchall)

i have been under the impression that US oil production had been increasing up until mid-March…this is the EIA data i’ve been checking weekly: http://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/hist/LeafHandler.ashx?n=PET&s=WCRFPUS2&f=W

it’s been trending up 15% YoY..

can someone explain why it differs so much from the data cited by Berman above?

It’s easy to explain. This government lies ALL of the time.

Berman is talking about number of wells. If, for example, a large number of inefficient, low producing wells are replaced by a small number of efficient, higher producing wells, the number of wells will fall but oil production goes up.

The EIA graph shows production in barrels. The graphs above show new wells being drilled. They’re related, but strictly speaking different things. It takes a few months before changes in wells drilled shakes out and affects production levels.

That’s the scary thing for me. We can always argue about policy, but from what I can glean US Government data from the 1890s into the 1970s was fundamentally sound. That started to change subtly and at the margins under Johnson and Nixon and then massively under Reagan. The notion under Reagan was that if we don’t pay for EPA inspectors we can’t find any unwanted data, that ketchup was a vegetable, and that no matter what the Department of Energy, the Pentagon, and NOAA tells us nuclear winter is a pinko invention dreamed up to “stay our hand.” It was under Reagan that we started to substitute lies and wishful thinking for reliable data (think tinkering with the way we count the unemployed). The question before Reagan became president was normally, “what do we do given the data we see?” After Reagan, the question was “how do we tinker with or subvert the data to make it say what we want it to say?”.

Corruption of science as well (via manipulating research funding).

So the Saudis say they are not engaging in a price war, they are engaging in a credit war. Whatever. The difference seems to be a subtle way of saying that we are in a depression now compared to the economies of yesterday, growth is a distant mirage, and so price wars are pointless, but a credit war will normalize oil to a no growth world. In that world there is only room for the most efficient producer. We are left to assume that the oil industry may never raise its barrel price again because there will never be a growing economy. Which is good news for the environment. The reason people, like the writer here, do not put too fine a point on it is because fundamental change puts us all on the edge of panic. But even panic is changing “fundamentally” because there’s no place to run.

A quick search turned up nothing definitive, but I would guess that the drop in prices is having a similar effect on Athabasca tar sands production. Does anyone know about this beyond a reasonable doubt?