Yves here. Over the years, we’ve regularly criticized economists like Bernanke and Krugman, who rely on the so-called loanable funds model, which sees banks as conduits of funds from savers to borrowers. Despite the fact that many central banks, such as the Bank of England, have stressed that that’s not how banks actually work (banks create loans, which then produce the related deposit), central banks still cling to their hoary old framework. For instance, when I saw Janet Yellen speak at an Institute of New Economic Thinking conference in May, she cringe-makingly mentioned how banks channel scarce savings to investments.

Even worse, the macroeconomic models used by central banks incorporate the loanable funds point of view. This article describes what happens when you use a more realistic model of the financial system. Even though the paper is a bit stuffy, the results are clear: economies aren’t self-correcting as the traditional view would have you believe but have boom/bust cycles (the term of art is “procyclical”) and banks show the effects of policy changes much more rapidly.

Other economists who have been working to develop models that reflect the workings of the financial sector more accurately, like Steve Keen, have come to similar conclusions: that the current mainstream models, which serve as the basis for policy, present a fairy-tale story of economies that right themselves on their own, when in fact loans play a major, direct role in creating instability. It’s not an exaggeration to depict the continued reliance on known-to-be-fatally-flawed tools as malpractice.

By Zoltan Jakab, Senior Economist at the Research Department, IMF, and Michael Kumhof, Senior Research Advisor at the Research Hub, Bank of England. Originally published at VoxEU

Problems in the banking sector played a seriously damaging role in the Great Recession. In fact, they continue to. This column argues that macroeconomic models were unable to explain the interaction between banks and the macro economy. The problem lies with thinking that banks create loans out of existing resources. Instead, they create new money in the form of loans. Macroeconomists need to reflect this in their models.

Problems in the banking sector played a critical role in triggering and prolonging the Great Recession. Unfortunately, macroeconomic models were initially not ready to provide much support in thinking about the interaction of banks with the macro economy. This has now changed.

However, there remain many unresolved issues (Adrian et al. 2013) including:

• The reasons for the extremely large changes to (and co-movements of) bank assets and bank debt;• • The extent to which the banking sector triggers or amplifies financial and business cycles; and

• The extent to which monetary and macro-prudential policies should lean against the wind in financial markets.

New Research

In our new work, we argue that many of these unresolved issues can be traced back to the fact that virtually all of the newly developed models are based on the highly misleading ‘intermediation of loanable funds’ theory of banking (Jakab and Kumhof 2015). We argue instead that the correct framework is ‘money creation’ theory.

In the intermediation of loanable funds model, bank loans represent the intermediation of real savings, or loanable funds, between non-bank savers and non-bank borrowers;

Lending starts with banks collecting deposits of real resources from savers and ends with the lending of those resources to borrowers. The problem with this view is that, in the real world, there are no pre-existing loanable funds, and intermediation of loanable funds-type institutions – which really amount to barter intermediaries in this approach – do not exist.

The key function of banks is the provision of financing, meaning the creation of new monetary purchasing power through loans, for a single agent that is both borrower and depositor.

Specifically, whenever a bank makes a new loan to a non-bank (‘customer X’), it creates a new loan entry in the name of customer X on the asset side of its balance sheet, and it simultaneously creates a new and equal-sized deposit entry, also in the name of customer X, on the liability side of its balance sheet.

The bank therefore creates its own funding, deposits, through lending. It does so through a pure bookkeeping transaction that involves no real resources, and that acquires its economic significance through the fact that bank deposits are any modern economy’s generally accepted medium of exchange.

The real challenge

This money creation function of banks has been repeatedly described in publications of the world’s leading central banks (see McLeay et al. 2014a for an excellent summary). Our paper provides a comprehensive list of supporting citations and detailed explanations based on real-world balance sheet mechanics as to why intermediation of loanable funds-type institutions cannot possibly exist in the real world. What has been much more challenging, however, is the incorporation of these insights into macroeconomic models.

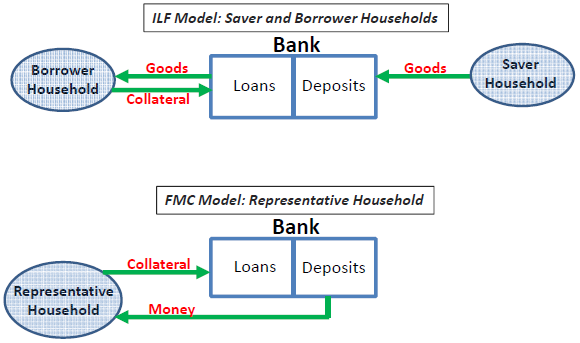

Our paper therefore builds examples of dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models with money creation banks, and then contrasts their predictions with those of otherwise identical money creation models. Figure 1 shows the simplest possible case of a money creation model, where banks interact with a single representative household. More elaborate money creation model setups with multiple agents are possible, and one of them is studied in the paper.

Figure 1.

The main reason for using money creation models is therefore that they correctly represent the function of banks. But in addition, the empirical predictions of the money creation model are qualitatively much more in line with the data than those of the intermediation of loanable funds model. The data, as documented in our paper, show large jumps in bank lending, pro- or acyclical bank leverage, and quantity rationing of credit during downturns. The model simulations in our paper show that, compared to intermediation of loanable funds models, and following identical shocks, money creation models predict changes in bank lending that are far larger, happen much faster, and have much larger effects on the real economy. Compared to intermediation of loanable funds models, money creation models also predict pro- or acyclical rather than countercyclical bank leverage, and an important role for quantity rationing of credit, rather than an almost exclusive reliance on price rationing, in response to contractionary shocks.

The fundamental reason for these differences is that savings in the intermediation of loanable funds model of banking need to be accumulated through a process of either producing additional resources or foregoing consumption of existing resources, a physical process that by its very nature is gradual and slow. On the other hand, money creation banks that create purchasing power can technically do so instantaneously, because the process does not involve physical resources, but rather the creation of money through the simultaneous expansion of both sides of banks’ balance sheets. While money is essential to facilitating purchases and sales of real resources outside the banking system, it is not itself a physical resource, and can be created at near zero cost.

The fact that banks technically face no limits to instantaneously increasing the stocks of loans and deposits does not, of course, mean that they do not face other limits to doing so. But the most important limit, especially during the boom periods of financial cycles when all banks simultaneously decide to lend more, is their own assessment of the implications of new lending for their profitability and solvency. By contrast, and contrary to the deposit multiplier view of banking, the availability of central bank reserves does not constitute a limit to lending and deposit creation. This, again, has been repeatedly stated in publications of the world’s leading central banks.

Another potential limit is that the agents that receive payment using the newly created money may wish to use it to repay an outstanding bank loan, thereby quickly extinguishing the money and the loan. This point goes back to Tobin (1963). The model-based analysis in our paper shows that there are several fallacies in Tobin’s argument. Most importantly, higher money balances created for one set of agents tend to stimulate greater aggregate economic activity, which in turn increases the money demand of all households.

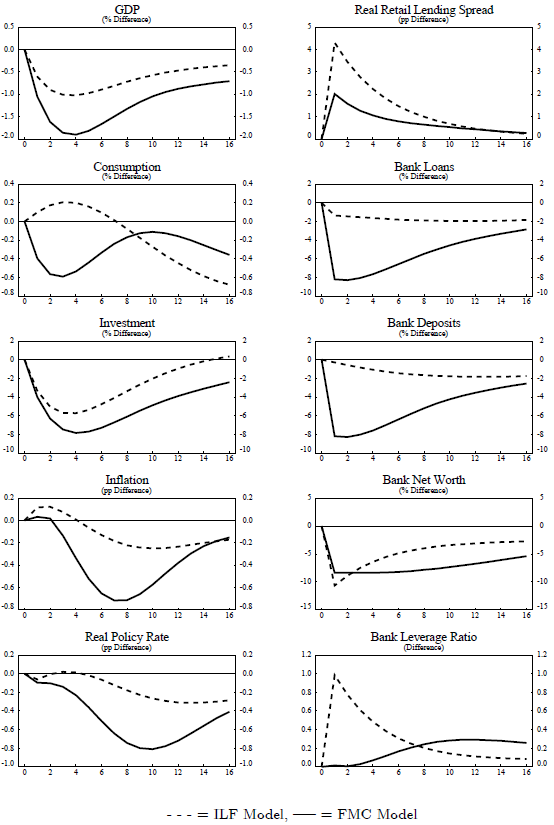

Figure 2 shows impulse responses for a shock whereby, in a single quarter, the standard deviation of borrower riskiness increases by 25%. This is the same shock that is prominent in the work of Christiano et al. (2014). Banks’ profitability immediately following this shock is significantly worse at their existing balance sheet and pricing structure. They therefore respond through a combination of higher lending spreads and lower lending volumes. However, intermediation of loanable funds banks and money creation banks choose very different combinations.

Figure 2. Credit crash due to higher borrower riskiness

Intermediation of loanable funds banks cannot quickly change their lending volume. Because deposits are savings, and the stock of savings is a predetermined variable, deposits can only decline gradually over time, mainly by depositors increasing their consumption or reducing their labour supply. Banks therefore keep lending to borrowers that have become much riskier, and to compensate for this they increase their lending spread, by over 400 basis points on impact.

Money creation banks on the other hand can instantaneously and massively change their lending volume, because in this model the stocks of deposits and loans are jump variables. In Figure 2 we observe a large and discrete drop in the size of banks’ balance sheet, of around 8% on impact in a single quarter (with almost no initial change in the intermediation of loanable funds model), as deposits and loans shrink simultaneously. Because, everything remaining the same, this cutback in lending reduces borrowers’ loan-to-value ratios and therefore the riskiness of the remaining loans, banks only increase their lending spread by around 200 basis points on impact. A large part of their response, consistent with the data for many economies, is therefore in the form of quantity rationing rather than changes in spreads. This is also evident in the behaviour of bank leverage. In the intermediation of loanable funds model leverage increases on impact because immediate net worth losses dominate the gradual decrease in loans. In the money creation model leverage remains constant (and for smaller shocks it drops significantly), because the rapid decrease in lending matches (and for smaller shocks more than matches) the change in net worth. In other words, in the money creation model bank leverage is acyclical (or procyclical), while in the intermediation of loanable funds model it is countercyclical.

As for the effects on the real economy, the contraction in GDP in the money creation model is more than twice as large as in the intermediation of loanable funds model, as investment drops more strongly than in the intermediation of loanable funds model, and consumption decreases, while it increases in the intermediation of loanable funds model.

Banks are Not Intermediaries of Real Loanable Funds

To summarise, the key insight is that banks are not intermediaries of real loanable funds. Instead they provide financing through the creation of new monetary purchasing power for their borrowers. This involves the expansion or contraction of gross bookkeeping positions on bank balance sheets, rather than the channelling of real resources through banks. Replacing intermediation of loanable funds models with money creation models is therefore necessary simply in order to correctly represent the macroeconomic function of banks. But it also addresses several of the empirical problems of existing banking models.

This opens up an urgent and rich research agenda, including a reinvestigation of the contribution of financial shocks to business cycles, and of the quantitative effects of macroprudential policies.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of the institutions with which they are affiliated.

See original post for references

A model that ignores the equity requirement/limitation of bank-lending isn’t much of an improvement…

This quote from their post clarifies:

“The fact that banks technically face no limits to instantaneously increasing the stocks of loans and deposits does not, of course, mean that they do not face other limits to doing so.”

Or maybe it does not clarify. Do banks have limits or not? :-)

The theory sounds pretty clear to me.

Let’s define two different types of limits: technical limits and nontechncial limits. Then, let’s talk a lot about how there are no technical limits on the ability of a bank to keystroke its way to trillions of dollars of loans.

Oh, but let’s also do a little CYA and mention that, yes, technically speaking, a bank may have nontechnical limits. But ignore those nontechnical limits. Because we said so. I mean, in the real world, a bank would never actually go insolvent. No management team would risk such a blot on their reputation.

Then, let’s define new money creation as only involving the technical limits. Yay, now we have a new model based on ability of banks to create money without backing from the government.

Of course, banks may need government support in the bust times, but that’s like totes unrelated to their ability to lend in the boom times.

***

Is that a little harsh? Yes. But the burden is on academics claiming to have a better description to demonstrate why their semantics are actually a notable improvement.

Actually, the concepts of the money multiplier [hence the related concept of “bank money”] and loanable funds both existed simultaneously in my econ 101 book in college. But they were in different chapters.

The money multiplier, a consequence of fractional banking, does have a mathematical limit and it depends on the reserve ratio. Of course since banks are in the middle, they have control over whether they lend to the limit or not, if loan demand is there. If no loan demand, they would be “pushing on string”, which was in yet another chapter in my econ 101 book.

A common layman misinterpretation of the money multiplier is that banks have their own printing press. That is not true – the banking system a whole creates bank money. When a loan is made, the bank now has an “asset” on it’s balance sheet. That where “capital ratios” come into play limiting an individual bank.

Here’s a belated thought. A concern about the system of money creation. Banks extend too much credit which is followed by pushing the investment of that credit into stuff that will never pay off – then comes the corporation that has aggressively tried to make its investments work and has landed a contract to import a bunch of junk back into the US but for some reason or other this corporation does not pass certain standards (because productivity) and the result is a big Tribunal settlement. In favor of the corporation. In a country that continues to “create” money and write derivatives to cover any losses. Isn’t this a bad recipe? When the insurer of last resort is clearly the Fed.

Are you being sarcastic? I am just asking because it is my understanding that many banks were technically insolvent immediately preceding the credit crunch and it was this fear of mutual insolvency that precipitated the credit crunch. The credit crunch led to a financial crisis, which necessitated a public bailout of the insolvent financial institutions.

Don’t doubt yourself; washunate lives in a very different world. The danger she/he presents is a total belief in the infallibility of their opinions coupled with a disregard for the importance of knowledge, something which has noticeably worsened over the last two years. The big banks were hit with both cash-flow and balance sheet insolvency during the GFC and had no way out. “Technical non-technicalicity” aside banks that go wrong can either implode or be rescued.

That’s the same argument we heard from neoclassicals regarding fraud and it appears washunate is once again hoping to drag us back toward the neoliberal consensus

I took it as snark.

Yep, I assumed that was pretty obvious. It is inside baseball of course, but I thought it was pretty mainstream. It’s been so many years I can’t even remember who actually claimed that fraud can’t happen in a market because it would hurt a firm’s reputation and they would go out of business. Greenspan maybe?

Yep, that was sarcasm. I thought Jesper’s original comment about clarity set the tone there, but yeah, it was meant dryly.

Capital ratios, depending on how many SIVs you have. But if you get limited there, those numbers can be fudged. Or if you don’t like faking complicated financial statements, you can always say, “faakit, I don’t wanna be a bank. I’ll be a CDO mill instead. Then maybe expand into insurance with CDS. That sounds better.”

But economists are hopeless. They spend 50 years arguing over whether the sky is blue or green, then one comes along and says it’s blue-green.

But of course, if you are allowed to mark your assets to market and take the profits into capital then in a bull market banks with large tradeable assets will see their capital soar and so capital constraints can disappear – until the bear market of course puts it all into reverse.

I confess I am out of touch with what regulators allow nowadays so this is probably academic (or so I hope).

Mark-to-market is only cool depending on circumstances. In the last crash, regulators waived it because it made banks look like they were broke! If banks are broke they might cause a “credit crunch” and kill the real economy. Oh wait…

They did

My wife is in real estate and couldn’t figure out why banks would not.sell foreclosed properties.

I explained that if they did. They would have to actually take a.loss instead of having the house.as.an asset on.their.books for whatever the bank said it.was.worrh

They got it on the other end too. All the “toxic waste” – the securitized loans like subprime and even higher quality MBS became suspect. If marked-to-market that made them look insolvent because the capital ratio requirements are so lax.

At the same time they get cut off at the “liquidity” end – banks stop lending short term to each other because they perceive risk – the big party is ending to it’s time to head for the bomb shelter.

But that’s when our Fed comes to the rescue and squirts in the 20 trillion or whatever in loans to help the folks weather the downturn and keep bonuses intact.

This is crucial. Jamie Dimon is believed to have recently become a billionaire, and he would never have achieved this status if his bonuses and other compensation had been impaired. God’s Right Hand Man Lloyd Blankfein also wants to become a billionaire, and needs uninterrupted bonuses. If bankers and hedgies don’t get their bonuses, the number of American billionaires will drop, and our society might become slightly more egalitarian.

The consequences for the egos of prominent sociopaths would be tragic.

so true.

No, that was not the reason. We wrote about this at great length during the foreclosure crisis.

Most mortgages, and the overwhelming majority of subprime loans, are securitized. The owners are investors who are passive. They aren’t managing the relationship with the borrower. That is 180 degrees different from the old model, where banks kept the loans on their books.

At the time the deal is done, the management of the mortgages in the trust (4,000 to 5,000 in a typical deal) are made the responsibility of a mortgage servicer. That is usually but not always a unit in a bank. But this unit performs administrative services. It collects money from borrowers and remits it to the investors. It also keeps records.

The servicing contracts were set up to pay the servicers fees to foreclose. They did not set up to pay them to modify mortgages, which is actually a ton of work. Foreclosing is thus both easier and more profitable for them, even though much worse for investors in the overwhelming majority of cases.

The bad outcomes are the result of bad design and bad incentives.

Yes. Big ones. So big that it became necessary to start writing up more derivative contracts than loan contracts. This post explains derivatives better than anything I have read and it doesn’t mention them once! But really, why else would Greenspin love them so much. Because it was the perfect way for banks to have all the cake and eat all the cake. As long as banks’ balance sheets were OK, they were OK, except that they could crash the entire world economy and then, oops, they weren’t OK any more. So enter derivatives to ensure their own balance sheets. Problem solved.

These guys call banks’ “own assessment of the implications of new lending for their profitability and solvency” the key limit to lending. This is a kissing cousin to Greenspan’s assumption that self policing rational agents in management act as universal stabilizers, except that rationality doesn’t show up anywhere here. Instead we have the conscience and moral compass of bankers.

Hello risk deferral — in the form of contracts that read like non-linear calculus. The risks are born by those of us who can’t do the math.

What is the policy value of such academese?

If banks could create new money, they wouldn’t need government bailouts.

This is not academese, it’s the reality. Read the BoE explanation of the same in Money creation in the modern economy.

Banks create money when they issue loans to others: they obviously can’t issue a loan to themselves should they find themselves in a liquidity/solvency crunch. Hence the need for bailouts by somebody else.

How does an entity that can create new money encounter a liquidity/solvency crunch?

This is the problem with using imprecise language like money.

Banks create deposits which are money to non-bank businesses, individuals, state and local governments and sometimes foreign governments. Deposits are however, not money to other banks. Settlement balances (money in essentially bank’s checking accounts at the central bank) are money to them (in the sense that they can use them to settle their liabilities). A bank needs these to clear payments with other banks and the government. Normally the central bank makes sure there are enough settlement balances in the system to clear payments between banks and those balances are distributed through the banking system when banks make daily unsecured loans to each other. In the crisis however, since all these loans were unsecured, banks stopped lending to each other. The government then had to guarantee interbank loans in the trillions to get the payments system functioning again. Bailouts serve to make people believe the financial system is stabilized and to increase their official capital levels (capital levels matter because regulators are supposed to take over and resolve banks that are under-capitalized or even have negative equity). They are however, not essential to keep these banks going. Letting banks lie about the value of their assets (which happened on a widespread level after the financial crisis) is just as effective as keeping these banks running as official bailouts. The dirty little secret is that as long as the central bank makes sure that banks can borrow on the inter-bank loan market (or directly lend to them) and regulators all agree to lie (or not check) about the net worth and capital levels of a bank, they can stay in business. This is the nature of accounting control frauds in the modern age.

So that leaves my original question. What is the policy value of the semantics?

In your description, banks are still constrained in their ability to lend. In order to loan more, to create new money, government has to make sure the bank IOUs are interchangeable with the national currency.

a) this is not true. in payment systems where bank liabilities don’t trade at par (like antebellum united states) what adjusts is the value of the liabilities, not the banks ability to issue liabilities.

b) the definition of a modern currency is making sure that insured deposits in the same country equal each other in value. The most important Central Bank mandate is to preserve the integrity of the payments system. not putting enough settlement balances into the banking system means making interest rates explode and the payments system freeze. If you think that banks are at all constrained in lending by the threat of the central bank deliberately blowing up the payments system country wide, I have some penny stocks i would like you to invest in. What’s interesting about Europe right now is that they don’t have a “federal” (as in europe wide) insured deposit system and thus there is no such thing as insured deposits in the normal sense. as a result the ECB has blown up the payments system in cyprus and seems to be contemplating doing the same in Greece and wrote down deposits (in many ways like the antebellum banking system). Note that even in this case lending hasn’t been constrained, the resulting liabilities have just been written down and may be written down in the future.

C) saying that banks are “constrained in lending” when this “constraint” is something that doesn’t exist in the real world ie the United States and most central banks in the world refusing to provide the necessary amount of settlement balances to clear payments between banks at par is much more of a semantic game with no value for understanding policy than the reverse.

I hear what you are saying. What you are saying is that there is no alternative.

The public must bail out the banksters.

This is purely made up by you and has nothing to do with what I said. Making sure that insured deposits all equal each other in value is not the same as making sure we always protect banksters. Writing down deposits may in certain circumstances hurt wealthy people more than ordinary people, but it does hurt ordinary people immensely. writing down deposits doesn’t punish banksters. The proper solution to banksters is to actually regulate them, foreclose on them when they are under capitalized and throw them in jail when they commit fraud. that’s how you deal with banksters, not attacking depositors.

Attempting to equate making insured depositors whole and making sure payments clear with unlimited support to banksters is an extremely feckless conflation

I can tell this is hitting a nerve and don’t want to get too deep into back and forth (although, apparently quantity of comments is something that influences our overlords in DC, so maybe we should continue…). But I don’t think you’re addressing the issue. What does this view of money change about the policy options?

As far as details:

And if liabilities exceed assets plus retained earnings, then it’s a big oops. That’s a very real constraint. A bank that takes on bad liabilities relative to assets does not remain a viable entity. Or it gets bailed out by the government.

And undercharging on the cost of deposit insurance is one of the ways in which government has to bail out the banksters. The system wouldn’t work if the actual cost of this deposit insurance was applied to banks.

In other words, there is no alternative. The government can’t not back the banksters. That doesn’t mean that banks create money through loans. It means that public policy has designed a system where the lesser of two evils is to accept the bankster funny money as if it were actual national currency money.

Lending is absolutely constrained. These banks would be out of business otherwise.

My original comment was questioning the policy value of the money creation view. I wasn’t making any claims about constraints. But since that’s where conversation naturally led, I would definitely argue constraints make more sense than new money creation as a soundbite explanation. Bank lending is constrained by the ability of the bank to get Other People’s Money. That can come from other banks. It can come from depositors. It can come from equity investors. It can come from laundering international drug flows. It can come from the government.

But the money absolutely has to come from somewhere. It is not created out of thin air. Bank lending converts the credit of the borrower into the unit of measure of the credit of the nation. It’s an exchange. The borrower gives something to the lender, and the lender gives something to the borrower. This process does not create additional net aggregate credit.

Indeed, if banks systematically get less from borrowers than they give them, they will ultimately require government support to maintain operations. This is why so much lending is now directly backed by the government. No bank can give a home loan or a student loan or an auto loan at present prices without a little somethin’ somethin’ kicked in from Uncle Sam.

P.S., thought it might be good to address the accounting equation specifically. When liabilities exceed assets (negative book value, negative shareholder equity, no retained earnings, retained losses, shareholder deficit, etc.) that of course doesn’t immediately make it impossible for a firm to continue operations. So in that sense, I agree, there is no constraint. In a world where everyone would continue doing business as normal with an insolvent bank, an insolvent bank can continue making loans indefinitely. Indeed, there is no limit to the scale of the insolvency beyond the ability of computer systems to process very large numbers.

But that’s not what actually happens. What actually happens is that a company whose assets are notably less than its liabilities finds it increasingly difficult to turn its promises to pay into the inputs needed to continue operations. That’s the constraint. Bad lending, lending that creates a mismatch between liabilities and assets, ultimately ends in either an inability to continue operating, or a direct injection of government support. To say that’s not a constraint is to play with definitions, not describe the fundamental nature of making bank loans.

You didn’t respond to my last post which is directly relevant to most of the premises you repeat in your response.

These are some interesting observations. Regulatory oversight should constrain lending. Providing reserves to back fraudulent lending has sustained us in this crisis which has reverberated to Greece.

This decision to back the creditors at all costs is having a large backlash. I think AEP just did a nice job of laying out some of prospects of this extend and pretend policy when it reaches the limits of what it can extract:

“It is obvious what is happening. The creditors are acting in concert. Instead of stopping to reflect for one moment on the deeper wisdom of their strategy, they are doubling down mechanically, appearing to assume that terror tactics will cow the Greeks at the twelfth hour.”

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/economics/11687229/Greek-debt-crisis-is-the-Iraq-War-of-finance.html

Wow! I think I have a glimmer of understanding now. Thanks.

They can’t create money for the payments system. U.S. banks don’t make dollars. British banks don’t make pounds sterling. They make bank IOUs for the deposit system.

I am not sure this is completely true. The point of secularization is to sell these assets into the shadow markets. So not the markets hold the assets just created by the banks while the bank takes their money in exchange.

To create more money, all they have to do is find more loans to underwrite, then secularize the results.

Banks can create money denominated in the government’s currency but they can’t create that currency. If you get a bank loan for $10,000 you’re being given a bank IOU with a value of $10,000 — which means the bank isn’t actually loaning you anything at all. They’re agreeing to clear a payment through the reserve system in exchange for a series of small payments from you in the future.

Actual dollars can only exist in a reserve account or as cash.

So far no one is mentioning the elephant in the room: why are money and credit necessarily interconnected?

We could certainly have money, produced in a quantity that matched underlying economic activity or population growth or something. On top of that we could have savings, investment, fractional lending etc.

Instead we have a system where every banking crisis is also a monetary crisis.

Milton Friedman suggested a desktop computer that created 2% more money each year.

Then there are those who suggest using some rare, shiny substance that is materially difficult to obtain:

http://www.alt-m.org/2015/06/04/ten-things-every-economist-should-know-about-the-gold-standard-2/

Instead when we get a banking crisis (year 7 and counting) the only possible response is to flood the system with scrip, with predictable results (runaway inflation, this time in financial assets, last time in housing, the time before in commodities). Everybody moaning about the plunge in oil prices, but nobody seems to ask how/why they got to $140/bbl in the first place. Excess capacity everywhere you look, from Chinese steel to US college grads.

So let’s have a real debate, not just argue how many angels are on the head of our current money/credit pin.

HAL, this is an MMT site. You have been around long enough to know the dominant view, that money and credit are the same thing. Rather than being an unacknowleged pachyderm it has been discussed over and again.

Gold won’t work because wages and prices are sticky downward; Greenspan’s computer idea was based on the notion the above post has refuted, not to mention it fails to account for Minsky’s instability hypothesis.

Gee, I don’t know, to me it’s about the real-world outcomes, not the theories, when money and credit are one and the same we get stuck with the same old problem: banks lend too much and go bust, and you have to debase in order to keep the system alive (or, heaven forbid, repudiate). Every CB in the world has drunk Bernanke’s Kool-Aid that price deflation is bad (oh, the horror, increasing productivity means things get cheaper, as Jim Grant points out, that used to be referred to as “progress”). Credit as the sole transmission channel for money to reach the real economy means that lending must expand forever; which of course it can’t, and doesn’t. Banks can print the principal, but they can’t print the interest, so in desperation Ben Yellen and his/her counterparts pump a new transmission channel: financial assets, and we get Bizarro-world where CBs are just highly-leveraged hedge funds that can “never” get a margin call (Kuroda will own 100% of Japanese equity ETFs by 2017). And 85% of stock market gains go to 5% of households.

And wouldn’t it be nice if wages *were* sticky downward. I’d also like to hear what the MMT crowd thinks the way forward is from the debt overhang tsunami we have today, more extend and pretend? Keep things zero-bound so the debt can be serviced? As I said the amount of excess capacity is already gargantuan, debt pulls demand from the future to the present, no wonder nobody sees any demand looking ahead. 7 years on with the economy “doing great” and Ben Yellen is petrified of even a single 25 b.p. rate rise? I thought we learned that wage and price controls were a bad thing? The most important price in the world is the price of money, and having a monetary Politboro adjusting the dials won’t work any better than Brezhnev’s apparatichiks telling farmers how many cows they should raise because shoemakers needed a certain quantity of leather.

Ummm… gezzz it don’t know Hal…

It seems the trouble actually started with corporatist mythology which allowed them to write their own laws, which in turn, was used to tip the playing field vertically.

You might want to checkout the Wave of Default post imo, your money crank myopia is a bit wanting considering the totality of events.

The Fed was never going to be able to clean up all the endemic corruption and excessive private money creation used to validate the mythology. The Government had to engage in a fiscal policy commensurate to the problem, yet this was hamstrung by the same morons that created the whole problem due to its refuting the mythology’s core tenets.

Skippy…. your red flag baiting is par for course…

Gee, I don’t know, to me it’s about the real-world outcomes, not the theories, when money and credit are one and the same we get stuck with the same old problem: banks lend too much and go bust. . .

Unregulated banks don’t lend too much, they lend to people and institutions that can’t service the debts. It’s bad underwriting.

. . .and you have to debase in order to keep the system alive.

You can’t debase a currency not based on a commodity.

Every CB in the world has drunk Bernanke’s Kool-Aid that price deflation is bad (oh, the horror, increasing productivity means things get cheaper, as Jim Grant points out, that used to be referred to as “progress”).

You don’t have a magic wand that controls productivity growth and neither does anyone else. When you develop your special mental powers that control what the private sector invests you let me know.

This is the sort of thing that illuminates just how misunderstood Keynes is. It sounds great on the surface: “things get cheaper”, as though once again free-marketeers have a wand to cast a cheap-stuff spell. But then a Brit noticed that wages and prices resist falling, sometimes for years. Because they do not adjust downward instantaneously as only a few diehard vulgar austrians maintain, inventories go unsold, businesses cease investing and lay off their workers. Rather than deflation we get depression.

Credit as the sole transmission channel for money to reach the real economy means that lending must expand forever; which of course it can’t, and doesn’t.

Sure it can. What matters is the rate of growth in lending and the quality of the loans.

Banks can print the principal, but they can’t print the interest. . .

They do in fact create the interest which they earn from loans. This is called turnover.

. . . so in desperation Ben Yellen and his/her counterparts pump a new transmission channel: financial assets, and we get Bizarro-world where CBs are just highly-leveraged hedge funds. . .

Central banks don’t utilize leverage and your comparison with hedge-funds escapes me. I assume you just don’t like hedge funds and threw the term in for polemical effect.

And 85% of stock market gains go to 5% of households.

Way off topic, now.

And wouldn’t it be nice if wages *were* sticky downward.

They are.

I’d also like to hear what the MMT crowd thinks the way forward is from the debt overhang tsunami we have today. . .

No, I don’t think you want to hear anything about it.

As I said the amount of excess capacity is already gargantuan

As opposed to what?

. . . debt pulls demand from the future to the present, no wonder nobody sees any demand looking ahead.

Debt has its own time travel technology?

7 years on with the economy “doing great” and Ben Yellen is petrified of even a single 25 b.p. rate rise?

Who is Ben Yellen?

I thought we learned that wage and price controls were a bad thing?

If lowering rates is a price control, then raising them is also such. Why is one price control ok and the other not?

The most important price in the world is the price of money. . .

Says who?

. . .and having a monetary Politboro adjusting the dials won’t work any better than Brezhnev’s apparatichiks telling farmers how many cows they should raise because shoemakers needed a certain quantity of leather.

You previously argued for a rise in interest rates. Now you object to it. This sort of incoherence is why it is difficult to take the comments seriously.

Anybody who counterposes “real world” to theory has a theory about the real world they cannot or do not wish to express.

I’ll just reply here, yes I transposed “real world” to a theory I have but I’m not the only ideologue posting here. The theory I have is known as “capitalism”, what’s yours?

OK one by one:

“Unregulated banks don’t lend too much, they lend to people and institutions that can’t service the debts. It’s bad underwriting.”

Sorry, we no longer have “bad bank underwriting”, we have credit extension by banks who are told by the issuer of the scrip that they will issue it in “unlimited” quantities (to use Draghi’s term) to cover any kind of liability they wish to put on their (or someone else’s) books.

“You don’t have a magic wand that controls productivity growth and neither does anyone else. When you develop your special mental powers that control what the private sector invests you let me know.”

Of course I don’t, and nor does Janet Yellen. The price of money should be free to seek a level that reflects investors’ appetite for business risk. Take a quick look at the accuracy of *every* Fed forecast of said activity sometime, a coin flip would outperform by an order of magnitude.

“Central banks don’t utilize leverage and your comparison with hedge-funds escapes me. I assume you just don’t like hedge funds and threw the term in for polemical effect”.

Gee then why is the official name for the QE Program LSAP (Large Scale Asset Purchase)? We are supposed to believe that the risk of a quasi-entity being able to “purchase” assets by issuing reserves is contained because those reserves will be transmitted into “money” by banks? Oh, except that the money issuers have parked $2.5 trillion in excess reserves back at the Fed.

And yes I *would* like to hear what MMT’ers think the way forward is for debt that can never be repaid and can only be serviced by price fixing money at zero. What is the purpose of an interest rate? Let’s just say money is free and always will be.

“Debt has its own time travel technology?”

If I want a big screen TV today but I don’t have the money I can do two things: wait until a future date when I have saved enough money, or borrow the funds and buy it today. The future demand for the TV set is pulled to the present. Mm-k?

“If lowering rates is a price control, then raising them is also such. Why is one price control ok and the other not?”

I didn’t say I thought rates should be raised, I said they should reflect investors’ appetite for business risk, not the views of some tiny group of PhDs that has been serially, categorically, and uniformly wrong.

“Who is Ben Yellen?”

I blended the names of the past and current Fed presidents for (weak) humorous effect. The prior president of the Fed’s name was Ben Bernanke, the current Fed president’s name is Janet Yellen. Get it? Ben Yellen?

No response to CBs buying up equities? What is the purpose of that? They either are entities that hold assets and hedge risk (“hedge funds” as I asserted) or they are not. Which is it?

When someone responds with condescension and selectively ignores the harder answers to my questions I know I’ve hit a nerve. Over to you.

Sorry, we no longer have “bad bank underwriting”, we have credit extension by banks who are told by the issuer of the scrip that they will issue it in “unlimited” quantities (to use Draghi’s term) to cover any kind of liability they wish to put on their (or someone else’s) books.

Category error. You’ve jumped from banks to central banks and confused assets for liabilities.

Of course I don’t, and nor does Janet Yellen. The price of money should be free to seek a level that reflects investors’ appetite for business risk.

Category error. Businesses are almost entirely insensitive to interest rates when making investment decisions. Anyone with half a brain knows this, particularly given the quantity of data we have confirming it.

Take a quick look at the accuracy of *every* Fed forecast of said activity sometime, a coin flip would outperform by an order of magnitude.

Irrelevant to your previous comments.

Gee then why is the official name for the QE Program LSAP (Large Scale Asset Purchase)? We are supposed to believe that the risk of a quasi-entity being able to “purchase” assets by issuing reserves is contained because those reserves will be transmitted into “money” by banks? Oh, except that the money issuers have parked $2.5 trillion in excess reserves back at the Fed.

That isn’t leverage. You’ve gotten confused on the terminology again.

And yes I *would* like to hear what MMT’ers think the way forward is for debt that can never be repaid and can only be serviced by price fixing money at zero.

No, you wouldn’t.

What is the purpose of an interest rate?

You don’t know?

Let’s just say money is free and always will be.

Ok.

If I want a big screen TV today but I don’t have the money I can do two things: wait until a future date when I have saved enough money, or borrow the funds and buy it today. The future demand for the TV set is pulled to the present.

If you want it now it isn’t future demand.

I didn’t say I thought rates should be raised, I said they should reflect investors’ appetite for business risk. . .

No you didn’t.

I blended the names of the past and current Fed presidents for (weak) humorous effect. The prior president of the Fed’s name was Ben Bernanke, the current Fed president’s name is Janet Yellen. Get it?

You got confused and are now attempting to cover for it. I get it.

No response to CBs buying up equities? What is the purpose of that?

Prevention of cascade failure.

They either are entities that hold assets and hedge risk (“hedge funds” as I asserted) or they are not.

All financial institutions are not hedge funds.

Just wow.

1. “Businesses are almost entirely insensitive to interest rates when making investment decisions. Anyone with half a brain knows this”.

I guess this says the Fed does not have half a brain. Or? They worry so much about the discount rate…um because why, again? And businesses do not calculate their cost of capital when investing?

2. The accuracy of Fed forecasts are “irrelevant? See #1 above then. Or else great news, they can now fire 90% of their staff.

3. MMT answer for debt which can never be paid and can only be serviced when money is free. *Yes* I would like to hear the answer. Perhaps it’s contained in your later response, “yes money should be free”.

4. What is the purpose of an interest rate? You say I “don’t know?” If the interest rate is intended to reflect the relative risk of business investment, then yes, I do know. If however as you argue that money should be free, that the Fed does not care about rates because businesses don’t care about them either, then you’re right: I do not know the purpose of interest rates. Free money for all. Have you ever considered running for political office? That would be a killer slogan.

5. Future demand: semantic tricks. Free money says that future demand is equal to present demand that is satisfied, all it requires is more debt. So I should borrow today to buy everything I want in the future, no problem, I can just get unlimited free money now and forever to do so and I have zero cost to service that debt.

6. CB equities, “prevention of cascade failure”. Um what? I thought you said CBs had a magic supply of free money forever? How can there be a “cascade failure” in a system like that? All that’s required, now and forever, is to just add more free money to the system. How can it fail?

Skip the ad hominems this time around please.

Yeah, we very much agree here. Banks can create bank IOUs. Just like I can create wash IOUs. I, wash, do solemnly and seriously promise to give you a trillion dollars next week.

Now, gimme a trillion dollars today!

If the government backs my $1 trillion promise, then the government created the money, not me. If the government doesn’t back my promise, then it ain’t worth jack squat in payments systems. I couldn’t even buy a coffee at Starbucks with it, nevermind a car or a house or something.

How does a dude driving a car with a gas gauge run out of gas?

hahahahah

If you fkk things up so bad you can’t pay for your money making machine to make money then you can’t make money. But it’s not cause you can’t make money, it’s because you can’t pay for your money making machine to crank it out1

How do all these boneheads get so rich if they can’t make money? They could never get that rich if they just loaned money that was already there. No way. They don’t get rich linearly. They get rich exponentially. that’s inconsistent with Not making money whenever they want. Loanable funds is linear. Making is exponential.

Where does the money come from if they dont make money? The first bank had to have money to start. where did that come from? It might have come from the govermint. But the govermint had to borrow it from people. They probably got it from a bank someplace that cooked it up. There was probably a bank in the Garden of Eden. That’s probably what the snake was. A Banker. hahahahahahah. The apple was a loan. Then reality set it when Adam and Eve realized they had to hit the mall to buy some clothes so they could look for jawbs to pay it off.

You read that in David Graeber’s book, didn’t you?

only the part about Satan being a banker. everything else I made up.

God, I love you guys!

Money is not a commodity and as such is not bound by the Newtonian atomistic reality, its only a contract which represents a contractual transaction.

Skippy…. Money is actually worthless without the transaction, that is what Graeber was banging on about…

PS. crazzyman… son just smashed school shot put record by 2.1 meters and its early in the season… whoot!

When banks create money they expand both the asset and the liability side of their balance sheets. Besides issuing loans, they can buy various “reserves” etc on wholesale or intrabank markets, etc.

Each side of a balance sheet is then composed of items of different type of “goodness” (e.g. on the liquidity scale): cash in the vault is pretty liquid, central bank reserves even more so, but , say, retail loans are assets that are obviously not as “good/liquid”.

Various legal definitions of “solvency” are based around ratios of some definition of “debt” to some definition of “equity” or “capital”. These buckets are allowed to contain assets/liabilities of some types but not others. So, as banks expand/shrink their balance books these ratios fluctuate. The definitions are such that it’s impossible for a bank to issue a loan to themselves and suddenly become legally solvent where they would not have been otherwise.

It’s really just arithmetic, but, importantly, a bank may be legally prevented from doing certain types of business once they’be become “legally” insolvent. So they hustle and try to stay above the legal limits (as cheaply as they can do it, of course).

Not exactly, because there’s a roundabout way for banks to escape this constraint.

This is how Richard Werner describes it in a recent (2008) case that involved Barclays Bank:

See Richard Werner: How do banks create money, and why can other firms not do the same?, page 76

They can create money as long as there is someone to loan it to. Bec. they have to mind their own assets and liabilities to be legit. But the trick is that they don’t have to pay attention to reality as long as their books balance. It is such a clever fiction. Theoretically it could work to smooth the bumps in an economy, except that it causes such precipitous crashes nobody can recover. One small detail.

How can an entity that can create money ever have unbalanced books?

When the economy starts to shrink, earning potential goes down as do asset prices.

This prevents banks from making new loans. Banks loans are a function of past and future earnings.

At the same time the ability of the debtor to repay loans on the books is also curtailed.

This.leads.to a bailout.

@washunate:

Now you’re being obtuse. Deliberately?

It’s clear they can create asset-money by loaning asset-money to borrowers.

We’re not talking about paper bills here, which are a very small part of circulating “money.”

No, this is very important. A currency issuer can issue unlimited amounts of currency.

An entity that is not a currency issuer cannot. They are constrained by the existing resources.

@washunate:

Precisely.

But you persist in confusing currency, i.e bills and coins for “money.” Currency is but a small part of total money supply.

The federal reserve reports in 2008 that total money supply “M2” is 7.1 trillion, and the currency portion of that is about 700 billion. One-tenth.

Nine of ten “dollars” are not currency at all.

Did you think the masters of the universe were dragging around suitcases or shipping containers full of hundred dollar bills for their mergers and acquisitions?

Is this clear?

I completely agree the vast majority of national currency units are electronic. Cash has been a rather small portion of overall payments for decades.

And what makes an electronic bank IOU as good as the national currency? The government.

Banks do not create asset-money in lending. Banks take the asset-money of the borrower (such as future earnings or real property collateral), and in exchange, give borrowers currency-money.

An entity that can create money can suffer losses through the defaults of its borrowers.

Of course banks don’t _need_ bailouts. They get them because they are able to coerce the populace through the great circle jerk of the Loanable Funds model!

What do you mean banks don’t need bailouts?

Bailouts are used to bolster the publics’ perception of the Feds’ regulatory authority and responsibility and spread some more wealth around. Look at what happened to AIG!

Exactly, look at what happened. Goldman Sachs would have ceased to exist without government support. The smartest bank on the planet was incapable of creating money.

“ceased to exist” I find that very hard to believe. They might have had to cut bonuses…maybe.

Well sure, we can’t prove something that didn’t happen. But we can point to how desperate actors behaved at the time. For example:

Unusual, exigent, emergency, and expeditious. In just one sentence.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/press/orders/orders20080922a1.pdf

Desperate?! They were handed an opportunity to gorge at the Fed discount window by becoming a bank holding company!!! They didn’t hesitate and the rest is history.

Your comprehension seems to be so much neoliberal twaddle…meant for the proles. Of course they had their avarice covered by so much high-sounding legalese.

It occurs to me that this whole dialogue regarding what banks do is made incomprehensible by the fact that there is a huge difference between a BANK and an INVESTMENT BANK…and for banksters that is as it should be. Bailouts were necessary in the eyes of the PTB solely because with the repeal of Glass Steagall, the new entities were allowed to create incomprehensibly complex legal relationships that tied the new entities’ various businesses together across global networks, thus creating for certainty that our payments system would be vulnerable to a major failure of potentially any significant portion of the new Investment Bank Entity. In the case of Goldman Sachs, while they did not have any part of their Investment Bank Entity active in the payments system, the balance of their business was so intertwined with other entities who did, that a chain reaction would occur which would have the same effect. Thus GS was allowed to become a “bank” in order to save the payments system. Banks that are too big to fail are truly too big to manage and, more importantly, too big to administer under our present laws, without jeopardizing our payments system. This is the elephant in the room! Please, someone tell me how an investment bank failure, by itself, can jeopardize our economy? No matter the size of the entity, as long as it cannot jeopardize the orderly payment of our bills, our laws have always been able to manage allocation of the losses and life moves on. Understand this one point, TPB say that managing capital is the key. If that is so, how come such absurdly small amounts of “capital” can jeopardize our entire economy? I’m a retired CPA and I can tell you that this remedy of properly managing capital is nothing but pure BS. Talk about what is $.02 and $.02 being whatever you want it to be, that’s funny. But we are talking about how about you make $100M become $100T! and that’s not funny. SIVs, Tier 1 through whatever, Mark to Market (when it helps, otherwise never mind). We are truly insane. If you want to understand what a bank is or is not and what it can and cannot do, you first have to have an agreement on what a bank is…and it is surely not what we have today. My parents’ generation possessed the wisdom to pass laws that precluded what we have now, and we just plain blew it when we elected Slick Willie. The answer is simple and right in front of our face, but we argue about anything but. Baby Boomers were at times smarter than their parents. In the case of Glass-Steagall, we were dead wrong.

Also, If banks could create new money, they wouldn’t need to borrow depositors’ money.

And, If banks could create new money, you wouldn’t need depositors’ insurance.

All of these speak to the “banks create money” idea as nonsense. Banks create credit.

However, the “loanable funds” idea is still nonsense. Loans are both made from and deposited to loanable funds, for a net of zero. This is critical, because it completely nullifies the idea that government borrowing affects interest rates by creating a shortage of funds. Government spending does not slow other financial activity in the economy, which means the entire conservative paradigm in macroeconomics is garbage.

Well said, it’s all nonsense.

Personally I would tweak “banks create credit” to more specifically say that banks convert borrower credit into government credit. It’s a transformation, an exchange, not an act of creation. It’s the borrower, not the bank, that supplies the credit. Indeed, a bank that systematically makes loans exceeding their borrower’s ability to repay quite predictably goes out of business.

Yes, the borrower creates the money when he signs the loan documents. Banks do not create money, just convert this borrower money to government money. Loans create deposits.

As Sardonic and Susan the Other have both pointed out, banks create money only when they issue loans to others. They aren’t able to create money in any other ways. If there aren’t borrowers, then the banks can’t create money. And when someone fully repays her or his bank loan, the money that was created by that bank loan is destroyed.

But of course the bankers have a multitude of ways to game the system.

“And when someone fully repays her or his bank loan, the money that was created by that bank loan is destroyed”

But then at that exact moment, the bank has gained an equal capacity to make a new loan.

And the borrower now owns a house asset.

Bankers have far worse ways to destroy money.

Huh? Have you not gotten a credit card offer in the mail? They offer to run up your credit line and deposit the money in your own bank account. You can borrow and get the proceeds of the borrowing yourself. Similarly, companies sell bonds and the proceeds of the sale of the bonds go to the company.

Credit card loans are bank loans. People’s Visa and Mastercard accounts are always underwritten by a bank such as Bank of America or J.P. Morgan Chase. The credit card loans are loans from a bank to a person, which is exactly the type of money creating loan that I was discussing.

> Also, If banks could create new money, they wouldn’t need to borrow depositors’ money.

They don’t NEED to, and in fact many banks (e.g. the old Investment Banks) do not do so (or didn’t, until they had to in order to be eligible for bailouts. Here’s looking at you, Goldman).

I think banks today just take depositors’ money because it’s another profit stream, it bolsters the capital ratios, and because once you have a relationship you’re more likely to want one of their loans too. BTW, the banks immediately think of your deposited funds as theirs, so using the phrase “borrow depositors’ money” is a recipe for a future misunderstanding between you and your bank.

> And, If banks could create new money, you wouldn’t need depositors’ insurance.

You need depositors’ insurance when (a) you don’t trust the bank to give you back your deposits when they do not want to, but you trust the government to do so. Or alternatively when (b) people who have been loaned funds by one bank decide, on net, to deposit the proceeds of those loans into others bank, and the government decides not to fill the gap, thus forcing the original bank into insolvency. The bank will remain insolvent no matter how much new money it can “create” as deposit/loan pairs. (Here’s looking at you, Lehman and Greece…)

> All of these speak to the “banks create money” idea as nonsense. Banks create credit.

Of course banks create credit. We just call it money because money as we knew it is dead, no one has admitted it yet, and credit is the closest thing we have to what used to be money. The dollar as money, in the classic “store of value” sense, died when Nixon killed the gold standard.

I’m starting to think that this fractional reserve banking idea was a wrong turn in human history.

It put idle capital to work. There is nothing wrong with that.

When you go and try to squeeze money out of every asset on earth is when it causes problems.

Were not using fractional reserve banking, hence you can’t even make a wrong turn with something that does not exist, in the first place.

It’s easy to make money when you can lend the same $100 to ten different people.

Money is credit, so your statement does not make sense. What is happening in the scenario you imagine is you are creating ten different loans. These dollars are no more “same” than are numbers in different banks demand deposit accounts.

Since we run massive trade deficits there are.always dollars.offshore that can be lent to banks to meet any reserve requirements.

So banks ability to make.loans and create money would be a function of society’s ability to repay.

Another point, banks don’t create money out of thin air, they create money based on prior earnings (secured loans) or future earnings (unsecured loans).

Bank loans aren’t derived from cash flow, they are entries on the balance sheet. They come from nowhere and go back to nowhere when a loan is paid back.

Also, all dollar deposits exist within the computers of the Federal Reserve so there’s nothing “offshore” to bring back.

Not all dollar reserves are sitting in the federal reserve , although many are.

And cash flow of the borrower matters.

All dollar deposits exist on computers at the Federal Reserve. Anyone at the Fed, Treasury and CBO can tell you this.

Cash flow of the borrower is a matter of underwriting standards, not capacity to extend a loan.

China doesn’t keep their dollars at the federal reserve.

And if your loan doesn’t meet the underwriters standard for cash flow, you don’t get a loan. Seems like a constraint to me.

Are we arguing semantics here?

All non-cash dollars are sitting on bank-accounts all around the world. These accounts sits on their respective centralbank-account. And every dollar centralbank-account sits on the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

I guess all interest-bearing dollars as US government bonds also “clears” through FED NY. I think that there are no more “bearer certificate” available in US Treasury-paper.

Are all ‘banks’ the same?

In a regime where the banking authority imposes a strict 50% reserves requirements and eliminates the gimmickry of overnight sweeps to gimmick the base of assets and liabilities, and stresses certain types of higher quality reserves and a conservative valuation, are the ‘banks’ the same as a regime where reserve requirements are minimal and easily financialized?

Is an economy where loans are intimately tied to organic growth through ‘real’ economic activity and a high velocity of money (sorry Austrians but it does mean something) different from one in which the banks are largely preoccupied with speculating with their own trading books and money supplied by the central banking authority monetizing debt?

A model that fits a particular circumstance which is itself is rather distorted from the historical norm is just that. An example of a particular circumstance and not a general model for a range of conditions.

Exactly. And I think this is also the flaw in the MMT model: the idea that because this is the way monetary operations work right now, this is a permanent feature of the system henceforward.

This post was killer. It left us all with the question, Well just how do we change our financial behavior to fit the real model, the money creation model. Because we all went blithely on our way for decades thinking things were balancing out when in fact they weren’t. It sounds a little Minsky, in that the good times always crash but nobody knows what to do about it. So at least Minsky had an inkling of this. And there were plenty of crashes when banks really did intermediate loans, but they were recoverable. When did loan intermediation end? 1913 and with the creation of the Federal Reserve? If so it is amazing it was mythologized for so long. One way to begin to get real would be to analyze the value of money, and its creation, by what it accomplishes. So, that’s after the fact and hard to do in a “free market” but the FM is also another myth. MMT looks at this very clearly. We don’t need loans to run the sovereign business of the country. That takes care of a large chunk of the mess right off the top.

Except that in the alternate MMT Universe – the one where the printing press has been re-located from the Federal Reserve to the Treasury – Jamie Dimon is President of the United States and has 10 times as much money as Putin in a numbered Swiss bank account.

yes. it’s scary. Mistakes are easier to make than progress. But we have much better analytics now… maybe we can estimate what will happen and actually maintain a steady course. I’d like to think that.

Step 1. When did loan intermediation end? 1913 and with the creation of the Federal Reserve?

Step 2. Getting off the gold standard in 1972.

I believe.

Back in the free banking era of the 19th century, there was a bank in Rhode Island that issued $600,000 in bank notes backed by 7 bits ($0.875 in coins) in the vault. ;)

Source: A talk on CSPAN book TV a few years ago. Sorry I can’t be more definite.

That was back when we/Europe were still trying to decide if we should do fractional gold banking, or if banking based on the banker’s reputation was adequate. ‘Course bankers found that cheating on fractional gold banking was very profitable as well.

The basis of loans create deposits has been around since shortly after the creation of double-entry bookkeeping. The FED’s existence only stabilizes and standardizes the interbank clearing process and has little to do with loans create deposits. The gold standard only fixed foreign exchange rates and floated domestic rates, it had little impact on loans create deposits.

According to Lombard Street (1873) by Walter Bagehot lending as a function of ‘banks’ preceded their accepting of deposits by some years.

Can’t we all agree that banks create money? Fractional reserve banking makes no sense unless banks create money. I learned that in high school, fer crissakes!

No, we can’t.

:)

But seriously, it’s important to understand why there are differences of opinion. The monetarists (of all stripes, this is not a left/right thing) want people to think that money (as in currency) is created by banks because that obfuscates the real actor – the government.

When the government accepts the bank IOU as exchangeable 1:1 with the national currency, then it is the government that has created more currency units, not the bank. But if people can be convinced to ignore that little step, it looks like banks create the currency units themselves.

And once you accept those bank IOUs as legitimate currency units in the boom times, well, you’ve committed to a policy of bailing out criminal and/or insolvent management teams during the bust times.

Banks don’t create money. You were taught wrong. The model used where banks create money does not match the accounting a bank uses. There is no money multiplier.

[Note that several first world countries have reserve requirements of zero percent. They do not suffer hyperinflation, as the money multiplier would suggest. Even Ben Bernanke said that the reserve percentage only affected the cost of money, and that he would have preferred the US also move to a zero percent reserve.]

Banks create credit, but common usage sometimes interchanges money and credit when the distinction isn’t relevant to the narrow context of the discussion.

There is a money multiplier. No one made it up – if you have fractional banking it is there. Math says it can happen. You could call it a credit multiplier if you prefer, but I try and limit how many new words I make up.

The reserve ratio limits the money multiplier to a non-infinite number. The reason we have bank reserves is so in theory banks have some cash on hand to satisfy deposit withdrawals.

Capital ratios are used by regulators to monitor bank solvency. Some counties have zero reserve requirements. I guess the CBs there will FedEx your money to you. Who knows. I’ll take the FDIC insurance.

Canada has a 0 reserve requirement. Canada has a housing bubble. So does Oz. The EU has even more lax capital ratio requirements than the US. The EU is now a basket case. The US has asset bubbles.

Bernanke is an a-hole.

when Y is talking about investment / saving, she is talking about the real side of the picture.

when you are talking about the loan-> deposit causality, this is from the technicality of the financial system.

both are correct because they are talking about apples and oranges.

the money multiplier story is something that economists have spread and they are _so_ surprised to find out that it is not the (complete) truth. partly this story comes from history because that is how banks started. That is because gold is a real resource – you cannot just create it fictionally and lend it. Now that money is nothing, there cannot be a shortage of nothing, unless it is to keep the “people in their place”. When the likes of Goldman have a shortage of money, it is produced out of nothing.

The view of money multiplier is correct, except for the causality part. loans create deposits, but those deposits belong to someone.

From the operational side of things, there is not much difference. Whether the bank creates loans and then deposits, or deposits first and then loans, the fact remains that the bank is on the hook for the loan (to its capital reserves) if it defaults, so the bank has to be careful whom to lend to. Reckless lending can even lead to jail time for the lender (or it used to).

so long store short, there is not much to see in this technical view of things. Yes under the hood the car is very complicated, has 80+ microprocessors and so on. The function of the car is to be driven. To obsess about spark plugs is to forget the function of the car – transport.

This is the real question – what is the function of money in the real economy, who is benefiting from the legalized frauds, and how to stop this and bring finance to serve the real economy, not vice versa. This is political economy, not really finance. Yes to fix something you have to understand it. But it should be understood that we diagnose in order to prescribe.

Couldn’t agree more. More energy needs to be expended prescribing alternatives to the current exploitive system. The root of this exploitation stems form the capture of Government power by interests not serving the public good. It’s hard for this idea of Government capture to sink in for ordinary Americans. What does it mean when corporate interests out-way the needs of the people? What happens to a society when the citizens no longer look to their Government as a power structure designed to improve their daily lives? What happens to a society when it’s military and police forces no longer protect the citizens but exploit them?

This is political economy indeed.

Wow – A few days ago Maxine Waters wrote an op-ed about the 2-tier justice system when it comes to bankers – surprisingly printed by American Banker. So I try to click on it and the link is DEAD. So I search for the article and found it cross posted on 3 other sites – and on each one the link was broken. WOW. And we wonder how the “2-tier justice system” became that way…

See dead links below:

Big Banks and America’s Broken, Two- Tiered …

http://www.americanbanker.com/bankthink/big-banks-and-americas...

Jun 16, 2015 · In February, federal prosecutors began a 90-day examination to determine whether to bring cases against individuals for their role in the 2008 financial …

Big Banks and America’s Broken, Two- Tiered …

grabpage.info/t/www.americanbanker.c…/bankthink/big…Cached

America, American, Bank, Banker, Banks, Big, Bond, Broken, Buyer, Justice, Mortgage, National, News, PaymentsSource, System, The, Think, Tiered, Two, and

Big Banks and America’s Broken, Two- Tiered …

housingindustryforum.com/industry-newswire/american…Cached

Jun 16, 2015 · … Two-Tiered Justice System By American Banker | June 17, 2015. SHARE Read Article. Comments.

It seems to have been moved here. For now, at least…

that’s it!

from now on, if you need money, come see me. i am officially a bank.

Yo necessito algunes million dollares para conducir algunes operationes

militpolitical (askar PanchoV para detailes). Por favor versar el dinero al Banco Nacional de Juarez, 1666 Avenida de la Revolucion, QPX310, Ciudad Juarez, Chihuahua. Muchas Gracias.Adding epicycles to dynamic stochastic general equilibrium models, because markets (I would argue) do not equilibriate (though they may be equilibriated, as with LIBOR).

Trying to make a “like a fish needs an epicycle” joke here, but gotta run….

“Figure 2 shows impulse responses for a shock whereby, in a single quarter, the standard deviation of borrower riskiness increases by 25%.”

So it looks like in this model “shocks” just come from outer space. There is no sense in which the system itself generates crisis as part of its very working ? And where’s the fraud parameter ?

Some central bankers believe that banks create money.

Some central bankers believe that financial markets can self-regulate.

Given the above facts about central bankers, can we conclude if central bankers always know what they are talking about (even when it comes to monetary policy)?

ok, so I understand that loans create deposits, but…im confused about the reverse.

I have this crazy exercise i try to do.

I try to visualize the thought experiment of all loans and govt deficits being paid back so that there are 0 us dollars in existence. (kind of like an economic version of reimagining the big bang in reverse)

Leaving aside for the moment the fact that there is not enough money in existence to make all interest payments… (is this even true?)

how does the money get destroyed when a loan is paid back? You will say “the balance sheets are simply adjusted, a deposit and a loan simply disappear.”

i can visualize this, but i dont understand it.

So what is the difference, for the bank, between a paid back loan and a default on the loan?

and what happens to the interest payments (when they are made)? they move from deposits to reserves (or equity or whatever)… how are they seperated from the deposits that simply “disappear?”

I would really like to understand this…

“So what is the difference, for the bank, between a paid back loan and a default on the loan?”

when a person makes a principal payment on a loan their account is debited and the value of their debt (an asset to the bank) is decreased. when a person defaults on a loan the value of their debt ( again an asset to the bank) becomes zero (well actually more like pennies on the dollar since it will likely get sold to a debt collector). In other words, one shrinks the bank’s balance sheet while keeping it’s net worth the same while the other decreases the bank’s net worth

“and what happens to the interest payments (when they are made)? they move from deposits to reserves (or equity or whatever)… how are they seperated from the deposits that simply “disappear?””

interest is paid in the same process ie debiting the borrower’s account. the difference is that interest payments increase the bank’s net worth since they have less liabilities ( ie less deposits) without decreasing the value of their asset (the borrower’s debt).

In short, banks lend to increase their net worth.

do you mean “the banking system’s net worth?”

if (in both cases) the loan asset value goes down, the only way net worth stays the same is if deposits decrease proportionately.

What if your deposit account is at another bank? What is the difference, to an individual bank, if its a default or principal payment?

Their liability side doesnt change…

Clearly i am missing something…

I do not mean banking system’s net worth.

“What if your deposit account is at another bank? What is the difference, to an individual bank, if its a default or principal payment?”