Greece’s creditors are not pleased, and perhaps more important, the Greek government has lost one of its few remaining advocates, Jean-Claude Juncker of the European Commission. The Eurocrats are finally waking up to the degree to which the two sides have talking past each other. The implication is that it is far less likely than they had believed.

The state of play. Greece submitted two plans in response to the creditor proposal last week. One a short supplement to its 47 page proposal it sent last Monday. The new paper gave some ground on primary surplus targets (where as we noted the two sides were not far apart) and the amount to be raised from VAT (where Greece closed a bit less than half the gap). However, Greece’s plans are still deemed to fall well short, in terms of detail, in terms of how the government will meet the primary surplus targets From the Wall Street Journal:

European officials quickly dismissed a Greek compromise proposal meant to help end a standoff over the country’s bailout program, saying on Tuesday that the offer didn’t go far enough in meeting creditors’ demands…

Greece’s proposal includes targets for its primary surplus—the excess of revenues over expenditures before interest payments are made—that are lower than the targets presented to Greece last week in a new proposal from the commission, the European Central Bank and the IMF, the three institutions representing Greece’s creditors.

“That’s nonnegotiable,” an EU official said. “What’s been submitted [by Greece] is not a basis for further political discussion.”…

“From a technical point of view, it is still hard” to reach a deal, one European official said, pointing out that the counterproposal from Athens still lacked detail on other key areas where negotiators from the two sides don’t see eye-to-eye, such as overhauls to Greece’s labor market.

While this is not a formal rejection, media reports with independent sourcing all had the creditors pouring cold water on the Greek counter. The Greek government also submitted a short document on debt reduction, even though the lenders have said repeatedly that that is not part of the bailout negotiations.

More important, the creditors suspect that Greece believes it can get them to relent an do a last minute deal on debt relief only. We’ve remarked in the comments section, with a bit of horror and disbelief, that both Varoufakis and Tsipras have said that Greece has until June 30 to get a deal done. That’s not accurate.

Any deal, even an extension of the current bailout, would require Parliamentary approvals in some countries, most importantly Germany. And the creditors expect legislation to be passed in Greece too. That mean June 14 is when timing starts getting very uncomfortable (any date after than would require the Bundestag to have an emergency session, which is not going to predispose German MPs towards Greece) and June 18 appears to be the event horizon. Moreover, even if a pact were agreed as of the 14th, the approval window is so short as to be subject to tail event risk, like unhappy minority members of legislatures using procedural tricks to throw sand in the gears and delay approval long enough so that the bailout expires before any funds release is approved. That might mean a new round of bills would have to drafted and passed, creating more chaos and potential for mishap and mischief.

Moreover, the creditors perceive that Greece has vastly overestimated its bargaining leverage. This is troublingly similar to Lehman. Dick Fuld was convinced he’d get a bailout because Bear had been rescued in March (let us not forget that Bear lost its independence, when Fuld was seeking to keep Lehman going in more or less its current form). But the backlash against the Bear rescue was huge, and the Bush Administration made clear it was not about to save another firm. Hank Paulson also conveyed the same message privately to Fuld during their frequent calls (if it were anyone other than Paulson, I’d wonder if I could trust his account, but Paulson has a history of being very direct).

Here, the Greek side appears to believe they will get a rescue as the government did in 2012. But as circumstances changed post the Bear bailout, so to have they since 2012. The ECB has implemented tons of new facilities. Mr. Market seems to have a large degree of confidence in them, since financial contagion has been limited (we pointed out that the volte fact on the IMF payment last week and Tsipras’ defiant speech would be tests of investor worries. Even though stock market fell and periphery bond yields did widen, the reaction was tame compared to 2012.

Keep Talking Greece summarized the key points of a radio interview of Eurogroup chief Jeroen Dijsselbloem:

“I’ve heard a lot of optimism from the Greek side, and it’s an underestimation of the complexity of what’s being asked of them… We’re not even in agreement about what still has to happen before the end of this month.”

The back-and-forth was the latest document exchange between Athens and Brussels as Greece tries to break a months-long impasse and gain access to desperately needed bailout cash. The process has become numbingly familiar in recent weeks — so much so that the European Commission has even given it a name: “paperology”.

But the most recent exchange differed in one vital respect: the mood of cautious optimism that has surrounded the talks in recent weeks is rapidly giving way to fear and suspicion….

Instead, officials from various institutions involved in the talks now worry that Greece’s hard-left government is dangerously miscalculating. Athens, they believe, is intentionally prolonging the negotiations to the last minute in a belief that its creditors will eventually “blink” and agree to grant wholesale debt relief and new bailout cash with few strings attached.

“They do not want a deal with us; they just want debt relief,” a senior official with one of Athens’ bailout monitors said after reviewing Greece’s latest offer.

“I don’t think they will move. I think they’re waiting for us to blink, and we won’t,” the official added. “They don’t understand we’re not back in 2012 where the Europeans were willing to just throw money at the problem.”

So if Greece thinks it has more runway than it has, and also thinks it has more bargaining power than it does, this means much higher odds of an impasse. Mind you, we’ve been saying that there was no overlap between the two side’s bargaining positions for months. The officialdom is beginning to see that.

As a result, Bloomberg is pegging a default as the most likely outcome. The news site moved its estimate to the “more likely” side as of the IMF payment deferral, and pushed it further in that direction today. Note it does not appear that Mr. Market is putting default odds anywhere near this high:

Greece has lost the European Commission. The EC has been the friendliest party to Greece since the February Eurogroup negotiations. From the Financial Times:

The darkening mood was evident at the European Commission, which has long been viewed as Athens’ best ally in the stand-off. According to officials briefed on Tuesday’s meeting of 29 commissioners in Strasbourg, Jean-Claude Juncker lit into the Greek government, saying Athens had “lost the European Commission”.

“They failed to see the best friend of the small and medium-sized member states is the European Commission,” said one official, recounting the EU president’s remarks to his fellow commissioners.

Juncker said he would not attend a meeting set for this evening among Tsipras, Merkel and Hollande on the sidelines of a summit unless he saw a change in the Greek position. He and Djisselbloem suggested the session be cancelled. The European Commission just confirmed that Juncker is not meeting Tsipras tonight and it is not clear whether Hollande and Merkel will confer with Tsipras today or not.

The Greek ruling coalition may be miscalculating in other ways, specifically their exposure to hardliners. One can argue that independent of being boxed in by the Left Coalition, Tsipras’ own incentives favor not giving into the creditors. If he wins what he can present as meaningful concessions from the Troika, he looks like a hero. If Greece defaults but he can persuade voters that the default was the creditors’ fault, in theory he fares pretty well by having put up a valiant fight.

But that ignores what happens after Greece defaults. Assuming that financial contagion is limited, the situation becomes chaotic politically, as the creditors suddenly face a host of decisions as to what to do next (and if the markets react badly, as you’ll infer from the reasoning that follows, Greece is no better and probably worse off in terms of the power dynamics).

There is a group of hardliners among the Eurozone members that are hostile to Greece, and are taking a tougher line than Germany. For purpose of convenience, we’ll call them “ultras”. They include Spain, Latvia, Finland, Austria and Slovakia. They want to make sure that Greece suffers visibly for its defiance since their countries swallowed the bitter austerity medicine. There are separately quite a few ultras on the ECB board, but they won’t act unless they have political cover.

In a chaotic situation, people tend to gravitate around parties that come up with plans of action quickly and advocate them forcefully. That gives the ultras the potential to have influence out of proportion to their political weight. They can also sell radical action as necessary to protect the Eurozone from the existential threat of other countries of the Eurozone also departing, that it is necessary to make a Greek default as punitive as possible pour decourager les autres. That argument could carry weight with other countries and institutions which might not otherwise be punitive towards Greece.

The objective of the ultras would be to break the Greek government as quickly as possible by keeping it in the sweatbox, as in making it hard for the government to access the financial markets, making it clear a Grexit would be worse (for instance, Greece would lose EC agricultural subsidies, and seeing if other de facto sanctions would be imposed). They could also work to undermine the economy by, for instance, publicizing the risk of being in Greece if capital controls or a bank holiday were imposed (scaring off tourists would hurt tax revenues and deepen the downturn). Exporters to Greece are no doubt already nervous and would almost certainly as a matter of precaution insist on fast payment for any shipments before sending new goods. That creates further strains in the Greek economy.

The hope of the ultras and their allies of convenience would be to break the ruling coalition. Their theory would be that a few months of having Greek pensioners and government employees being paid in scrip rather than cash and having other sectors of the suffer would damage Syriza’s popularity and credibility and lead citizens to vote in a more compliant regime.

Now events may not go down this path. But it does not appear that Syriza has adequately allowed for downside scenarios, not merely default, but of what a backlash from European officials might be. It would be better if I were wrong, but this could become even uglier than anyone imagines.

I have no reason to doubt Yves’ analysis above, since her reasoning has proven prescient these past months. The essence of it seems to be that the parties are miscalculating the likelihood of a hard position leading to failure and default. Yves lays out the consequences for Greece of such miscalculation followed by default and further punishment from the European elites.

However, it seems to me that there must also be some contagion effects of a Greek default which the Euro-elites are downplaying or ignoring, just as the U.S. government downplayed/was blind-sided by its decision to allow Lehman to fail.

Capital flight from the periphery to the core seems to me to be the most likely fallout of a Greek default, especially if it is followed by the type of punishment Yves describes above. If such capital flight is not met with ECB support, it could become very ugly.

And, given the ECB’s blatantly political stance in the Greek/Troika negotiations, thereby abandoning its role as lender of last resort, if it keeps that stance up, then such capital flight will only get worse in Spain and Italy if, as and when the likelihood of a (real) leftist government grows in those countries.

As I understand the deposit insurance system in the Eurozone, each country is still responsible for its own banks’ deposit insurance. So, if the ECB stands by as depositors run on Spanish, Portuguese and possibly Italian banks, the threat of “bail-in” of depositors grows greater, which will cause the run to worsen, with growing bank failures the nightmare scenario, just as it was in the U.S. in 1932-33.

That, at any rate, is a possible scenario of negative knock-on effects of a Greek default followed by the type of punishment that Yves describes.

I agree that the creditors are likely underestimating contagion risk, since the possibility of a Grexit is now more likely than before. However, the ECB (particularly after having had various officials, even Draghi, say they could handle a Grexit), they will throw whatever it takes at it to limit market impact.

Regarding the banking system, the ECB has used the threat of removal of the ELA with Ireland and Cyprus to bring them to heel, successfully, and even briefly suspended the ELA with Greece in 2012. Those moves have not led to doubts about the ECB support to other banking systems. If the ECB were to try that with Greece, the government might go the Grexit route. In general, I would expect the demonization of Greece and its government to rise considerably if there were a default, which would facilitate the officials depicting Greece as an unusual outlier case, and one where the actions/reactions would not apply to Eurozone citizens who made an effort to be in good standing.

The efforts of the ECB will backfire. They are seriously underestimating the risks and, what is worse, seriously overestimating the health of the periphery economies. Italy, Spain and Portugal are in a flat course, no matter how much the IMF is trying to inflate the predictions assigning a 3.1% GDP growth to Spain. At this stage of the game we already know how worthy of trust economic predictions of the IMF are, after having seen them miss targets a lot of years. Also, we are seeing more and more than pure financial tools only inflate the bubbles or move them around.

I think that if the institutions force a breakup and grexit this episode will end up in History books together with the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and the invasion of Poland.

Thank you. That’s exactly what I’ve been saying. This entire farce reminds me of both the run up to WWI and the foolish complacency before the fall of Lehman Bros. Both episodes were preceded by foolish talk of “making examples” and how the system could “handle any fallout” because none of the elites involved had a clue as to how brittle the status quo really was.

The ECB is blinkered by short-term thinking. They have convinced themselves that nothing too bad will happen to them over the next 6 months to a year, and that’s what they mean by “they can handle” Grexit. Of course the EU is not going to suddenly collapse if Grexit happens. The Euro will decline towards parity with the dollar perhaps. Greece is a tiny country after all. It’s merely the canary in the coal mine.

But, looking longer term, how can anybody believe that this isn’t a global financial crisis that will have profound and long lasting implications? All the finger pointing in the world is not going to help when the next domino starts to topple, and of course it will since their religious devotion to Austerity will only be enhanced if anything, and Austerity is a death spiral.

Once again Joseph Stiglitz has nailed it:

I have never said that the ECB has not misjudged the risk. I am making a different point, that because the ECB appears to believe its own PR about Grexit risk, it is likely to be very rough with Greece if it gets political cover. I doubt they’d go straight to pushing Greece to the brink but I would not underestimate their willingness to get there over a series of moves.

Oh, there’s no question the other EU countries are going to try and “make the economy scream” to quote Richard Nixon’s infamous order about Chile. But, that is actually going to be suicidal folly politically. The Spanish and other hard-liners are going to be utterly vicious in their attempt to punish Greece, and the Germans will smugly point their fingers at the “lazy Southern Eruos”, but politically, they are going to be stuck with forcing Greece out of the Euro and then crushing their economy and watching Greece turn into a failed state ruled either by the extreme left or the Nazis. It’s not going to be a pretty picture.

It’s not going to be a pretty picture at all, and the lesson the European public learns will not be at all to their liking. I don’t think the Pro-Austerity parties of Spain and Italy are going to win any hearts and minds saying to their own people “see what happens if you try and rebel?!”

Like all idiots who are smugly sure they are smarter than everybody else they can’t see what is obvious – that Austerity is simply not going to sell, that crises are going to continue and that they are slowly losing control of the situation.

They may have the Greek situation “in hand” but they decidedly do not have the political situation in hand at all.

I have a post coming up soon by someone who is looking in detail as to what the implications for Greece are of a default or Grexit. This is from a serious leftist who was actively involved in Occupy and has also studies quite a lot of heterodox economics. He comes to very different conclusions than you do re the negative effects to the Greek economy and society. Now if the immediate contagion is bad enough, yes, agreed, that discredits the hardliners. but you underestimate how much Greece, an economy in the 21st, not 20th century, and in already depressed when the next leg of punishment starts, will suffer.

Those historical events triggered existing security and diplomatic arrangements that had split Europe (Austria-Hungary –> Serbia –> Russia –> Germany –> France–> Britain etc.).

But this seems exactly the opposite from today. What great powers are splitting Europe? Rome, Berlin, and Paris are all part of the euro system. And it’s the Anglo-Americans, not the central Europeans, that are acting twitchy for war with the eastern Europeans.

The EC has been the friendliest party to Greece since the February Eurogroup negotiations.

Have to say Yves, with friends like this, who needs enemies?

They actually have been working to try to get the other creditors to be more moderate, with not much success, since the EC has no checkbook and is thus perceived by the creditors to have no skin in the game. Recall the Moscovici memo in February, in which Moscovici, an EC official, negotiated a memorandum with Varoufakis that he said he was prepared to sign. Varoufakis was understandably shocked when the Eurogroup presented him with a different memo, since Moscovici has not been authorized by the Eurogroup to negotiate on their behalf and apparently Moscovici had not gotten to the Eurogroup in time to tell them what he’d been up to before Eurogroup officials convened with Varoufakis.

The EC is far more worried about Eurozone breakup risk, which also leads them to tell the IMF and ECB to be less bloody-minded.

Also see this incident: http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2015/05/european-commission-tables-proposal-on-greece-to-break-logjam.html

All the forced smiles are rather ridiculous and even grotesque, but to say the EC has been “friendly” to the Greek government is a bit of a stretch. Juncker, in particular, was the former PM and FinMin of Luxemburg, one of the leading money-scrubbing centers of the world, (as witness its inflated per capita GDP), was thus the previous head of the Eurogroup and thus was in the thick of creating the whole mess in the first place, was “elected” EC president by the right-wing grouping in the parliament and, like Schaueble, if closely investigated, probably belongs in jail, (having been forced out of his previous job by a political funding scandal).

I did not say “friendly”. I said “friendliest” which is relative.

‘

And Greeks were acting in accordance with that, running as much of their interaction with the Troika as possible through the EC because they had been their most sympathetic audience.

Did you read the EC trial balloon that the ECB and IMF were so mad about that the EC was forced to deny they had anything to do with it? It pushed for one of the big things Greece has demanded from the very outset, which is to get the negotiations over debt included in the negotiations over the bailout funds.

BTW your comment on Juncker is also ad hominem and thus not germane to his actions re Greece as head of the EC. The onus is on you to prove your assertion, that (up till now when Juncker has decided to wash his hands of Greece) that he was NOT more favorable to their cause and trying to moderate the positions of the IMF and the ECB, and that is also a very low bar?

Moreover, the EC is a much less powerful institution than the ECB and IMF. It would have enhanced Jucnker’s status if he could have brokered a deal between parties that were so far apart. So he had strong personal incentives to try to mollify the creditors as well as Greece.

Your remark is also a classic example of halo effect, a cognitive bias, seeing someone as all good or all bad.

Maybe you and Lambert should brush up on the issue of “ad hominen” arguments. (I was once a philosophy major, so I think I know the matter). They are not always fallacious, but have legitimate uses. The substitution of concealed (attributed) motives, though certainly such can exist, if not reliably knowable), for intentional contents, whether cognitive or practical, would be the point. But pointing to the situatedness of an agent’s intentions is not the same thing. And all the facts I cited are in public evidence and shouldn’t require extra citations, (on a blog comment, after all). And for that matter, using a counter-accusation of ad hominem when such factors are cited in response to an agent’s intentional utterances, is one of the fallacious uses. Accusing me of primitive cognitive bias, might be a case in point, (while you cite Juncker’s ambitions, a motive not in evidence), as if I hadn’t followed these matters closely.

For the record, T. &V.’s diplomatic smiles and lunatic optimism have struck me as equally ridiculous. But I’ve assumed from the get-go that their aim was to be forced into default, if necessary, while keeping their coalition together, rather than being seen to do so “voluntarily”, (hence no signaling capital controls). Whether the crocodile tears are laughter or crying, I’m finding Lapavistas’ position more plausible with each passing day.

Your original argument on Juncker was ad hominem. It was “Juncker has these past job titles, ergo he cannot be trusted to ever to the right thing.” That is logically equivalent to saying that because my work history prior to 2006 was in or related to financial services, I am pro bank.

Juncker’s incentives as EC chief are to maximize turf and the prestige of the institution. An European-level position is a big step up in power and influence from a senior position in a very small country (Luxembourg has all of a bit over a half a million people). He also, based on observable events over the crisis (most important, the Greek government regularly working through the EC in preference to the other members of the Troika) has clearly been “friendlier” than the creditors.

You’ve basically doubled down on your original argument and tried denying an ad hominem attack is ad hom. Your argument is classic ad hom attacking Junckers’s recent conduct based on what your assertions about his character from his prior history. Even people considered to be very vile can do good. The Bulgarian Nazis defied Germany and refused to kill any of their Jews, as one of many examples.

Juncker’s actions re Greece need to be assessed on their own merits. They have still not helped much, but he and Moscovici really have tried to get the IMF and ECB to back off.

Last sentence, penultimate paragraph.

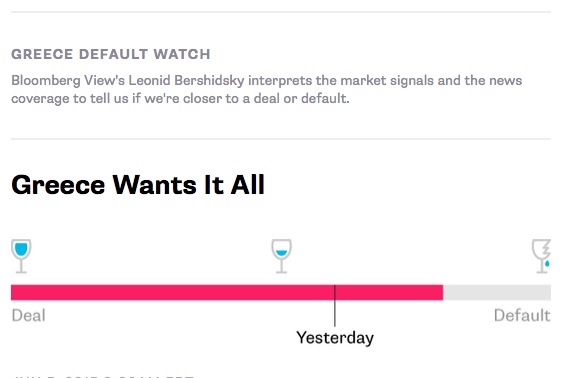

Interesting, this Greece Default Watch. In the post, we see the ultra-big title “Greece Wants It All”.

Today, it’s “Greece Pretends to Negotiate”.

Who is responsible for this ‘Watch’?

The ‘analysis’ by this Leonid guy is basically what his contacts in Berlin say plus this gem:

“Austrian Finance Minister Hans Joerg Schelling said today they aren’t, because the institutions have already made so many concessions that further ones are unimaginable.”

It’s quite obvious he never read the 5-page creditor ‘proposal’ that is supposedly serious, good faith negotiating by the creditors. So the ‘Greeks are the bikers of Europe’ context continues.

Orwell laughs in his grave, and so do I.

You miss that the creditors determine whether Greece gets the money or not, and no money means a Greek default.

Moreover, the creditor proposal, which I have read (and you have no basis for your assertion that Bershidsky has not read it) was explicitly meant as a vehicle that 1. set some stakes in the ground from the creditor side and 2. was designed to elicit a “quick reaction” from Tsipras. It was meant to be at a high level. Tsipras had specifically asked for a discussion to take place on a “political” level and that sort of document is appropriate for that sort of discussion.

You further assume that Bershidsky was responsible for the chart heading. It was an insert in someone else’s article and was likely made by production staff based on the text he provided. You also miss that all the nations of the Eurogroup have to approve any bailout deal. Finally, you bizarrely act as if the table is some sort of diss to Greece, In fact, telling Mr. Market that default risk is greater than they think is actually pro-Greece. Mr. Market getting upset increases pressure on the creditors.

In other words, all you offer is an ad hominem attack. It’s bogus, intellectually lazy, and earns you troll points. See our Policies on this matter.

Contemptuous responses like this one certainly can’t do much to bolster your “we need more comments” cause. Reading the comment in question I think your bar for “troll[ing]” is pretty low. The response would have stood perfectly well on its own without the final paragraph. Just saying.

Apparently the over 300 commenters who left often lengthy and thoughtful comments on the “need more comments” threads (on finance, mind you) don’t agree. So let me respond to what is, in fact, an ad hom, in kind: If your ego is so fragile you’re stewing over a pointed comment from your host, there is very little anyone can do for you. See (

ifsince you have not already) the policy on ad homs.My comment, unlike your hostile and rude reply, contained no ad hominem attack. I’ll simply point out, once again, that unnecessary hostility and name-calling is unlikely to garner more comments or support a constructive dialog.

Then you don’t know what ad hominem means. Rude begets rude. Clever up.

Adding: The Leonid Bershidsky material is an ad hominem. The rest of the material is the equivalent of throwing a drink the face of your host at a party. See the moderation policies.

It does not appear that you read that post carefully. It was not “we need more comments.” It was about the visible level of difference in number of comments that we get on finance/regulatory posts versus political posts and our daily news summaries, and how that creates the impression to the finance, regulatory and legislators who do read those posts that the public doesn’t care and the banks have won the argument. The heated exchanges without exception take place on political posts, where we have never voiced any concern about reader engagement.

Alan, are you in Orwell’s grave or in your own ?

Hi Yves,

Thanks for your great posts on Greece (this one and others).

Although I find myself in opposite political circles (call me a Eurozone Mish) I agree one hundred percent on the “The state of play” that you describe and alas suscribe as well to its pessimistic conclusion:

“It would be better if I were wrong, but this could become even uglier than anyone imagines.”

As our old (nearing 90) Giscard d’Estaing put it, one need to care about a “friendly exit”. Let us not add panic-related sufferings to the sufferings to come. Greece MUST introduce capital controls SOON to reduce capital (what is left of) flight.

it’s ironic that the “hardline leftist” Syriza has negotiated as if it were engaging with deluded pragmatists rather than ideologues who, more importantly, have managed to engineer a broader European political context which reinforces their ideological prejudices.

I’m sure there are concrete reasons why Syriza has proceeded the way it has, but it’s hard not to try to generalize about the instincts and “psychology” of a left political organization who’s core constituency consists of professionals and academics. The basic psychological response of the ‘A’ student towards the “teacher” differ rather drastically from the ‘D’ student and are reinforced by their career path. Regardless of politics, the instinct that we live in a technocracy driven by knowledge and merit is baked into the life aspirations of the professional classes.

It’s often said that the political and financial elites “live in a bubble” but perhaps the walls within which the professional middle-class lives are even more opaque and impermeable.

We do not live in a technocracy driven by knowledge and merit because our nature is incapable of sustaining such a life. Desmond Morris got it right: we are naked apes, and we live in a human zoo.

While I feel like I agree with what you are saying, am confused as to your point. Who is the A-student and who is the D-student in this drama? Which are you saying is being opaque and impermeable? Are you critiquing Syriza’s negotiating style vis a vis the Euro elite? If so, how and how should they be doing so versus an “idealogue” as you posit?

I may have missed a comment on this article, that suggests that Greece may be playing for time:

http://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/varoufakis-ecb-grexit-threat-by-hans-werner-sinn-2015-05

I would like to hear your take on that theory, Yves.

Delay in reaching a resolution may serve the perceived short term interests of both sides. The more I think about the “game” of Greece v. The Troika, the more come to view it is a negative-sum game, in which the objective each side is to stick the other side with the greater burden of an unavoidable huge joint loss. When the day of reckoning comes, there will be bad news for both sides. If so, both sides have incentives to postpone the day of reckoning. According to my belief, nothing in a negotiation will be settled before it has to be.

From the normally Merkel supporting tabloid:

http://www.bild.de/politik/inland/griechenland-krise/es-wird-einsam-um-merkel-41292178.bild.html

More and more CDU MP’s are said to oppose a further “bailout without credible reform agreement”. According to this piece – 29 opposed it, and an additional 109 have voted in Feb for the last package “admit greatest concerns”. The current parliament has 631 MP’s, 311 for CDU 193 SPD, 63 Greens, 64 Lefts…. So there are enough votes around to get it through – but with about 50% of the CDU not supporting their own government?

And even more interestingly, none of the other papers, especially not the serious ones, are reporting anything of this kind….

Varoufakis has expressed the opinion that Greece would be better off in the long run with the drachma. If his game is to reach this outcome, perhaps while remaining in the Eurozone and allowing that Euros are still legal currency, then ‘talking by each other’ is an understatement.

I would guess that Syriza is not so far left that they would view all Greek banks going broke as a positive outcome.

I get the impression that there seems to be agreement that the Creditor demands are, from the Greek government’s viewpoint, politically simply non doable.

Can the same be said about whether or not the demands make any economic sense ?

I gather that NC is skeptical about whether whacking big tax increases in a troubled economy are likely to make the Debtor a more viable Credit Risk.

Where are the European Paul Krugmans in this discussion ? Do such exist and how strong is their influence ?

Heiner Flassbeck supports Greek government views, I guess Stiglitz could also be counted as a “European Paul Krugman”. I don’t know enough about the European economics landscape to assess their influence, though.

http://www.theguardian.com/business/live/2015/jun/10/greece-creditors-reforms-tsipras-merkel-hollande-live

Roger Bootle, the managing director of Capital Economics, believes it’s “only a matter of time” until Greece leaves the euro , and it would be in both sides interest to do so.

“This is an economy where output has fallen by 25% – that is catastrophic, similar to the US Great Depression”, he told Bloomberg TV. ” We’ve seen nothing like it in an advance economy in the second half of the 20th century.”

But doesn’t that prove that Greece must reform its economy, as its lenders demand? Reforms are needed, Bootle agrees, but you simply cannot solve a problem of lack of demand with structural reforms.

” In fact, some of those structural reforms will make the demand problem worse.” (emphasis added)

———————–

But Merkel assures us these kinds of “reforms” are working in Ukraine, so they should good for Greece as well.

Seems like a personal injury lawsuit card game where one side is playing euchre and the other playing bridge, i’ve found yves explanations of this type of negotiating to be educational and insightful

This is a guess, and obviously has no more validity than any other guess. Varoufakis stated directly in his 2012 essay that there is nothing that Greece can do to solve the problems. He stated very specifically that if the EU makes changes those changes will not solve Greece’s problems, it merely gives Greece an opportunity to come up with a solution for their own economy.

This seems to imply that Varoufakis is in favor of some kind of EU collapse that will force them to make necessary changes. At the same time, it’s important that Greece not be blamed for intentionally causing that collapse.

Varoufakis speech in Berlin was pretty straightforward. He simply requested a plan that would allow Greece to grow and to pay back is lawful debts.

That request is unlikely to change anyone’s mind prior to default. Once there is a default Greece is not much worse off than it would be under extreme austerity. At that point while everyone is running in circles trying to blame Greece they are pretty much forced to consider what he actually said.

I agree with your assessment: the Greek government is evaluating the relative costs of austerity plus versus a default, and for them it is pretty obvious that a default on the ECB bonds is the lesser evil unless a very substantial agreement is reached, which does not seem to be coming.

What the institutions offer is a third MoU with more money, and keeping cutting to the bone (to use Varoufakis terms) in exchange for money they don’t want. They are in denial, and, while the Greek government will fight hard to get an agreement, they are not backtracking into austerity.

“Germany reportedly ready to offer Greece a deal”

http://www.theguardian.com/business/live/2015/jun/10/greece-creditors-reforms-tsipras-merkel-hollande-live

Yves, I suppose that you saw Yanis’s tweet this morning linking to an Italian blog quoting Stefano Fassino “if I were Varoufakis I wouldn’t sign the memorandum”… Also implying that some Russian help might be in the wings.

Doesn’t seem helpful to his cause.

I think there are rather simple, uncomplicated explanations for what is going on.

1. Tsipras and his Syriza allies really oppose the creditors’ terms. The current situation of Greece is intolerable, and there is no way out through the “bailout” deal on offer. It only prolongs the depression and leads to the next round of fruitless negotiations, and the next. The Greek government is not following a game-theoretic strategy. It has reached the limit of what it can put on the table, period. Arguably, as Yves and others here have said, their limit was too broad.

2. The creditors believe, with some justification, they have a grip on Greece that extends beyond the current set of arrangements. A “default” is not the same as a writedown, at least not in this case. Greece can miss payments, and the ECB can force them out of the eurozone, as I think likely. But Greece’s economy is so enmeshed with the rest of Europe’s that repayment conditions can be attached to a neverending list of rights and privileges: citizen movement, access to electronic fund transfers and clearing, tariff exemptions and trade access, regulatory approvals, you name it. There will be permanent pressure to repay. Under these circumstances, from a strictly repayment perspective, it makes no sense to give a centimeter.

3. The eurozone is also a political vehicle to facilitate the disembedding of capital, a project that is infeasible at the national level in most European countries where durable social bargains have been struck. This is what the end of national capitalism means in Europe, and why reform always translates to liberalization. Consider the current strike of pharmacists in Greece, resisting the removal of laws that prevented pharmaceuticals from being sold only in pharmacies. This could not have been achieved without strong supranational pressure. And it isn’t happening (yet) in Germany, precisely because no such pressure has been applied. If the demand to liberalize on all fronts can be rejected by a government as exposed to pressure as Greece’s, what’s the point of the entire project?

4. Despite the handwringing I hear, I have no doubt that finance officials in Greece have prepared a rapid transition to a parallel currency which may or may not be the drachma, complete with transitional capital controls. Obviously they cannot publicize this in advance.

5. Default and the introduction of a new currency will be accompanied by at least several months of economic and political chaos. The middle class, whose need for liquidity prevented them from simply squirreling away their assets to a safe location north of the Alps, will be hit hard. There will be intense political polarization, with demonstrations and counterdemonstrations. But no elections are scheduled. (Incidentally, this is one reason why it makes sense for Syriza to hold the line and face the crisis now rather than delay for a year or two.) In the absence of a coup, and assuming that the economic situation stabilizes later this year, Syriza has an excellent chance to emerge from the transition even stronger than before.

6. The only murky point for me has to do with the possibility of a coup. In a period of extreme polarization, it is always possible to make a military invention appear to be a step toward calm, reasonableness and the restoration of democracy. It’s not as though we haven’t seen a number of such coups in the past few years, in places like Honduras, Egypt and Thailand. The question is whether there is a faction willing and able to step in and assume this role. I have absolutely no idea. But if there is, it cannot act without getting a preliminary nod from Europe. Is it conceivable that support for a coup could be part of the punishment meted out by Europe in retaliation for the “irresponsible” behavior of Syriza?

Is it conceivable that support for a coup could be part of the punishment meted out by Europe in retaliation for the “irresponsible” behavior of Syriza?

No, it ain’t. Period.

A Congressional staffer joked to me, “Ins’t the next stage a CIA coup?” I replied, “No, they do that only in countries where the government isn’t popular.” He said, “You’re right. I wonder what they do next.”

My guess is that if the hardliners I call the ultras haven’t already been working on this, they will quickly come up with plenty of idea of how to hurt the Greeks economically that they could justify as necessary post a default measures. Michael Hudson has written about how Germany has been able to conquer Greece with finance rather than through military means. Why change tactics if your current approach is achieving your aims?

Re the ultras, this is interesting:

Ouch, yes, the Netherlands are hardline too, although in the Eurogroup meetings, for the most part, Dijsselbloem has tried to wear his “European leader” hat over his “Dutch Finance Minister” hat. But let us not forget he most assuredly wears that other hat….

Yes, it is surely conceivable that there could be support for a coup in Greece as part of a retaliation meted out by Europe. Just as as there was support for the coup in Ukraine a year and a half ago.

here’s a link for Bloomberg greece default watch, cited above,

http://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2015-greece-default/

it’s back down a bit since events referred to in guardian live blog link

of Edna M. above.

But can the ECB actually force them out of the Eurozone. It’s been published a number of times that there in no mechanism to do so. They can obviously put a lot of pressure on Greece. If it get’s bad enough, everyone in Greece will have to move to Italy. (Just kidding – I think.)

Yes, easily.

They yank the ELA. The only way to prevent a collapse of the Greek banking system is for Greece to impose capital controls and nationalize the banks. The only way to fund the gaping hole in their balance sheets from the withdrawal of ECB support would be to print drachma. While the government can limp along for a while paying employees and pensioners in funny scrip that it can argue has technical features so that it is not a domestic currency, the financial needs or recapitalize the banks and have people willing to do any business with them is to issue drachma to make up for the support from the ECB. It’s a defacto Grexit. De jure is a total mess, that would be improvised on the fly by Eurocrat reactions to events on the ground

Surely anyone in Greece with any sense at all is following this very closely and must be aware that Greek bank deposits are of dubious security in this very unsettled environment. If I were Greek, my mattress would be lumpy indeed with bundles of Euros- is that already happening ? Are Upper Middle Class professionals ( e.g. MDs, DDSs, Engineers etc. ) already starting to move funds ( Euros, of course ) out of the country and seeking new jobs elsewhere ?

The consequences of leaving the Euro to, at least the affluent among the Greeks seem both obvious and severe.

Less obvious to me is the risk entailed by the Creditors intransigence. I read Mr. Soros remarks quoted above and he makes vague ( to me ) reference to non transparent derivatives and credit default swaps.

Exposing my ignorance, I know, but if they are that potentially dangerous, why are they allowed to remain non transparent ?

Another link from today’s Guardian

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2015/jun/09/greece-bailout-talks-the-main-actors-in-a-modern-day-epic

which starts out on the “Greece is almost entirely friendless” meme.

But it strikes me as something of an indication of just how narrow the base of the euro elite has become, and

perhaps a sign of how out of touch they are with large segments of their population, not only in Greece.

I don’t think their reassurances about being able to control side effects of Grexit is too reassuring,

coming as it does from such a narrrow group-think. Maybe they can foresee some short term effects by technical means, but no way they have any very reliable idea, on the level of the larger picture. Maybe their confidence is up insofar as we’ve gotten through 7 years since the big crash without a second catastrophe, surprising enough its true.

There has been no popular response in Europe to countermand the “elite” position. Even Podemos has pointedly said as little as possible about Syriza as possible. For instance, when Pablo Iglesias was in NYC , hea was asked specifically about Syriza and ducked the question. Podemos has also moved to a more centrist position (and did well by it) after having performed much less well than expected in elections in March. So you may not like the “friendless” view, but aside from some well respected heterodox economists like Heiner Fleissbeck, there has been very little evident support for the Greek position in Europe, where austerity and neoliberalism appear to have been well internalized as values.

Thanks for the Heiner Fleissbeck lead.

In fact I think the more serious question is not whether Syriza itself has many friends, but how much support the anti-austerity/neoliberal side has in Europe; in the population at large, and in the elite. If there’s a slight majority of the voting public who will return the same elite to power, but the good-sized minority is left to the wolves, and unable to organize in economic terms, then its an explosive recipe in the long run.

Syriza doesn’t even seem to be in a position to take on the domestic Greek elites; the army and the orthodox church are protected by its coalition partners for now, and probably are untouchable even without them. Oligarchs are protected by the constitution, the bureaucracy etc. I imagine this creates some frustration for their potential friends, and maybe the latter support them best by providing some counterbalancing pressure to take on some domestic interests.

A few observations:

One: ““That’s nonnegotiable,” an EU official said. “What’s been submitted [by Greece] is not a basis for further political discussion.”

If this is the case about Primary Surpluses, as this Euro official is stating, then how was Tsipras misrepresenting the Troika plan when he called it a dirty negotiating trick and a take it or leave it proposal? I didn’t believe Juncker for one minute when he claimed it wasn’t. This official is admitting to it right there.

Two: “They can also sell radical action as necessary to protect the Eurozone from the existential threat of other countries of the Eurozone also departing, that it is necessary to make a Greek default as punitive as possible pour decourager les autres.”

Yves, if you believe this, then does this not encourage Greece to make sure default is as painful as possible for the Euros? That might be why the tone of the Euro official comments seems to be more desperate to me than I’ve seen before. They claim that, ““They do not want a deal with us; they just want debt relief,” and “I don’t think they will move. I think they’re waiting for us to blink, and we won’t.” You said in the post that, “We’ve remarked in the comments section, with a bit of horror and disbelief, that both Varoufakis and Tsipras have said that Greece has until June 30 to get a deal done. ”

But perhaps that is by design. Perhaps, Tsipras and Varoufakis have all along believed default was the only course. So they’ve reasoned that to forestall any punitive actions against Greece post-default, they need to make default as painful as possible. One way to do it would be to blind side the EU by dragging out negotiations as much as possible so that the market , after being lulled to sleep by rumors of deals, will have a sudden terrible realization near the end of the month that default is imminent and swoon uncontrollably. The Greeks might get a better deal through emergency efforts before the clock runs out or they default and force the EU to confront a much larger problem instead of Greece. The larger and messier the default, the more the Euros will have to focus on those market effects and the less able they will be to focus efforts on punishing Greece. They will have too much on their plate to worry about that. As I’ve stated in a previous post, the Greeks have no logical interest in making default as smooth as possible as that only gives its enemies the luxury of time post-default to figure out more imaginative ways of punishing them.

If you had actually read the proposal, the primary surpluses are one section out of five pages. The EU official rejected the counter on primary surpluses. There is no indicator that there were similar informal flat-out rejections of the other area that was reported where Syriza did not move fully to accept the creditor position, that of VAT. Media reports noted that there was a gap, but I have yet to see anyone saying “They can’t negotiate on VAT.” Finally, you also forget that the proposal was offered early in the week, and it was after then that Tsipras didn’t submit his counter on Thursday as he promised, as a result did not meet with Juncker on Friday as planned, and instead gave his angry speech in Parliament. If I were the creditors, my reaction would be “fuck you.” I would harden my position if I thought I had the leverage to do so. So the unwillingness to negotiate primary surplus could be a subsequent decision to punish Tsipras.

Moreover, as we wrote, the Greek have ALREADY largely conceded on primary surpluses (they’ve agreed to keeping primary surpluses, they’ve agreed to the ludicrously high level of 3.5% starting in 2018). From the creditors’ perspective, they’ve already made a huge concession in dropping the 2015 target from 3.0% (what was set in the old memorandum) to 1%, which is the level Syriza had asked for earlier! Syriza may counter that conditions have deteriorated since then, but the retort is that that’s the doing of the current government.

The EU official (who BTW also is not Merkel or Hollande but appears to be representing the now pissed-off EC point of view) is also not Merkel or Hollande. Tsipras did move negotiations to a political level. That gambit is not working out as he hoped as the politicians are taking a harder line, the reverse of what he expected to happen.

Ok, so I think I understand what you are saying regarding the take it or leave it accusation, but correct me if I’m wrong. You’re saying that the primary surplus issue is take it or leave it, but that the other areas are negotiable and from that stand point, the entirety of the proposal is NOT take it or leave it. Is that what you’re saying?

Also, what about my point about default? Does not the hardline Euro approach beg Greece to make default a much larger, messier, worse event?

We don’t know what the creditor position is since they are grappling with what to do after the Tsipras speech. The memo from them was meant to show that they wanted to bring matters to a close and make clear to Greece that they weren’t prepared to give much, that the politicians were backing the position of the technical teams. Tsipras escalated by dropping the negotiations and giving the speech in Parliament instead. So it is impossible to tell whether that EU official remark was where things stood as of when the memo was sent to Tsipras, or the hardening is a creditor tit for tat.

I don’t see how Greece can take unilateral action at this stage to make a default any messier than it will already be. And if they do, they are going into a default in the worst position possible, with no capital controls in place and having stripped every cupboard bare that they could find to pay the creditors.

In fairness, I did not take the time to cite sources, plus some of the financial press (which is really prone to simplification and exaggeration) was presenting the creditor offer as take it or leave it.

Like it or not, Peter Spiegel at the FT has the best contacts in Brussels, and he is also very clear about his sourcing (as to whether a tidbit is from., so one can judge the integrity of his accounts much better than with other reporters on this beat). The Eurocrats actually seemed concerned about media reports that the creditor offer would be all-or-nothing, (recall it took a couple of days to work it up).

From Spiegel on June 1:

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/433612d4-08a1-11e5-b38c-00144feabdc0.html

Now reading between the lines, the creditors were presumably flummoxed by Tripras continuing to insist a deal was nigh. I’d be concerned whether this was just messaging to slow the bank run and bolster domestic support, or whehter he actually believed it. And I’d also wonder it mixed messages from the creditors (EC v. IMF) had made him unduly hopeful. So I read this as, “Look, this is what it we need to do a deal.” That may sound like a distinction without a difference (versus “take it or leave it”) but the fact that Juncker was waiting for a counteroffer on Thursday and was prepared to continue negotiating on Friday says that document was at least somewhat negotiable, even it not very much. And we’ll never know how much now that conditions have changed.

From Siegel today:

http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/853d6af2-0fc6-11e5-94d1-00144feabdc0.html

OK, but how much of this do you think poor messaging on the part of the ECB/EU/Troika? I think too much is placed upon Tsipras without looking at the other side. Most of the time, they appear to be trying to out-hardline each other, as in “I’m tougher on Greece than you are.” So why should Tsipras assume there is any wiggle room on any aspect of a proposal when the other side is constantly shooting down alternatives put forward and various officials make negative noises about anything other than what has been put forward heretofore? I know from my own impression of these reports is that Greece is only to agree or disagree, not negotiate. Like some sort of supplicant. That’s what I’m getting from every week of these supposed talks. They have themselves to blame if that is not the impression they were trying to give. That’s why I believe Tsipras gave no counterproposal. He took them at what he believed was their word from the impressions they gave and so he said “screw it” I’m not giving another inch.

As for the creditors now saying they are getting more hardline, perhaps that is where they always were. All of this he said/he said about proposals and counterproposals WAS in fact theater all along to make the Troika look reasonable and Tsipras just didn’t feel like playing that game any longer.

The creditors have insisted on certain structural reforms like labor reforms, That is an outtrade. On other topics, there position generally is “you can propose reforms as long at the math adds up.” The Greeks have been overly optimistic (per the creditors) re how quickly they can implement and get benefits from stuff like improving tax collections. I have to tell you, based on some of the timing I’ve seen the Greeks assume v. how long I’ve been it to get programs designed and rolled out in well ordered large organizations (bank clients), the creditors aren’t incorrect.

The problem is more broadly seem that Varoufakis seems to have assumed that he could fudge the primary surplus numbers because that was all down the road, so conceding those was not a big loss. But the creditors are insisting on having “realistic” programs embedded in the proposals and presumably getting those enshrined in legislation. I don’t think the Greek side was expecting that. That’s really a huge lapse, since it would not be hard to find out from their advisor Lazard how these negotiations normally go.

More on pensions: It has been said some days ago here in a comment, that retired Greek citizens get 600 a month.

Here are some other figures from today’s ruling of a Greek court. Aside from the question of “affordability”, why the higher pensions (over 2000 Euro per month) should get a 15 % increase (starting now) is exactly why the pension question angers the people of the creditor countries.

And as is stated right here, almost a million Greeks have pensions higher than 1000 a month.

http://www.ekathimerini.com/4dcgi/_w_articles_wsite1_1_10/06/2015_550910

“The ruling affects some 800,000 pensioners who earned more than 1,000 euros a month.

It is estimated the decision will lead to pensions between 1,000 and 1,500 euros rising by 5 percent, those between 1,500 and 2,000 increasing by 10 percent and those over 2,000 seeing a rise of 15 percent.”

Yves seems to imply that a default is a negative, whereas I view it as a crucial step forward.

All this dooming ring over what would happen to Greece after a default is colouring all of Yves’s commentary IMO. The truth is that no one knows how much Greece will suffer after default and it would be wise to be cautious in pronouncements on this issue. No less a figure as Bill Mitchell has called for a default and exit as Greece’s best course of action.

The main reason I think a default will be good is that the TINA/austerity mythos MUST be punctured if there is to be any positive future for Europe. This is the time to puncture it. No doubt, Greece will suffer in the short term, but it has already suffered disproportionately.

Malaysia told the IMf to go F&&& themselves, Iceland took an independent course and Argentina recovered well after a period of suffering. All of these situations are different and not directly comparable to Greece, but none of these countries are failed states and all of them defied the international powers that be to one degree or another.

It gives me hope that Greeks can survive defiance without becoming a European version of Haiti.

The stakes are high: the principle of democratic self-determination is at stake. Capitulation equals the continued enslavement of a people at the hands of an international elite.

In big-picture terms this whole thing isn’t really about Greece at all. It’s about the inevitable outcome of a system based on Ponzi economics. Greece is only the weak link in the chain. Even if by some miracle Greece can be saved from default, the next such crisis will arise soon after, in some other country.

What counts in this world are resources, both human and natural and it’s high time for the world to return to a resource-based rather than a money-based economy.

Once upon a time the Spanish believed all their problems could be solved by the accumulation of gold. But their gold was only as good as what could be purchased with it. Triillions of dollars have accumulated in the world of today, but it’s all bullshit. Greece is a real treasure, and nothing will change that. All the money is just dead weight.