Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. This is a detailed account of the long and tortured history of budget fakery in Greece and how it is has been aggressively defended by successive Greek governments. A tidbit from the post: one section is labeled “When revising wrong statistics is treason.”

By Sigrún Davídsdóttir, an Icelandic journalist, broadcaster and writer. Her coverage of Iceland’s financial crisis and subsequent recovery can be found at her Icelog. Together with Professor Þórólfur Matthíasson she has earlier written at A Fistful of Euros on what Icelandic lessons could be used to deal with the Greek banks. Cross posted from Coppola Comment

The word “trust” has been mentioned time and again in reports on the tortuous negotiations on Greece. One reason is the persistent deceit in reporting on debt and deficit statistics, including lying about an off market swap with Goldman Sachs: not a one-off deceit but a political interference through concerted action among several public institutions for more then ten years.

As late as in the July 12 Euro Summit statement “safeguarding of the full legal independence of ELSTAT” was stated as a required measure. Worryingly, Andreas Georgiou president of ELSTAT from 2010, the man who set the statistics straight, and some of his staff, have been hounded by political forces, including Syriza. Further, a Greek parliamentary investigation aims to show that foreigners are to blame for the “odious” debt. But there is no effort to clarify a decade of falsifying statistics.

In Iceland there were also voices blaming its collapse on foreigners. But the report of the Special Investigation Committee silenced these voices. As long as powerful parts of the Greek political class are unwilling to admit to past failures it might prove difficult to deal with the consequences: the profound lack of trust between Greece and its creditors.

“This is all the fault of foreigners!”

In Iceland, this was a common first reaction among some politicians and political forces following the collapse of the three largest Icelandic banks in October 2008. Allegedly, foreign powers were jealous or even scared of the success of the Icelandic banks abroad or aimed at taking over Icelandic energy sources. In April 2010 the publication of a report by the Special Investigation Committee, SIC, effectively silenced these voices. It documented that the causes were domestic: failed policies, lax financial supervision, fawning faith in the fast-growing

banking system and thoroughly reckless, and at times criminal, banking.

As the crisis struck, Iceland’s public debt was about 30% of GDP and it had a budget surplus. Though reluctant to seek assistance from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) the Icelandic government did so in the weeks following the collapse. An IMF crisis loan of $2.1bn eased the adjustment from boom to bust. Already by the summer of 2011 Iceland was back to growth and by August 2011 it completed the IMF programme executed by a left government in power from early 2009 until spring 2013. Good implementation and Iceland’s ownership of the programme explains the success. For Ireland it was the same: it entered the crisis with strong public finances and ended a harsh Troika programme late 2013. Ireland’s growth in 2014 was 4.8%.

For Greece it was a different story. From 1995 to 2014 it had an average budget deficit of 7%. Already in 1996, government debt was above 100% of GDP, hovering there until the debt started climbing worryingly in the period 2008 to 2009 – far from the prescribed Maastricht criteria of budget deficit not exceeding 3% and public debt no higher than 60% of GDP. But Greece’s chronically high budget deficit and public debt had one exception: both figures miraculously dived, in the case of the deficit number to below the Maastricht limit, to enable Greece to join the Euro in 2001.

Greece had an extra problem not found in Iceland, Ireland or any other crisis-hit EEA countries. In addition to dismal public finances for decades there is the even more horrifying saga of deliberate hiding and falsifying economic realities by misreporting the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) and hiding debt and deficit with off market swaps.*

This is not a case of just fiddling the figures once to get into the Euro but a deceit stretching over more than ten years involving not only the National Statistical Service of Greece (NSSG) but the Greek Ministry of Finance (MoF), the Greek Accounting Office (GAO) and other important institutions involved in the compilation of EDP deficit and debt statistics – in short, the whole political power base of Greece’s public economy.

2004: The First Greek Crisis of Unreliable Statistics

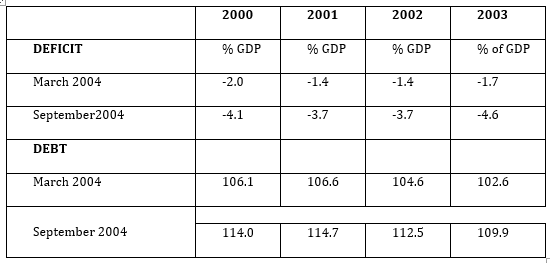

The first Greek crisis did not attract much attention although it was indirectly a crisis of deficit and debt. It was caused by faulty statistics, already unearthed by Eurostat in 2002. Eurostat’s 2004 Report on the revision of the Greek government deficit and debt figures rejected the original figures put forward by the Greek authorities. After revision the numbers for the previous years looked drastically different – the budget deficit, which should have been within 3%, moved shockingly:

The institutions responsible for reporting on the debt and deficit figures were NSSG, the MoF through the GAO as well as MoF’s Single Payment Authority and the Bank of Greece. Specifically, NSSG and the MoF were responsible for the deficit reporting; the MoF was fully responsible for the debt figures.

Eurostat drew various lessons from the first Greek crisis. Legislative changes were made to eradicate the earlier problems – not an entirely successful exercise as could be seen when the same problems re-surfaced. But the most important result of the 2004 crisis was a set of statistical principles known as the European Statistics Code of Practice, which was adopted in February 2005 and revised in September 2011 following the next Greek crisis of statistical data. Unfortunately, NSSG drew no such lessons.

2009: The Second Greek Crisis of Unreliable Statistics

Following the 2004 report, Eurostat had NSSG in what can best be described as wholly exceptional and intensive occupational therapy. Of the ten EDP notifications 2005-2009 Eurostat expressed reservations about five of them, more than for any other country. No country other than Greece received “methodological visits” from Eurostat. The Greek notifications which passed did so only because Eurostat had corrected them during the notification period, always increasing the deficit from the numbers originally reported by the Greek authorities.

But in spite of Eurostat’s efforts the pupil was unwilling to learn, and in 2009 there was a second crisis of statistics. In January 2010, a 30-page report on Greek Government Deficit and Debt Statistics from the European Commission bluntly stated that things had not improved. In fact what had been going on at Greek authorities had no parallel in any other EU country.

This second crisis of Greek statistics in 2009 was set off by the dramatic revisions of the deficit forecast for 2009. As in 2004, this new crisis led to major revisions of earlier forecasts: the April forecast was revised twice in October. What happened between spring and October was that George Papandreou and PASOK ousted New Democracy and prime minister Kostas Karamanlis from power. The new government was now beating drums over a much worse state of affairs than the earlier data and forecast had shown.

After first reporting on October 2nd 2009, NSSG produced another set of figures on October 21st which revised the earlier reported deficit for 2008 from 5% of GDP to 7.7% and the forecasted deficit for 2009 from 3.7% of GDP to 12.5% (as explained in footnote, numbers for current year are a forecast, whereas numbers for earlier years should be actual data).

This was not all. In early 2010, Eurostat was still not convinced about the actual EDP data from the years 2005 to 2008. The earlier 2009 deficit forecast of 12.5% had risen to an actual deficit of 13.6% by April 2010. The final figure was confirmed as 15.4% in late 2010.

The European Commission’s report detected common features with events in 2004 and 2009: a change of government. In March 2004, Kostas Karamanlis and New Democracy came to power, ending eleven years of PASOK rule; in October 2009, George Papandreou and PASOK won back power. The EC noted that in both cases:

substantial revisions took place revealing a practice of widespread misreporting, in an environment in which checks and balances appear absent, information opaque and distorted, and institutions weak and poorly coordinated. The frequent missions conducted by Eurostat in the interval between these episodes, the high number of methodological visits, the numerous reservations to the notifications of the Greek authorities, on top of the non-compliance with Eurostat recommendations despite assurances to the contrary, provide additional evidence that the problems are only partly of a methodological nature and would largely lie beyond the statistical sphere.

In other words, the problem was not statistics but politics. As politics is well outside its remit, Eurostat could not get to the core of the problem:

Though eventually an overall level of completion was achieved, given that Eurostat is restricted to statistical matters in its work the measures foreseen in the action plan were mainly of a methodological nature, and did not address the issues of institutional settings, accountability, responsibility and political interference.

Political interference could be deduced from the fact that reservations expressed by Eurostat between 2005 and 2008 on specific budgetary issues, which had then been clarified and corrected, resurfaced in 2009 when earlier corrections were reverted and the figures were once more wrong.

Good Faith versus Fraud

The EC’s 2010 report identified two different but in some cases linked sets of problems. The first was due to methodological weaknesses and unsatisfactory technical procedures, both at the NSSG and the authorities that provided data to the NSSG, in particular the GAO and the MoF.

The second set of problems stemmed:

from inappropriate governance, with poor cooperation and lack of clear responsibilities between several Greek institutions and services responsible for the EDP notifications, diffuse personal responsibilities, ambiguous empowerment of officials, absence of written instruction and documentation, which leave the quality of fiscal statistics subject to political pressures and electoral cycles

Eurostat’s extra scrutiny and unprecedented effort had clearly not been enough:

even this activity was unable to detect the level of (hidden) interference in the Greek EDP data. In particular, after the closure of the infringement procedure at the end of 2007, Eurostat issued a reservation on the quality of the Greek data in the April 2008 notification and validated the notifications of October 2008 and April 2009 only after it intervened before and during the notification period to correct mistakes or inappropriate recording, with the result of increasing the notified deficit in both instances. As an example, Eurostat’s methodological missions in 2008 resulted in an increase of the 2007 deficit figure notified by the Greek authorities, from 2.8% to 3.5% of GDP.

The EC’s report further pointed out that:

on top of the serious problems observed in the functioning of other areas involved in the management of Greek public revenues and expenditures, that are not the object of this report, the current set-up does not guarantee the independence, integrity and accountability of the national statistical authorities. In particular the professional independence of the NSSG from the Ministry of Finance is not assured, which has allowed the reporting of EDP data to be influenced by factors other than the regulatory and legally binding principles for the production of high quality European statistics.

The EC concluded that there was nothing wrong with the quality assurance system in place at Eurostat. The shortcomings were peculiar to Greece:

The partners in the ESS (European Statistical System) are supposed to cooperate in good faith. Deliberate misreporting or fraud is not foreseen in the regulation.

And the rarity of revisions of such magnitude was underlined:

Revisions of this magnitude in the estimated past government deficit ratios have een extremely rare in other EU Member States, but have taken place for Greece on several occasions.

The EC’s report spells out the interplay between authorities, dictated by political needs. Against these concerted actions by Greek authorities, the efforts of European institutions were bound to be inadequate. “The situation can only be corrected by decisive action of the Greek government,” the report said.

The Goldman Sachs 2001 Swaps – Part of the Greek Statistics Deceit Saga

In early 2010, international media was reporting that Greece had entered into a certain type of swap – off market swaps – with Goldman Sachs in 2001 in order to bring its debt to a certain level so as to be eligible for euro membership

In Council Regulation (EC) No 2223/96 swaps were classified as “financial derivatives,” with a 2001 amendment making it clear that no “payment resulting from any kind of swap arrangement is to be considered as interest and recorded under property.” However, at that time off market swaps were not much noted. By the mid-2000s it became evident that the use of off market swaps could have the effect of reducing the measured debt according to the existing rules. Eurostat took this into account and issued guidelines to record off market swaps differently from regular swaps. Further, Eurostat rules specify that when in doubt national statistical authorities should ask Eurostat.

In 2008, Eurostat asked member states to declare any off market swaps. The prompt Greek answer was: “The State does not engage in options, forwards, futures or FOREX swaps, nor in off market swaps (swaps with non-zero market value at inception).”

In its Report on the EDP Methodological Visits to Greece in 2010, Eurostat scrutinised the 2001 currency off-market swap agreements with Goldman Sachs, using an exchange rate different from the spot prevailing one that the Greek Public Debt Agency (PDMA) had made with the bank. It turned out that the 2008 answer was just the opposite of what had happened: the Greek state had indeed engaged in swaps but kept it carefully hidden from the outer world, including Eurostat.

After having been found to be lying about the swaps, Greek authorities were decidedly unwilling to inform Eurostat about their details. Not until after the fourth Eurostat visit, at the end of September 2010 – after Andreas Georgiou took over at ELSTAT – did Eurostat feel properly informed on the Goldman Sachs swap.

The GS off market swaps were in total thirteen contracts with maturity from 2002 to 2016, later extended to 2037. As Eurostat remarked, these transactions had several unusual aspects compared to normal practices. The original contracts have been revised, amended and restructured over the years, some of which have resulted in what Eurostat defines as new transactions.

The GS swaps hid a debt of $2.8bn in 2001; after later restructuring the understatement of the debt was $5.4bn. The swap transaction, never before reported as part of the public accounts, was part of the revisions in the first ELSTAT reporting after Georgiou took over. This actually increased the deficit by a small amount for every year since 2001, as well as increasing the debt figure.

The swap story is a parallel to the Greek data deceit in the sense that it was not a single event but a deceit running for years, involving several Greek authorities. Taken together, both the swap deceit and the faulty reporting of forecasts and statistics by Greek authorities show a determined and concerted political effort to hide facts and figures, which did not change when new governments came to power.

A Thriller of Statistical Data and Mysteriously Acquired Emails

The Greek economy deteriorated drastically following the financial crisis in 2008. Public debt was at 129% of GDP by the end of 2009. The country effectively lost market access in March 2010. With an agreement signed on May 2nd, 2010, Greece became the first Eurozone country to be bailed out. The messy statistics made the negotiations tortuous.

After the appalling failures, misrepresentations and direct manipulation of figures for political purposes, things turned for the better when Andreas Georgiou took over as president of the newly established ELSTAT in August 2010. However, not everyone in the Greek political system celebrated the fact that ELSTAT was now operating strictly to ESS standards.

By the time Georgiou took over most of the corrections of earlier figures had already been done under the auspice of Eurostat. There was however the last set of corrections of deficit and debt figures. As pointed out earlier, the GS off market swaps were included for the first time, changing figures for earlier years, and the actual deficit figure for 2009 was yet again revised upward in the first set of data delivered by Georgiou.

The adoption of the new statistics law in March 2010 made ELSTAT independent of the MoF, although its board was politically appointed in addition to a representative from the employees’ union. This might not have been a problem if the board had understood the European Statistics Code of Practice in the same way as Georgiou.

Georgiou emphasised the independence and accountability of ELSTAT, and thought the board should be involved only with the broader issues, not the statistical production process. But the board felt, among other things, that it should vote on and approve the statistics and saw Georgiou as being manipulative, wanting to rule over the statistics. Three of the members of the new board, set up in August 2010 – ELSTAT’s vice president Nikos Logothetis, Zoe Georganda and Andreas Philippou – had applied for the position of president of ELSTAT, which possibly did not make things easier.

The breakdown of trust happened at a meeting with the presidium of the employees’ union on 21st October 2010, after Georgiou had been in office less than three months. At this meeting, the presidium showed Georgiou a document – a legal opinion from Georgiou’s lawyer, with whom Georgiou had been in touch via his private email account, on issues related to the law on ELSTAT that was in the process of being changed. Georgiou realised that someone had unauthorised access to his account. He later discovered that another member of the board, Zoe Georganda, possessed an email Georgiou had exchanged with Poul Thomsen, head of the Greek IMF mission.

Georgiou brought the case to the police, who discovered that Nikos Logothetis had been entering Georgiou’s account from the first day Georgiou took up his position at ELSTAT. When the police did a house search, Logothetis was actually at his computer, logged into Georgiou’s account. After less than six months in office Logothetis resigned from the ELSTAT board in February 2011 as criminal charges, based on his hacking into Georgiou’s account, were brought against him.

Logothetis has denied accessing the account and claims instead that various leading European statisticians framed him. His case is pending in court. But in spite of being charged with unauthorised access to Georgiou’s account, Logothetis has repeatedly been called in as an expert witness in parliament in the cases against Georgiou and his two colleagues.

When Revising Wrong Statistics is Treason

In September 2011, Antonis Samaras, the newly elected leader of New Democracy and minister for culture, gave a speech at the Thessaloniki International Expo in which he attacked George Papandreou, accusing him of manipulating statistics on coming to power in autumn 2009. Samaras claimed that Papandreou had done this to discredit Kostas Karamanlis, who had lost the election that brought Papandreou to power and whom Samaras had succeeded as party leader. This speech proved fateful, not for Papandreou but for ELSTAT’s president Andreas Georgiou.

A few days after Samaras’s speech, Georgiou was called to the parliament to explain why he had ignored national interests and revised the figures upwards. Georgiou referred to the ESS Code of Practice but gained little understanding. Instead he was accused of inflating the 2009 figures under instruction of Eurostat to push Greece into the Adjustment Programme. This ignored the fact that the main corrections had been done before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT.

It is important to keep in mind the context for the 2009 deficit: there was the forecasted deficit of 3.9%, put forth by the MoF and reported by NSSG in April 2009, and then the estimate of the actual 2009 deficit of 13.6%, as reported by NSSG in April 2010. All of this had happened before Georgiou took over at ELSTAT in August 2010, after which the final adjustment from 13.6% to 15.4% was made.

The accusations against Georgiou also ignored the fact that Greece had entered the Adjustment Programme three months before he took over at ELSTAT and also that the Greek statistical data had been found to be wrong prior to 2000, up to 2004 and then again up to end of 2009. Political figures on left and right of the political spectrum united against the ELSTAT president as if the only reason for the country’s high debt and deficit were statistics. The Greek Association of Lawyers accused Georgiou of high treason.

Around the time of the hearing in parliament in September 2011, a prosecutor took up the case against Georgiou and two ELSTAT managers and eventually pressed criminal charges in January 2013. In accordance with due process, an investigating judge began a more thorough investigation but at its conclusion, almost two years later, in August 2013 recommended that the case be dropped as nothing was found to merit taking the case further. Following interventions by politicians the case was kept open by the judicial system.

Twice again—in 2014 and 2015—prosecutors proposed that the case be dropped, always followed by interventions from nearly all sides of the political spectrum, which insisted on charges of false statements on the 2009 deficit and debt, and breach of faith against the state/causing the state damages be sustained and that the case be taken to trial. As the punishment should be relative to the damages, calculated to amount to €171bn, this would effectively have amounted to a prison sentence for life.

The charges against Georgiou and the two ELSTAT managers for allegedly making false statements on the 2009 statistics and breach of faith have recently been dropped. However, charges against Georgiou, inter alia for alleged violation of duty by not bringing the 2009 figures to the former board for voting, are being upheld. Some members of that former board still insist that the actual deficit figure of 2009 turned out to be identical to the planned deficit figure for 2009 of 3.9%, put forward in April 2009

Truth Commissions and ELSTAT

One of the measures agreed on by the Eurogroup and Greece after the fateful Euro Summit July 12, “(g)iven the need to rebuild trust with Greece,” was “safeguarding of the full legal independence of ELSTAT.” This reflects the fact that ELSTAT’s independence is still not secured and ELSTAT’s president still under attack.

The Greek parliament has set up two committees to investigate the past. One is the Parliamentary Truth about the Debt Committee, which was set up in April 2015, with members chosen by the Syriza president of the Greek parliament Zoe Konstantopoulou. The other, a Parliamentary Investigative Committee made up of members of parliament and normally referred to as the Investigative Committee about the Memoranda, is scrutinising how Greece got into the two Memoranda of Understanding with international partners, in 2010 and 2012, in the context of adjustment programs.

The two committees both seem to be in denial regarding the swaps and the faulty statistics. Both uphold blaming and shaming Georgiou and the two ELSTAT managers. In the Truth about the Debt Commission’s preliminary findings the earlier claims against Papandreou’s government are again taken up:

George Papandreou’s government helped to present the elements of a banking crisis as a sovereign debt crisis in 2009 by emphasizing and boosting the public deficit and debt.

And the Commission concludes:

Greece not only does not have the ability to pay this debt, but also should not pay this debt first and foremost because the debt emerging from the Troika’s arrangements is a direct infringement on the fundamental human rights of the residents of Greece.Hence, we came to the conclusion that Greece should not pay this debt because it is illegal, illegitimate, and odious.

A former director of the national accounts division at NSSG and now at ELSTAT (but heading a different division), Nikos Stroblos, who has accused Georgiou and the two others of manipulating statistics on instructions from Eurostat, is one of the contributors to the preliminary report of the Truth about the Debt Committee and has given evidence to the Investigative Committee on the Memoranda.

As recently as June 18, Nikos Logothetis – he of the aforementioned email hacking – testified before the Committee about the Memoranda, claiming that the deficit figures for 2009 and 2010 had been deliberately and artificially inflated. He called Georgiou a “Eurostat pawn” who had used tricks to increase the deficit figure.

Remarkably, the Greek parliament has never questioned anyone on the tricks and manipulations going on at ELSTAT and other public institutions involved in reporting wrong data from before 2000 until 2010.

International Support for ELSTAT Managers

Contrary to the sustained attacks at home, Georgiou and the two managers have enjoyed the support of Eurostat, European and international associations of statisticians, reflecting the fact that under Georgiou ELSTAT’s reporting has fully complied with Eurostat standards.

In late May this year, the European Statistical System (ESS) published a statement

expressing concern regarding the situation in Greece:

the statistical institute, ELSTAT, as well as some of its staff members, including the current President of ELSTAT, continue to be questioned in their professional capacity. There are ongoing political debates and investigatory and judicial proceedings related to actions taken by ELSTAT and to statistics which have repeatedly passed the quality checks applied by Eurostat to ensure full compliance with Union legislation.

On June 12 2015 the International Statistical Institute (ISI) published its fourth statement regarding the situation in Greece, welcoming the proposal from the Greek Appeals prosecutor that judicial authorities drop the investigation into claims that the current head of ELSTAT, Andreas Georgiou, inflated the country’s public deficit figure for 2009. ISI pointed out that according to the prosecutor the probe into Georgiou and the two managers had not delivered any evidence suggesting that the three had manipulated the figures. ISI repeated its statement from 2013:

the charges against Mr. Georgiou and two of his Managers of exaggerating the estimates of Greek government deficit and debt for the year 2009 are fanciful and not consistent with the facts’… The ISI expresses the hope that justice will prevail in this case and that the threat of prosecution will finally be lifted from Mr Georgiou and his Managers.

These recent statements on ELSTAT, and the reiterated requirement for ELSTAT independence in the Euro Summit’s statement of July 12th 2015, show that political pressure on ELSTAT is still palpable.

The Lethal Blend of “Unhealthy Politeness” and “Excessive Deference”

The lack of scrutiny, as demonstrated in the saga of the faulty Greek statistics, can partly be blamed on the European powers. True, both Eurostat and then the European Commission did exhume the ELSTAT failures and misreporting; but that it could happen in the first place is also due to failures at the European level.

When the European Union created a single currency the Euro countries in effect embarked on a journey all on the same ship. By now, it is evident that the crew – the European authorities – did not have the necessary safety measures to keep discipline among the passengers. Nor have the passengers kept an eye on each other. In the summer of 2011, Mario Monti, sorely tried by his experience as EU Commissary, formulated what had gone wrong:

At the root of the eurozone crisis lies of course the past indiscipline of specific member states, Greece in the first place. But such indiscipline could simply not have occurred without two widespread failings by governments as they sit at the table of the European

Council: an unhealthy politeness towards each other, and excessive deference to large member states.

A successful monetary union demands more than the countries being just fair-weather friends. The crisis countries, most notably Greece, can only learn from the past if they understand what happened. In Greece these failures were, among others, the basic function in a modern state of truthfully reporting statistics.

Truth or Politically Suitable Truth

In December 2008, while Iceland was still in shock after the banking collapse, its parliament set up a Special Investigation Committee, SIC, which operated wholly independently of parliament. The three SIC members were Supreme Court Justice Páll Hreinsson (the chairman), Parliament’s Ombudsman Tryggvi Gunnarsson and lecturer in economics at Yale University Sigríður Benediktsdóttir. Together, they supervised the work of about 40 experts. Their report of 2600 pages was published on April 10th 2010.

The report buried politically-motivated explanations of the collapse being caused by foreigners and instead recounted what had actually happened, based on both documents and hearings (private, not public hearings). One benefit of the SIC report is that no political party or anyone else can now tell the collapse saga as suits their interest: the documented saga exists and this effectively ended the political blame game. Importantly, the report points out lessons to learn.

Sadly, nothing similar has been done in Greece. The two committees set up by the Greek parliament do not seem entirely credible, because the allegations of ELSTAT misconduct and manipulation under Georgiou are being recycled. Further, their scope seems myopic, as no effort is made to explain what went on at the institutions that from before 2000 until 2010 were reporting faulty statistics and forecasts and lying about the GS swaps.

All of this taken together shows a political class, including within Syriza, not only unwilling to face the past but actively fighting any attempt to clarify things in a battle where even national statistics are a dangerous weapon. The fact that leading Greek political powers are still fighting the wrong fight on statistics is unfortunately symptomatic of political undercurrents in Greece. And this, in part, explains why the Troika and the EU member states find it so hard to trust Greece.

*A note on EU statistics: twice a year, before end of March and August, statistical authorities in the EU countries report forecasts of debt and deficit numbers for the current year, i.e. what the planned deficit and debt is and then statistical data for earlier years, i.e. the real debt and deficit, according to strict Eurostat procedure, in order to produce comparable statistics. This reporting, called Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP) is published by Eurostat in April and October every year.

Image from Jubilee Debt Org