Yves here. Recall that the S&P threat to downgrade US debt, which was widely depicted as a “meteor will hit the planet and wipe out the dinosaurs” level event. We were among the small minority that regarded the scaremongering as overdone and also pointed out that a political agenda was at work. This is a section of our discussion in 2011:

If you look at the S&P statement, it’s not a ratings judgment, it’s a long form political op ed. I suppose I should not be surprised, since the NRSRO’s “get out of liability free” card is that their ratings are mere journalistic opionion. As Robert Reich tartly observed:

If we pay our bills, we’re a good credit risk. If we don’t, or aren’t likely to, we’re a bad credit risk. When, how, and by how much we bring down the long term debt — or, more accurately, the ratio of debt to GDP — is none of S&P’s business.

Jane Hamsher highlights the hypocrisy of the S&P rating, since it shifted from its 2010 rationale of demographic stress to a February 2011 focus on entitlements. And it didn’t bat an eye at the $2.6 trillion deficit-increasing Bush tax cut extension at year end 2010. More from Hamsher:

Neither Moody’s nor Fitch downgraded US debt at this time. And S&P can’t quite come up with a consistent answer about why they are out there by themselves. It’s like they looked at a public opinion poll, decided that there was no way anyone would argue with “partisan bickering” as a justification, and crossed their fingers that nobody would actually question what it is that they were justifying.

S&P is playing footsie with the Republicans, who are passing bills to relieve them of the legal liabilities that Dodd-Frank exposes them to — even as the SEC is investigating S&P for fraud in the mortgage meltdown.

Some said that S&P wouldn’t dare downgrade the US debt. But it was all over four days ago when Pimco’s Mohammed El-Erian said that S&P was “under pressure” on the US rating.

If you didn’t happen to catch Devan Sharma’s testimony before the House Financial Services Committee last week, this was what he said:

As Dodd-Frank rulemaking progresses, we believe it is critical that new regulations preserve the ability of NRSROs to make their own analytical decisions without fear that those decisions will be later second-guessed if the future does not turn out to be as anticipate or that in publishing a potential controversial view, they will expose themselves to regulatory retaliation.

Pressures of that sort could only undermine the significant progress we believe has been made over the years by rating agencies and regulators alike to provide the market with transparent, quality and generally independent views about the credit-worthiness of issuers and their securities. I thank you for the opportunity to participate in the hearing and I would be happy to answer any questions you may have.

“Pressure.”

That’s what Rep. Randy Neugebauer, chairman of the House Financial Services Subcommittee said on April 29, when he requested documents from the administration: Treasury officials “may have exerted too much pressure on S&P.” The Republicans were already laying the tracks for S&P’s defense in April.

Here are a few more dots to connect the timeline:

April 18: Mitt Romney: “The Obama presidency was downgraded today.”

April 20: Mitt Romney: “Standard & Poor’s, one of the rating agencies, just downgraded their view of the future for America…If you will, they downgraded the Obama presidency.”

July 15: WSJ — “The Obama downgrade.”They’ve been cooking this one for a while. S&P will defend themselves from the accusation of overt partisan manipulation by claiming the Treasury “pressured” them not to downgrade US debt. The media will focus on what Geithner did or didn’t say during his meetings with S&P in March and April. Nobody will ask about the ridiculous excuses S&P has made for the downgrades, or the fact that they are trying to wreck the American economy just as they did the British economy by playing God with their austerity prescriptions.

Back to the current post. Needless to say, since S&P has made a habit of using its clout to try to push around the US for its own profit as well as to advance an ideology, that of fetishizing “balanced budgets” and “debt reduction” in order to implement austerity, it should come as no surprise to see them take a similar approach abroad.

By Felipe Rezende, Hobart and William Smith Colleges. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives

S&P has issued a negative outlook regarding Brazilian sovereign debt. The S&P’s announcement stated that “Over the coming year, failure to advance with (on- and off-budget) fiscal and other policy adjustments could result in a greater-than-expected erosion of Brazil’s financial profile and further erosion of confidence and growth prospects, which could lead to a downgrade. The ratings could stabilize if Brazil’s political certainties and conditions for consistent policy execution–across branches of government to staunch fiscal deterioration–improved. It is our view that these improvements would support a quicker turnaround and could help Brazil exit from the current recession, facilitating improved fiscal out-turn and provide more room to maneuver in the face of economic shocks consistent with a low-investment-grade rating.”

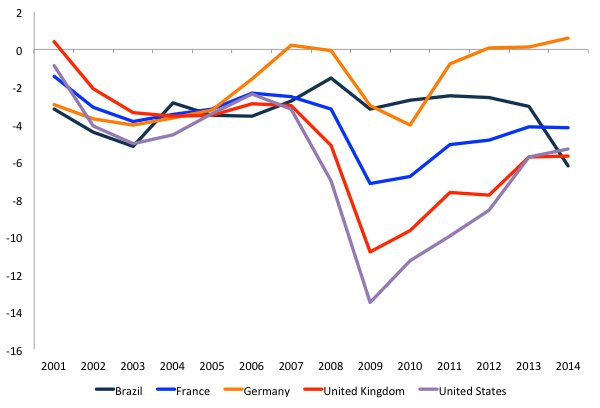

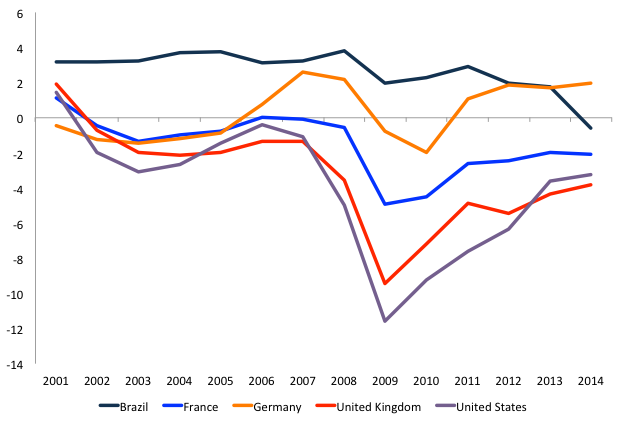

This warning has been echoed by other credit rating agencies threatening to downgrade Brazilian sovereign debt to junk. But, should anyone trust credit rating agencies? Once more, credit rating agencies are clueless in their assessments. They have specialized in making wrong assessments regarding sovereign government’s capacity to pay its local-currency debt. They have downgraded sovereign governments like the US, UK, Japan, and now Brazil. Paradoxically, credit rating agencies, which have a track record ranging from arbitrary, imprecise, and clueless (Here, Here , here, here) still can dictate the outcomes of fiscal policy of sovereign governments.

Recent downgrade warnings by CRAs and market pundits have triggered discussions inside the Brazilian government to implement austerity measures, including welfare programmes and public investment initiatives.

President Dilma Rousseff won’t change course. She has reiterated that ““[It] will last as long as necessary to rebalance our economy” President Dilma Rousseff She has invoked the government-household analogy stating that: “You who are a housewife or the father of a family know what this is…Sometimes we have to rein in expenses to keep our budget from going out of control…to ensure our future.” President Dilma Rousseff is under pressure to impose a fiscal-austerity agenda to avoid a downgrade by credit agencies.

The current direction of Rousseff’s policies has exposed its contradictory tendencies in combining austerity policies while trying to maintain or reclaim the pre-crisis progress. This combination leads to incoherent policy formulations and more drift rather than embracing a demand led strategy. The combination of austerity policies and the changed external conditions that prevailed during the bubble phase, such as increasing global demand for emerging market exports and rising financial flows to emerging markets, and the unlikelihood that the changed external conditions will ever revert back to the favorable conditions of the pre-crisis era creates a perfect storm for Brazilian economic policy. With Brazil’s investment grade credit rating at risk and the belief that bond vigilantes will pull the plug on bond prices and demand higher yields precipitating a fiscal crisis, Rousseff’s administration turned to fiscal austerity in a depressed economy. Thus, a progressive domestic development strategy is no longer on the agenda. Instead, the federal government is concerned with reducing its budget deficit by pursuing primary fiscal surplus targets, which excludes debt-servicing costs.

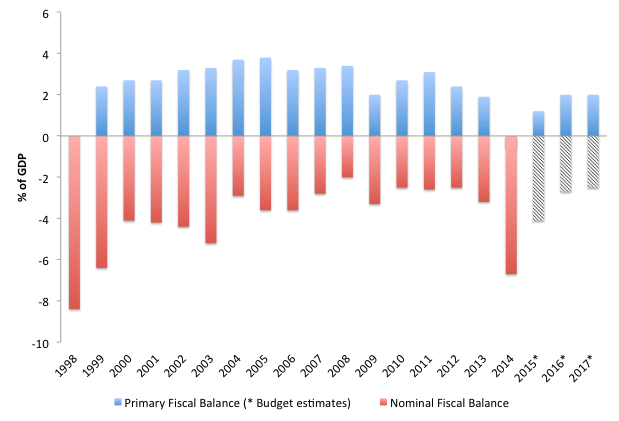

However, virtually all of its nominal deficits are due to interest payments, though debt service is a policy variable in which the central bank has a great deal of discretion over its setting of the benchmark Selic rate target, active manipulations of the interest rate target has been used to presumably achieve price stability.

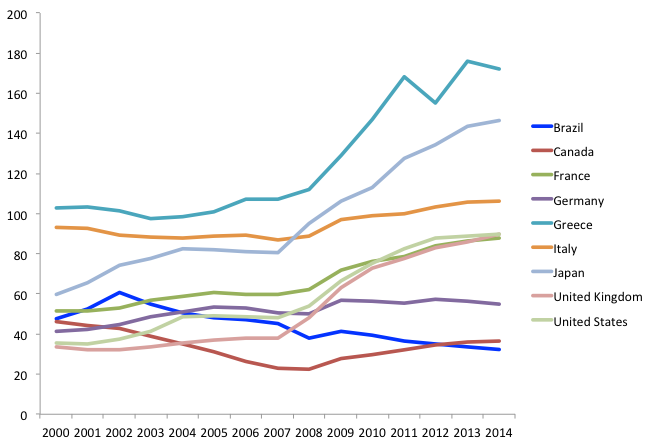

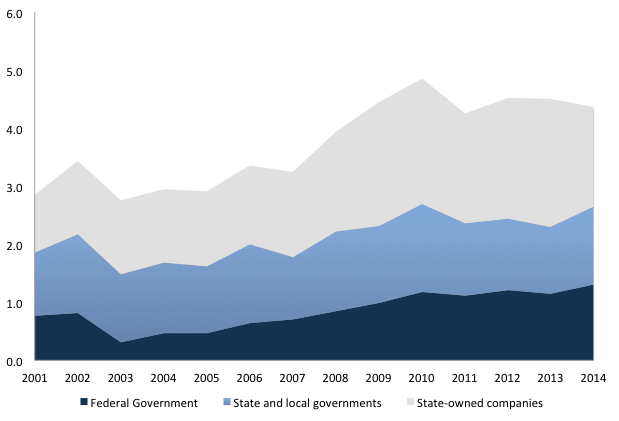

One of the CRAs concerns is related to gross debt, which increased to 65 percent of GDP in 2014. Because the government holds a portion of its own debt, the rise in the stock of outstanding government debt is mainly due to Treasury loans and infusions of capital in public banks and in particular to the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES) and its accumulation of international reserves (Rezende 2015). In this regard, net debt has been on a declining trend.

In spite of the well-known collapse of the theoretical arguments that a fiscal contraction is expansionary and the irrelevance of bond vigilantes, Brazil faces the emergence of a consensus in favor of fiscal austerity. Finance Minister Joaquim Levy’s attempt to impose old neoliberal austerity economic policies in the economic programs of the current administration deeply affected the direction of President Rousseff’s policy proposals, which exposed its contradictions of pursuing a development strategy within a conservative framing. To be sure, the government made a series of strategic mistakes for communicating, implementing, and enhancing fiscal policy. For instance, it failed to introduce a widespread tax cut and subsidies policy that would benefit all taxpayers and not just a few selected industries. Much of the policy debate took place within the wrong paradigm oscillating between “deficit hawks” and “deficit doves”. Framing the debate within the conservative space gives progressives no chance. They need to adopt an alternative approach based on modern monetary theory in which money is “part of an institutionalized practice designed to further the interests of the community—maintaining peace and justice” (Wray 2012: 6).

Contrary to President Rousseff’s claim, sovereign governments are not like households. As I have argued elsewhere, the federal government is the monopoly issuer of the currency. It cannot default on its domestic debt denominated in local currency. It must spend first to inject its currency into the system. The federal government cannot run out of money to pay its obligations denominated in local currency as they fall due. The Treasury account with the Brazilian central bank (BCB) is an accounting record of credits and debits to the Treasury. It spends by crediting banks accounts with the central bank and collects taxes by debiting bank accounts with the BCB.

Amid corruption scandals and pressures to run primary surplus balance, which excludes budgetary interest payments, the government curtailed the already timid public investment projects.

In Krugman’s words “the austerity drive isn’t really about fiscal responsibility, the push for “structural reform” isn’t really about growth; in both cases, it’s mainly about dismantling the welfare state.”