By Scott Fullwiler, Associate Professor of Economics and James A. Leach Chair in Banking and Monetary Economics at Wartburg College. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives

As anyone who’s followed the discussion has seen, the proposal from the newly-elected leader of the British Labor Party, Jeremy Corbyn, to implement “People’s Quantitative Easing” or PQE, has created a lot of controversy (Richard Murphy’s blog is a good place to see the PQE defense against these arguments). The basics of the proposal are that the government would create a public bank for financing infrastructure (National Investment Bank, or NIB), which the Bank of England (BoE) would then lend to directly in order to fund. The NIB would then carry out infrastructure projects to jumpstart the economy, create public capital, and create jobs.

The proposal obviously counters the austerity mantras going around in British politics (not to mention most other places), though Corbyn himself has paid lip service to balancing the budget, as well. The controversy, beyond the typical concerns with greater government spending of austerians, are fairly predictable for anyone who has taken a standard macroeconomics course (usually with a textbook written by someone who didn’t see the financial crisis coming)—

- first, the often heard QE = “printing money” = massive inflation argument is pervasive here with regard to PQE, as well;

- second, there are substantial concerns being voiced that “forcing” the BoE to finance the NIB will undermine the “independence” of the central bank and monetary policy;

- third, PQE gives the government free reign to spend by eliminating the need to fund its deficits in the financial markets.

So, here I want to look at the accounting and some basic operational realities of this proposal in order to understand how PQE does or does not do what the naysayers say it will.

For PQE, consider a NIB that is essentially an arm of the government carrying out its spending, so we can include it as part of the government simply spending from the government’s account at the central bank, while its purchases of infrastructure show up as government assets.

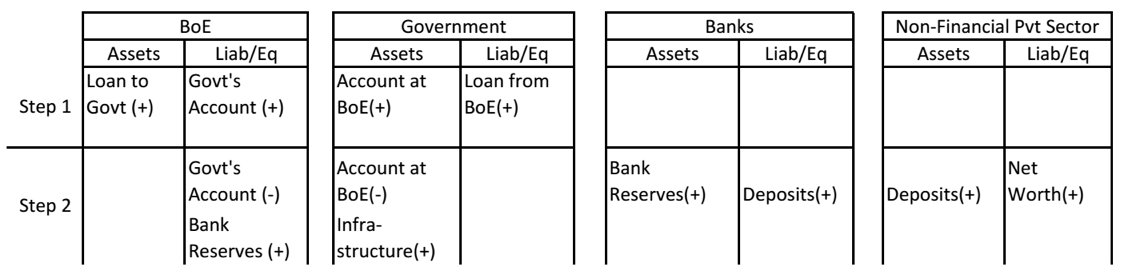

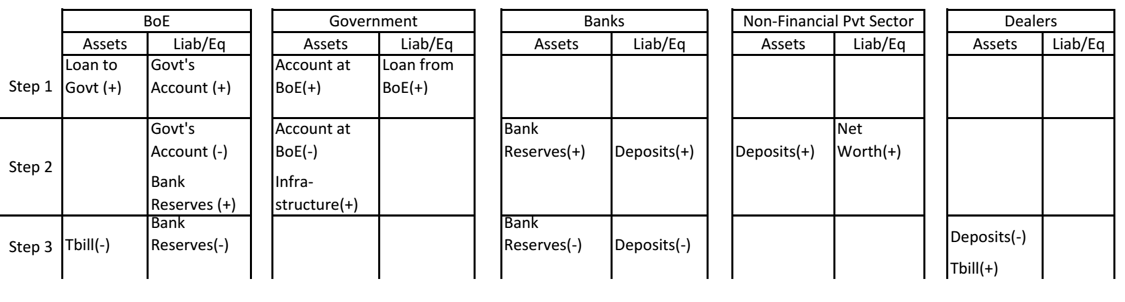

Here’s what it looks like if (Step 1) the BoE gives the government an overdraft, and (Step 2) the government spends (I’ll show below that there’s more to it than this, operationally, but just bear with me for now):

In Step 1, the loan from the BoE to the government shows up on both the government’s and the BoE’s balance sheets (obviously). In Step 2, the spending on infrastructure creates reserve balances, injected into the spending recipient’s bank’s reserve account, and a deposit is credited by the bank to the recipient that also raises the recipient’s net worth. (Of course, if the government is purchasing infrastructure, the spending won’t directly raise net worth of the builder itself, but when all is said and done, as a matter of double-entry accounting, the non-government sector’s financial net worth will have increased by the same amount as the government’s deficit increase as a result of the spending (e.g., wage income of employees of the builder, profits of the builder’s suppliers, and so on).)

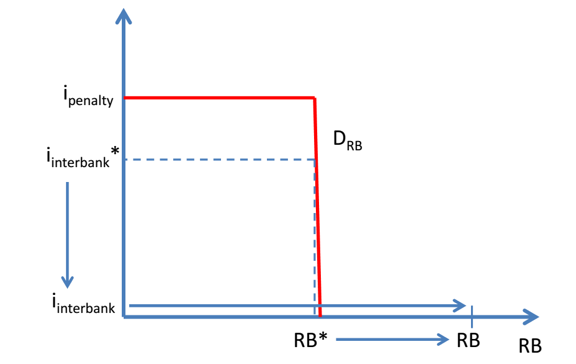

Note, though, that in Step 2, the BoE has created reserve balances that are also assets for banks. In the UK, reserve requirements are 0, so the demand for reserve balances will be very low and also highly inelastic (it’s not much different where reserve requirements are greater than zero, but it is a little different). Thus, if PQE is of any size of macroeconomic significance, it will shift the quantity of reserve balances beyond the demand as in Figure 1 and thus push the interbank rate to zero or near zero. In other words, left on its own, PQE creates a zero overnight rate, or ZIRP (Zero Interest Rate Policy).

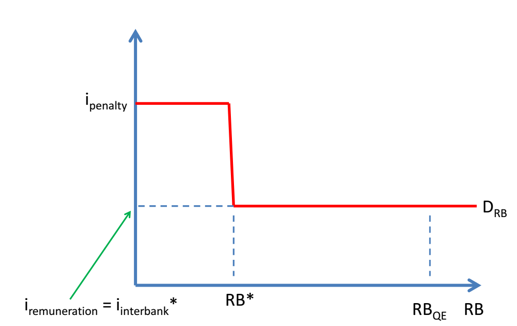

To avoid ZIRP and set a positive interest rate target, the BoE could pay interest on reserve balances (IOR) and set its interest rate target effectively equal to IOR, as shown in Figure 2.

This is a basic point of QE, and now PQE, that I have yet to see neoclassical economists acknowledge. It cannot be any other way. Think of any market if you’re not familiar with interbank markets—now, shift the supply curve so far that it is now completely to the right of the entire demand curve. What happens? The price falls to zero, unless you put in a price floor. This is Economics 101. With QE you get ZIRP or IOR = the target rate if you don’t like ZIRP and want the target rate above zero.

This is very significant. As I explained in more detail here, neoclassicals argue that paying IOR at the target rate stops QE from being inflationary, since in their view banks have the opportunity to earn IOR rather than make loans. They also argue that ZIRP stops QE from being inflationary, such as with Krugman’s version of the liquidity trap where “base money” (i.e., reserve balances) and Tbills both earn 0% and thus become perfect substitutes and more “money” is essentially the same thing as more Tbills (which isn’t the same thing as Keynes’s liquidity trap, but that’s a whole separate story).

From Figures 1 and 2, though, IOR = target rate or ZIRP are the ONLY TWO POSSIBLE OUTCOMES OF RISING RESERVE BALANCES AS A RESULT OF QE. Logically, then, neoclassicals own views on QE must conclude that the increase in reserve balances from QE is not inflationary.

So, continuing with the logic of the neoclassical argument, an increase in excess reserve balances that results from PQE must be accompanied by ZIRP or IOR = target rate, and from their own positions on the latter the rise in reserve balances themselves CANNOT BE INFLATIONARY. So, the first of the key arguments against PQE being made by neoclassicals and heard often in the financial press—that PQE will be inflationary because it raises the “money supply”—is inconsistent with the views held by these very same people.

Now, PQE could be inflationary if the additional spending on infrastructure pushes the economy beyond full employment, or creates bottlenecks in some key resource markets. Or, from the neoclassical perspective, ZIRP or even interest rate target = IOR could be inflationary if it results in the interbank rate being less than what they view is consistent with the natural rate of interest. Regardless, from the perspective of the neoclassicals own model the increase in reserve balances that PQE creates is not in and of itself inflationary.

In other words, from a basic consideration of accounting and simple supply and demand in the interbank market, the first objection to PQE—that it is inherently inflationary—is incorrect.

(This isn’t a topic for this post, but from the endogenous money perspective that I hold along with other MMTers, Post Keynesians, and an increasing number of authors in central bank research departments, both arguments by neoclassicals (IOR= target rate and ZIRP stop the rise in reserve balances from QE from being inflationary) are wrong.)

Let’s now consider central bank independence and PQE. What does “independence” mean here? I’m going to define it as (1) the central bank’s ability to set the interest rate target where it chooses as a result of its own ability to consult its preferred strategic response to the state of the economy (such as Taylor’s Rule), (2) its ability to manage the quantity of reserve balances circulating as it sees fit, (3) its ability to carry out non-traditional monetary operations (e.g., purchases of longer-term Treasuries or mortgages) in order to manage longer-term interest rates as it sees fit.

Now, as an aside, those that understand central bank operations—as detailed in the literatures on endogenous money and numerous publications by central banks—will know that there are cases in which even the most independent central bank can do (1) but not (2) or (3), such as in the pre-2008 method of central bank operations. But this is the central bank’s own choice of how to carry out its operations. It is now well known that setting IOR = target rate is operationally required for (2) to work (if it desires an excess supply of reserve balances and a target rate above zero). Thus, to simultaneously carry out (1), (2), and (3) as the Fed has done since late 2008, the operational requirement is IOR = target rate. However, even with IOR < target rate—as many central banks normally practice—it is possible to carry out (1) and (3) simultaneously as the operations for (3) would have to be sterilized with offsetting operations as in the US during early to mid-2008 or during Operation Twist.

At any rate, to sum up, under traditional, pre-2008 operations (1) and (3) are possible (assuming (3) is sterilized). If IOR = target rate, then all three are possible. The question is how or whether PQE changes this.

From Figure 2 above, clearly the BoE could set IOR = target rate and thus be able to still carry out (1), (2), and (3). For (1), it can simply adjust IOR up or down in order to move the target rate, since IOR = target rate. For (2), it can target any quantity of reserve balances along the flat portion of the demand curve (if it supplies less than as in normal times it will have to accept a rising interbank rate as given by the demand curve—discussed below). For (3), like the Fed now with IOR = target rate, it can carry out non-traditional operations to reduce longer term interest rates. All of this is possible as long as IOR = target rate, with or without PQE.

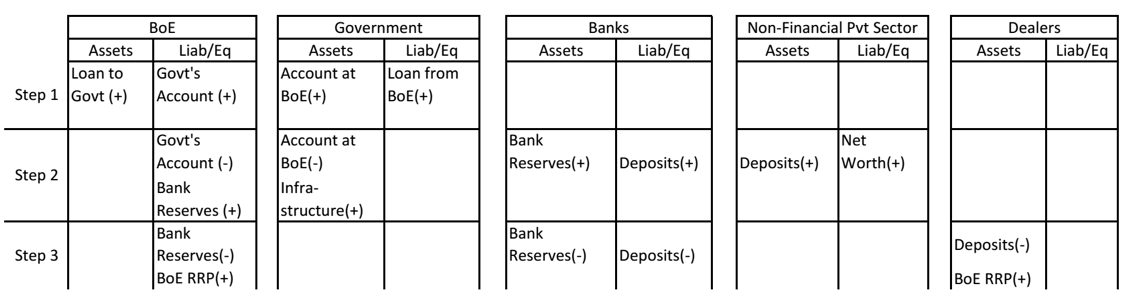

But what about the scenario in which the BoE wants fewer reserve balances to circulate than PQE has created? As Table 1 shows, PQE creates reserve balances, but the BoE might want a smaller balance sheet than PQE effects. In (2) above, the BoE can create more balances if it wants as long as IOR = target rate, but what about if it wants fewer balances circulating?

Consider Table 2, in which now there is a Step 3 showing the BoE carrying out reverse repurchase agreements (RRPs) to non-banks such as dealers as the Fed is now doing. RRPs can drain the reserve balances—all or just some portion, as desired by the BoE—that have been created by PQE. Indeed, if the BoE wants to return to the pre-2008 method of operations, it can actively use RRPs to set its balance sheet size comparable to that period (allowing for growth in the demand for currency since then, of course) provided it is willing to raise the rate it offers on RRPs to coincide with the more inelastic portion of the demand for reserve balances as the quantity circulating is reduced. Just as easily, the BoE could instead allow banks to trade in their reserve balances created by PQE for time deposits instead of RRPs as many other central banks have done for years.

Another essentially equivalent option for the BoE would be to sell assets off of its balance sheet. Table 3 shows, for example, the BoE selling Tbills to dealers in Step 3 instead of RRPs.

There is one additional aspect of central bank independence that I have left out that could be potentially affected by PQE. Note that as a result of PQE the BoE will have to either pay IOR on the additional reserve balances created or pay interest on its RRPs or time deposits to drain them—in other words, there is no such thing as PQE creating “money” unaccompanied by ZIRP, IOR = target rate, or the BoE draining the reserve balances via RRP or something similar.

The payment of IOR reduces the BoE’s profits, and potentially its equity if the BoE ends up with negative profits, which could have political repercussions even though it shouldn’t (as the monopoly creator of reserve balances, the BoE can never be “bankrupt,” though politicians don’t always allow for this reality). In this case, what should happen is that the BoE be allowed to charge at least about as much interest on the loan it provides to the Treasury as it pays on its reserve balances, RRPs, or time deposits. This has no effect on the government’s budget if—as is common practice—the central bank returns its profits to the government, but can eliminate political concerns with the BoE’s equity position that might affect its independence.

So, aside from the matter of charging interest on the loan from the BoE to the government to avoid a fall in the BoE’s equity, the second objection to PQE is also incorrect.

Now, for the third objection, the question is whether PQE is reducing or even eliminating the ability of markets or even central banks to provide “oversight” over the actions of the government. I’ll leave aside the counter argument here that it is at the very least questionable whether we want markets or central banks to do that in the first place since I am only addressing the objections to PQE in this post. As Bill Mitchell explained, this is quite different from QE as central banks have been doing it the past several years. Traditional QE is not actually a helicopter drop. Rather, helicopter drops are fiscal operations, since government deficits raise the net worth of the non-government sector. Traditional QE is an asset swap that, like all other monetary policy operations, does not alter the net worth of the private sector.

As Bill explains, though, because PQE involves government deficit spending, PQE is in fact, as Stephanie Kelton termed it, Overt Monetary Financing of Government (OMFG). Some refer to this as “public control of the money supply,” but that’s not really true (depending on how one defines the “money supply”) as the BoE can still control the quantity of reserve balances outstanding as discussed above and shown in Tables 2 and 3. On the other hand, if the BoE does this, it nonetheless doesn’t stop the fact that with PQE the government has spent without having to go to markets or the central bank itself.

But does this matter in the sense of being much different from “plain vanilla deficits” (PVD) the government might run in the absence of PQE?

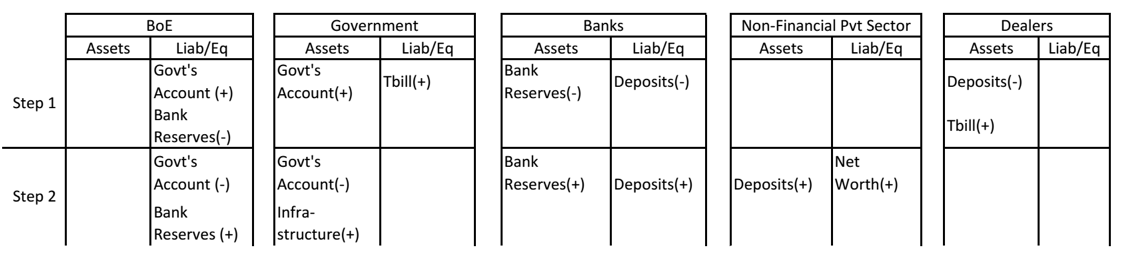

Instead of PQE, Table 4 shows a standard PVD run by the government to finance infrastructure spending. In this case, the government will issue Tbills to replenish its account at the central bank before it undertakes the infrastructure spending. In Step 1, the government sells a Tbill to a bond dealer. In Step 2, there is spending on infrastructure.

(Of course, from the MMT perspective, there is nothing “plain vanilla” about this, since it is the government that is requiring itself to sell the Tbills before it spends. This is nothing more than a self-imposed constraint—OMFG would be more in line with “plain vanilla” if this were better understood. A currency-issuing government never needs to finance its spending in financial markets, and as discussed above OMFGs like PQE do not raise additional risks of inflation. Nonetheless, this post is written to address critics of PQE, so I will stick with the more common definitions.)

There are two important things to understand from Table 4 relative to the previous tables. First, all four tables show that PQE or PVDs raises the net worth of the non-financial private sector. From the neoclassical perspective, none of these scenarios are more inflationary than any other assuming the central bank’s target rate is the same in all four—there is IOR = target rate in Table 1 and sterilization of the spending in Tables 2, 3, and 4 via Tbill sales or RRPs. The impact in all four on aggregate demand is thus simply the infrastructure spending itself.

Second, for a currency-issuing government like the UK’s operating under flexible exchange rates, the debt service in all four scenarios is essentially the same. In Table 4, the debt service on PVD is the Tbill rate, which will arbitrage quite closely with the BoE’s target rate. In Table 1, the government’s debt service is a bit more complicated—recall that in most cases central banks transfer their profits to the national government. This means that paying IOR = target rate on the OMFG that results from PQE (are you keeping up with all the acronyms?) reduces the BoE’s profits returned to the government by the total IOR paid on the OMFG. But this reduction in profits sent to the government in Table 1 will be about the same as the amount of debt service paid by the government in Table 4, so the effect on the government’s budget from debt service (either by the government or by the BoE on IOR) either way is essentially the same.

In Tables 2 and 3, the effect is basically the same again—in Table 2, the RRPs earn a money market rate similar to the BoE’s target rate, while in Table 3 the Tbill now circulating is just like the Tbill issued in Table 4.

So, the fact that the government has to issue Tbills in financial markets in the case of PVD is not materially different from OMFG in PQE, because it is not operationally possible to do OMFG without IOR = target rate, RRPs at roughly the target rate, or sterilizing OMFG by selling financial assets like Tbills held by the BoE. The government’s Tbill rate will arbitrage with these rates since it is just as risk-free to the private sector as is the central bank’s liability earning IOR = target rate (note that the central bank is a legal agency for sovereign currency issuing governments, so the government’s debt can’t be any more risky than one of its agencies’). The BoE’s interest rate policy effectively sets the interest rate on the national debt; it doesn’t control whether or not the government can issue the debt and it does not decide whether or not or how much overall the government can spend. And this is all true whether or not there is PQE, OMFG, or PVD.

The issuance of Tbills in PVD doesn’t “crowd out” financing in financial markets. Yes, there is a dealer that has spent a deposit to purchase the Tbill in Table 3, but dealers are backstopped in repo markets by the BoE and also by banks (themselves backstopped by the BoE). So, the funds for purchasing Tbills is created out of thin air at the margin, not prior savings. All of this is not even to mention that the reserve balances required by the banking system to settle the dealers’ purchases of Tbills with the government are created by a sale of previously issued government debt (either outright or in a repo) from the BoE. In short, those that argue that PVD somehow constrains the government or the financial system overall more than OMFG does are wrong.

So, in the end, all three arguments against PQE are incorrect.

- Is PQE inherently inflationary? PQE is only as inflationary as the spending itself.

- Does PQE limit central bank “independence? The BoE’s ability to set rates is not affected, and if it sets IOR = target rate, it can target the quantity of reserve balances and/or carry out non-traditional operations like QE, etc., just as without PQE.

- Does PQE encourage profligate government spending? A monetarily sovereign government spends and taxes as it chooses through the political process (i.e., Parliament/Congress, Prime Minister/President) laid out in the nation’s laws, and this is so whether it deficit spends via PVDs or OMFGs via PQE. The central bank for such a government sets an interest rate policy that effectively determines the interest rate on the national debt; again, this is so whether government deficits are of the PVD or OMFG variety.

In other words, PQE via OMFG changes very little, if anything, operationally. That is, PQE is not significantly different from PVD once we consider accounting and operational realities. The key is thus not that PQE or OMFG creates “money” directly relative to PVD, but that PVD, PQE, and OMFG all directly create spending and net worth for the private sector—this is what fiscal policy in any of these forms brings to macroeconomic policy that monetary policy alone via interest rate changes or QE operations cannot.

While PQE does not change the nature of fiscal policy, it does change the framing of the debate about fiscal policy, or attempts to do so, to show that the government doesn’t have to finance itself, ever. If it works, it would be a tremendous improvement on the more standard discussions we see regarding fiscal policy. Unfortunately, the economics establishment’s understanding of monetary operations is so poor that we are inundated by objections to PQE based on the more standard framing shown here to be incorrect

There are two final things worth pointing out regarding the MMT view on PQE. First, MMTer Randy Wray wrote a paper in 2001 calling for essentially a PQE-like program in the US. Second, Warren Mosler has noted that simply having the government guarantee debt issued by the NIB would perhaps be a more politically palatable solution that would be essentially identical—the national government would decide how much the NIB could borrow/spend and the NIB would then be able to borrow at effectively the same rate the government issues its debt, itself based on the central bank’s target rate. As such, government guaranteed debt of the NIB would be effectively the same thing as PVD, which as shown above is not different in a macroeconomically significant way from OMFG via PQE.

What I don’t quite understand: What is the advantage of PQE over a traditional development bank (i.e. what Brazil, China, Germany, and some other countries are doing)? The only difference I’m seeing is that PQE does money creation directly, while a development bank borrows money at government rates. And I’m not sure why this is a plus?

Conversely, PQE has the disadvantage that its effects seem to still be somewhat speculative, while development banks are fairly well understood.

It’s good Dr. Fullwiler makes clear the necessity of paying a maintenance rate in an arrangement where the central bank directly finances government expenditures; so long as the central bank is required to set an interest rate it will need to set a floor through which those rates cannot fall. Doing differently will require changes to the Federal Reserve Act.

Excuse me, changes to the Bank of England’s charter, not the Federal Reserve Act.

The point is how credit actually functions, not what flexible laws are laid over the top. That’s the whole point. Money is always created as credit on a balance sheet somewhere and is ALWAYS subject to the fundamental laws of the balance sheet. Yes, all sorts of ‘national’ mechanisms can be overlaid on top, but you CANNOT escape what is fundamentally happening on the balance sheet. Your comment reveals that you don’t understand balance sheets and until you do, you will never fully understand the system or be able to make useful informed comments.

You don’t know what a maintenance rate is, do you?

I’m afraid there are some serious mistakes in this article. There are plenty of bold assertions, but little in the way of evidence as to why PQE will have no negative consequences. It also plays to the typical MMT arguments – limited to cases where it could work and the model deliberately ignores externalities.

“As I explained in more detail here, neoclassicals argue that paying IOR at the target rate stops QE from being inflationary, since in their view banks have the opportunity to earn IOR rather than make loans.”

I’ve never seen this said. QE is designed to lower yields and make loans more attractive. Low rates then supporting growth are the driver of any increase in inflation. QE does not greatly affect the money supply (M0 barely affected).

“that PQE will be inflationary because it raises the “money supply”—is inconsistent with the views held by these very same people.”

Except this is exactly what PQE aims to do. It is overt monetary financing, unlike QE which is in truth an asset swap. PQE directly increases M0 money supply by printing it. Rehypothecation then dramatically increases a smaller M0 injection. Thanks to the ECB we know that M3 has a fairly good link to inflation, and this is exactly what the FED are worried about at the moment as we go into this week’s meeting.

You also make the mistake when talking about rising reserves forcing a ZIRP. That would work in a closed system, but we know full well that the UK economy is not a closed system. Those bank reserves will flow out of GBP and into a variety of other assets – likely to be non-GBP denominated or hard assets, again driving inflation higher and the currency weaker.

As for central bank independence:

If the government resorts to simply printing money – and lets call it that, given that is exactly what it is – the target rate becomes less important and less effective. With the government in control of money supply, the BOE can try and tame inflation with base rates, but the yield curve is market determined. More importantly, and attempt to control the money supply through controlling reserve balances would entail the BOE soaking up that cash through the sale of debt instruments. Which takes us back to square one, and makes PQE equivalent too standard debt issued financing, and therefore pointless.

There would also be the risk that the BOE simply cannot soak up enough liquidity through debt issuance, through lack of demand or the cost being too high for government to bear. This is a massive failure of MMT, which simply assumes that excess liquidity can be contained by removing reserves through sale of debt and higher taxes. In reality, there is an event horizon to this where tax hikes simply have little or no effect (given taxes simply cannot be over 100%) and bond sales also fail to contain the ever expanding money supply.

Note also that the real differentiator between PQE and QE is that PQE “cancels” debt. The BOE has no assets to sell to remove reserves. Instead new bonds need to be sold and excess reserves destroyed in a reverse of the PQE process.

Which renders the third point you make rather moot. The oversight of government you talk about is essentially the BOE’s ability to control the money supply – which has now been hampered if not destroyed. That too is before government’s records of poor fiscal rectitude.

Two questions then follow:

1. If PQE, or more generally printing money or OMFG is so easy, cost free and non-inflationary, why has it not been tried before? Or it if has, has it ever been successful?

2. With all the apparent drawbacks and risks to PQE/OMFG, and with interest rates currently so low, why is PQE/OMFG even need when, as you say, PVD or standard debt issuance is not crowing out markets.

Of course, back in the real world we know that PQE/OMFG has been tried before, repeatedly, with disastrous results. Economic damage and outright failure to put it lightly. Venezuala are trying it at the moment. The result? The currency is crashing and inflation is over 100% annually (though probably higher given they refuse to publish it any more).

Setting aside the fact that, as MMT shows, a government with a sovereign currency always has more money at its disposal, the constraint as a result of funding through financial markets argument always struck me as wrongheaded, because, simply, it’s never been much of a deterrent historically. During the Cold War the USG always deficit spent as much as it wanted to, with little or no care for how much “debt” was being taken on. The financial markets were always willing to lend more. And you see this play out with municipalities as well, where the funding actually does have to come from somewhere. Wall Street was always willing to lend more and more, even in circumstances where the decision to do so seemed completely ridiculous.

I’m open to being convinced, but I don’t really see any examples of time when financial markets actually imposed a constraint on governments, at least not in recent memory.

Greece?

Greece has a sovereign currency?

Ok. Russia. Ukraine. Venezuala. Argentina.

Russian State constrained by markets? Not convinced that happened so can’t comment.

Ukraine, Venezuela and Argentina all borrowed foreign currency, so, yeah they got handcuffed by financial markets. Zimbabwe same. Weimar Republic same. This argument is tired. Debt in foreign currency ≠ sovereignty.

What a nation can afford is only constrained by its natural resources and human capital, unless it cedes its sovereignty to a foreign currency or central bank.

All borrowed someone else’s currency.

MMT acknowledges that taxes give value to money but I think they sometimes underestimate the importance of taxes in developing a workable and well-functioning sovereign space.

Political economy is, first and foremost, political. MMT assumes a certain degree of capacity to compel order (be it rule of law or otherwise) and control over basic economic functions. In places where order breaks down (Tyler’s quad above is a good example), the vultures come from without with their own money and own values attached.

“MMT acknowledges that taxes give value to money”

MMT acknowledges that taxes force those under the currency issuers jurisdiction to use the currency…if one earns income subject to taxation, one must acquire the currency of issue to satisfy their tax liability. Beyond that taxes serve as a means to control demand, and thus inflation.

“[MMT] sometimes underestimate the importance of taxes in developing a workable and well-functioning sovereign space.”

You haven’t read any MMT literature have you? Define a workable and well-functioning sovereign space.

I like MMT but think they could benefit from incorporating more Ingham.

I think Argentina presents a cautionary example as the inability to establish a ‘money of account’ to measure value led them to an array of currencies, local IOUs, vouchers and other informal monetary arrangements.

This seemed to produce this result:

‘Money generated by Argentine capitalism has customarily sought to become dollars and to find itself safely deposited in New York and London.’ (Ingham)

It seems to be important to establish a reliable ‘money of account’ in a domestic space for the currency to have value that can be trusted by all segments of the population. If this is established it can help contain capital flows and make them more self sufficient and help keep them off the dangerous foreign dole.

As MMT points out this value comes from being able to reliably tax the population. It’s how the state convinces the private players that the money has value and can stay at home.

Though MMTers are quick to criticise other economic theories, there a plenty of problems with MMT itself.

One big problem is that it really only works in a closed system. By removing externalities you can get the theory to work. Once those real world externalities are re-introduced the whole thing comes crashing down.

For example, it’s a common argument that a government cannot default if it issues it’s own currency and it’s debt is denominated in it. Technically this is true. In practical terms it is totally false.

If you buy bonds in a company and it defaults (explicit default) you will lose some or all of your money, depending on the recovery value. Even Lehmans had about a 20% recovery rate.

If you buy government bonds denominated in the local currency, you will normally get your face value investment back. That does NOT mean you haven’t lost money though. Inflation and purchasing power parity could have cost you just as much as a defaulted Lehmans bond. If that government is printing money to repay debt, you can almost guarantee it. Those loses, if severe enough, are essentially seen as an implicit default.

Which is where the MMT closed system error comes in. The author says that an over-supply of reserves will lead to ZIRP. SO is using supply and demand to suggest an oversupply of something will lead to it having a lower price. But then he also says that this same oversupply of something – in this case money supply – will NOT cause inflation. You can’t have it both ways.

Nor is the system a closed system. If a bank has too many reserves, and is likely to get zero for them if placed at the central bank it is likely to try and place them somewhere else to get a better return. MMT assumes that the banks can’t do this – as otherwise the MMT control of the money supply totally breaks down.

Back in the real world there is nothing to stop a bank, especially one fearful of a weakening currency and inflation, to use those reserves. Maybe by lending them out (increasing money supply still further), by buying assets/property (inflation hedge, increasing demand, pushing asset inflation higher) or simply converting those reserves into a different currency and getting more for that currency when placed on deposit (weakening the currency and again driving inflation higher through PPP).

It’s a massive flaw in MMT and therefore PQE.

the gaping hole in your real world argument is you don’t understand how the real world works.

1. Bank reserves are assets. The bank will not be willy nilly loaning out its cash assets and diluting its reserve ratio.

2. The bank is not going to get a risk free rate better than the central bank. It will have to purchase riskier assets from another financial entity, who will then park the cash in their own reserve account.

3. Ignorant people have been wetting their pants over inflation since GFC day 0. ZIRP has been around for years, either they don’t fear inflation or the money does a merry go round and ends up back in reserves.

4. If the bank buys foreign currency, it sells domestic currency to the seller, who promptly parks it back in reserves again.

You seem to think that the money somehow leaves the banking system….wrong!

Hint…. MMT is not an “Economic System”…

MMT does recognize externalities such as resource constraints and foreign exchange but it might help if they emphasized these more.

The main point Scott is making is just to re-examine what is possible and a more correct way to look at it. MMT policy has always recommended responsible spending rather than just printing money for its own sake which would run into these resource and foreign exchange constraints.

http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2014/02/mmt-external-constraints.html

MMT AND EXTERNAL CONSTRAINTS

February 24, 2014

By L. Randall Wray

“I have no doubt that China would eventually be in a position where floating (her currency) would not only be desired, but it would be necessary.China will probably float long before it reaches such a position. China will become too wealthy, too developed, to avoid floating. She will stop net accumulating foreign currency reserves, and will probably begin to run current account deficits. She will gradually relax capital controls. She might never go full-bore Western-style “free market” but she will find it to her advantage to float in order to preserve domestic policy space.

If she did not, she could look forward to a quasi-colonial status, subordinate to the reserve currency issuer. China will not do that.”

“The financial markets were always willing to lend more.”

The financial markets are always and will always be willing to allow the ‘people’s money’ to pass through their toll gates, awarding themselves interest in perpetuity. It’s a money-for-nothing game.

I wouldn’t call this a loan, and to continue doing so only adds to the perception that these same financial institutions are necessary to conduct government business.

I was trying to be careful with how I contextualized my response, but apparently I missed the mark. The “always willing to lend and lend” was with regard to the municipal bond market, i.e. cities that actually do have to borrow money in real not just ideological terms. Of course, the banks lending to them are mostly doing it with the same money they get through QE, so maybe that’s what you meant? Anyhoo, I didn’t mean to imply that the USG actually takes out loans, just that even in their ideology of debt and deficits, there was never any real constraint on spending, only the will to do so.

Thanks – great analysis that answered most of my questions. Can I ask how the different methods of funding the NIB would be reflected in calculating the National Debt of the UK?

Although I obviously misunderstood your intent re this sentence, I was mostly just seizing an opportunity to push back against the pervasive ‘borrow’ meme, which I’m kind of anal about.

Apologies if it came across as criticism. Always good to see an MMT’er in comments.

Edit. This comment is in response to Uahsenaa @ September 15, 2015 at 9:31 am

Let’s be perceptive back in the 17th century the smart wealthy in England spotted the opportunity to make money by taking advantage of the need to contain inflation caused by the human instinct for aggression, England’s warring with France triggering the creation of the Bank of England and the subsequent pattern of government bond issues around the world. (“The Financial Revolution In England” by P.G.M. Dickinson published 1967)

So in terms of accounting: Can a country that fears inflation and thus allows itself to fall into disrepair be completely dilapidated and therefore depreciated, agree to be sold off to the bottom feeders who demanded unaffordable interest rates for deadbeat countries for pennies on the dollar? No, only in terms of even more draconian borrowing rates. Is this sane? Even the EU backs off this model.

There are so many loaded terms, “oh look there’s no inflation” um hello except for the massive inflation in every investment asset, seems to me People’s QE at least has a shot at helping actual people versus just gifting financial market parasites with a free COGS for their equally risk-free gambling (with the chump taxpayer always left holding the bag when they lose). Can’t help but wonder where we’d be if TARP’s original purpose (helping underwater mortgage holders) had been followed through instead of Paulsen’s bait and switch…truly one of the most brazen financial crimes in an era that will be remembered as the shining Golden Age of financial crime.

Not sure if Naked Capitalism will approve this post but I hope so, so here goes…

If you go to my webpage http://www.houghton.hk and scroll down to beneath the economics chapter, you’ll see a new page called “The Financiers and the Nation.” Its a frightful litany of City frauds for a century up to time of writing just before WWII. No need to read all that appalling stuff – just go to the end where there are remedies for overcoming the BoE or any other central bank and asserting real public control of the money.

I expect PQE comes from these attempts in 1930s to escape the moneymen’s tax.