Dave here. Well-articulated points, the book sounds like it could be a good primer for newbies.

By David Kotz, a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst and the author of The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism (Harvard University Press, 2015). This is the first installment of a two-part series based on his book. Cross-posted at Triple Crisis.

Part 1: What is Neoliberal Capitalism?

“Neoliberalism,” or more accurately neoliberal capitalism, is a form of capitalism in which market relations and market forces operate relatively freely and play the predominant role in the economy. That is, neoliberalism is not just a set of ideas, or an ideology, as it is typically interpreted by those analysts who doubt the relevance or importance of this concept for explaining contemporary capitalism. Under neoliberalism, non-market institutions – such as the state, trade unions, and corporate bureaucracies – play a limited role. By contrast, in “regulated capitalism” such as prevailed in the post-World War II decades – in the United States and other industrial capitalist economies – states, trade unions, and corporate bureaucracies played a major role in regulating economic activity, confining market forces to a lesser role.

A few clarifications are in order. First, capitalism cannot function without a state. After all, private property is a creation of the state, and market exchange requires contract law and associated enforcement that can only be provided by a state. However, in neoliberal capitalism the state economic role tends to be largely confined to protection of private property and enforcement of contracts. In regulated capitalism the state’s economic role expands significantly beyond those core functions of the capitalist state.

Second, the dominant role of market relations and market forces in neoliberal capitalism is embodied in a set of institutions and reinforced by particular dominant ideas. The transition from regulated capitalism to neoliberal capitalism starting in the 1970s was marked by major changes in economic and political institutions. This will be explored below.

Third, the institutions of neoliberal capitalism, while promoting an expanded role in the economy for market relations and market forces, simultaneously transform the form of the main class relations of capitalism. Most importantly, the capital-labor relation assumes the form of relatively full capitalist domination of labor. This contrasts with the capital-labor compromise that characterized the regulated capitalism of the post-World War II decades. Neoliberalism also brought change in the relation between financial and non-financial capital, as will be considered below.

Economic Developments in the Neoliberal Era

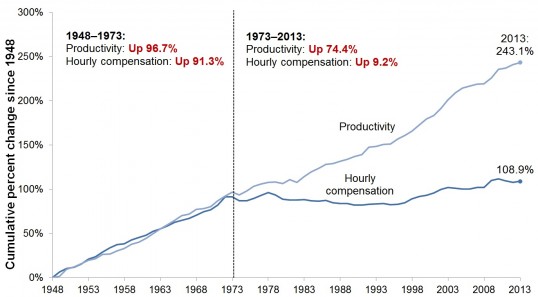

The most talked about economic development in the neoliberal era is rapidly rising inequality. While Thomas Piketty’s now-famous book, Capital in the 21st Century, documented the relentless rise of the income share of the top 1%, he did not provide a convincing explanation of that development. The neoliberal form of capitalism supplies a clear explanation. As neoliberal restructuring undermined labor’s bargaining power, the real wage stagnated while profits rose rapidly. Figure 1 shows the big gap after 1979 between the growth rate of profit and of wages and salaries (which include managerial salaries). That gap jumped sharply upward after 2000. Another feature of neoliberal capitalism, the development of a market in corporate CEOs, drove CEO pay in large corporations up from 29 times that of the average worker in 1978 to 352 times as great in 2007.

My new book The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism explains in detail how the institutions of neoliberal capitalism account for two other important economic developments since 1980. One was the transformation of the financial sector from a stodgy provider of traditional loans to businesses and households and the sale of conventional insurance into speculatively oriented companies that developed a series of highly risky so-called “financial innovations” such as sub-prime mortgage backed securities and credit default swaps. The most important cause of this change in the financial sector was its deregulation, a key part of neoliberal restructuring, starting with the first bank deregulation acts of 1980 and 1982 and culminating in the last such act in 2000. A contributing factor was the intensifying competition of neoliberal capitalism, which drove financial institutions to more aggressively seek the maximum possible profit, which for financial institutions always involves moving into speculative and risky activities.

Second, a series of large asset bubbles emerged, one in each decade. The 1980s saw a bubble in Southwestern commercial real estate, whose collapse sank a large part of the savings and loan industry. In the second half of the 1990s a giant stock market bubble arose. And in the 2000s a still larger bubble engulfed US real estate. The preceding period of regulated capitalism had no large asset bubbles. The rapidly rising flow of income into corporate profit and rich households exceeded the available productive investment opportunities, and some of that flow found its way into investment in assets, tending to start the asset price rising. The eagerness of the deregulated financial institutions to lend for speculative purposes enables incipient asset bubbles to grow larger and larger.

Neoliberalism and the Crisis of 2008

The three developments noted above – growing inequality, a speculative financial sector, and a series of large asset bubbles – account for the long, if not very vigorous, economic expansions in the US economy during 1982-90, 1991-2000, and 2001-07. The rising profits spurred economic expansion while the risk-seeking financial institutions found ways to lend money to hard-pressed families whose wages were stagnating or falling. The resulting debt-fueled consumer spending made long expansions possible despite declining wages and slow growth of government spending. The big asset bubbles provided the collateral enabling families to borrow to pay their bills.

However, this process brought trends that were unsustainable in the long-run. The debt of households doubled relative to household income from 1980 to 2007. Financial institutions, finding limitless profit opportunities in the wild financial markets of the period, borrowed heavily to pursue those opportunities. As a result, financial sector debt increased from 21% of GDP in 1980 to 117% of GDP in 2007. At the same time, financial institutions’ holdings of the new high-risk securities grew rapidly. In addition, excess productive capacity in the industrial sector gradually crept upward over the period from 1979 to 2007, as consumer demand increasingly lagged behind the full-capacity output level. All of these trends are documented in The Rise and Fall of Neoliberal Capitalism.

The above trends were sustainable only as long as a big asset bubble continued to inflate. However, every asset bubble eventually must burst. When the biggest one – the real estate bubble – started to deflate in 2007, the crash followed. As households lost the ability to borrow against their no longer inflating home values, consumer spending dropped at the beginning 2008, driving the economy into recession. Falling consumer demand meant more excess productive capacity, leading business to reduce its investment in plant and equipment. The deflating housing bubble also worsened investor expectations, further depressing investment. Finally, in the fall of 2008 the plummeting market value of the new financial securities, which had been dependent on real estate prices, suddenly drove the highly leveraged major commercial banks and investment banks into insolvency, bringing a financial meltdown.

Thus, the big financial and broader economic crisis that began in 2008 can be explained based on the way neoliberal capitalism has worked. The very same mechanisms produced by neoliberal capitalism that brought 25 years of long expansions were bound to eventually give rise to a big bang crisis.

I highly recommend Kotz’ “Russia’s Path from Gorbachev to Putin.” He shows how the collapse of the Soviet economy resulted from the failure by Soviet elites to mobilize its considerable industrial strengths within a “developmental state” model and instead to engage in looting, primarily natural resource-based. (Yes, the familiar short-term vs. long-term mindsets.) Contrary to MSM spew, the Soviet economy was still growing, albeit slowly, up to the point when central planning institutions were dissolved in the late 80s. A political agenda geared to a “Never Again” destruction of central planning capacities, a too rapid opening up of the Soviet economy to competition with Western multinationals and simple venality has set up an lop-sided natural resource dependent economy. His analysis is based on a collection of interviews with elite figures.

Thanks for that book tip. It looks interesting. I think post-Soviet Russia is an important thing to understand when looking at today’s politics.

By what criteria does this describe our contemporary system of political economy? Neoliberalism is the antithesis of capitalism. It does not believe in markets and rule of law and a limited role for bureaucracy. It believes in limited markets and a predominant role for the bureaucracy and a two-tiered justice system. I challenge the author to name an area of the American economy where non-market institutions play a limited role.

The unwillingness of our intellectual class generally, and academic economists in particular, to even describe, let alone confront, the totalitarian trajectory of public policy will be one of the most notable aspects historians describe when talking about our era.

Good point

Thanks, I’m excited this has sparked a whole variety of perspectives.

The “market” certainly no longer refers to competition as a dynamic in the production and distribution goods and services. Instead, it means something more along the lines of international financial monopolies protected by collusion between corporate captured local states, (including saturation of executive, legislative, judicial, penal and enforcement branches of government), educational institutions and media. I wonder if “trade deals” doesn’t better describe the phenomenon that has replaced “markets.”

Take a look at Michael Hudson’s new book, “Killing the Host”. This “unwillingness” becomes understandable once you realize the most (in)famous members of the intellectual class – and that particularly includes academic economists – are really nothing more than employees of the creditor class paid to administer intellectual anesthetic to debt peasants who still have enough time to ask what’s going wrong while they try to hold the Wolves of Wall Street at bay.

The behavior of the intellectual class down through the ages is what – with notable exceptions like Hudson, Veblen or Marx – gives intellectuals a bad reputation among the laboring cattle. Their message is always the same – “Whatever is is right.”

It’s the difference between “we should use markets to efficiently allocate resources” and “Capitalists should rule”.

A nation’s political system can be described by what types of power it legitimizes and delegitimizes, and whose power it protects. No matter what we tell ourselves about our supposed political system (“constitutional federalism”, “republican democracy”) and economic system (Free Market Capitalism), you can tell what we really have by looking at whose power the state protects. The Neoliberal project has sought quite successfully to delegitimize republican federalist state power and legitimize corporate and wealth power in its place.

If we really were in a capitalist system, the state would still actively intervene to make sure that markets actually allocate resources efficiently. That is to say, the state would break up monopolies and discourage rent extraction. If we really were in a representative democracy, our elected officials’ actions would hew more closely to the priorities that polls show the voters to have.

I’m curious what you mean by

I could see you going in a number of different directions, so I’m not sure whether I agree or disagree.

From what I see, neoliberals love state power. They almost can’t help themselves from using government to interfere with citizens’ lives. It is not a competition of wealth over the state. It is a merger of state bureaucracy and private bureaucracy, a public-private partnership.

Neoliberalism is not a post-war version of capitalism. It’s a post-war version of fascism.

I think you really hit the nail on the head here. It’s an important understanding to come to before one can understand how the violence and criminality of it all play a part rather than are some aberration.

Neoliberals do love state power, and have subordinated it to their purposes. What has been delegitimized are other groups or ideas to which state power has been subordinated in other times. Power does not reside in the hands of the people (thru the theoretical ability to drive out politicians who fail to adequately safeguard our welfare). Regulatory agencies have power, but not to benefit the interests of the people over the interests of the corporations they are supposed to regulate. The state does not act to ensure the efficient allocation of resources, but it does act to protect the interests of the Boardroom Class. It no longer acts to preserve checks and balances. Much of this came through promoting the notion that the government is an illegitimate market actor which is to blame for distorting markets (and that not distorting markets is more important than mere values, ideals, or institutions).

The general term for the type of totalitarianism you are describing is fascism.

Until that last sentence, which does not follow from the rest. In what area of the economy have neoliberals pushed to render government an illegitimate market actor?

It may be a leap for me to say the inroads neoliberals have made in securing state power is built upon the premise (or propaganda) that the government is an illegitimate market actor. But I feel the propaganda has been there for all to see for some time.

Since I was in college in the 80s, I’ve been bombarded with messages that when the government seeks to help its citizens, it leads to worse results, because it distorts markets. (e.g. Reagan: “The nine most terrifying words in the English language are: I’m from the Government, and I’m here to help. “). The welfare state? Regulation? Environmental protection? Affirmative action? I’ve heard or read every one of these blamed for causing or making worse the problems they are intended to ameliorate; all because they interfere with the supposed effectiveness of untrammeled free markets.

The net effect of all the changes to our nation while this rhetoric has been ascendant has not been increased market efficiency, nor has it been smaller government. Instead, we have moved to a system where protecting and promoting the interests of the Boardroom Class are the paramount objectives of the state.

“Free markets” turns out to mean letting rich people do what they want, not promoting efficient allocation of resources through competition and the price mechanism.

“Small government” turns out to means not allowing the government to help anyone the Boardroom Class doesn’t want helped.

“Free trade” turns out to mean subordinating government power to corporate power.

“Lower taxes” turns out to mean shifting the tax burden from corporations and the Boardroom Class to the people the government is no longer allowed to help.

“Deregulation” means externalities are the law of the land, rather than a defect of capitalism that could be ameliorated.

I don’t disagree with the ‘fascism’ label. I just wanted to read out some of the ingredients.

What does any of that have to do with the author’s claim on capitalism? Kotz didn’t say neoliberals appeal to the rhetoric of limited government to mask their true intentions. He also didn’t claim that neoliberals replaced Big Government with Big Business. Rather, he claims that neoliberals support limited bureaucracy – both governmental and private.

Of course authoritarians use language that is part of the culture to justify what they are doing. Vague projection is how neoliberals specifically, and authoritarians more generally, say something without saying anything. You can never hold them accountable later because they never committed to specifics. Sorting out what is authentic and what is propaganda is a pretty basic task of an intellectually honest academic.

I mean, did Kotz support the Immigration and Reform Control Act because it had the word reform in the title? The Financial Services Modernization Act because of modernization? NAFTA because it had free in it? DMCA because digital? The Patriot Act because PATRIOT?

It becomes a silly, navel-gazing endeavor to look at words rather than deeds. The actions are what matter.

I feel like you want an argument, but I don’t see the basis for one.

Identifying the problem is the key step in problem-solving. If that is argumentative, then argumentation is what is required. Big Picture, I think there’s way too much group think in our society.

But here, I asked a pretty short question, and your way of answering that was to go into detail about the propaganda. I don’t think the rhetoric has anything to do with what is actually happening.

So what is the least argumentative way to frame the question of asking for a specific area of the economy where neoliberals have delegitimized government involvement?

Kotz’s entire premise depends upon the definitions he has set up that neoliberals have been limiting bureaucracy rather than embracing it.

You asked me what I meant about legitimizing and delegitimizing different sorts of power. I wouldn’t have gone further into that had you not asked me.

“If we really were in a capitalist system, the state would still actively intervene…” to deter and punish financial fraud, not aid and abet it in the way that the legal and regulatory systems do now. Campaign contributions from the biggest fraudsters, and cost-of-business fines and settlements, have made the regulatory state the bought-off accessory after the fact and unindicted coconspirator enabler of fraudulent financial schemes.

This describes contemporary political economy in that the state’s economic role tends to be largely confined to protection of private property and enforcement of contracts. Find a single bit of financial chicanery that isn’t wrapped up in a shit contract or geared to protect the deeper pocketed side of a dispute, and I’ll find a million that are. Hello protection of private property and enforcement of contracts. Enter Neoliberal State.

It’s all well and good to call bullshit on the bail-outs, robo-signings, illegitimate foreclosures, HAMP runway foam, revolving doors and so on, but it’s naive to suggest these practices are somehow not really capitalist — that true Capitalism somehow doesn’t do bureaucracy and that markets will work fine if we can get the government off honest folks backs and on to policing fraud.

Today’s markets aren’t limited by the state so much as they are limited by monopoly power. The state has recused itself from most everything outside of protecting those monopolies, which makes it easy to see state intervention as bad in itself. So lift that protection — let the banks fail; stop floating douche-bags like Elon Musk; stop foreclosures that lack a paper trail. Somehow have a state that mostly just protects property and enforces contracts without corruption. Then watch the rich get rich, the poor get poor, and the middle class disappear.

It takes money to make money. You can make money in a downturn. Buy low, sell high. Cash is King. Free markets create, sustain, and grow inequality. Theory predicts it, and practice bears it out.

What you’re describing isn’t what people who support market-based economics advocate. If we’re going to redefine capitalism so extremely, that’s a perfectly fine semantics debate to have, but then what’s the point of talking about capitalism?

But that’s not at all descriptive of the state’s role. First, the state does not protect private property and enforcement of contracts. Rule of law has been almost completely replaced by rulers of law. Some are more equal than others. We’ve been talking about a two-tiered justice system for so long it is almost cliched at this point. Second, the state claims enormous powers beyond the legal system. The role of government is so enormous that I am not sure you are thinking this through. We have the largest prison system on the planet. We have the most aggressive national security state on the planet. We have the most expensive healthcare system on the planet. We require documents to go to work or cross the Canadian border or buy medicine. There are banking supports and agribusiness and intellectual property and carried interest tax breaks and home mortgage interest tax breaks and charitable contribution tax breaks and real estate development tax breaks and on and on and on…

Neoliberalism is not the antithesis of capitalism. It is yet another institutional setup that has developed because relatively competitive capitalism is unworkable when it comes to large scale industry. You’re holding out for a form of market-based capitalism that has been completely superseded, and not just by state-based mechanisms. There’s a substantial literature – including work by Nomi Prins, who’s got a post here today, and Michael Perelman, also occasionally appearing here – on how competition in late 19th century capitalism was regarded as too destructive by capitalists themselves, leading to industry consolidations that were eventually bank-driven. Massive investment commitments will not be undertaken if there’s a chance they’ll fail, and the logic of oligopoly is not only straightforward but rational to some degree.

And, while we’re at it, why not at least briefly consider the fate of communities of workers who are supposed to cheerily migrate thither and yon to satisfy market-based criteria of efficiency that equally cheerily ignore their externalized misery? Enter Polanyi and Marx.

I should add that Kotz also talks about the supersession of competitive capitalism in chapter 6 of the book Dayen extracted. Also recommended, a very succinct, useful history.

Did we read the same post? The author is talking about post-war developments, especially the Reagan-Obama era. Government has become much more pervasive in all aspects of the economy, not much less.

Today is 9/11. Are you aware that to this day we are still in a declared, official state of emergency?

Yes, the government has become more pervasive, but on whose behalf? Certainly not the bulk of US society. The government has become more pervasive to the benefit of the very large lobby powers, who pay very large amounts of money to sway congress to do their bidding, and worse, make it look like its all in our best interest.

Agreed. That’s what is so bizarre about Kotz’s claim (from a reality-based perspective).

The question is on whose behalf government power has grown. One way to attempt to deflect attention from that matter is to deny that government power has become more pervasive in the first place.

“the state’s economic role tends to be largely confined to protection of private property and enforcement of contracts”

if you interpret this broadly enough I suppose anything qualifies. But what we actually have going on is not just something quaint like the “protection of private property”, but of course the massive expansion of private property (maybe it was ever thus, cue enclosure discussion). But when they are attempting to patent things that have never been patented like medical procedures as in the TPP, why use such unobjectionable (except to a serious socialist and even they don’t have much problem with personal property) terminology like “protection of private property” to describe what is happening? I mean I could see people who support such things using such language but that is all.

And then you have the bail outs.

Ok only the essay wasn’t about what is and is not “true capitalism” (which I’m not sure is a productive line of thought, but who knows). The essay was making statements that it is very hard to say are true in any sense like:

“Under neoliberalism, non-market institutions – such as the state, trade unions, and corporate bureaucracies – play a limited role.”

and

“However, in neoliberal capitalism the state economic role tends to be largely confined to protection of private property and enforcement of contracts.”

The global economic system needed a multi trillion dollar bailout from the Fed to keep going. How can that fact be reconciled with a statement like that being true. Even the trade agreements which will sell us into slavery depend on state sign off, bought and sold states I might grant, but nontheless.

Would Katz support a radical decentralization and democratization of the modern state as well a massive redistribution of property to private citizens giving everyone a chance to own the means of production?

Or is he going to continue with the traditional lament of bankrupt socialist thinking that since we are apparently unable politically to socialize the means of production we will continue to wax nostalgic about the New Deal and be content with our serfdom–with Big Capital and Big State running the show?

Do you think we will have massive redistribution of property short of revolution? Do you think we need one? Sometimes a BIG does get it’s foot in the door which would somewhat redistribute money and power.

JRS we have already had massive redistribution of wealth. The top 0.01% have never had such gains, in world history.

DOn’t have time now, but the author mis-defines “neo-liberalism”, making it out to be classical liberalism, from which it is actually a stark depaarture. Neo-liberalism isn’t about the state withdrawing from market regulation and leaving it up to “market forces”, but rather about using the state to enforce and expand the dictates of Mr. Market, to the exclusion of any other function. This can be seen in neo-liberalism’s ignoring issues of monopoly and anti-trust, in contrast to classical liberalism’s concern with maintaining competition and suspicion of concentrated economic power..

The un-comparmentalized Titanic free trade model of maximum systemic risk?

Things are not this complicated…For example, the 2008 crisis did not happen in India because the bank head (Rajan?) enforced a mandatory 20% cash down payment (among other things). No real estate bubble in India.

Second, all of this starts with the ability of the banks and the state to create endless money, so companies can make crazy investments. Solution is easy, make it expensive to make new money.

People should have a stake in the game involving real money when buying property (20% down). The problem is wages may have stagnated so much compared to costs that it’s hardly even possible on the wages the vast majority are earning.

“Buying property” = Suburbia, “gentrification,” “development?” These are all behaviors to be credited and encouraged by “policy?” All involving assumption of large debt over long years, and all kinds of externalities and consumptions? And “we” are to protect and foster such behaviors as parts of the Rights of Man?

Always seemed strange to me that “growth in housing starts” is so happily cheered as a sign of a Healthy Economy…

“The most important cause of this change in the financial sector was its deregulation, a key part of neoliberal restructuring, …. A contributing factor was the intensifying competition of neoliberal capitalism….”

Deregulation in a competitive endeavor. Yes. No one thinks taking the referees and umpires off the playing field will result in teams self-regulating during play. Why do so many people buy the nonsense that deregulating the financial competition field will be any different?

I think that if we consider the actual nature of capital, versus our perception of it and how this relationship necessarily evolved over time, it would go a long way toward explaining the economic dynamic of the last half century.

The reality is that capital functions as a glorified voucher system and as such, is a social contract, but we think of and treat it as a commodity.

The divergence is that nothing is more detrimental to a voucher system than large numbers of excess vouchers, but because we individually experience it as store of value, we think of it as a form of commodity to be collected and saved.

Now there were sufficient means to maintain a fairly healthy circulation of capital, from savings to productive investment, up to the 70’s, but then this dynamic started to loosen and the excess capital started seeping into the general economy and it caused inflation.

Presumably Volcker cured this by raising interest rates and thus reducing the flow of extra capital into the economy, but that also further slowed the natural growth and so there was still excess.

It wasn’t until ’82 that this process seemed to start working, but by that time Reaganomics had ballooned the deficit to 200 billion and that was real money in those days. The concern voiced publicly by economists at the time was this would crowd out private sector borrowing and further slow the economy. Yet the reality was only Fed determined interest rates set the availability of capital and the government was borrowing at high rates. So this served various purposes; For one thing, it served to soak up excess capital. It created significant returns for investors and the money was then spent on “Keynsian pump priming,” which helped to get the economy going again.

The lesson apparently learned from this was not to let excess capital back into the larger economy. For one, this required breaking up the labor movement and finding ways to store the surplus within the investment community. Thus the explosion of the power and influence of the financial community, as they were tasked with holding onto an ever growing percentage of the notational wealth of the economy. Along with driving up asset prices and therefore the power of those holding them. The momentum of this naturally knew no bounds and consequently the powers that be have run amuck.

The lesson to learn from this is that wealth has to be stored in something other than notational instruments and excess capital should be taxed back out of the economy, not borrowed back out. This would definitely encourage people to develop all number of mediums of exchange and not rely on banks to store their wealth.

For most people money is saved for very predictable reasons. Raising children, healthcare, housing, retirement, vacations, entertainment, would be some of the most prominent reasons. So rather than storing money in the banking system, communities could build up the infrastructure to support these needs and consequently redevelop a public space. Which would amount to storing wealth in a stronger community and a healthier environment.

So when this bubble does pop, it might prove to have set the stage for an advance in human culture anyway.

As to where things might be going, let us keep thanking Yves for the many contributions to the blogoperspective. Like the series chronicling the “Journey into a Libertarian Future,” http://www.nakedcapitalism.com/2011/11/journey-into-a-libertarian-future-part-i-%e2%80%93the-vision.html Hey, when we got “Government-Like Organizations,” who needs some steeenkeeen’ “state?”

That was by Andrew Dittmer, but yes, I thought it was a great series.