This is Naked Capitalism fundraising week. 329 donors have already invested in our efforts to combat corruption and predatory conduct, particularly in financial realm. Please join us and participate via our Tip Jar, which shows how to give via check, credit card, debit card, or PayPal. Read about why we’re doing this fundraiser, what we’ve accomplished in the last year, and our second target, funding for travel to conferences and in connection with original reporting.

Yves here. As anyone who has been in finance know, leverage amplifies gains and losses. Big company execs, apparently embracing the “IBG/YBG” (“I’ll Be Gone, You’ll Be Gone”) school of management, apparently believed they could beat the day of reckoning that would come of relying on stock buybacks to keep EPS rising, regardless of the underlying health of the enterprise. But even in an era of super-cheap credit, investors expect higher interest rates for more levered businesses, which is what you get when you keep borrowing to prop up per-share earnings. As Richter explains, the chickens are starting to come home to roost.

By Wolf Richter, a San Francisco based executive, entrepreneur, start up specialist, and author, with extensive international work experience. Originally published at Wolf Street.

Companies with investment-grade credit ratings – the cream-of-the-crop “high-grade” corporate borrowers – have gorged on borrowed money at super-low interest rates over the past few years, as monetary policies put investors into trance. And interest on that mountain of debt, which grew another 4% in the second quarter, is now eating their earnings like never before.

These companies – according to JPMorgan analysts cited by Bloomberg – have incurred $119 billion in interest expense over the 12 months through the second quarter. The most ever.

With impeccable timing: for S&P 500 companies, revenues have been in a recession all year, and the last thing companies need now is higher expenses.

Risks are piling up too: according to Bloomberg, companies’ ability pay these interest expenses, as measured by the interest coverage ratio, dropped to the lowest level since 2009.

Companies also have to refinance that debt when it comes due. If they can’t, they’ll end up going through what their beaten-down brethren in the energy and mining sectors are undergoing right now: reshuffling assets and debts, some of it in bankruptcy court.

But high-grade borrowers can always borrow – as long as they remain “high-grade.” And for years, they were on the gravy train riding toward ever lower interest rates: they could replace old higher-interest debt with new lower-interest debt. But now the bonanza is ending. Bloomberg:

As recently as 2012, companies were refinancing at interest rates that were 0.83 percentage point cheaper than the rates on the debt they were replacing, JPMorgan analysts said. That gap narrowed to 0.26 percentage point last year, even without a rise in interest rates, because the average coupon on newly issued debt increased.

And the benefits of refinancing at lower rates are dwindling further:

Companies saved a mere 0.21 percentage point in the second quarter on refinancings as investors demanded average yields of 3.12 percent to own high-grade corporate debt – about half a percentage point more than the post-crisis low in May 2013.

That was in the second quarter. Since then, conditions have worsened. Moody’s Aaa Corporate Bond Yield index, which tracks the highest-rated borrowers, was at 3.29% in early February. In July last year, it was even lower for a few moments. So refinancing old debt at these super-low interest rates was a deal. But last week, the index was over 4%. It currently sits at 3.93%. And the benefits of refinancing at ever lower yields are disappearing fast.

What’s left is a record amount of debt, generating a record amount of interest expense, even at these still very low yields.

“Increasingly alarming” is what Goldman’s credit strategists led by Lotfi Karoui called this deterioration of corporate balance sheets. And it will get worse as yields edge up and as corporate revenues and earnings sink deeper into the mire of the slowing global economy.

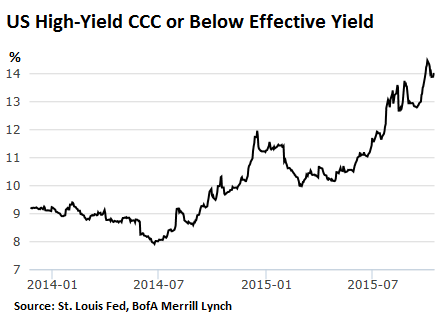

But these are the cream of the credit crop. At the other end of the spectrum – which the JPMorgan analysts (probably holding their nose) did not address – are the junk-rated masses of over-indebted corporate America. For deep-junk CCC-rated borrowers, replacing old debt with new debt has suddenly gotten to be much more expensive or even impossible, as yields have shot up from the low last June of around 8% to around 14% these days:

Yields have risen not because of the Fed’s policies – ZIRP is still in place – but because investors are coming out of their trance and are opening their eyes and are finally demanding higher returns to take on these risks. Even high-grade borrowers are feeling the long-dormant urge by investors to be once again compensated for risk, at least a tiny bit.

If the global economy slows down further and if revenues and earnings get dragged down with it, all of which are now part of the scenario, these highly leveraged balance sheets will further pressure already iffy earnings, and investors will get even colder feet, in a hail of credit down-grades, and demand even more compensation for taking on these risks. It starts a vicious circle, even in high-grade debt.

Alas, much of the debt wasn’t invested in productive assets that would generate income and make it easier to service the debt. Instead, companies plowed this money into dizzying amounts of share repurchases designed to prop up the company’s stock and nothing else, and they plowed it into grandiose mergers and acquisitions, and into other worthy financial engineering projects.

Now the money is gone. The debt remains. And the interest has to be paid. It’s the hangover after a long party. And even Wall Street is starting to fret, according to Bloomberg:

The borrowing has gotten so aggressive that for the first time in about five years, equity fund managers who said they’d prefer companies use cash flow to improve their balance sheets outnumbered those who said they’d rather have it returned to shareholders, according to a survey by Bank of America Merrill Lynch.

But it’s still not sinking in. Companies are still announcing share buybacks with breath-taking amounts, even as revenues and earnings are stuck in a quagmire. They want to prop up their shares in one last desperate effort. In the past, this sort of financial engineering worked. Every year since 2007, companies that bought back their own shares aggressively saw their shares outperform the S&P 500 index.

But it isn’t working anymore. Bloomberg found that since May, shares of companies that have plowed the most into share buybacks have fallen even further than the S&P 500. Wal-Mart is a prime example. Turns out, once financial engineering fails, all bets are off. Read… The Chilling Thing Wal-Mart Said about Financial Engineering

One wonders where all that “investment” goes…pretty much into the CEO’s pockets and investors pockets because banks do not create money by investing in real legitimate capital formation or producing anything tangible…..it spelled out in Micheal Hudson’s – Killing the Host. Economics and investment banking wraps itself in the persona as the engine of growth when, in fact, it is the engine of dis-employment, stagnate wages, declining manufacturing, inflated property prices which raise the cost of food production and everything else including forcing a majority to spend more of their income on debt service leaving less for anything beyond subsistence living. These trillions are wasted and misdirected into useless financial “engineering” as opposed to real world engineering….at the expense of a habitable peaceful planet. Soon, I hope, this dislocation will be corrected. As I have said before, a good start would be to tax that which is harmful (unearned income and rent seeking) and de-tax that which is helpful – real capital formation, infrastructure and maintenance of a habitable planet and the absolutely necessary biodiversity that sustains us.

Because its so much easier to do nothing and make money (aka financial engineering) than it is to do tons of hard work and make money (aka real engineering).

Just the fact that ‘engineering’ is next to the word ‘financial’ makes me laugh these days. I guess everybody is an engineer just like everybody is an associate.

Totally agree. Then there’s the trillions going into engineering for military purposes, serving no purpose outside of intimidation and/or war.

It would be hilarious if the consequences weren’t so tragic.

“trillions are wasted and misdirected into useless financial “engineering” as opposed to real world engineering”

I read yesterday that less than 6% of Bank financing is now going to real tangible assets – the balance goes in various forms to intangible goodwill

this is not “useless” from the standpoint of those who direct this game.

Tony Soprano called it a “bust up” – take over a business and use the brand to skim the profits, buy goods and services and roll them out the backdoor and declare BK and then buy it back for pennies on the dollar.

the money is used for dividends and buybacks all that money is accumulated by the LBO firms and management to maneuver the situation / process to the point of the bust up – this time they are all going simultaneously for the exit even the most high end S&P firm – the HY prices are deteriorating quickly beyond energy related as % LTV goes higher – before 82′ the LTV of Fortune Cos. was way below 20% – 35% was considered max –

the same characters / groups will be formed to get to 51% to buy and control the bonds at 20-30% on the dollar in BK and take the assets.

35 years ago, I spent a day at Ngorongoro Crater in Tanzania with a driver in a rover by myself watching the Hyenas take down a sick Buffalo culling him out in a gang, working the animal for hours, as he shuffled along until he fell and ten….. finally ate him in a ferocious climax. The most fascinating part of the entire trip.

USA, USA, USA !

Goodfellas take on bustin’ the place out, “when its all over you light a match”:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZPtjyqgZAUk

. . .Now the money is gone. The debt remains. And the interest has to be paid,. . .

Now there is a big fat tax deductible expense, and down the road, “value” is created when companies are bought for the tax carry forward losses. Win, win win.

Not to worry. Mrs Magoo at the Fed is already noodling negative interest rates, for her next act. She’ll pay the borrowers to take out loans — only banks and corporations, to be sure. Little people need not apply.

The flip side of paying (big) borrowers to take out loans is that lowly consumers will be obliged to pay the banksters to hold their deposits.

If too many deposits leak out, then cash transactions will have to be taxed or banned to stop the drain. Fatca II can make this happen, comrade.

No doubt it will be sold to the little people as their patriotic duty. “What’s good for Goldman is good for America.”

Deposit all your cash before the mandatory deadline, and receive a free $100 Federal Reserve gift card.

“Companies with investment-grade credit ratings …”

With government-subsidized private credit creation, the whole concept of “creditworthiness” is suspect. Example, is Smith-Wesson “credit-worthy” to many Progressives? Yet, it’s their credit, as part of the public, that would be extended should S&W take out a bank loan.

Is a company that eliminates thousands of jobs via automation or outsourcing worthy of the public’s credit?

At least the investment in automation creates job in that automation in the industrial sense is true capital formation. Outsourcing is just a way to lower labor costs and the cost of the physical plant and land upon which it stands. Asset price increases (land prices) mean that more money is spent on actually puting production on-line and thus more money needs to be put into prices at the sale end to compensate….a bubble in land prices has caused us to be expensive providers of product

It’s not automation that is the problem; it’s how it is/has been financed. Nor is outsourcing necessarily a problem either but gross disparity in asset ownership makes it so.

It turns out that money/credit creation, far from being amoral, is intensely a moral activity.

Whocouldanode?

This is what happens when the Fed keeps rates at zero for seven years – capital gets borrowed and misallocated into share buybacks and other nonproductive uses and the whole thing eventually ends in tears.