Please see the preceding posts in our CalPERS Debunks Private Equity series:

• Executive Summary

• Investors Like CalPERS Rely on ILPA to Advance Their Cause, When It is Owned by Private Equity General Partners

• Harvard Professor Josh Lerner Gave Weak and Internally Contradictory Plug for Private Equity at CalPERS Workshop

One of the striking elements of the November CalPERS private equity workshop for the ostensible benefit of its board was the length to which the giant pension fund was willing to go to distort data and abuse analytical methods to make the case that only private equity could offer the returns needed to meet CalPERS’ performance targets. These tricks were obvious to finance experts, which means that it is almost certain that CalPERS’ staff and the experts on its panel understood full well that they were pulling the wool over the board’s and public’s eyes.

The fact that CalPERS could not make an honest case for private equity suggests that there was no honest case to be made.

Here is a short form dissection of the CalPERS trickery from our illegally-curtailed public comments (more on the violations of the Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act in a future post):

The overarching message of this workshop has been that private equity delivers returns that are superior and are therefore necessary for CalPERS’ investment program. In other words, There Is No Alternative. As a result, CalPERS must submit to various indignities, such as lack of transparency, extremely high fees, one-sided agreements, and outright corruption.

This message is false. There was considerable amount of sleight of hand is at work in these slides, most important in the analysis of returns. Professor Batt touched on that a bit. Due to time limits I can give only a few examples.

First, in the opening section, you implicitly had a new benchmark introduced. The returns were compared against the other asset classes in CalPERS’ portfolio. That’s not how private equity has been presented to the board in the past, nor is it what you will see in the next section when Réal Desrochers presents the annual program review.

If you look in the next section at pages 20 and 21 of his slides, you see that private equity has not met it benchmarks over the last ten years or in any sub-period. Worse, PE not only failed to meet its risk premium, it’s often failed to beat similar stocks. In other words, CalPERS is not being paid enough for the risks it is taking in private equity, and by a lot.

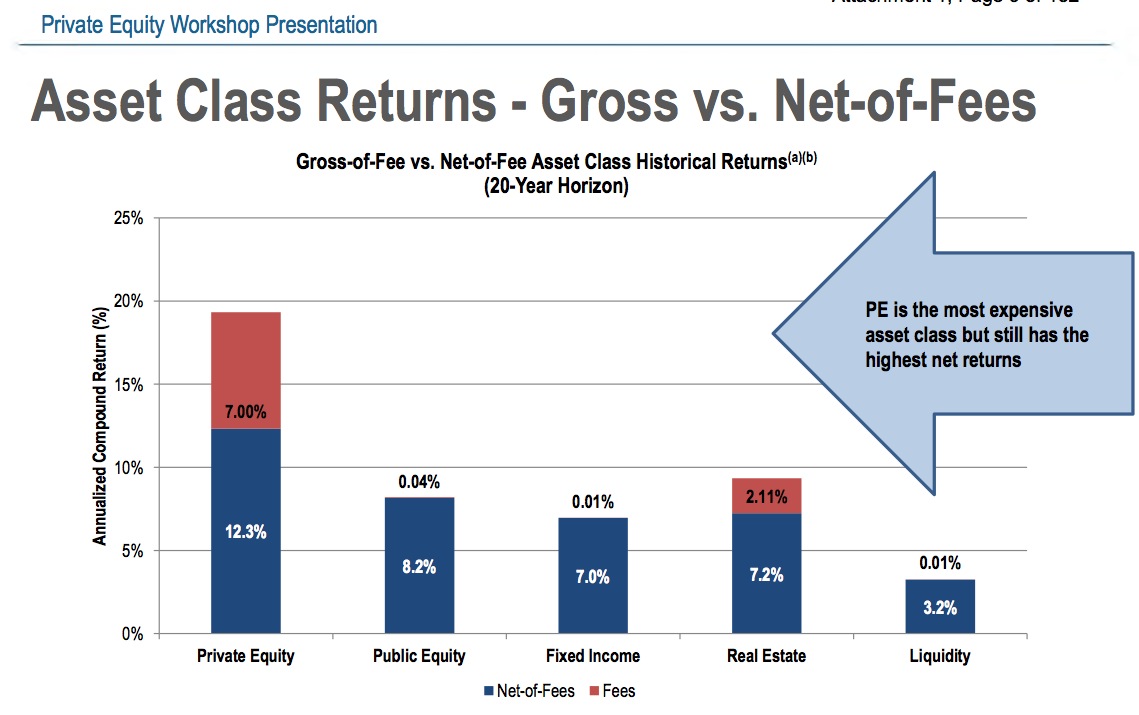

Let’s unpack this a bit. Here is slide 9, one of the three slides in question that makes private equity look like a winner compared to the rest of CalPERS’ options (see slides 8, 9, and 10 here*):

The ploy here is plotting private equity over pages 8, 9 and 10 against CalPERS’ other historical investments. But that’s bogus. From a Los Angeles Times Article by Dean Starkman, CalPERS fee disclosure raises question of whether private equity returns are worth it:

But Eileen Appelbaum, senior economist at the Center for Economic and Policy Research, a Washington think tank, countered that CalPERS’ private equity portfolio has failed to meet its own benchmarks over the last one, three, five and 10 years, important measures that seek to account for the added risk that comes with complicated and cumbersome assets.

“Comparing CalPERS’ private equity returns with the overall returns of the pension fund and/or their target return for the pension fund is meaningless,” she said.

Former banker, now independent private equity researcher Peter Morris elaborated by e-mail:

This slide shows that over 20 years PE (net) has delivered ~400 basis points more than Public Equity. Visually, that looks impressive — but this slide leaves out the issue of how much more PE needs to deliver in order to compensate for illiquidity (as well as other things).

See slide 16: “PE should generate a premium over long term equity returns to compensate for the challenges. Public market index plus a spread reflects the opportunity cost over the long term.”

So where is that premium/spread in the chart on slide 9?

Adding the minimum spread of 300 basis points (3%) to Public Equity in slide 9 shows that in a more meaningful sense, PE (net) has barely delivered what both investors and Lerner believe it should deliver, i.e. a premium over Public Equity. (Beware also of which Public Equity comparison is being used.)

And as Andrew Silton, North Carolina’s former chief investment officer, said via e-mail:

CalPERS shows that PE is the only asset class that beats their assumption, therefore they have to invest in PE. Instead, they should be asking if their assumed return is too high. If a reasonable mix of assets hasn’t beat the benchmark, then the proper step is to question the return assumption, not increase the risk by pursuing more PE.

In addition, anyone who watches financial markets will notice that the returns from CalPERS’ “global equity” portfolio, which is the “Public Equity” shown in its slides, look peculiarly anemic. That’s because CalPERS has a 50% allocation to foreign stocks. Thus CalPERS’ global equity results are lousy due to CalPERS having a currency bet that turned out badly hidden in it. That in turn is used, misleadingly, to bolster the case for private equity. The fact that CalPERS is underperforming in public equities is a problem it needs to address directly and not use as a trumped-up excuse for not asking tough questions about private equity.

We’ll continue to the next section of our remarks:

Second is everyone who presents private equity returns — this is across the industry, this is not, you know, specific to CalPERS — fails to include the cost of accommodating capital calls.

When a limited partner signs a private equity agreement, it doesn’t send the money. It’s a commitment which is… it makes a commitment which is much more like a line of credit. The GP makes a capital call for a specific amount of money and CalPERS must wire it, typically in five to ten days.

The implication of that is that CalPERS must keep the money somewhere to accommodate the capital calls. That means it’s going to be in more liquid, lower return investments. Lower returns in the beginning of an investment period have a disproportionate impact on total returns. Now using typical drawdown periods and generously assuming that CalPeRS puts a high percentage of this money in high-return liquid investments, like your stock index, lowers the return of private equity on a typical fund over the life by 1% to 3%.

Including this cost is devastating to the private equity industry’s claim that the strategy delivers superior returns. Keep in mind that our rough and ready workup was charitable to private equity. Doing the same analysis with actual data is likely to produce results on the high end of our 1% to 3% range, and could even be worse.

CalPERS is capable of performing this computation on their own historical data to get a much more accurate fix on its true returns from private equity. One of our objectives in our 2014 lawsuit against CalPERS was to obtain the data to perform this analysis. However, CalPERS contends that it does not have any records of its commitment dates, save in the signature pages of key private equity documents, and refuses to turn them over, even with all other information redacted save the fund name and the date line. Pray tell, how is the date when CalPERS entered into an agreement, particularly when closing dates are often publicized in trade journals, confidential, much less a trade secret?

Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou has also been interested in this issue. His analysis, using a different methodology, comes to conclusions similar to ours.

If CalPERS cared about understanding if private equity really was a worthwhile investment given its true risks and costs, rather than defending its relationships with general partners, it would undertake this analysis or provide the data to independent parties so they could perform it.

On to the last part:

Third is your volatility assumption. This is critical to the pretense that there is no alternative to private equity. One of the things that Professor Lerner mentioned, sort of a foundational belief in financial management, that high risk/return, that there’s a risk/return tradeoff, that to get higher returns you need to take on higher risk.

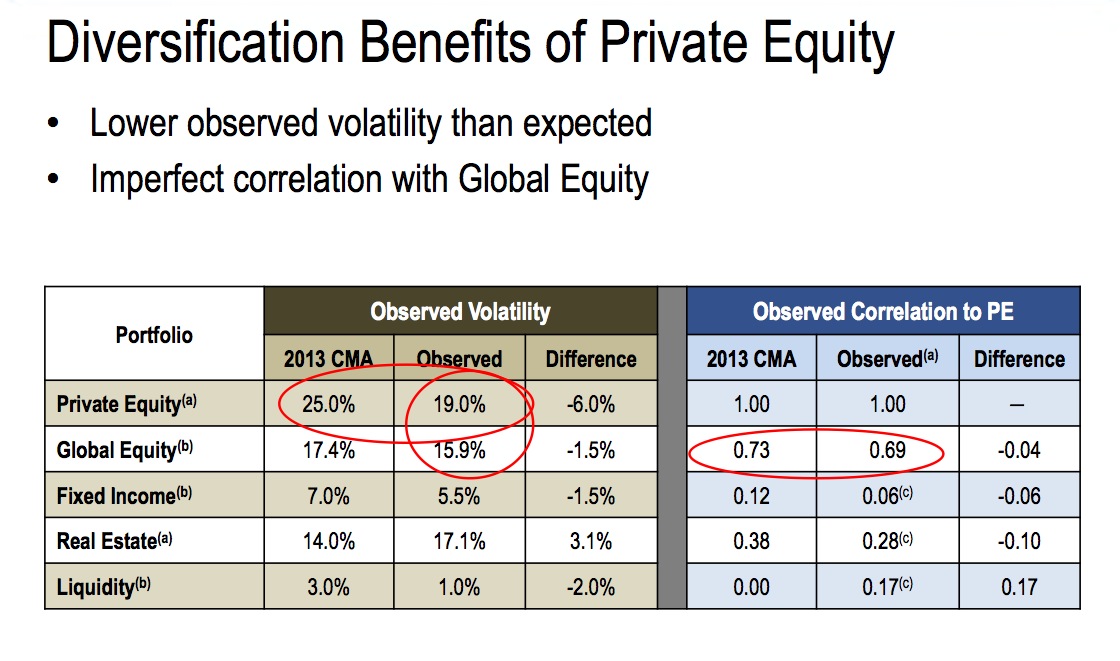

Yet the chart on page 11 shows that, CalPERs, that PE gave a free lunch, that basically that PE provides high returns at comparatively low risk. But if you look at that slide, there’s been a substitution made. At the beginning of the presentation, it used expected volatility. It switches in that slide to observed volatility. Unfortunately, observed volatility is fictitious volatility. Public markets prices are based on real trades. Private equity valuations aren’t. For example, there would have been no bid for most private equity portfolio companies or the funds themselves at the height of the crisis, on September 30, 2008. Yet the reports don’t show that.

You can’t… it’s invalid to use data complied by two different methods to calculate standard deviations or correlations. Yet the slideshow takes the dubious data and plugs it into an optimization model to produce the free lunch result on page 12, and to knock the alternatives to PE on page 15.

And if you think that conclusion is unreasonable, your own consultants, Wilshire and PCA, use higher volatility assumptions, as do top players like Goldman, JPMorgan, and Yale. And those volatility assumptions are based on studies that used actual cash flows from private equity, not the GP valuations.

This part is the most complicated to unpack but it’s also the one that investment professionals like North Carolina’s former chief investment officer Andrew Silton reacted to as particularly misleading.

Volatility is a measure of risk. For instance, if you follow the financial media at all, you’ve probably encountered mention of the VIX index, which is a crude measure of stock market volatility, as a “fear index.” Higher levels of the VIX mean higher perceived risk by investors.

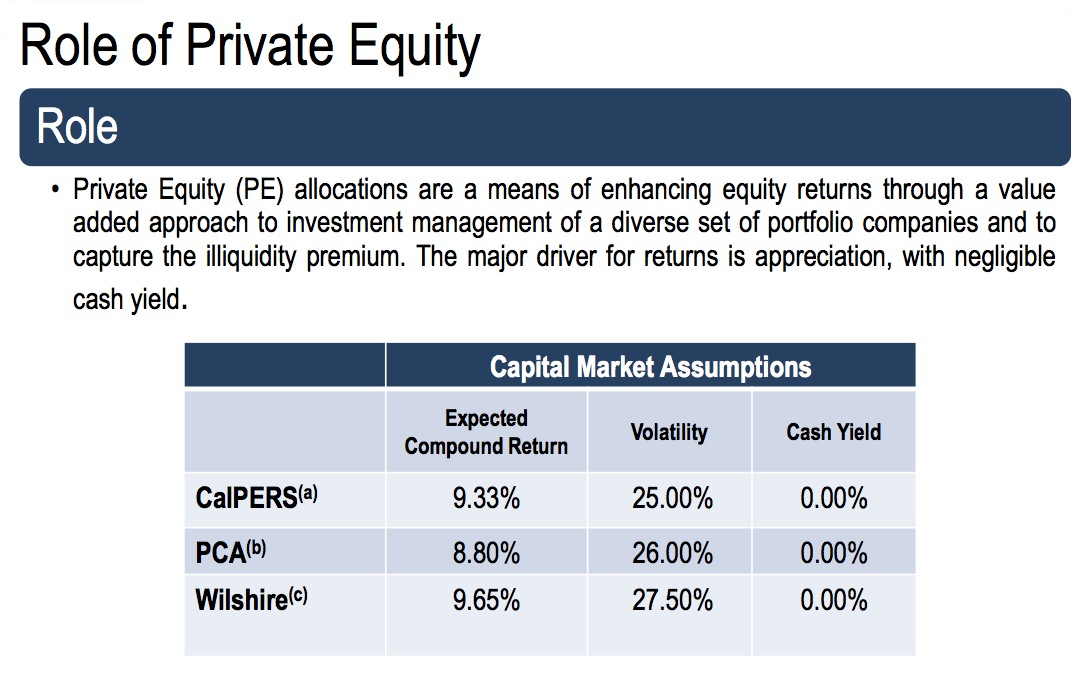

Similarly, higher volatility assumptions mean that more risk is being attributed to the investment strategy. On page 7 of the slides, you’ll see CalPERS present its initial volatility assumption:

If you look at the “Volatility” column, you’ll see CalPERS assumes 25%, lower than the level used by its two independent experts, PCA and Wilshire. So CalPERS is already skewing its assumptions to favor private equity, although not egregiously so… yet.

Here is where the switcheroo takes place, four slides later, where as we described in our talk, CalPERS substitutes the bogus “observed volatility” for the widely accepted, better approximation of “expected volatility.” You’ll also notice the not-all-that high correlation with stocks of 69%. More on that shortly:

Peter Morris explains the implications:

Complicated models are a way for finance professionals to make what they do look more scientific and more precise than it really is. Such models also usually provide a way to come up with the answer you want. Using models like these while ignoring the real world is what blew up the global economy in 2008. CalPERS’s “efficient frontier” exercise isn’t going to blow up the global economy. But it shares the same flaws.

Pretending that private equity fund valuations are as meaningful as stock market prices is just silly to begin with. Going one step further by using so-called “observed” values for private equity is a sign of desperation.

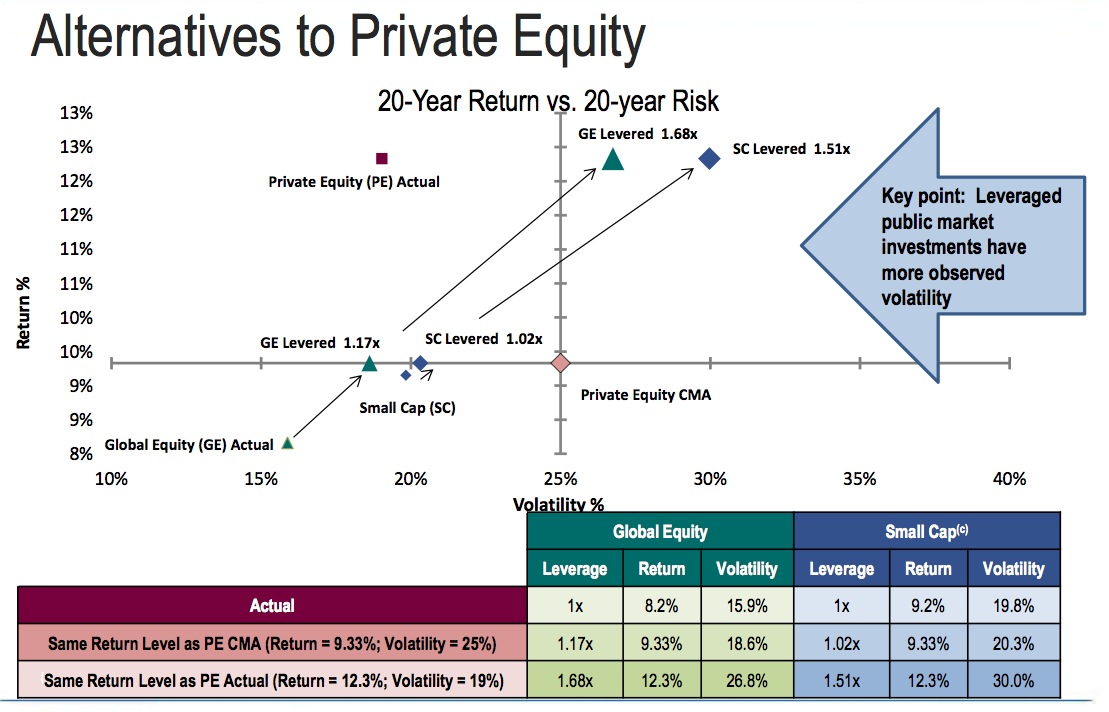

But we can see how flattering using the phony, artificially low volatility figures are on the following slides. For instance, this is slide 15:

By showing that the risk/return lines for “GE levered 1.68x,” meaning CalPERS underperforming Global Equity portfolio levered 1.68 times, and “SC levered 1.51x” meaning a small-cap stock index levered 1.51 times, are both to the right of where the “PE (actual)” red box sits. That means that CaLPERS staff is claiming that private equity is clearly superior by virtue of offering better returns at lower risk.

But the reason that private equity is located so far to the left is that they’ve used the phony “observed vol” assumption of 19%! As Peter Morris explains:

But slide 15 shows why this gimmick is necessary. It’s the only way CalPERS can “prove” that (net) private equity returns are more valuable than investing in the stock market with financial steroids.

Slide 15 argues that PE provides better risk/return than levered public equities. I don’t see any description of where the levered public equity figures come from. But the main point is that this argument rests entirely on the difference between Capital Markets Assumption volatility of 25% and “observed volatility” of 19% (slide 11).

Using the CMA vol assumption of 25% would move “PE Actual” significantly to the right in slide 15. PE Actual would end up virtually on top of GE Levered.

And remember, that CMA 25% assumption is lower than the ones provided by CalPERS’ own hired guns, PCA and Wilshire. And it is also lower than the result found in an important paper by Ang, Chen et al., using actual limited partner cash flows, which again shows volatility higher than the CalPERS 25% CMA assumption. Goldman is using the assumptions from this paper for their current private equity modeling. The authors are making the data in this paper available, and it also shows a much higher correlation of private equity returns to the stock market, of 90%, versus the 69% “observed,” which again knocks out another of the supposed advantages of private equity, that of only moderate correlation with listed stocks.

Peter Morris teased the real story out of CalPERS slides, one curiously absent from the workshop:

Slide 9 tells the real story of what’s going on in private equity. Historically, private equity managers have generated quite high (gross) returns. Ignore for the moment the tricky question of where these returns come from. But these gross returns are all before the managers start extracting their multiple and opaque varieties of fee. It’s revealing that in slide 15 CalPERS can do no better than estimate (at 7% per annum) the annualized cost of the billions of California taxpayer dollars it has been handing over to private equity managers for the last twenty or more years.

Even so, slides 15 and 9 make it easy to see what CalPERS and other private equity investors have collectively achieved over the last 20 years. They have made a small number of private equity managers very rich. Meanwhile, their own members (along with taxpayers in many states) have done no better than they could have done by using artificial boosters (extra debt) on the stock market.

Slide 15 shows that private equity managers currently get to extract most of the juice in their (gross) investment returns for themselves. That leaves CalPERS with a leveraged play on the stock market.

Here is the right response. If CalPERS is happy with a leveraged play on the stock market, it should look for cheaper and more convenient ways of getting it. Finance is chock full of clever financial engineers who will be only too happy to help. The other alternative is for private equity managers to reduce their fees and return a more appropriate share of their profits to the investors whose money actually lies behind all this. The current terms of trade in private equity reflect a betrayal of fiduciary duty.

To put it more tersely, as Morris did later, “‘LPs are allowing themselves to be ripped off.’ That perfectly describes CalPERS’s slide 15.”

And the costs go well beyond merely making private equity barons rich. The very investors who amassed their wealth on the back of public pension funds often reinvest their lucre in a frontal attack on those very institutions. For instance, from yesterday’s New York Times (hat tip DO):

Mr. [Kenneth] Griffin and a small group of rich supporters — not just from Chicago, but also from New York City and Los Angeles, southern Florida and Texas — have poured tens of millions of dollars into the state, a concentration of political money without precedent in Illinois history.

Their wealth has forcefully shifted the state’s balance of power. Last year, the families helped elect as governor Bruce Rauner, a Griffin friend and former private equity executive from the Chicago suburbs, who estimates his own fortune at more than $500 million. Now they are rallying behind Mr. Rauner’s agenda: to cut spending and overhaul the state’s pension system, impose term limits and weaken public employee unions.

In other words, public pension funds are naively signing their death warrants, and that of the pay packages of state employees who have not yet retired, out of their deeply misguided, utterly unwarranted loyalty to the private equity industry.

Yet rather than recognize what their own data is clearly telling them, CalPERS, like most private equity investors, lies to itself and the general public about the necessity and virtue of private equity. While the lie that is the most critical to this pretense involves investment returns, there are plenty of others, and we’ll turn to them in the next posts in this series.

___

* Since we run the risk of exhausting the patience of our readers, we are debunking only the most glaring distortions made by CalPERS’ staff and outside experts. But we’ll note a few additional ones on these pages just to give you a flavor of how extensive the gamesmanship was. Slide 9 uses the most flattering time frame, 20 years, when as we point out later in the post, even academics who have been staunch supporters of private equity are issuing “the past is not necessarily a predictor of future performance” warnings. And the results themselves show that, that in an extended period of disinflation that has now hit its ZIRP limits, and as more dollars have been chasing private equity deals, the returns have been deteriorating. With PE firms paying peak-of-cycle multiples, there is no reason to expect PE to show its 1990s level of performance any time soon, if ever. And slide 9 also uses the 7% estimate of total fees and costs from Ludovic Phalippou, when at this point, CalPERS clearly had better data by virtue of having gotten historical carry fee data from its general partners in July. One has to assume CalPERS continued to use this estimate rather than actual results because the estimate was less detrimental. Similarly, on p. 11, we again have the misleading 20-year time frame used, and charts of this sort are visually misleading unless they are plotted on a logarithmic scale.

Having recently joined the pensions industry in the alternatives space, these articles are tremendously helpful. Thanks.

Thanks so much for telling me. It’s gratifying to hear that these posts are making a difference on a practical level.

Number one rule of the financial industry — everybody lies, and every recommendation oh-so-coincidentally puts the most money in the storyteller’s pockets. They start with the goal — PE offers more lucrative commissions — then work backward to justify with stats and charts why PE is the greatest thing since sliced bread.

That strikes me as the core systemic problem with public pensions. If we decide that retirement is a public good, then it should be funded by taxation, not financial returns. The concept of central planning is flawed. Public institutions are terrible at allocating private capital, whether we call them “performance targets” or “five-year plans” or “securities held outright”.

Great post. I’m being to wonder what is the exact nature of the CalPERS staff’s relationship to PE general partners, what does does that relationship amount to?

My patience is not taxed. My interest in increasing. Each post makes me wonder “what next”?

Thanks so much for your continued reporting.

This is a key question and not easily explained in a short space. Here are some components in no particular order:

Investors like CalPERS are afraid of the GPs, which may seem bizarre given that the investors have the money and in pretty much any context, that confers at least a fair bit of power. But the GPs now are the biggest source of business to investment banks, the biggest source of fees to top law firms. The investors can’t get access to the same caliber of legal advice that the GPs get, even when they go to the same firms. in that everyone buys into the idea of not ruffling the GPs or challenging the basic power dynamics of GPs because the various advisors don’t want to lose business. For instance, if a fund consultant (and remember, fund consultants don’t have GPs as clients) were to ask tough questions about private equity, you can imagine in not much time that GPs would start calling investors and telling them that the consultant was a time waster, didn’t understand the business, etc. And they’d be fired in pretty short order

GPs also are generally of a higher socioeconomic status than investors, and this is not by virtue of them being rich. They almost without exception went to better schools.

There is virtually no revolving door between GPs and investors. You can count on one hand and have fingers left over as to how many people have gone from an investor to a GP (and ironically one of those exceptions come from CalPERS, Rick Hayes, its former head of PE. And he had gone to the “right” schools). However, LPs believe it is to their career advantage to make nice to GPs, that they could put in a nice word or open a door when they are looking for their next job.

Unlike the other asset classes in which CalPERS invest, the people in PE go on nice junkets. The industry conferences are held in nice locations, and each investor has an annual meeting (and the money comes out of the fund, it’s a fund expense) with lots of wining and dining and at the big funds, big ticket entertainment.

This is from the former CIO of North Carolina, Andrew Silton:

http://meditationonmoneymanagement.blogspot.com/2015/09/how-calpers-private-equity-team-may.html

Hope that helps.

And yet, that’s exactly how capture works. That is basic relationship building which ties into the later points about ego and reputation. Accidentally spilling secrets and using the formality of meetings to increase the contrast to the real connection made after hours and so forth. It also helpfully removes the senior staff from their constituents: it reinforces them thinking up instead of down. Those dinners and drinks and golf outings and conferences and hotels and whatever are not to be thought of as outrageous expenses; they’re merely par for the course, if you will. Not even worth getting excited about. Except make sure it’s a nice restaurant; wouldn’t want to be seen at McDonald’s.

An exceptionally public-minded pension manager can use such relations for the benefit of the fund, of course, but in aggregate, the general effect is to create more partnerships than adversarial stances.

Especially since so many of the top pension managers are extremely well paid relative to what the typical worker makes. Eliopoulos, for example, is a Dartmouth grad who worked previously in the state Treasurer’s office and received total compensation from the state of California of over $800K last year. We’re not talking about typical workers; we are talking about various levels of the most highly paid employees in the nation.

It would be interesting to know where the 19.0% observed volatility for private equity comes from. In some slides from a CalPERS PE consultant’s presentation a few months ago, volatility wasn’t even mentioned.

Because of the complications introduced by cash flows (contributions and distributions), a “chained modified Dietz formula” is used to derive volatility, given a series of quarterly NAVs. As the European Private Equity and Venture Capital Association drily notes (page 16),

Given CalPERS lack of interest in volatility in the past, one might guess that the 19.0% observed volatility is derived from a generic industry index rather than CalPERS’ actual experience (though I’d be glad to be proven wrong).

Show us the math!