Yves here. Nicholas Shaxson summarizes a very important study, which finds that corporate tax cuts lead to cash hoarding, which lower growth. Moreover, this cash hoarding started in the 1990s, which is just before the famed Bernanke “saving glut”. We’ve disputed his claim that it played the role he suggested in the global financial crisis (the best debunking of that idea is in a paper by Claudio Borio and Petit Disyatat of the Bank of International Settlements, Global imbalances and the financial crisis: Link or no link?” (see Andrew Dittmer’s translation for laypeople here). However, we’ve been calling attention to corporate dis-saving, as in liquidation rather than investing, since 2005, and cash hoarding and stock buybacks are part of this pattern.

By Nicholas Shaxson, the author of Treasure Islands, an award-winning book about tax havens. Originally published at Fools’ Gold

Recently Prof. Matthew Watson wrote an article for us entitled The Anti-Growth Dynamics of the Competitiveness Agenda, in which he outlined generic reasons, both from a supply side and a demand side, where supposedly ‘competitive’ policies on wages and in other areas are likely to depress economic growth.

Now a new study from the Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) complements this and notes something more specific that we’ve remarked on previously: that ‘competitive’ corporate tax cuts are likely to be equivalent to pushing on a string. They will tend to feed corporate cash hoarding (what Mark Carney has called ‘dead money’) instead of business investment – while sucking revenue and investment and spending power out of the government sector, depressing demand and investment. The likely result is slower growth.

How does this stack up, from an empirical perspective? Well a new blog from the Tax Justice Network constitutes good supporting evidence for the proposition that ‘competitive’ corporate tax cuts depress growth.

New Study: Corporate Tax Cuts May Have Been ‘The Greatest Blunder’

The Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives has just published a new study entitled Do Corporate Income Tax Rate Reductions Accelerate Growth? It summarises:

This study examines the relationship between the Canadian corporate income tax (CIT) regime and various dimensions of economic growth. The author finds that CIT cuts have not only failed to lead to faster growth, but there is evidence to suggest that—far from spawning higher levels of business investment and GDP growth—corporate income tax reform has indirectly fostered slower growth.

Box: New Australian study

The Sydney Morning Herald has an article today entitled Company tax cut a bonanza for big end of town, analysis shows.

That study, from the Australia Institute, finds that cutting the corporate tax rate from 30 to 25 percent would mean:

- Federal Government revenue would fall almost $27 billion in a decade

- Australia’s four largest banks would gain $2 billion in just one year.

- Based on projections from 2015, just two of Australia’s biggest coal companies combined would stand to gain $9.3 billion in ten years.

- Australia’s top 15 listed companies would receive $58 billion in the decade ahead with minimal benefit for the wider economy.

- Many benefits of the tax cut would not accrue in Australia instead flowing to foreign shareholders and foreign tax authorities.

- Analysis of the some of the companies concludes that none are likely to significantly change behaviour as a result.

- There will be more incentives for high-income individuals to avoid income tax by incorporating.

Which is in line with our document Ten Reasons to Defend the Corporate Income Tax, which (along with plenty of evidence) contains several key arguments why corporate taxes are essential for economic growth.

The CCPA study contains this striking conclusion:

If the findings contained in this paper are true, then corporate income tax cuts will go down as one of the great Canadian public policy blunders of recent times.

In more detail, the study explains:

By plotting the empirical history of, and statistical association between, three CIT rates—the effective federal rate, the combined statutory rate, and the weighted average effective rate on the top 60 Canadian-based firms—and five growth variables—business investment in fixed assets, private sector employment, GDP per capita, labour compensation, and productivity—the paper concludes there is no empirical or statistically significant relationship between CIT regime and growth.

Of the 52 tests of association, 38 (or three-quarters) are not statistically significant. In the roughly one-quarter of cases where there is a statistically significant result, the direction of the effect is more often positive than negative—the opposite of what neoclassical economic theory predicts.

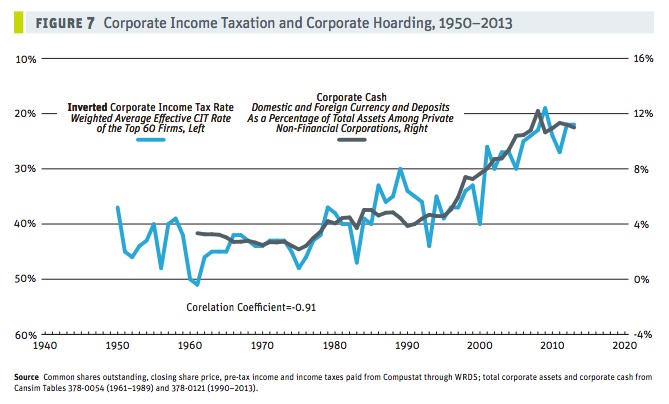

Neoclassical theory says that corporate tax cuts should feed through into more business investment, and hence higher growth. In practice, however, they have been feeding through into corporate cash hoarding: what the then Bank of Canada Governor Mark Carney in 2012 called “dead money.” Here is a striking correlation illustrating the trend. (Note that the corporate tax rate is inverted.)

The CCPA summarises:

There is an incredibly tight, persistent and negative relationship between the level of corporate cash and the CIT rate. With every reduction in the CIT rate, corporate Canada stockpiled an ever-greater proportion of cash on its balance sheet rather than investing its enlarged earnings into expansionary industrial projects.

Corporate cash hoarding is a worldwide phenomenon, linked to rising inequality, and in this environment corporate tax cuts are likely to be the equivalent of pushing on a string: if the investment opportunities aren’t there then corporations will simply transfer their tax cut bonanzas into bigger cash piles, while sucking away the state’s capacity to invest in teachers, roads and so on. In this view, growth is likely to suffer.

The empirical and statistical facts stubbornly refuse to support mainstream economic thinking on this matter. . . the facts stubbornly refuse to support the notion that corporate tax cuts accelerate growth.

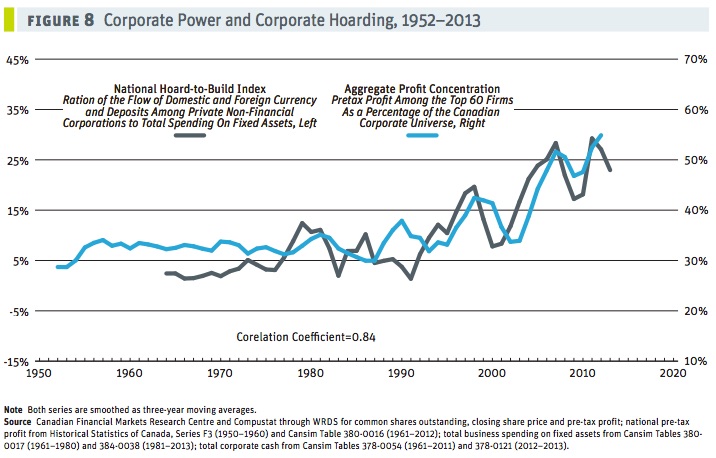

And the CCPA makes another interesting argument, prefaced with a reference to the economist Thorstein Veblen. This is about large corporations, market power, oligopoly and monopoly.

It seems plausible that as a small cluster of large firms increase in size and market power, they pull away from the rest of the corporate universe in terms of cohesiveness, business behaviour, political activities, etc.

And if these large firms hoard relatively more cash than small firms do, then this increased concentration of large multinationals is likely to damage growth, via more cash hoarding, and as firms focus more on mergers and acquisitions rather than genuine new investment (for which they need to hoard cash in advance).

If these large firms stockpile a larger quantity of cash, it may be that the growth of large firms itself figures heavily in corporate hoarding, and exacerbated cash hoarding may be a key driver of stagnation.

Is this happening? Are large corporations driving cash hoarding? Well, here’s another suggestive and rather tight correlation:

They add:

We can therefore say with confidence that the CIT [Corporate Income Tax] regime is one element of the twin processes of heightened corporate concentration and slower rates of growth. It does not need to be stressed that this set of claims goes against orthodox economic thinking. Nevertheless, the facts support these assertions, which should make them candidates for economic truth.

And we should note something else. The real take-off point for all this cash hoarding, as this and other graphs in the study show, was the early to mid 1990s. This coincides with the timing of a sudden surge in “corporate profit misalignment” (a fancy term reflecting multinational corporate tax dodging,) which we recently highlighted in a fascinating study by TJN authors at the International Centre for Tax and Development (ICTD). Admittedly the data isn’t directly comparable between the two studies, but this coincidence of timing supports the ‘pushing on a string’ theory of corporate tax cuts and clearly warrants deeper investigation.

So how do we explain so much academic and political opinion in favour of corporate tax cuts, beyond the lobbying? Well, one major factor is that a large number of studies focus on the relationships between corporate taxes and private investment, rather than between corporate taxes and growth. And corporate tax cuts do seem correlated with some measures of private investment, as one would expect (but even so, one then gets into the question of what kind of investment one is talking about: investment into genuine new productive activity, or into unproductive real estate speculation, or often wealth-extracting mergers and acquisitions, or what.)

But always remember this crucial fact: private investment, from a tax policy perspective, is merely a means to an end: it’s ultimately balanced, sustainable growth that you’re after. If private investment is obtained through cross-subsidies extracted from the public sector (which is itself an investor) then you may be back where you started — or worse, if the public sector is doing a better job at investing than the private sector is. This seems to be the case with today’s stagnant, cash-hoarding economies; and an aside let’s not forget the work of the likes of Mariana Mazzucato in this area. So the studies looking at private investment may be little more than interesting academic abstractions.

Again, our Ten Reasons document looks at this in more detail, particularly Section 7: A Tool for Rebalancing Distorted Economies.

The CCPA study focuses on Canada. But as our Ten Reasons to defend the corporate income tax document demonstrates, the evidence and arguments made here are replicable in many countries around the world.

(This article will be stored permanently in the “Harms” section of our website.)

I have been arguing for a long time that corporate tax on profits should be abolished (gasp), but at the same time, a corporate tax on retained cash (well, liquid assets) over and above say twice working capital requiremnts introduced.

It’s not as easy as I make it sound here, but I believe it would set much better incentives than the current system.

Of course, tht would require realisation that taxation is not mainly money raising instrument but incentive instrument. fat chance of tht happening anytime soon..

taxing existing wealth, an idea that politicians pretend doesn’t exist

Because that idea is anathema to the oligarchs.

Cutting CIT? Ask governor Brownshirt, er, Brownback of Kansas how that’s working out.

(Hint: million$ cut from the state education budget trying to plug the revenue gap)

+100. State budget is a disaster for education, roads and bridges, state administered childrens’ health care, state privatized medicaid services, general public services, and county and city budgets – lege has scooped up traditionally county/city generated revenues.

Ah, the things we do for “growth”! A dog chasing its tail.