As we said at the start of our Bloomberg op-ed, Calpers Can’t Eliminate Risk by Ignoring It, which ran yesterday:

What would you think if a pension fund responsible for 1.7 million beneficiaries said it was going to stop considering the the riskiness of one of its biggest investments?

Incredibly, that’s what the board of the California Public Employees’ Retirement System, America’s biggest public pension fund, might do on Dec. 14. One item on its meeting agenda would eliminate the strategic objective to “maximize risk-adjusted rates of return” on private equity, which involves using large amounts of debt to buy out companies with the aim of reselling them at a profit. This is a major policy change, engineered by the people who manage Calpers’s private equity investments.

Pay attention, because this is a case study in how CaLPERS’ staff manipulates the board to its own advantage.

CalPERS is apparently making this change in response to its poor performance in private equity over the last ten years. So CalPERS is acting like a fat person who decides to throw out the scale rather than look at its weight problem. And its enabler, its private equity consultant Pension Consulting Alliance (“PCA”) hasn’t even attempted to muster an intellectual justification to the board for this change. In a September board meeting at CalPERS’s Sacramento sister, CalSTRS, another PCA client, the account manager for both funds, Mike Moy, blandly acknowledged that private equity investors have a performance problem but then blamed the benchmarks!

The result of ignoring or even just underestimating risk is that investors will put far too much money in risky strategies. We’ve seen this movie again and again, from dot com stocks, to subprime debt and CDOs, to sovereign debt, to name a few. It’s bad enough to suffer the high costs of flawed risk measurements systems (or worse, having clever staffers game the system to fatten their pay packages). It’s insanity to choose to fly blind on risk. Yet as we’ll demonstrate, that appears to be what CalPERS intends to do.

Don’t kid yourself that this is just a California matter. As we’ve stressed, when CalPERS makes a policy change, it often moves the entire industry. We’ve seen that operate in a positive way in the past. For instance, when CalPERS was required as a result of a settlement with the San Jose Mercury News to disclose some key elements of private equity return data, other public pension funds became less secretive. Similarly, now that CalPERS has disclosed the carry fees it has been paying, experts expect other funds to follow. For instance, Chris Flood wrote in the Financial Times last week that CalPERS’ Sacramento sibling, CalSTRS, is under pressure to gather and disclose the same information. The Missouri and New York City pension funds are already seeking the data.

But CalPERS has the power to lower the bar as well as raise it, and that is in danger of happening this Monday, December 14, at its Investment Committee meeting. And with similar plans afoot at CalSTRS, the indefensible precedent that is about to be put in place at CalPERS, which is intended to make private equity performance look better than it really is, could rapidly become the new normal.

And if you are as disturbed by the idea that private equity, which is clearly riskier than other major types of investment, should get a free pass on risk, please alert friends and colleagues in California today and get them to voice their concerns to the state Treasurer, Controller, assemblyman, and senator. Contact details are at the end of this post. Let me stress that every, and I mean every, economist, finance professional and educated layperson I’ve contacted is appalled by this pending switch.

And what is the most likely motivation for this change? Staff bonuses. Most pension fund managers base a portion, often a substantial portion, of their bonus formula for investment staff on investment performance. Needless to say, with private equity having underperformed the typical benchmarks of a stock index plus three to four hundred basis points (3% to 4%) over the last ten year for most private equity investors, there are a lot of employees and officers, particularly ones in funds big enough to have private equity specialists, who can be assumed to have gotten thin bonuses at best for quite some time. It’s not hard to imagine that they’d be pushing hard for measurement changes that would make it easy for them to say they were performing well and hence should be paid more, particularly if CalPERS and CalSTRS legitimated the shift.

Background: The Importance of Risk Measurement in Private Equity

The idea of a “risk/return tradeoff,” that higher risk investments need to offer more in the way of potential return to justify investing in them, is one of the fundamental principles of finance. That does not mean that investors always get it right, as asset bubbles prove. But ignoring or underestimating risk is a sure-fire path to bad results, as numerous examples, such as AIG and LTCM, attest.

Conversely, firms that have superior acumen in risk management often improve their competitive position. Bankers Trust’s CEO, Charles Sanford, developed the path-breaking concept of RAROC, or “risk adjusted return on capital” which is now widely embodied in various newer incarnations in banking. This management tool helped propel Bankers Trust from being just another mid sized New York City bank to an industry icon until its derivatives traders’ propensity to rip off clients led to its fall. JPMorgan similarly gained competitively through its development of the Value at Risk model, the brainchild of CEO Dennis Weatherstone. JPMorgan persuaded the Fed to promote as an industry standard. Unfortunately, while VaR was a big advance at the time, its deceptive simplicity had stymied the development of better approaches, since regulators in particular liked VaR, and better techniques often require more mathematical acumen than they have to use them well.

As readers may recall, investors in private equity have long measured private equity returns using a target based on a stock indices, plus a premium of 300 to 400 basis points to reflect the idiosyncratic risks of private equity, namely, its illiquidity and considerably greater use of borrowed money than in pubic companies.

The effort to compare private equity to a comparably risky public stocks, plus some sort of risk premium, is sound. There are admittedly problems with how private equity valuations are reported (general partners make their own estimates; there are times when the valuations are generally overstated), but those difficulties reinforce the underlying issue: that private equity is riskier than public equities, and worse, riskier than the reported data would lead you to believe.

It is fair to question whether the typical premium of 300 to 400 basis points is the right premium, or even the right approach (would a percent of the return level be better, say, 140% of the return of comparable stocks?) Yale, which is widely considered to be a leader and has enjoyed sparkling results, uses an even higher risk premium of 450 basis points. Former North Carolina chief investment officer Andrew Silton similarly argues for higher risk premia.

We’ve pointed out that the typical 300 to 400 basis point premium is a mere heuristic, and have also advocated more rigorous approaches to measuring risk (the limited partners have given the general partners valuable options: the right to call the funds, and the option as to when they make distributions, and it should be possible to make rough estimates of the value of those options and compare them to the current rules of thumb).

But irrespective of the argument over methodologies, it is universally accepted that it is possible to rank the riskiness as higher than that of public equity. . This is the core argument for demanding a premium to public equity. And as we will see, CalPERS appears to be planning to end this well-accepted practice.

CalPERS’ Proposed Changes to Its Investment Policy for Private Equity

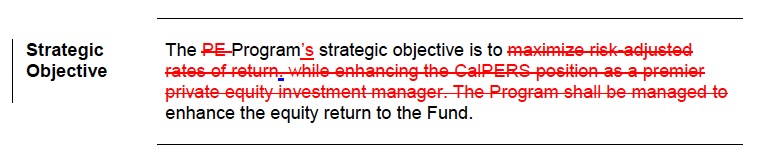

We’ve embedded Item 7a, which is to be voted on this Monday, at the end of the post so interested readers can see the document in full. Below is the critical change:

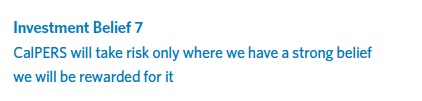

Notice how the elimination of consideration of risk flies in the face of one of CalPERS’ “Investment Beliefs“:

If you eliminate the idea of risk, what do you have left?

CalPERS has been thinking about measuring private equity on a more permissive basis since at least 2014. The giant pension fund and its consultant PCA have been giving hints, at least if you’ve been paying close attention, about their ideas:

Chief Investment Officer Ted Eliopolous: And as was highlighted in last December’s Private Equity Program review, private equity does have, and clearly has, some characteristics that are clearly aligned with CalPERS Investment Beliefs, such as our long-term time horizon, and our willingness to take risk where we expect to be adequately rewarded. Over the long term, our Private Equity Program has generated absolute returns in line with our expectations. Currently, private equity is the only asset class in our portfolio that is expected to exceed our seven and a half percent target rate of return on a net basis. As such, private equity remains an important component of our portfolio and the overall sustainability of the CalPERS system.

You’ll see how Eliopoulos abjectly misrepresents private equity’s underperformance for the last ten years by saying it has performed “in line with our expectations”. Pray tell, how is underperforming your benchmarks by hundreds of basis points in line with expectations?

But catch the finesse: Eliopoulos has already introduced a new benchmark, that of “absolute returns,” one not approved by the board or used in CalPERS’ private equity program reviews. And as we pointed out in a later post, PCA’s account manager Mike Moy gave its Consultant Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to Eliopoulos’ remarks, a strong indicator that PCA and Eliopoulos had crafted this language in advance.

Moy was more explicit about PCA’s support for the barmy “absolute return” idea at a presentation at CalSTRS. From a September post:

The very fact that CalPERS’ private equity returns over the past decade have been hundreds of basis points below CalPERS’ benchmarks says that private equity falls massively short in giving enough return relative to the risks involved. Shorter: Private equity cannot be depicted as as sound investment.

So how does PCA propose to deal with this glaring problem? By refusing to measure it any more. No measurement, no problem, right? Here is the fix it recommended to CalSTRS:

Mike Moy, Pension Consulting Alliance: You will notice in the report the continuing difficulties that we have with the benchmark and your performance against that benchmark. I would argue that the problem is the benchmark, not the performance. But I think that’s, to me, an industry-wide problem, in finding an appropriate benchmark that really gives you the ability to measure success currently and in the long term. I think you really have to look at it on a absolute basis to make certain that it’s contributing to your expected performance that’s in your asset allocation.

If you are finance literate, what Moy is trying to sell is utter sophistry. Whether by accident or design, he reveals what the benchmark gimmickry is really about. It’s not to measure performance, but to measure “success currently and in the long term.” Thus anything that conflicts with the real agenda, that of depicting private equity as a success no matter what, must be replaced with something that does.

“Absolute returns” is a totally unsuitable framework for evaluating private equity. We’ve attached an article at the end of this post that debunks the myth of absolute return investing. A money quote:

Just because something is called an “absolute-return investment” does not mean it is granted an exception to the first law of financial gravity described in the previous section: The returns of any portfolio can be broken down into market (beta) components and an alpha [manager skill] component. So, here is the money question we are asking all hedge fund managers who fancy themselves absolute-return investors: Is the expected return you offer investors attributable to your expected average exposure to the beta (single or multiple) that characterizes your normal portfolio, or is it attributable to expected alpha generated through skillful beta timing or security selection?

It’s simply ludicrous, and therefore a sign of general partner and private equity consultant desperation, to try to fit private equity into an ‘absolute return” framework. “Absolute return” strategies, to the extent they ever could be achieved, sought to beat the market in good times and preserve capital in bad times, as in not lose money or at least lose less money than “the market” (however you wind up defining it) overalll….

As Oxford professor Ludovic Phalippou said via e-mail (emphasis ours):

I have commented on this issue of the need to benchmark private equity against public equities for years and made that point countless times. And I believe that financial economists are unanimous on this issue.

The simplest reason why PE returns need to be benchmarked against listed equities is because once a PE fund buys a company, the price is in line with similarly traded companies. The same is true when the PE fund sells it. Hence, a PE fund did nothing to create value if an investor would have earned the same return as similar listed stocks. That is why it is a benchmark.

A more elaborate answer is that all of the empirical evidence we have accumulated indicates that the correlation between listed equity and PE returns is very large (at least 80% correlation).

An absolute return benchmark, i.e. risk free rate, is absolutely unjustifiable on any ground.

From Eileen Appelbaum, co-author of Private Equity at Work:

Mike Moy notes PE’s “continuing difficulty with benchmarks” – an apparent admission that private equity is failing to meet CalSTRS’ benchmark. His conclusion is stunning – the problem, he says, “is the benchmark, not the performance.” Try telling that to your boss the next time you get a poor performance rating!

Unbelievably, Moy’s solution to the difficulty with benchmarks is to get rid of them altogether. Of course, he doesn’t say so outright. What he does say is that PE returns should be looked at “on an absolute returns basis.” The advantage of doing this? An absolute returns strategy is not benchmarked against a traditional stock market index but against a risk-free benchmark like US Treasuries, or against no benchmark at all. The goal of such a strategy is to avoid risky investments and preserve capital in the event of a market sell-off – obviously NOT what private equity is all about.

…

As Appelbaum concludes:Why does Moy want to get rid of benchmarks? Probably because he knows that private equity is overpaying for the companies it buys, and thus funds of recent vintage are unlikely to outperform stock market benchmarks. Private equity is paying a 10.1x multiple to acquire a company. For context, at the peak of the last boom, in 2006, the multiple was 9.0x EBITDA. It’s a tough time for PE to invest and perform well – so let’s not measure its performance!

Former banker, now independent private equity researcher Peter Morris, puts this sorry picture in context:

Comparing private equity to the stock market ought to be obvious. But private equity vested interests claim to have suspended the laws of financial gravity. They pretend that returns in private equity are somehow unrelated to the real world – meaning, the stock market. The idea that private equity is different or superior in quality plays a big role in justifying its exorbitant fee structures. Terms like “absolute return” and “alternative investment” are giveaways that this conjuring trick is being played.

What private equity managers actually do is quite simple. They buy companies, often with lots of debt; run them for a few years; then sell them. In between buying and selling the companies, they sometimes make big changes. But the main driver of private equity returns remains a combination of the stock market and financial steroids (meaning the high debt levels).

Once you understand how simple private equity really is, it becomes obvious how to tell if private equity has been a good investment or not. Private equity ought to outperform the stock market, for three reasons. It uses financial steroids (aka lots of debt). It is very illiquid (harder to buy and sell)*. And on top of this, buyout managers say they “create value” by running companies better.

So the key question becomes: Has private equity outperformed the stock market over the long term, net of fees, by a big margin – say, five percentage points a year or more? (Neither the cash multiple nor the

internal rate of return accurately measures this.) If so, then there is a case for saying private equity was a good investment. (There is no excuse, however, for not knowing how much it cost in fees.)If private equity (net) failed to outperform the stock market by a big enough margin, then the

exorbitant fees that investors have paid to private equity managers were a waste of money…The persistent failure of private equity to beat stock market returns by a meaningful margin, even when using leverage, shows that the answer to Morris’m last question is a resounding “no”.

Back to the present post. In the interest of keeping this post to a manageable length, we excised some of the derision of the idea of “absolute returns,” as well as another scathing review by North Carolina’s former chief investment officer Andrew Silton, who said PCA should be fired for giving this advice.

How CalPERS’ Staff Intends to Fool Its Board

Now it is not clear precisely what benchmark/measurement change CalPERS intends to implement, since all they are seeking now is a revision in policy. But notice how they’ve only made brief, in passing references to what finance experts to a person recognize as a monumental and reckless change. And the only finance-literate member of the board is JJ Jelincic. Staff has worked hard at isolating him and in large measure has succeeded. So these in-passing mentions in past board meeting about redoing how private equity returns are to be measured have almost certainly gone over the heads of the rest of the board members. And the staff’s key enabler, PCA, is fully behind the effort to mislead the board.

CalPERS is now seeking to revamp its “Investment policy” language. The memo by PCA supporting it is minimalist; it does not address the elimination of risk from the measurement of private equity returns. In fact, the concluding statement is a Big Lie:

![]()

It is flat out false to claim that eliminating the requirement that CalPERS seek to “maximize risk adjusted rates of return” is not a substantive change.

It’s not hard to see how this will play out. Unless California voters call the Treasurer and Controller and key members of the legislature to make a stink on Friday, the board pretty much guaranteed to rubber stamp this request, as they do for nearly all staff proposals.

Then in a few months, you can expect staff to table the private equity measurement changes. They will tell the board that they follow from the change in strategy language they already approved.

Hence to reject a new benchmarking process* (or more likely, the use of “absolute return,” since that’s what Eliopoulos and Moy have been messaging consistently), the board would need to undo the strategy change they’d approved, which would mean going into open opposition against staff and admitting to past error. Given the history of passivity of this board, what do you think the odds are that they would do that?

So this vote Monday really is the point of no return.

We strongly urge you to call or e-mail the Treasurer, Controller, and your state legislators and give them a big piece of your mind. Remember that a comparatively small number of calls on a seemingly obscure issue, particularly given that the media has yet to take this up in a meaningful way, will get their attention.

Contact details for the elected CalPERS and CalSTRS board members:

Mr. John Chiang

California State Treasurer

Post Office Box 942809

Sacramento, CA 94209-0001

(916) 653-2995Ms. Betty Yee

California State Controller

P.O. Box 942850

Sacramento, California 94250-5872

(916) 445-2636

In addition, if you are a California citizen, please alert your state Assemblyman and Senator, and demand that they look into this serious lapse of governance. You can find you Senate and Assembly representatives here.

Please also contact your local newspaper and television station, as well as the Sacramento Bee. Tell them you think this story is important for all California taxpayers and urge them to take it up. You can find the form for sending a letter to the editor here.

Thanks again for your interest and help.

___

* The New York Times’ Dealbook earlier this week also stated that CalPERS was considering changing its benchmark, and linked to a December 2014 Pension & Investments Online, which suggested that CalPERS might use an absolute benchmark of 9%. But is indefensible, since returns of all asset classes are measured as premia to the risk free rate of similar-maturity (or duration, as appropriate) Treasuries. For instance, historically, the equity risk premium was around 7%; recent studies suggest that even in the post-crisis era, it is still over 6%. So if we assume that the Fed succeeds in raising rates by a point over the next year, you’d expect the yield curve to steepen a bit too. It’s not hard to imagine 5 year Treasury yields rising to 2.5% or higher and 10 year Treasury yields being 3.5% or higher.

You use comparable maturities for risk measurement. Private equity is depicted by CalPERS as a ten year horizon, but it is actually shorter. But even if we charitably use 2.5% for 5 year Treasuries, and assume that the equity risk premium normalizes a bit to 6.5%, you are already at a 9% required return for garden variety stocks. This implies that private equity could actually deliver returns below public equity and still be acceptable.

But bear in mind that that December story may well be superceeded by later thinking, and the statement above are more recent. Another possible preview came in the November private equity workshop, in which CalPERS staff simply compared private equity to CalPERS’ other investments. Again, this is misleading by virtue of the greater risks of private equity (it is a given that a levered investment in a rising market will outperform an unlevered one). And the performance comparison was even more duplicitous by virtue of how CalPERS gamed the numbers and failed to stress that CalPERS’ public equity performance was poor by virtue of having a big foreign currency bet (roughly 50% foreign stock holdings) that had worked out badly in recent years.

CalPERS-Investment-Committee-Dec-15-Item-7a

CalPERS Investment Committee Dec 15 Item 7a

Astonishing that Bayes died before the U.S. was born, and we still have incentive systems based on cranking up false positives.

Or (man muss immer umkehren),

Like The Big Short, the analysis became a perverse guidebook, a means to an end opposite the intent of the equation.

any business school course on vc or pe will say that there are multiple company valuations methodologies, which need to be triangulated. comparing to peers, both publicly traded, and private transactions (with known prices) is a fundamental part of that, indeed, any over or under payment compared to that should be explained.

It’s possible to argue not using say nsdaq as your benchmark, because it is basically all about apple. but it’s againt all the best prctices not to use a benchmark of a basket of similar publicly traded companies.

an unrelted point – Yves, you write tht VaR is beloved of regulators – no, it’s not, you’d update your playbook.

The new FRTB market risk regultions (final version due out in Jan) is firmly ditching VaR (exept for one measure, which is about testing the probability distribution, but not estimating the losses, and where VaR actually makes sort of sense). Expected Shortfall, which is a better messure (or at least not as bad as VaR) is on its way in. Also, frtb includes th idea tht everyone does standedised calculation for comparison purposes. So if you see two similar firms with similat standard calcultion results, but vastly different intrnal model ones, you can strt asking questions. Of course, it’s a big question of whether it will work (I dont think so).

Sorry, I wrote in haste…VaR was definitely used well beyond what should have been its sell-by date because regulators were hooked on it (I’d hear comments from bankers frustrated with regulator fixation on VaR, they were affirmatively not interested in other risk metrics the more savvy banks used).

And separately, as I indicated in ECONNED, the idea of reducing a complex phenomenon like risk for banks in many product in multiple currencies was never a good idea. Using a simple, single metric was always going to lead to big blind spots. …this was true until recently, when the problems with VaR had been known for some time.

***

Actually now that I looked at the post again, I don’t think what I wrote was quite as off-key as you suggest, although I was remiss in not going through the timeline more (perhaps in a footnote) to unpack how long VaR had been used despite getting considerable criticism well before the crisis (famously by Taleb but he was not alone).

agree it was used well past sell date, and that the problems with it were very well documented.

In fact, bis has a paper from 2002 (!!!) that concludes that ‘VaR and ES should not dominate financial risk management’ and ‘The findings imply that wisespread use of VaR for risk management could lead to market instability’

Unfortunately, as is often the case, basel commitee listens to its own researchers way less than to banks it’s supposed to regulate.

ES is also not a great measure, it’s just less bad than VaR. and I’m not even going into how bis tried to incporate liquidity into the new regulation but entirely missing the point (say assuming tht you can liquidate securitiation ‘without moving prices’ over 250 days. No, if you’re JPM whale, you won’t liquidate at any horizon wo moving price. Not to mention that yoou may not have 250 days to liquidate the worst stuff…)

This is just additional “complexity reduction” by Ted…..benchmarks bah who needs them. Staff should be judged by how often they kiss the ring and cover for the embarrassment that is the leader

This strategy reminds me of president Obama’s decision to redefine enemy combatants to mean any military-aged male within a battle zone. Killing civilians presents a problem- no worry- legally define everyone as a legitimate target. Problem solved and the killing goes on.

It seems we have passed the same threshold in the business and financial world. Graft and outright theft have been normalized to such a degree that to protest against such action puts you outside the norms of your society. We have reached the point where corruption is the defining characteristic of our society.

How pensioners and working class people are treated is like watching a car crash in slow motion.

But catch the finesse: Eliopoulos has already introduced a new benchmark, that of “absolute returns,” one not approved by the board or used in CalPERS’ private equity program reviews. And as we pointed out in a later post, PCA’s account manager Mike Moy gave its Consultant Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval to Eliopoulos’ remarks, a strong indicator that PCA and Eliopoulos had crafted this language in advance.

2 points in this passage, 1. the word “absolute” implies certainty where there likely is none, so it’s the

language of propaganda, a “pretty lie”

2. language crafted in advance is not transparent to the board or the public i.e.

“the assoc. of foxes has determined that gates on henhouses are an

unnecessary impediment to reasonable returns and constitute an unfair

competitive practice and unnecessary construction cost and so should be

abandoned”

Previous posts pointed out that Calpers switched from a target 25% return on private equity to a 19% “realized return.” Where does the 19% realized return come from — an industry index, or Calpers’ actual PE results?

Obviously, actual results are what matters. But beyond that, the calculation needs to be reviewed, because it’s more complex than the straightforward formula for public equity volatility. Owing to capital calls and distributions which vary the amount of capital invested, a chained Modified Dietz formula is commonly used to derive volatility from a private equity NAV series.

But it goes farther still. As the European Venture Capital Association drily notes (page 16),

Apply those “statistical unsmoothing techniques,” and the Sharpe ratio of private equity ain’t gonna look that good versus public equity. But Calpers don’t want to go there. Math — close your eyes, and maybe it will go away.

Four comments on Calpers-related posts on four different days have gone “into the ether” of the spam file.

Must be either some keyword or the link that makes WordPress go haywire.

I saw one in moderation, and I did free it, but the others seem to have wound up in Spam. Sorry about that. I’ll go in to find them. You should know, if you don’t already, that we enjoy your comments.

Most sincere gratulations for a fantastic piece of work altogether. I don´t live in the States and have no pension to expect there but reading how you exposed Calpers post after post is truly fascinating. How utterly cynically some play with other people´s money. I just wonder: is it corruption or just stupidity that explains Calpers behaviour?

On the “stupidity v. corruption, my take is it has as lot more to do with capture and fear of the general partners than what normally passes for corruption. For instance, there is pretty much no revolving door between private equity and public pension funds.

But you do have:

1. Staff at places like CalPERS who fear incorrectly that a general partner could get them fired (people in industry whose judgment I trust tell me that belief is common and very much misplaced, since a GP would lose more than he would gain in that effort and they know that). More important, however, staff believe that a GP could help them in getting a next job (introductions, putting in a good word).

2. GPs probably could get a consultant fired (“They are wasting our time, they are asking questions no one else asks, they don’t seem like they know what they are doing”). The law firms similarly make far more money working for PE firms than folks like CalPERS, so they will not get aggressive on behalf of limited partners. That means the advisors supposedly hired to give CalPERS independent advice have a very big vested interest in not raising anything more than minor issues re PE.

3. GPs are big political donors, so elected officials have incentives to curry favor with them

4. Bizarrely, CalPERS seems utterly unwilling to consider alternatives to private equity that have delivered similar returns. They cook the number so as to rule them out. I don’t have the sense they’ve ever given them a good-faith look.

5. CalPERS thinks it has to be in PE as a result of 4: it has to be in some higher-risk strategies to meet its return targets, and it has ruled out alternatives to PE.

So you have 1-5 operating in combination with that great saying by Upton Sinclair: “It is very difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

On “capture & fear” v.s. “corruption”–I see these as related. They describe actions and situations that twist or distort our inner “straightness”, that lead us to diverge from a standard of “right action” according to our inner compass. We do something we don’t really want to do, because of the reward.

Doing things to get approval of our peers, but not getting cash in an envelope, is nonetheless a corruption of our inner being. I go back to a comment I made on another thread–it’s a form of prostitution. Some cases are more disgusting and objectionable and overt than in other. (And CalPERS is disgusting because of the size of the financial impact due to the many billions at stake, and because the victims include those without a voice in the matter–pension beneficiaries who both deserve and need to get back what they paid in.)

Many of us “sell” ourselves often, in subtle or overt different ways. Some of these ways are consistent with social norms, i.e. a consensus veniality (e.g., not declaring certain things on tax forms might be “the done thing” in certain circles, or handling a social interaction in a certain way to get someone else’s approval even though it is discordant with what we sense is right).

Being true to ourselves is a task that never ceases.

CalPERS magnifies the crudeness and injustice of the societal injuries when public fiduciaries lose their way and sell themselves to please the system.

Pardon my ignorance, but I’m trying to get up to speed on some of this. The proposed policy change doesn’t only eliminate how PE risk must be accounted for. On Page 2, the change seems to remove or modify the requirement that staff try negotiate ways to create an “alignment of interests” (an “alignment” that Don Ochoa says is never going to be possible with publicly-traded PE GP’s).

STRIKEOUTS in original don’t show in SmartPhone cut-and-paste…

This is just INSANE. The only reasonable conclusion is that there is more self-dealing by staff.

I wonder what the FBI might still be investigating in relation to the Buenrostro affair.

Looks like the CalPERS staff has decided to double-down. Thanks to Yves’ posts there is a record of their action and a record that eliminates any “we didn’t know, nobody could foresee” defense they might use in future.

Maybe other pension funds will learn something useful. Bull-headed doubling-down does not count as useful.

Bingo, i think thats why the board is being so harsh on Mr Jelncic, amidst an ongoing FBI investigation he keeps drawing unwanted attention. For Ann Stausboll and im sure a lot of other senior execs its completelt CYA mode, fighting for their political “careers” and Jelincic is the fly in the ointment

Speaking of risk, i recall the board meeting where the Cio Ted diaplayed his ignorance (and flop sweat) and repeatedly referred to VaR as “variance at risk”……… and that is our leader? The CIO of the largest pension in the US?

We also had Christine Gogan, who is a senior officer in PE at CalPERS and appears to be official designee to talk to the press on more technical matters, in a recent board meeting refer to the major accounting firms as “the big three”.

I was able to bring this issue up with California State Controller Betty Yee on Thursday at the holiday luncheon (at Steven’s Steak House near Downtown Los Angeles) for the Professional Engineers in California Government (PECG, union for Caltrans engineers). She was gracious in answering my question. She said that she was also concerned. She said that lack of transparency with hedge funds is common to all states. She said that she is working with the SEC to improve the situation. I also spoke to the leadership of PEGC and suggested that we invite J. J. Jelincic to one of our quarterly luncheons.

*Sigh*. As we wrote, her remark is tantamount to asking the SEC to do her work. We discussed that longer form here:

State Officials Try to Hide Their Private Equity Oversight Failures by Asking the SEC to Exceed Its Authority

And it was Chiang’s name who was on that letter, not hers. She’s at best riding his coattails and at worst trying to take credit for his outreach (as in rely on public inattentiveness as to who was behind that initiative). And Chiang has done more than “be concerned,” he’s proposed serious legislation in California re private equity transparency.

Needless to say, really disappointing.

But it would be great to have Jelincic speak. I hope the PECG is receptive.