Yves here. This post is the author’s summary of a new working paper Lowering the Marginal Corporate Tax Rate: Why the Debate?, which was a co-winner of the 2015 Amartya Sen Prize Competition given by the Global Justice Program at Yale. It puts another nail in the coffin to the idea that lowering corporate tax rates will boost growth.

By Nikolay Anguelov of the Department of Public Policy, University of Massachusetts, Dartmouth. Originally published at Tax Justice Network

Internationally, countries ‘compete’ to attract foreign direct investment (FDI) from multinationals. Despite the increasing evidence of the negative consequences of tax competition, governments continue to base their economic development strategies on it.

The two policy outcomes that are measured when considering tax competition between states are FDI and economic growth.

The assumption has long been that lower corporate taxes lead to increases in FDI, resulting in “capital formation” that generates economic growth. This key assumption is politically attractive because it suggests that the foreign firms link to local production networks and in addition to creating jobs, also provide knowledge transfers that increase the productivity of their local partners.

Site selection firms broker recruitment deals between local governments and foreign investors, gaming the process for their own profit, which they earn based on winning the best incentive package for the global investor. Governments agree to lower and/or eliminate recurrent businesses costs, which are utility and tax rates. A winning bid technically translates into forgone public revenue sources. States lower tax rates, in what many call a ‘race to the bottom.’

Those Falling Tax Rates . . .

The key questions are: what happens over time in this downward-spiralling cycle? And are the benefits of attracting multinational corporations (MNCs) worth the costs of foregone public revenue?

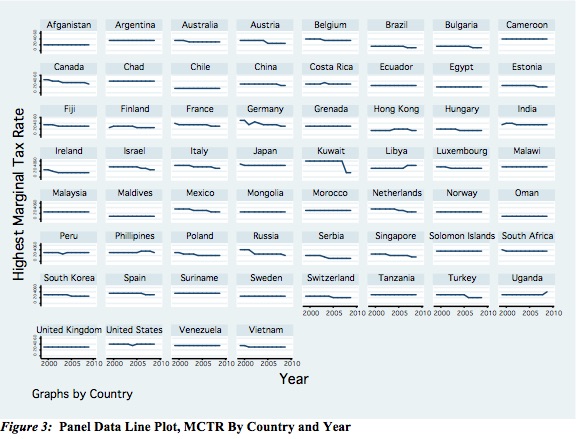

It is this dynamic that I have tracked in my paper, “Lowering the Marginal Corporate Tax Rate: Why the Debate?” It offers a 60-nation analysis of the economic impact of inter-state tax competition over time.

The paper tracks the incentives behind such behaviour in terms of the race-to-the-bottom competition among nations, with a focus on the developing world and its dependence on foreign investment. The paper is an extension of my work on national competitiveness policies published in my 2014 book Policy and Political Theory in Trade Practice: Multinational Corporations and Global Governments (New York: Palgrave Macmillan.) The book tracks how tax competition hurts individual states in the United States. The paper builds on the book’s models, extends the query internationally, and finds that nations that engaged in aggressive tax competition experienced decreased economic growth over time.

The analysis focuses on the main economic indicators that respond to tax incentives, such as MNC mergers and acquisitions, FDI flows, MNC incorporation, internationalization, and global market power.

Looking at data from 1999 to 2009, with the explanation that the first decade of the 2000s ushered unprecedented levels of international economic integration as a result of trade liberalization and globalization policies championed in the 1990s, the study shows that reduced corporate tax rates can increase FDI but over time that increase leads to a negative impact on GDP.

Among the reasons for this paradox is the elusive concept of “capital formation”: a shorthand for genuine wealth creation.

FDI may not create it because today a significant portion of that FDI may be in financial instruments for debt-reducing, tax-deductible write offs, as opposed to operational FDI that generates real economic activity.

This finding relates to the changing nature and fluidity of FDI. Most of it today is not in operational assets, but financial instruments, including debt – so increasing aggregate FDI can actually lead to a loss of tax revenue, if debt and operational assets are treated as tax deductible liabilities. It is this point that politicians miss because of a legacy of economic theory that teaches them that capital and capital formation go hand in hand, and they simply assume that this is the case.

– go hand in hand

go from (insert name here)’s hand into (insert name here)’s hand

.

How much lower then zero can they go?

2/3rds of all U.S. corporations pay zero in federal taxes according to a Government Accountability Office study.

Negative numbers. Child worker support, French wine and food stamps, penthouse housing projects, alimony for fired CEOs, public-private corporate jets, military assistance for comparative advantage marketing strategies, hooker development research funding, obedience school training for congressmen, legal defense assistance…stuff like that.

Quite a bit actually. We subsidize, give tax credits, and sometimes pay them directly just to set up shop in our communities…

Yes, in a related vein wonder if anyone has done a study of state and local tax forbearances stemming from the race to the bottom between states to determine how much of those indirect subsidies have effectively been used for corporate dividend payouts and corporate stock repurchases that benefit CEO’s through stock option compensation; rather than plant upgrades, R&D and other productive employment.

Here is one that looks at the dynamics at the local and state level on business location decisions. There was going to be a follow up working paper at the Center for American Progress or the Center for Budget and Policy Priorities, but I am not sure if that has happened yet.

This also does NOT address what firms and corporations do after they receive the breaks.

From the Economic Policy Institute in Washington DC:

http://www.epi.org/publication/books_rethinking_growth/

Whut craazyboy and Joe, above, said… it’s not just that most of the Bigs don’t pay any taxes at all… they are being highly compensated – mostly by you ‘n me in the 99% – to do bidness at all. They get all kinds of “incentives” from the US taxpayer. It’s a real scam. Hope you enjoy being ripped off. /s

Someone still needs to explain how a lower marginal tax rate which increases the after-tax cost of labor leads to job creation.

I have a friend, and of course, everything is Obama’s fault, and those damn high taxing dems.

(never mind both parties want to lower taxes for their bribers…uh, I mean constituents, as well as subsidize their bribers – – OH O! there I go again – – I mean subsidize their constituents….it just depends who their particular bribers….OH I am incorrigible…..that is, constituents are…

And of course, I get told about how when I retired I shouldn’t live in high tax CA.

So than I ask him why he lives in NJ with its higher income AND property taxes…..well, OF COURSE, its the only place he can get a job. A few Socratic questions, and it turns out its the only place he can get A HIGH PAYING job – apparently, he is unwilling to be a 7-11 clerk in Mississippi. uh huh….but I thought LOW TAXES were the most important thing…

So I note that I would be paying much, much lower taxes if I lived in Mississippi. Turns out, he doesn’t want to visit me if I live in Mississippi, as apparently their vineyards are low quality….

It is of course an aspect of illogical humans that it should be perfectly consistent that a place with high prices will have high taxes. And that despite the high prices and high taxes, people flock to NY, and their aren’t that many flocking to Mississippi*…

*I note that when I visited New Orleans several years ago, the riverboat casinos on the Mississippi coast and river provided a much higher degree of cosmopolitan amenities than I would have ever dreamed. I really was amazed at the number of Mexican and Sushi bars in the interior as well. At some point, low prices will attract people – at some point, maybe Mississippi will become the new Florida.