Yves here. There are so many fracture points in the financial system that are now under stress that it is hard to keep on top of them all. One has been Italian banks. In 2011, Unicredit, which ironically is the successor by acquisition to Creditanstalt, the Austrian banks whose failure in 1931 triggered the slide into the Great Depression nadir of 1932-1933, was rated the second worst bank in the awfully permissive European stress tests. It had gone on a buying spree, picking up often-weak institutions at elevated pre-crisis prices. Even after multiple capital raisings and years of clean-ups, UniCredit now has non-performing loans that stand at 20% of its loan and receivables book.

From a Financial Times article earlier this month:

“The banking sector is a crucial problem of Italy,” says Luigi Zingales, professor of entrepreneurship and finance at the University of Chicago Booth School of Business. “When there is low tide you see who is swimming naked. And we have a low tide and all the problems are coming to the surface.”

By Silvia Merler, an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel whose specialties include international macro and financial economics, central banking and EU institutions and policy making. Previously, she worked as Economic Analyst in DG Economic and Financial Affairs of the European Commission (ECFIN). Originally published at Bruegel

Italian banks have recently come under market pressure, as investors seemed to have grown worried about the sector. This triggered a speed-up in the discussion between the Italian government and the European Commission about the creation of a “bad-bank”, on which a decision is reportedly due this week.

Taking a step back, it is important to understand what could be behind the sudden change in market sentiment. Borrowing a literary expression, this is to some extent the chronicle of a death foretold. Italian banks have been very resilient to the first wave of financial crisis in 2008, due to the low exposure of Italian banks to US products and to the fact that there was no housing bubble that burst (contrary to what happened e.g. in Spain). But when the financial crisis turned into a euro sovereign banking crisis, things started to deteriorate for Italian banks, and they have really never improved much since then.

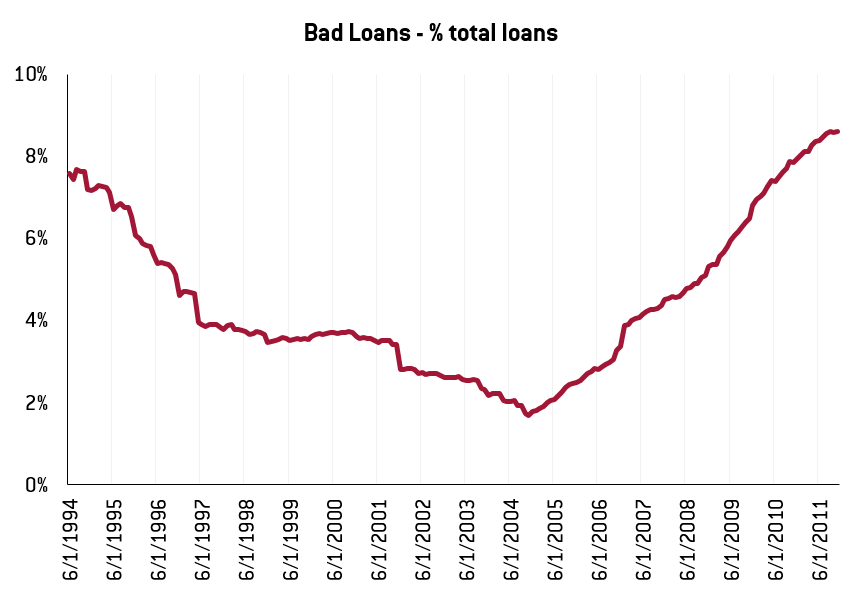

Figure 1

Source: own calculations based on data from Bank of Italy

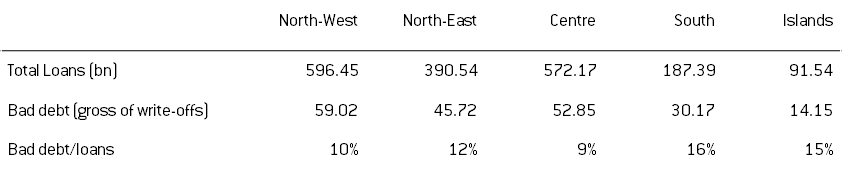

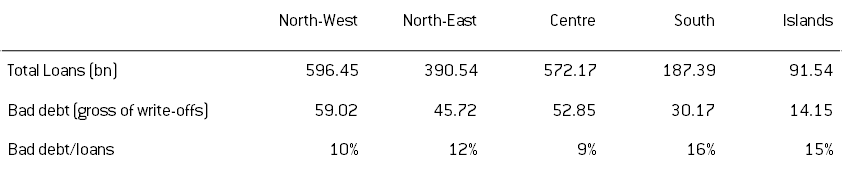

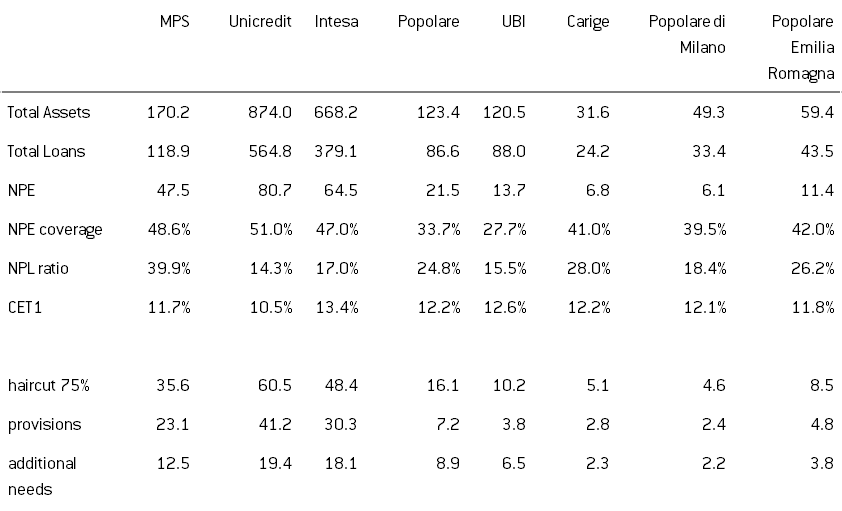

As the economic situation worsened, bad loans accumulated on banks’ balance sheet, making it increasingly difficult for them to lend to the private sector and support the economic recovery. Bad loans have been growing constantly ever since 2008, and reached 200bn euro in September 2015. This is roughly equivalent to 9% of total loans, a level that was unseen since the late Nineties. About 71% of the total bad debts is made of loans to non-financial corporations, whereas 27% is constituted by loans to households, and the ratios are higher in the Southern and Islands regions – where the economic situation is worse – than in the North (see Table 1). At the bank level, the situation is mixed (Table 2). Non-performing Loans ratios range from about 14% for Unicredit to as much as 39.9% for Monte dei Paschi and coverage ratios also vary considerably across the individual institutions.

Table 1 – Bad debt by geographical area

Source: own calculations based on data from Bank of Italy

The existence of sizable and increasing bad loans in the Italian banking sector has been known for quite a long time (see e.g. here and here). What acted on market sentiment is probably a worry about how this could play out in the future, given that the new regime for bank recovery and resolution (the BRRD) has now entered into force.

The recent episodes of “creative” resolutions of four Italian banks have in fact highlighted a potentially very serious problem, i.e. that over the past years some Italian banks had been placing their subordinated debt with retail customers who were unaware of the true risk associated with these products.

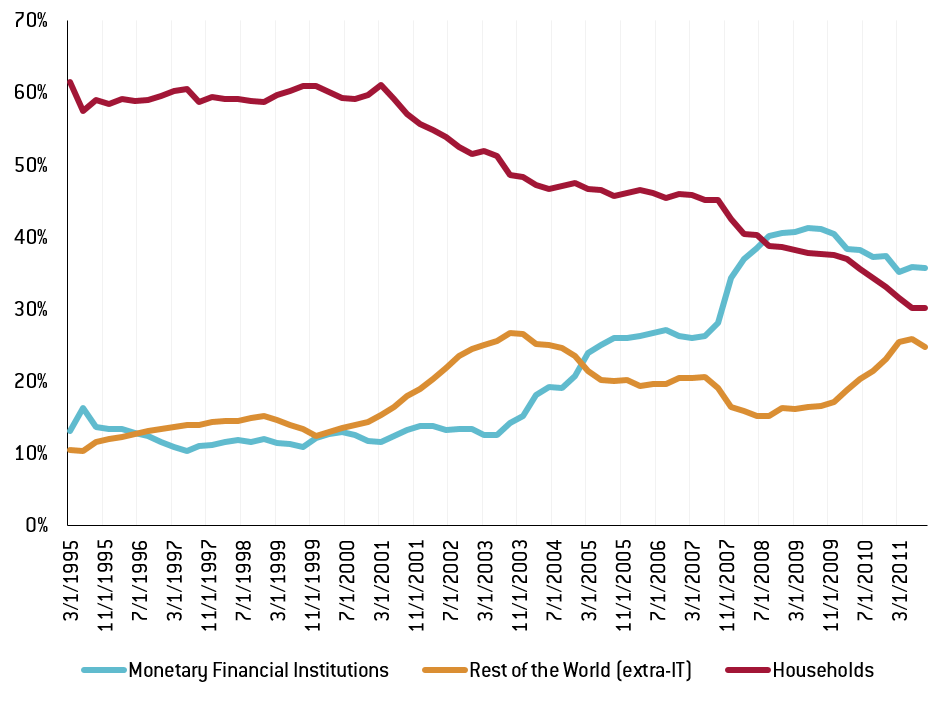

Figure 2 shows that as of September 2015, Italian households were holding about 30% of the total bonds issued by Italian banks, slightly less than the 35% that was held by other Italian banks. The households’ share of total bank bonds used to be much higher (around 60%) until the mid-2000s. It declined to about 45% between 2005 and 2007, mostly substituted by increased foreign holdings, and it started to to decrease again in 2011, substituted this time by increased holdings of other Italian banks.

Figure 2 – holdings of Italian banks’ bonds, by sector (% total)

Source: own calculations based on data from Bank of Italy

The entry into force of the BRRD makes this a thorn in the side of the Italian government. BRRD aims at reducing the cost of bank rescues for taxpayers, which would be especially problematic for states – like Italy – that have high public debt. But in order to do so, BRRD requires sizable bail-in of bondholders, which in the case of Italy can likely retail holders with limited awareness of the risk. The potential for political backlash is obviously large, and “creative” solutions like those implemented this fall to protect senior bondholders will hardly be possible under BRRD. Even if they were possible, it would be very difficult to engineer them, because of their cost. The operation that was carried out to resolve four banks in November without haircutting senior bondholders required the three biggest Italian banks to advance the money that were not in the resolution fund. And these were only 4 very tiny banks, making up for around 1% of Italian deposits in total.

These worries, and the resulting market stress, speeded up the talks between the Italian government and the European Commission about the creation of a bad bank. This could be a potentially important step to finally clean the Italian banks balance sheet, but it is probably not going to be miraculous and it is certainly not going to be as easy as it would have been in the past. According to Reuters, the plan that is being discussed aims at reducing the balance sheet impact of the necessary writedown by having the bad loans sold to special vehicles, which would issue bonds to fund the purchase. To make the bonds appealing and cheaper to issue, Italy would offer a state guarantee on them, with the underlying idea that the easier it is for the SPV to finance the purchase and the better the terms on which it can buy the loans from the banks, thus limiting the balance sheet impact.

But the implementation of this public-private scheme could be much more difficult today under the new regulatory framework than it was at the time when Spain and Ireland cleaned up their banking sectors. The point of contention is the the price at which the banks will be able to offload their bad loans to the vehicle. If this price is too low, than the writedown could have a sizable impact on banks’ balance sheet and it would not reassure the markets. Reuters reports that the selling price of the bad loans to the SPV could be between 20 and 30 percent. If we pick the average (25 percent), a very simple back of the envelope calculation suggest the existence of additional provision needs for the sector (see table 2). On the other hand, if the government guarantee were such that the selling price resulted too high compared to the market value of the loans, then the operation would be considered state aid.

Table 2 – selected indicators at individual bank level

Sources: banks’ reports

Last year, just after the release of the ECB stress test results, I wrote about some long-term structural issues – such as the low profitability of the Italian sector compared to e.g. the Spanish one, or the complex and opaque governance system. While having been know for a long time, these problem were at that time lying quietly below the surface waiting for their moment of recognition.

The final wake up call might have finally come on the 1st January 2016, when the Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD) officially entered into force. Based on the management of recent resolution episodes, investors have probably realised that the Italian government will have troubles managing a change that could have potentially relevant social consequences of which the country had little awareness until a couple of months ago. Facing the long-lived issues in the Italian banking sector is now urgent, but Italy might have waited too long for it not to be painful.

The heat is on or the auditors are on the prowl……

The current “extend and pretend” exercise, otherwise known as “eat your cake and keep it” attempt to avoid unpleasant outcomes, depends, IMHO – on the willingness of the auditors (PWC in case of Unicredit?) – to attach a value to these pesky non-performing loans – and sign an unqualified audit opinion by roughly end of January.

As described above, one way or the other, losses on these loans, where repayment is shaky at best, need to be taken – somewhere – an unpleasant event too close to reality.

(please note, Italian banks are still subject to IAS 39, if applied as it has been for decades now, does NOT require the accountants to recognise “future losses” i.e. recognise the losses arsing from payment misses between now and the end of the contract– unless certain criteria are already given in the present – kindly ignoring that reality is not so clear cut – and the replacement “bucket approach” – not yet obligatory – would allow a similar “extend and pretend”, but with much more obfuscation to hide the fact)

If you impair these loans “on” balance sheet, the bank will look bad, any may even be in need of a bailout, in which case the new regime of “bail in” would require senior bondholders to bear losses – which will make these instruments much less attractive and may cause a knock-on effect up to a bank run.

Especially, and here I would appreciate some insider knowledge, to which extent these “senior bonds” already carry a “guarantee of the Italian State” to make them eligible as ECB collateral – i.e. to which the Italian treasury would need to open her coffers to make good on these guarantees – to the ECB?

If you transfer these loans to a “bad bank”

– a) at “fair value”, i.e. the expected future cash-flows – the loss will “crystallise” on the bank balance sheet, as per above

– b) at some “mark to make believe” value to spare the bank and the reputation of the Italian banking sector – the bond holders of the SPV will have to bear the losses, unless they get a guarantee – from the Italian State, were arcane accounting requirements would prevent the immediate recognition of the “loss, aka expense” – but would be considered “state aid” – and would break EU rules, probably the last thing on anybody’s mind, but still.

As per above, the whole thing is time critical, and thus another thing – which I do not know how to integrate into the picture, which is certainly incomplete. Upon publication of an article by German Finance Minister, W. Schaueble, in the FAZ this week – were he kind of gave “green light” for the next step of the banking union, i.e. the inclusion of the well-heeled German deposit guarantee scheme into the “waterfall” of loss bearing “assets” – Italian bank shares rose quite considerably.

Anybody any idea why?

The main problem with italian banks is that they do what a commercial bank is supposed to do, they lend money to businesses and households.

So they suffer a lot from the state of the real economy and they benefit from the ECB policies less than other EU banks which behaved worse and dealt with riskier stuff.

Let’s not forget the massive bailouts done by other EU countries throughout the past years and until a few months ago. The same kind of help which is now forbidden to Italy even for a fraction of the amount.

And shall we recall that as Italy was recovering from the GFC in 2011 they replaced Berlusconi with Monti who increased austerity to a level that sent us back into recession? And that was not a mistake, it was done on purpose to destroy internal demand, in order to preserve the Euro, which of course sent the NPLs sky high.

> The recent episodes of “creative” resolutions of four Italian banks have in fact highlighted a potentially very serious problem, i.e. that over the past years some Italian banks had been placing their subordinated debt with retail customers who were unaware of the true risk associated with these products.

This was a consequence of the bail-in scheme. They mandated the banks to recapitalize and the obvious way was to issue subordinated debt. The EU knew it had created a conflict of interest between the banks and their customers.

> The recent episodes of “creative” resolutions of four Italian banks have in fact highlighted a potentially very serious problem

The “creative” resolutions were a partial application of the EU bail-in. It was applied before the turn of the year so that it would be milder. Otherwise things would have been much worse.

The only way out of this mess is to leave the Euro. That would allow the economy to recover, solving the root cause of the NPLs, and would restore the country capability to bail out the banks without destroying savings.

I don’t disagree if Italians want to leave the euro they helped kick off 60 years ago, then absolutely, leave. But I’m curious, you claim that doing so would get Italy out of the mess. In your view, how does reintroducing a national currency unit affect debt denominated in euros?

It sounds like what you are actually proposing is debt repudiation, which is very different from withdrawing from EMU.

The lex monetae applies to all credit/debits under national jurisdiction no matter the currency they are denominated in. Almost all italian public debt, and most of the private debt as well, is under national jurisdiction. So all of this would be redenominated to new liras on change over.

This implies debt devaluation which is not repudiation. For example UK in 2008 devalued sharply to absorb the financial shock, so did its foreign debt. Nobody spoke of default/repudiation because of that.

And then of course issuing debt in your own currency is a very different thing than issuing debt in a foreign currency (the euro).

However what I meant with my previous comment was that once you regain monetary sovereignity, and you use it ignoring all neoliberal nonsense, you can bailout any bank you think is appropriate without taxing anyone. Again, like the UK which bailed-out, and in some cases nationalized, for the equivalent of 1000 billion euros.

I also meant that, the euro, is a rigged FX market where inflation and competitiveness differentials are masked and do not result into appreciation/devaluations as they should. Which means that some countries in the eurozone can benefit from a permanent real devaluation while all their EZ trade partners go bust because of that. This is what has been destroying the italian economy since 1996 when we locked the exchange rate and then we entered the euro.

The purpose of austerity in the EZ is to destroy internal demand and income so as to curb imports in the countries where the currency is overvalued in real terms and keep foreign debt under control.

So, the euro is the cause of the NPLs and is also what prevents you from handling them properly.

So you propose devaluing the new lira against the euro. Again, I don’t have a problem with that. Let’s just be honest. That reduces the living standards of people who used to have claims on ‘euros’ and now have claims on ‘liras’ because the government forced people to accept new liras at 1:1 for old euros but simultaneously will not give you euros at 1:1 for the new liras. It is the same macroeconomic thing as repudiation. It’s just semantics. The same outcome can be accomplished within EMU, too, for example by imposing a new tax or cutting payments to government workers and suppliers. Those are all policy choices the Italian government possesses regardless of the national currency it uses. Italy could adopt the USD and it would still have those same basic choices of how to distribute the losses from financialized gambling.

The action going on here is related to decreasing the real value of the debt, not changing the currency unit.

As far as this:

Sure, you can do that. That’s what we’ve been doing in the western world for two decades now. How is that working out?

> So you propose devaluing the new lira against the euro.

Not exactly. I propose to let the currency float to its correct value. I believe it will devalue because its value is wrong, now.

> Let’s just be honest. That reduces the living standards of people who used to have claims on ‘euros’ and now have claims on ‘liras’ …

To be fully honest, the living standards of italians depend on the internal value of the currency, that is on inflation, and income. The passthrough of devaluation to inflation is typically very low in Italy.

The living standards of italians are being reduced by the euro. Wages are cut, people have lost and are loosing jobs, people commit suicide.

> It is the same macroeconomic thing as repudiation.

So every time some currency appreciates and correspondingly some other devalues, that is, every day, you see some repudiation happening even though the currency is properly valued.

Italy shouldn’t leave the euro cause it would repudiate. We should stay in so that all other EZ countries which are undervalued can keep reputiading.

The eurozone as a whole is repudiating as the ECB is keeping the euro artificially low to keep the eurozone alive, not well but alive.

> The same outcome can be accomplished within EMU, too, for example by imposing a new tax or cutting payments to government workers and suppliers.

Not at all. This destroys income and demand, competitiveness, production capability and creates a downward spiral.

> Those are all policy choices the Italian government possesses regardless of the national currency it uses.

Yes we would still have all the bad policy choices. The problem is with the euro we lack the good ones.

> Italy could adopt the USD and it would still have those same basic choices of how to distribute the losses from financialized gambling.

Right. Because the USD is a foreign currency for us. The matter is different with a sovereign currency.

> Sure, you can do that. That’s what we’ve been doing in the western world for two decades now. How is that working out?

The bail-in though is far worse.

I’m not saying I’m happy to save banks which misbehaved and gambled. Commercial banks and speculation ones should be separated.

Supervisor institutions should monitor their behavior and held liable when they let banks misbehave.

But once you get to the point where a commercial bank is in trouble you cannot make ordinary people pay with their savings for someone else mistakes.

I would encourage you to think through the internal logic of the various claims you are making.

Related topic–the Final Report of the Banking Inquiry (Ireland) has just come out.

A news story about its findings (which were limited by time constraints, political constraints including an upcoming parliamentary election, and Irish label laws) is here.

There are several other articles, including identifying problems with bank & regulatory executives (not named in the report, AFAIK) and failure to identify risk.

Much is made of two ECB threats to withdraw funding to Irish banks, in 2010 and 2011. (Similar tactic used on Greece last year to force it to capitulate?)

That’s an interesting framing. Maybe there are subtleties in American English and the passive voice that play differently in Europe? Maybe the phrase “economic recovery” doesn’t have the same comical ring to it across the pond? At any rate, bad loans are a causal force making the situation worse, not some innocent victim of external economic forces. At our contemporary scale of financialization, moar is a cause of our economic malaise, not a solution to it.

What a terrible idea. Are we honestly back to bail us out or we’ll shoot your dog type arguments?

The State to guarantee bankers’ loans and profits (incomes).

But the State will not guarantee people’s incomes.

And by bailing out indirectly (via SPV and govt. guaranteed bond issue) you not only obfuscate the fact that state aid is being delivered to the banks but generate a whole bunch of extra fees for the intermediaries. Win-win!

Contrast the cautiously-optimistic tone of this piece with Don Quijones over at Wolf Street, who more honestly puts the crucial “who pays?” issue right into his title: Who Gets to Pay for the Italian Banking Crisis?

o Quijones notes “[Italian banks’] non-performing loans have soared to more than 350 billion euros, a fourfold increase since the end of 2008. At 18%, Italy’s ratio of nonperforming loans is more than four times the European average…”

o Ms. Merler optimistically describes the bad-bank idea as a “potentially important step to finally clean the Italian banks balance sheet”, whereas Quijones is more blunt w.r.to the twin promises of finality and cleansing, both of which appear to embody the “raging bullshit” name of his blog: “As experience in Spain and Portugal has shown, setting up a bad bank serves as little more than an accounting gimmick to cloak reality. As WOLF STREET reported last year, Spain’s bad bank, Sareb, is hemorrhaging funds at a frightening rate while taxpayers are likely to be on the hook for roughly half of its decomposing assets for at least another ten years to come.”