It’s ugly out there.

The proximate cause of this week’s market wobbles was a sharp selloff in bank stocks in Europe on Monday. That appeared to be triggered by the recognition that energy related dud loans could imposes losses of an additional $100 billion on already wobbly banks. And that’s before you get to the fact that many banks already had corporate loans they had not written down sufficiently and those books can only be getting worse given low growth and borderline deflation in Europe. And on top of that, European banks lent to other commodities players, not just energy concerns, and many were active in lending in emerging markets (Deutsche Bank, the most undercapitalized of the megabanks, is almost certainly exposed to all these trades, and its stock has been swooning accordingly).

But as bad as this bad loan story is, and the foregoing is already pretty ugly, the underlying structural and regulatory picture is is vastly worse. Central banks have painted the financial system in such a tight corner that it’s not clear how they get them out. And even if there were no big dud loan overhang, banks would bleed to death under current circumstances.

First, the current low interest rate environment has been squeezing banks’ bread and butter source of earnings, like risk-free income on float and other sources of net interest margin (“NIM”), as Izabella Kaminska has reported at FT Alphaville. From a post last week:

Without NIM, there is no banking. Negative rates eat NIM. They also encourage all sorts of bad banking practices.

The Fed’s rate hike was supposed to help the banks with the NIM problem. It was even said that the rate hike would destroy the NIM problem, not make it stronger. Indeed, it was supposed to bring balance to interest rates, not leave them in negativity, and flat.

Low interest rates have already been slowly strangling long-term investors like life insurers and pension funds, although the long-dated nature of their liabilities means they can lumber along in an unhealthy state for far longer than banks can when their usually pretty thin equity capital starts looking too thin.

And John Authers has a very important, and very alarmed article at the Financial Times this AM on how the flattening yield curves are also whacking banks. Key sections of his article:

Markets do not believe that the Federal Reserve will follow through with higher rates, and instead believe that the tightening that has already happened will intensify deflationary pressures. Hence inflation break-evens — the implicit forecast for inflation over the next decade, derived from the bond market — have fallen to their lowest since 2009.

Most critically, this means that long bond yields have fallen far more sharply than shorter-term interest rates (a “flattening yield curve” in the financial argot). Yields on 10-year treasuries now exceed yields on 2-year bonds by less than at any point during the crisis. The yield curve is at its flattest in almost nine years.

This is dreadful news for banks, which make their money by lending money at high interest rates over the longer term while borrowing it at lower rates in the short term. A steep yield curve was a recipe for boosting their profits and allowing them steadily to rebuild their capital. Now, their profit outlook has sharply worsened.

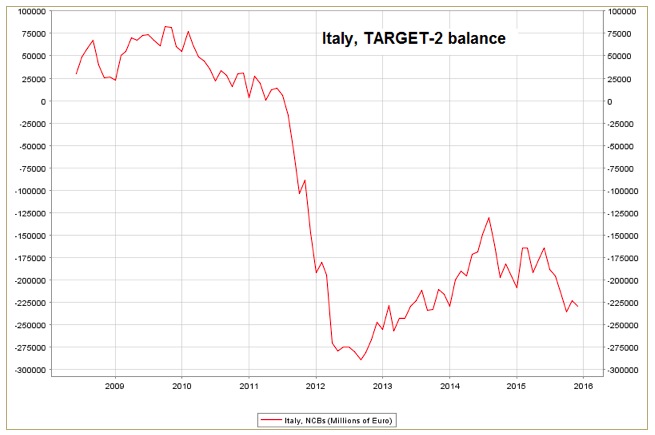

Second, certain major banking markets are looking precarious. There is already a slow-motion bank run underway in Italy as Target2 balances are rising:

Readers may recall that Target2 loans are supposed to be short-term loans from the ECB to healthy banks just for short-term liquidity needs. But as we saw with Greece, they too often serve as a way for the ECB to prop up sick banks and banking systems. But the ECB still requires decent-looking collateral for these loans. Pater Tenebrarum describes how this collateral is being manufactured for Italian banks:

As an example here is how Italian banks and the Italian government are helping each other in pretending that they are more solvent than they really are: the banks buy government properties (everything from office buildings to military barracks) from the government, and pay for them with government bonds. The government then leases the buildings back from the banks, and the banks turn the properties into asset backed securities. The Italian government then slaps a “guarantee” on these securities, which makes them eligible for repo with the ECB. The banks then repo these ABS with the ECB and take the proceeds to buy more Italian government bonds – and back to step one. Simply put, this is a Ponzi scheme of gargantuan proportions.

Third, even though, as we saw with Greece, the ECB can keep this going for an impressively long time, there has been a change in the rules of the game since the extend and pretend show in Greece last year. The Eurozone has created the worst of all possible worlds, unified bank regulation with effectively no approach to rescue banks, and only nation-level deposit insurance, which in many countires is inadequate even on the nominally covered first €100,000 of deposits. And after that, depositors are subject to bail-ins. Mind you, there are some bank depositors who simply can’t avoid keeping more than €100,000 in a particular bank, most important small and medium-sized businesses, which are the core of Italy’s economy (there is far less economic activity concentrated in big companies than in the US). So any Italian businessman with an operating brain cell will be moving his business to a solvent-looking non-Italian bank.

Here are some of the ugly details of this Rube Goldberg version of a regulatory regime, from a fine article by Thomas Fazi:

On 1 January 2016 the EU’s banking union – an EU-level banking supervision and resolution system – officially came into force….In its original intention, the banking union was supposed to ‘break the vicious circle between banks and sovereigns’ by mutualising the fiscal costs of bank resolution….

In the course of constructing the banking union, however, something remarkable happened: ‘the centralization of supervision was carried out decisively; but in the meantime its actual premise (that is, the centralization of the fiscal backstop for bank resolution) was all but abandoned’, Christos Hadjiemmanuil writes. Within a year, Germany and its allies had obtained:

- the exclusion from the banking union of any common deposit insurance scheme;

- the retention of an effective national veto over the use of common financial resources;

- the likely exclusion of so-called ‘legacy assets’ – that is, debts incurred prior to the effective establishment of the banking union – from any recapitalisation scheme, on the basis that this would amount to an ex post facto mutualisation of the costs from past national supervisory failures (though the issue remains open);

- critically, a very strict and inflexible burden-sharing hierarchy aimed at ensuring that (i) the use of public funds in bank resolution would be avoided under all but the most pressing circumstances, and even then kept to a minimum, through a strict bail-in approach; and that (ii) the primary fiscal responsibility for resolution would remain at the national level, with the mutualised fiscal backstop serving as an absolutely last resort.

Bailing In For Distressed Banks

In short, when a bank runs into trouble, existing stakeholders – shareholders, junior creditors and, depending on the circumstances, even senior creditors and depositors with deposits in excess of the guaranteed amount of €100,000 – are required to contribute to the absorption of losses and recapitalisation of the bank through a write-down of their equity and debt claims and/or the conversion of debt claims into equity.

Only then, if the contributions of private parties are not enough – and under very strict conditions – can the Single Resolution Mechanism’s (SRM) Single Resolution Fund (SRF) be called into action. Notwithstanding the banking union’s problematic burden-sharing cascade (see below), the SRF presents numerous problems in itself. The fund is based on, or augmented by, contributions from the financial sector itself, to be built up gradually over a period of eight years, starting from 1 January 2016. The target level for the SRF’s pre-funded financial means has been set at no less than 1 per cent of the deposit-guarantee-covered deposits of all banks authorised in the banking union, amounting to around €55 billion. Unless all unsecured, non-preferred liabilities have been written down in full – an extreme measure that would in itself have serious spillover effects – the SRF’s intervention will be capped at 5 per cent of total liabilities. This means that, in the event of a serious banking crisis, the SRF’s resources are unlikely to be sufficient (especially during the fund’s transitional period).

You can see I’ve stopped to spare you further pain, since this is sufficient to give you the drift of the gist.

And while I’ve mentioned one obvious group in the cross-hairs in the event of a bank bail-in, there’s another that Tenebrarum points out: retail investors who were persuaded to buy subordinated bank debt as an alternative to deposits, telling customers (falsely) that they were safe and provided a higher yield:

Many of said creditors in Italy were small savers who were talked into buying subordinated bank bonds by their own house banks (the same thing has previously happened in Spain as well). Why have their banks talked them into taking such risks? The new bank regulations are in fact the main reason! European regulators have wittingly or unwittingly promoted the transfer of bank risk to widows and orphans – literally.

We are again in a situations where financial time moves faster than political time. The way out of the corner than central banks have painted themselves in is more fiscal spending in the US and Europe, which have plenty of slack resources and infrastructure needs, which provide the biggest GDP bang for each government dollar spent. But aside from the fact that it takes time to design and launch and infrastructure spending plan (even obvious stuff like fixing bridges and filling potholes takes time to sort out), we have a much bigger ideological problem, that that sort of thing is seen as an economic taboo by mainstream economists. And worse, too many of those same economists are treating financial-system-destroying negative interest rates as the fix for underperforming economies.

I don’t see any happy ending to this movie.

“I don’t see any happy ending to this movie.”

Nor do I.

Common sense dictates that having some actual cash in hand is a pretty good idea right about now. I’m not going to panic, but having some folding cash and some of that barbarous relic at home is on the agenda.

‘The way out of the corner than central banks have painted themselves in is more fiscal spending in the US and Europe.’

From the electoral calendar, we know that US fiscal policy is frozen for the coming year, at a deficit of about 2% of GDP.

‘Automatic stabilizers’ such as unemployment insurance don’t kick in until a recession is way underway, so those are irrelevant for now.

As the crisis of 2008 proved (in an election year, no less), political stasis can only be disrupted by scaring the bejeezus out of Congress with the claim that, ‘You must pass this TARP bill today without reading it, or the lights go out forever.’

Thus our ongoing showdown: Ms Market will keep puking on J-Yel’s valuable rug until J-Yel & Co capitulate. Lick that rate hike off the floor, Stanley.

People need to understand that CBs act to keep banks afloat, period, all the blather about boosting employment and GDP is just air cover. IOER pays them not to lend in an effort to repair their balance sheets. Oh, that and buying their worst toxic assets from them dollar-for-dollar.

If only they knew what money is and how it is created.

Look for the next form of QE, they will call it something else, probably outright equity purchases, then real estate, take a page out of Kuroda’s book. Kuroda has hit a wall, he already buys 100% of the JGB he issues from himself, on track to own 100% of Japanese equity ETFs

I do hope central banks and regulators (and governments) are regular NC aficionados. Somehow, though, unfortunately, I doubt that Yves is on their Christmas card list. But this is spot on and I do hope that policy makers can rouse themselves from their complacent slumber. My TBTF is already gearing up for some panicky cost cutting but POP’ing (people off the payroll) and network downsizing is a) a drop in the ocean compared to a balance sheet that “suddenly” — it’s actually entirely predicable if you’ve got a functioning brain cell — gets trashy and b) doesn’t solve the fundamental NIM issue. Put more succinctly, distressed assets in the form of impaired loans remain, long after you’ve shown the people the door.

Once nuance I will mention over and above what’s in the article (which are the nub of the current risk aversion and are the most important points) is that, this isn’t new news. Since the money lenders were thrown out of the temple (I started in the industry soon thereafter; it feels like it anyway) banking has been cyclical. Although we’re seeing an extreme iteration, squeezed NIM and/or asset impairments were always part of the industry. Banks — wisely, this was a good strategy — attempted to diversify earnings through product and service innovations. A very condensed version is that fee income was supposed to be more consistent and present less of a single-source-of-income risk than spreads on interest rates paid (to depositors) / charged (to borrowers).

In the wise words of a Scooby Doo villain, it would have worked too, If it hadn’t been for those pesky kids.

Unfortunately, the banks so crappified their products (and I’m probably being way too nice here — fraud might be a better way of putting it) and delivered such appallingly woeful levels of service that customers eventually got wise and kept their wallets shut. Either that, or regulators faced with one scandal after another were forced (under the mounting threat of torches and pitchforks) to try to have some semblance of clipping the banks’ wings and stop the outright conning and looting. Many banks have withdrawn from previously profitable markets because they either couldn’t make the outlandish levels of profit they had historically made any longer (insurance and sub prime lending for example) or the regulators couldn’t stand the bad smell any longer (high and ultra-high net worth banking services for example, which on some occasions bordered on being fronts for money laundering and tax evasion operations) and insisted on curtailments.

So now, even if the banks turned over a new leaf, went to bible study classes and were really really nice to their mothers and became model corporate citizens (yeah, right, like that is ever going to happen) it would be too late. They’re not in Kansas any more and they’re fresh out of ruby slippers. Which leaves them hoist on their own NIM petard.

Thanks for your kind words. This was broad brush so I’m glad you approve.

I don’t know if this is true in the UK, but one of the bad signs about priorities in the US has been the massive proliferation of retail branches, all offering commoditized services with only minor variations at the margin (for instance, I’ve found Citbank to be head and shoulders about other credit card companies in the caliber of their phone reps, even the supposedly vaunted Amex, despite the fact that Citi is subject to the same chargeback rules as the other Visa/MC members, while Amex in theory has more latitude). But my main bank (TD, which I;m at because my small and competent bank was gobbled up by them) has much better branch hours, with now shocking variations in the caliber of staff and complete incompetence in doing things that are not mass services, like domestic and international wires, which still ought to be easy peasy.

Now retail banking is only one business, but what is going on there (overinvestment in infrastructure to try to snag customers) strikes me as symptomatic of an underlying hunger for growth that simply was not there to be had, and those bad investments/expansion programs are now coming home to roost.

Yves,

How much of this on-the-ground presence is driven by regulators? I feel like one of the areas that they’ve made a push on is for banks to be less reliant on skittish money markets to fund their book of business. If you’re going to build up a base of stable retail/corporate customers so you can sit on their cash, you’re going to have to maintain a visible presence in the area.

Keep in mind that $1 NAV is going away this fall, unless you are in all US govt securities.

Is this a factor?

Yes, whatever geography a bank operates in, the business model has high operational gearing. The products in Retail or SME market segments are subject to constant maintenance needs by purchasers — changes of address, setting up new payments, cancelling old ones, clearing checks, renewing account goods like debit or credit cards on expiry, credit deaccessioning as accounts operate outside their facility, fraud and loss controls, wire services, cash handling, statements, telephony and online channels — the list goes on and on.

You simply can’t cease to respond to these servicing needs just because a bank might feel like it. And you have no idea how much a customer is going to cost you. Some customers don’t present any servicing needs for years at a time. Conversely, some are constantly generating account maintenance costs. My TBTF did a long study to try to discover how profitable this- or that- product was, on average. It — amazingly — failed to be able to work that out. It just could not work out its Cost of Goods Sold. As it couldn’t be sure what its costs were, it had no means of working out its profits. All it could aim to do was, from year to year, try to make as much in junk fees as it could get away with from those customers who were too naïve or indolent to change their behaviours.

Corporate and money centre areas are different, they too have high cost bases but they can charge significant fees for the expected-for white glove boutique services. And, by and large, the service provided is at least competent, if prone to fleecing of the unwary.

The only ray of hope might be that the banks are pretty much a cartel and do have some pricing power. But as you found, quality of service is, at best, variable and, at worse, non-existent. So if prices for products and/or service are raised, customer expectations rise with them but degraded capability in the banks’ service offer means that complaints skyrocket if you try to push fees for commodity transactions beyond the low (-ish) levels.

I still can’t quite believe an entire industry has been wrecked in less than a generation. But I suppose its happened to others, so there’s no particular reason why not Retail and SME finance.

The wrecking would happen to any industry if its participants were continuously coddled, bailed out, propped up, and supported despite whatever horrendous management, product, and customer service policies they pursued. Banks yell about “free market capitalism” but are about as far from that ideal as any industry ever was. We’re told they are the backbone of the economy and must never be allowed to fail, so we tolerate them capturing the regulators and breaking the law with complete and utter impunity.

If we’re going to have communism let’s at least get the kind that divides the spoils somewhat evenly, not the kind that pays the Komissars enough to buy their own private islands.

Keep seeking Mister Good Bar or aka free market… point deductions for being a rube…. or victim in waiting…

http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2016/02/04/senate-ethics-panel-has-issued-no-punishments-9-years/79704196/

PRISON, n. A place of punishments and rewards. The poet assures us that —”Stone walls do not a prison make,”but a combination of the stone wall, the political parasite and the moral instructor is no garden of sweets. Devils Dic.

overinvestment in infrastructure to try to snag customers

This also goes to the pattern observed in Apple software quality decline in today’s links:

Apple takes its eye off the ball: Why Apple fans are really coming to hate Apple software

And I think we have been seeing this across all industries, it’s the hallmark of corporatist managerialism; service and/or product quality have been deemed disposable burdens if they don’t generate (sufficient) profit growth (even flat profit is discredited).

This leads to effective cannibalization of existing processes and products in order to replace them with lower-cost low-(non-)performing replacements (hailed as “new! improved!”), when they are not simply eliminated. Tons of this in the software sector. This also means that genuinely good/worthwhile improvements are 1) used to prop up the flood of crap and 2) have their benefits diminished because the environments they operate in/on are degrading. For (random) example, implementation/delivery of alternative energy sources is hampered by declining/unmaintained infrastructure.

The fundamental premise if business-as-usual is “what worked well today will work as well tomorrow and forever thereafter”, ignoring maintenance requirements (as well as limits of capability). The managerialist strategy is “don’t fix, replace or eliminate”, because repair tends to attract less attention/”merit”. Combining these two, one is well screwed.

Interestingly, Amazon is investing bricks and mortar bookstores too. And trucks. I don’t get this. Maybe the search for real profits in real businesses, instead of financialized bezzles?

And aren’t all the kids these days supposed to be on cellphones? So why bank branches proliferating? As Yves points out, a vault is expensive; it’s not like they can lower a box from a helicopter and repurpose it for some other retail purpose. Again, I don’t get this.

I worked in a bookstore when Borders moved in two doors down and crushed us, SOP for them. Barnes & Noble moved in a couple of blocks away, and is still there despite Amazon crushing Borders.

Last year, I found a book on the B&N site that was in-stock at the store. When I picked it up, it cost more than listed on the website, and the manager told me it was cheaper to order it online. I also heard her relief when she didn’t have to work at the in-house Starbucks.

My takeaway is the bricks-&-mortar site is a warehouse that may as well sell the books, since you pay more, and the magazine section is to help draw the people in for the lattes. They readily ship the books between cities and draw from the total inventory to fill orders. The trucks can also haul more than books, if things work right they get to ship the books on someone elses nickle.

there is an easy answer to that. We are physical beings who live in the physical world. And believe it or not most people need actual real life human interactions. Those ideas have been lost for awhile but are coming back slowly. Technology may be racing ahead but humans are basically unchanged from 500 years ago.

Speaking of which, why doesn’t NC hold some type of cocktail party or gathering some day so people can meet you guys?

I think part of the retail boom is/was to hide CRE looses. Instead of having a bad asset, you have a new retail branch.

I’ve also noticed this because the huge new space has only a few people working there, and they are just human interpreters for the TBTF website.

In NYC, I’ve seen bank branches replace perfectly viable businesses, like wine/liquor stores (as in the landlord jacked up the rent and the bank went in). Plus here these are retail space with apartment buildings above, so no CRE angle (as in the retail space is just extra income relative to the residential rental/coop income). And it costs a LOT of money to put a vault in, which makes it difficult to convert it from being a bank branch back to other uses.

In the tradition of Jeremy Corbyn and to a lesser degree Bernie Sanders, if we must do negative interest (of course sane public policy spending and social programs would be better) then let’s have Negative Interest Rates For The People not corporations and the rich.

Pay The Little People who borrow money an interest rate for doing so. If the negative interest rate is !%, pay borrower $1,000 per year for every $100,000 borrowed.

If banks pay The Little People 1%, the Fed can pay the banks 1.1% or whatever rate that makes sense for banks to do this.

But… but… isn’t that SOCIALISM? And how quick will the little people become only big people, as the process of capture works its magic?

And besides, it’s not TRADITION to transfer wealth to little people like that! Whatthhell? Pay people to borrow money, to get into debt? Compounding is only supposed to work going the other way!

There’s no hint of any kind of common goal or organizing principle in any of this, none of the homeostatic feedbacks and limits that our little-people bodies possess inherently. Just lots of little pockets of greedy malignancy, figuring out how to trick the rest of the body into growing larger vessels to convey more of the nutrients and resources to build little, and growing, local tumors that eventually kill the organism…

What outcomes do “we,” whoever the hell “we” is, want from “our” (implies, dishonestly, agency and ownership) political economy?

Do the Bernie-ites have any plans or hopes for postal banking, since they are looking at other earlier forms of political-economic homeostasis? Of course the disease process is so very, very far advanced, and the patient is looking fearful and cachexic…

Sanders does support a Post Office Bank.

Excellent post!

The only way for this movie to end less tragically is for us to fire the producers, directors, and major actors. We do, indeed, “have a much bigger ideological problem” here. The last few years have revealed that the Davos elite would rather sit atop a smoldering ruin, than do anything sensible to begin addressing the huge systemic problems facing the world economy.

while stealing the plebes cash…..under the guise that having any is a crime!

“Deutsche on Tuesday is soft again, but off just 2 per cent after it reassured investors on its finances, and this is helping somewhat to calm the mood in Europe.” FT

BAYONET, n. An instrument for pricking the bubble of a nation’s conceit. Devils Dic.

Re the issue of selling corporate debt to widows and orphans, it is a very old practice to do so. Keatings Lincoln savings and load did it for example. It is a simple case of a lack of sufficient financial paranoia on the part of those investing. Tell people to assume no one looks out for your interest period, and to tell salesfolks there is a nice hot place for them.

I am a fan of public banking – or banking without profit. I am wondering whether the Bank of North Dakota, smack dab in the middle of the oil swoon, has been badly hurt by the downturn. I like to think that they are healthier than most, but I would be interested in a pro’s evaluation of their status. My simple thesis is that profit-seeking encourages excessive risk-taking and that absent that fetish, risk-taking declines.

As far as I can tell, the Bank of North Dakota is completely run by the business establishment of that state. The returns to the people of North Dakota are miniscule.

Speaking of TD, Zero Hedge has a dismal chart on Canadian banks .. being headed toward doomsday.

Good think ole Justin still is living in a honeymoon period with the folks and that he appears to have appointed a Finance Minister who might just “get it”.

Meanwhile, Wolfgang and the CEO of Deutschebank have just assured us the bank is “rock solid”. What rocks do you supposed they are talking about?

Great article.

Ya. TD showed up in the middle of the list of 20 least_well_capitalized banks in the world. Plus you have to wonder if Vancouver real estate is really a million Cbucks and crossing over the border from Detroit is really 600K Cbucks. Plus, who has all those tar sands loans?

I just moved most of my idle cash out of TD Ameritrade. It’s FDIC insured, but I figure why wait and see if there’s any ammo in that bazooka.

He better hope it’s not talc :)

I think the rocks might be crack.

‘Unobtainium’

as in ‘We have what you need….and it ain’t coming back sucker!!’

Wanting to know how the Bank of North Dakota is doing in this environment – note that ND is the epicenter of the oil bust – I took a look. Turns out this public bank had record profits, suggesting that profit-seeking (greed) absent adequate internal controls, leads to excessive risk taking – highly profitable when those bets pay off, terrible when they don’t. bismarcktribune.com/news/local/govt-and-politics/bank-of-north-dakota-moves-on-financial-center-project/article_45df2ece-435b-5139-bf6d-6f849c2bc2ac.html

And, better yet, the Bank of North Dakota has been in business since 1919. Which tells me that it knows a thing or two about risk management.

The Bank of North Dakota is the only state-owned facility of its type in the United States.

Goddam socialists!

Interestingly the Izabella Kaminska post is part of the – long running – “Death of Banks” series on FT AV. Its worth checking out some of the other posts in this series. Also, as I recall, Frances Coppola has been making similar points as to whether the current models of banking (esp the TBTF ones) can survive in a semi-permanent environment of low (or -ve) interest rates and deflation.

“I don’t see any happy ending to this movie. ”

But we have the book! Ben Bernanke and Bernankenomics. Should be good for a laugh or two.

The deregulators: “but this time it’s different.”

Thanks for this excellent post.

Perhaps this is a small piece of the Macro-Momentum Bubble that JPM is playing with:

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/financetopics/davos/12108569/World-faces-wave-of-epic-debt-defaults-fears-central-bank-veteran.html

Maybe I’m reading this wrong but it seems to be a piece recommending saving the banks as the economy then would be saved?

Or what is the proposed alternative solution to dealing with bust banks?

More a case that dysfunctional banks produce a dysfunctional economy. See the regular coming attraction “Japan and the Banks of the Living Dead — Zombie Apocalypse”.

Effective bank resolution is NOT difficult. The basic recipe is 1) wipe out equity and unsecured creditors 2) restructure not-completely-underwater borrowers, recognise losses then write off hopelessly non performing loans and 3) complete clear out of existing diseased management with, finally, 4) recapitalisation — under government ownership if appropriate.

Forced mergers, extend-and-pretend, accounting gimmicks and monetary action on its own won’t fix things.

The central tenet of the post seems to be about this

I suppose it depends on the meaning of the word ‘rescue’. Does it mean save the bank (or rather save all its investors) or is it about getting resolution for insolvent banks (the way you proposed)?

Rescue at a minimum means:

1. Backstop depositors credibly; make sure you do what you what you can to protect uninsured depositors (as in they have no guarantee but you don’t want them so much at risk that they’ll feel compelled to leave, rationally, at the first hint of trouble)

2. Have a mechanism for resolving banks (take them over and keep running them as the FDIC does).

“Resolve” might have been a better word, but in Europe, they think they do have a resolution plan, which is basically to liquidate them. So I didn’t want to use that word.

It’s like the difference between bankruptcy in the US v. the rest of the world. We have both Chapter13, which tries and usually succeeds in reorganizing the business so it can carry on. Chapter 7 is a liquidation. FDIC resolutions area banking version of Ch. 13. The Europeans think that their plan is kinda-sorta resolution like, but the way they’ve got it set up, it will lead to liquidations in most cases unless they can arrange shotgun marriages.

business re-organizations in this country are Chapter 11s not 13’s. 13s are for individuals.

To my knowledge, european banks use euribor (tipically 1 yr interbank) as a reference for their long-term loans. I interpret that the flattening of the yield curve encourages bank lending over bank buying bonds.

Am I wildly wrong on this?

Don’t forget about the top 4 US Banks holding $166 Trillion in derivatives, that’s right Trillions.

What could possibly go wrong?

The data is here, see table 5 : http://www.occ.gov/topics/capital-markets/financial-markets/trading/derivatives/dq315.pdf

“POOF”

So, go long entropy?

“So, go long entropy?”

thanks, that made me laugh. I have a science background so it struck a chord with me and it’s an excellent idea.

When main stream economists are using fatally flawed economics the chances of them coming up with a working solution are zero.

Which way is up?

Is today’s economics upside-down?

40 years ago most economists and almost everyone else believed the economy was demand driven and the system naturally trickled up.

Now most economists and almost everyone else believes the economy is supply driven and the system naturally trickles down.

Economics has been turned upside down in the last 40 years.

Let’s have a look at things from the perspective of the old economics.

How is the global consumer these days?

1) The once wealthy Western consumer has had all their high paying jobs off-shored. As a stop gap solution they were allowed to carry on consuming through debt. They are now maxed out on debt.

2) Japanese consumers have been living in a stagnant economy for decades.

3) Chinese and Eastern consumers were always poorly paid and with nonexistent welfare states are always saving for a rainy day. Western demand slumped in 2008 and the debt fuelled stop gap has now come to an end.

4) The Middle Eastern consumers are now too busy fighting each other to think about consuming anything and are just concerned with saying alive.

5) South American and African consumers are busy struggling with economies that are disintegrating fast.

No demand, no surprise.

Modern, mainstream economics is a disaster area; it also has two further fundamental flaws in its assumptions:

1) Doesn’t differentiate between “earned” and “unearned” wealth

Adam Smith:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Like most classical economists he differentiated between “earned” and “unearned” wealth and noted how the wealthy maintained themselves in idleness and luxury via “unearned”, rentier income from their land and capital.

We can no longer see the difference between the productive side of the economy and the unproductive, parasitic, rentier side.

The FIRE (finance, insurance and real estate) sectors now dominate the UK economy and these are actually parasites on the real economy.

Constant rent seeking, parasitic activity from the financial sector.

Siphoning off the “earned” wealth of generation rent to provide “unearned” income for those with more Capital, via BTL.

Housing booms across the world sucking purchasing power from the real economy through high rents and mortgage payments.

Michael Hudson “Killing the Host”

2) Ignores the true nature of money and debt

Debt is just taking money from the future to spend today.

The loan/mortgage is taken out and spent; the repayments come in the future.

Today’s boom is tomorrow’s penury and tomorrow is here.

One of the fundamental flaws in the economists’ models is the way they treat money, they do not understand the very nature of this most basic of fundamentals.

They see it as a medium enabling trade that exists in steady state without being created, destroyed or hoarded by the wealthy.

They see banks as intermediaries where the money of savers is leant out to borrowers.

When you know how money is created and destroyed on bank balance sheets, you can immediately see the problems of banks lending into asset bubbles and how massive amounts of fictitious, asset bubble wealth can disappear over-night.

When you take into account debt and compound interest, you quickly realise how debt can over-whelm the system especially as debt accumulates with those that can least afford it.

a) Those with excess capital invest it and collect interest, dividends and rent.

b) Those with insufficient capital borrow money and pay interest and rent.

Add to this the fact that new money can only be created from new debt and the picture gets worse again.

With this ignorance at the heart of today’s economics, bankers worked out how they could create more and more debt whilst taking no responsibility for it. They invented securitisation and complex financial instruments to package up their debt and sell it on to other suckers (the heart of 2008).

Great post Yves,

Everyone is searching and groping for explanations in an attempt to make sense of things. It can’t be done! The central banks have taken the global economy down the proverbial rabbit hole where nothing makes sense. Nobody knows where this leads or how it ends but it ends at some point and it’s going to be ugly, possibly very ugly and that is scary.

What strikes me as so odd is that people are still looking to the CBs for answers when it is clear that they don’t have any. In fact it’s worse than that because the CBs are fundamentally the source of the problem. They allowed the world to go on a 30 credit binge and now that the consequences are here nobody wants to acknowledge that they screwed up or deal with the ramifications in a honest manner so they just double down on their idiotic ideas and gin up even more credit in the hopes of keeping what quite literally amounts to a pyramid scheme going. It’s insane!

i didn’t have the stomach for this yesterday. depressing. i guess there is an outside chance that the changes that are needed have been drawn up and maybe incremental steps toward a new financial system are more at hand than we think…

World leaders are on the case:

“Leading financial journalist Martin Wolf has reported that all financial crises since 1971 have been preceded by large capital inflows into affected regions. While ever since the seventies there have been numerous calls from the global justice movement for a revamped international system to tackle the problem of unfettered capital flows, it was not until late 2008 that this idea began to receive substantial support from leading politicians. On September 26, 2008, French President Nicolas Sarkozy, then also the President of the European Union, said, “We must rethink the financial system from scratch, as at Bretton Woods.”[23]

On October 13, 2008, British Prime Minister Gordon Brown [24] said world leaders must meet to agree to a new economic system:

“ We must have a new Bretton Woods, building a new international financial architecture for the years ahead. ”

However, Brown’s approach was quite different from the original Bretton Woods system, emphasising the continuation of globalization and free trade as opposed to a return to fixed exchange rates.[25] There were tensions between Brown and Sarkozy, who argued that the “Anglo-Saxon” model of unrestrained markets had failed.[26] However European leaders were united in calling for a “Bretton Woods II” summit to redesign the world’s financial architecture.[27] President Bush was agreeable to the calls, and the resulting meeting was the 2008 G-20 Washington summit. International agreement was achieved for the common adoption of Keynesian fiscal stimulus,[28] an area where the US and China were to emerge as the world’s leading actors.[29]

Yet there was no substantial progress towards reforming the international financial system, and nor was there at the 2009 meeting of the World Economic Forum at Davos [30]

Despite this lack of results leaders continued to campaign for Bretton Woods II. Italian Economics Minister Giulio Tremonti said that Italy would use its 2009 G7 chairmanship to push for a “New Bretton Woods.” He had been critical of the U.S.’s response to the global financial crisis of 2008, and had suggested that the dollar may be superseded as the base currency of the Bretton Woods system.[31] [32] [33]”

In due course the historians will be writing about the 2008 crisis with 20/20 hindsight and the monetary errors will be laid bare. There was no easy solution to the 2008 crisis but the reliance on monetary policy alone with little or no fiscal stimulus will be seen as a major policy blunder. A massive and well designed fiscal stimulus program with an emphasis on productive infrastructure projects would have been a wise choice. But, then again how was that going to happen with one of the world’s most corrupt and incompetent political systems?