Yves here. Get a cup of coffee. This is a very readable, information-rich post on what the Fed does and does not do, with emphasis on the nitty-gritty of monetary policy. If you are time-pressed, read the last item in the FAQ first, which is a terse item-by-item debunking of widely made, inaccurate statements about the Fed.

By Eric Tymoigne. Originally published at New Economic Perspectives

Previous posts studied the balance sheet of the Fed, definitions and relation to the balance sheet of the Fed, and monetary-policy implementation. In this post, I will answer some FAQs about monetary policy and central banking. Each of them can be read independently.

Q1: Does the Fed target/control/set the quantity of reserves and the quantity of money?

The Fed does not set the quantity of reserves and does not control the money supply (M1). It sets the cost of reserves; that’s it.

In terms of reserves, the Fed was created to provide an “elastic currency,” i.e. to provide monetary base according to the needs of the economic system in normal times and panic times. It would be against this purpose to implement monetary policy by unilaterally setting the monetary base without any regards for the daily needs of the economy system.

In terms of the money supply, the Fed has no direct influence. Even Federal Reserve notes (FRNs) are supplied through private banks, and banks supply only if customers ask for cash. The Fed does not force feed FRNs to the public, i.e. FRNs can’t be “helicopter dropped” via monetary policy. If the Fed did this, not only would it operate in a way that goes against the Federal Reserve Act, but also it would lead people to take the FRNs, bring them to banks, banks would have more reserves, FFR would fall, Fed would remove excess reserves to bring FFR back up—back to square one.

The Fed may have an indirect influence on the money supply through changes in its FFR target because changes in the cost of credit may change the willingness of economic units to go into debt, but the link is tenuous (see Q10).

Q2: Did the Volcker experiment not show that targeting reserves is possible?

In the 1970s, the Monetarist school of thought gained some influence in policy circles. Monetarists argued that there is a close relation between the quantity of reserves and the money supply, and that a central bank’s role is to control the quantity of reserves in order to influence the money supply and ultimately inflation. The Fed, under the leadership of Paul Volcker, tried to implement a monetary-policy procedure that aimed at more closely targeting reserves and monetary aggregates, with the hope of taming a double-digit inflation rate.

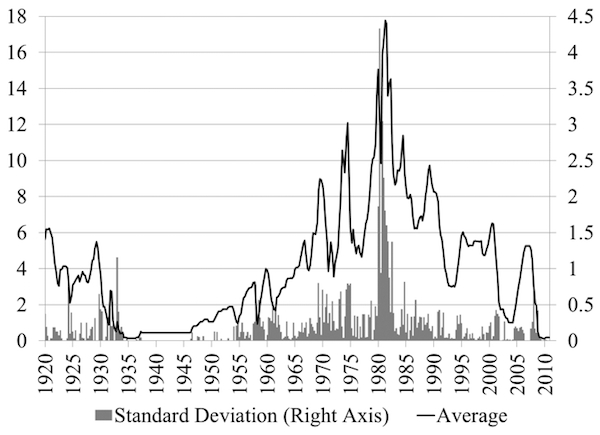

Practically what the Fed did is change interest-rate targeting from a narrow range to a wide range, which rose the level and volatility of the FFR dramatically (Figure 1). The Fed did NOT allow the FFR to move freely as targeting a total quantity of reserves would imply.

Figure 1. FFR, Monthly Average and Standard Deviation

Source: Federal Reserve Board, NY Federal Reserve Bank

There is a debate about how truly “Monetarist” the Volcker experiment was, and this debate is reflected in the FOMC discussions of the time

- ROOS. Well, if the level of borrowing comes in higher than we would anticipate, [can’t] you reduce the level of the nonborrowed reserves path accordingly? Can’t you adjust your open market operations for the unexpected bulge in borrowing or the unexpectedly low borrowing if you ignore the effect on the fed funds market? Can’t you just supply or withdraw reserves to compensate for what has happened?

[…]

CHAIRMAN VOLCKER. The Desk can’t [adjust] in the short run. It’s fixed. In a sense they could do it over time if people are borrowing more, as they may be now. They seem to be borrowing more than we would expect, given the differential from the discount rate. But in any particular week it is fixed.

- ROOS. Do we have to supply the reserves?

CHAIRMAN VOLCKER. We have to supply the reserves.

- ROOS. [Why] do we have to supply the reserves? If we did not supply those reserves, we’d force the commercial banks to borrow or to buy fed funds, which would move the fed funds rate up.

(FOMC meeting, September 1980, page 6)

Mr. Roos was deeply dissatisfied with the Fed still having a FFR target, albeit in the form of a wide range. While the Fed had a total-reserve growth target related to the 3-month growth rate of M1, if banks needed more than what was targeted, the Fed would supply extra reserves in order to relieve pressures on the FFR. Roos argued against this lenient reserve targeting and was for a total abandonment of any FFR targeting and a strict targeting of total reserves. Here he is in 1981:

I think there’s a very basic contradiction in trying to control interest rates explicitly or implicitly and achieving our monetary target objectives. And I would express myself as favoring the total elimination of any specification regarding interest rates.

(Roos, FOMC meeting, February 1981, page 54)

Most Federal Open Market Committee members were against that position, on the ground that the role of the Fed is precisely to promote an elastic monetary base. The Fed was not created to dictate what the quantity of reserves ought to be but too eliminate liquidity problems through smooth interbank debt clearing at par, lender of last resort, and interest-rate targeting. In addition, banks mostly hold reserves because they are required to, so if the Fed does not supply enough reserves to meet the requirements then banks will break the law.

The experiment was a monetary-policy failure. The Fed was never able to reach its reserve or money targets and the experiment contributed to massive financial instability and a double-deep recession. On may even doubt that it contributed significantly to the fall in long-term inflation, which had more to do with the downward trend in oil prices, oil-saving policies, and greater international labor competition:

May I remind you that we shouldn’t take too much credit for the price easing? I never thought we were totally at fault for the price increases that we suffered from OPEC and food; and I don’t think the fact that OPEC and food have calmed down has a great deal to do with monetary policy per se, except in the very long run.

(Teeters, FOMC meeting, July 1981, page 46)

The Volcker experiment was, however, a public-relation success. Most FOMC members knew that reserve targeting was not possible but, it allowed them to claim that they were not responsible for the high interest rates of the period:

I do think that the monetary aggregates provided a very good political shelter for us to do the things we probably couldn’t have done otherwise.

(Teeters, FOMC meeting, February 1983, page 26)

I think the important argument, and really the reason why we went to this procedure, was basically a political one. We were afraid that we could not move the federal funds rate as much as we really felt we ought to, unless we obfuscated in some way: We’re not really moving the federal funds rate, we’re targeting reserves and the markets have driven the funds rate up. That may have had some validity at the time, and I had some sympathy for it. But as time goes on, I’ve become more and more concerned about a procedure that really involves trying to fool the public and the Congress and the markets, and at times fooling ourselves in the process.

(Black, FOMC meeting, March 1988, page 12)

Of course the high and volatile FFR was precisely the result of the change in monetary-policy procedures. If needed, some FOMC members were willing to do the same thing in the future:

Well, I have only a little to add to all of this. I think Tom Melzer is probably right: We’re going to need to shift the focus to some measure or measures of the money supply as we proceed here if we can, both for substantive reasons and also because that has some political advantages as well, as we go forward.

(Stern, FOMC meeting, December 1989, page 50)

Q3: Is targeting the FFR inflationary?

With the failure of the Volcker experiment, the FOMC entered a period of operational uncertainty until the mid-1990s. The Fed was back on a tight FFR target procedure (there was still a wide range until 1991 but the Fed targeted the middle of the range) and this was deeply unsatisfactory to FOMC members.

We’ve advanced from pragmatic monetarism to full-blown eclecticism.

(Corrigan, FOMC meeting, October 1985, page 33)

No, I would say that we have a specific operational problem that we have to find a way of resolving. Just to be locked in on the federal funds rate is to me simplistic monetary policy: it doesn’t work.

(Greenspan, FOMC meeting, October 1990, pages 55–56)

In a world where we do not have monetary aggregates to guide us as to the thrust of monetary policy actions, we are kind of groping around just trying to characterize where the stance is.

(Jordan, FOMC meeting, March 1994, page 49)

The Fed was unwilling to disclose that it was targeting the FFR, and continued to announce a targeted growth ranges for monetary aggregates even though it did not use them for policy purpose.

[In response] to talk that says we can significantly influence this – or as the phraseology goes that if we lower rates, we will move M2 up into the range – I say “garbage.” Having said all of that, I then ask myself: ‘What should we be doing?’ Well, we have a statute out there. If we didn’t have the statute, I would argue that we ought to forget the whole thing. If it doesn’t have any policy purpose, why are we doing it? By law [we have] to make such forecasts. And if we are to do so, I suggest that we do them in a context which does us the least harm, if I may put it that way.

(Greenspan, FOMC meeting, February 1993, page 39)

We do not, in fact, discuss monetary policy in terms of the Ms between Humphrey-Hawkins meetings. Don Kohn dutifully mentions them because he thinks he ought to, but that is not the way we think about monetary policy.

(Rivlin, FOMC meeting, February 1998, page 91)

To announce to the general public that the FOMC was targeting the level of the FFR would be going against all the Monetarist principles (reserve targeting, money multiplier theory, quantity theory of money). By targeting an interest rate, and so having an elastic supply of reserve (horizontal supply at a given FFRT), it seemed to indicate that the Fed was no longer able to control the money supply and so inflation. FOMC members themselves believed that was the case:

Many analysts, both inside and outside the Fed, argued that using the Federal funds rate as the operational target had encouraged repeated over-shooting of the monetary objectives. (Meulendyke 1998 49)

Talking about the FFR target became a taboo and “the Committee deliberately avoided explicit announced federal funds targets and explicit narrow ranges for movements in the funds rate” (Kohn, FOMC Transcripts, March 1991, page 1):

I must say I’m still quite reluctant to cave in, if you will, on this question that we can do nothing but target the federal funds rate.

(Greenspan, FOMC transcripts, March 1991, page 2)

As a practical matter we are on a fed funds targeting regime now. We have chosen not to say that to the world. I think it’s bad public relations, basically, to say that that is what we are doing, and I think it’s right not to; but internally we all recognize that that’s what we are doing.

(Melzer, FOMC transcripts, March 1991, page 4)

We will see later why the entire Monetarist logic is flawed. Monetary policy is always about providing an elastic supply at a given interest rate. There is nothing intrinsically inflationary about this. Having an “elastic currency” usually just means supplying whatever amount of reserves banks want, and usually banks don’t want much.

While all this was very well understood by many economists long before Volcker experiment (see for example Kaldor), it took the FOMC member until the mid-1990s to get comfortable with FFR targeting.

Q4: What are other tools at the disposition of the Fed?

Monetary policy is always about setting at least one interest rate. While today the Fed operates mostly through the Fed Funds market, it has other tools at its disposition to help influence interest rates.

One is the (re)discount rate, the rate at which banks can obtain borrowed reserves. This interest rate is now higher than the FFR target but from the mid 1960 until 2003 the discount rate was usually below the FFR target. The Fed decided to put the discount rate above the FFR target to put a ceiling on the FFR and so limit upward volatility in FFR.

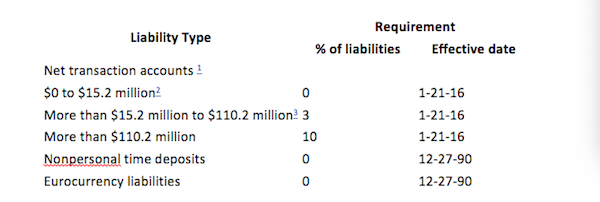

Reserve requirement ratios can also be used to help target the FFR. These ratios state how much total reserves banks must keep on their balance sheet in proportion of the checking account they issue. This is what the ratios look like today in the US

If a bank issued less than $15.2 of checking accounts it does not have to have any reserves, 3% between 15.2 to $110.2 million worth of outstanding checking accounts, 10% beyond that.

While these ratios are often discussed in relation to the ability of banks to create checking accounts, their actual purpose is once again to help target the FFR. By raising reserve requirement ratios, the demand for reserves becomes more predictable given that a greater proportion of the reserves available must now be held by banks. With a more stable demand for reserves comes less volatility in FFR (see this for more)

Q5: What is the link between QE and asset prices?

The link can’t be one where banks have excess reserves that they use to buy asset prices in the secondary market. As we saw in a previous post, banks can’t do this as a whole. They could buy from one another but if they all have reserves they want to get rid of, then this is not possible because no bank wants to sell assets for reserves.

The link goes through the following channels:

- The Fed buys large amounts of securities from banks which raises their prices and so lower their yield

- As yields on these securities fall, economic units seek assets that provide a higher yield. They will look for assets with large expected capital gains, especially so knowing that others are experiencing the same problems and are “searching for yield.” They will continue to buy these securities, which will raise their prices (and so lower their yield), until all rates of return are equalized once adjusted for risks.

Financial companies have to do the second step because they have to meet target rate of returns that they promised to their stakeholders. Pensioners expect a substantial rate of return from their pension funds, wealthy individuals expect a substantial rate of return from hedge funds, mutual funds shareholders wants a substantial rate of return…and they all check every quarter if financial companies stay on course to meet the promised target. Long-term treasuries used to provide a safe and simple way to meet this promise, no longer so.

Bill Gross (a well-known portfolio manager who specialized in bond trading) brought the point forward very clearly when he hoped that the Fed would raise the FFR to make it easier to reach targeted rates of return. He noted that low FFR prevents savers to earn enough to pay for healthcare, retirement and other costs because return on financial assets are so low compared to the expected 7-8%. If the Fed does not help by raising the FFR, financial-market participants will take large risks on their asset side (speculative, high credit risk, and structured securities) and liability side (high leverage) to try to reach their targeted rate of return.

There is a broad problem though. In an economy in which the growth of standard of living is low, why should anyone expect that demanding 7-8% be sustainable? Those can only be achieved through capital gains and leverage and the combination of these two is highly toxic (we will see why later in a post about financial instability). Instead of the Fed raising its FFR, it should be the rentiers who should reduce their expectations of rate of return. An economy that growth at 2% per year cannot sustainably provide a real rate of return higher than 2%, even that is a stretch. Other means must be used to meet the challenge of an aging economy than increasing the financialization of the economy.

Q6: How and when will the level of reserves go back to pre-crisis level? The “Normalization” Policy

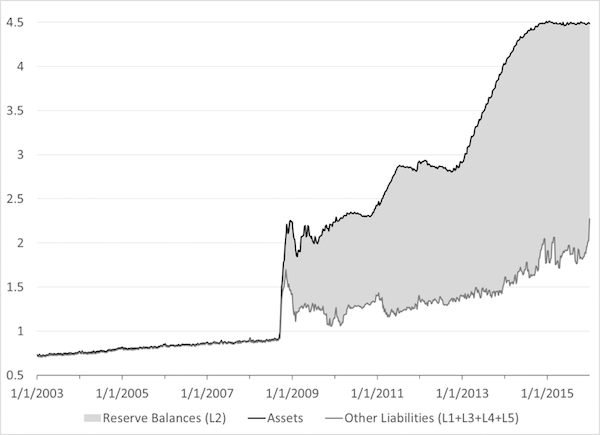

Normalization policy means the willingness of the Fed to do two things: 1-to raise the FFR to more normal level 2- to reduce the size of its balance sheet in order to return the proportion of excess reserve to pre-crisis levels. The previous blog showed how this would be done for interest rate. Regarding reserve balances, a previous blog showed that their dollar amount is determined as follows:

L2 = Assets of the Fed – (L1 + L3 + L4 + L5)

Most of L2 is now composed of excess reserves, which is unusual. A graphical representation of this balance-sheet identity is Figure 2.

Figure 2. Balance Sheet of the Fed and Reserve Balances

Sources: Federal Reserve Series H.4.1.

The implication of this balance-sheet identity is that reserves balances will fall either when assets of the Fed decline given other liabilities, or when the other liabilities of the Fed rise given assets. Let’s look at each case in turn.

Given other liabilities than reserves balances, reserves won’t go back down until the following happens to the securities held by the Fed:

- Securities ISSUED BY NON-FED-ACCCOUNT HOLDERS mature (let’s call them “private securities” to simplify)

- The Fed decides to sell some securities to banks.

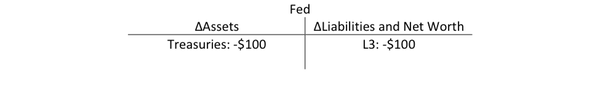

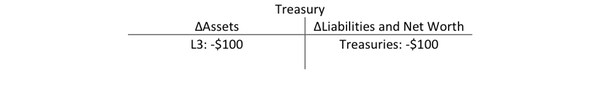

If the Fed let treasuries mature the account of the Treasury (L3), not reserve balances, will be debited:

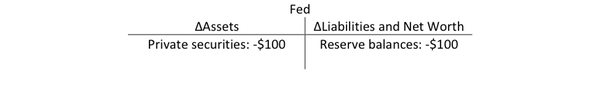

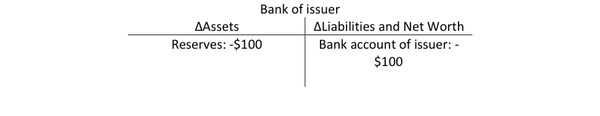

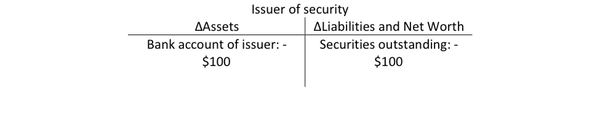

When private securities held by the Fed, currently agency-guaranteed MBS, mature the following will occur:

If all MBS held by the Fed matured at once, that would reduce reserve balances by almost $2 trillion (the Fed does not plan to sell most of the MBS it holds).

Given assets, reserve balances will go down if banks need to make payments to other account holders or if banks convert reserve balances into cash. For example, if the Treasury ran fiscal surpluses reserve balances would fall as funds would move from L2 to L3. While the Fed may ask, and has asked, for the Treasury’s help in managing monetary policy (more on this in the next blog), the Fed has mostly no control over what happens to liabilities that impact reserve balances.

One may note to conclude that, besides changes in assets and liabilities, another way to reduce excess reserves without reducing the amount of reserves is to raise reserve requirement ratios. As to when the reserves will be back to their usual level, nobody knows. The pace of decline will change as the economic environment change.

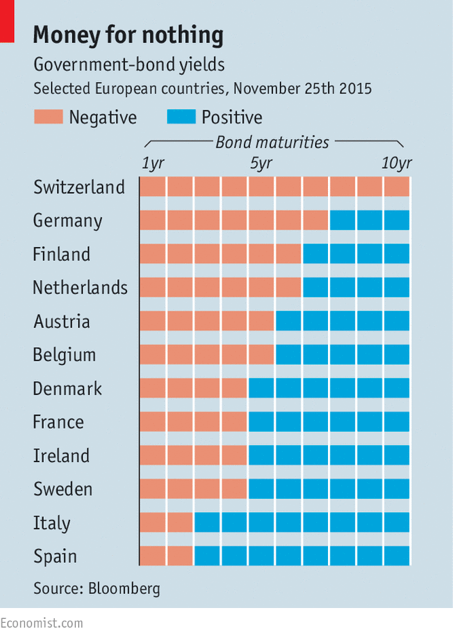

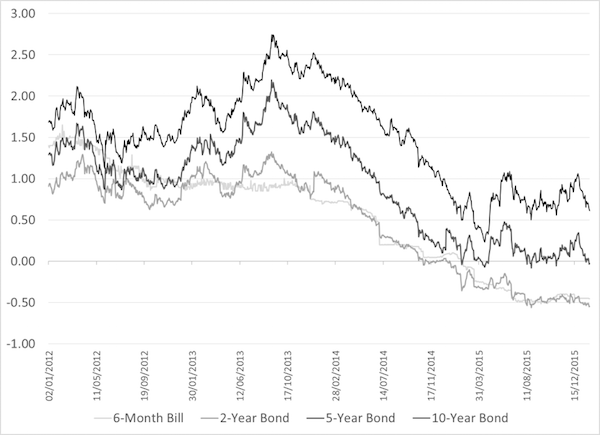

Q7: Is there a zero-lower bound?

This question is so 2013! There is no lower bound and I have an old post that explains all this in more details. Remember that the Fed sets the price of reserves. It can set it wherever it wants: “It is the Fed’s way or the highway.”

Which interest rate can be below zero? Any of them as long as the Fed is committed to do so.

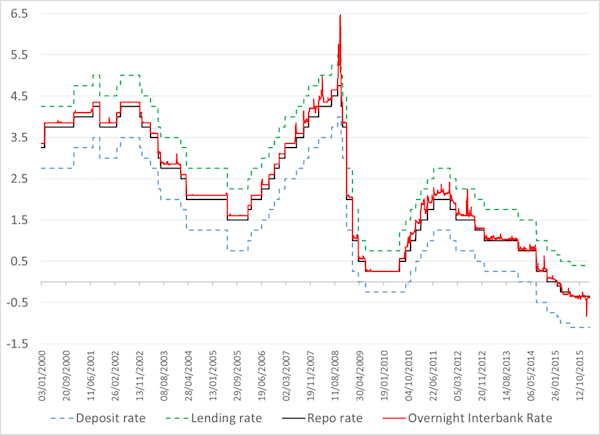

The interest rates used in the corridor framework (DWR, FFR, IOR) are under total control of the Fed so they are easy to make negative. The Swedish central bank shows us how this is done under a corridor framework (Figure 4). The Swiss central bank shows us how it is done with a negative overnight interbank rate range (a negative FFR range) (Figure 3).

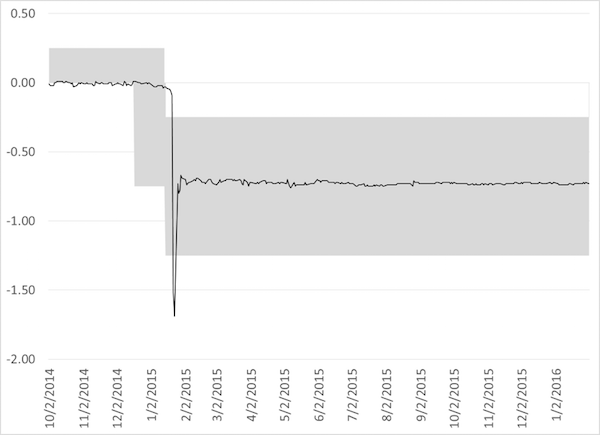

Figure 3. Target Overnight Rate Range and Daily Overnight Rate, Swiss National Bank, Percent

Figure 4. Corridor of the Sveriges Riksbank, Percent

I’m not sure this claim is really explored? Yes, literally piles of cotton and ink wouldn’t be dropped from the sky (that would be a Treasury program, not FRB; and very environmentally unsound as it would waste a lot of oil and cause noise, air, and GHG pollution).

But the Federal Reserve has claimed the power to do anything under unusual and exigent circumstances. They bailed out investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley for goodness sakes by allowing them to become bank holding companies and giving them below market rate loans and other subsidies. They gave below market rate loans to AIG and other debtors so that creditors like Goldman Sachs could get paid rather than have to eat the losses they themselves created through fraud and recklessness. On and on, that is the very definition of helicopter money in our contemporary payments systems where economic activity happens inside machines, not through banknotes. It’s just that the helicopter money wasn’t dropped over Manhattan, KS. It was dropped over Manhattan, NY. That’s a policy choice, not an operating constraint.

The Federal Reserve Act explicitly allows for “Discounts for individuals, partnerships, and corporations”.

I’m not saying that’s a good idea; public policy should provide payments, not loans, to people in need [that’s why monetary policy is largely irrelevant as a solution to inequality]. But I think it misreprestents the unprecedented racket in which the Fed has and continues to engage to protect financial fraudsters from their own criminal acts and mismanagement to claim there are substantive hurdles to the Fed disbursing money more broadly if its leaders were so inclined. If the past couple decades demonstrates anything in monetary policy, it is that the Fed’s only ‘constraint’ is the tasks assigned to it by the political structure in Washington.

The Fed owns $4.2 trillion of securities at this point. There are no legal principles guiding that scale of helicopter money. It is simply a choice made by people in expensive suits.

http://www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed/section13.htm

First a note to everyone: you probably noticed that editing went under the truck for this post, I did some additional editing on NEP (sorry).

Regarding your question, yes helipcopter drop is fiscal policy. Now providing frns is not helicopter drop because there is no increase in the money supply (see post 3: money supply is what is held by nonbanks)

Providing frns TO BANKS. Plus again fed only supplies to banks on demand.

Hey, don’t sweat editing stuff.

I appreciated the piece overall. I just think that when people talk about helicopter money, they are not literally talking about sending packets of FRNs hurtling through the air. The Social Security Act, for example, provides for millions upon millions of beneficiaries receiving billions upon billions of dollars; none of that is done via FRN airdrop. Rather, helicopter money is a reference to any form of transfer from the government to private actors, FRN, check, ACH, plastic, or other, and unfortunately (or fortunately, depending upon one’s policy preferences) monetary policy has been increasingly tasked with such fiscal implications.

This is the major dogfight, if you’ll pardon mixing of aerial metaphors. In unusual and exigent circumstances (ie, the last 2 decades as the post-Bretton Woods system collapsed), should the Fed (ie, monetary policy) act with a fiscal as well as a monetary role (ie, by handing out below market rate loans, buying assets at above market prices, overlooking criminal behavior, etc.)?

To deny that monetary policy (the Fed) is capable of acting fiscally (as in, transferring public wealth to private actors) is to deny our ability to debate whether it ought to be doing so or not. I don’t think that was a conscious intention, so that’s why my initial question was whether that claim was actually explored.

Right, the Fed can do some fiscal policy operations but not via monetary policy. That was the point of the sentence.

Even in normal time it does some fiscal-operations equivalent, say it buys a building or some computers.

I thought your argument about why we can’t say the Fed printed money was a technical argument based upon FRNs sent to banks, not a semantic one defining the core activities of the Fed as fiscal policy rather than monetary policy.

When people say the Fed printed money, that’s what they’re talking about. Not FRNs given to banks that get recycled through reserves, but rather, non-FRN currency units given to “banks” that result in a net transfer of wealth from the general public to specific financial fraudsters.

I’m with you – to the extent I understand any of this.

Either the big banks got something conjured out of nothing – so why can’t everybody get something conjured out of nothing?

OR

They got something that is reality based. So why is giving “real” money to criminals or idiots or criminals/idiots considered the best use of this real money???

Agreed, well said. I really appreciate how active the author has been in this series and hope this means the more intense discussions here at NC are seeping into the MMT/deficit spending/academic economist thought process.

The real world does not work as neatly as some of the models :-)

I am having a hard time pinpointing where you argument is here.

Fed does not deal directly with the public in its monetary policy operations so it does not influence the money supply. It does influence reserves but not money supply. That is up to the banks.

Let’s put it in a balance sheet form:

Fed can’t do this in its daily operations:

A: Securities L FRNs to Washunate

Fed bought some securities from you paying cash. Note that electronic payment is impossible because you do not have an account at the Fed.

Now the fed buys goods and services from the public (fiscal operations) which lead to this in the Fed bs (say it buys a pizza from you)

A: Pizza L: reserves

and this to bank bs

A: reserve L: account of washunate

Then later you may want some FRNs.

To the extent I have an argument (I generally agree with most of this series), my argument is with your conclusion that the Fed should be bigger and have more responsibilities. I would argue the opposite; the Fed should be a smaller organization with a more limited, more focused scope of activities. I was originally trying to nail down here where I think some of our perspective differs, but through the course of this conversation I have become intrigued by your somewhat conflicting desires to 1) paint the Fed as having strong limits on its monetary policy options, while 2) dismissing critiques of the Fed for circumventing such monetary constraints by acting in a quasi fiscal manner.

I would agree with you that in a narrow definition of monetary policy, the Fed is rather constrained. It exerts influence through incentives rather than absolute control.

But come on, that depends upon academic definitions of money that nobody uses in the wild. At a bigger picture, more general level, Fed actions over the past couple decades have absolutely influenced enormous malinvestment and concentration of wealth and power in our society. To say that people can’t call that phenomenon money printing comes off as trying to deflect criticism of the Fed. If you didn’t intend it that way, that’s cool. Maybe a follow-up post can articulate the language you would prefer on that front? But without such clarification, it sounds like you are trying to prevent criticism of government policy rather than stating that criticism in more precise or formal language.

Maybe it’s getting too much into the weeds…

but when Wash Money Laundering, Inc. becomes a casino (sorry, bank holding company) and the Fed buys my securities for 10% more than market rate, then it becomes a more interesting transaction, both conceptually and in the application of the scenario to what is happening in public policy circles. Indeed, what does the very notion of a market mean when the Fed starts becoming a lender or buyer in size?

Or in accounting terms, it’s not just a swap of cash for securities. It impacts multiple accounts on the general ledger. Because not only did the Fed create enough liability to buy my security, but it also created a liability above and beyond that which goes into my cash account. From my perspective, something like debit cash $110, credit security holdings $100, and credit shareholder equity $10. Thanks for that extra $10! My accounting is a little rusty, but it would be something to that effect.

Sure, from the Fed’s perspective they can simply debit security holdings $110 and credit cash $110. But the asset is only worth $110 because that’s what the Fed paid for it. It created $10 and gave it to me, Control-P style.

If I then go out and buy more houses, either for my personal use or to sell on to the Fed for another $10 in markup, it is true the Fed did not directly control my action. However, the Fed is absolutely responsible for the consequences. But for the actions of the Fed, that $10 wouldn’t exist. It transferred wealth from people buying housing with wages that didn’t get a 10% power-up to WML. Merci beaucoup.

Nice post Washunate!

“At a bigger picture, more general level, Fed actions over the past couple decades have absolutely influenced enormous malinvestment and concentration of wealth and power in our society. To say that people can’t call that phenomenon money printing comes off as trying to deflect criticism of the Fed.”

I agree with you; it seems to me that Eric is showing a little too much deference to the Fed and it’s not clear he knows what he is talking about.

Eric is simply wrong when he suggest that QE didn’t amount to money printing. The Bank of England couldn’t be more clear about this. QE is intended to boost asset prices and translates into a 1:1 increases in bank deposits held by the public. The Bank of England’s explanation can be found here and it’s an easy and informative read.

See page 8: QE – Creating Broad Money Directly With Monetary Policy

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

So we have Eric Tymoigne being directly contradicted by the Bank of England.

An interesting statement from that article is:

” QE works by circumventing the banking sector, aiming to increase private sector spending directly.”

————–

This idea is further explored in this 2012 Bank of England document, http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/qb120402.pdf

“This occurs because the ultimate (non-bank private sector) investors who sell gilts to the APF are likely to view the bank deposits they receive in exchange as a poor substitute for those gilts. As a result, they are likely to reinvest these proceeds into riskier assets that offer a higher return, such as corporate bonds and equities, causing the prices of those assets to rise and their yields to fall.(1) Spending in the economy then rises as companies respond to the lower cost of borrowing in capital markets and both companies and households react to higher asset prices, which increase the value of their financial asset holdings.”

———

They basically describe the central bank as buying securities from the non-bank private sector such as a pension fund using banks as an intermediary. The banks buy the securities/bonds from the pension fund and credit the pension funds account. This new deposit at the bank is backed by reserves from the central bank.

The pension fund can then use their new deposit to fund riskier asset purchases in search of higher yield.

Thank you guys. I see what you mean now and I agree.

Regarding trying to play down problems with the Fed, I did not intend that indeed. The rest of the post shows that I am with you in terms of the problems with the overall response of the Fed during and after the crisis.

I agree that monetary policy seems to be somewhat irrelevant to inequality in the real world, at least in any positive direction of less inequality. It does not seem to be primarily how countries that actually have low inequality seem to achieve it.

‘Fine tuning the economy with interest rates implies raising interest rate during an expansion.’

This is one side of a symmetrical issue.

Yes, the Fed often goes too far or is untimely in raising rates, thus tipping the economy into recession with its ham-handed fine tuning.

Much more perverse, though, is slashing rates during crises. Pre-Fed, overnight rates soared during crises, reflecting lenders’ accurate perceptions of increased default risks. Now during crises, institutions of questionable solvency get subsidized loans, keeping “Too Big To Fail” zombies in business instead of liquidating them.

But of course, this is the raison d’être of the Federal Reserve bank cartel: keeping brain-dead oligopolists like Citibank, JPMorgan and Bank of America in business to rape the public, no matter how corrupt and incompetent their managements may be.

Worse still is that the investment banks Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley have been permitted to pose as commercial banks, despite offering no deposit-taking facility to individuals. Thus the Federal Reserve now subsidizes and protects the high-risk, high-return business of investment banking, a formula for moral hazard if there ever was one.

With their notorious Dec. 2015 policy error — tightening into what looks like a developing global financial crisis — the Federal Reserve has screwed the pooch on an epic scale. Wielding our pens as swords, the best thing we can do is pound the PhD palm readers to a pulp.

As ol’ Wright Patman (my Congressional rep when I wuz in high school) once asked Fed chair Arthur Burns at a banking committee hearing, ‘Can you give me any reason why you should not be in the penitentiary?

Keeping rates low was (and still is) driving a lot of retirees out of safe bonds and into the riskier stock market, against their wills. ZIRP is good for leveraged-to-the-eyeballs stock speculators, but how is it good for anyone else? Maybe the problem with the global and domestic economies isn’t interest rates, but inequality. And the same people who have helped drive the worsening inequality that has led to a mordant global economy, are now whining about losing their cheap money (it’s still cheap, let’s be honest).

Cry me a river. ZIRP never trickled down to us little people in flyover land anyway, so why should we care? I say let’s jack rates up to 5% again so dad can keep his retirement savings in secure bonds, rather than being forced to let somebody gamble with it on the stock market.

ZIRP is a consequence of previous bubble blowing, going back as far as Greenspan’s de facto repeal of reserve requirements in 1994, when the Fed quietly authorized the subterfuge of sweeping demand deposits (which require reserves) into savings deposits (which don’t) overnight.

ZIRP is where we ended up after Bubbles I and II crashed and burned. Now Bubble III is burning like the Hindenburg. Cranking rates to 5% would be one way to liquidate the FIRE sector in one fell swoop. Unfortunately the FIRE sector, with the help of the Federal Reserve, has no intention of being liquidated.

TARP II probably is being drafted as we speak, so that Nancy Pelosi and Co can “pass it to find out what’s in it” after the next crash.

If only you could just liquidate the FIRE sector! If it was possible then I’ve a hunch that someone, somewhere, would have pushed the Big Red Button before now. Either here, in the Eurozone, the BoJ or whatever.

The problem is, interconnectivity dear boy. Slashing and burning, say, Goldman Sachs, would be quite popular. Wildly so perhaps. Razing Gramp’s 401(k) to the ground in the process, maybe less so.

Gramp’s 401(k) is gonna be toast soon anyway, and FIRE will be bailed out again. 401Ks are where they keep the bagholders for Wall Street. Employers only let us move around funds in our 401k at the end of each quarter. So you can’t even go to cash or bonds when the market starts burning down.

Actually, having reasonable low risk short term rates was most peoples shot at some financial democracy. They’ve now pretty much done away with both money markets and low risk bonds as being viable investment areas if you want a little yield – or even just keep up with our phony inflation numbers. So that leaves channeling it all into stock, junk bond and real estate bubbles. And if you leave it in cash, then the banks do it.

Agreed — I was just trying to explain why Jim’s suggestion hadn’t been tried already. It may as you say come to that anyway but hopefully with coordinated fiscal policy action to mitigate as much of the damage as is possible. Either that, or it’s cat food futures.

I hear you Clive on the difficulties. But the author of the post is saying quite explicitly that Fed action doesn’t do anything.

That’s the disconnect here. In real terms, either money printing directs general public resources to specific private actors, or it doesn’t. Either gamblers (sorry, banks) have been reimbursed, in aggregate, by the taxpaying public, or by the currency holding public, or by somebody else holding the bag, or they have not. Either the FIRE sector liquidates, or taxpayers/currency holders pay off the losses.

If Schrodinger got a cat, maybe I’ll start calling this the MMT mouse. There is no way to open the box and find that neither taxpayers, nor currency holders, nor the FIRE sector has been harmed. One of them (at least) has lost purchasing power.

There was a study done that as of end of 2014, ZIRP resulted in a half trillion dollar transfer from savers to banks.

But there wasn’t a big hoopla about it. Savers got no representation.

washunate

February 9, 2016 at 3:11 pm

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++!!!

Also, that is interesting using gramps’ 401(K) as an example. You’re trying to find something that the average citizen can relate to, but even having a meaningful 401(k) balance is uncommon. Sure, there are trillions of dollars in assets in aggregate, but financial asset ownership is extremely concentrated in the US context. Few Americans in the bottom 80% of households have any notable investment in the stock market.

And since older households in America are wealthier overall, it is hard to see how hurting the wealthiest of the wealthiest would rouse ire from the nonwealthy. If anything, that’s a great way of reducing inequaity.

Seriously, in the US, it’s nuts if you haven’t looked at the numbers. The Fed’s survey, for example, has the mean (average) household net worth of those 55-64 at about $795K and for those 65-74 it tops $1 million. The median (midpoint) net worth of households overall is about $81K.

That’s probably mostly in houses – as in they own in full one modest sized house in California maybe.

As in, they own in full one modest sized house in California that they purchased for $60,000 forty years ago.

And they are gonna sell to a millennium w/ 100k of student loans and maybe a job. Or there’s always that rich Chinaman that may happen along.

…. if it doesn’t fall down, first.

++++++

{raises hand and waits politely to be called on}

There is something here I’m not understanding. In Q12 #2, you say the statement, “The Fed injects reserves which lowers the interest rate” is a fallacy. However, in the article that you link to, the process of targeting the FFR is described like this:

The Fed sets the rate and then buys and sell T-bills to effect the amount of reserves in the system, which raises or lowers the rate, depending on whether the FOMC is buying or selling securities. That sounds to me like exactly the same thing you claim here is incorrect. The Fed is watching the FFR and injecting or removing reserves accordingly. However, you say here:

I don’t see how the description above (which was written by the same author) does not have the Fed “proactively” injecting reserves (when the rate starts to rise above the target). How can you claim that the Fed “waits for banks to ask,” when it’s my understanding that the Discount window is almost never actually used by banks, because the FOMC makes sure the Fed Funds market always has enough reserves available.

There is some fine distinction here, but I can’t figure out what it is (apart from the common conflation of “reserves” with “money”). Explanation, anyone?

FWIW, I think you are correct. Although there is a theory out there that the FOMC “follows the market”. But they are driving short rates to their target by adjusting volume of “liquidity”, so that almost sounds like a truism. Also, the author says the Fed transacts with banks. A minor quibble there. They are called the “open market” committee because the trades are open to any broker that has T-bills.

You guys are sitting in the back row and are playing cards, aren’t you? :)

Check post 4, when the fed decides to change its FFRT there is no liquidity effect. So if it wants ffr to be permanently lower it just announces it and then ffr goes there. To maintain a FFRT the fed does inject and remove on demand.

Yes, fed transacts with everybody on fed funds to maintain a supply of funds consistent with FFRT. Check post 4. Here I simplified to banks and reserves.

Not ‘everybody.’ Currently to set a lower bound on the Fed Funds rate corridor using overnight reverse repos, the Fed transacts with over a hundred authorized counterparties.

They are listed here, at the New York Fed website:

https://www.newyorkfed.org/markets/expanded_counterparties.html

Yes, and they took Bank of New York off the list! What is that about?

Thanks. I really need to check that RRP line more carefully

The reason for reverse repo is after all the QE, the Fed has lots more longish bonds in inventory than T-bills, so the math doesn’t work if they only do conventional FOMC transactions because there aren’t enough T-Bills to sell. They didn’t want to sell longish bonds outright, therefore the reverse repo arrangement.

Then there are new T-Bill auctions by the treasury. Only the 19 primary dealers are invited to those. But then they can flip them.

The paying interest on total reserves is new, and that just gives the banks incentive to hold excess reserves at the Fed and out of circulation. Whereas keyboard money that returns to the Fed via RR and FOMC transactions gets the “D” key. That’s short for “Destroy”.

I have a bond broker account at my little bank. I don’t use it because you get crappy prices as a small investor and its cheaper to go the bond fund or money market route. But if I had some scarce T-bills there to sell, I’m pretty sure they would get hoovered up by conventional FOMC outright purchases. Just don’t ask me how they got there.

Thanks for the reply. I was short on time so just skipped to the end, as per Yves’ suggestion. I’ll check out post 4 and see if that helps.

diptherio is correct. POMOs (Permanent Open Market Operations) permanently inject reserves. The Fed (at its initiative, not the dealers’) buys securities from authorized dealers, and credits their accounts with reserves.

QE was simply a giant, preannounced series of POMOs which hiked excess reserves the same way farmers stuff geese with a funnel to make paté.

diptherio

February 9, 2016 at 11:43 am

good reading and nice analysis!!!

Forgive my ignorance, but I don’t see a definitive yes/no answer to question 11. Can someone educate me? Is there a missing closing paragraph?

It is a public institution given that any sector of the economy and anybody can be on the board and fomc. Banks don’t have any say even though they hold stocks. However, today wall street interest is overrepresented (pretty much the same at Treasury though). Remember the expression “Government Sachs”?

I don’t have the specifics off the top of my head but the by-laws of the NY Fed allow the banks to select a number of board members for the NY Fed. The details are pretty outrageous and it is why former Goldman Scum CEO Steven Friedman was a board member and Jamie Dimon at a later date. There was an attempt to change the corporate governance rules for the NY Fed as part of Dodd Frank but I believe it failed.

Are you talking about the directors of each Reserve Bank? Class A and B are elected by member banks, Class C by Board (of governors). Then director elected Reserve bank president, who will sit at the FOMC.

yes the directors and how they are selected.

Ok yep there is some some limited influence from there, especially via class A directors that directly represent banking. Others are supposed to represent other sectors of the economy. Now banks can have some influence through other classes via the former ties of a director (Say now a director works at a car company but was previously at a major bank).

I share the opinion that the Fed is a public institution. I also share the opinion that the Fed is a bank cartel.

““The Fed printed money during the financial crisis”: No it just credited account by keystroking amounts, no Federal Reserve notes were printed. More to the point, none of these funds entered the money supply, i.e. funds held by the public.”

I don’t believe many people think the Fed literally printed money during the financial crisis. Most folks know they “printed” digital credits through keystroke. If the Fed wants to inflate, just keystroke digital credits into every citizen’s bank account instead.

No it did not print money in either fashion, electronically or physically. Money means funds held by the non-banks. The only thing that happened was that the Fed credited electronically the account of bank. So the fed created reserves, not money.

Are “reserves” or “reserves in excess of regulatory requirements” fungible?

Can they be used as collateral for purchases for other assets?

The problem here is that in case of default how would the reserve be transferred? Go back to post 2, there is a limited amount of entities that can receive these reserves.

I’d be interested to see what people think of this group of proposals from David Bollier and Pat Conaty of the Commons Strategies Working Group:

Democratic Money and Capital for the Commons

http://www.geo.coop/story/democratic-money-and-capital-commons-executive-summary

I don’t think they’ve got the MMT memo yet, but they seem to be on the right track. And given the traction these guys get in commons activist circles, I think it would be mutually beneficial for MMT types to get in touch with them.

I guess there will never be anything like a “grass roots reserve” because that would be too effective. it might interfere with the casino…

This is an excellent article and will be much appreciated I’m sure by NC readers.

I believe we can now conclusively agree with Randy Wray that the monetarists’ stuff about the volume of money being important for guiding our economy can be set aside as unworkable theory trying to solve a problem that didn’t really exist.

What does need to be pointed out, especially for prospective occupants of the Oval Office and those seeking to influence the Fed is a point about the fruitless attempt to use monetary policy set by the Fed in steering the economy in any particular direction. Or in having the Fed stimulate the economy or enact any kind of countercyclical balance. FFR, at the end of the day, is guided by answering the question “do we wish to help small savers (with 250,000 or less at stake) stash away money for the purchase of a car, save for the kid’s future college tuition, save for a down payment on a house or a trip to Tahiti?”

Of course Congress, if ever the day were to dawn, could assist in guiding a mass consumer economy in many of these areas, and Bernie Sanders seems to be on to some of what is really needed to have a working, viable economic situation as opposed to the constantly-in-the-ER room situation we have now.

1. Save for future cost of college tuition? Why?, college will be tuition free all the way to a Ph.D.

2. Save for a car? Who will want one when a mass rapid system that includes Rapid Rail will do anything better than our current auto based system.

3. Social Security, disability benefits and jobless benefits would be set at a living wage; say like having the food stamp level for a four person household set at $46k/yr. Save for a rainy day? Not needed as there will be enough raincoats, umbrellas and galoshes to go around. That last is a metaphor, don’t take it too deep.

4. If current income were where it should be for the bottom 90% savings might be relegated to meeting the desires of a few antiquarians.

In short, we have a chattering elite and followers who obsess about the Fed and FFR. Palpitations and heart murmurs begin as soon as the Fed looks one way or another at the FFR. Having said that 0.1% interest rates are idiocy.

O.K. Then.

I exaggerate. There will be some -maybe a lot -who will need to save.

O.K. Yves I skipped to Q.12 in the name of time but will read the entire post later.

with respect to Q. 12 yes there is a lot of confusion about what the fed does, how things work etc. but I have to disagree with point three in Q.12 You are simply wrong when you say that QE doesn’t’ make it’s way into M1.

3. “The Fed printed money during the financial crisis”: No it just credited account by keystroking amounts, no Federal Reserve notes were printed. More to the point, none of these funds entered the money supply, i.e. funds held by the public.

Of course no bloody FRNs were printed by the Fed, I don’t think NC readers aren that stupid. FRN’s are “printed” by a bureau of the treasury department on behalf of the Fed, but that is not the point in any case. When people talk about money printing by the fed it has nothing to do with FRNs. As you explain the Fed simply bought bonds from the banks by crediting the reserve accounts of the banks, an increase in Fed liabilities, and the banks debited their reserve account, an increase in their assets. So far so good, base/high powered money has in fact been created/printed but no broad/M1 money has been created just yet. But it is simply wrong to stop the analysis at this point. Banks are conduits for Fed policy actions. When the Fed swept trillions of dollars of securities off the banking system’s balance sheet and onto its own through QE the banks then moved to replace those securities by buying them from the public, i.e. institutional investors. The banks buy bonds from the likes of PIMCO and other asset managers by simply crediting PIMCO’s deposit account with the bank and VOILA M1 is created/printed from whole clothe in the form of bank deposits. So M1 is in fact created as a consequence of QE and that is precisely what the Fed intended.

If you look at M1 data, there is no spike following QE.

QE proponent wanted banks to increase advance to the public, not to buy securities in the secondary market.

According to the Bank of England you are dead wrong and have it backwards. See page 8 of the following document which basically contradicts all your claims: “QE – creating broad money directly with monetary policy”

http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf

I see that. Yes that can be done. Was not done in the US though where fed went through banks. Mayhe BoE went through that channel, would have to look at the data to see if reserve went up or M1

what are you trying to say? If I read your response correctly your are claiming the “fed went through banks”, meaning the fed bought the bonds form the banks. Well of course they did and that is what the BofE is saying as well, it always goes through that channel. Look, in the late 80s I did a short stint in the treasury department of the 7th largest bank in the U.S.. There was no QE at the time but if the Fed would have come in an swept $100 million of treasuries off our balance sheet in return for some reserves, we would have gone out and replaced those treasuries within 24 hours or we would have been fired. The treasuries paid interest and the reserves don’t so to loose the earnings on $100 million of bonds isn’t tolerable. When we bought the new bonds we would have created deposits at the same time so broad money is “printed” as part of QE.

Dude, what planet are you on? M1 skyrocketed following QE. Just go to the FRED database and type in M1. Unfortunately I can’t paste the graph into this dialogue box so you can see for yourself.

I have generally enjoyed your series but your credibility is suspect at this point. You are an academic economist whose knowledge of money and banking comes from what you have read. And a lot of things you have read happen to be wrong and have little nexus to the real world. That’s why we are in a midst of monetary disaster.

OK, I agree with you. M1 is in post 3 and did go up via NOW and other checkables. I stand corrected.

Thanks by the way. I learned something today!

thank you as well for be willing to say so. I have generally enjoyed your series and have learned from it as well. I have to confess that I have learned a lot over the years from just these types of interactions. The only reason I know anything about money and banking is because I became obsessed with the subject once they started QE and have read ten books on the subject the last few years. The topic is more abstract than people realize and generally not well explained. That why I had to read ten books!

If I may ask, what is your opinion of the following books on money and credit (assuming, of course, that you have read them or know about them):

1) ´Where Does Money Come From?: A Guide to the UK Monetary & Banking System´, by Richard Werner, et al

2) ´The monetary theory of production´, by Augusto Graziani

3) Any of the books by Costas Lapavitsas, such as ´Political Economy of Money and Finance´, ´Social Foundations of Markets, Money and Credit´, ´Financialization in Crisis´, ´Profiting Without Producing: How Finance Exploits Us All´

4) ´Monetary Economics: An Integrated Approach to Credit, Money, Income, Production and Wealth´, by Wynne Godley and Marc Lavoie

5) Any of Michael Hudson´s books, such as ´Finance Capital and its Discontents´, ´The Bubble and Beyond´, ´Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy´, ´Finance as Warfare´

6) Any of the MMT books

Thanks in advance

I haven’t read any of those books but I am awaiting delivery of Michael Hudson’s latest book.

Here is a list of the books I read in the order I read them. There is no rhyme or reason to the list; I just read what I stumbled upon. Unfortunately, there is no one book on the list that explains it all. For me personally, it took a while for all the pieces to click into place and I learned something from all the books.

1. The Mystery of Banking; Murray Rothbard

decent primer on money and banking

2. Money Mischief; Milton Friedman

decent

3. Paper Promises; Phillip Cogan

very good

4. Money: Whence it Came, Where It Went; John Kenneth Gailbraith

very good

5. Money: The Unauthorized Biography; Felix Martin

very good, maybe the most helpful at some level

6. The Battle of Bretton Woods; Benn Steil

very good and helped to frame the current system

7. The Death of Money; James Rickards

very good

8. The Rules of The Game; Kenneth Dam

useful but a very difficult read.

9. Exorbitant Privilege; Barry Eichengreen

very good

10. Reset; Willem Middlekoop

very good

All of the books deal with money and monetary history in one way or another. If you are struggling with the some of the concepts behind money it may be useful to first understand how a gold based system works. For some reason that really helped me, probably because they are less nebulous. I am no gold bug but fiat systems are recipes for abuse and disaster which is where we are at. In any case the one lesson from all the books is that all monetary systems eventually meet their demise. They are man made systems and at some point the issuer always screws them up.

That first book on your list may be good. I read Werner’s article that was the indirect subject of a recent NC post and he knows what he is talking about.

And you thought peer review was tough. :-P

here, try this link, hopefully the M1 graph will come up.

https://research.stlouisfed.org/fred2/graph/?id=M1

Just a note of humor:

Miss Johnson kicked me out of 7th grade history class because she was trying to explain the concept of elastic currency, and I was sitting in the front of the class. In a remarkable display of synchronicity, I happened to have a rubber dollar in my pocket, which I produced and prominently displayed, stretching it for all to see. Miss Johnson was not amused, and I never had a chance to learn the concept. So thank you.

O/T but related: have you read Adair Turner’s new book Between Debt and the Devil, about money, credit and fixing global finance? I’d be interested in any reviews.

On No. 5 on your list. Can banks skirt the system by creating hedgefunds to make sweetheart loans to.

Financial companies always “innovate” to bypass regulations and other constraints.

with respect to Q6, don’t expect any normalization any time soon as in years or decades. The $4 trillion balance sheet is here to stay. That’s why they had to “fake” their Dec-16 interest rate hike by simply declaring they would pay 50 basis points on excess reserves and their reverse repo program. They couldn’t adjust the Fed Funds rate through normal open market operations, not with over $2 trillion in excess reserves in the system so they just declared a new rate in the hopes that someone would believe them.

The entire monetary system is a farce and in it’s death throws. Not clear how it plays out and ends but that is what is happening. ZIRP, NIRP and other idiocies are just signs of badly broken system with no way out.

Promises, promises (from a June 2015 Fed paper):

“Yeah, right!” as the thick-necked ‘traduhs’ at the NY open markets desk say (usually with some expletives appended).

QE1 was gonna be a one-shot deal too. Until QE2 and QE3 were announced.

If they slash the ON RRP floor, rates would clatter back to zero. But maybe that’s the plan. ;-)

“The entire monetary system is …. in its death throes.” If not yet, then one day soon. Given time, every monetary system in existence today will fail, joining history’s ever-growing list of defunct monetary systems. There is no reason to expect the U.S. dollar system to except itself from the historical pattern. Human beings in general, and politicians and bankers in particular, lack the moral compass and tenacity of purpose needed to keep any monetary system on a level basis indefinitely:

If anyone should doubt this, I have a small collection of extinct coinage to offer in evidence. Coins made of iron, coins made of aluminum, coins made of zinc. Worthless now, except to teach the point. Sic transit gloria mundi.

with respect to Q9. Eventually everyone will wake up and realize this is all nuts and that the people running the system are a bunch of clowns who have no idea what they are doing. That has been obvious for some time now but the sheople are slow to catch on. At some point though, and it seems to have started, confidence will be lost and the end game will be commence leading to some form of monetary resent. It’s inevitable at this point but the timing is uncertain. Just keep you fingers crossed it doesn’t lead to chaos, deprivations and war.

It is not just that they are clowns, which they are. I had taken an International Econ class taught by Yellen, and so I know first hand. But it is beyond preposterous that recently insolvent institutions with a continual track record of financial fraud have such special privileges via the Fed.

Beyond preposterous? That recently insolvent institutions with a continual track record of financial fraud have such special privileges via the Fed–is by design. The Fed exists to breathe new life into insolvent institutions, without regard to whether they made themselves insolvent in the honest way.

Which is, absent any accountability, a simple money machine.

I know this a technical discussion long on precise details. I have found that sometimes we focus so much on detail we lose sight of the bigger picture. So I’ll just make a general comment FWIW

IMO if the price of money is zero…. the money has little or no value. It becomes a non-scarce resource.

As managers, our job is to allocate scarce resources, Land, Labor and Capital…

There’s too much capital floating around… We’re throwing it at risky ventures that, were it not for the excess availability, would be passed over for too little RAR… and we wonder why the system is wobbly….

– IMO if the price of money is zero…. the money has little or no value. It becomes a non-scarce resource.

That is a comment worth mulling over, and I shall.

A side note – if by chance it’s you that has given link suggestions I’ve gotten credit for… I fulfilled the Law of Threes by thrice trying to rebalance what may be an autofill issue. Then I stopped. After all, this is America, where taking credit for other peoples labor is a time-honored tradition.

Crap, I just realized, I’ve been taking credit, but the CEO’s take cash. ‘Oh, there’s yer problem…’

{Reply to Steve…}

Re: The Price of Money is Zero If the Republicans are able to get rid of all taxes, then the the demand for the dollar will indeed be zero.

“The Fed printed money during the financial crisis”: No it just credited account by keystroking amounts, no Federal Reserve notes were printed. More to the point, none of these funds entered the money supply, i.e. funds held by the public.

“The Fed used taxpayers’s money during the financial crisis”: No it just credited accounts of banks by keystroking dollar amounts.

this is just nihilism.

The discussion on negative IOR should have been placed in the context of the central banks that are practicing it, not the Fed. Why are the Swiss and the ECB doing it? Why did they have large amounts of excess reserves?