By Andrea Garnero, Economist, OECD Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, Alexander Hijzen, Senior economist, OECD Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs, and Sébastien Martin, Statistician, OECD Directorate for Employment, Labour and Social Affairs. Originally published at VoxEU.

Some economists argue that income inequality suggests intra-generational mobility in society. This column provides comprehensive evidence across a large number of advanced economies on the importance of intra-generational mobility and its relationship with earnings inequality. The findings do not support the belief that higher earnings inequality necessarily goes hand-in-hand with greater mobility over the working life. Higher inequalities are not systematically compensated by higher mobility opportunities.

In many countries, in particular in the US, the perception that inequality has deepened and upward mobility has stalled has become a prominent topic in the political debate (Putnam 2015). While in the past, again especially in the US, inequality was seen by some as the price to pay for upward mobility, this view has become less common as mobility does not appear to have risen in tandem with rising inequality.

Understanding the relationship between inequality and mobility is important for at least two reasons. First, it is crucial for understanding the depth of economic inequalities:

“Consider two societies that have the same annual distribution of income. In one there is great mobility and change so that the position of particular families in the income hierarchy varies widely from year to year. In the other, there is great rigidity so that each family stays in the same position year after year. The one kind of inequality is a sign of dynamic change, social mobility, equality of opportunity; the other, of a status society” (Friedman 1962).

Second, perceptions of mobility play an important role in shaping attitudes to inequality and redistribution and hence preferences for public policies. Alexis De Tocqueville first proposed in Democracy in America the idea that the difference in attitudes towards redistribution between Europe and the US can be explained by differences in mobility rates (De Tocqueville 1835).

A still common line of argument is that inequality is the price to pay for a labour market that offers everyone opportunities commensurate with their talent and effort. This argument suggests that a positive relationship should hold between inequality and mobility, whether mobility is measured between generations (inter-generational mobility) or over the course of one’s working life (intra-generational mobility). However, neither in the context of inter-generational mobility nor in that of intra-generational mobility has this belief been grounded in firm empirical evidence. Indeed, Alan Krueger, in a speech as the Chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors, showed that the relationship between inequality and mobility between generations is negative rather than positive (Krueger 2012). This led him to dub this relationship the ‘Great Gatsby curve’, in an ironic reference to the character who rises ‘from the rags to riches’ in F Scott Fitzgerald’s classic novel. The existing empirical studies on the relationship between inequality and intra-generational mobility have yielded mixed results at best, but these studies have been limited to the US and one or a few European countries and thus may not tell the full story.

In new research, we provide for the first time comprehensive evidence across a large number of advanced economies on the importance of intra-generational mobility and its relationship with earnings inequality (Garnero et al. 2016). It does so by adapting and extending the simulation methodology proposed by Bowlus and Robin (2012) to generate individual earnings and employment trajectories in the longer term using short panel data for 24 OECD countries. A validation exercise using social security data for Italy shows that this approach captures the observed evolution of earnings and, particularly, the degree of mobility rather well. Our analysis provides a number of important insights:

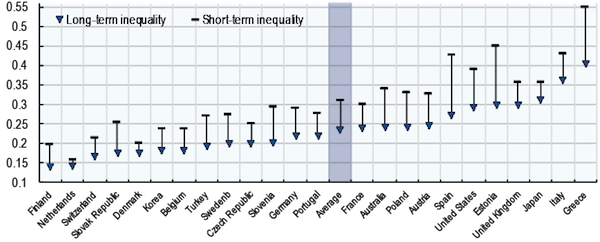

- First, on average across the countries analysed, mobility (i.e. movements up and down the wage ladder and in and out employment) reduces inequality, as measured by the Gini index, by about 25% over the first 20 years of careers (see Figure 1).

Since the bulk of mobility occurs during the first 15 years of one’s career, this implies that approximately 75% of inequality within a year is permanent.

Figure 1. The equalising effect of mobility

Source: Author’s calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) for European countries and Turkey, Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) for Australia, German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) for Germany, Keio Household Panel Survey (KHPS) for Japan, Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS) for Korea, Swiss Household Panel (SHP) for Switzerland and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for the United States.

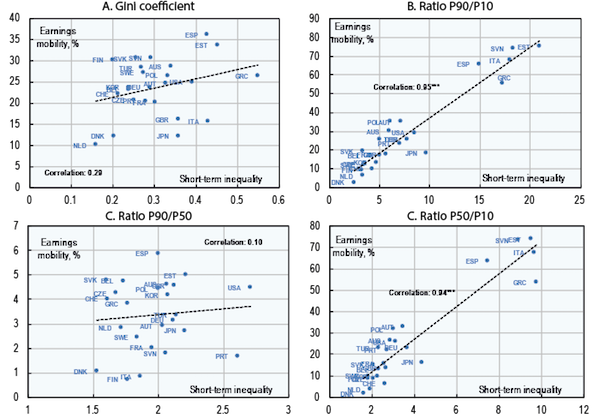

- Second, the cross-country correlation between mobility and inequality at a point in time tends to be weak and depends on the measure of inequality used (see Figure 2).

This means that the belief that higher inequality is compensated by higher mobility is not validated – only when using inequality indices focusing on the tails of the distribution (for example, the P90/P10 and P50/P10 percentile ratios) the relationship between inequality and mobility is strongly significant and positive while this is not the case when using indices considering the entire distribution (for instance, the Gini index).

Figure 2. Correlation between mobility and inequality, active persons

Source: Author’s calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) for European countries and Turkey, Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) for Australia, German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) for Germany, Keio Household Panel Survey (KHPS) for Japan, Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS) for Korea, Swiss Household Panel (SHP) for Switzerland and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for the US.

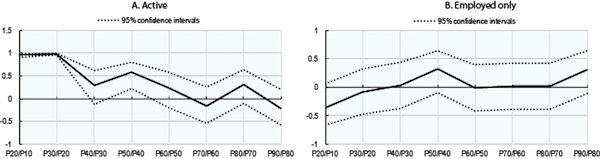

- Third, when looking at the relationship between mobility and inequality along the entire earnings distribution, we find that any positive relationship between inequality and mobility is driven by the relationship between inequality in the bottom of the distribution (Figure 3, Panel A).

Moreover, the positive correlation between earnings mobility and short-term inequality across countries disappears when considering only individual who are continuously employed (Figure, Panel B). This suggests that the positive relationship between mobility and inequality in the bottom of the distribution is driven by movements between employment and unemployment and not mobility up and down the earnings ladder.

Figure 3. The correlation between inequality and mobility along the distribution

Source: Author’s calculations based on the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) for European countries and Turkey, Household, Income and Labour Dynamics (HILDA) for Australia, German Socio-Economic Panel (GSOEP) for Germany, Keio Household Panel Survey (KHPS) for Japan, Korean Labor and Income Panel Study (KLIPS) for Korea, Swiss Household Panel (SHP) for Switzerland and Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) for the United States.

In conclusion, our findings do not support the belief that higher earnings inequality goes necessarily hand-in-hand with greater mobility over the working life. Higher inequalities are not systematically compensated by higher mobility opportunities. There is no negative correlation as in the context of inequality and mobility across generations, but neither a positive relationship as many, especially in the Anglo-Saxon world, appear to believe. This means that policies and institutions can yield different combinations of inequality and mobility.

The positive relationship between inequality in the bottom of the distribution and employment mobility (movements in and out of employment) most likely reflects the role of policies and institutions for wage compression in the bottom of the distribution and employment mobility. Policies and institutions such as unemployment benefits, statutory minimum wages and collective wage agreements effectively impose wage floors and, as a result, have a tendency to lead to a more compressed wage distribution. In doing so, these institutions also make it harder for individuals to escape unemployment and hence reduce employment mobility. In countries where such institutions are weak, unemployed workers may find jobs more easily but these jobs tend to be less well paid and less secure since due to the weaker bargaining position of unemployed persons.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and cannot be attributed to the OECD or its member countries.

References

Bowlus, A and J-M Robin (2012), “An International Comparison Of Lifetime Inequality: How Continental Europe Resembles North America”, Journal of the European Economic Association 10(6): 1236-1262.

De Tocqueville, A (1835), De la démocratie en Amérique, Éditions Gallimard.

Friedman, M (1962), Capitalism and Freedom, University of Chicago Press.

Garnero, A, A Hijzen and S Martin (2016), “More unequal, but more mobile? Earnings inequality and mobility in OECD countries”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers No. 177.

Krueger, A (2012), “The Rise and Consequences of Inequality”, Speech at the Center for American Progress, 12 January (2012).

Putnam, R (2015), Our Kids: The American Dream in Crisis, Simon and Schuster.

Use economics that doesn’t make an important distinction and watch inequality rise.

It is baked into the cake of today’s economics.

Adam Smith:

“The Labour and time of the poor is in civilised countries sacrificed to the maintaining of the rich in ease and luxury. The Landlord is maintained in idleness and luxury by the labour of his tenants. The moneyed man is supported by his extractions from the industrious merchant and the needy who are obliged to support him in ease by a return for the use of his money. But every savage has the full fruits of his own labours; there are no landlords, no usurers and no tax gatherers.”

Like most classical economists he differentiated between “earned” and “unearned” wealth and noted how the wealthy maintained themselves in idleness and luxury via “unearned”, rentier income from their land and capital.

We can no longer see the difference between the productive side of the economy and the unproductive, parasitic, rentier side. This is probably why inequality is rising so fast, the mechanisms by which the system looks after those at the top are now hidden from us.

All rentier activity is detrimental to the productive parts of the economy, siphoning off prospective purchasing power to those that like to sit on their behinds.

If we were still able to recognise the difference between “earned and” “unearned” wealth we might realise that encouraging rising prices of stuff that exists already is not very productive, e.g. housing booms.

Same houses, higher prices, higher mortgages and rents, less purchasing power

As the rentier economy booms, rents and interest repayments on debt escalate and purchasing power goes down leading to the current debt, deflation.

Michael Hudson – Killing the Host

Capitalism is an old system designed to maintain a Leisure Class at the top.

Every social system since the dawn of civilization has been set up to support a Leisure Class at the top who are maintained in luxury and leisure through the economically productive, hard work of the middle and lower classes.

The lower class does the manual work; the middle class does the administrative and managerial work and the upper class lives a life of luxury and leisure.

(The Theory of the Leisure Class: An Economic Study of Institutions, by Thorstein Veblen.

The Wikipedia entry gives a good insight. It was written a long time ago but much of it is as true today as it was then. This is the source of the term conspicuous consumption.)

In the UK we call our Leisure Class the Aristocracy and they have been doing very little for centuries.

The UK’s aristocracy has seen social systems come and go, but they all provide a life of luxury and leisure and with someone else doing all the work.

Feudalism – exploit the masses through land ownership

Capitalism – exploit the masses through wealth (Capital)

Today this is done through the parasitic, rentier trickle up of Capitalism:

a) Those with excess capital invest it and collect interest, dividends and rent.

b) Those with insufficient capital borrow money and pay interest and rent.

The system itself provides for the idle rich and always has done from the first civilisations right up to the 21st Century.

The mechanism that looks after the Leisure Class has been hidden in today’s economics, it was identified centuries ago by the Classical economists and they called it “unearned” income.

Today we pretend it doesn’t exist and watch inequality rise, with seemingly no idea why.

We need to get out some old books.

How much longer can we carry on believing in the weird science?

Neo-Liberal Economics – The Weird Science

In 2008 the world economy suffered the biggest economic shock known in the history of mankind; the weird science attributed it to a mythical creature, “the black swan”.

In times past we used to attribute eclipses to mythical creatures swallowing the sun, but real science has moved on.

The weird science governing the global economy has been trying unconventional solutions since 2008 to try and get things back on track. When the problem was caused by a mythical creature, “the black swan”, these are the only solutions available. These unconventional solutions, or “stabs in the dark” as they are technically known within the weird science, are not having a great deal of success.

The Neo-Liberal, “weird science”, has been rolled out across the world and it is the only version of economics now taught in Universities around the world.

No economic history is now taught so the students don’t see different ways of thinking and don’t question Neo-Liberal economics.

Neo-Liberal economics is right and should not be questioned within any mainstream institutions.

Students must concentrate on building complex mathematical models on the base of the Neo-Liberal, economic model, it is right and cannot be questioned. The only way is up, building on these foundations.

To believe in Neo-Liberal economics you have to believe in the mythical creature, “the black swan”, which explains the major events that occur outside of your belief set.

Neo-Liberal economics it’s weird science.

For devotees of Neo-Liberal economics, “the weird science”, prepare for a shock.

Some economic history outside the carefully selected version you have been bought up on.

Malthus and Ricardo never saw those at the bottom rising out of a bare subsistence living. This was the way it had always been and always would be, the benefits of the system only accrue to those at the top.

The benefits of the industrial revolution did accrue to those at the top in 19th Century England and they were fabulously wealthy. Those at the bottom lived a life of bare subsistence, though now through meagre wages rather than what they produced themselves.

It took the ideas of Marx, and collective labour movements, to prise some of the benefits away from those at the top to those at the bottom. Though those at the top were still fabulously wealthy and those at the bottom lived a miserable existence, but slightly better than it had been before.

By the 1920s, mass production techniques had improved to such an extent that relatively wealthy consumers were required to purchase all the output the system could produce and extensive advertising was required to manufacture demand for the chronic over-supply the Capitalist system could produce.

A system bringing prosperity to all was now in place and relatively wealthy consumers were required to keep the profits flowing to the top in ever larger quantities.

Capitalism was never designed to bring prosperity to all it is designed to look after those at the top.

By coincidence it did bring some prosperity to those at the bottom through the efficiency of mass production.

The Neo-Liberal class war is now destroying demand, the consumer society and the system itself.

“There’s class warfare, all right, but it’s my class, the rich class, that’s making war, and we’re winning.” Warren Buffett

The 1% went to war on the 99% (aka the global consumer), very silly really.

We are led to believe Capitalism and the private sector are efficient.

Private luxury and public squalor.

John Kenneth Galbraith captures the 1950s American Dream in “The Affluent Society”

“The family which takes its mauve an cerise, air-conditioned, power-steered and power-braked automobile out for a tour passes through cities that are badly paved, made hideous by litter, lighted buildings, billboards and posts for wires that should long since have been put underground. They pass on into countryside that has been rendered largely invisible by commercial art. (The goods which the latter advertise have an absolute priority in our value system. Such aesthetic considerations as a view of the countryside accordingly come second. On such matters we are consistent.) They picnic on exquisitely packaged food from a portable icebox by a polluted stream and go on to spend the night at a park which is a menace to public health and morals. Just before dozing off on an air mattress, beneath a nylon tent, amid the stench of decaying refuse, they may reflect vaguely on the curious unevenness of their blessings. Is this, indeed, the American genius?”

The UK consumer, bamboozled by yet more advertising and marketing campaigns, gets home with their new products to find there is no room for it in their house.

They have to clear out some old stuff and put it into storage to make room.

The nation is now covered in storage units housing the surplus products from the private sector.

Perhaps it is time to start spending more on the NHS, schools, GP surgeries, public spaces, public services, the disabled, the under priveledged, etc ……. rather than covering the nation with storage units to house the surplus output of the private sector that we cannot fit within our homes.

An efficient use of the world’s resources?

I think not.

The private sector could be efficient if it manufactured what people wanted rather than manufacturing demand for things people don’t really want with advertising and marketing.

It’s just a matter of category and definition. VERY efficient trashing of the planet and wealth and ownership concentration, after all…

‘All rentier activity is detrimental to the productive parts of the economy, siphoning off prospective purchasing power to those that like to sit on their behinds.’

Rubbish. Today there are no returns on being a rentier (thanks to ZIRP). And this statement doesn’t correctly characterize the essentially businesslike character of many rentier situations. For instance, if you rent property for a living, you realize that you’re taking a risk–a potential tenant may tear it up; and if they are poor, you have no recourse. And they may not pay you. If you stop offering your property to the market for rental, you do your part to drive up rents in the market as a whole. Being a rentier isn’t all it’s cracked up to be, but it is a service to society.

Untouchables in caste systems have no income mobility and are about as income unequal as you can get.

Good on’em for doing the study. It’s amazing to me it needed to be done on an issue that could have been debunked categorically.

Yup, glad to know people are devoting the precious and fleeting hours of their lives to disproving obvious BS.

And some economist suggest that people must really like being homeless, since so many are doing it, and we know that everyone maximizes their personal utility.

And don’t forget how so many folks developed a stronger preference for leisure over work in 2008. There still seems to be some residual (age-related), though recent references to la-di-dah vacationing of the disemployed are scarce.

“In many countries, in particular in the US, the perception that inequality has deepened and upward mobility has stalled has become a prominent topic in the political debate…”

They didn’t look at Mexico, birthplace of the richest man on Earth, Carlos Slim? Why he just immigtrated to the USA, after becoming the largest individual shareholder on the NYT. Of course the 10,000,000 or so other Mexicans who came North recently have the other half of the income “inequality”. I wonder who is going to do something about that? Maybe the Mexican government (the govt. whose privatization of TelMex made Carlos Slim so unequally wealthy)?

avoid tiresome bills and home repairs, move up to a large cardboard carton today and simplify your life.

It’s good to see discussion about inequality within the context of establishment economics, but I think it is worth gently noting that this is some pretty weak tea outside the econ bubble. The very construct of the argument sets aside issues like the legal system and the healthcare system when those differences are some of the biggest sources of inequality. One of the huge outliers of the US in particular is that we run the largest prison and healthcare systems in the OECD, both of which are massively unevenly and non-randomly distributed in their access and consequences.

For example, from SIPP (bold mine):

Productivity cannot be measured, and energy is a hoax. Breaking that carbon bond after plant life is decimated and those carbons are sitting under a desert in a reservoir is not a future. Healthcare is a function of elastic synaptic response in a ribosome medium, which means natural childbirth, breastfeeding and free associative playing. Math, language and cultural mythology is a derivative outcome, public education fitting people into arbitrary RE control, chasing machines. You kids are far better off at the library, because librarians aren’t hired to enforce RE bigotry.

Measuring physical mobility is a waste of time, because the mobility you want is a function of productive imagination, intuition, which cannot be measured by the Fed measuring the product of self-serving psychologists, and is therefore no longer valued in our society. The biggest mistake we made was letting the psychologists on school grounds back in the 60s. Whatever the answer proves to be, it will not be drugs.

The price of drugs is only relevant in a gas chamber. RE does not value people. It’s a counterweight most are chasing into the pit.

Transcription is not a one way street.