\We’ve criticized CalPERS for sticking with investment strategies long past their sell-by date. Our very first post, in December 2006, pointed out that CalPERS had admitted that it wasn’t getting adequate performance from hedge funds. Yet CalPERS rationalized sticking with these managers because they supposedly provided useful portfolio diversification. But that argument was also bogus, since CalPERS could have created similar return profiles for vastly lower fees than the “2 and 20” it was paying to hedge fund managers. It took CalPERS a full eight years to act on this information and exit hedge funds….save ones that offered low-fee “alternative beta”.

CalPERS and other limited partners have been even more reluctant to kick the private equity habit. The big reason, as CalPERS’ staff has repeatedly said, is that they believe that private equity is their potential knight in shining armor as far as enabling them to meet their overall portfolio return target of 7.5% is concerned. But that belief is based on the bogus logic of regarding past performance as a predictor of future results, even when the top player in the industry, who have every incentive to sell hope, are warning that returns in the future will be lower than in recent years. And those results haven’t been impressive.

One indicator of the declining standing of private equity is that even its most successful investors are no longer able to achieve superior results by relying on high leverage, high risk “alternative investment” strategies like private equity and hedge funds. What may have looked like genius might instead have been luck. After Volcker broke the back of inflation in 1982, the US was on a long-term trend of disinflation and declining bond yields. Where do you want to be when return requirements are falling? In risky assets. More specifically. strategies that normally look like walking on the wild side, such as levered investments in risky assets, can deliver particularly juicy payoffs.

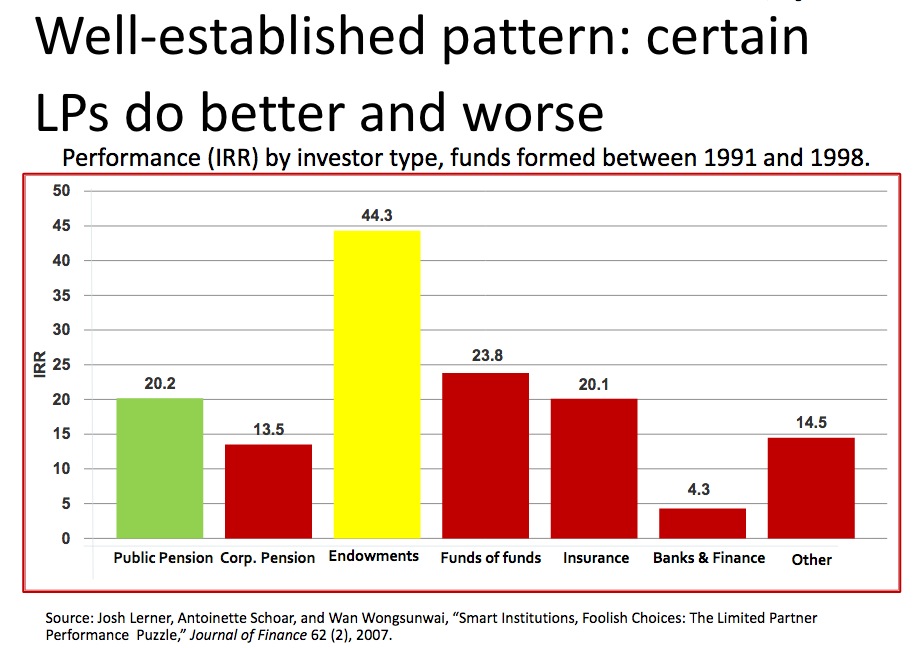

Endowments like Yale and Harvard, which hired “talented” staff, paid them well, and allowed them to make exotic investments, were widely seen as the smart long term investors. And in the heyday of private equity investing, in the mid 1990s, they lived up to their glitzy image. Fromm Harvard professor Josh Lerner’s presentation at CalPERS’ private equity workshop last November:

But endowments generally stopped living up to their reputation. As Lerner noted later:

• Sensoy, Wang, and Weisbach (2013) find that endowments no longer outperformed other LPs from 1999 to 2006.

• In fact, the authors found no statistically or economically significant differences in returns across LP types.

• During this period, reinvestment decisions of endowments were not statistically unusual relative to other institutional investors.

And even the much-touted Yale’s long-term performance isn’t a model for other investors. Its returns depended on its heavy allocation to venture capital. And not just any venture capital…but investments in Chinese venture funds that it identified through its alumni network. Other investors, even most other universities, lacked this information advantage. And returns from Chinese investment benefitted from the appreciation of its currency and its WTO entry in 2002, powerful tail winds that are no longer in play.

A Bloomberg story describes how even these supposedly super-savvy experts in illiquid investments would have done better with a straight up mix of good old fashioned stocks and bonds:

According to numbers compiled by Wilshire Trust Universe Comparison Service (which tracks endowments’ investment performance), the median return for endowments greater than $500 million trailed a 60/40 U.S. portfolio by 0.9 percent annually over five years through June 2015. And the median endowment return over ten years was just 7 percent annually – a mere 0.2 percent annually better than a 60/40 portfolio.

There is nothing unusual — or even concerning — about cyclical periods of low returns, but the problem may be more deep-seated. The Harvard endowment’s rolling ten-year returns have been trending down ever since HMC’s first decade at the helm ended in June 1983. Harvard’s ten-year returns peaked 16 years ago, and since 2009 the endowment has struggled to achieve a ten-year return that numbers in the double-digits.

The so-called endowment model of investing…calls for greater investment in private assets and hedge funds and less reliance on traditional investments such as stocks and bonds.The endowment model worked wonders for a while because private equity and hedge funds posted astonishing returns.

The HFRI Fund Weighted Composite Index – a widely followed gauge of hedge fund performance – returned 18.3 percent annually during its first decade from 1990 to 1999. Private equity did even better. Cambridge Associates’ U.S. Private Equity Index returned 20.4 percent annually over that period.

More specifically, the real glory years for private equity were from 1995 to 1999. That was due to a rebund after private equity and even M&A fell out of favor after the nasty early 1990s recession. As those boom years roll out of long-term comparisons, the data no longer supports the story of private equity being a “gotta be there” strategy.

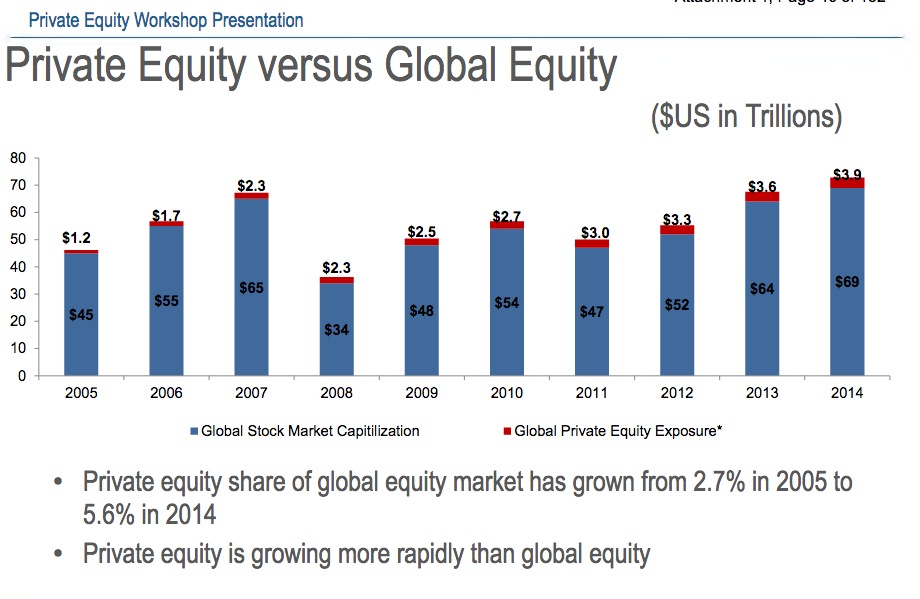

Part of the problem is too much money chasing (comparatively) too few deals. We highlighted this slide, again from the CalPERS November private equity workshop:

The Bloomberg article tells a similar story:

According to Wilshire, the median allocation to private equity and hedge funds and other alternative investments among endowments greater than $500 million was a paltry 14.6 percent in June 2005. That number swelled to 49.2 percent by June 2015.

The popularity of private equity and hedge funds among endowments has mirrored the explosion of interest in those investments more generally. According to HFR, hedge funds grew from $39 billion under management in 1990 to nearly $3 trillion in 2015. Private equity saw similar growth. According to Preqin, private equity grew from $580 billion in 2000 to $2.4 trillion in June 2015.

ELUSIVE ALPHANothing squashes investment returns like a stampeding herd of investors.

And it reaches a damning conclusion:

Using the simplest measure of risk-adjusted returns – a ratio of annual return over standard deviation — both the Harvard endowment and a 60/40 U.S. portfolio achieved exactly the same ratio of 0.97 from July 1973 to June 2015. (Standard deviation measures the volatility of an investment and is a commonly-used proxy for risk.)

In reality, Harvard’s risk-adjusted return is likely even worse. Harvard’s private assets aren’t subject to the daily gyrations of public markets, so their volatility is understated.

If those results are the best that Harvard could achieve in the golden age of private equity and hedge funds, it’s unlikely to do any better with those investments going forward. And it could do worse because the combination of high fees and crowded trades have become formidable headwinds for private equity and hedge funds. Private equity and hedge funds also often rely on leverage — an advantage that may disappear as banks grow more conservative about exposure to outsize risks — and rock-bottom interest rates won’t stay so low forever.

The article argues that it still might be worth investing in private equity and other alternative assets for diversification. But that argument not longer holds up either. As we said earlier, investors can obtain so-called synthetic or alternative beta at vastly lower cost than hedge fund manager fees. And private equity offers very little real diversification. Private equity returns have become more highly correlated with stock market averages since the crisis. And that’s before you get to the openly-acknowledged fact that much of what apparent diversification there is is the result of bogus accounting, of not marking portfolio values down much in bear markets, when generally speaking, levered equity should fall even further than listed stocks.

And CalPERS has additional reasons for staying away from private equity. Its former CEO is in prison as the direct result of private equity pay to play. Pension funds all over the US continue to be embroiled in scandals involving payoffs and questionable political payoff from alternative investment managers. In the eyes of the public, CalPERS’ refusal to take on private equity bad practices or even genuinely support transparency measures like California’s AB 2833 look like more corruption, as opposed to intellectual capture. And CalPERS is providing the rope that is being used to hang it by investing in private equity. Private equity investors routinely seek to break unions and terminate pension plans, and the erosion of private sector worker rights and retirement benefits make public sector plans look like indefensible largesse. Similarly, the headcount and other cost cutting these funds engage in lowers employment and pay levels. Those hurt state and local economies, and hence their tax revenues, making it relatively more expensive to fund public pension fund contributions.

CalPERS and its fellow public pension funds mistakenly treat private equity general partners as important allies. In fact, the general partners regard them as particularly easy sheep to shear. The sooner CalPERS and its ilk smarten up. the better.

Thanks for the great post Yves. Interestingly enough, Massachusetts just broke out it’s 10 year portfolio performance metrics for their public pension funds and private equity was the leading return generator, though they split hedge funds and PE into different categories.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-08-09/hedge-funds-make-last-place-at-61-billion-massachusetts-pension

The overall story is state pension authorities souring on hedge funds as an investment class, but the figure embedded in the article would lead one to believe that at least for Massachusetts, PE is a great part of the portfolio. No indication on if that return is net after fees etc.

Standard practice in the industry is that any PE return is communicated net of all fees, especially when it comes form LPs.

Where does the information about Yale and Chinese VC comes from? What is the source?

Members of the Yale team said that in response to questions at the last CII conference.

There are only 3000 public companies left outside otcmarkets.Of course pe firms could trade companies between themselves to keep their values inflated….

Google says “under 4000”. And that’s very liquid ones in the US only.

So? You only need 20 to be diversified, 50 if you want to be conservative about it. I know a hedge fund with a very unusual investment strategy (its returns really are highly differentiated from that of other fund managers) and its investable universe is only 450 companies.

I found your comment on PE trading with each other to prop up values quite interesting. An offer for PE company Autotrader Canada by another PE company looked much higher than a lot of Interested people thought would provide a reasonable ROI. Your comment makes sense of the transaction.

Thanks as always for very interesting and insightful information. IF ONLY CalPers was listening, learning and changing. IF ONLY.

Who’s buying off the CalPers Board? Cui bono from PE investments?? Inquiring minds need to know.

Wow, this could be more evidence of private equity malfeasance. Would they really do something like this story claims? Probably.Alot of people would so why should they be any different? Maybe because they’re more inclined to be slaves of their passions?

This is pretty incredible reporting though, you wouldn’t see this in the New York Times, that’s for sure/ Or the FT. Gilian Tett could never scoop a story like this!

The Long Arm of Private Equity

A Worldwide News Service Exclusive

by Delerious T. Tremens, Reporter at Large

August 11, 2016

New York (WNN) – When 25-year-old legal assistant and part-time stripper Amber Hott moved into Nirvana on New Yoark’s Upper West Side, she was ready for almost any adventure her self-described “City of Dreams” could offer. Owned and managed by prestigious private equity firm Grabbin Hand, the Nirvana was a dream come true — a luxury designer-inspired high-rise residence featuring amenities such as personal trainers, a spa and, rooftop lounge with bar and restaurant, concierge, personal assistants and a neighbors who formed the young elite of Manhattan’s upscale social whirl. The Nirvana even eschews the pedestrian word “tenants” to describe residents, instead elevating their status through the grander phrase “limited partners”. But when Ms. Hott describes the lurid events of a morning in April, Grabbin Hand takes on a new and decidedly sinister connotation.

“I was in the bathroom” Ms. Hott tells a reporter, “and an arm came up through the toilet bowl and . . . it was awful, it was so horrible” Ms. Hott broke down into tears but her lawyer, Seymour Sharp of Sharp and Sharp, finished her sentence. “My client was assaulted by a Grabbin Hand “facilitator” and her sphincter was penetrated while she sat on the toilet,” says Mr. Sharp. “She was forcibly penetrated by the end of a tightly rolled limited partner contract in a lurid effort to collect her rent.”

Jim “Jimbo” Grabbin, founder and CEO of Grabbin Hand vigorously denies the allegations. Jumping up to greet a reporter Mr. Grabbin, a giant of a man, extends a large fleshy hand in an enthusiastic pumping welcome in his cathedral like office 49 floors above Manhattan’s Park Avenue with sweeping 360 degree views of Ms. Hott’s city of dreams. “I don’t know the particulars,” he said on the record, “but all limited partners agree to abide by facilitation procedures, which include nudges to prompt financial compliance with contract terms.” These nudges, according to WNN investigation, can involve access to what the contract describes as “limited partner premises exclusively for incenting compliance with contract terms in a discreet and non-threatening manner.” Mr. Grabbin insists that the “nudge” received by Ms. Hott was well within the scope of the contract and he denies that her sphincter was penetrated. “Our facilitators are professionals, respectful and well-trained” he insisted.

What Mr. Grabbin did not deny and which he refused to discuss was just how an arm could have reached up through a toilet bowl while Ms. Hott was attending to her morning hygiene. But a WNN investigation found that toilets installed in Nirvana residences are far from typical.

“This ain’t like no john I ever saw,” said Billy Blake, a Tenessee born and now New York licensed plumber hired by WNN as an investigative consultant. “Looky there, them’s two holes in the bowl not one.” he said, pointing at the bowl where Ms. Hott alleges an arm extended, “Them’s where an arm can stick through. Shit Fart I ain’t never seen nuttin like that nowhere bit here. Bunch of perverts if you ask me.” WNN investigation further revealed that Nirvana building plans include a crawl space between floors where facilitators access apartments to nudge limited partners.

A WNN investigation discovered that Hose Rameirez Cortez, a 4′ 9″ tall and 120 pound 19 year old Guatemalan resident is the alleged penetrator, but penetrating Ms. Hott’s sphincter is an act Mr. Cortez denies. While he admits laying in the crawl space between floor and waiting for Ms. Hott to enter the bathroom, he says he had no ability to visually aim the contract. “I attempted to perform my duty to my employer” he says through an interpreter, “with dignity and responsibility. I felt a resistance to the end of the contract, but it felt to me like I encountered a curvature, it did not seem to me to be a hole. The ends of the paper, they were not grabbed, they were not grabbed in the manner in which one would expect if a hole had been penetrated.”

When asked why not just knock on doors and remind limited partners to pay rent, Grabbin Hand CEO Linda Hand, a thin and athletic blonde with an aristocratic poised demeanor, tells a reporter that would be “too aggressive”. “Our limited partners value discretion. A face to face encounter is confrontational and threatening” according to Ms. Hand. “These are sophisticated New Yorkers. They understand contract terms. they understand business. It may be Ms. Hott is unsophisticated and probably should live somewhere else while she matures.”

For he part, Ms. Hand’s ascent to the pinnacle of the private equity business was anything but conventional. As a young analyst at Grabbin Hand she, herself, filed a sexual harassment lawsuit against Mr. Grabbin. Court records show Mr. Grabbin vigorously refuted the allegations, he was quoted as saying “I wouldn’t fu-k that bitch if I was on Viagra.” But Ms. Hand was nevertheless made senior partner and then co-CEO after a series of backroom negotiations. “She’s tenancious” says Mr. Grabbin now to a reporter, “you can’t take that away from her. She may rub you the wrong way but you can’t underestimate her. She’s done a good job overall, in her current role.”

Ms. Hand remains skeptical about Ms. Hott’s claims. Ms. Hott refuses to submit the rent contract for lab tests that could determine whether sphincter penetration occurred. When asked why, Ms. Hott’s legal team refers to the hygiene standards required of strippers. “There’s no question penetration occurred but lab tests won’t reveal any evidence,” says her attorney Mr. Sharp. “My client is clean. The penetration occurred and was emotionally traumatizing. We don’t need tests to prove it.”

That doesn’t persuade Ms. Hand. “Amber wants a job and this is extortion” said Ms. Hand to WNN. “She ambitious, cunning and willing to lie. She doesn’t want a career as a stripper, she wants to be a partner here.”

Ms. Hott rubs away tears and turns a reporter’s questions over to her lawyer. Mr. Sharp is circumspect about Amber’s future, “Like many young New Yorkers, she’s looking to live her dream. She thought she’d find it at Nirvana, but she was violated. If there’s a better opportunity in her future, we’re prepared to negotiate. We won’t hold a grudge.”

Get me the eff out of Moderation. I’m trying to report here on a private equity scandal! This is a Wordwide News Service exclusive.

I’m trying to think how CalPERS and others would respond to a sales pitch that starts out, ” Sixteen years ago this investment strategy was the best. Not so much lately, but sixteen years ago, 20 years ago, it was the best.”

Great post.