By Lynn Parramore, Senior Research Analyst at the Institute for New Economic Thinking. Originally published at the Institute for New Economic Thinking website

Outrage over how big money influences American politics has been boiling over this political season, energizing the campaigns of GOP nominee Donald Trump and former Democratic candidate Sen. Bernie Sanders alike. Citizens have long suspected that “We the People” increasingly means “We the Rich” at election time.

Yet surprisingly, two generations of social scientists have insisted that wallets don’t matter that much in American politics. Elections are really about giving the people what they want. Money, they claim, has negligible impact on elections.

That was a good line for Cold War propaganda, and good for tenure, too. Corporate titans seized upon it to argue that their money should be freer to flow into political campaigns. Not only billionaires, but academics, too, argued that more money in elections meant more democracy.

Even today, many academics and pundits still insist that money matters less to political outcomes than ordinary citizens think, even as business executives throw down mind-boggling sums to dine with politicians and Super Pacs spring up like mushrooms. The few dissenters from this consensus, like Noam Chomsky, are ignored in the U.S. as “unpersons,” though they are enormously respected abroad.

This is a scandal. It has stymied efforts at campaign finance reform and weakened American democracy.

Political scientist Thomas Ferguson, Director of Research at the Institute for New Economic Thinking (INET), has spent a career setting the record straight with clear empirical evidence in a field where such research has been shockingly rare. Ever since his 1995 book Golden Rule: The Investment Theory of Party Competition blasted through received academic wisdom by showing how wealthy individuals and businesses strategically invest in political parties for the biggest pay off, Ferguson has been the man to seek when you really wanted to know how elections work and who controls them.

White collar criminologist William K. Black and others still recall Ferguson’s famous warning, issued long before the nominating convention in 2008, that the contributions from big finance piling up in Barack Obama’s campaign war chest meant that his promises of sweeping reforms of finance were not to be believed. In 2014, he foresaw the unraveling of America’s two major political parties and predicted that voters feeling betrayed would increasingly abandon both.

“Want a happy ending?” he quips. “See a Disney movie.”

In recent years, Ferguson has often worked with two other talented researchers, Paul Jorgensen and Jie Chen. The three have tracked the generous funding of Obama by high tech businesses engaged in spying on the American public and the waves of money from polluters into the Republican Party.

Spend Money, Win Votes

Now the researchers have turned their attention on political money in Congressional elections in a new paper for (INET).

They begin with a simple question: What are the facts about total campaign spending and election outcomes? As they write: “We can pool all spending by and on behalf of candidates and then examine whether relative, not absolute, differences in total outlays are related” to the differences in votes received by the major political parties.

Their answer is stunning: there is strong, direct link between what the major political parties spend and the percentage of votes they win – far stronger than all the airy dismissals of the role of money in elections would ever lead you to think, and certainly stronger than anything you read in your poli sci class.

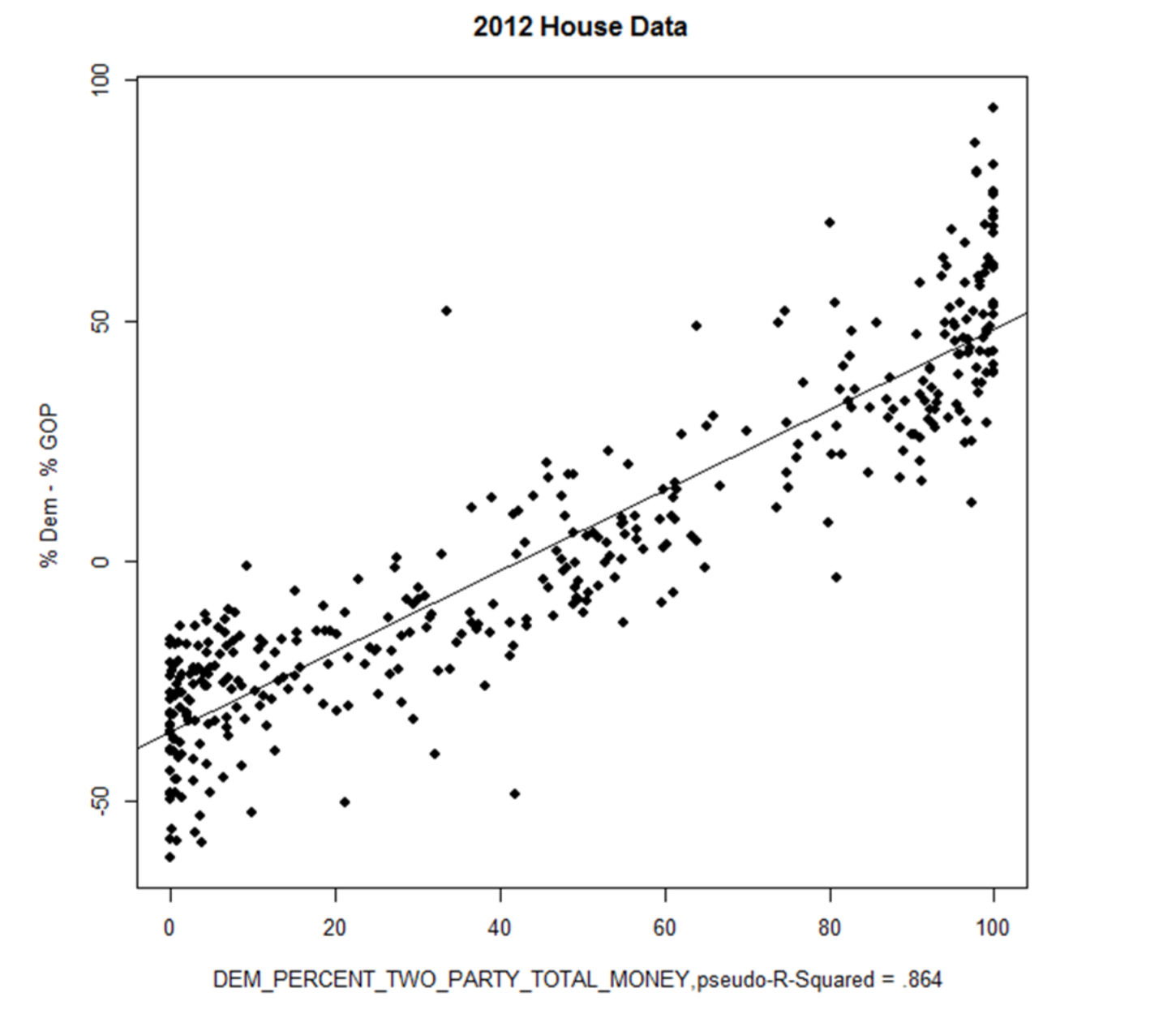

They show the strength of this relationship through a simple graph. The line going out to the right in the graph shows the Democratic percentage of the total money flowing into the race for the major parties and runs from 0 to 100 percent. The vertical line shows the percentage of the major party vote that the Democrats won. Dots represent individual House races in 2012.

As Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen sum up:

At the bottom left Democrats spend almost no money and get virtually no votes; at the top right, they spend nearly all the money and garner virtually all the ballots, calculated as proportions of totals for the major parties.

If money and voting outcomes were unrelated, then the dots representing individual House races in 2012 would be scattered all over the square. If they were perfectly related, the dots would all cluster tightly on a line.

Not only in 2012, but in every election for which the data exists (from 1980 to 2012), Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen found that the graphs came out with neat, straight lines, with minimal scattering of dots. The link is clear: when the Democrats spend more than Republicans, their candidates win. When Republicans spend more than Democrats, they win.

There was but one exception, the Senate races of 1982, when Senator William Proxmire, whose disdain for fundraising was legendary but who still won elections, brought down the average. Otherwise, with alarming regularity, Democrats and Republicans candidates’ share of the vote was correlated, to an astonishing degree, with the amount money spent in the campaign.

Nothing like this graph has ever made its way into a political science textbook. That it now exists sure should change what Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen call the “optics” of the campaign finance discussion. But will it?

Does Money Just Follow Popular Candidates?

Political scientists have long had way out of admitting the implications for democracy of such a direct a relationship between politics and money: the idea that the wealthy tend to spend on the most popular Congressional candidates. Their “influence,” the thinking goes, is thus nothing more than a reflection the will of the people. They don’t force any outcome other than the one that voters would choose. Political scientists call this idea “reciprocal causality.”

Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen tackle this issue head on. They use a cutting-edge method invented by Dutch statistician Peter Ebbes and recently studied by Irene Hueter in another new INET paper. The researchers find that while reciprocal causation happens, its extent is not large: money’s effect is direct and powerful.

They confirm their conclusion by using another method now widely employed in finance and economics: they look at published gambling odds on the chances of a Republican takeover of the House in 1994. These are relevant because a huge wave of money swept the Republicans to victory in that election, but the odds never moved very much. The relative lack of change rules out the idea that soaring expectations of victory drove the wave. But the wave, when it came, nevertheless produced a big change in the electoral outcome, just as a money-driven “investment theory” of political parties would predict.

Eccentric Gazillionaires or Big Corporations Driving Elections?

Their paper closes by examining the notion that right wing politics in America has been driven by donations piling up from eccentric entrepreneurs like investor and conservative mega-donor Foster Friess — the sort of people who are widely imagined to populate the Forbes 400 list of wealthiest Americans – rather than mainline big business corporations, such as those on the Fortune 500 list.

On the contrary, the researchers find that “a simple count of firms and investors on Forbes show that the largest American corporations support Tea Party Congressional candidates and organizations supporting the movement, such as Freedom Works, at much higher rates than Forbes 400 members. Even making due allowances for Dark Money, the difference is substantial.”

Evidently American big business firms are not centrist, as many pundits would have it. As Ferguson and his colleagues put it:

Stories that the steady rightward drift of the American political universe is somehow the work of exceptionally ideological individual entrepreneurs are huge over-simplifications. If the center is not holding in American society – and it rather plainly is not – America’s largest companies are as implicated as anyone else; indeed, perhaps more so.

This state of affairs explains why economic inequality has grown into a crisis, with social unrest amplified by economic distress. Because of this money-driven system — which has been getting worse since 1970s up to the current dysfunctional mess — when the rich don’t feel like paying taxes, we all suffer. Infrastructure collapses, schoolchildren and sick people suffer, and hard-working citizens are robbed of their fair share of the country’s prosperity and end their lives struggling keep body and soul together.

Ferguson, Jorgensen, and Chen conclude:

It goes without saying that this news is not reassuring; particularly in elections below the federal level – in states and local elections, we suspect, money has come to dominate outcomes to a frightening degree, not least because it is unlikely that the Republican advantage is offset there to the degree that it has been in recent federal elections. If it turns out that the U.S. has entered a Post-Democratic age, the situation will not be improved by social scientists behaving like ostriches. It is time economics, political science, and history recognize the reality of industrial and financial blocs within parties and acknowledge money’s powerful effects on elections.

If mainstream social scientists are not pursuing the truth, what exactly are they pursuing? Whatever it is, it does not appear to be good for democracy.

First of all thank you for giving us this very interesting link I have often wondered if we would not do better if we simply randomized elections. One could Set certain standards of education, or none, for that matter, and then randomized all citizens. When your number came up you went to Washingt for a few years. You would be paid but not offered a pension. It would simply be your Du as a citizen. After a number of years, perhaps four or six, you would return home to whatever you were doing before. You would be precluded from taking Jobs from Institutionen you made decisions on during your term. Exemptions could be issued for professions that require continuing practice like surgery. People forced into this sort of Federal Service would not be arrogant because it is just a Draw. They would have little incentive to Game the system. The quality of candidate would not be worse than what we have. I mean does anyone think the candidates we have are better than a random Draw? We would have done better this election throwing darts at a phone book.

Yes. Treat serving in office like jury duty. That way the elite wouldn’t know who to bribe, and it would get rid of narcissists running for office.

If mainstream social scientists are not pursuing the truth, what exactly are they pursuing?

The dollar. Principles be damned.

In ancient Greece, what you propose, also called surtition, is what democracies used. The ancient Greeks knew that elections produce oligarchies. Then and now, the rich will buy most elections.

One area where sortition could be very useful for strengthening public confidence in democracy would be in legislative reapportionment. When it comes time to reapportion after the census, choose a Reapportionment Commission by lot from the rolls of a state’s registered voters. Then draw up a list of, say, 50 possible reapportionment plans, all of which would have to observe some rules such as compact districts and equal populations. Then have the randomly-chosen commission pick the winning reapportionment plan by lot. Voila. Gerrymandering effectively outlawed.

Any chance of something like this being adopted anywhere?

birds sing, crickets chirp, grass grows, paint dries…

Why another Commission? Humans are what got us into this mess. Something as simple as reapportionment could be done by mature, open source mapping software given parameters of population counts and political boundaries.

In cyber I trust. Skynet, anyone?

By the above reasoning, voting machines should be giving us really honest elections. How’s that workin’ out for ya? Ask banking security expert Stephen Spponamore. His’s recommendation is to use paper ballots, counted in the open.

The fatal weakness in computerized decision-making systems is that they are intrinsically non-transparent to the vast majority of the public, and often unavailable for expert inspection, making it possible for miscreants to hide manipulations more easily than gangsters dumping bodies in the ocean. I’m all for using technology, but ONLY when there’s a clear advantage, and if the risks are minor and/or well controlled. By today’s standards, that makes me a Ludddite. But human decision-making is already difficult enough without adding a layer of hackable machine complexity into the mix.

KISS

Your comment makes no sense given my proposition. To quote Pauli, “This isn’t right. This isn’t even wrong.”

As ‘human’ indicated, the proposal is to use open source software. That rules out your “fatal weakness”.

Man, that’s a good idea. Besides big $, gerrymandering stifles democracy, quite blatantly.

It is a sad but true fact that modern ‘democratic institutions’ are promoted all over the world as a method by which the majority of citizens—who possess little or no wealth—are able to obtain a government that will defend/advance their interests—over and above the interests of the elites—simply because they have the numbers in their favor.

But the ‘ruling class’ of every country that adopts the ‘modern democracy’ model learns quickly that agreeing to submit to the will of the majority does not exactly put them in the position of hapless servants of the democratic mob.

As long as they are willing to spend some of their financial resources on the effort, they can obtain the same dominating control over the behavior of the government that a military dictatorship would give them, only in a more sophisticated manner.

When it was just the Republican Party that pushed this political philosophy, concentrating on the upper crust, it became quite apparent that they could regularly win elections by cultivating an identity for their party that would appeal to large numbers of middle class voters.

They do it by dividing the country, not by seeking to unite it. They want enough middle class voters to see the political landscape as Us vs. Them. They, of course, are The Good People, as evidenced by the material affluence that so many of them appear to enjoy.

The claim that they are Good is achieved by relentlessly criticizing Them for every imaginable flaw, by ridiculing them and mocking them without letup. For many wage earners of modest means who understand little about politics and history and government, the choice is simple: do I identify with the group that I’m always hearing ridiculed? Or do I identify with the group that is making fun of them?

The Oligarchy’s many willing minions understand that average voters can be manipulated in this way and that all it usually takes to win an election is having enough money to saturate the airwaves and the pixels with their criticisms of Them.

Now that institutional Democrats have embraced the same cynicism that has fed the Republican Party for decades, the future is looking particularly bleak…

Wow, great article and sobering to see the work behind what many of us have “sensed” (though that was placated by the thought that perhaps money simply followed the winner).

No doubt the correlation is huge and problematic, but the analysis would have to factor in the competitiveness of districts / gerrymandering to be truly enlightening. No doubt some of these dots reflect completely uncompetitive districts where minimal expenditures for the sure-to-win incumbent drive the correlation.

yeah, I’m wondering the same, e.g. Dem committee chair in relatively safe seat still gets big, corrupting bucks from corporations bidding for their vote. ?

The reward for serving in high public office should be lifetime retirement. If you choose to serve as a senator, representative, or president, after your term of office is over you should receive a lifetime retirement salary indexed to twice the national average. With one stipulation— you can never receive compensation from any corporation or individual for the rest of your life that increases your income.

Add to that a mandatory death penalty for receiving bribes— I’m thinking of you, Bill, Hillary & Chelsa with your family Crime Foundation– and we would have made a good start toward a more honest system.

Forbes magazine casually mentioned, well before Citizens United, that bigger donations meant more access and greater likelihood of getting one’s view considered and implemented. They provided a type of guidance to their readers on how to game the system. People could say that at least they were up front about that.

As an indication of how ethics and morals change, look at the magazine’s back quotes and sayings page. For decades, there was a saying printed at the top: With all thy getting, get understanding. That saying disappeared some years ago. Now, readers get, and don’t worry about the understanding.

Readers may be reminded of Martin Gilens’ work and his book “Affluence and Influence”. If you follow the link below, Prof. Gilens is featured in a short video. He seems genuine.

From the book link at Princeton U:

Link to book page at Princeton and video:

http://press.princeton.edu/titles/9836.html

The corporate media play a key role because the vast majority of USians get their news from the boob tube and form their opinions from ads placed in that (fake) reality show. Many addicted people have the device running during all their discretionary waking hours. I’d like to see a new movement: “Ditch your TV.”