Yves here. Major financial news outlets, such at the Telegraph yesterday (via Ambrose Evans-Pritchard) and the Financial Times today have reported on a new Bank of International Settlement paper that raises new alarm about China’s debt levels. One reason to take it seriously is that one of its authors, Claudio Borio, was with William White warning about the dangers of housing bubbles in many advanced economies in the runup to the crisis and was ignored.

Some experts have discounted this BIS warning because it raises concerns about China’s overall debt level, which is high by emerging economy standards but not terribly so by those of advanced economies. But its other alarm, about the rapid rise in debt, is harder to ignore since big jumps in borrowings tend to be the result of leveraged speculation and/or unproductive investment.

Steve Keen, one of the few economists to predict the financial crisis, also sees a big increase in debt at a national level from a moderate or high base level as a harbinger of at best future zombification. As he explains in a recent presentation, a mere halt in debt growth in that scenario will produce a crisis.

By Raúl Ilargi Meijer, editor at Automatic Earth. Originally published at Automatic Earth

Lots of China again today. Most of it based on warnings, coming from the BIS, about the country’s financial shenanigans. I’m getting the feeling we have gotten so used to huge and often unprecedented numbers, viewed against the backdrop of an economy that still seems to remain standing, that many don’t know what to make of this anymore.

Ambrose Evans-Pritchard ties the BIS report to Hyman Minsky’s work, which is kind of funny, because our good friend and Minsky adept Steve Keen is the economist who most emphasizes the need to differentiate between public and private debt, in particular because public debt is not a big risk whereas private debt certainly is.

And that happens to be the main topic where people seem to get confused about China. To quote Ambrose: “..Outstanding loans have reached $28 trillion, as much as the commercial banking systems of the US and Japan combined. The scale is enough to threaten a worldwide shock if China ever loses control. Corporate debt alone has reached 171pc of GDP..”

The big Kahuna question then becomes: should Chinese outstanding loans and corporate debt be seen as public debt or private debt, given that the dividing line between state and corporations is as opaque and shifting as it is? Even the BIS looks confused. I’ll address that below. First, here’s Ambrose:

BIS Flashes Red Alert For a Banking Crisis in China

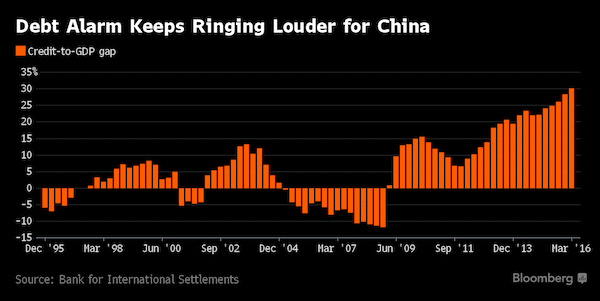

The Bank for International Settlements warned in its quarterly report that China’s “credit to GDP gap” has reached 30.1%, the highest to date and in a different league altogether from any other major country tracked by the institution. It is also significantly higher than the scores in East Asia’s speculative boom on 1997 or in the US subprime bubble before the Lehman crisis.

Studies of earlier banking crises around the world over the last sixty years suggest that any score above ten requires careful monitoring. The credit to GDP gap measures deviations from normal patterns within any one country and therefore strips out cultural differences. It is based on work the US economist Hyman Minsky and has proved to be the best single gauge of banking risk, although the final denouement can often take longer than assumed.

[..] Outstanding loans have reached $28 trillion, as much as the commercial banking systems of the US and Japan combined. The scale is enough to threaten a worldwide shock if China ever loses control. Corporate debt alone has reached 171pc of GDP, and it is this that is keeping global regulators awake at night. The BIS said there are ample reasons to worry about the health of world’s financial system. Zero interest rates and bond purchases by central banks have left markets acutely sensitive to the slightest shift in monetary policy, or even a hint of a shift.

Bloomberg commented on the same BIS report:

BIS Warning Indicator for China Banking Stress Climbs to Record

[..] the state’s control of the financial system and limited levels of overseas debt may mitigate against the risk of a banking crisis. In a financial stability report published in June, China’s central bank said lenders would be able to maintain relatively high capital levels even if hit by severe shocks.

While the BIS says that credit-to-GDP gaps exceeded 10% in the three years preceding the majority of financial crises, China has remained above that threshold for most of the period since mid-2009, with no crisis so far. In the first quarter, China’s gap exceeded the levels of 41 other nations and the euro area. In the U.S., readings exceeded 10% in the lead up to the global financial crisis.

Why am I getting the feeling that the BIS thinks perhaps just this one time ‘things will be different’? If the credit-to-GDP gap (difference with long-term trend) anywhere exceeded 10%, that was a harbinger of the majority of financial crisis. But in China to date, with a 30.1% print, ‘the state’s control of the financial system and limited levels of overseas debt may mitigate against the risk of a banking crisis’. That sounds like someone’s afraid to state the obvious out loud.

If you ask me there’s a loud and clear writing on the Great Wall. But regardless, I didn’t set out to comment on the BIS, I just used that to introduce something else. That is to say, early today, CNBC ran an article on the Chinese property market, seen through the eyes of Donna Kwok, senior China economist at UBS.

Donna sees some light in fast rising home prices (an ‘improvement’..) but also acknowledges they constitute a challenge. She mentions bubbles – she even sees ‘uneven bubbles’, a lovely term, and ‘selective pockets of bubbles’-, but she does seem to understand what’s going on, even if she doesn’t put it in the stark terminology that seems to fit the issue.

CNBC names the article “China Faces Policy Dilemma As Home Prices Jump In GDP Boost,” an ambiguous enough way of putting things. A second title that pops up but has apparently been rejected by the editor is: “Chinese Property Market Is Improving: UBS”. That would indeed have been a bit much. Because calling a bubble an improvement is like tempting the gods, or worse.

I adapted the title to better fit the contents:

China Relies on Housing Bubble to Keep GDP Numbers Elevated (CNBC)

Policymakers in China were facing the dilemma of driving growth while preventing the property market from overheating, an economist said Monday as prices in the world’s second largest economy jumped in August. Average new home prices in China’s 70 major cities rose 9.2% in August from a year earlier, accelerating from a 7.9% increase in July, an official survey from the National Bureau of Statistics showed Monday. Home prices rose 1.5% from July. But according to Donna Kwok, senior China economist at UBS, the importance of the property sector to China’s overall economic health, posed a challenge.

It contributes up to one-third of GDP as its effects filter through to related businesses such as heavy industries and raw materials. “On the one hand, they need to temper the signs of froth that we are seeing in the higher-tier cities. On the other hand, they are still having to rely on the (market’s) contribution to headline GDP growth that property investment as the whole—which is still reliant on the lower-tier city recovery—generates…so that 6.5 to 7% annual growth target is still met for this year,” Kwok told CNBC’s “Street Signs.”

The data showed prices in the first-tier cities of Shanghai and Beijing prices rose 31.2% and 23.5%, respectively. Home prices in the second tier cities of Xiamen and Hefei saw the larges price gains, rising 43.8% and 40.3% respectively, from a year ago. Earlier, the Chinese government introduced measures aimed at boosting home sales to reduce large inventories in an effort to limit an economic slowdown. While the moves have boosted prices in top-tier cities with some spillover in lower-tier cities, there were still concerns of uneven bubbles in the market.

“We are seeing potential signs of selective pockets of bubbles appearing again, especially in tier 1 and tier 2 cities,” Kwok said. The Chinese government in the meantime was rolling out selective cooling measures in these cities to try to even out growth. “If it’s navigated in a such a way that the (positive) spillover to the adjacent tier 3 cities continues to spread further, then maybe that’s where you may get a first or second best outcome resulting,” she added.

To summarize: China can only achieve its 6.5 to 7% annual GDP growth target if the housing bubble(s) persist, and that’s the one thing bubbles never do.

If housing makes up -directly and indirectly, after ‘filtering through’- one third of Chinese GDP, which is officially still growing at more than 6.5%, then the effects of a housing crash in the Middle Kingdom should become obvious. That is, if the property market merely comes to not even a crash but just a standstill, GDP growth will be close to 4%. And that is before we calculate how that in turn will also ‘filter through’, a process that would undoubtedly shave off another percentage point of GDP growth.

So then we’re at 3% growth, and that’s optimistic, that would require just a limited ‘filtering through’. If the Chinese housing sector shrinks or even collapses, and given that there is a huge property bubble -intentionally- being built on top of the latest -recent- bubble, shrinkage is the least that should be expected, then China GDP growth will fall below that 3%.

And arguably down the line even in a best case scenario both GDP growth and GDP -the economy itself-, will flatline if not fall outright. Since China’s entire economic model has been built to depend on growth, negative growth will hammer its economy so hard that the Communist Party will face protests from a billion different corners as its citizens will see their assets crumble in value.

What at some point will discourage Beijing from keeping on keeping blowing more bubbles to replace the ones that deflate, as it has done for years now, is that China desperately seeks for the renminbi/yuan to be a reserve currency, it’s aiming to be included in ‘the’ IMF basket as soon as October 1 this year.

That is not a realistic prospect if and when the currency continues to be used to prop up the economy, housing, unprofitable industries etc. Neither the IMF nor the other reserve currencies in the basket can allow for the addition of the yuan if its actual value is put at risk by trying to deflect the most basic dynamics of markets, not to that extent. And not at that price either.

The Celestial Empire will be forced to choose, but it’s not clear if it either acknowledges, or is willing to make, such a choice. Still, it won’t be able to absorb all private debt and make it public, and still play in the big leagues, even if other major countries and central banks play fast and loose with the system too.

They have to doing it in manufacturing as well and not just domestic related to contruction but export. They export us 70 billion in clothes and textiles to us alone. That along with smart phones is about half their sports to us…an eeveryone. Both are very labor intensive and based on Chinese factory wages they should be unviable on both. The Imf wondered how they kept it up …..well I think you just explained

I’ve been following the Chinese economy with interest since my first visit there in the late 1990’s, and even then there was clear evidence of malinvestment (huge hotels and airports in tiny impoverished regional cities) and localised bubbles. I was convinced that the reckoning would come after the Beijing Olympics (I thought that was the perfect time for the CCP to start much needed reforms), but it didn’t happen. I’ve noticed that Chinese bulls have this year almost given up on predictions – the seeming ability of the CCP to keep inflating at will has turned the bulls into ‘wait and see’ watchers. But of course the longer a correction is put off, the worst the reckoning is likely to be. The weirdness of the current bubble (not just in property, there have also been huge rises in the stock market) which seems divorced from any economic logic might just be a sign that this is finally the end game. But I’ve thought that before and I’ve been wrong.

The particularly worrying thing is that it does seem that the Li and Xi regime has run out of reform ideas. I did think that with a firm grip on the tiller and a willingness to make tough reforms the necessary correction would be manageable. It would be less a bust, and more a difficult, but not catastrophic period of low growth and deflation. I’m beginning to think this is much less likely and a full on financial collapse is now a bit more likely.

There are wider consequences as well. I think a rising bubble will encourage Chinese insiders to give it one last stroke, and then cash out, which inevitably means more Chinese cash rushing into Australian, US and UK property (maybe more the latter, as its seen as good value due to low sterling). This will give those bubbles one last inflation before they start bursting. I suspect Brexit will make the UK one go first, and probably, finally, after many decades, the Aussie one will go. It won’t be pretty.

Incidentally, Michael Pettis has an excellent post on why reforming the Chinese banking system is not enough – the debt is not just bank debt. He also sets out clearly the basic options available (he clarifies some of those in the discussion below). Interestingly, he includes the option of very high taxes on the rich. Given Chinese history, the rich are likely very much aware of this option which is why I think we’ll see a very rapid capital exodus once the merde hits the fan.

if I were trying to establish a new reserve currency, I would roll up private and public debt to create one of the prerequisites of a reserve currency, which is a large and liquid “risk-free” asset class. With the prevailing negative real interest rates, now is a good time to do it. The BIS paper seems like a political attack to derail China’s attempt to become a financial superpower.

I agree.

Thought experiment: What if China’s perpetual growth is proof that Modern Monetary Theory works? In that case, Wall Street & Friends would have an obvious interest in slandering or talking down China’s achievements.

China may be the poster child of reckless credit creation. But it’s a global phenomenon, as this chart shows:

Central bank assets have doubled from less than 20% to nearly 40% of GDP in the past decade, keeping bubbles of all kinds afloat.

If only this were a sustainable policy … :-(

Thanks, Jim. Bubble, yes, but a bubble built on what I understand are Keynesian prescriptions. The government sees a slowing economy and pumps money into the system to keep the growth, growth necessary to prevent a crisis for the entire global economy, going. Is China investing in infrastructure? Absolutely.

http://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2016-06-15/china-spends-more-on-infrastructure-than-the-u-s-and-europe-combined

Western countries and corporations meanwhile build huge mounds of debt on stock buybacks and warmongering, money which in large part already ends up in the pockets of executives and their political courtiers.

When and if a major crisis comes, I want the masses to be sure which donkey they need to pin the tail on.

Keynes lived in the gold standard and quasi-gold standard (Bretton Woods) era. He might have prescribed countercyclical fiscal spending. But most countries aren’t doing much of it.

Today’s runaway expansion of central bank balance sheets likely would have shocked Maynard Keynes. Wish he were around to write “The Economic Consequences of QE.”

One-word synopsis: BAD.

Yup. The crystal ball provided courtesy of Karl Marx shows a very bad future indeed.

China has a home court advantage the West doesn’t have: they’re (nominal) communists.

This means when the going gets tough they can easily nationalize things, as they are already doing with debt-for-equity swaps for over-indebted SOEs. Contrast the West, where instead of nationalizing Citi in 2009 for $4B (buying 100% of the common) we gifted them $174 B and supplied them with $2.5T in loan guarantees, and yet by all accounts the corpse is just as dead now as in 2009. Bank as Weekend at Bernie’s, no matter how many props you use dead is still dead, and what’s the point in letting the corpse fester, just put that sucker in the ground and get on with things.

It looks like there’s an open italics tag that needs closing.

If you tilt your head it should straighten right up.

I don’t pretend to understand the BIS quarterly report and only looked closely at the section linked to yesterday “Dissonant Markets”. Ignoring China for the moment — I got a strong feeling from the “Dissonant Markets” discussions that none of our economies are quite working the way they’re supposed to in theory. I also have a very hard time grasping the operations of an economy from a sea of financial measures. I like to think economies consist of more than the aggregate activities of stocks, bonds and currencies. The cross-couplings and shear complexity of the economic system as portrayed in the BIS quarterly report leaves me wondering whether anyone really knows what they’re doing and worse it leaves an uncomfortable feeling in my stomach that this time things really are different. I fear the next collapse promises to be on a different scale.

When asking what China will do with home prices it is first worthwhile to ask yourself:

House prices in the cities, even the “second tier” ones were already high and home sales have been so hot that they are moving faster than population growth. At that point you have a bubble but one that is not being driven by lots of people owning a new home, too big of a home, or even two homes. It is some well-connected people buying a lot of them or just driving the prices up beyond the reach of normals. In China there is no daylight between well-connected rich and the party members.

So asking that. What are the odds they will take any painful steps required to make the bubble burst?

Minor observation, but as Ilargi alluded in his last sentence, perhaps we are looking into a mirror in a Hall of Mirrors similar to that depicted in the climax to the film “The Lady from Shanghai”. The New York Fed pumped $19.5 billion into SOMA last week (Bless you, George Orwell). As Raymond F. Devoe said in the wayback machine: so long as the money is coming in, everything is fine.

Of course, private sector credit growth and the theme music are important to livin’ large, too … at least until the next Minsky moment.

Sounds like their economy turned western faster than anyone could expect, because reinflating housing bubbles is what has kept the west going since the 80s.

If they build it, they will come. Except no one comes and they tear it down and start all over again. Plenty of examples in Shenzhen, Shanghai, etc.